For today’s post, I am in Carlton House Terrace. It is one of my favourite types of post as I am looking for a place that has been demolished, the site has changed significantly, however I can still find part of a building that helps to confirm the location.

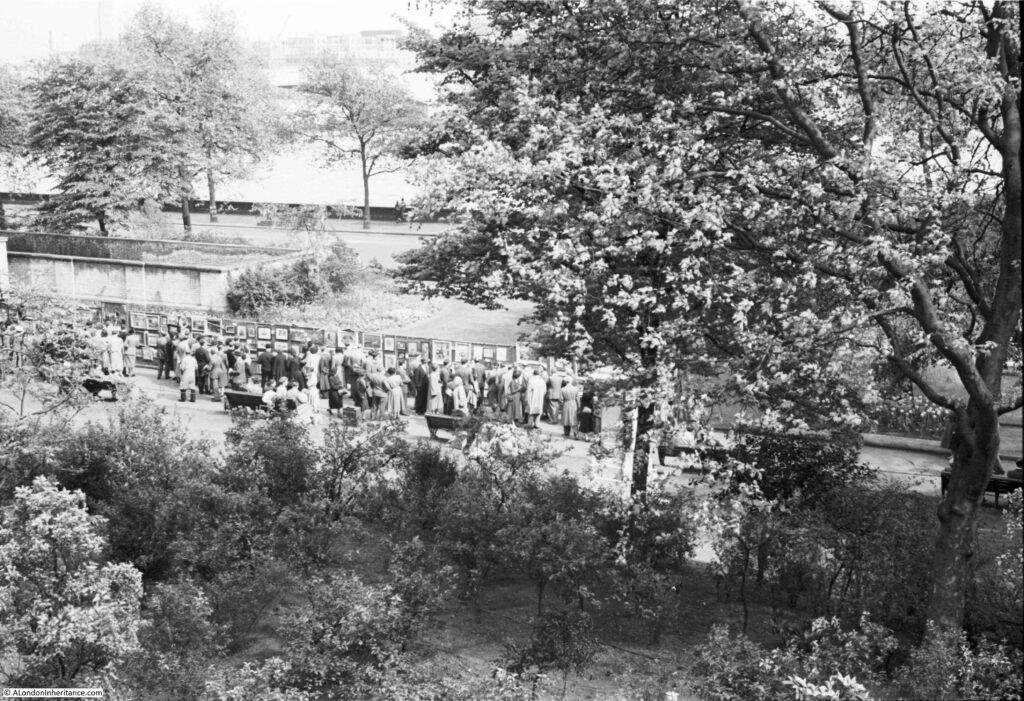

The following photo was taken by my father in 1949, and shows a house in some form of courtyard, with some steps to a street on the right.

The location should be easy to find as the house has the address 22A Carlton House Terrace next to the door. The photo appears to have been taken from underneath some form of archway.

As well as finding the location of the above photo, I took a walk through the area to the north of Carlton House Terrace to explore the stairs and streets which few people seem to walk.

