Fires have been a risk within London for centuries. Streets full of houses, side by side with warehouses full of inflammable goods, industrial premises, and until recently, a lack of comprehensive measures to prevent fire. The 1666 Great Fire of London is the most famous, however there were many others. I have written about the 1861 Great Fire at London Bridge, and today I want to feature another fire, the 1897 Great Fire in Cripplegate.

I have touched on the fire in previous blogs in an area I have covered a number of times as my father took many post-war photos of the area where the Barbican and Golden Lane estates are located, and it is fascinating being able to peel back the many layers of history of a specific area.

For today’s post, I am really grateful to a reader, who came on one of my walks and then sent me a number of newspapers and special editions, printed at the time of the fire to provide a record.

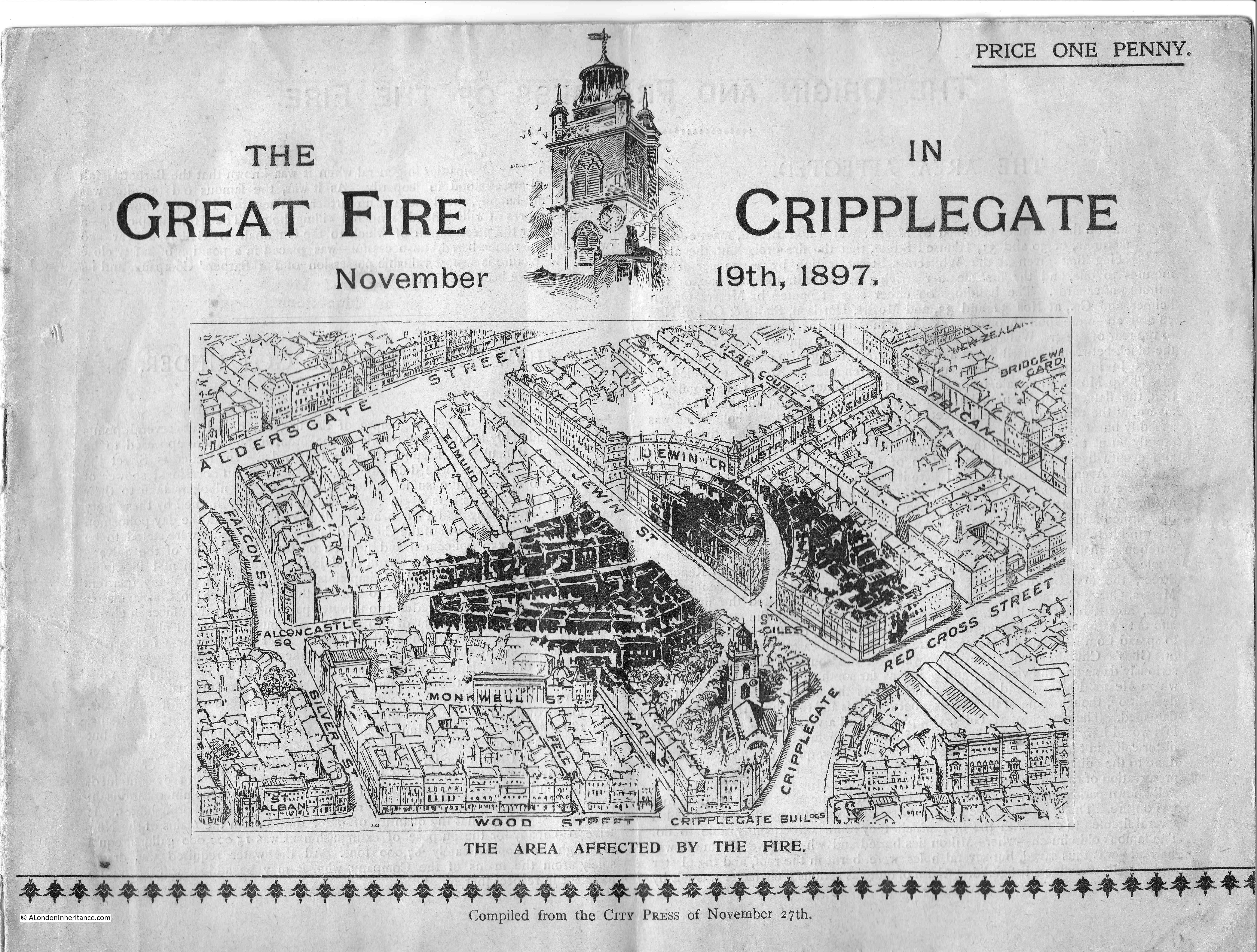

The cover of the City Press “Record of the Great Fire in Cripplegate”:

