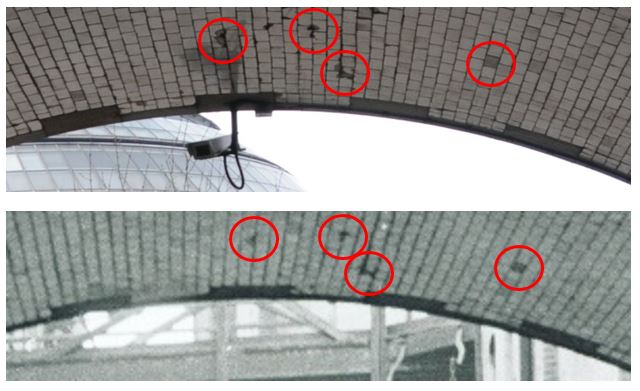

The subject of this week’s post is one of the earliest of my father’s photos as it dates from 1946. The negative is 75 years old and is not in that good a condition. The scanned image needed some processing to get it to the state you see below, and it is still rather grey with poor contrast.

The photo is from Cherry Garden Stairs, Bermondsey, looking along the river towards the City, with the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral visible through Tower Bridge.

The same view today, with the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in exactly the same place, however a very different river scene (the perspective looks different due to the very different camera and lens combinations used).

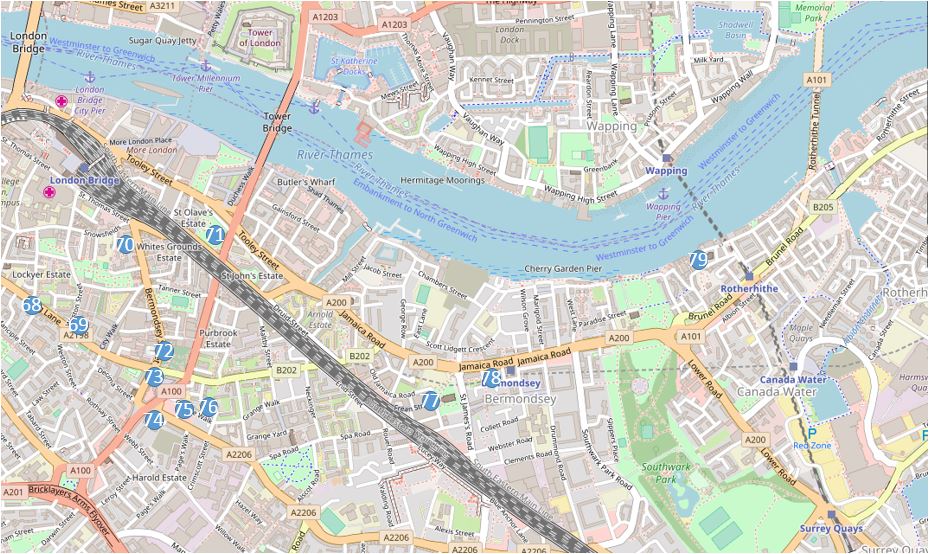

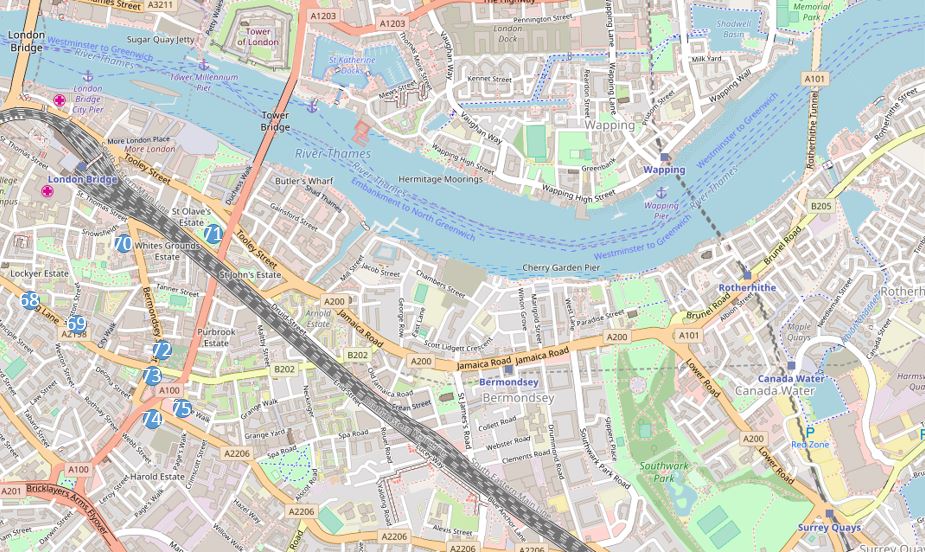

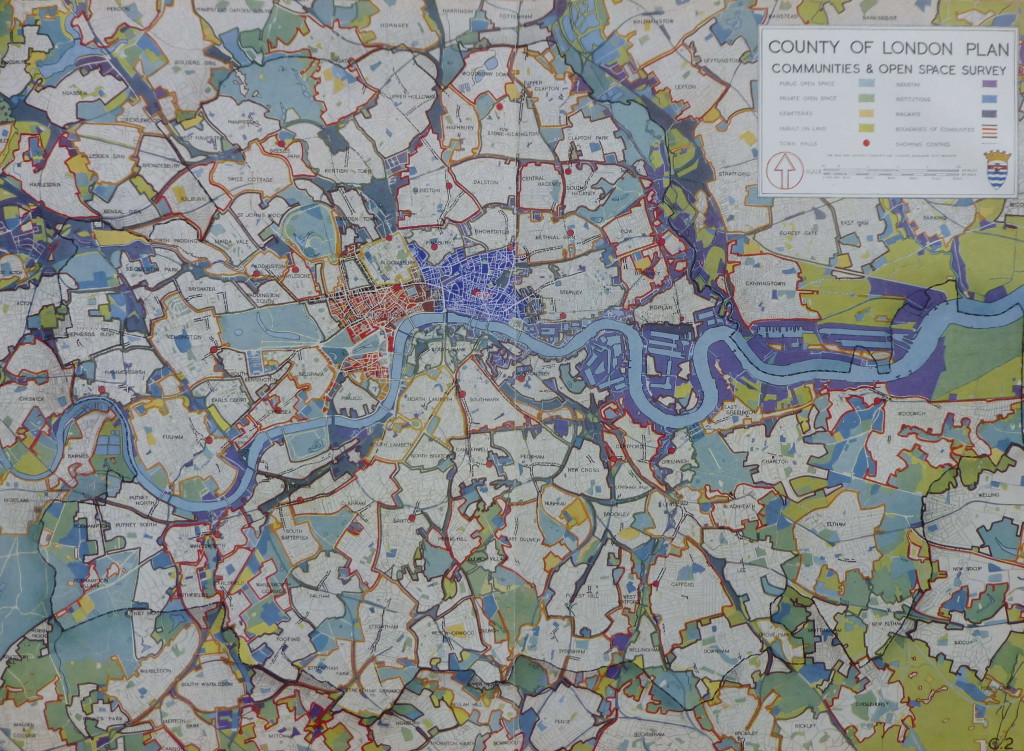

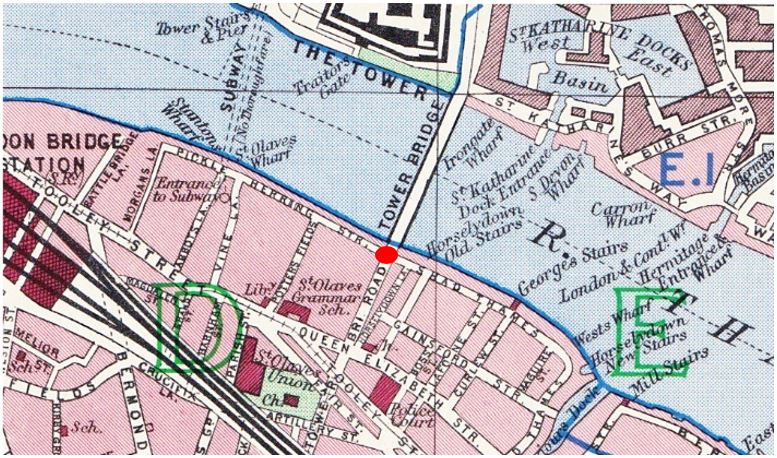

The location of Cherry Garden Stairs is shown in the following map, with the stairs located within the red circle at lower right. The 1946 photo looks along the southbank of the river towards Tower Bridge (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The two photos show a very different scene.