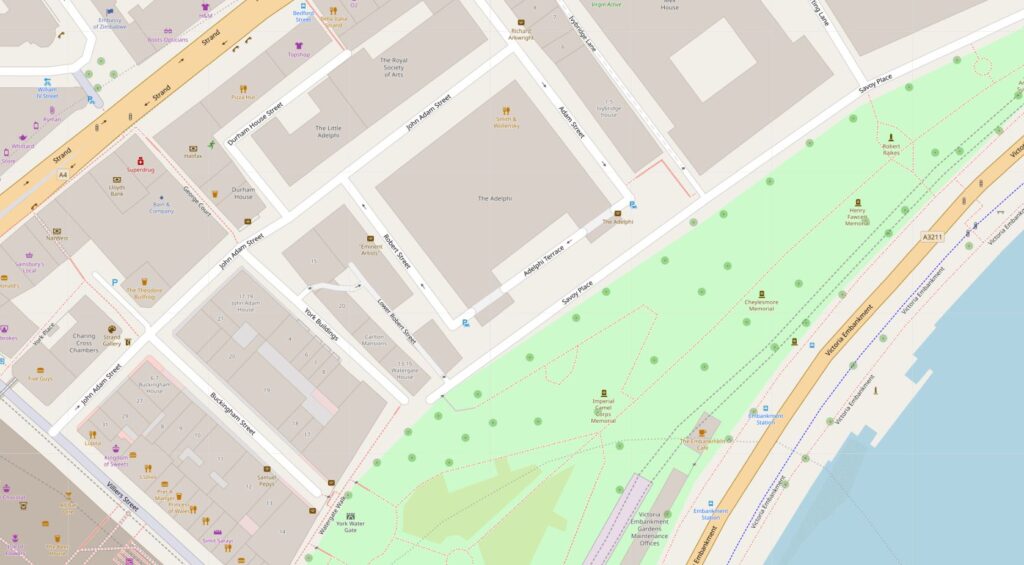

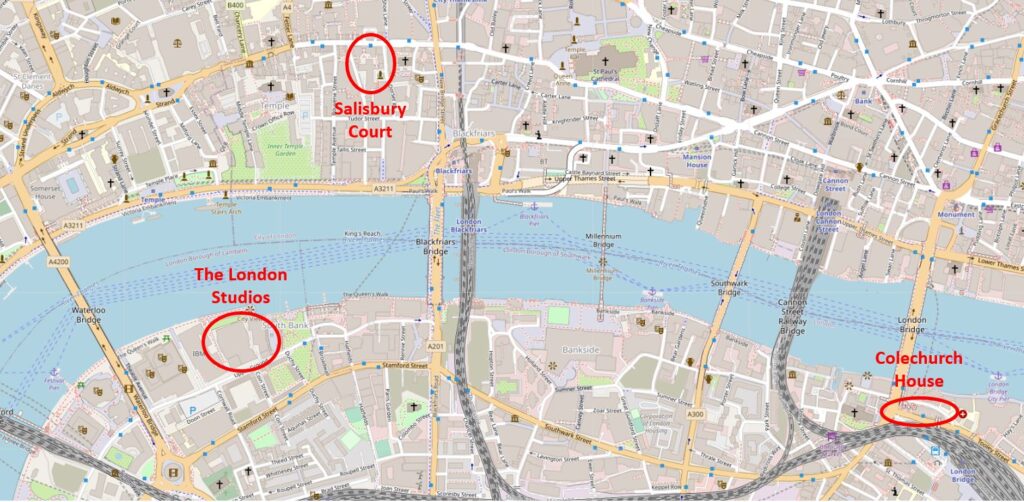

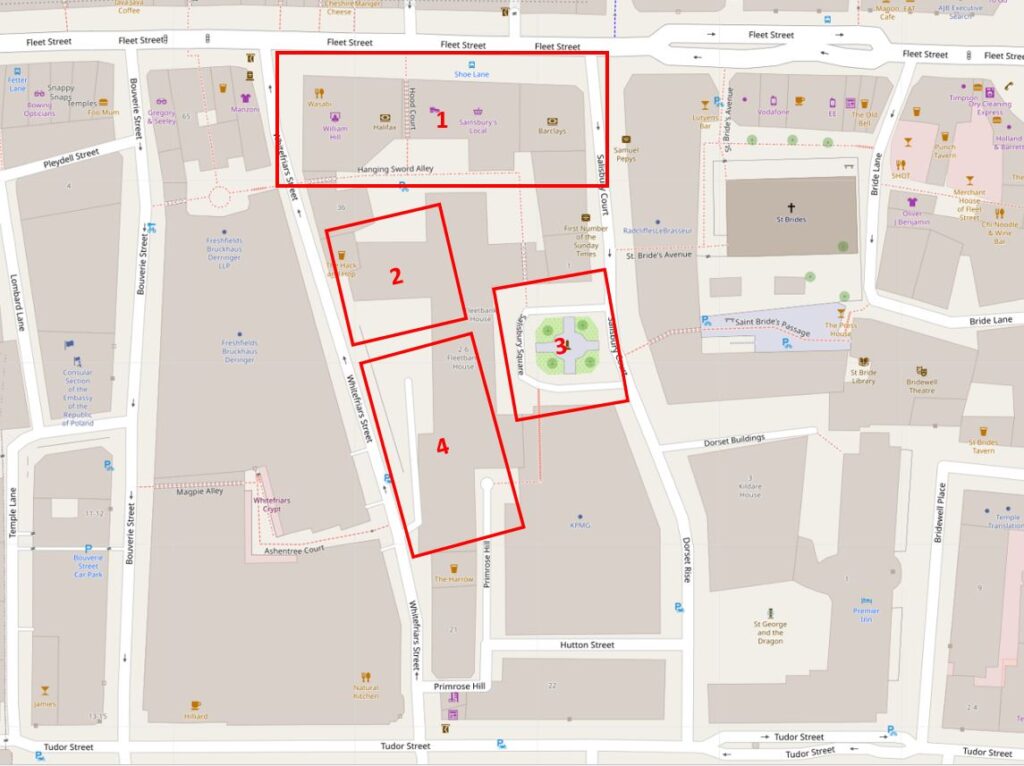

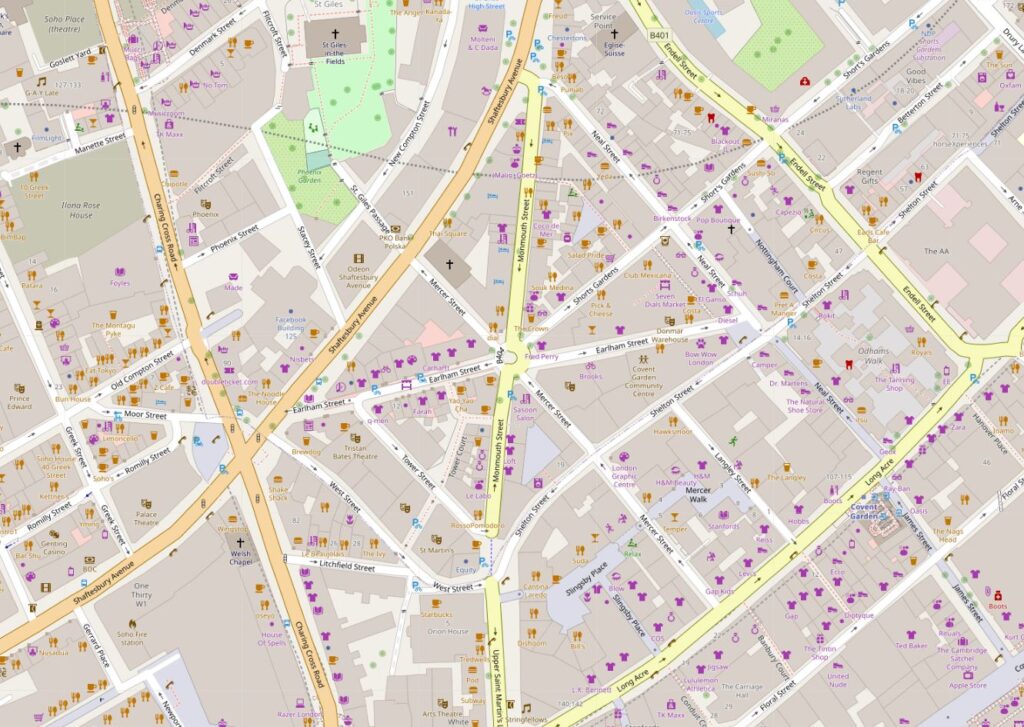

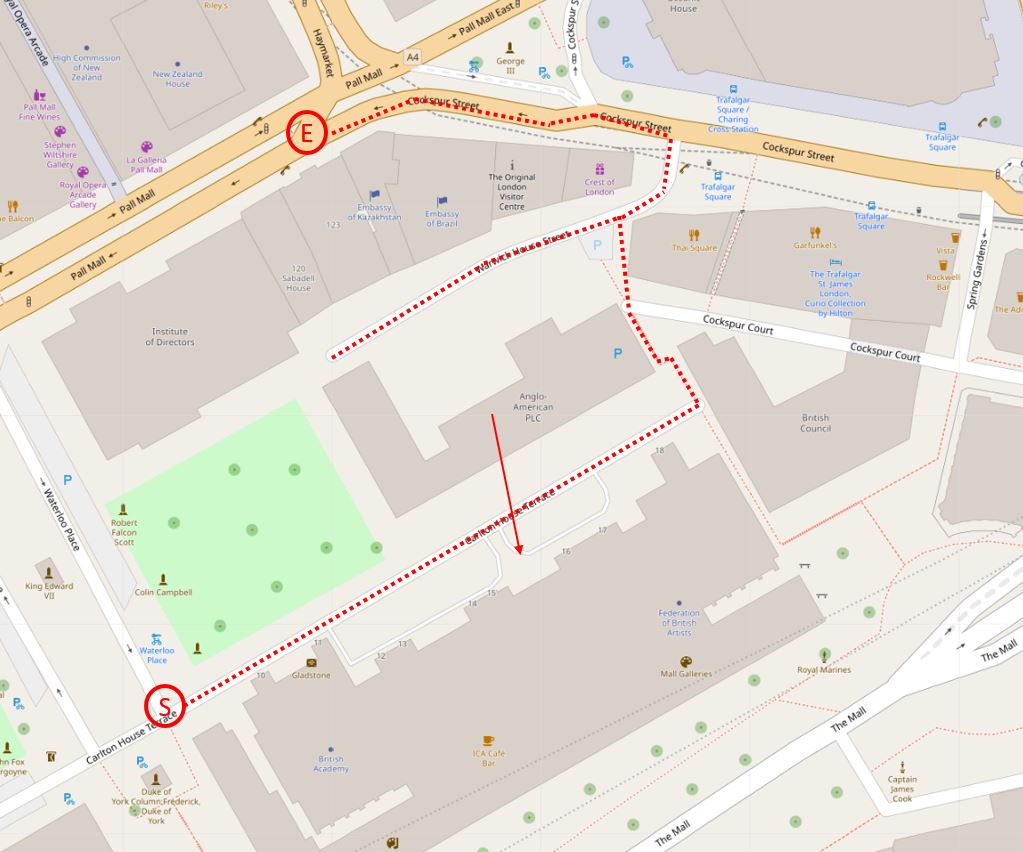

The following map shows my route, starting at S, where Carlton House Terrace meets Waterloo Place, and ending at E, on Pall Mall. Also on the map, the arrow shows the location of the photo (start of the arrow) pointing in the direction of the stairs through to the wall seen in the background of the stairs in the 1949 photo. Although there is a very different building on the site today, I will explain how I found the location in the rest of the post (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

This is the view along Carlton House Terrace from the junction with Waterloo Place. The street is a dead end with no exit for vehicles.