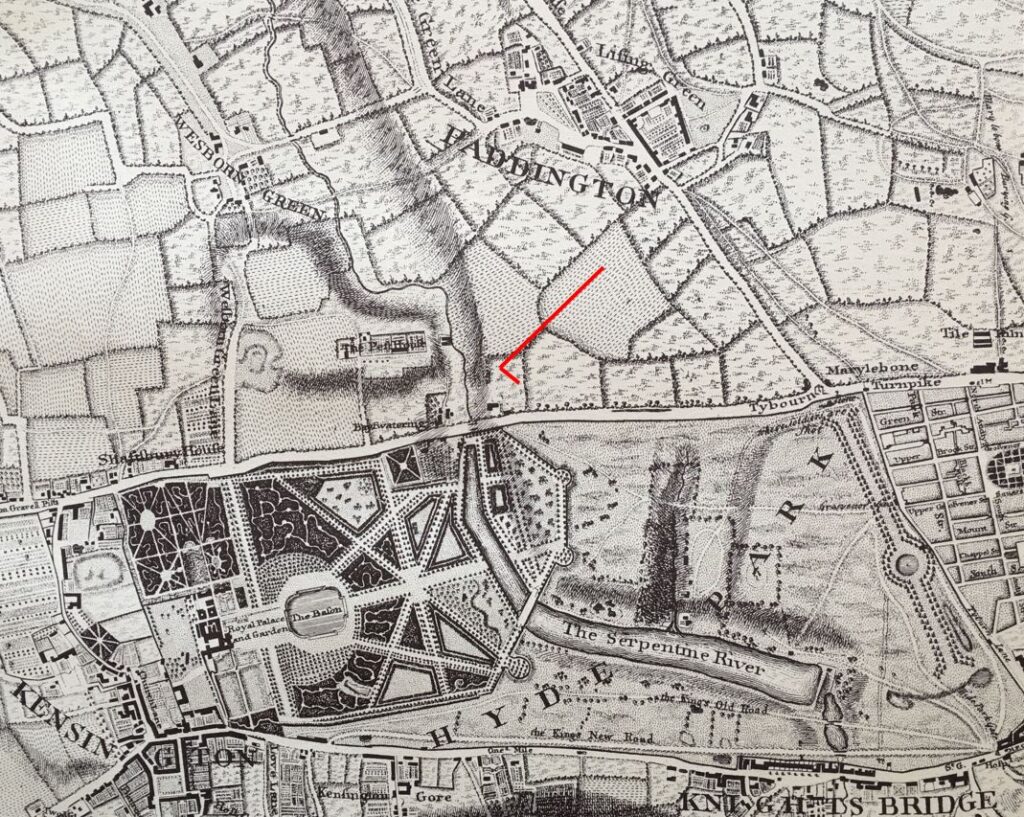

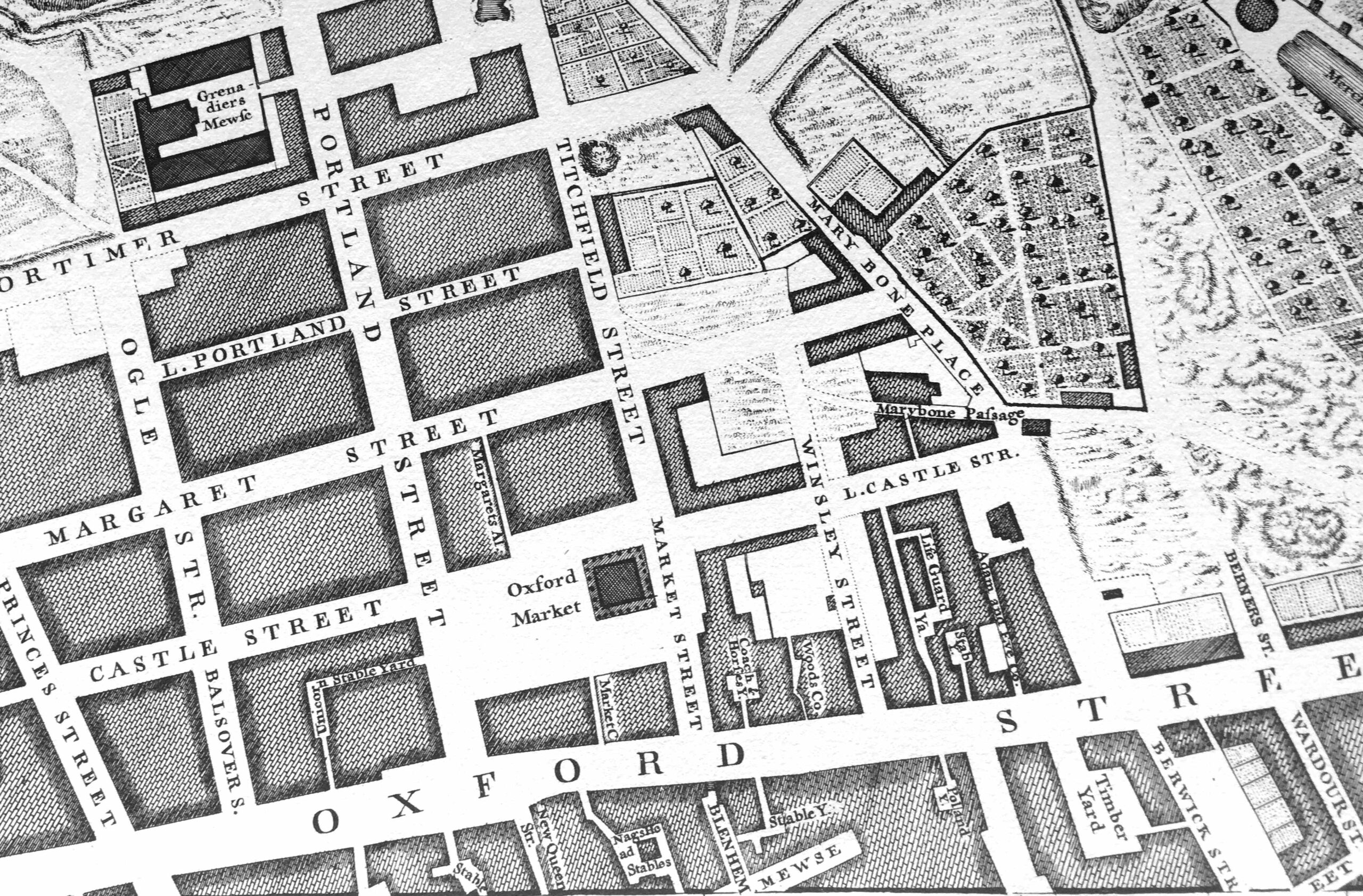

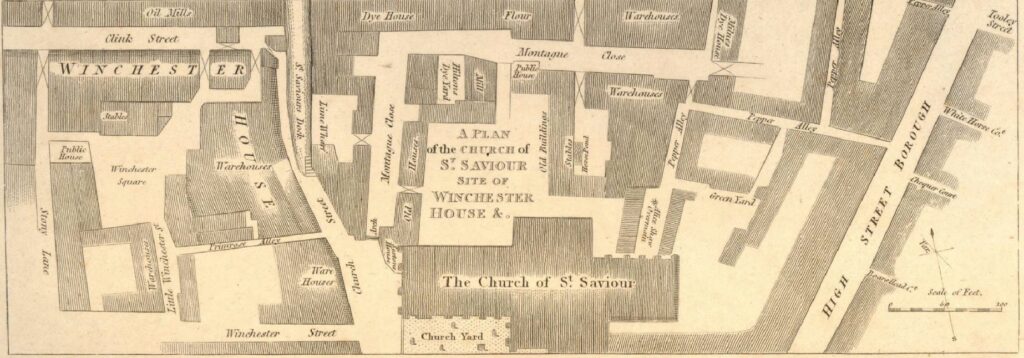

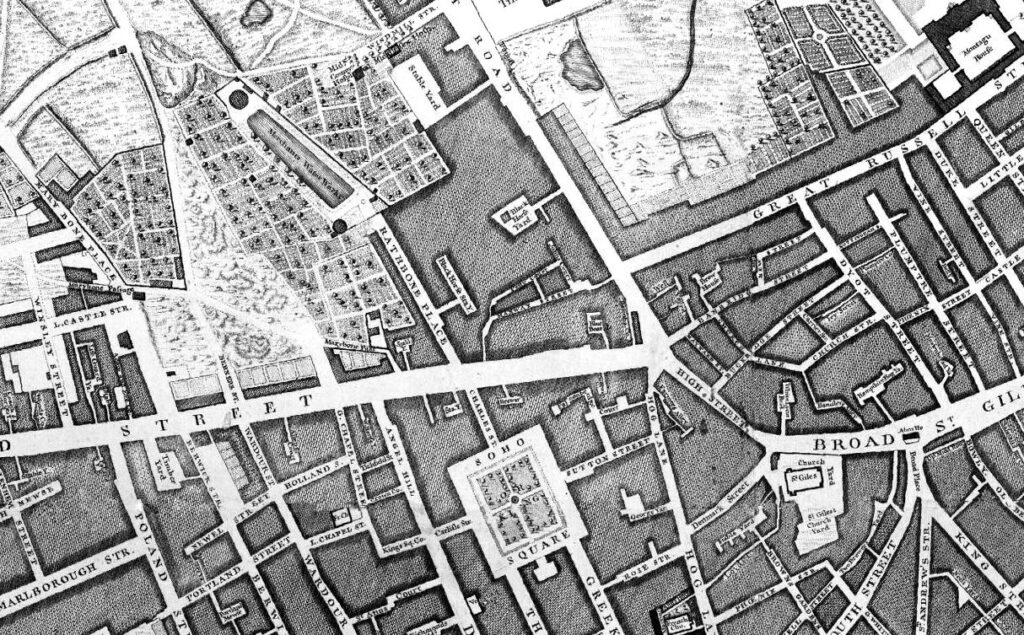

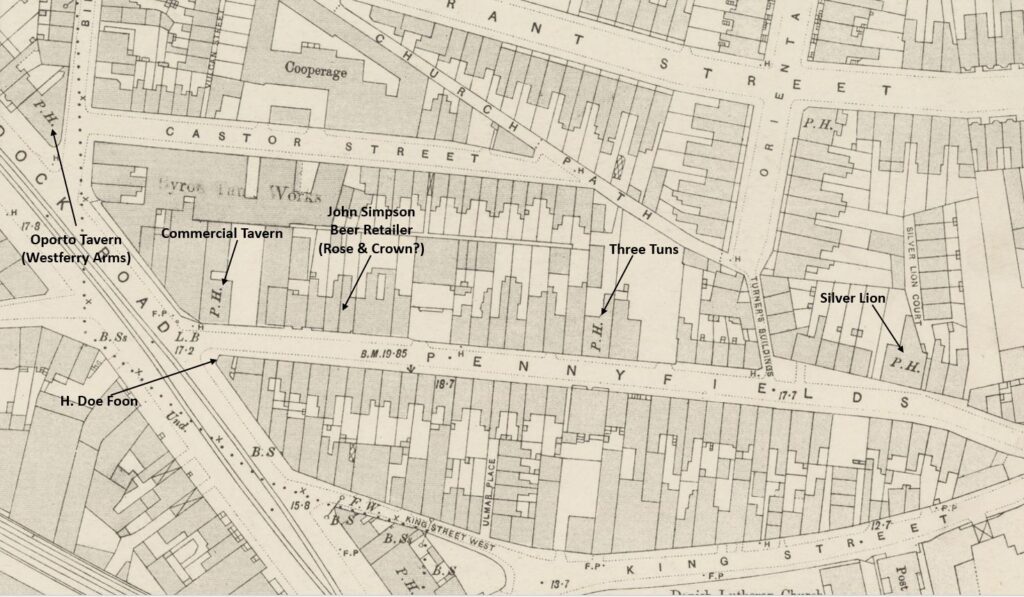

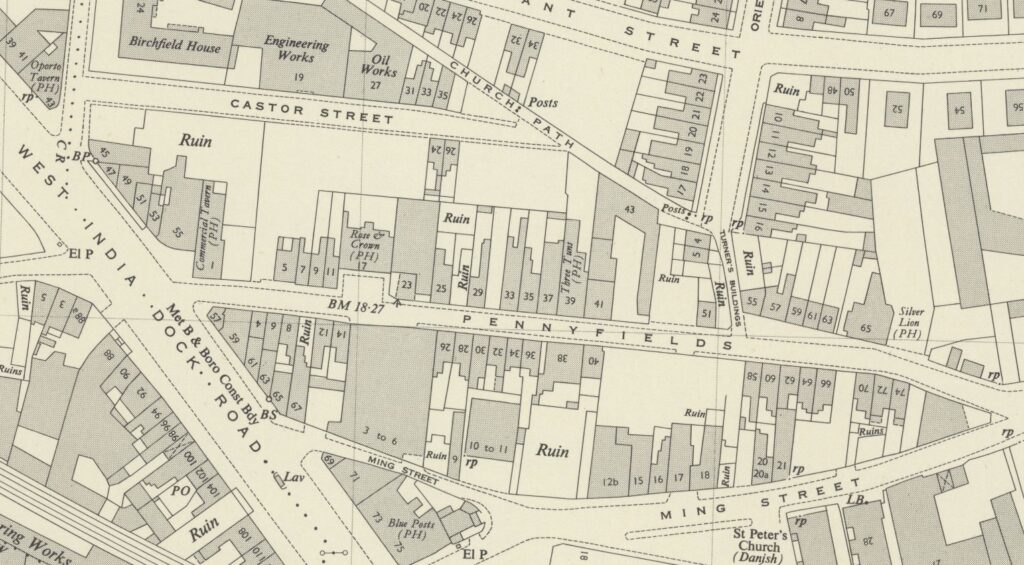

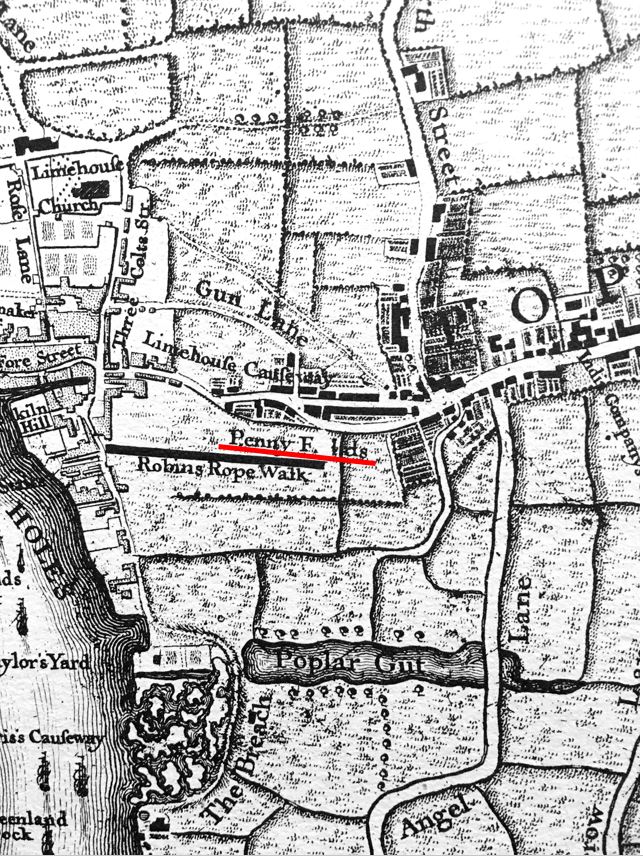

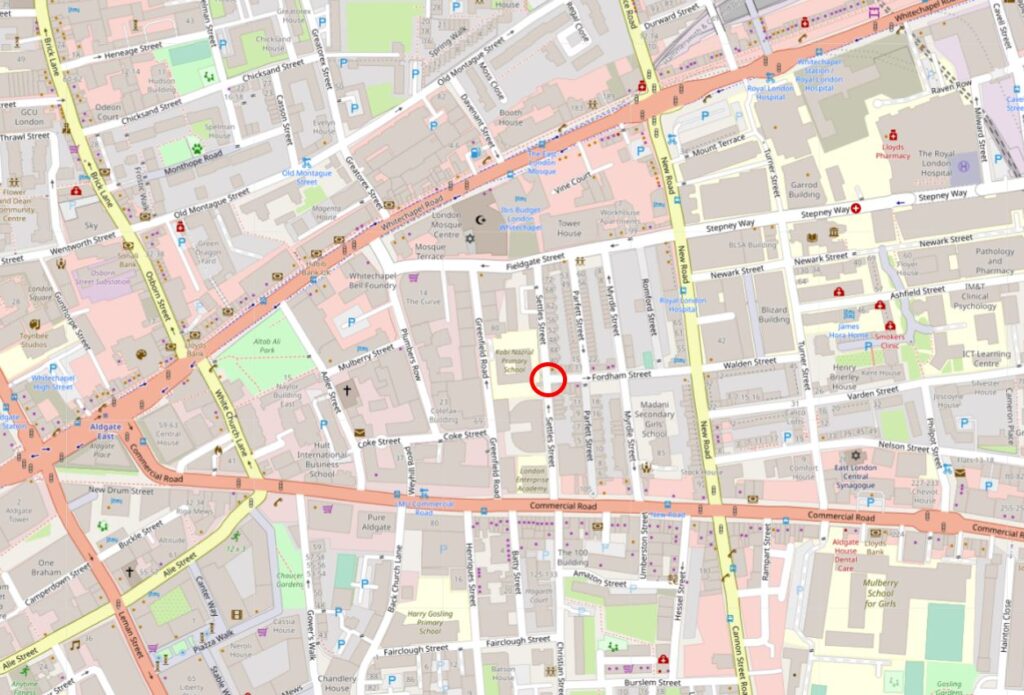