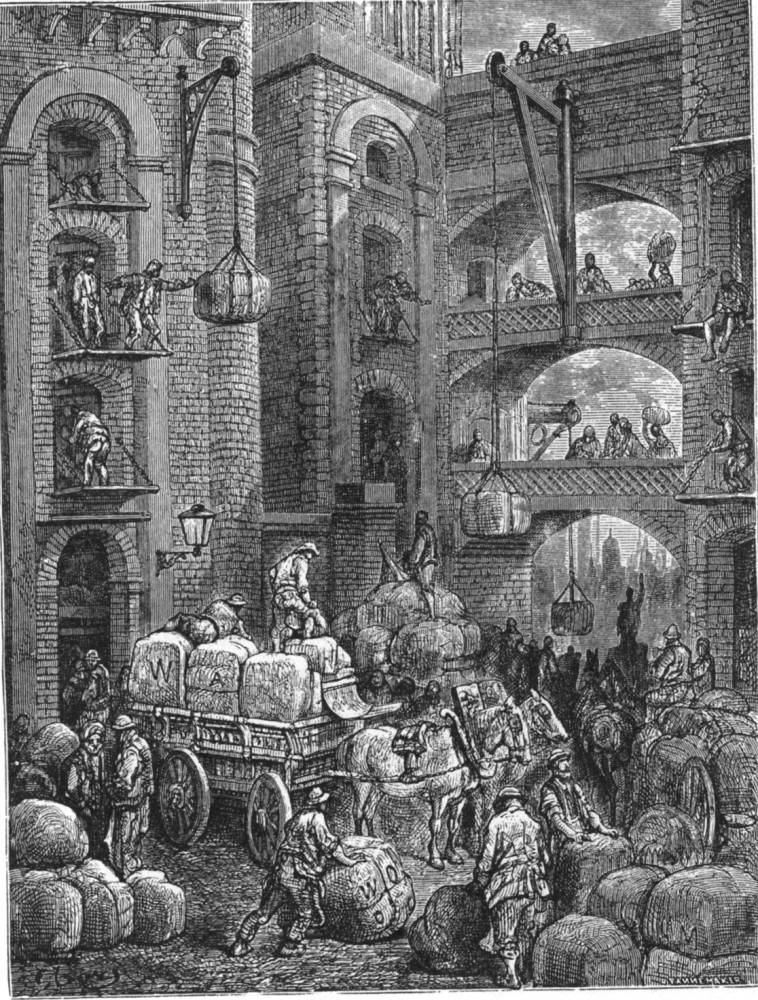

In 1946, the river bank was lined by warehouses, wharves and docks, with cranes along the river. A large number of lighters and barges are moored in the river, and directly in front of the camera, which would have been on the foreshore of the river.

In the 2021 photo the towers of the City are visible to the right, along with the Shard on the left. There are no more working warehouses, wharves or docks, and traffic on the river is today very different.

The river is though still used to transport construction equipment to a major construction site. In the 2021 there is a large shed on the left bank of the river, with the metal work of a travelling crane extending from the shed to over the river.

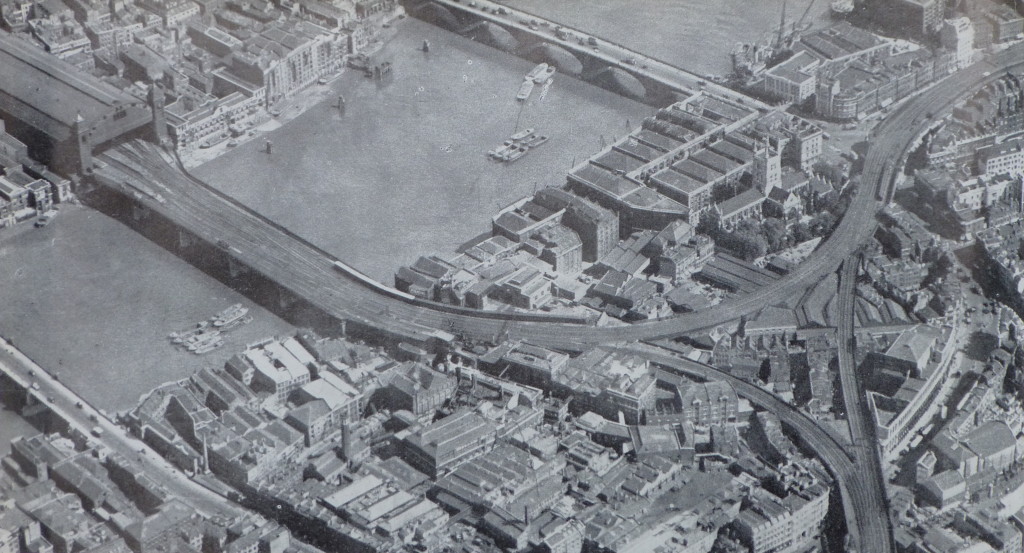

This is Chambers Wharf, one of the main construction sites for the Thames Tideway Tunnel. Chambers Wharf is one of the project’s main drive sites, with boring machines transported to the site via the river, and lowered by crane down to the point where the machines drive out, creating the tunnel.