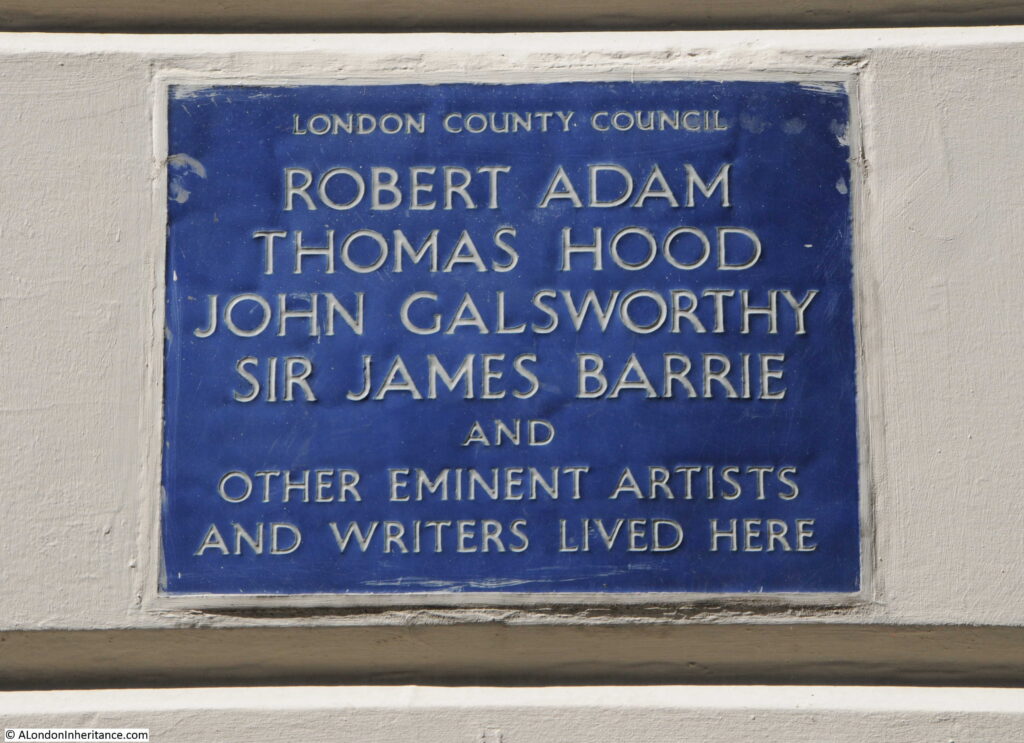

On the right of the above photo are the houses that were originally part of the plan by the architect John Nash to enhance the background to St James’s Park as the other side of the houses face onto The Mall, with the park on the other side.

Although part of the plans developed by Nash, much of the terrace seems to have been heavily influenced by architect Decimus Burton. The terrace was constructed in 1831.

Carlton House Terrace consists of a run of terrace houses, divided by the stairs that lead down from the end of Waterloo Place down to The Mall. The houses provide an impressive background to the northern edge of The Mall, however it is in Carlton House Terrace that we find the front of the buildings with their entrances and forecourts, and facades whilst not as impressive as on The Mall, still with considerable grandeur.

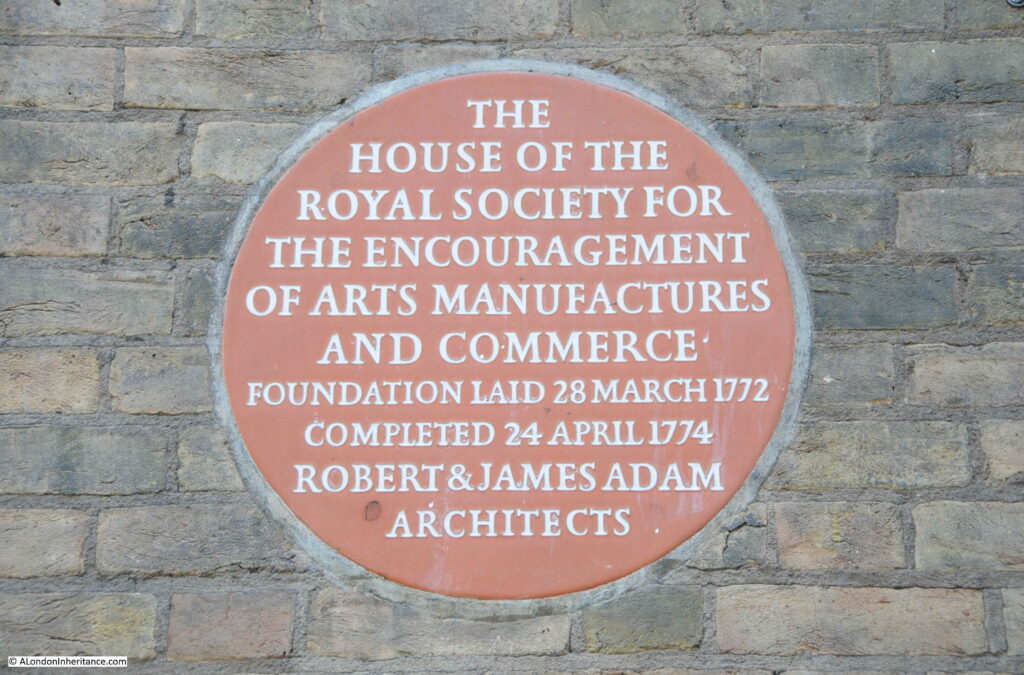

The round plaque in the above photo records that William Gladstone, the Liberal politician and Prime Minister lived in the house.

The view along the southern edge of Carlton House Terrace. The rear of these buildings face onto The Mall:

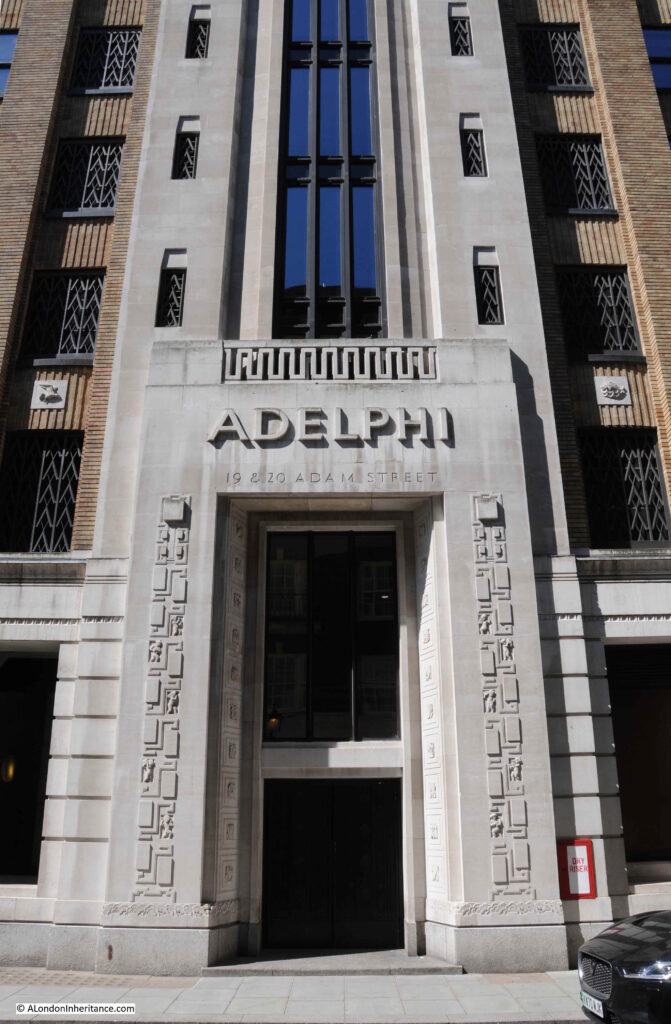

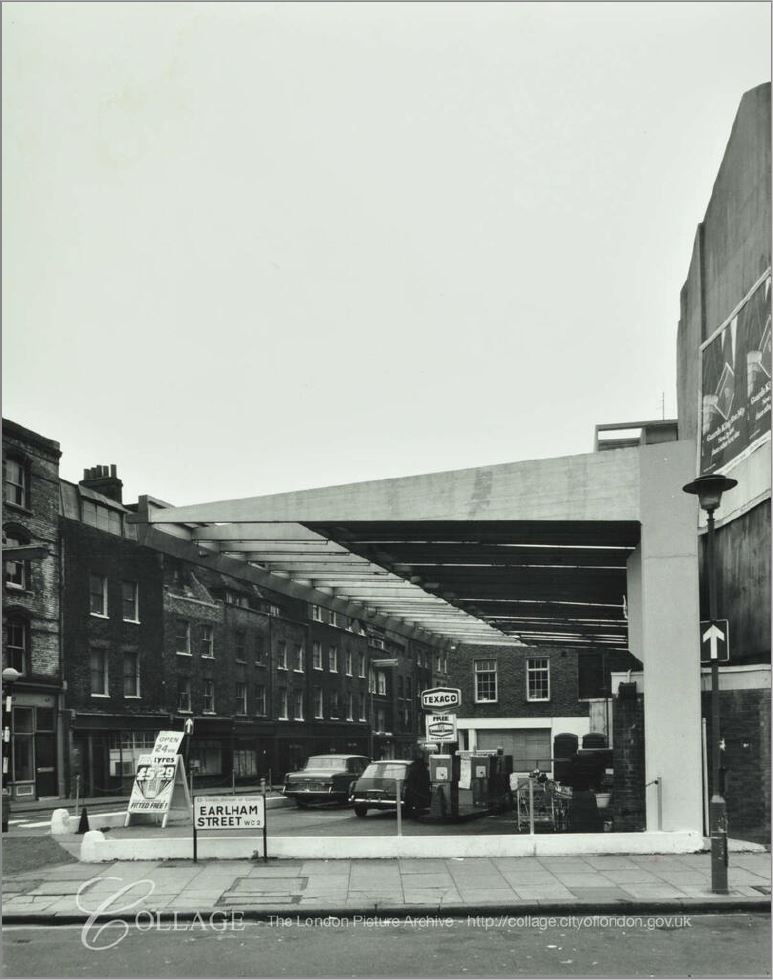

On the opposite side of the street is a relatively modern development. The number on the first building – 24 Carlton House Terrace – shows that the building is close to the 22A in my father’s photo.

A wider view of the northern side of Carlton House Terrace.

The large building on the left dates from the 1970s and is the former head office of the mining company Anglo American. It is this building that is on the site of my father’s photo.