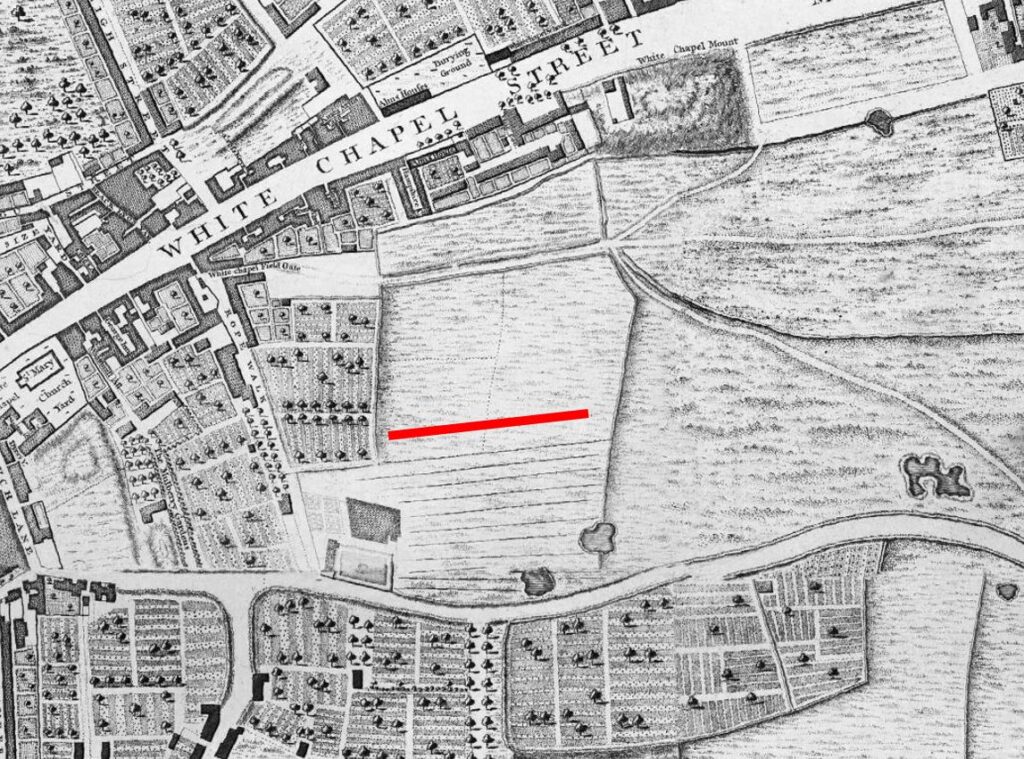

The cover of the booklet includes a map of the area affected, showing the buildings damaged by the fire in black. The map shows an area of busy streets with lots of housing, warehouses and industrial premises. This is so very different to the area today, which is now covered by the Barbican estate.