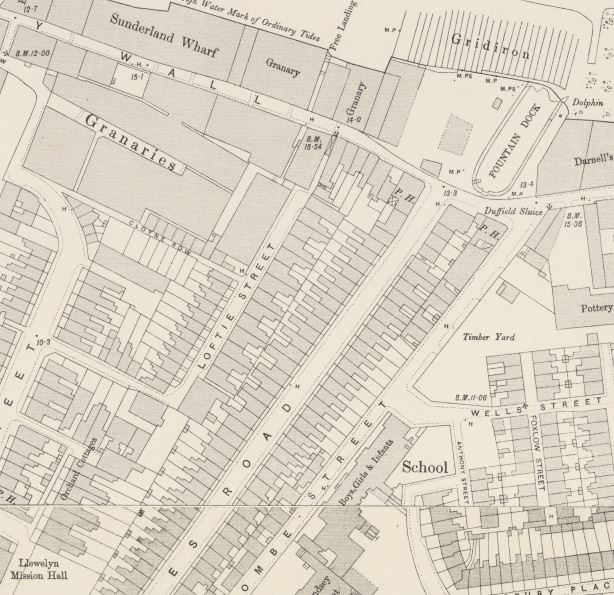

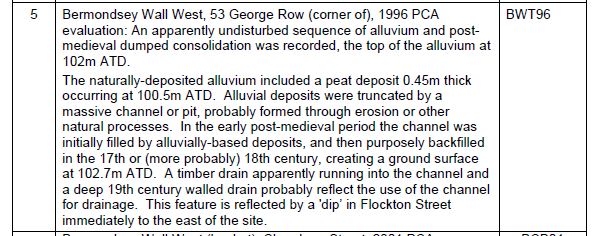

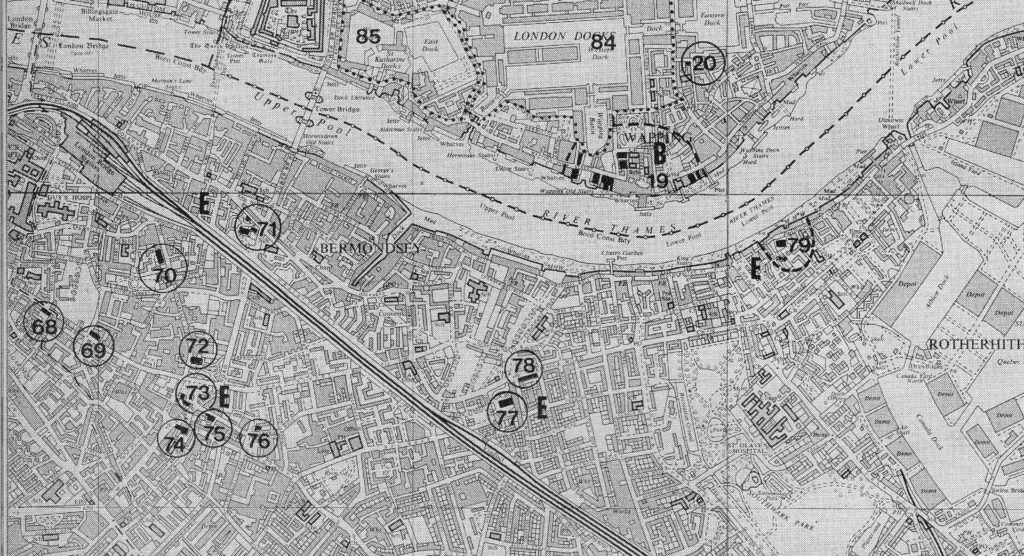

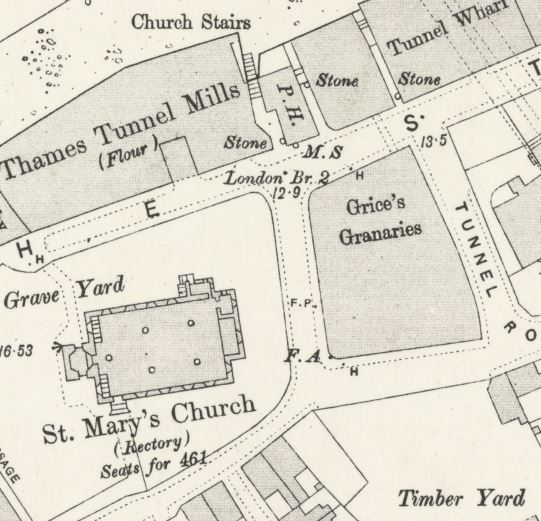

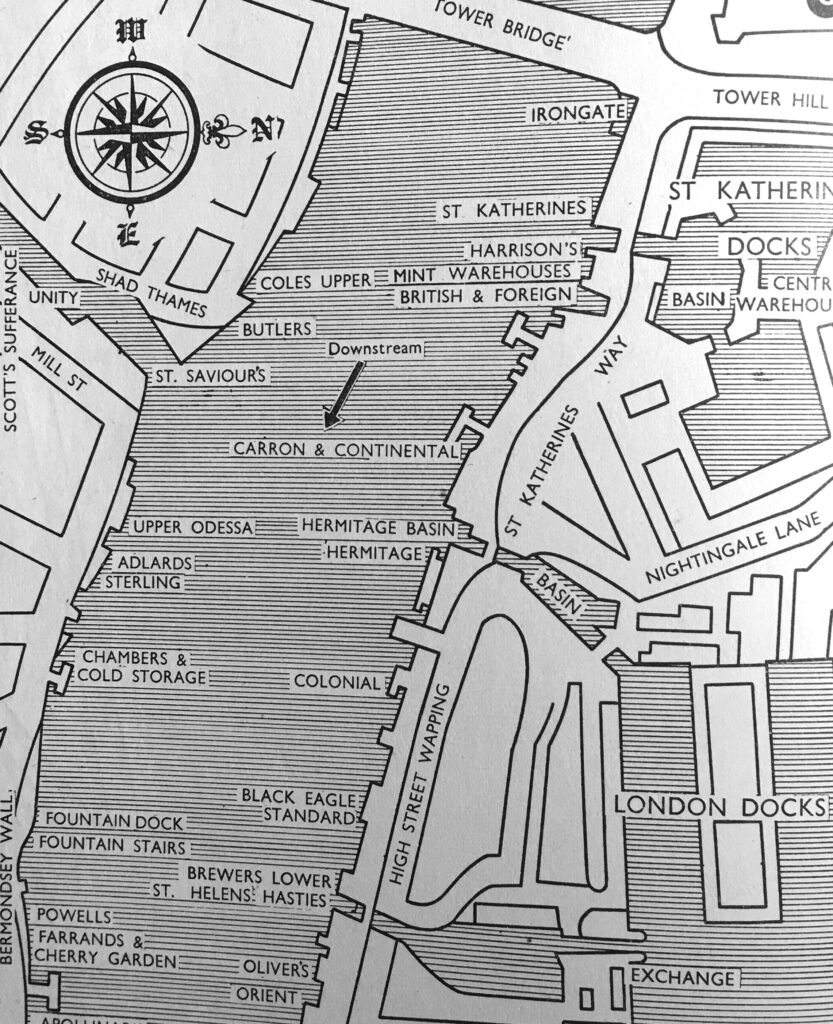

Chambers Wharf was one of the many wharves between Tower Bridge and Cherry Garden Stairs. The following map is from the 1953 edition of London Wharves and Docks, and the left of the river covers the area from Tower Bridge to Cherry Garden Stairs seen in my father’s photo.

The type of goods that these wharves dealt with are (from the top of the left bank of the river):

- Coles Upper Wharf: Bulk grain, flour, cereals

- Butler’s Wharf: Tea, rubber, colonial produce, bulk grain, fresh fruit

- Upper Odessa Wharf: Cereals, non-hazardous chemicals, bagged goods

- Adlards Wharf: General and bagged goods, timber

- Sterling Wharf: General, strawboards and wood pulp boards

- Chambers Wharf and Cold Storage: All types of food including highly perishable refrigerated dairy produce and quick frozen goods

- Fountain Dock: Grabable rough goods, coal, granite, ballast and sand

- Fountain Stairs Wharf: General, flour, cased goods

- Powells Wharf: Foodstuffs

- Farrands and Cherry Garden Wharf: General goods in bags, cases and casks, flour and corn starch

Also in the above map is St Saviour’s Dock, which I will save for a future post.

The list of wharfs does show the considerable range of goods that were being handled in the stretch of the south bank of the river shown in the 1946 photo.

