Charles Street is a typical Mayfair street. A varied range of architecture, a hotel, private houses, investment and wealth management companies, corporate offices, embassies, and much more hidden behind the facades of tall buildings that line the street.

I recently went for a walk along the street to find two pubs, the Footman and the Red Lion.

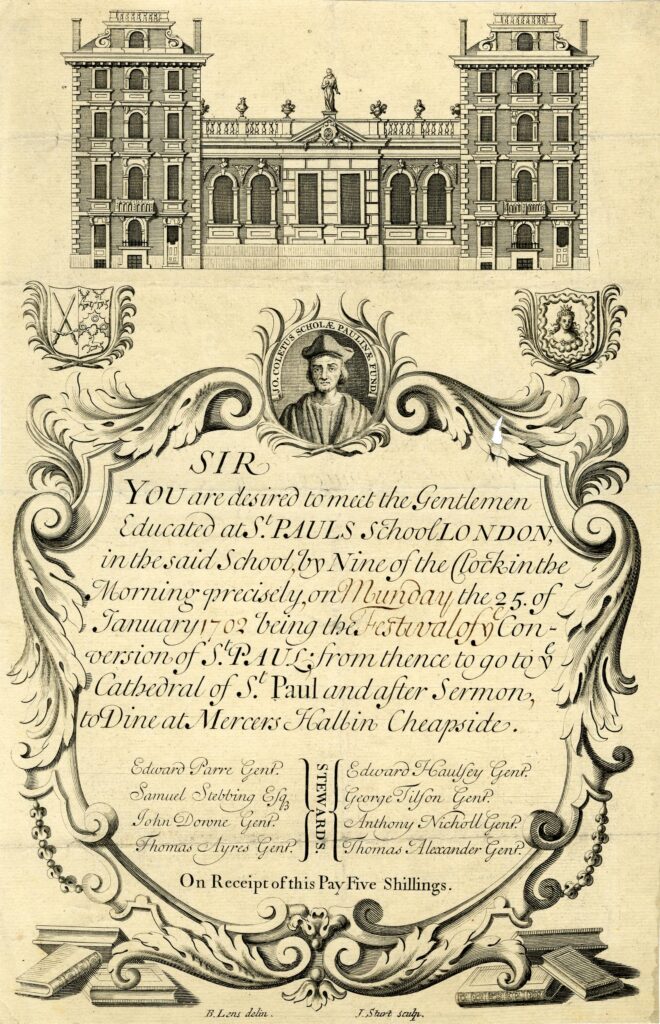

A photo of the Footman appeared in the 1920s three volume set of Wonderful London, when it was known as the Running Footman:

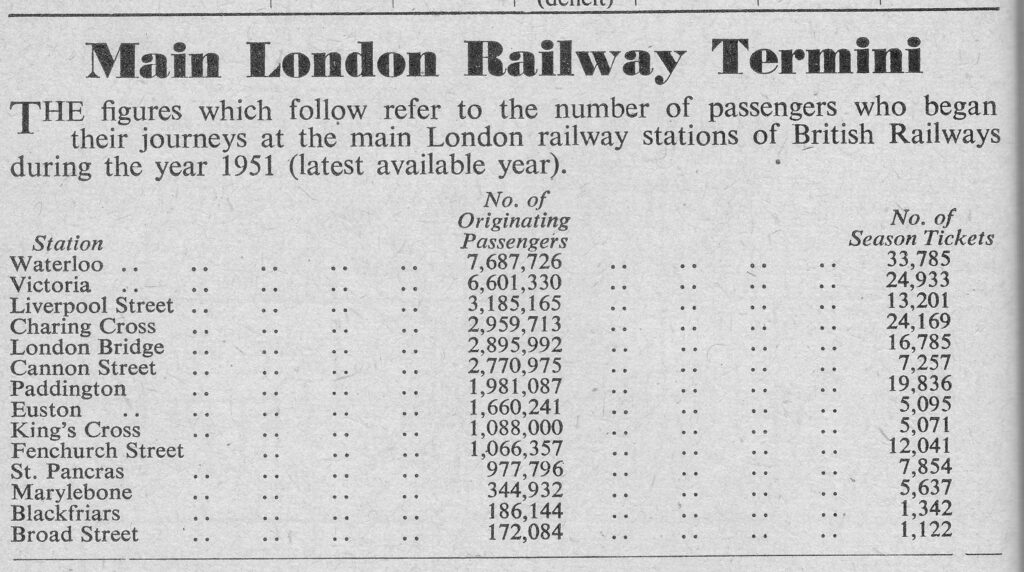

The following text is the commentary to the above photo in Wonderful London:

“THE RUNNING FOOTMAN, A PICTURE OF THE OLD MAYFAIR – Charles Street, off Berkeley Square, retains a pub named after that special kind of servant whose duty it was to run before the crawling family coach, help it out of ruts, warn toll-keepers, and clear the way generally. He wore a livery and usually carried a cane. The last person to employ a Running Footman is said to have been ‘Old Q.’ the Duke of Queensbery who died in 1810. The faded sign is fixed to the bay in the side street and appears here, over the taxi. The tavern is a bit of London from the days of ‘the Quality’, whose servants it served.”

Wonderful London has a rather rose tinted view of the role of a running footman. I suspect in reality it was really difficult and exhausting to keep ahead of a coach, and carry out any other manual activities such as lifting the coach out of outs.

I found an alternative description of the role of a running footman, which is probably more realistic:

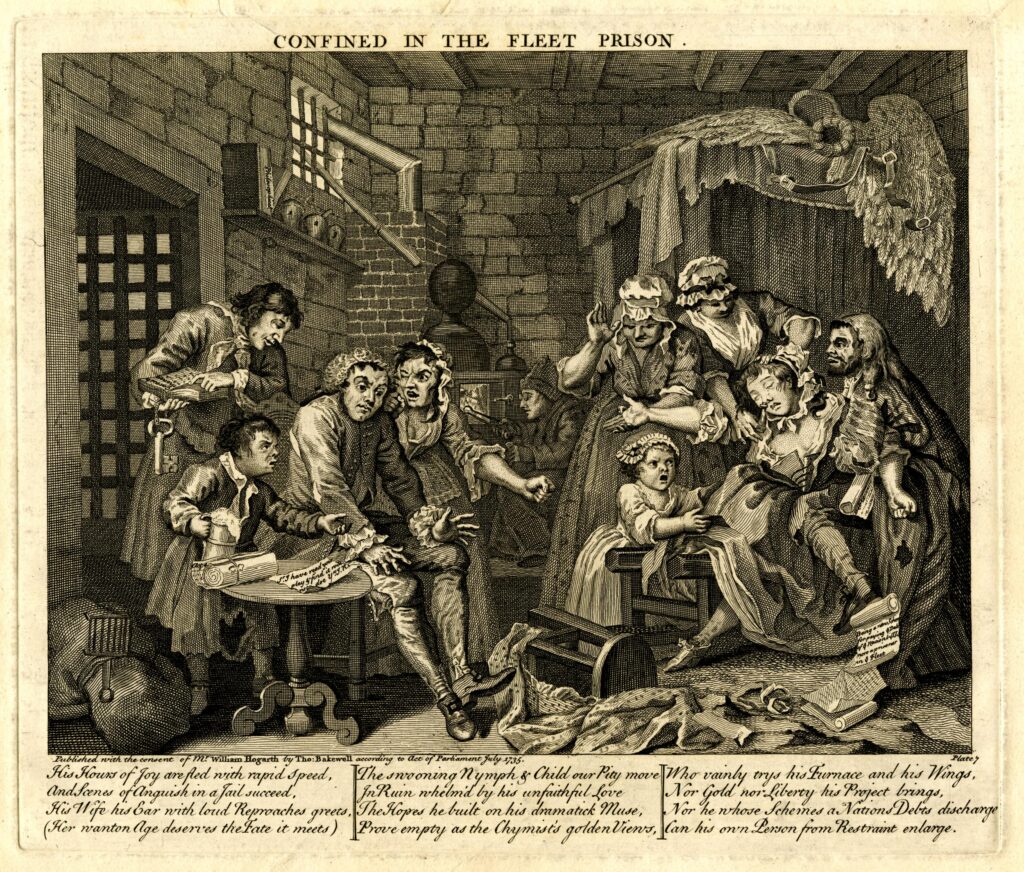

“The Running Footman – men have adopted various inhuman methods to increase their self-importance at different epochs, but few more inhuman than that of the running footman, of whom Mr. John Owen writes in his new novel, published today under the title of ‘The Running Footman’.

This 18th century barbarism, whereby a man was forced to run 30 yards in front of his master’s coach for incredible distances, naturally resulted in the runners death from heart disease or consumption.”