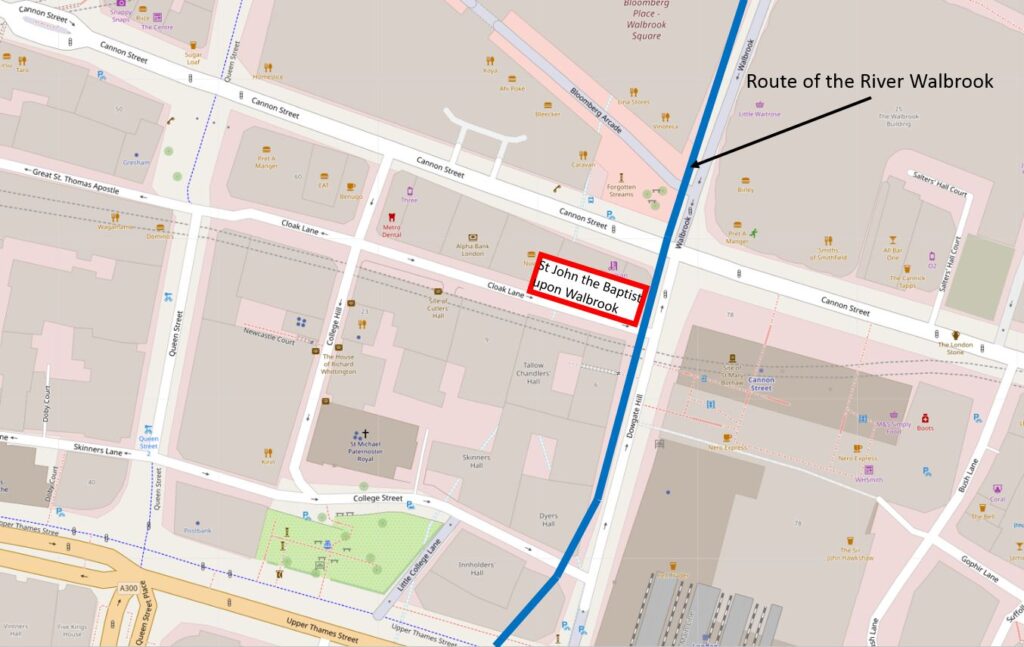

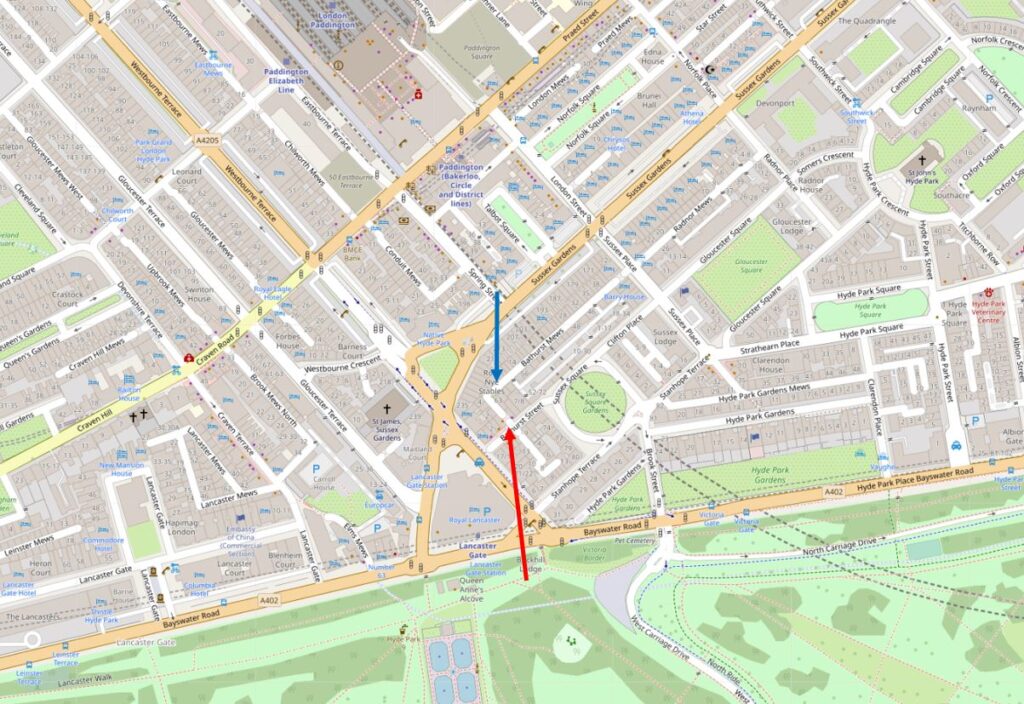

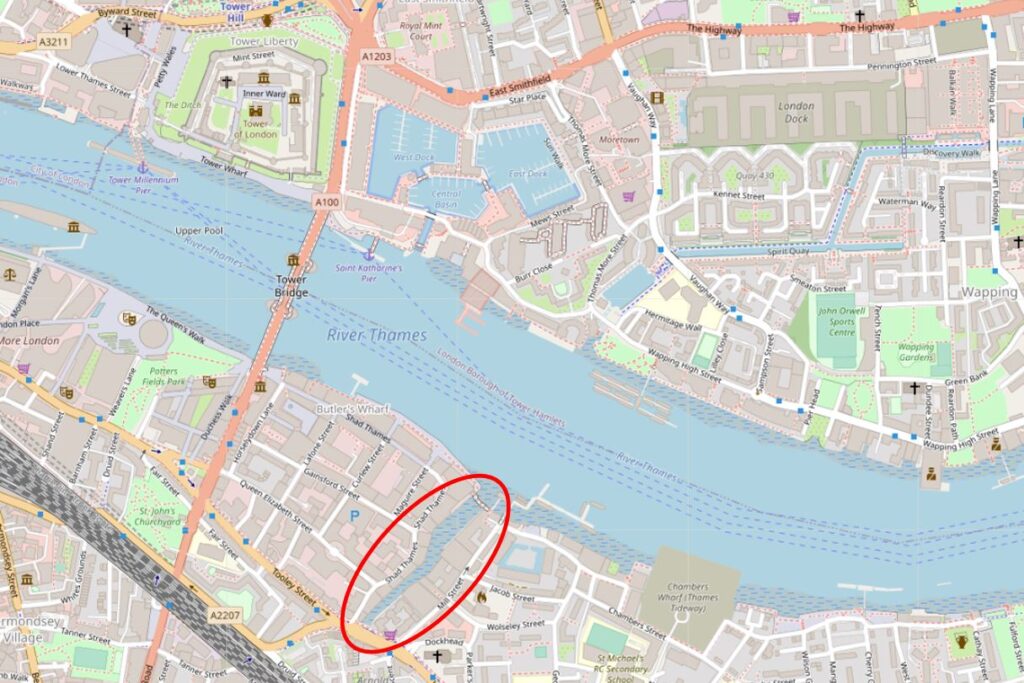

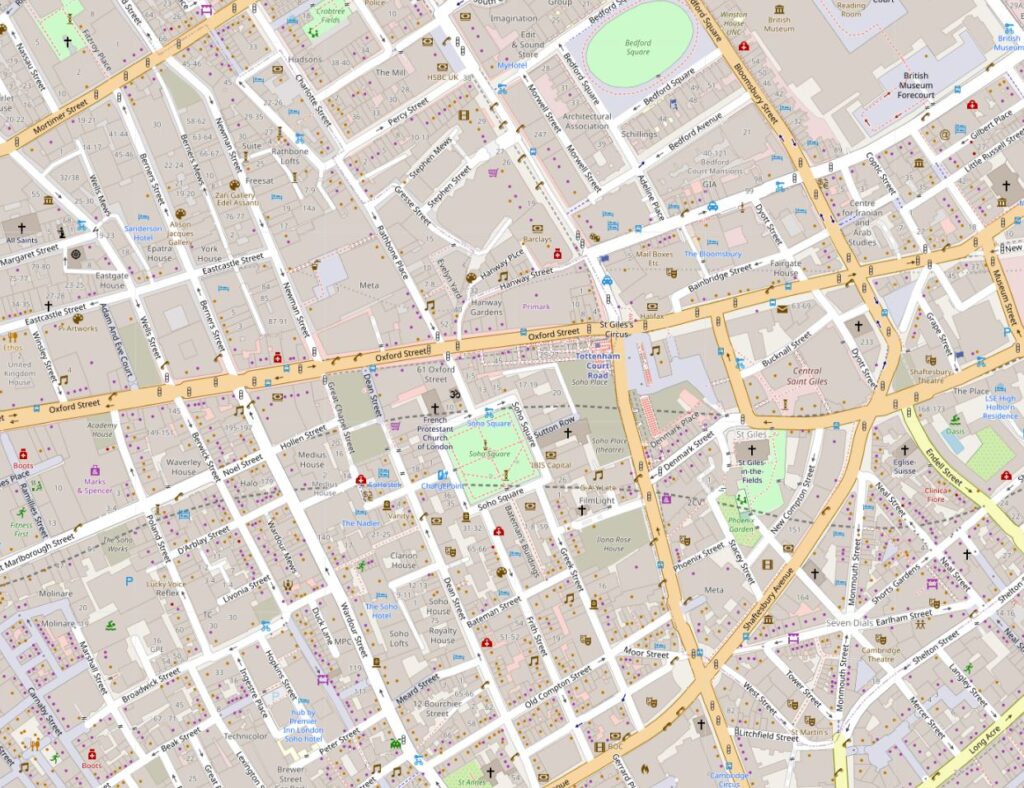

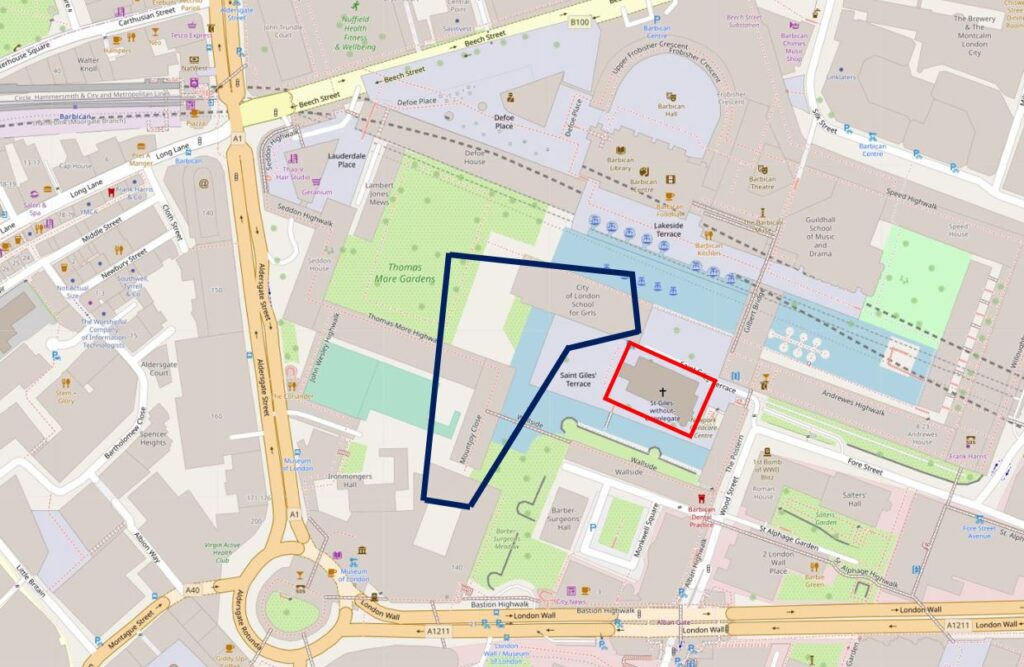

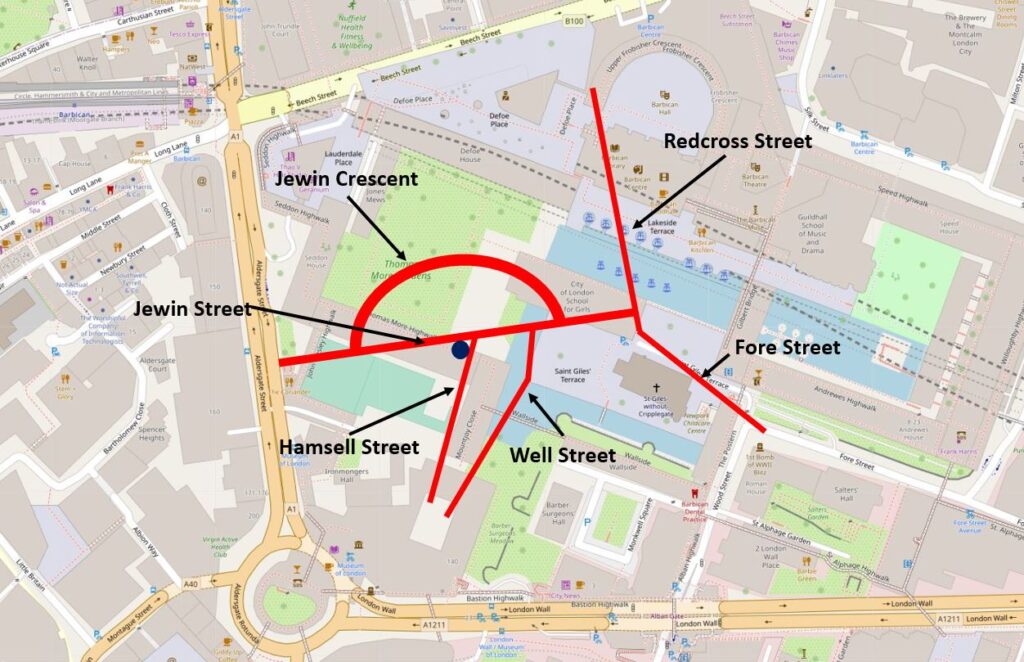

I have marked out the area of the Great Fire in Cripplegate within the dark blue lines in the following map. The church of St Giles Cripplegate (also shown in the above map) is within the red rectangle (© OpenStreetMap contributors).

The fire started in the premises of Waller and Brown at numbers 30 and 31 Hamsell Street, just before one in the afternoon. They were described as mantle manufactures, so presumably manufactured parts of, if not all of the components used in a gas lamp.

The report of the start of the fire states that most of the factory hands were out in the streets as it was lunch time, so perhaps someone had left a naked flame near some inflammable material as they went for lunch.

The fire spread quickly, with the buildings on either side of Waller and Brown’s building, soon being alight.