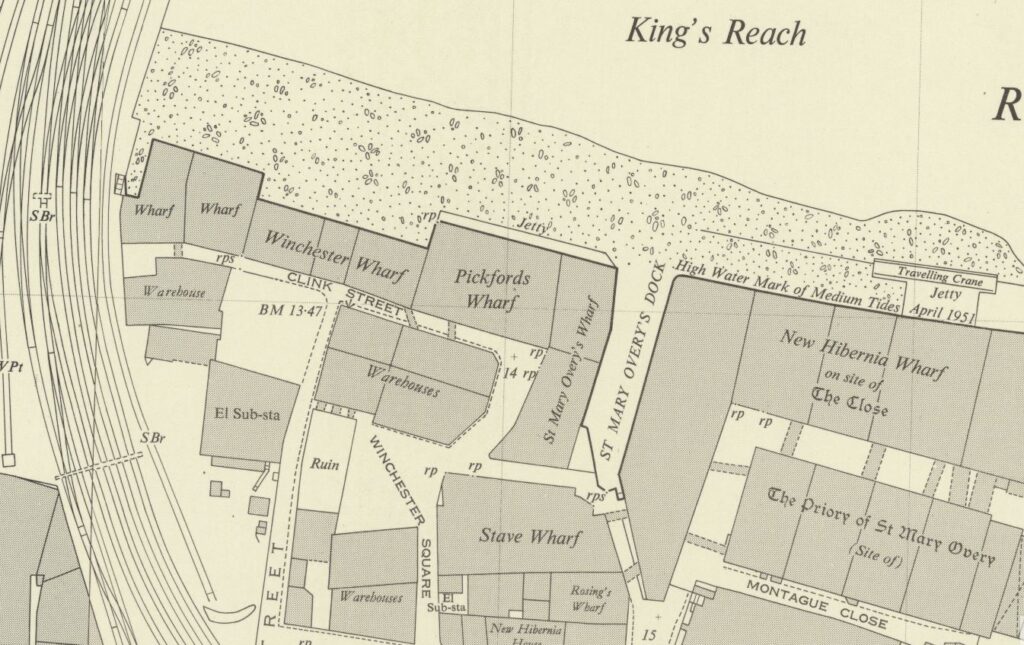

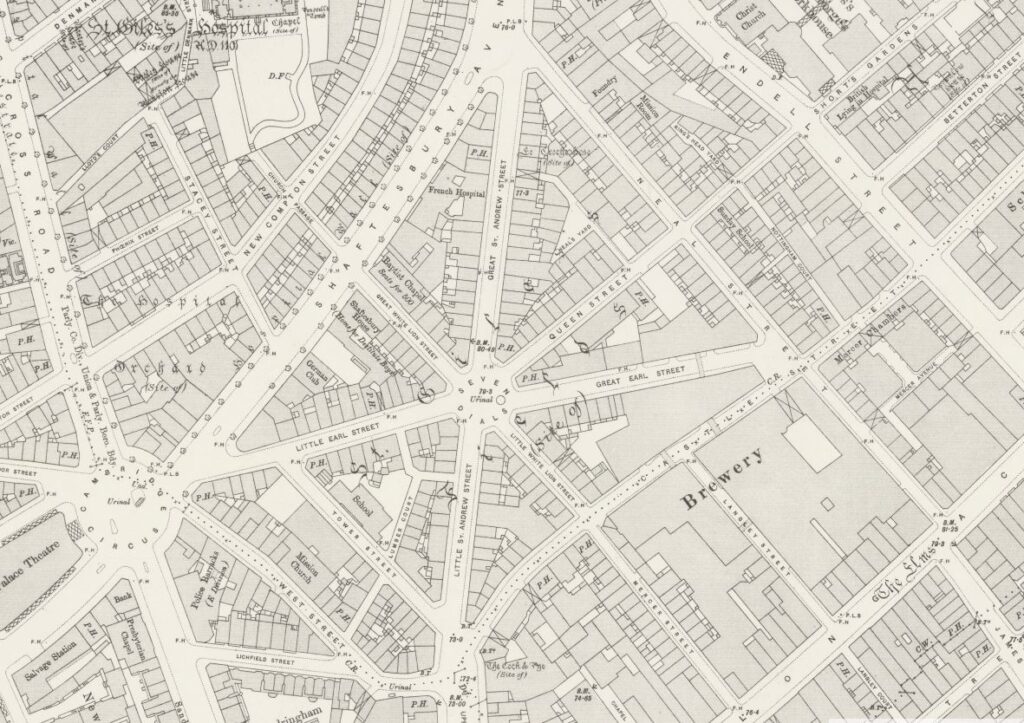

To identify the location, I turned to the 1951 revision of the Ordnance Survey map as this was only two years after my father’s photo.

In the following photo I have marked the position from where the photo was taken with the red dot (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

The red dot is under a feature which has an X arcros the dark grey for a building. The use of X is to show a building which has a walk / roadway through at ground level, and the buildings continue above. This explains the dark walls of such a feature on either side and above the immediate location of the 1949 photo.

Following the arrow across the open courtyard, and on the left of number 22A is the symbol for a set of stairs, exactly as seen in my father’s photo.

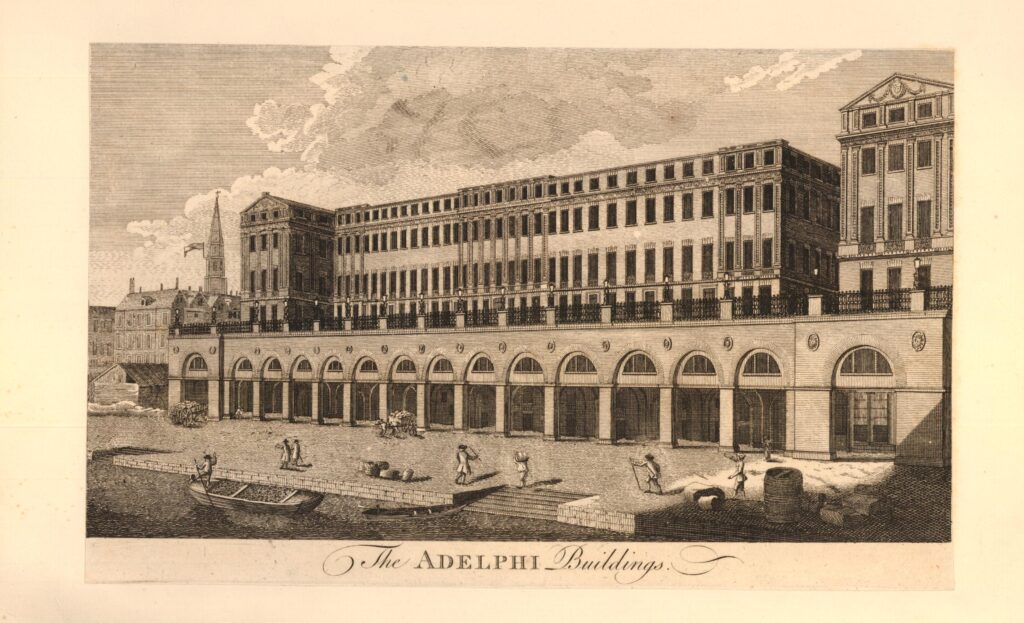

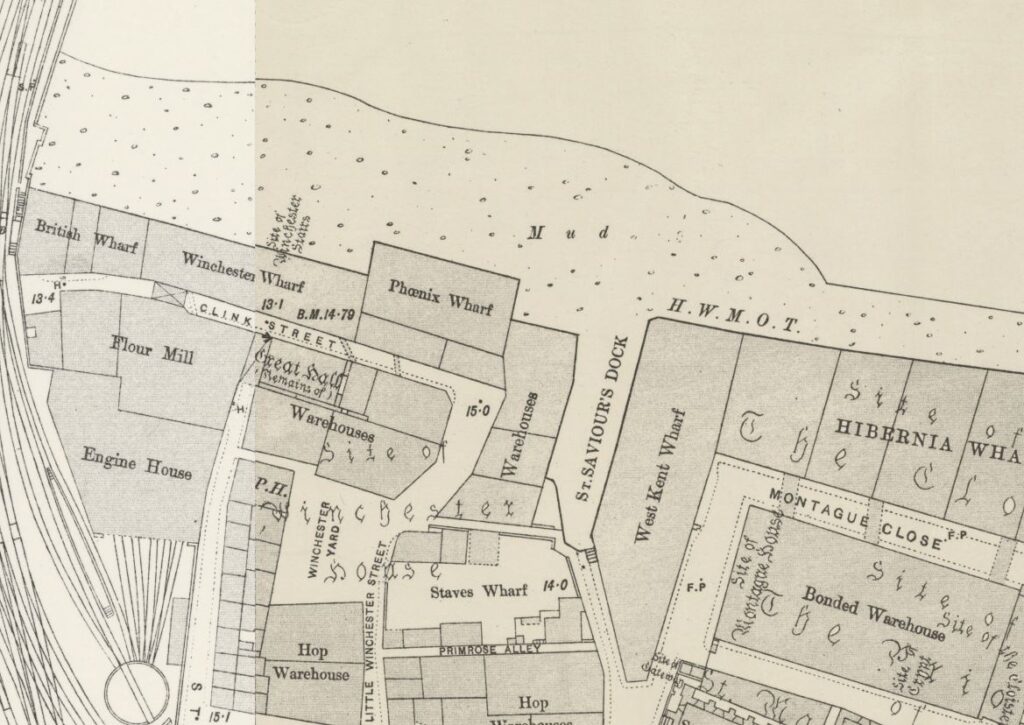

As usual, there is so much to discover in these maps. To the right of the above map is a building labelled “Old County Hall”. If we go back further to the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, we can see the same building labelled London County Council Office (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

This was the first offices of the London County Coucil after it was formed in 1889, and prior to the move to County Hall on the Southbank in 1922. Prior to the London County Council, the building was occupied by the Metropolitan Board of Works, which the London County Council replaced.

The above 1895 map also shows the same features as the 1951 map, providing confirmation of the same features in my father’s photo.

if you look at the above two maps, the arrow in the first map is pointing to the houses on the south side of Carlton House Terrace, and there is a curving feature to the edge of the forecourt in the centre of the terrace.

The same feature can be found today, with the railings curving from street to building:

My father’s photo is looking towards some stairs which lead up to Carlton House Terrace, and through the gap above the stairs we can see part of the wall of a building.

To the left of the hut in the above photo is a drain pipe, and this can also be seen above the stairs. In the following photo, I have outlined the area of wall in red and included an extract from the 1951 photo to show the same area of wall.