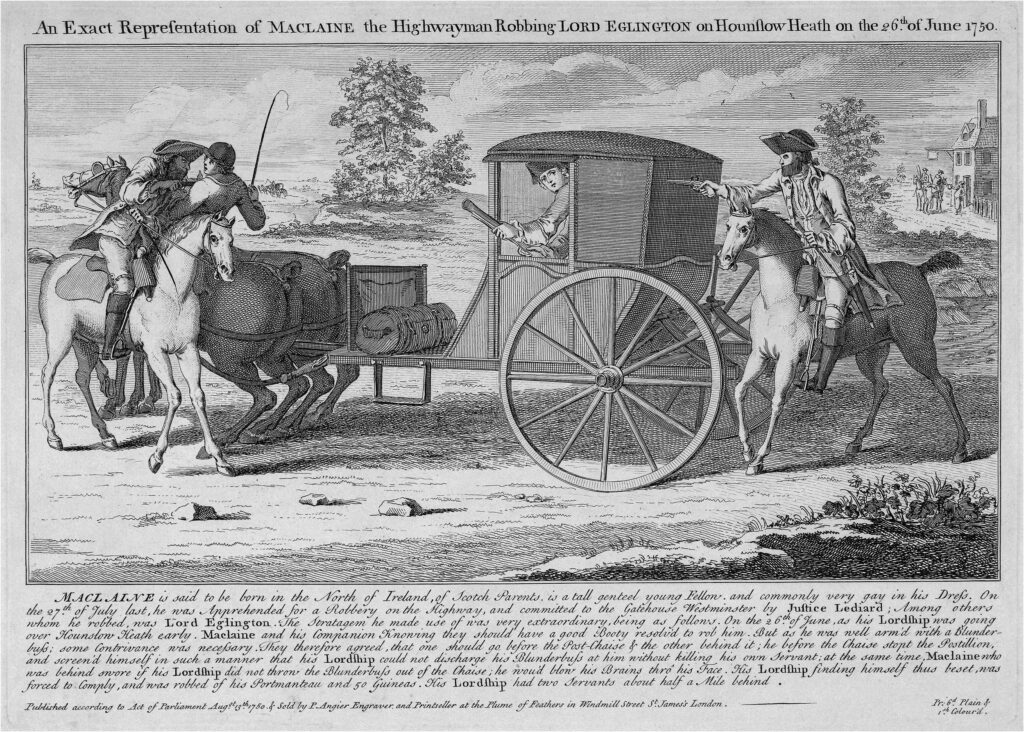

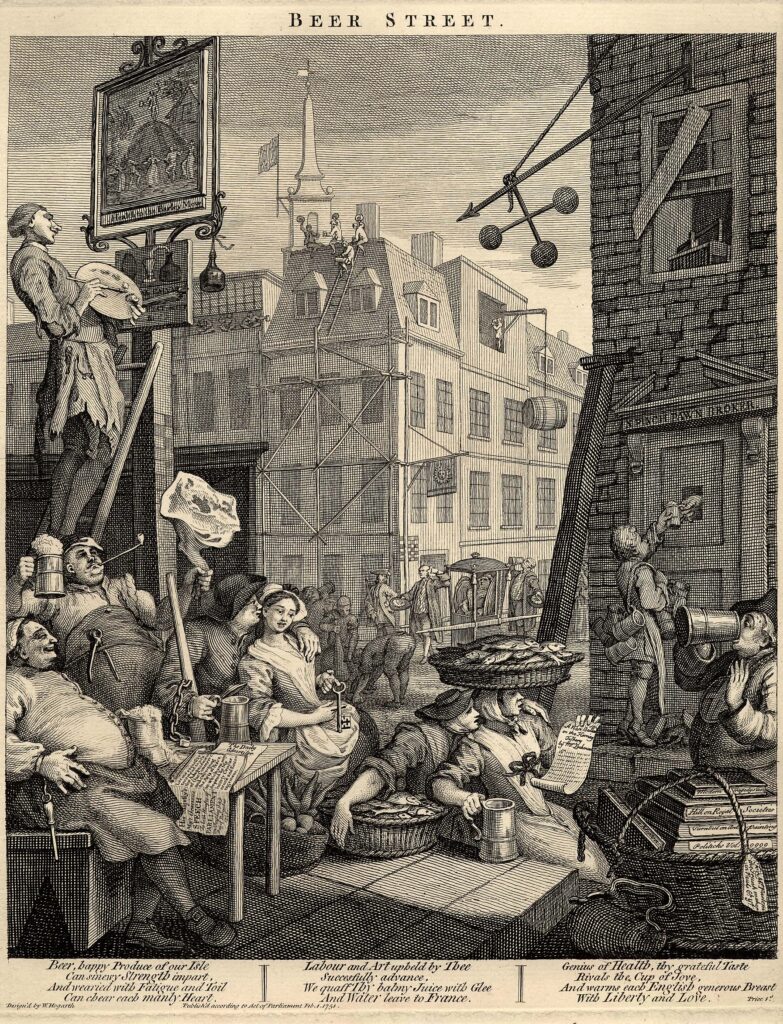

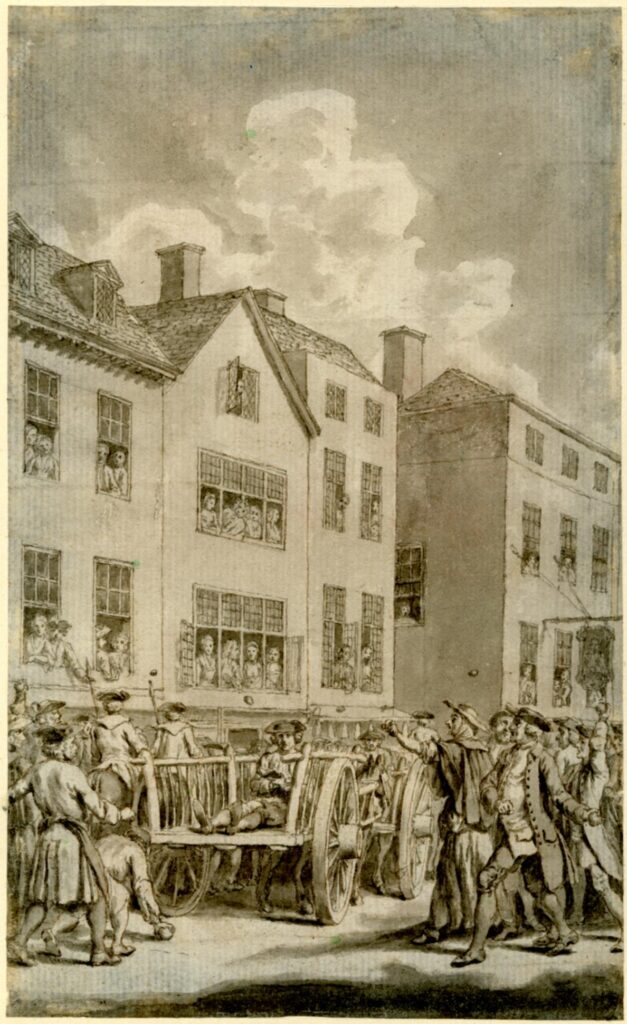

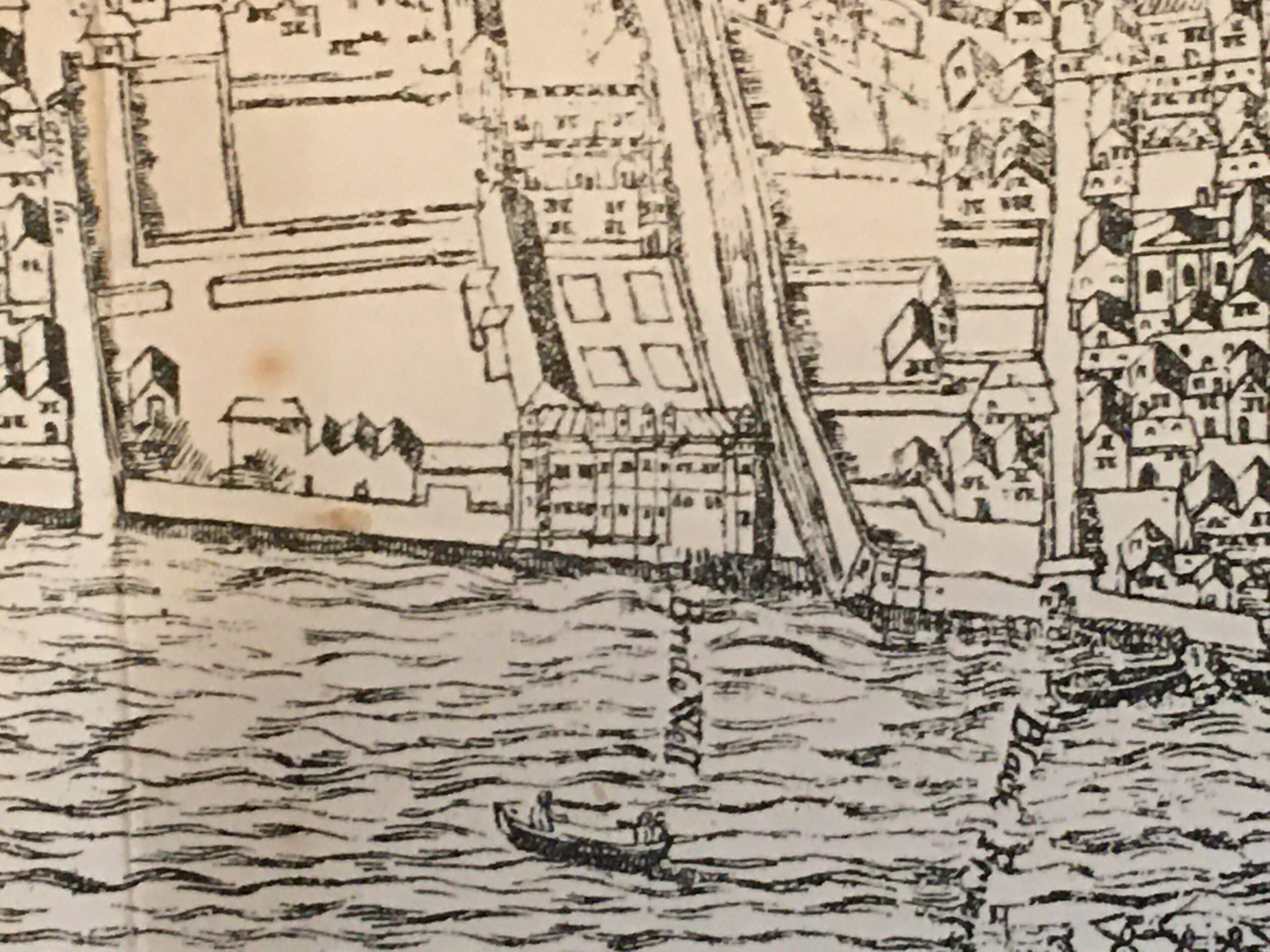

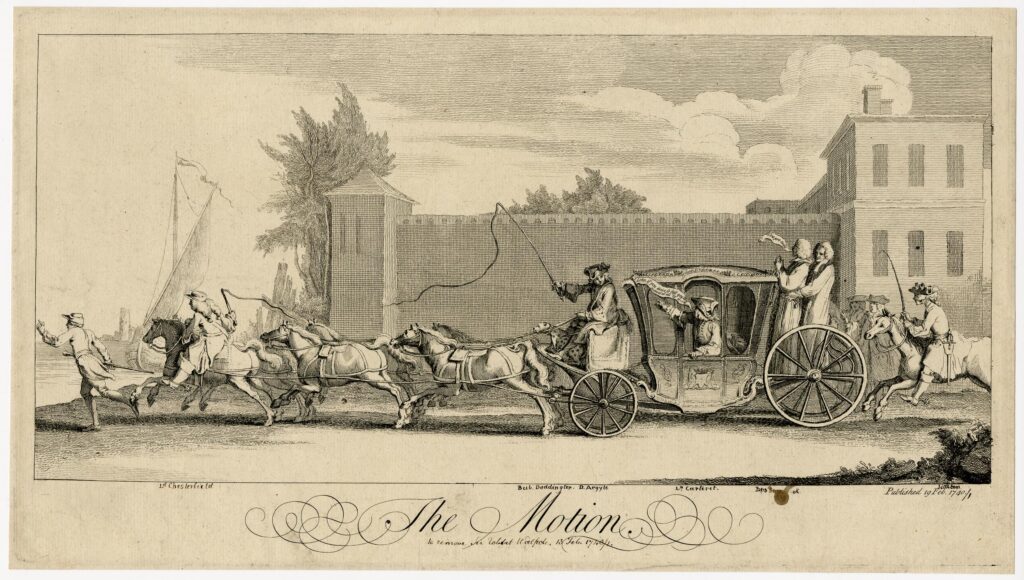

The following print from 1741 is a satirical interpretation of the opposition methods in the parliamentary motion to remove Robert Walpole from office, and shows a Running Footman at the left of the print, running in front of a team of horses and the coach.

As described in Wonderful London, he is carrying a cane ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

There was an interesting story of a Running Footman in the newspapers on the 5th of October, 1728, which hints at how fast they could run:

“A Foot Race of two Miles being Advertised to be Run last Thursday on the Marshes near Hackney River by young Women for a Holland Shift, as three were dressing in order to start, one of them was discovered to be a Running Footman to a Person of Quality, who seeing he was betrayed found means to re-mount the Horse he rode on with a Side-Saddle. The Mob understanding the matter pursued him in order to duck him in the River, but to make more speed, he dismounted, rid himself of his Petticoats, took to his Heels and got clear of them, after much more Diversion than the Race, which was afterwards run by the other two.”

The pub that is shown in the Wonderful London photo would only last for around another 10 years, as in the 1930s, the Running Footman would be rebuilt in the red brick style of pubs of the time, and it is this version of the pub that we find in Charles Street today, with the name truncated to just The Footman:

The shorter name is relatively recent as the pub also had the names “The Only Running Footman” and “I am the Only Running Footman”.

The original pub dates from the mid-18th century, and there are online references to the pub originally being called the Running Horse, although I cannot find any references from the late 18th century of a pub in Charles Street with this name.

The first newspaper references to the Running Footman date from the first decades of the 19th century, for example in May 1821 there were stables for sale in Charles Street, and the Running Footman was given as one of the places were details of the sale could be found.

The 1930s rebuild features an interesting extension to the roof, and the building is now taller than the rest of the terrace of which it was part:

The above photo shows the eastern end of Charles Street, with the southern end of Berkeley Square to the right.