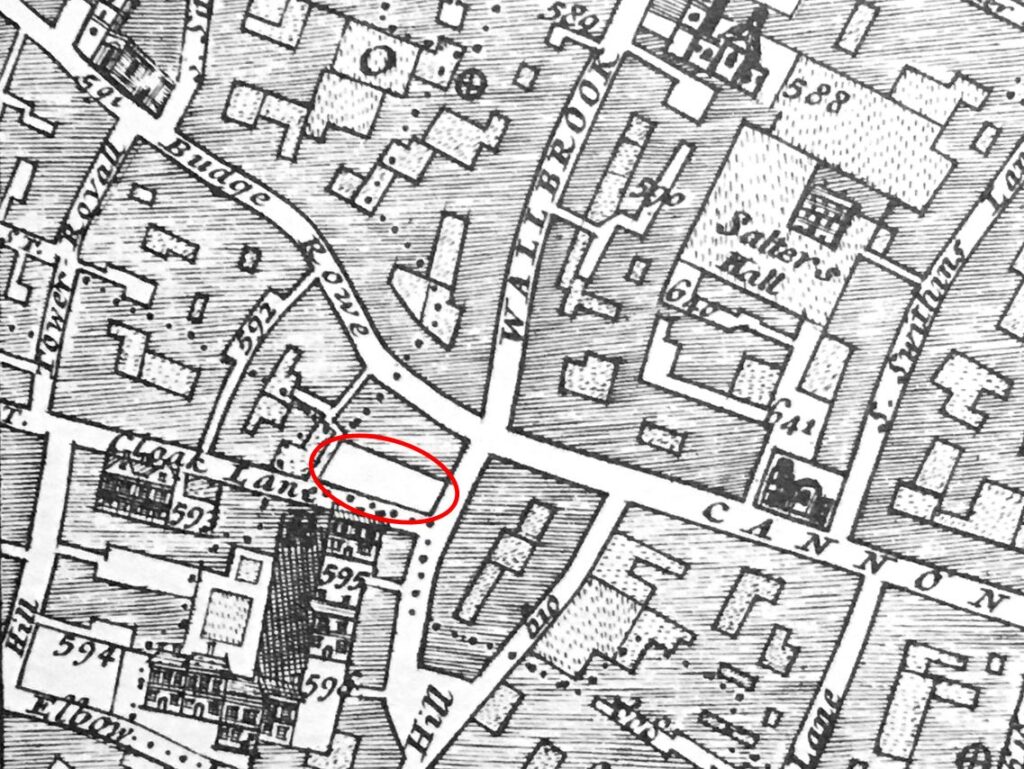

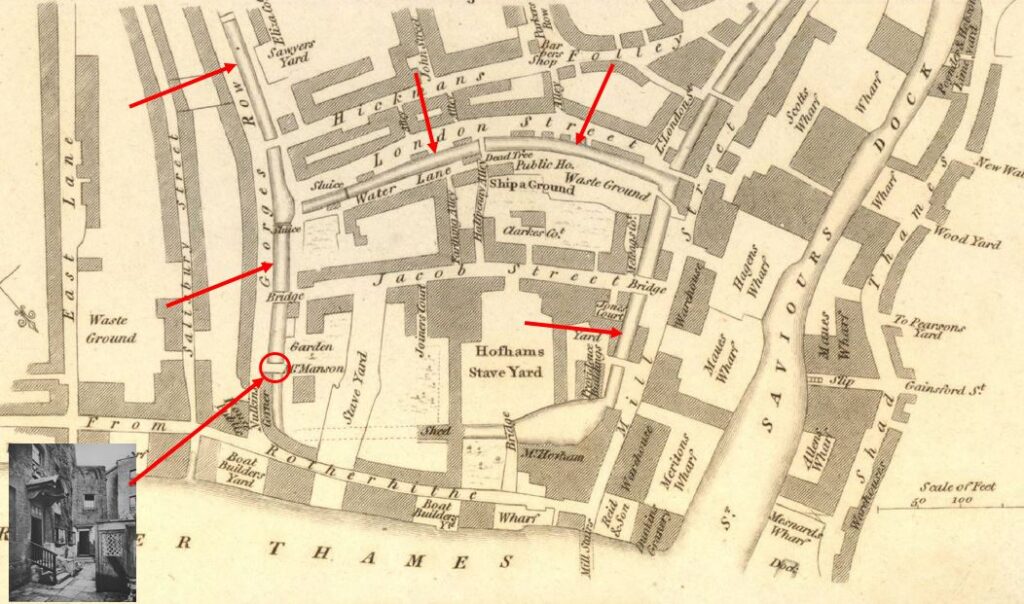

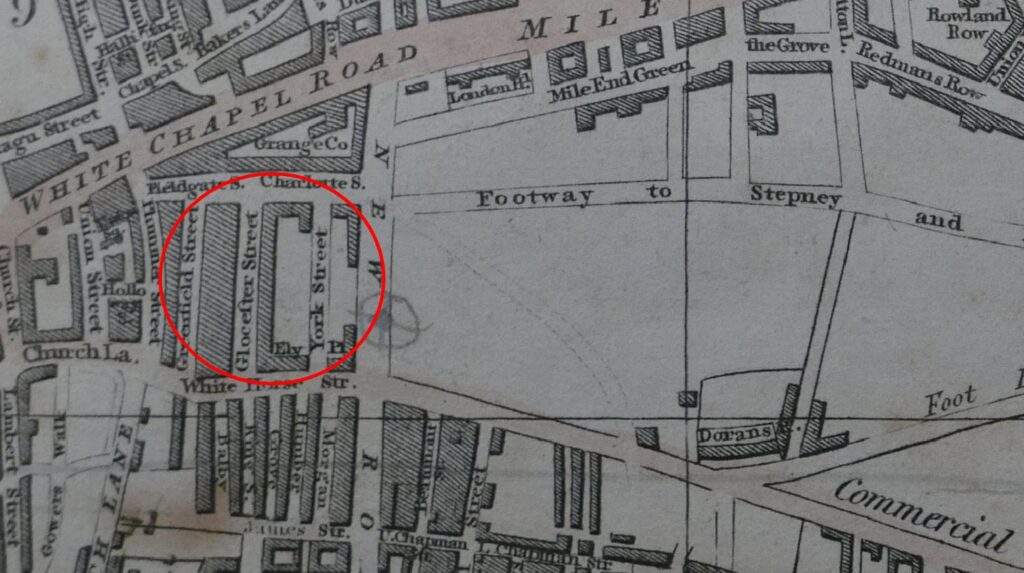

The report of the Great Fire in Cripplegate, and the photos which follow, mention lots of streets affected by the fire. Streets that had stood for centuries, but were lost under the Barbican development. I have plotted these streets in the following map, and marked the location of Waller and Brown’s building, the start of the fire, with a dark blue circle (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The fire brigade were quickly onsite, with the nearest station being in Whitecross Street (which was just to the right of Redcross Street in the above map).

The fire spread very quickly as most of the buildings were warehouses full of highly inflammable goods, and the account of the fire describes warehouses being burnt to the ground very quickly.

The following photo shows the view from the top of the ruins in Jewin Crescent, looking towards the tower of St Giles Cripplegate:

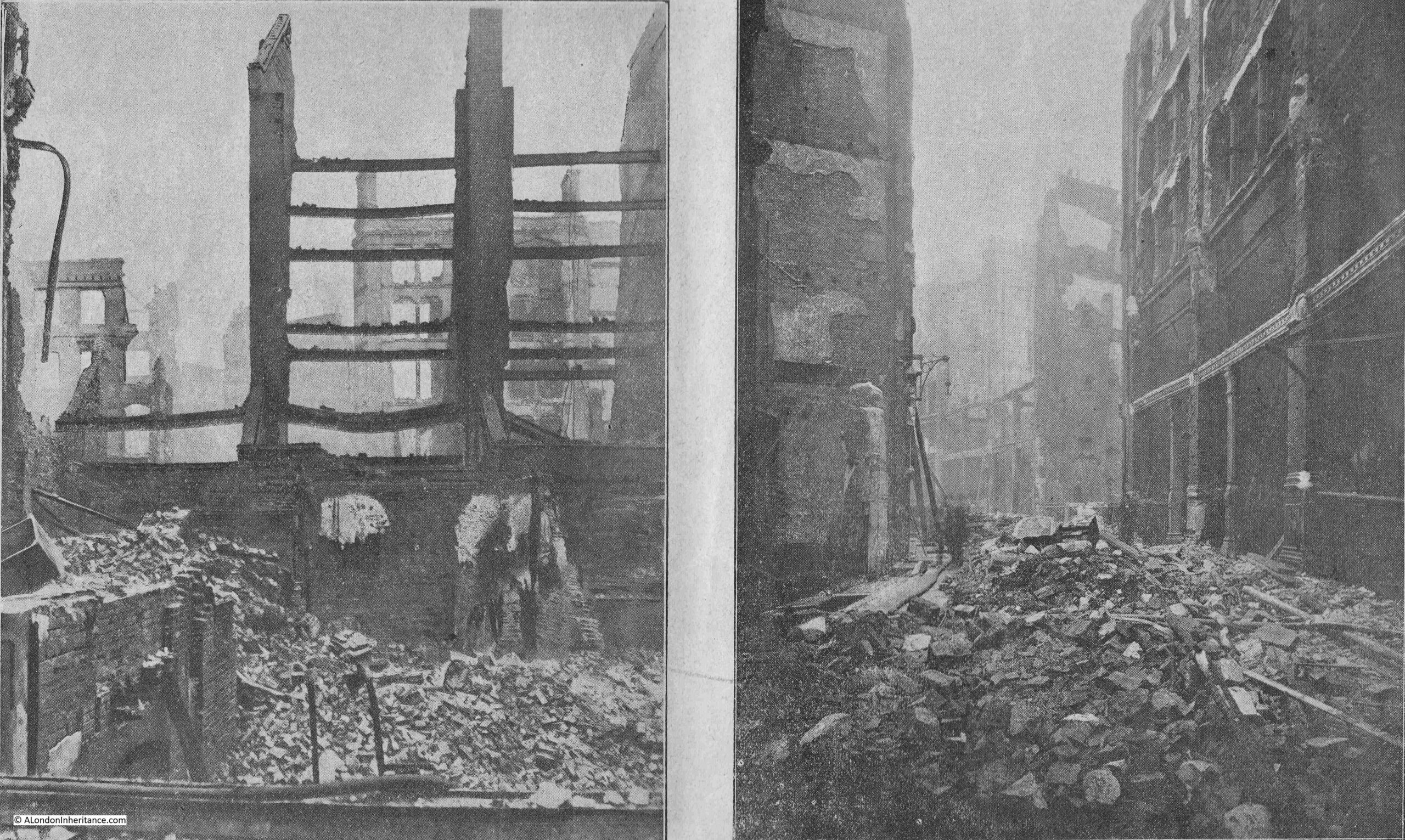

The following two photos are part of a two page spread which shows the devastated area between Hamsell Street and Well Street, looking south. Well Street to the left:

And Hamsell Street to the right:

Redcross Street seems to have formed a natural fire break. This was a major street in the area and one of the wider streets in Cripplegate unlike the rest of the streets that would be devastated by the fire.

The following photo was taken from the walkway underneath Gilbert House in the Barbican. Redcross Street ran left to right, from the corner of the building on the left (City of London School for Girls), across the water feature, and continuing underneath the buildings on the right. The fire started a short distance along the City of London School for Girls.

The following two photos show the destruction along Jewin Crescent.

Jewin Crescent started at where the City of London School for Girls in now located, ran along what is now the Thomas Moore Residents Garden, and rejoined Jewin Street under what is now Thomas Moore House (see map earlier in the post).

The following photo is looking across the residents garden, where Jewin Crescent occupied much of the space.