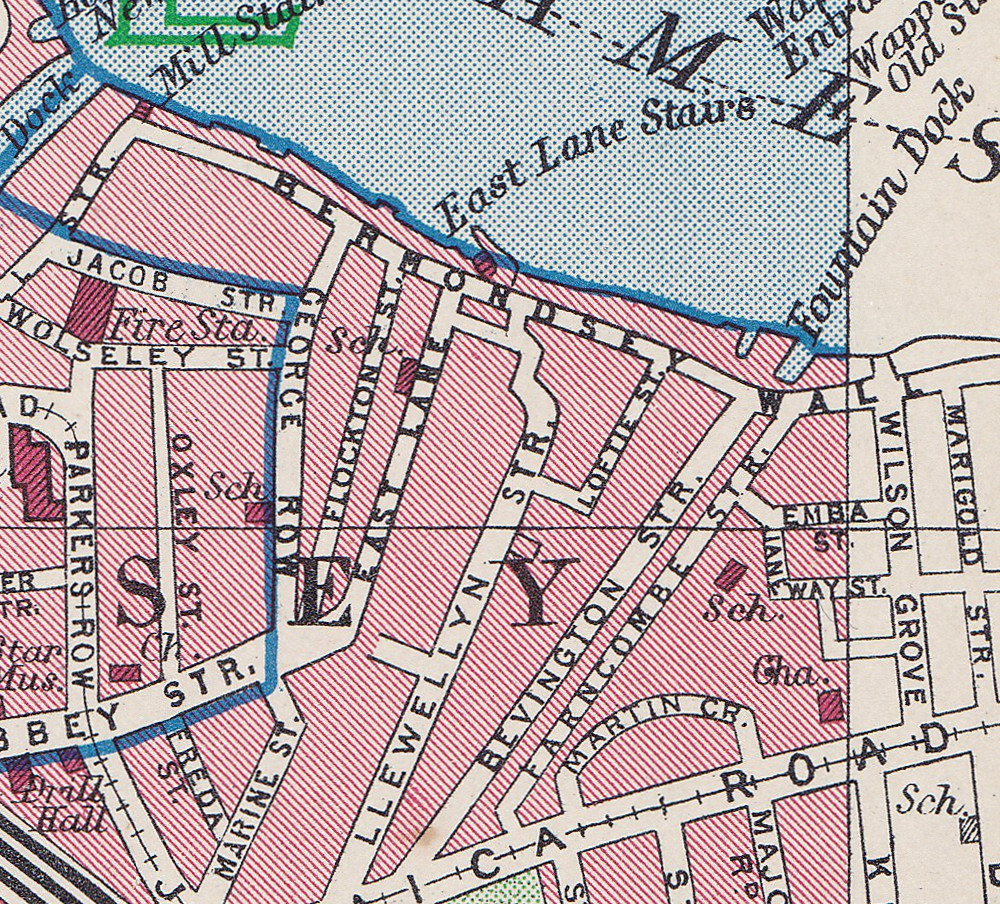

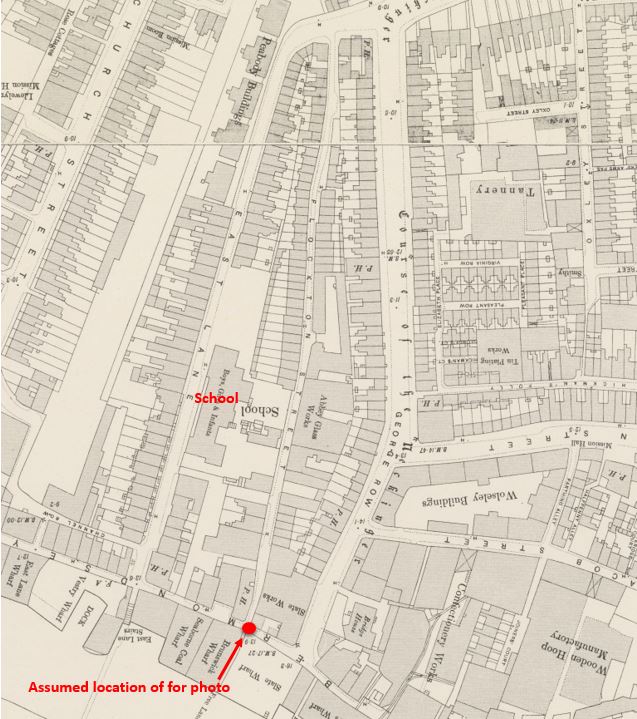

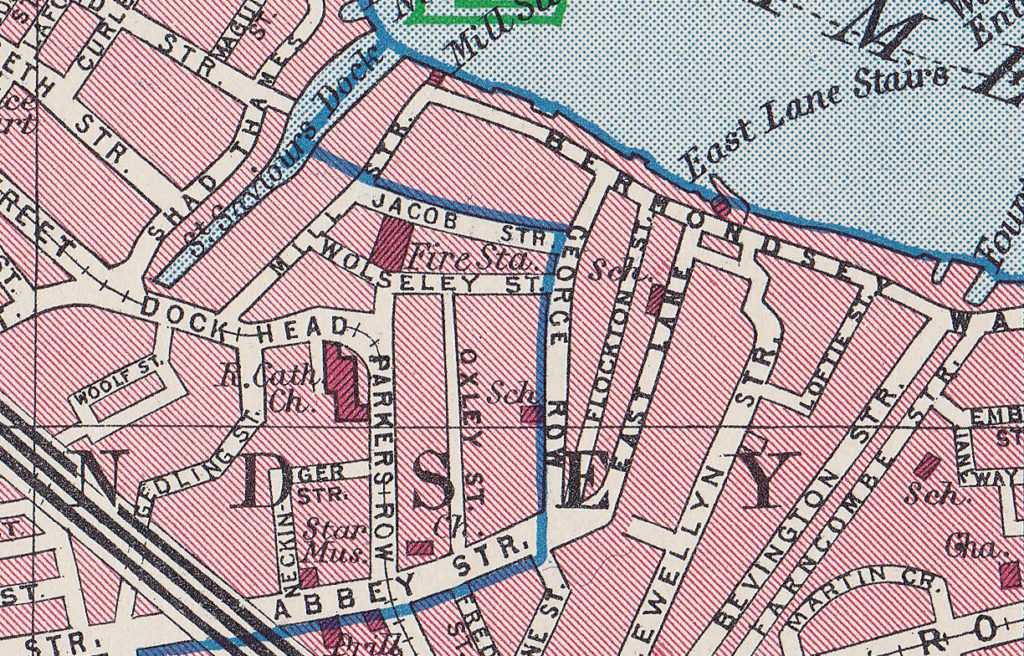

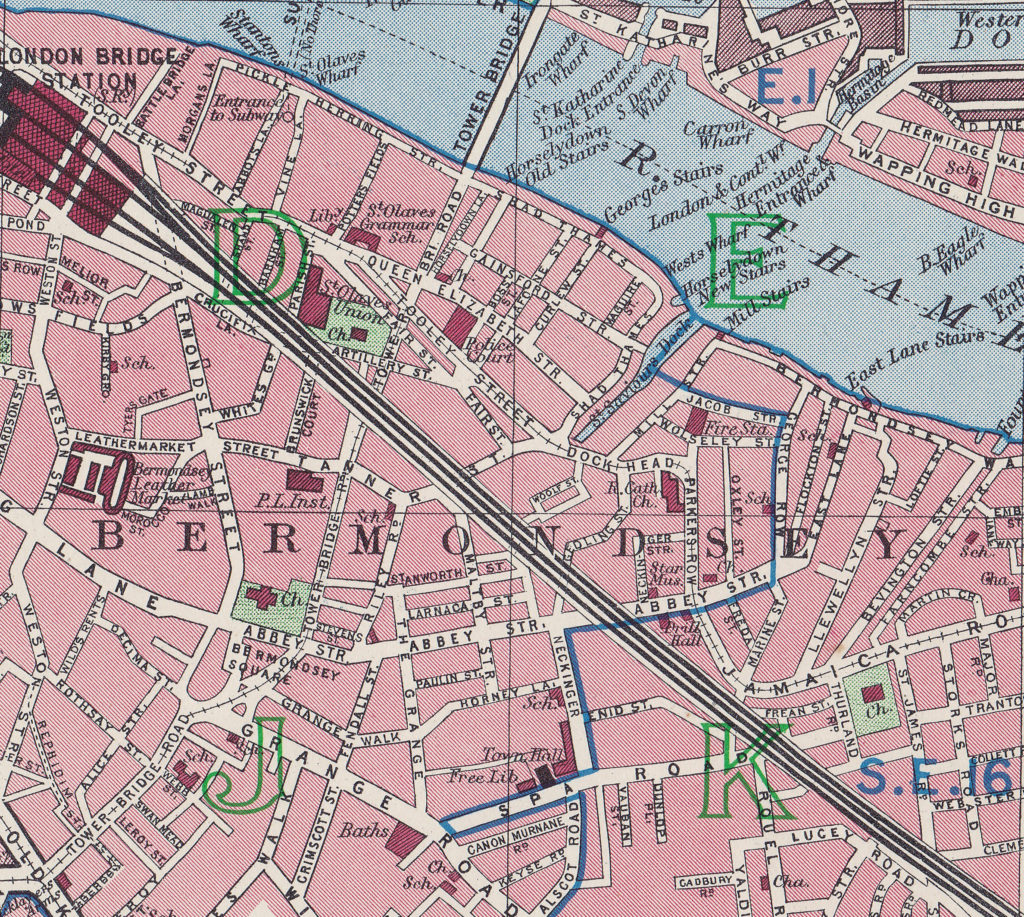

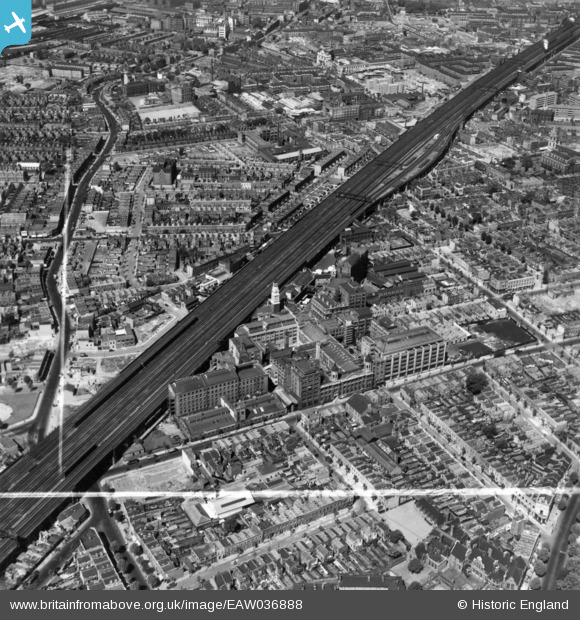

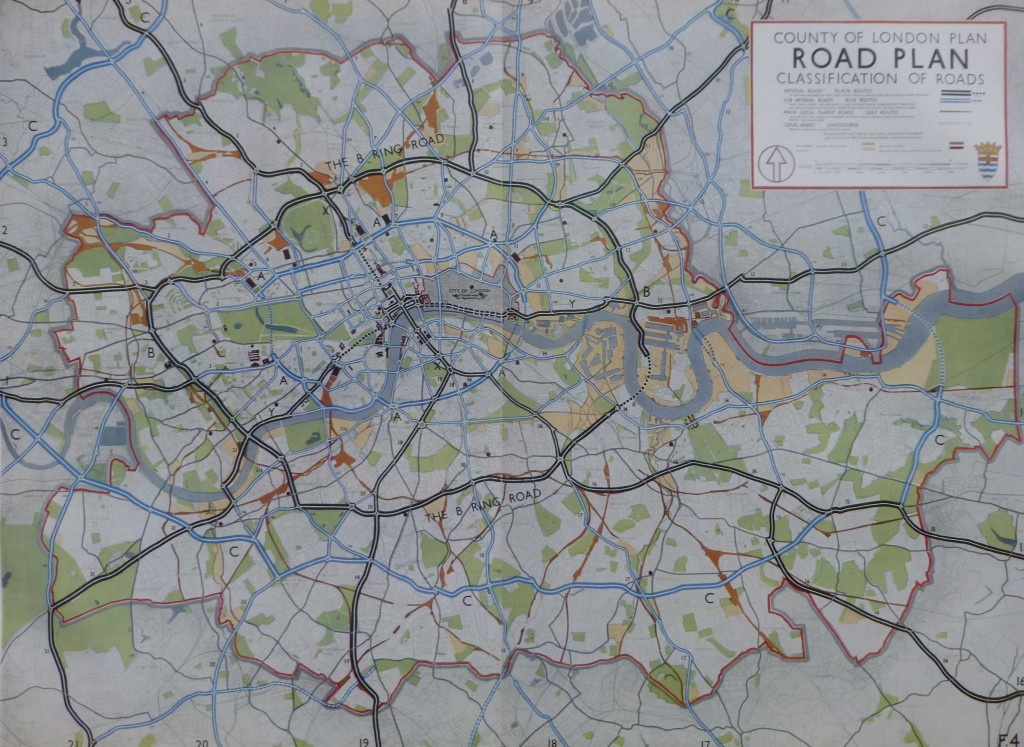

The following extract from the 1949 edition of the Ordnance Survey map shows Cherry Garden Street in the centre of the map, running up to Cherry Garden Stairs, which are at the lower left of Cherry Garden Pier (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

A pier at the site seems to date from the later half of the 19th century, and Cherry Garden Pier is still there today, although used by a private company with no public access.

One interesting point in the above map, is to the right of the map is the Millpond Estate, a 1930s housing development which can still be seen today. The location of the estate had been the site of a flour mill, mill pond and terrace housing. The mill pond was once part of an extensive irrigation system that ran inland to much larger ponds – lots more to discover around this part of Bermondsey.

Cherry Garden Stairs are one of the many old stairs that provided access to the river. The earliest newspaper reference I can find to the stairs dates from the 25th May 1738 when “Yesterday morning an eminent Shoemaker at Cherry Garden Stairs, Rotherhith, was found drowned in the River Thames”.