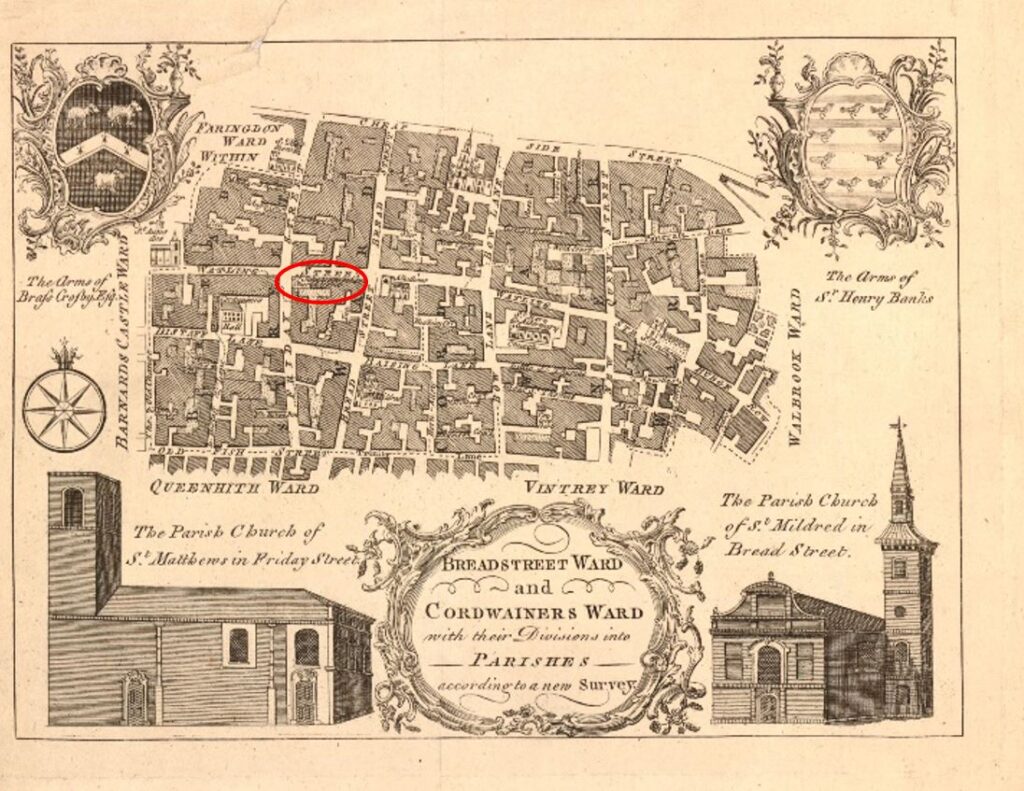

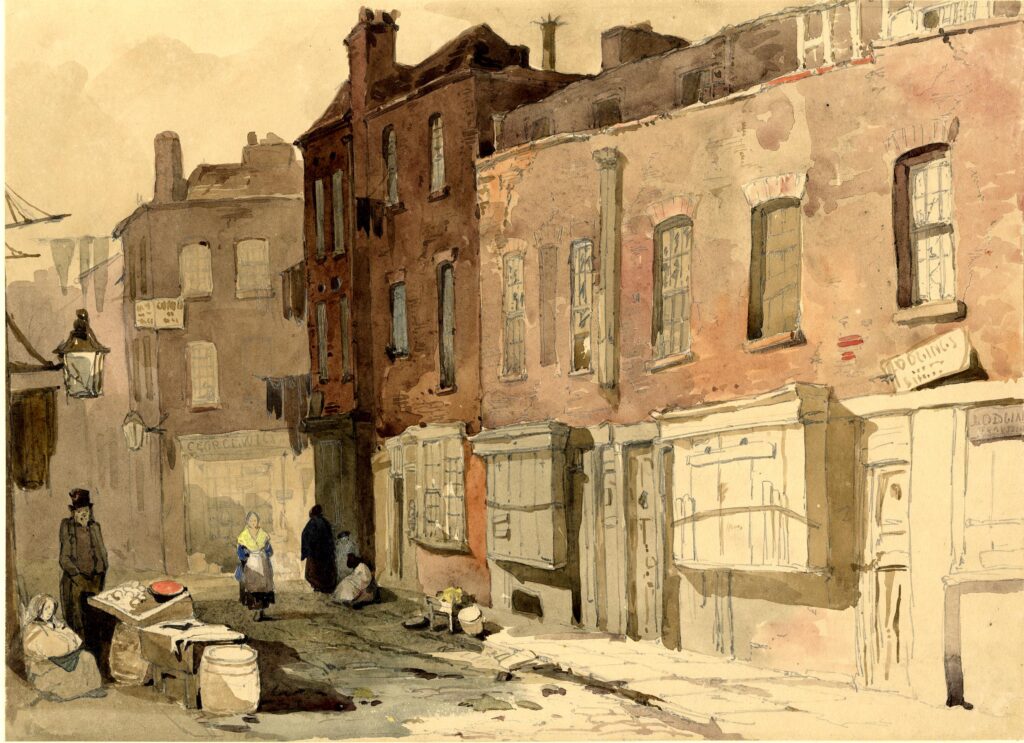

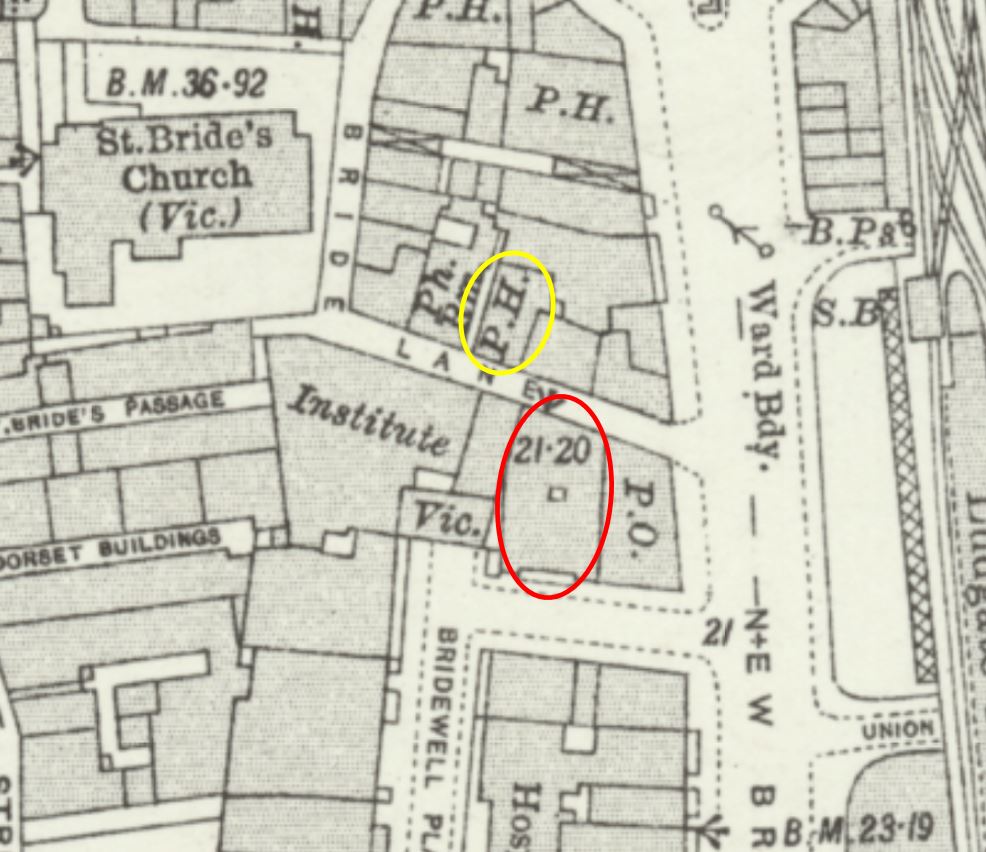

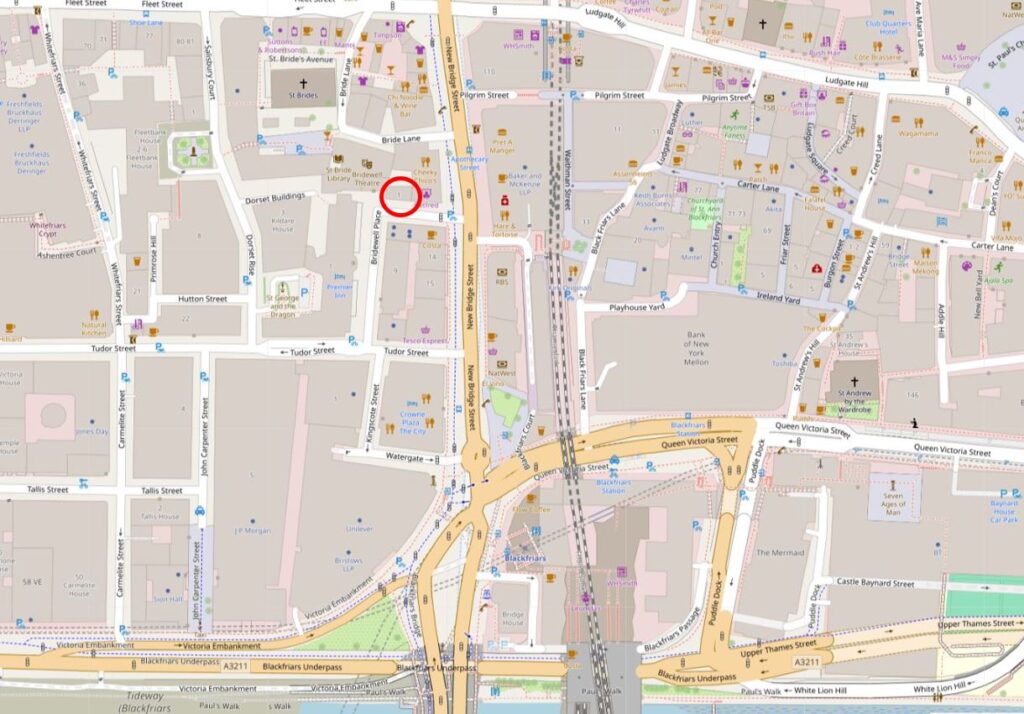

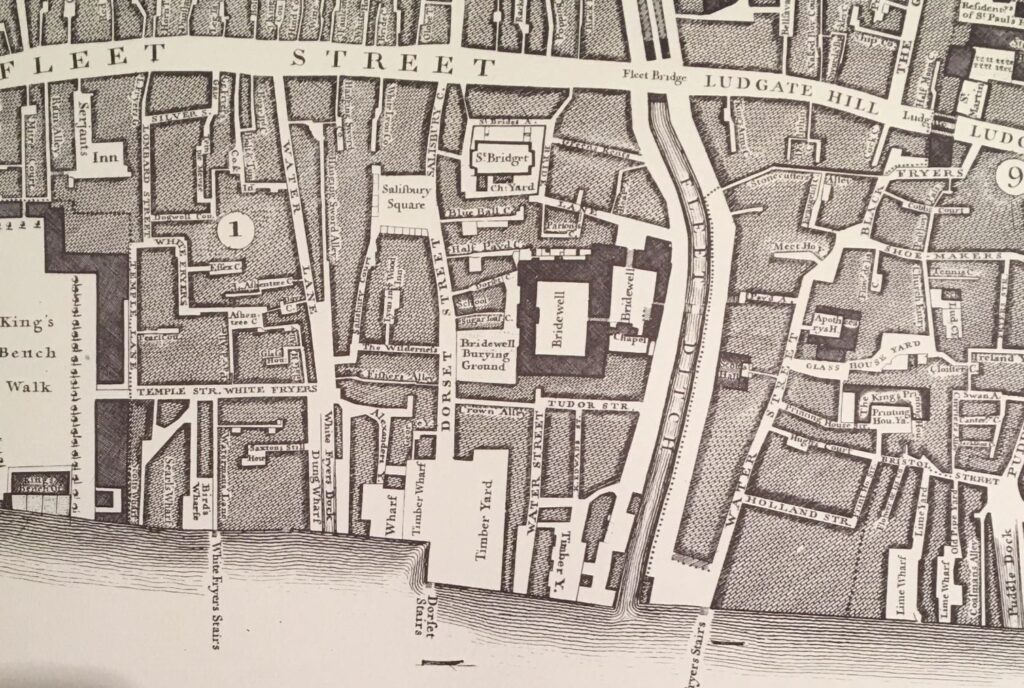

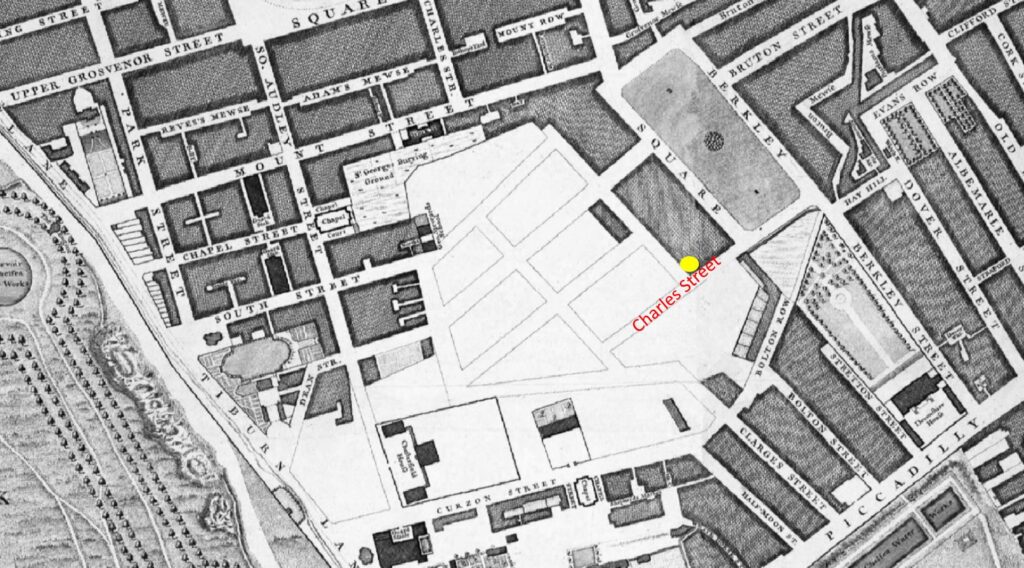

Charles Street seems to have been laid out during the later part of the 17th century. Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the surrounding built area, the upper eastern part of Charles Street has been built, and a blank space with street outlines covering the area west and north of Charles Street. The yellow circle marks the location of the Running Footman:

Although the map shows street outlines, the layout today is slightly different, and Charles Street extends to the corner of the space occupied by the large house at left, where it turns north. It was here I was heading next to find another pub, and to look at the mix of architecture along the street.

The original build of Charles Street was mid to late 18th century / early 19th century, brick terrace houses, and over the following decades many of these would be combined and rebuilt to leave the mix of architectural styles and periods that we see today:

At the junction with Queen Street, there is an open space with a tree in the centre, with the street turning slightly to the north. This point was the original end of Charles Street as shown in Rocque’s 1746 map, so the street may have originally terminated here, before being extended on as development of the area completed.

And as we walk along Charles Street, we continue to see the mix of architecture, including where original terrace houses have been combined and a new stone façade has been built over the original brick:

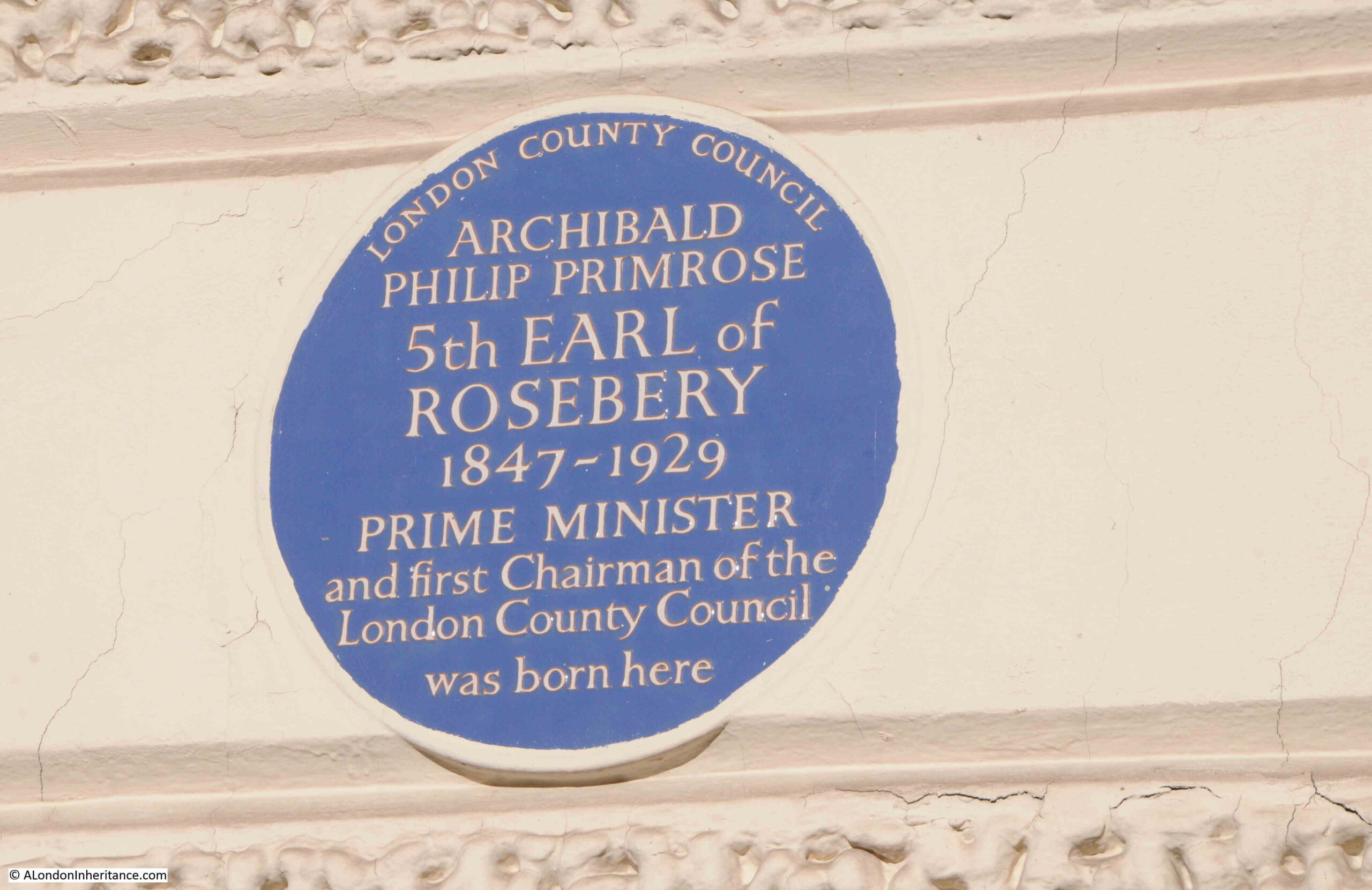

On the house shown above, there is a London County Council plaque stating that Archibald Philip Primrose, the 5th Earl of Rosebery was born in the house in 1847:

He was Prime Minister in the years 1894 and 1895, and he was also Chairman of the London County Council in 1889 and 1890, then again in 1892, and Rosebery Avenue in Clerkenwell is named after him. Rosebery Avenue was one of the late 19th century major roads built across London to ease the growing congestion of the time, and that swept away many old street, courts and alleys.

Towards the western end of Charles Street, the street suddenly narrows as it turns to run along the northern edge of large, terrace houses. This change in the street marks the point where the original gardens of Chesterfield House (see the extract from Rocque’s map earlier in the post) extended, with the street turning along the north east corner of the old gardens:

At the end of the narrow section of Charles Street, where there is a sharp bend up towards Waverton Street we can see what remains of the Red Lion, the second pub I was looking for in Charles Street (the scaffolding is on the building opposite, not on the old pub):

The Red Lion is now a residential property, having closed as a pub in 2009.

The building still retains some of the features of a London pub on the facade facing the street, however the rest of the building is very different.

After closing as a pub, it underwent a very significant rebuild, both above and below ground to create a very different space behind the façade.

I would not normally put a link to the Mail Online in the blog, however this is where I found an article on the conversion of the building from pub to residential, which includes a number of photos of the interior of the building, which are hard to reconcile with the view when you stand outside, and shows what can be done if you have £25 million to spare (in 2009).

A look down Red Lion Yard at the side of the old pub shows the way that the building has been extended above ground, in addition to the two levels below ground which doubled the overall space:

The article described the pub as a “dingy drinking establishment“. It did seem to have been left to run down over the last few years of being a pub, but in the few times I went in, it always seemed to be reasonably busy.

Unlike the Running Footman, the Red Lion was in a rather hidden part of the local streets, and it was a “local” pub so perhaps trade was not enough to keep the pub viable.

I suspect that when the company that owned the pub was offered a good sum of money, it was worth selling for development rather than retaining as a pub.

At the end of the alley leading into Red Lion Yard is this square of buildings, which again shows a level of redevelopment:

Entrance to Red Lion Yard alongside the old Red Lion:

Although the Red Lion is at the end of Charles Street, it is also in the southern edge of Waverton Street, with a short section leading up to Hill Street before continuing northwards. A short distance from the Red Lion in Waverton Street, significant development continues:

Looking back from in front of the Red Lion, along Charles Street. Again this narrow section of the street once had the gardens of Chesterfield House on the right:

Walking back along Charles Street, and this is Dartmouth House:

Dartmouth House is another building which started off as part of a brick terrace of houses, but after combining individual houses, extending the resulting building and constructing a new stone façade, we get the building we see today.

the first recorded resident was the Dowager Duchess of Chandos in 1757, and for the following centuries the house has been occupied mainly by a succession of Dukes, Earls, a Dowager and a Marquis – or “The Quality” as Wonderful London and other early references to the role of a Running Footman would have referred to them.

Since 1926, Dartmouth House has been the headquarters of the English Speaking Union (ESU).

The ESU have published a brief history of the house, and within this they reference the River Tyburn and that the brook runs under Dartmouth House and caused serious damage to papers stored in the basement in the 1990s.

According to “The Lost Rivers of London” by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers the Tyburn runs slightly to the east and south. Under the south eastern corner of Berkeley Square towards Curzon Street, rather than running under Dartmouth House, however the basement of Dartmouth House is within what would have been the marshy area surrounding the Tyburn and any remaining springs, a high water table after heavy rains etc. could still result in basement flooding.

Just one of the ways in which the pre-built environment, when the area was all fields streams and ponds, occasionally still bursts through to the 21st century.