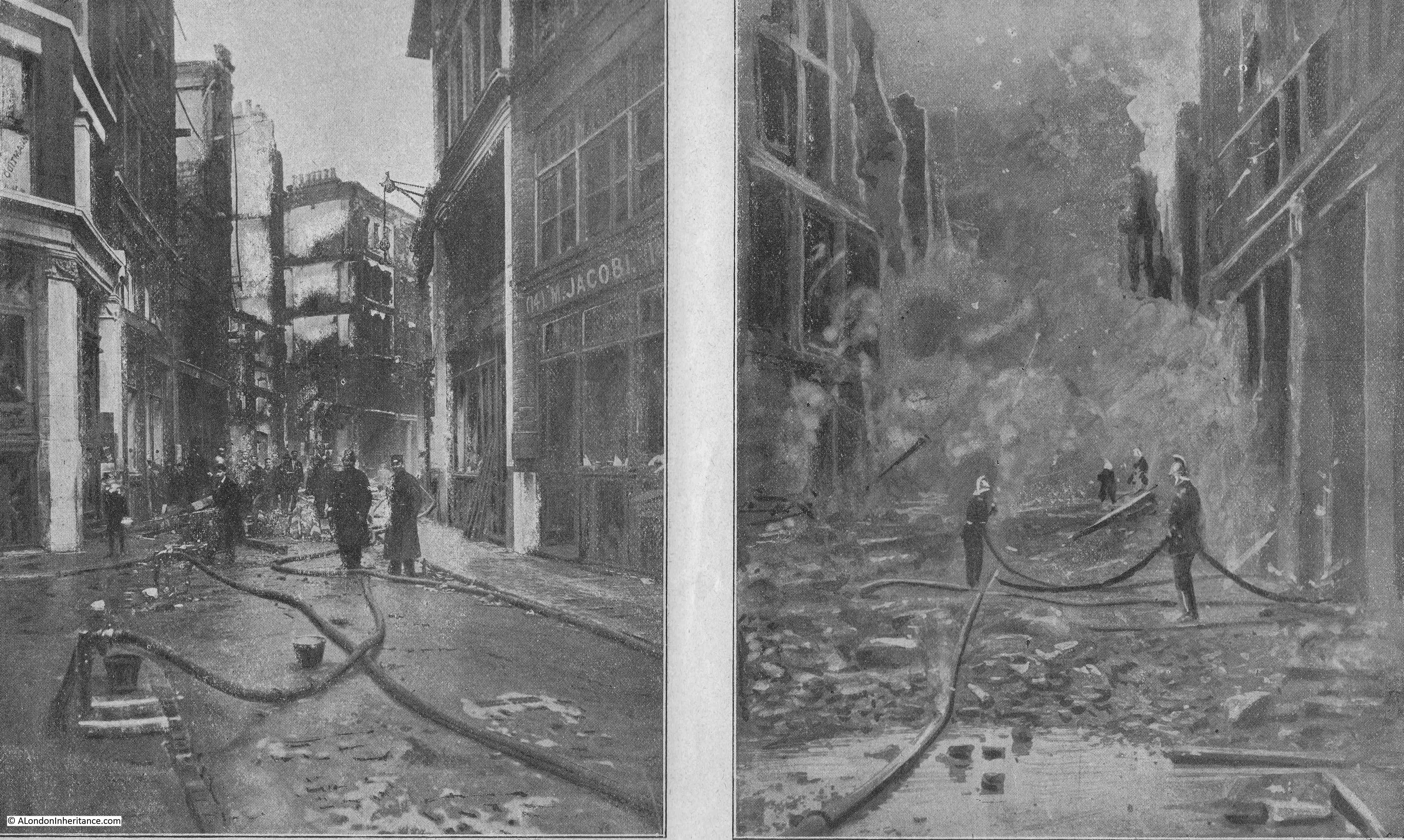

As the fire occurred during the early afternoon of a working day, there were very many people in the area and large crowds soon gathered which were a problem for the firemen attempting to get to the streets on fire and at risk.

Police and firemen tried to keep the crowd in order, but with difficulties. The report states that this was much easier in Redcross Street due to the large number of showers of burning embers that would blow across the streets. There were several cases of people in the crowd being badly burned by these, and that “many had damaged headgear”.

By the end of the day, police were being brought in from all across the City, and by the evening there were estimated to be a combined force of 500 firemen and police officers both fighting the fire and managing the crowds.

There were complaints about delays in getting sufficient fire appliances to the scene, however the first two appliances arrived just after one in the afternoon, only minutes after the alarm had been raised, four more arrived eight minutes later and within 30 minutes there were 19 steamers (steam driven pumps) at the scene of the fire.

The following photo on the left is looking down Well Street from Jewin Street . A bit hard to see, but on the left edge of the photo there is a sign for “Cup of Tea 2d”. This was the site of the Cripplegate Restaurant at number 12 Well Street. The building on the right of the left hand photo is that of the Bespoke Tailoring Company.

The above photo on the right shows the corner of Well Street and was occupied by London Hanover Stationers, as well as the Bespoke Tailoring Company – again, all buildings which would have had large quantities of inflammable materials.

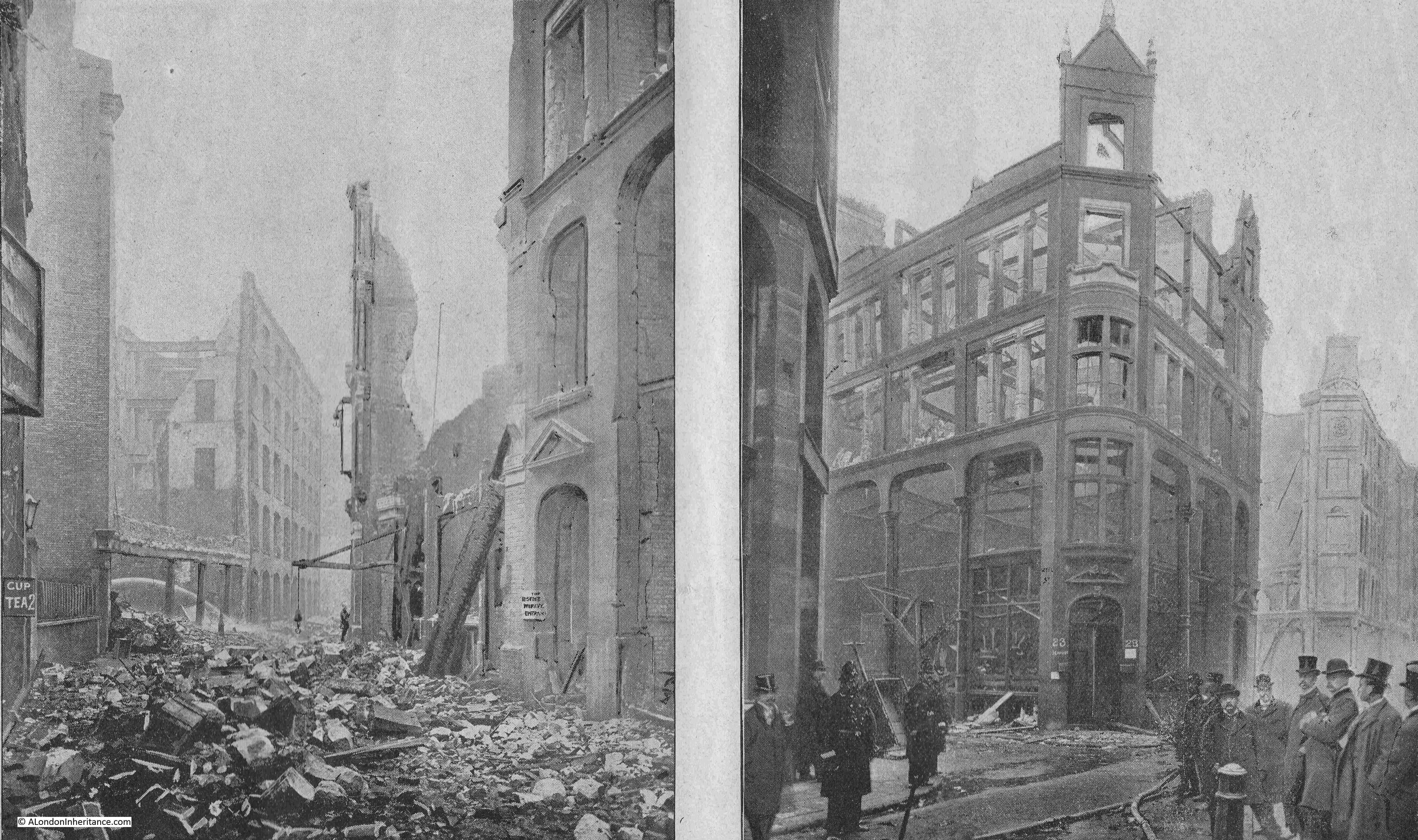

The photo on the left in the following pair was taken from the western end of Jewin Crescent looking east. This was the edge of the devastated area. The building on the right of the left hand photo was that of Mr. M. Jacob, importer of straw goods. the building suffered considerable damage and again highlights that the area was one in which a small fire could spread very quickly due to the large amount of flammable materials.

The photo on the right was taken on the Sunday after the fire and shows firemen continuing to damp down the ruins, with clouds of smoke and steam still rising.

The report into the fire mentions that the astonishing rate at which the fire spread was due to “the nature of the buildings, the stock they contained, the distribution of enclosed courts, numerous communications in party walls and the narrowness and relative positions of the thoroughfares”.

So although many of the buildings appear separate, with a wall between the neighbouring building, many walls between buildings had been knocked through, allowing the fire to spread without the firebreak of brick walls between buildings. There were also holes in the floors between floors, these were called well holes, and allowed the movement of materials between floors,

The following two photos are looking along Jewin Street. The photo on the left looking towards Aldersgate Street, and on the right, looking east from Aldersgate Street.

In the photo on the left, the ruins of the Grapes Tavern can be seen on the left, and on the right of the left-hand photo are the premises of A. Bromet & Co, wholesale jewelers and C.W. Faulkner & Co. Publishers and Colour Printers.

The buildings in the right-hand photo were occupied by agents, who specialised in the import and export of goods, provision of raw materials to the businesses in the area, along with the sale of finished goods.

The following photo is the view across Well Street to Jewin Street, and looks similar to many of the photos of wartime damage in the same area. The photo was taken shortly after the fire, when many of the buildings had been demolished due to the dangerous state in which the fire left them.

The following photo is looking west from near the tower of St Giles church. Jewin Street ran from the left, then under Thomas Moore House which is the building on the left. Well Street ran right to left, from Jewin Street, roughly at the end of the paved floor in the lower part of the photo:

The following photo shows the corner of Hamsell and Jewin Streets and shows a closer view of the Grapes Tavern on the ground floor of the corner building.

The Grapes Tavern seems to have dated from the early 19th century. The first mention of the pub I can find dates from 1818 when it was called the Bunch of Grapes. It appears to have been rebuilt after the fire, and was finally lost when the area was bombed at the end of 1940.