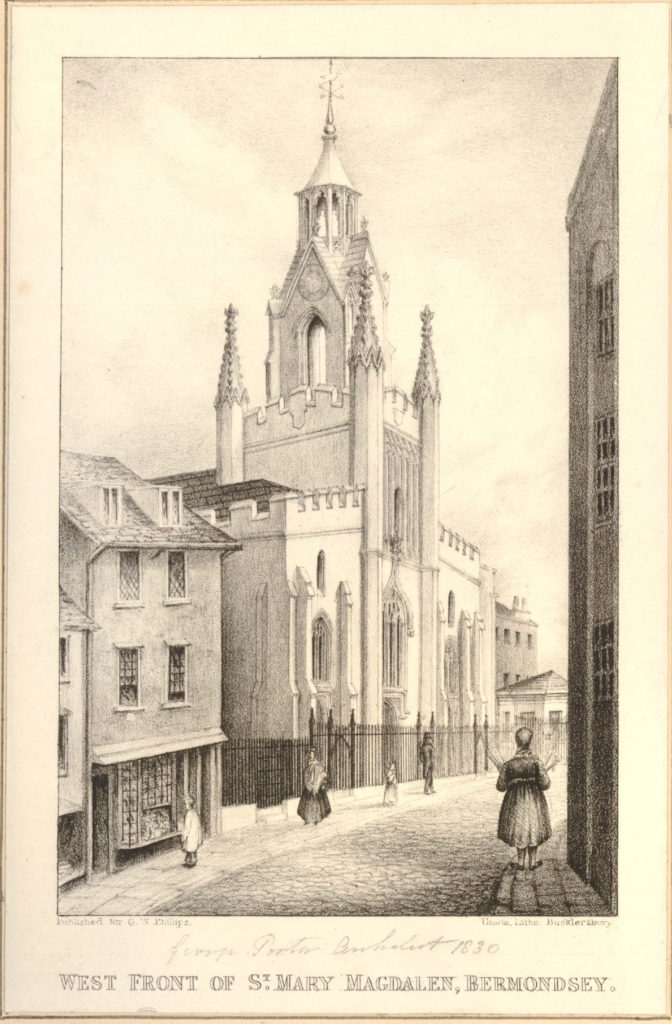

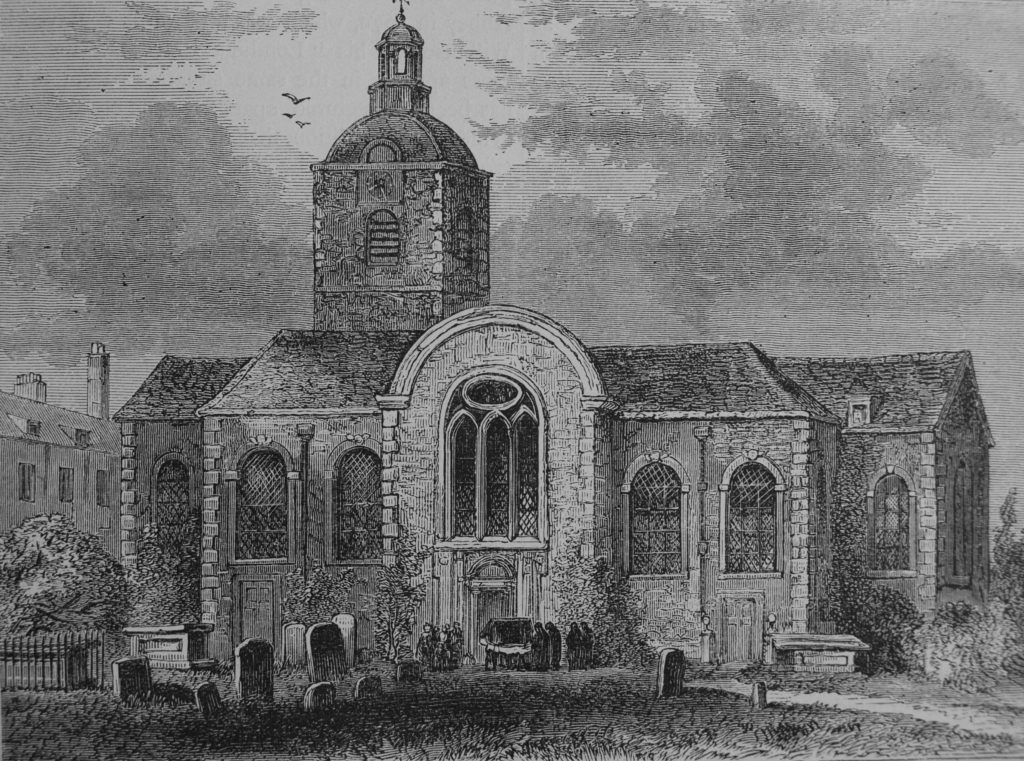

The stairs are probably much older than the 1738 reference. Leading back from the location of the stairs (see above map) is a street called Cherry Garden Street. The street is named after a pleasure garden that was here called Cherry Garden.

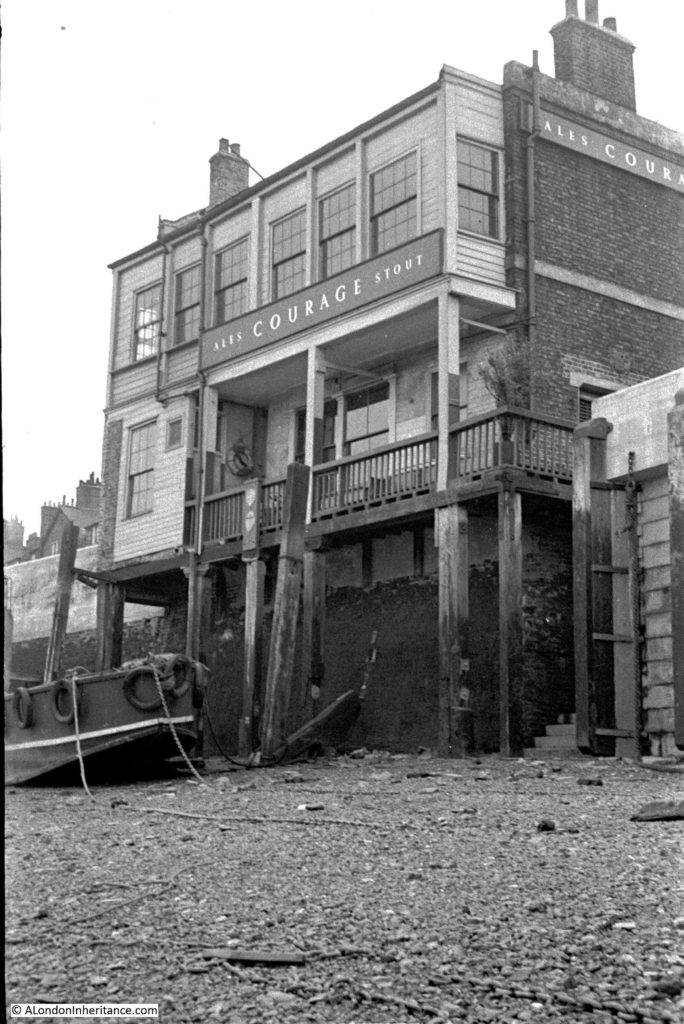

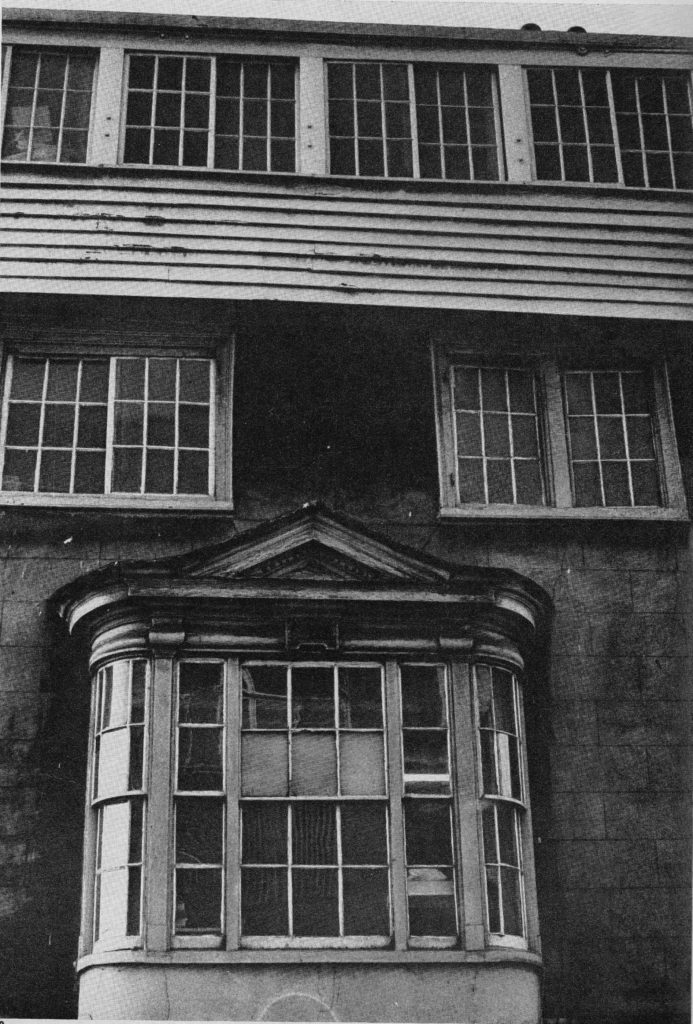

In volume four of the 1912 edition of the History of the County of Surrey in the Victoria County History series, there is reference to a Jacobean style house called Jamaica House which could still be found in Cherry Garden Street until 1860.

This house appears to have been part of the gardens as in the same volume, there is a quote from Pepys which reads “To Jamaica House, where I never was before, together with my wife, and the Mercers and our two maids, and there the girls did run wagers upon the bowling green: a pleasant day and spent but little”.

Jamaica House or Tavern in 1858 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Pepys visit is referenced in an article in the Westminster Gazette on the 7th October 1910, which also recalls an inn that was located by the stairs: “Cherry Garden-street, the scene of yesterday’s big riverside fire, occupies the site and preserves the name of the old Bermondsey ‘Cherry Garden’, once a well-known place of public resort. The Cherry Garden was favourably known to Pepys, who recorded his visit there in his famous diary. At Cherry Garden Stairs there was formerly a celebrated inn known as the Lion and Castle, a name supposed to have been derived from the marriage which took place between the Royal House of Stuart and that of Spain. Close by was the even more famous Jamaica, traditionally supposed to have been the residence of Cromwell”.

Edward Walford in Old and New London (1878) doubts the Lion and Castle name originating from a Stuart / Spanish name and prefers the source to be “the brand of Spanish arms on the sherry casks, and have been put up by the landlord to indicate the sale of genuine Spanish wines, such as sack, canary and mountain”.

The Lion and Castle pub seems to have been at Cherry Garden Stairs from the late 18th century to some point around the 1860s. It was not shown on the 1895 OS map.