The following photo is from the south side of Carlton House Terrace, in front of the building in the above photo, looking across to the location of the stairs in my father’s photo. If I have worked out the exact location correctly, the stairs were just behind the car in the middle of the photo.

The above building was built during the 1970s. I cannot find when the buildings, courtyard and stairs in my father’s photo were demolished, however I suspect they were part of the demolitions to free up space for the building which now covers much of the northern side of this stretch of Carlton House Terrace, and occupy a large area of space back to Warwick House Street.

The following photo is from the eastern end of Carlton House Terrace, looking back to the junction with Waterloo Place and the stairs down to The Mall. The Duke of York’s Column (dating from 1834) which marks the stairs to the Mall and the split between the two sections of the terrace can be seen in the distance.

The street and terrace are named after Carlton House, which occupied much of the space now occupied by Waterloo Place. Carlton House had a considerable area of gardens which covered the space where today we can find the two sections of the terrace, on either side of the Duke of York’s Column.

I will save the story of the house and the rest of the terrace for another post, as my walk explored a couple of the streets to the north, between the terrace and Cockspur Street / Pall Mall (see map at start of the post).

Although Carlton House Terrace is a dead end for traffic, there is an exit for pedestrians, with some stairs at the far north eastern corner of the terrace.

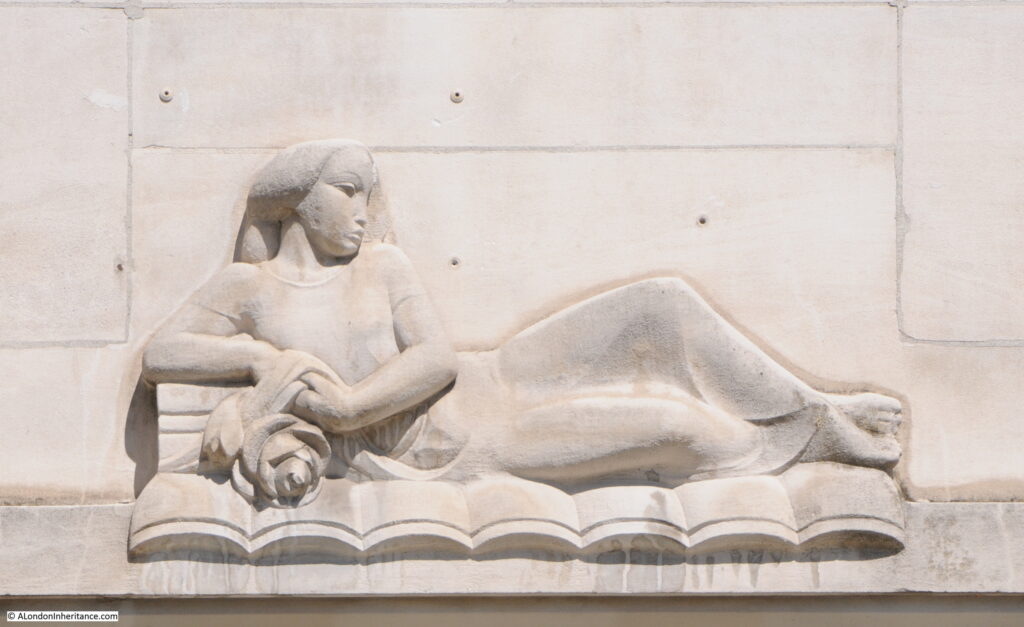

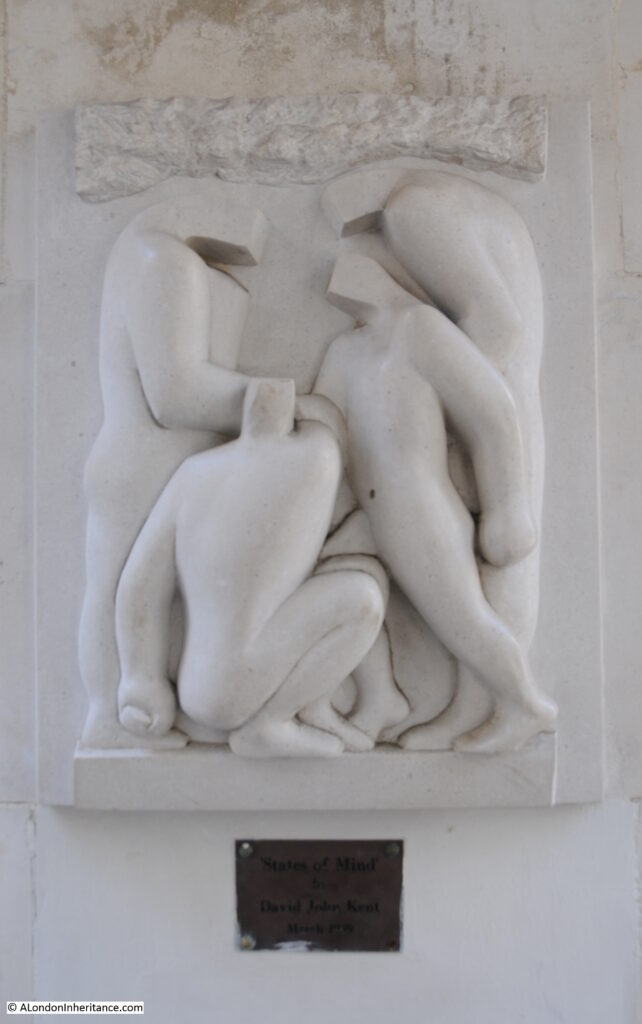

Looking back up the stairs, and there is an artwork by the sculptor David John Kent titled “States of Mind” at the top of the stairs:

Close up view of “States of Mind”:

The stairs take us into a short street called Cockspur Court that leads from Spring Gardens. Cockspur Court is a dead end, and its only function seems to be to provide a service access to the surrounding buildings.

In the centre of Cockspur Court appears to be the loneliest tree in London. No other trees within view, and a tree that must spend much of its time in shade due to the height of the surrounding buildings.

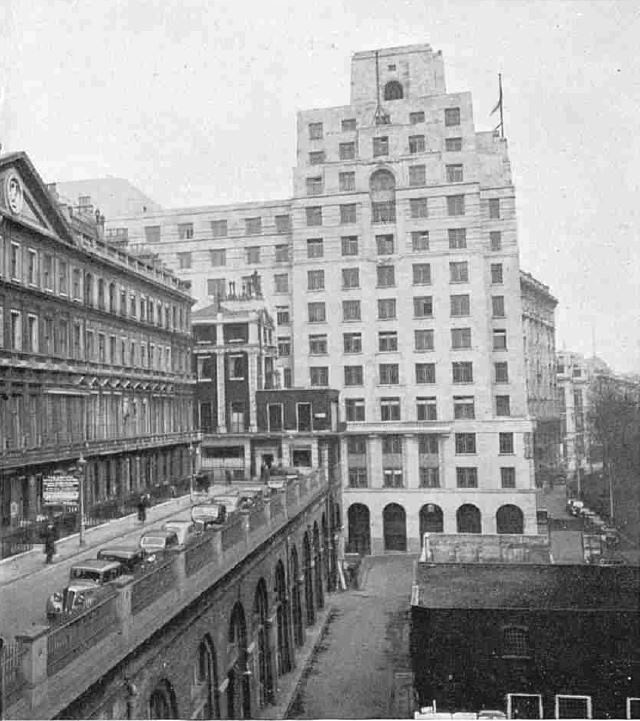

Looking across the court, and a building on the far side has the words “Grand Trunk Railway” displayed.

The following photo was taken towards the end of Cockspur Court, looking back towards Spring Gardens, again showing the lonely tree. The stairs down from Carlton House Terrace are behind the tree, and the large building behind the tree, and also running over Cockspur Court is the British Council Building, much of which occupies the space where the first London County Council building was located.

Although a dead end for vehicles, at the end of Cockspur Court, there is another set of steps:

Walking up these steps, and between two buildings:

Which leads into Warwick House Street:

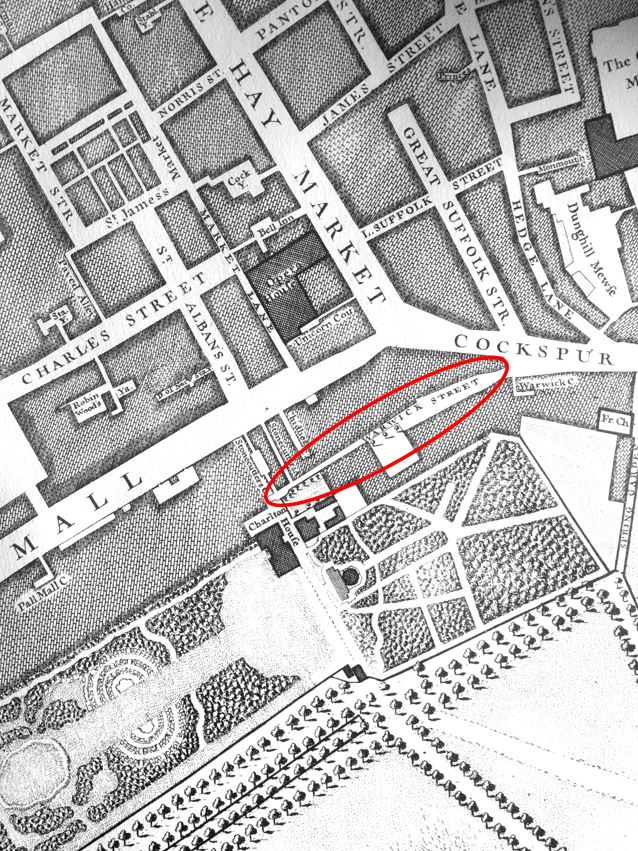

Despite appearing to be just a service road for the buildings on either side, Warwick House Street is actually a very old street, which predates Carlton House Terrace, and survives from the time of Car;ton House and the extensive gardens just to the south.

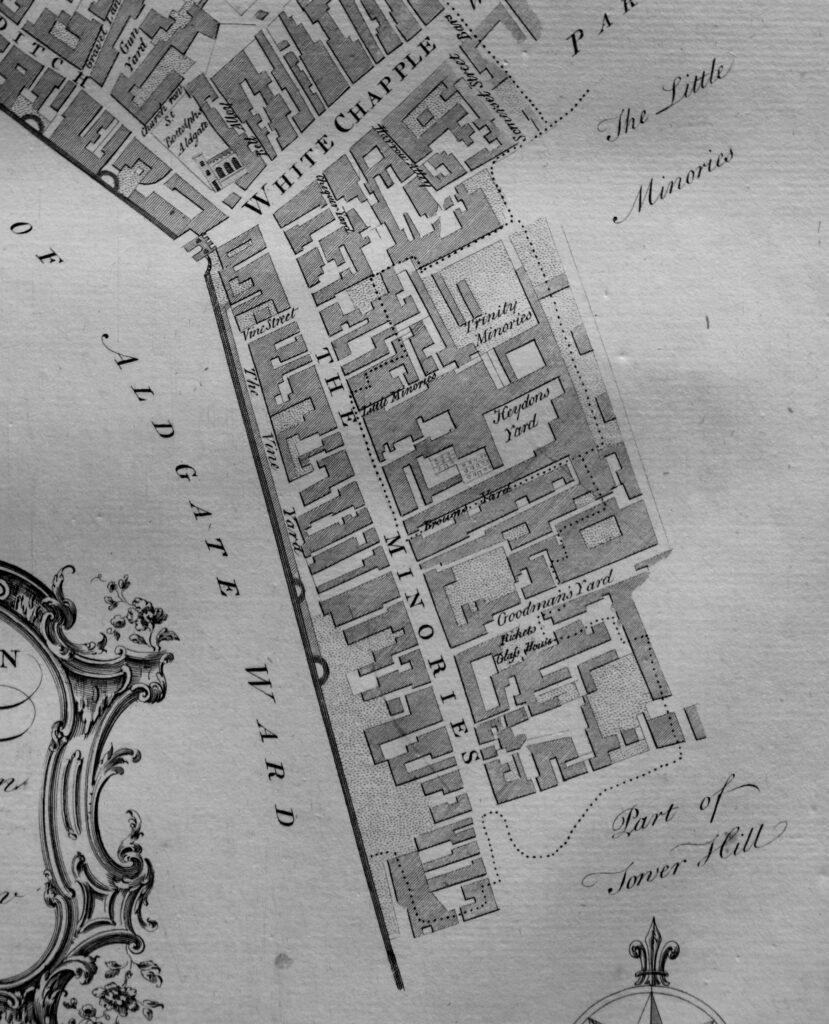

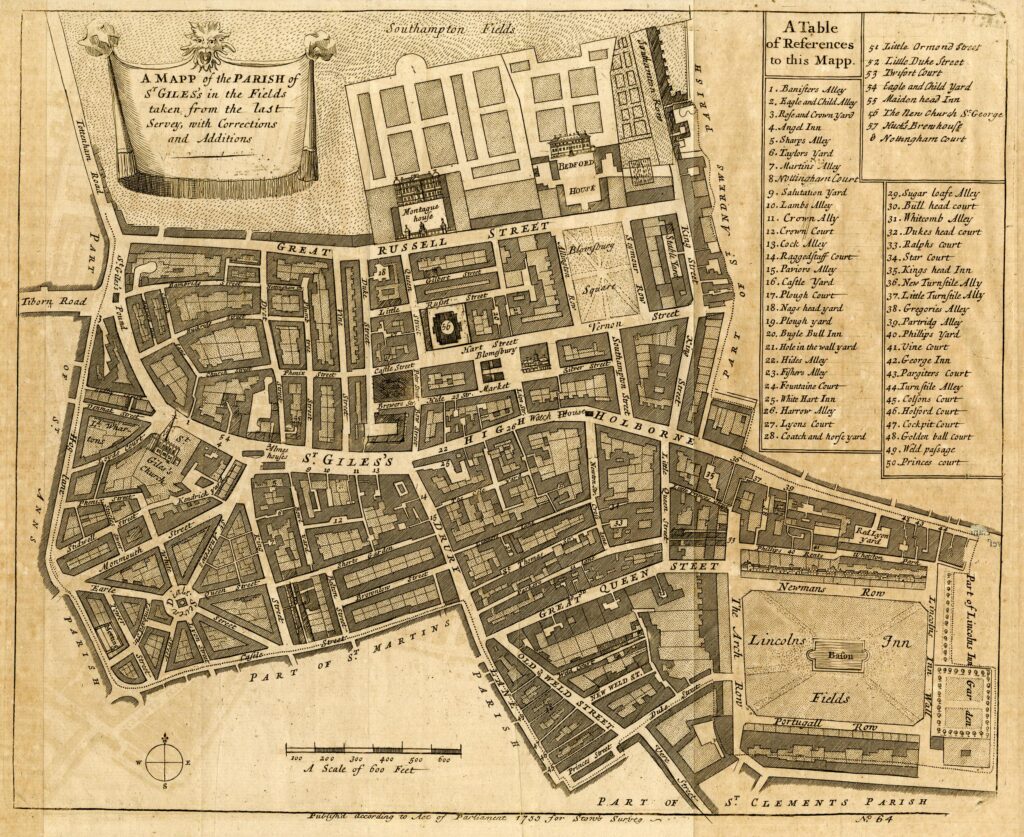

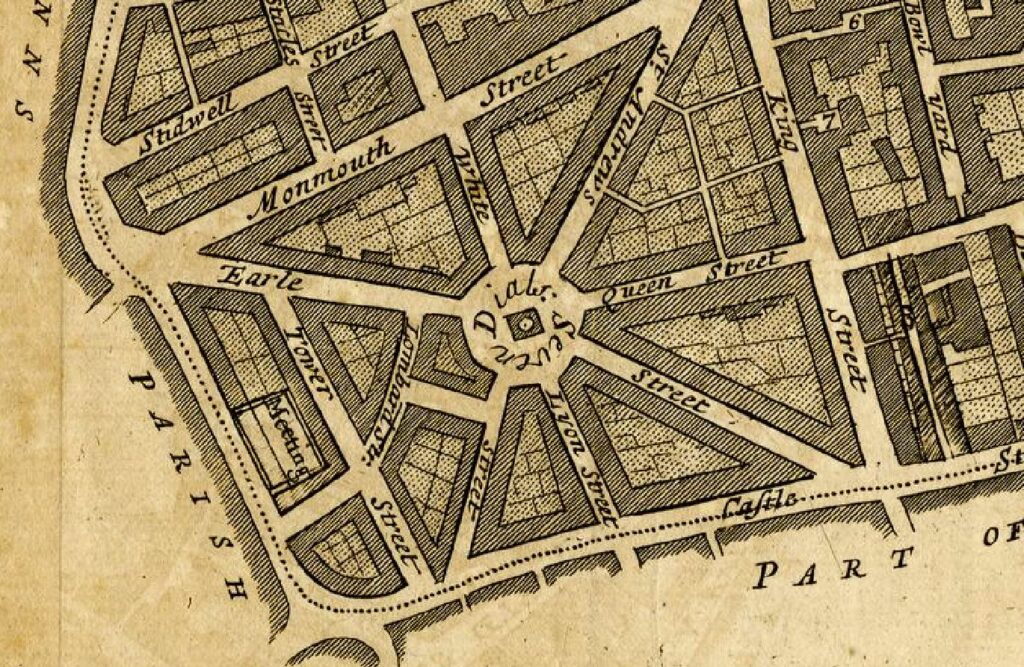

In the following extract from Rocque’s map of London from 1746, I have ringed Warwick Street, now Warwick House Street:

Referring back to the maps earlier in the post, it can be seen that the street follows the same route as the much earlier Warwick Street, apart from a slight change at the final junction with Cockspur Street.

In the 1747 map above, large gardens can be seen to the south. Carlton House Terrace now occupies this space.

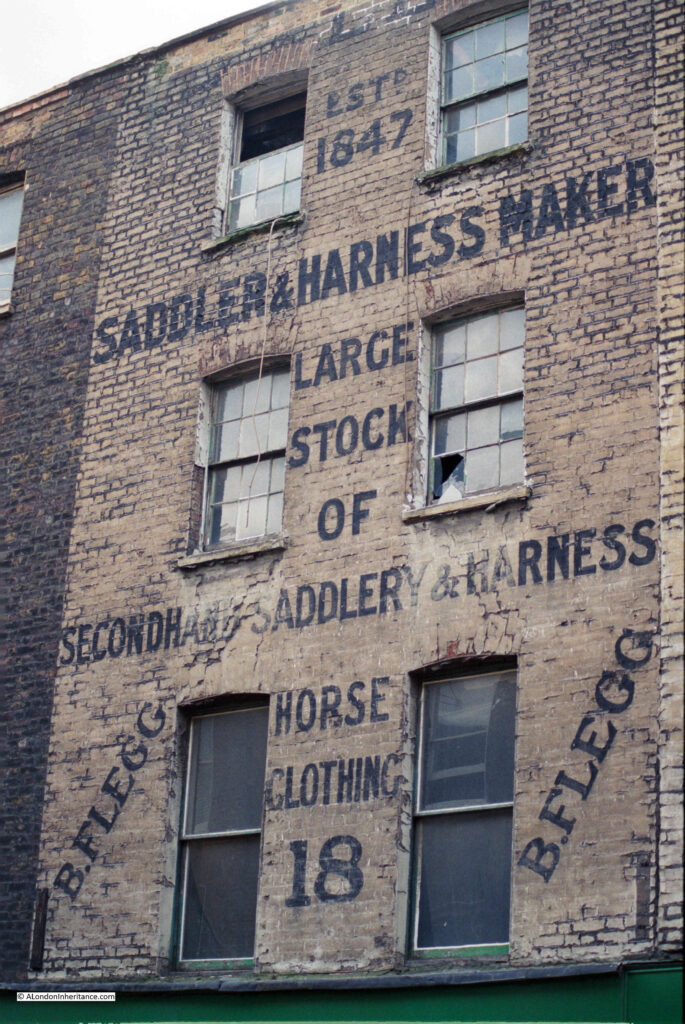

Warwick House Street consists of the backs of buildings that face onto other streets. To the north is Cockspur Street and Pall Mall, and there are a number of interesting buildings that have their backs on Warwick House Street, for example, this interesting mix of materials and shapes:

And on the same building that had “Grand Trunk Railway” displayed at the top, has “The Grand Trunk Railways of Canada” inscribed above the ground floor of the rear of the building:

Looking back along the street towards Cockspur Street and Trafalgar Square along a street that was here in 1746:

To take a look at the front of these buildings, I walked round to Cockspur Street.

The Brazilian Embassy occupies the buildings which has the ground floor with a mix of materials and shapes:

And the building with the railway references also has one on the front with the “Canadian National Railway Company”, the company that the “Trunk Railways” became part of. It is now the London Visitor Centre, and if I remember rightly, in the 1980s was the US Visitor Centre.

Confirming the building’s Canadian heritage, between the windows of the upper floors are the coats of arms of the provinces and territories of Canada:

I am pleased I found the location of the photo at the top of the post. Buildings and a view that have long been lost, however it is always good to find the exact location, and some remaining part of the view.

The sides streets are very close to Trafalgar Square, but are very quiet, mainly as they are basically service roads to the buildings on either side, but finding one that has been here since at least 1746 shows that whilst major houses and gardens come and go, and spaces are significantly reconfigured, in London, it is always possible to find traces of the past.