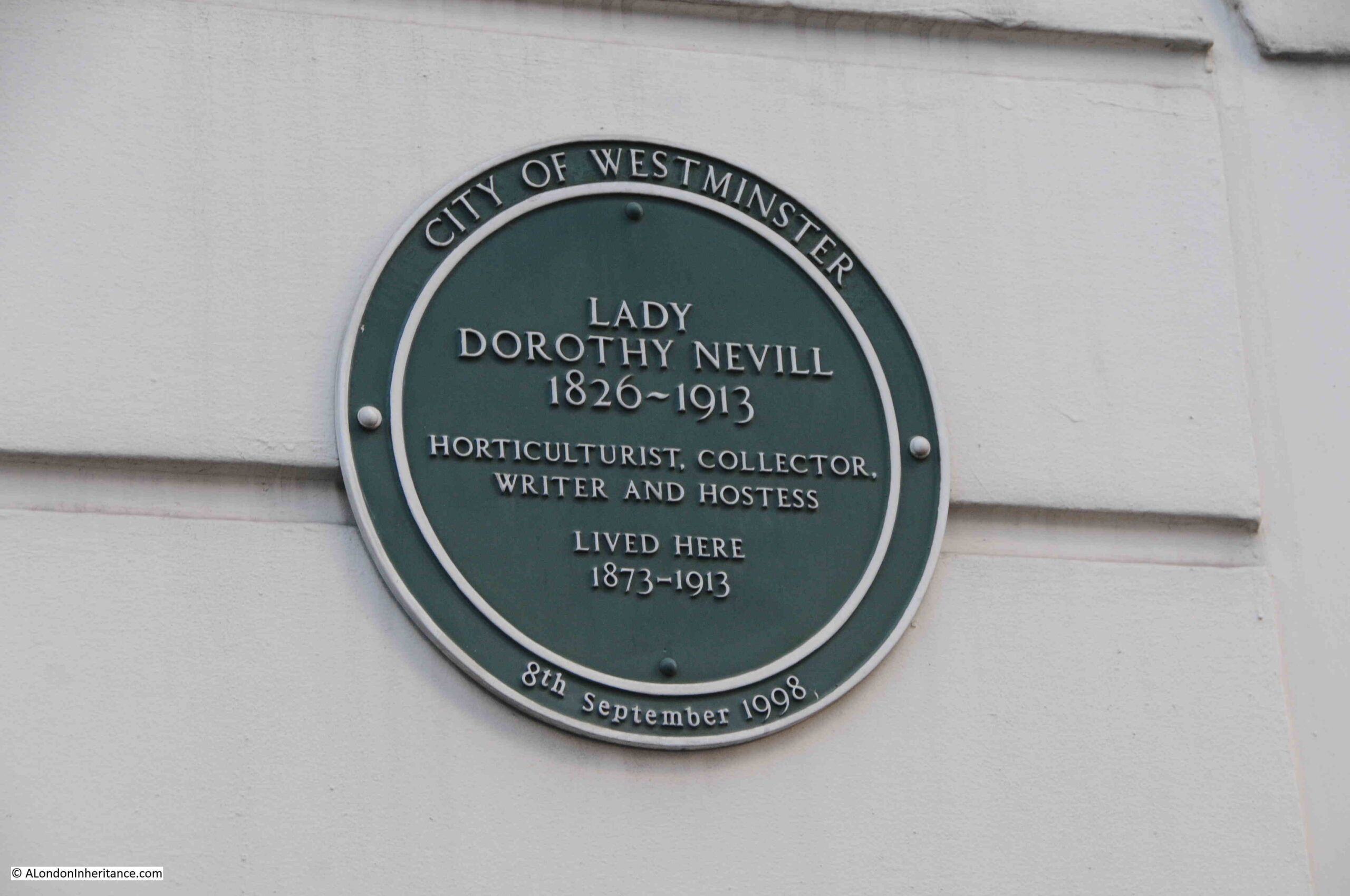

A house with a green City of Westminster plaque on the ground floor:

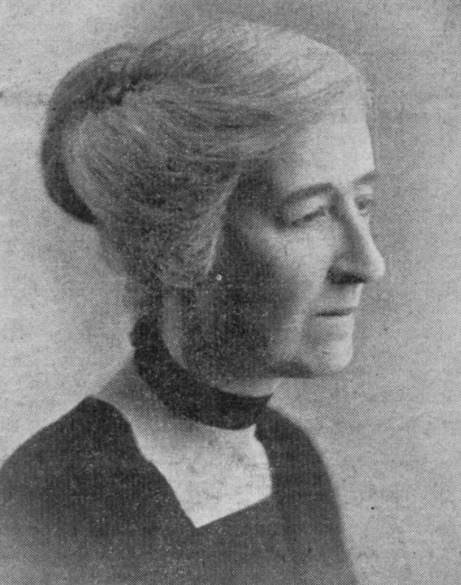

The plaque states that Lady Dorothy Nevill lived in the house from 1873 to 1913:

Born in 1826, she was the daughter of Horace Walpole and Mary Fawkener.

When she died in 1913, obituaries stated that she was one of the more important links between the Victorian and present eras, and that she had lived through the reigns of George IV, William IV, Victoria, Edward VII and George V.

Her obituaries stated that she was “profoundly conscious of the fact that she was connected in blood with many of the leading families in England; but unlike most British aristocrats (remarks the Times), though a keen Conservative in politics, fully alive to the changes that time had brought upon English Society.”

Her support of Conservative politics was such that she “was one of the two or three ladies responsible for the founding of the Primrose League; indeed it is said to have been first suggested at her luncheon table; and every year on April 19 her windows and balconies were covered with primroses”.

The Primrose League (named after the favourite flower of Benjamin Disraeli) was founded in 1883 and was a Conservative supporting, mass membership organisation, formed to promote the aims of the Conservative party across the country, and support the election of Conservative candidates.

The success of the league was such that in ten years, membership had reached over one million, and there were members across the country, including the industrial towns of the north.

There were however, many sceptical of the organisation, and the Edinburgh Evening News on the 2nd of February 1884 was reporting that:

“That latest of Conservative follies, the Primrose League, is pushing its way. A considerable number of people have joined it, and its organisors assert that it will in the course of time become a powerful element of Tory reaction. It has been decided to start a branch of the League at Birmingham, with a view of assisting the candidature of Lord Randolph Churchill.

A correspondent suggests however, that an institution like the Primrose League is more suited for the atmousphere of Belgravia than Birmingham.

It was established by some rather weak-minded Conservatives in the West End of London, and it is not likely that it will be largely supported by the artisans of Birmingham. The League intends to hold a great demonstration on April 19th, the anniversary of Lord Beaconsfield’s death. There is some talk of its members walking through the metropolis in a monster procession.”

Surprisingly, the Primrose League lasted until 2004, when it was disbanded.

Her obituary also remarked that “The Sunday luncheon parties at her little house in Charles Street were the meeting place of people of all kinds of opinion, drawn from many walks of life, though she herself was fond of saying that her society was exclusive, dull people being never admitted”.

I like the description of her house in Charles Street being described as “her little house”, but I suppose that all things are relative for “The Quality”.

Whilst many of the buildings along Charles Street have changed significantly since the street was first developed, there are some original houses, and some of these have had some rather strange additions, such as this terrace house with a stone bay window that looks as if it has been randomly stuck on the building:

At the Berkeley Square end of the street there is, what the Historic England listing describes as “Two full height canted bays of 3 sashes each per floor and a 2 storey 2 window extension to left hand”. This is the rear of the Grade II listed 52 and 52A Berkeley Square, which date back to around 1750 and form part of the first development along Charles Street:

Charles Street is an interesting little street. Many of the buildings have an aristocratic heritage, as does the origins of the name of the Footman pub.

It is brilliant that the Footman survives, and the loss of the Red Lion is a shame. I do not know the reasons for the pub’s closure, but I often wonder in the planning decisions for pub conversions, just how much consideration is given to the change in use, and the loss of a community asset.

These converted properties often become trophy assets that add very little to the area.

Theoretically, it should now be much harder to get planning permission for the conversion of a pub.

The London Plan, published by the Mayor of London, includes “Policy HC7

Protecting public houses” which does appear to provide a strong framework for resisting the conversion of a pub to alternative uses, however I suspect there are always ways and means to get around such constraints.

On a positive note for the area, Charles Street is in the City of Westminster, which in the 2017 London Pubs Annual Data Note (part of the Greater London Authorities Cultural Infrastructure Report), and Westminster had the highest number of pubs of any borough in London with 430,

In second place was Camden with 230 and in third place was Islington with 215. Barking and Dagenham had the fewest number of pubs, with just 20.

I did not take any photos of the Red Lion when it was open, which I regret. You do not appreciate places until they are gone, and this is now one of the reasons why I probably take too many photos of even the most mundane street scene, as you know for sure, that within London – at some point it will have changed.