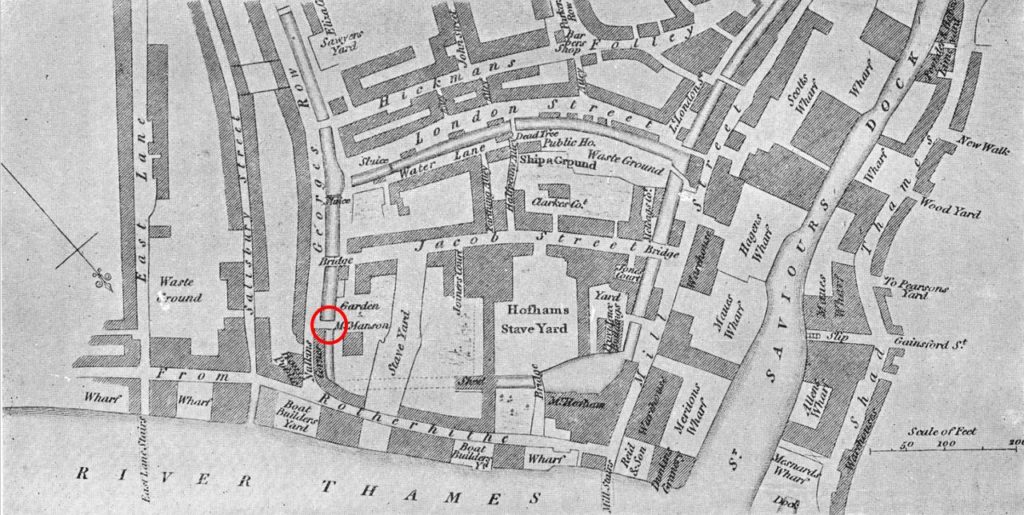

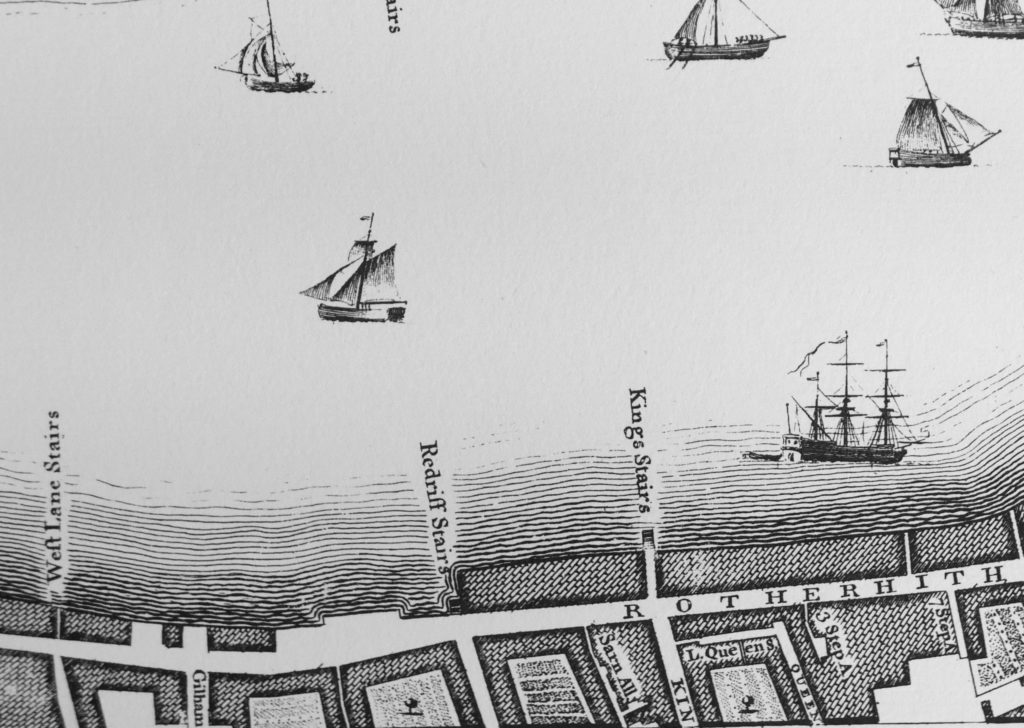

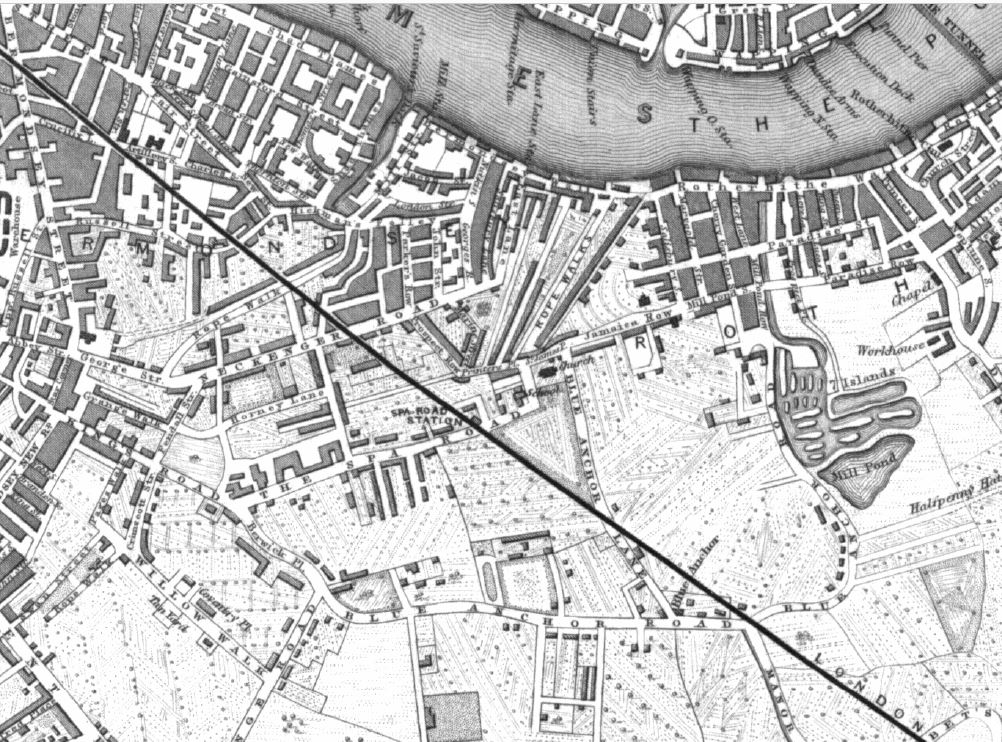

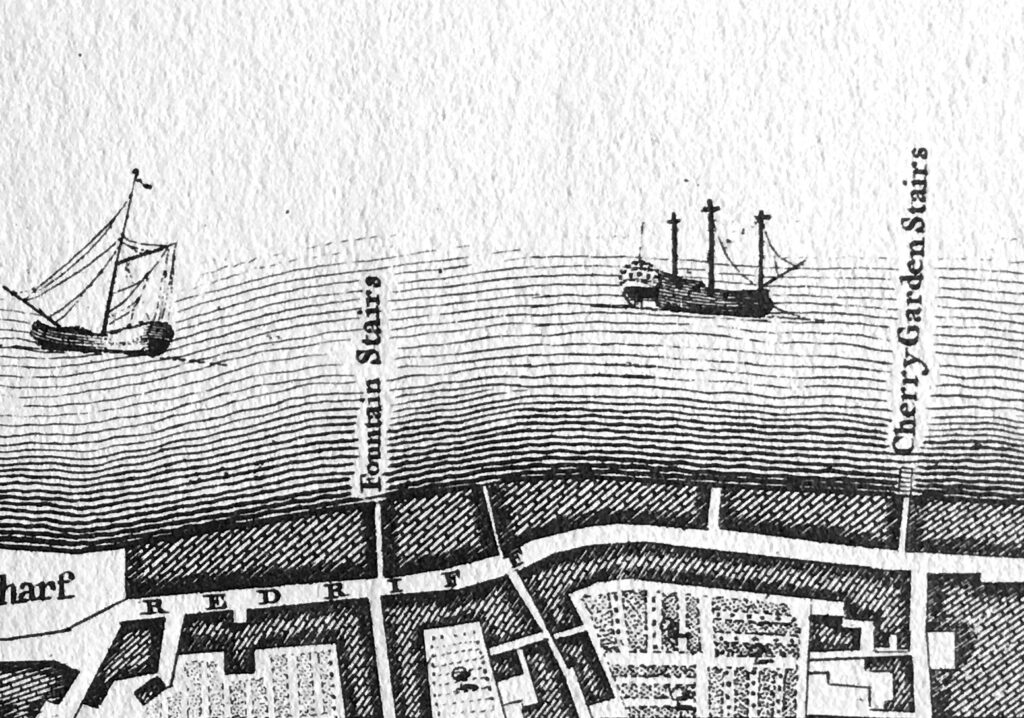

It may have been that the stairs were used for river access to the pleasure gardens and that was why they took the name of the gardens. Rocque’s map of London in 1746 shows Cherry Garden Stairs (right on the corner edge of my copy of the map):

Thames stairs were so very important for centuries in the life of the river, and for all those who had some connection with the activities carried out on, or alongside the Thames.

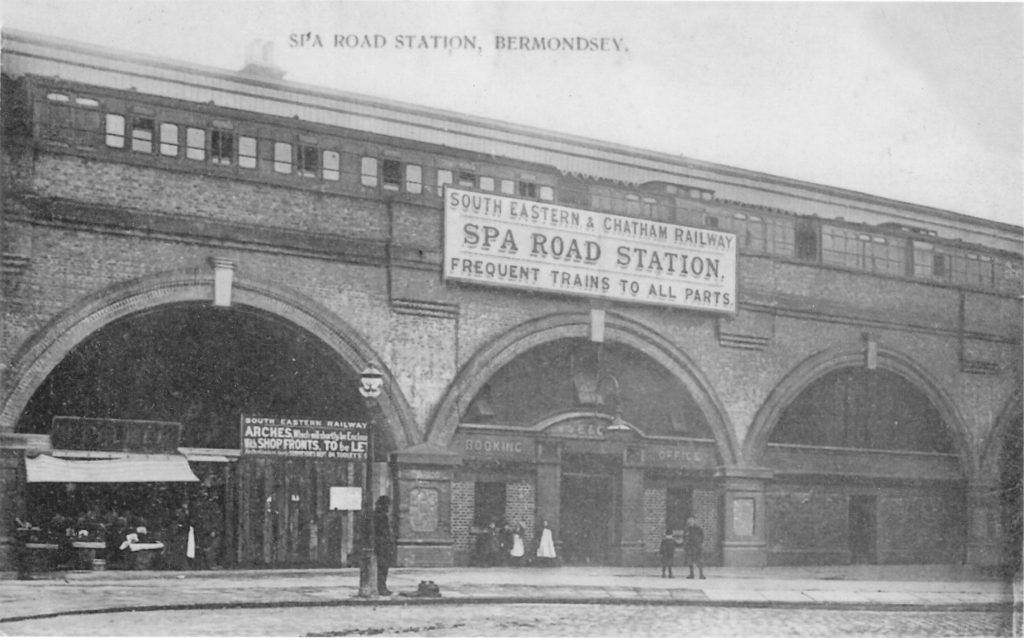

As well as providing access to and from the river, Thames stairs were a key landmark. There are hundreds of newspaper references to Cherry Garden Stairs during the 18th and 19th centuries. The majority of these are adverts of ships for sale, for lease, or that were about to set out and were advertising for cargo or passengers.

For example, the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser on the 8th May 1818 has the following advert: “Has only room for a few Tons of Goods, and will be dispatched immediately. For Gibraltar direct. The fine, fast-sailing Brig PRINCE REGENT, Henry Stammers, Commander. lying at Cherry Garden Stairs. burthen 118 tons. For Freight or Passage”.

Other reports concern accidents, collisions, drowning and bodies pulled from the river near the stairs. Such an incident is recorded in the last newspaper reference to the stairs that I can find, when on the 29th November 1936, Reynold’s Newspaper recorded that a ten year old Bermondsey boy had fallen into the Thames from Cherry Garden Stairs and had drowned.

Thames stairs and pubs also seem to be a magnet for crime. For example, there are reports of passengers being rowed across the Thames and then robbed in, or close by the pubs that were often located near the landside of the stairs.

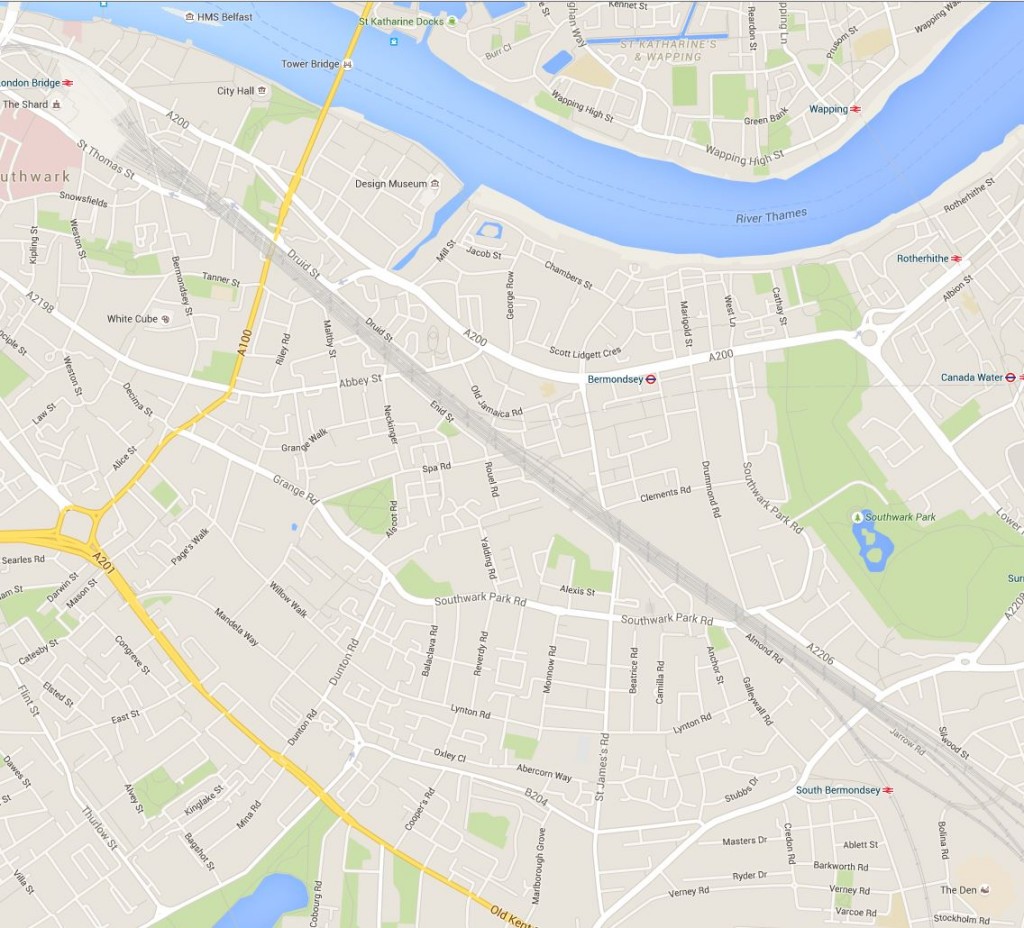

The tide was in when I arrived at Cherry Garden Stairs to taken the comparison photo. Access to the foreshore is now via a modern set of metal stairs that run over the embankment wall that was built as part of the walkway / tree lined open space that runs along the river. Difficult to photograph without being on the foreshore, but the stairs can be seen at the end of the wall in the following photo:

The walkway to the pier can be seen in the background.

I am sure that my father took the original photo from the 1946 version of the stairs, as it was by standing on the stairs that I could get the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in exactly the same position. At this distance from Tower Bridge and the cathedral, even a small change in position changed the orientation of bridge and dome.

There is much more to discover in this part of Bermondsey, so it is an area I will be returning to again.