The following photo from the report was titled “The Ruins of Hamsell Street”, and mentions that the remains of the lamp-post on the right was opposite the warehouse of Beardsworth and Cryer, manufacturers, which was totally burnt out, again a photo that looks as if it was of the bombed City.

In the right hand photo of the following pair, the name Soley refers to Mr. George Soley who was a fancy box manufacturer:

The photo on the left of the above pair was taken from St Giles Churchyard and is looking west. on the left is the medieval bastion that can still be seen today.

In the following photo, the bastion can be seen on the left. St Giles Church is on the right, and the old churchyard once surrounded the church, went beyond the bastion then ran onwards to the left.

The following two photos make up a two page spread, showing the area of Hamsell and Well Streets, with St Giles in the centre of the photo (split across the two pages).

In the first photo, Hamsell Street is the street in the foreground. On the right of the photo is a lower building compared to the ruins of the others in the view. This was the rectory of St Giles Cripplegate, and stood on what is today the paved area to the west of the church tower (see photo of that view today, above).

The second part of the two page spread looking to the right of the church:

Remarkably, there were few casualties and no deaths from the Great Fire in Cripplegate.

Some workers had narrow escapes, including having to scramble over roofs to reach buildings that were not yet on fire. A few firemen were injured, included a burn from falling cinders, and being cut by glass.

The Times newspaper started an appeal for funds to help workers who had lost their jobs as a result of the fire. The paper commented that “the most grievous feature of the calamity will depend upon the numbers of industrious people who will be deprived of work at the commencement of the winter season, and many of whom, as being skilled in a special industry which for a time will be almost entirely suspended, will find it difficult or impossible to find work elsewhere.”

The “Star’s” reporting on Saturday 20th November 1897 was very typical of newspaper reports of the fire – The Greatest Fire of Modern Times, Damage Estimated By Millions:

The fire was of such significance that an inquest was held in the following weeks. The inquest was opened on the morning of Monday the 6th of December 1897 in the Old Council Chamber of the Guildhall.

A jury was assembled from the wards of Aldersgate, Farringdon Within and Cripplegate. The following photo shows the assembled jury, looking very much a late 19th century jury that you would expect.

The jury was asked to provide their view on 11 specific questions relating to the fire, and in order to help them make their decisions, a large number of people were called to provide evidence. This included the owner of the business in which the fire started, a number of members of staff working within the building, the architects of the building, the District Surveyor of the northern district of the City, Professor Boverton Redwood, an analytical and consulting chemist to the Corporation of London, and members of the Fire brigade and of the New River Company.

I have written about the New River Company in a number of previous posts, and it was their water supply through the streets of Cripplegate that was essential in being able to fight the fire. It was estimated that 15 million gallons of water was drawn from the mains of the New River Company by the Fire Brigade during the battle to control the fire.

The questions asked of the jury, and their verdicts are as follows:

- Where did the fire originate? – The fire originated on the first floor of No. 13 Well Street E.C. in the occupation of Messrs. Waller and Brown.

- At what time? – At from a quarter to one to ten minutes to one on Friday November 19th

- What was the cause of the fire? – The ignition of a stack of goods near the well-hole on the first floor (a well hole was a hole in the structure of the building between floors)

- Was it from spontaneous combustion? – No

- Was it from a gas explosion? – No

- Was it accidently fire? – No

- Was it wilfully fired, and if so, by whom? – Yes, by some person or persons unknown (This was decided by sixteen to six of the Jurymen)

- Was there any delay on the part of the Brigade in arriving at the scene of the disaster? – There was no delay after reception of the call

- Were the appliances and steamers and the coal and water supply sufficient? – With regard to the appliances at the fire, yes; as regards steamers at the fire, yes; as regards the coal, no; as regards the water, yes

- What was the cause of the rapid spread and development of the fire? – The style and construction of the buildings, the narrowness of the streets, the late call and the further delay of fourteen minutes from the time of receiving the call to the first steamer to work

- Have you any general suggestion or recommendation to make as to the reconstruction of the buildings destroyed? – We recommend that this area should be so reconstructed as to have greater regard to the safety of the adjacent property, and that all new buildings of the warehouse class, match-board lining should be prohibited for walls and ceilings and that all ceilings should be plastered and covered with fire-resisting materials

So the jury found that the fire had been started on purpose, but could not identify who had started the fire, although this was not the unanimous conclusion of the jury.

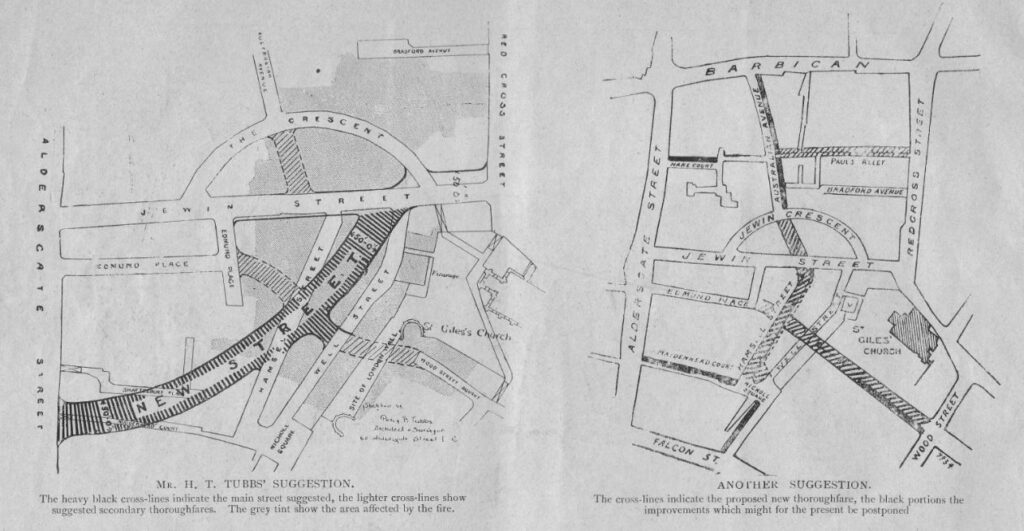

The report included a number of recommendations for how the area should be rebuilt after the devastation of the fire:

Recommendations included widening existing streets and building wider new streets. One recommendation included widening and extending Jewin Street all the way to Smithfield.

However in late 19th century London, the commercial imperative was key, and the area was rebuilt to the existing street plan, and again lined with warehouses and other commercial premises.

In a similar commercial vein, the City Press publication included several pages of adverts where advertisers made use of the fire to show the benefits of their products and services.

Dawney’s Fireproof Floors apparently withstood the tremendous fire and proved to be absolutely indestructible in a six storied druggist’s warehouse:

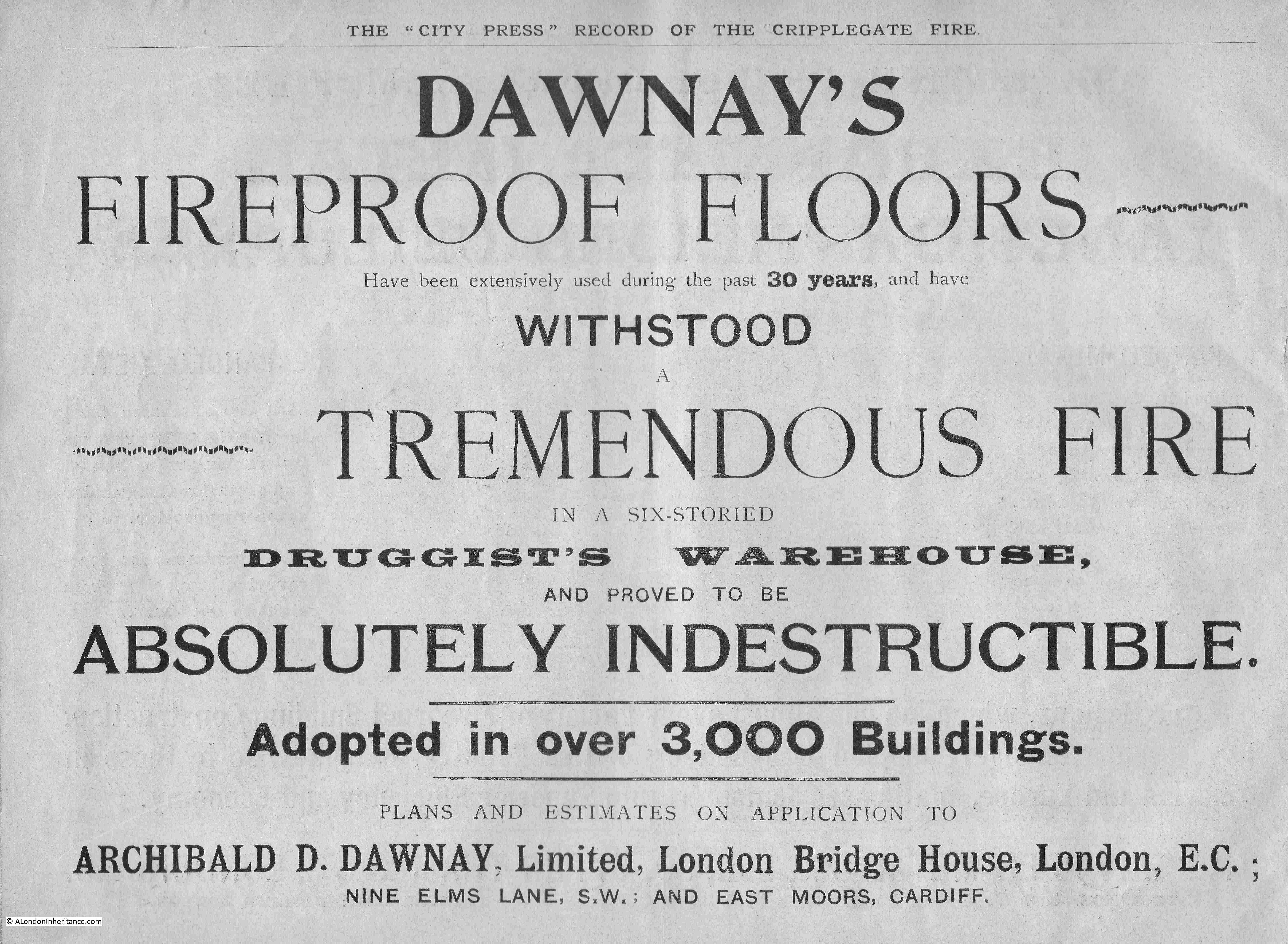

John Tann’s “Anchor-Reliance” Safes were again triumphant during the fire, and their advert included a couple of photos with their safes shown in the ruins of the buildings in which they were once housed.

If they are related, the Tann family seem to have had two seperate companies selling safes, with Robert Tann’s “Defiance” safes collecting some testimonials from the Great Fire.

The advert on the right in the above pair, and the following advert show the growing use of steel and expanded metal in the construction of buildings. There were no claims as to their products use in Clerkenwell, so these adverts were showing how buildings could be built to have prevent the spread of fire. The following Expanded metal Company also advertised the use of expanded metal as a tension bond in concrete.

Steel would become the dominant structural material in buildings over the coming decades and is used in all new City buildings today.

Another two companies looking to capitalise on the fire were the National Safe Deposit Company, who included a letter from Frederick Newton & Co who had lost their building in the fire, but were relieved that all their key documents were held by the National Safe Deposit Company, along with the Union Assurance Society who provided insurance for Fire and Life:

Another safe company – Ratner Safe Co. Ltd, who included a letter from Holyman & Co who had two Ratner Safes, which preserved all their papers during the fire. Mason & Co who had their “Steam Joinery Works” in Myddleton Street, Clerkenwell, were advertising “High-class joinery for the trade” and were ready for “every description of repair”.

More successful safes, a bucket fire-extinquisher, office fitters and a Fire Surveyor and Assessor Claims:

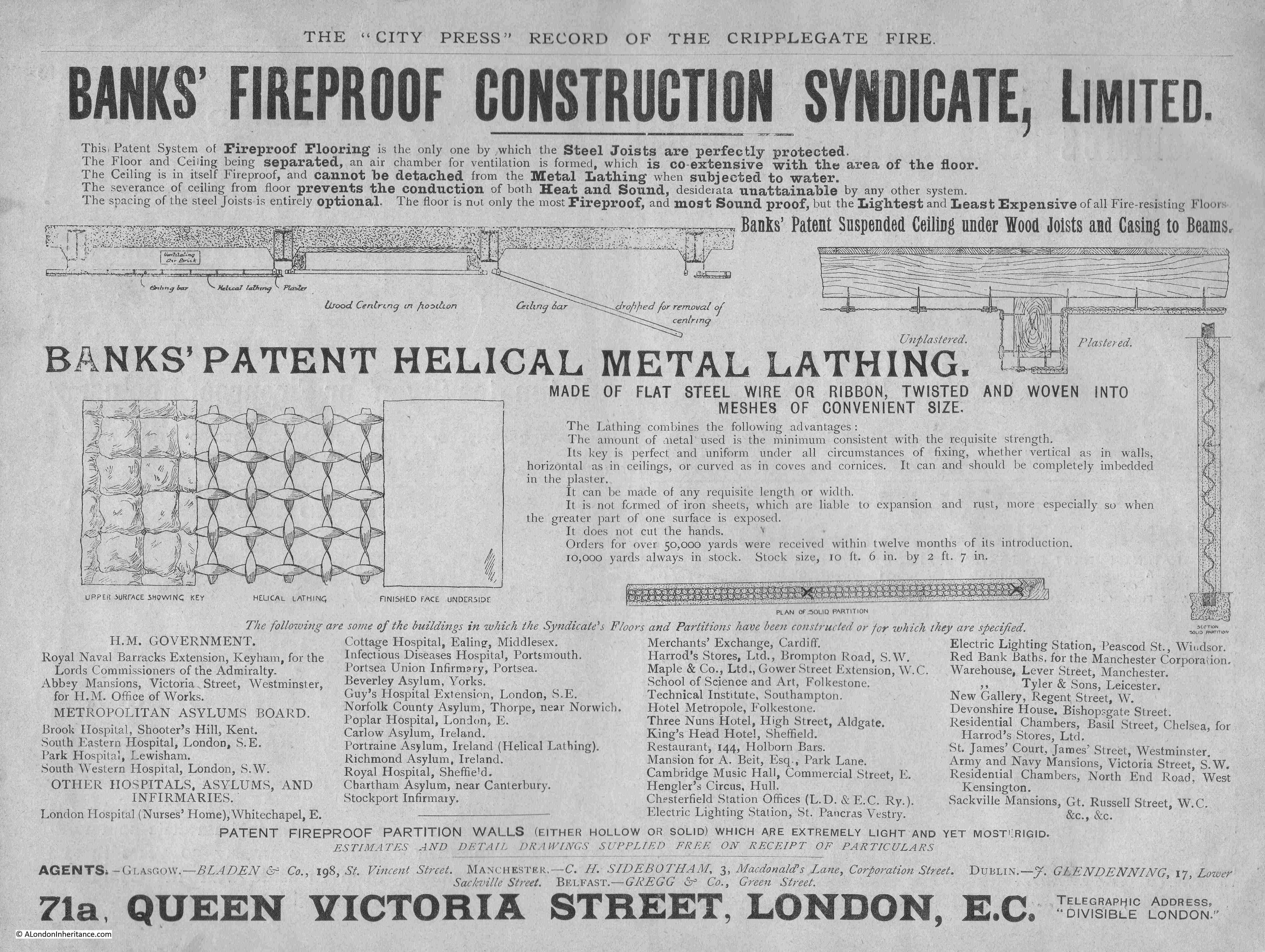

Another advert for the use of metal in construction, with fireproof flooring, the use of steel joists and “metal lathing” which was advertised for use in floors, ceiling and partitions:

The area of the Great Fire in Cripplegate was rebuilt quickly, with the new buildings continuing the commercial and industrial use at the time of the fire.

A new fire station was built soon after the Great Fire, in Redcross Street.

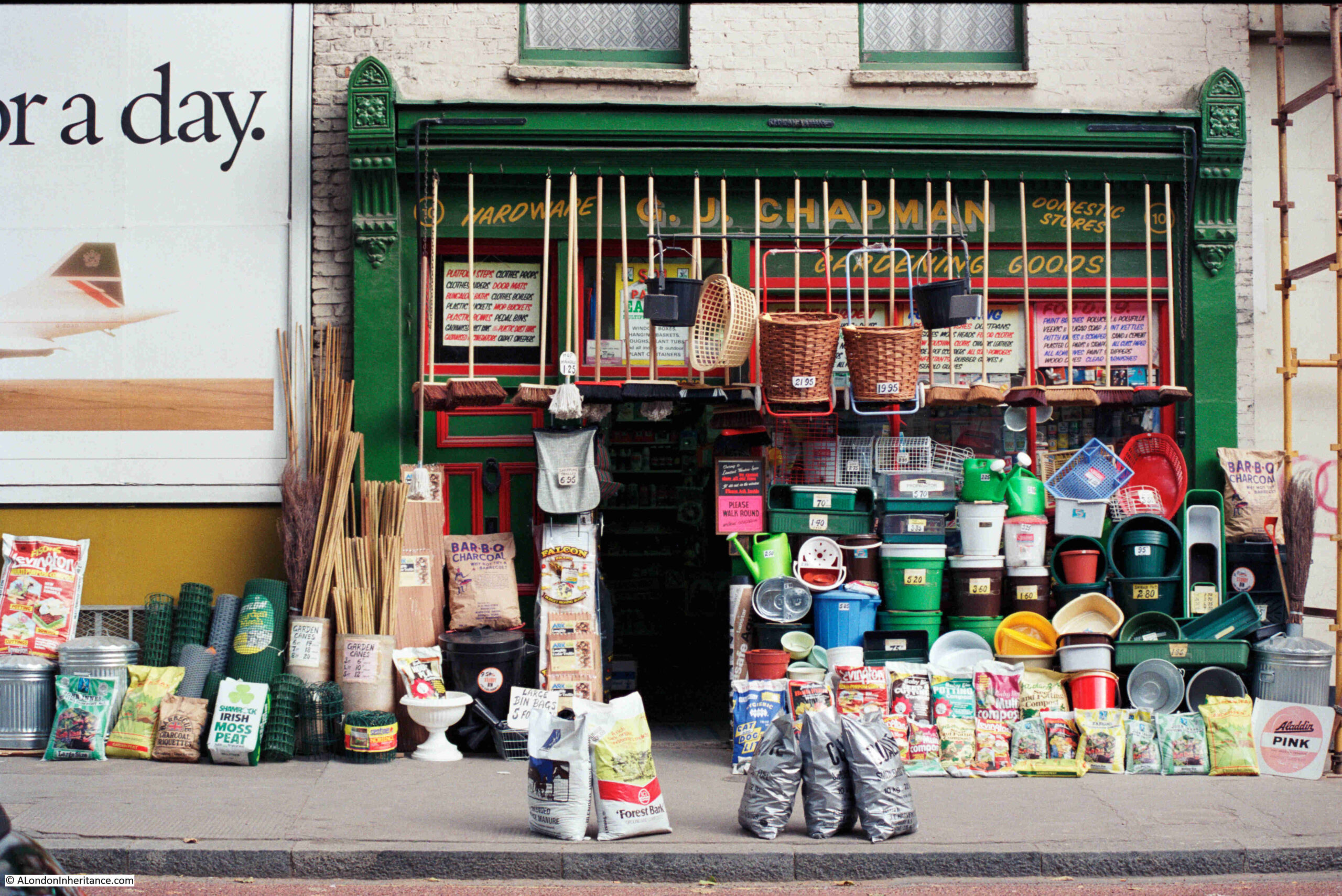

The justification for the new fire station in Redcross Street can be seen in this article from Lloyds Weekly Newspaper on the 4th of December 1898, which shows that the warehouses were full of the same type of materials as during the 1897 fire:

“Hitherto Watling-street has been the chief City fire station, and the proposed change would be of great advantage, as the warehouses in the vicinity of Wood-street are filled, as a rule, with the most combustible materials. On the northern side the station would be of very great utility to the over-crowded districts of St. Luke’s and Shoreditch, where most houses are old and the danger of fire considerable.”

In a little over 40 years after the Great Fire in Cripplegate, the area would be devastated again during one of the most damaging raids of the Second World War, when on the night of the 29th December 1940, fires created by incendiary bombs caused fires that would again lay waste to the warehouses and commercial buildings of Cripplegate.

The Barbican would be the post-war answer to “executive” housing in the City of London, and would erase the streets and street names of centuries.

I have written a number of posts, which include my father’s post war photos, covering the streets mentioned in this post, and the land occupied by the Barbican Estate. A selection of these posts: