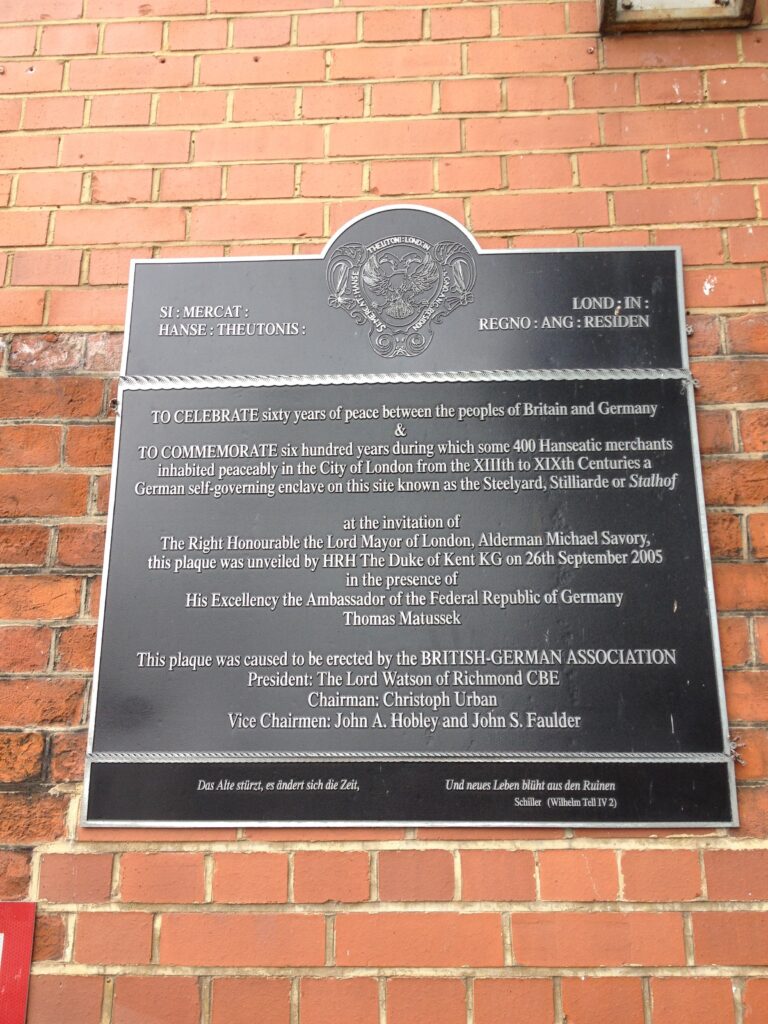

One of the pleasures of wandering around London streets are the random memorials and objects that have survived from previous centuries, and how they can lead to a fascinating story of an aspect of the City’s history. Perhaps one of the strangest can be found in Cloak Lane, to the west of Cannon Street Station, between Dowgate Hill and Queen Street.

The ground floor of one of the buildings on the northern side of Cloak Lane has a number of arches with metal railings, and a large memorial occupying one of the arches:

A closer view, and the railings have signs that imply that there is perhaps more to discover:

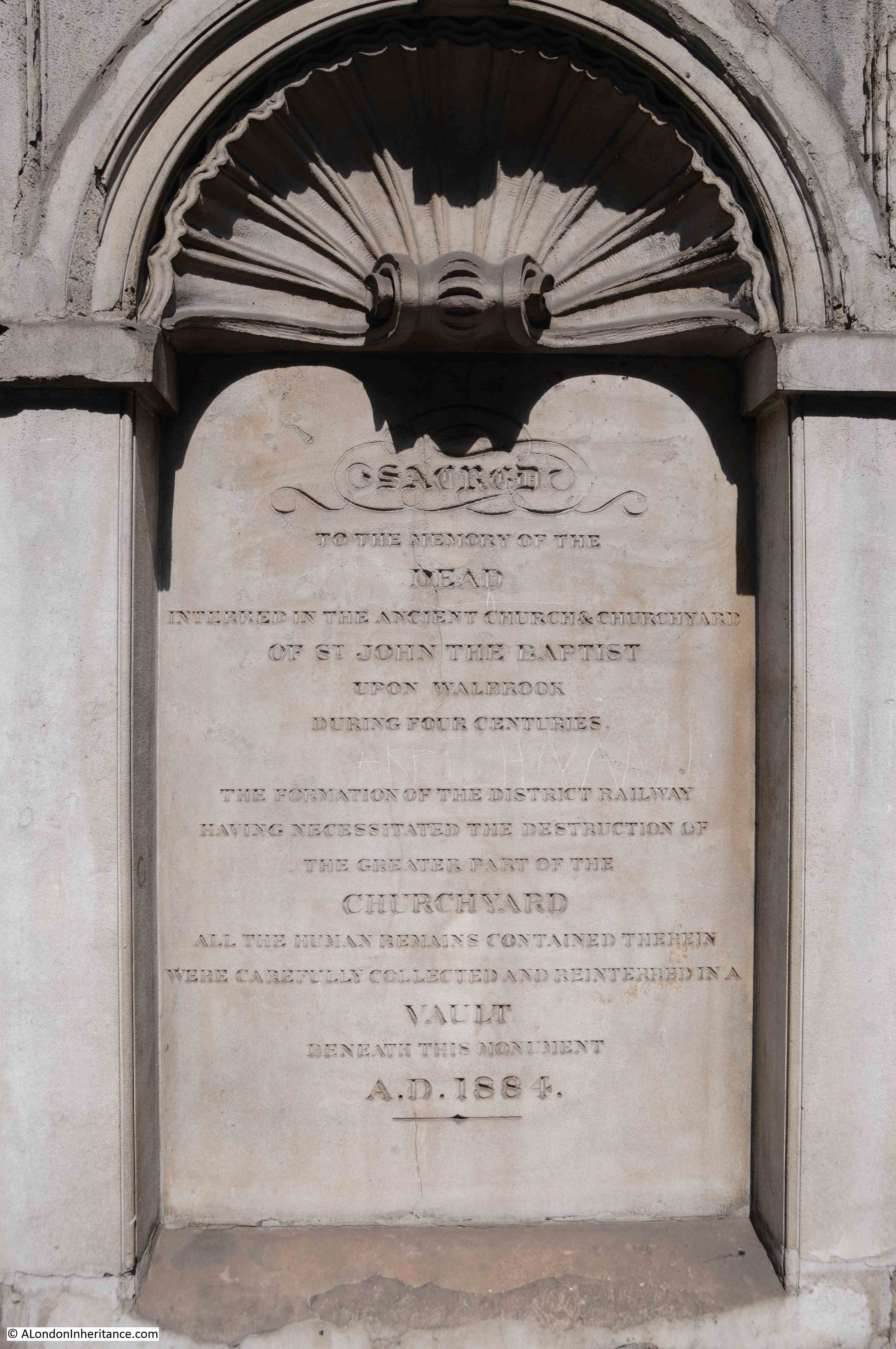

The monument provides some information:

The contrast between letters and stone is not that high in the above photo, so I have reproduced the text on the monument below:

There is much to unpack from the inscription on the monument, and it does not tell the full story.

The church of St John the Baptist upon Walbrook was one of the City churches that was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666, and not rebuilt, so after the fire, only the churchyard remained.

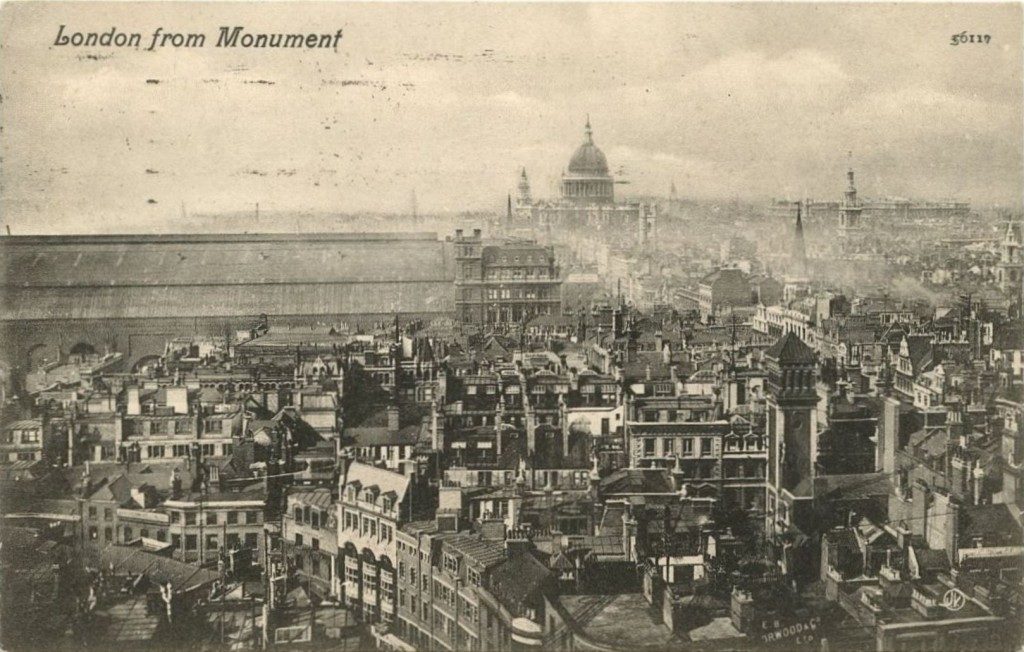

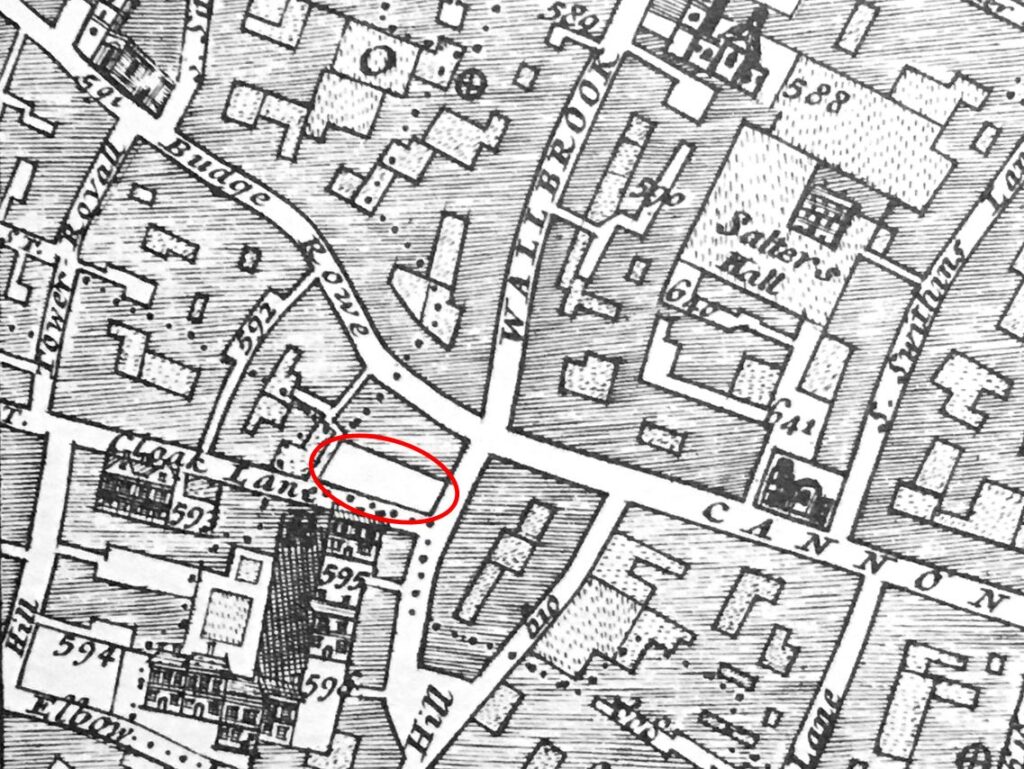

I have circled the location of the surviving churchyard, at the junction of Cloak Lane and Dowgate Hill in the following extract from William Morgan’s, 1682 map of London:

According to “London Churches Before The Great Fire” (Wilberforce Jenkinson, 1917), St John the Baptist upon Walbrook was “Founded before 1291, and enlarged in 1412, and ‘new-builded’ around 1598. The west end of the church was on the bank of the Walbrook, hence the title.”

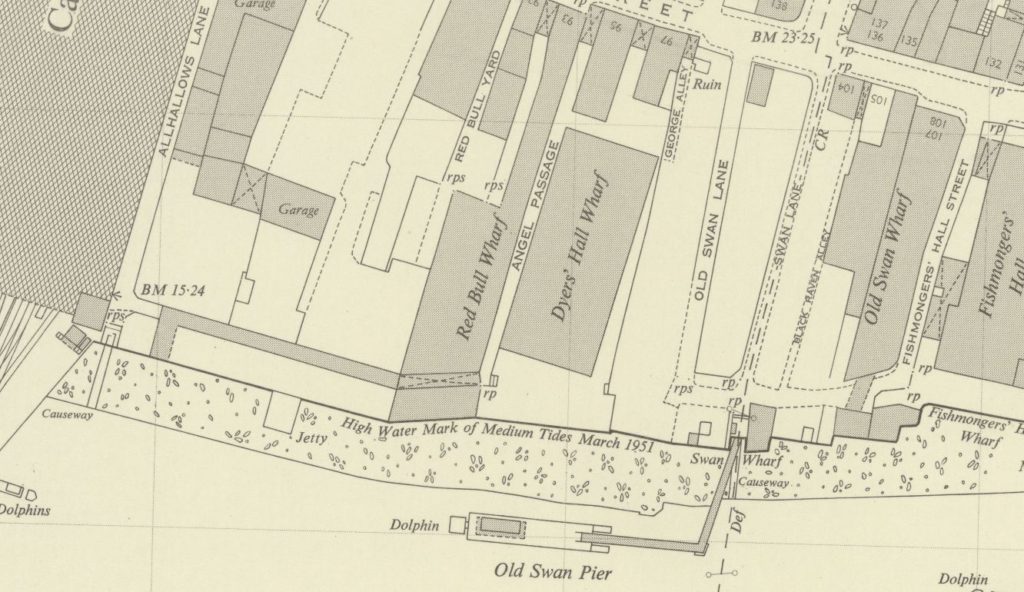

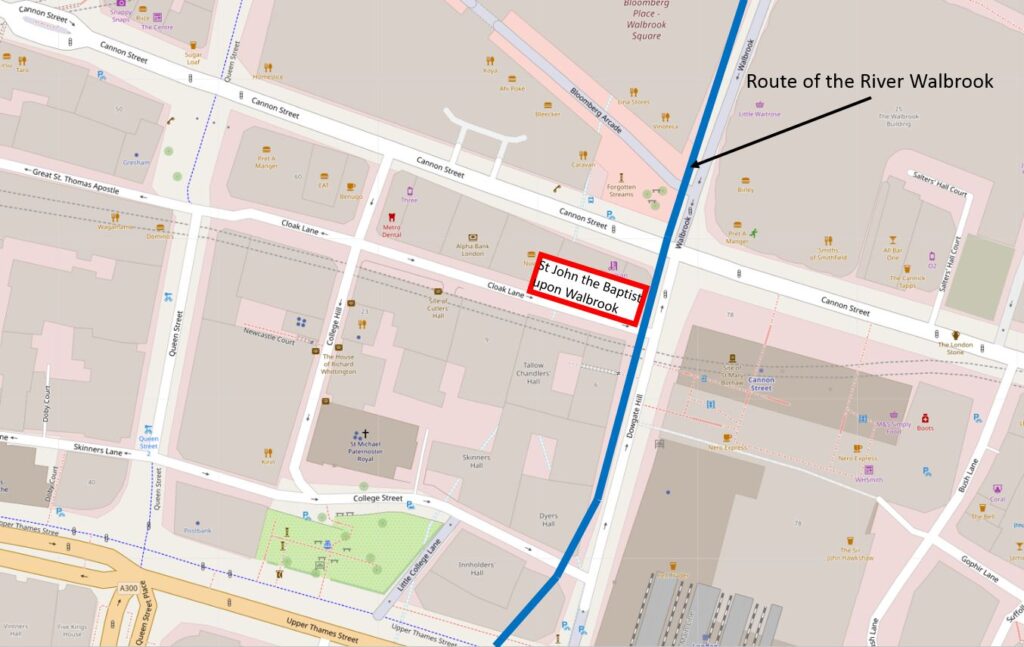

The Walbrook is one of London’s lost rivers, and in the following map I have marked the location of church and churchyard along with the Walbrook which made its way down to Upper Thames Street which was the early location of the Thames shoreline (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The book states that the west end of the church was on the bank of the Walbrook. This is possibly an error as the eastern end of the church would have been on the Walbrook, or it should have read that the church was on the west bank of the river.

It is possible that the Walbrook ran further to the west than shown in the above diagram, however all the references I can find are to the river running roughly on and alongside Dowgate Hill.

The text on the monument mentions the District Railway, and the title for the blog is about the Circle Line. I will explain why I have used the Circle Line later in the post, however stand next to the railings alongside the monument, and a grill can be seen in the floor. Wait a few minutes and the sounds of an underground train can be heard coming up through the grill.

After the 1666 Great Fire, the church was not rebuilt, the churchyard remained, and would do so for the next 200 years. Buildings alongside did encroach on the churchyard, however it was still there in 1880. In the next few years there was some major construction work in Cloak Lane which would result in the loss of the churchyard.

This construction work was for an underground railway that in the newspapers of the time was referred to as the Inner Circle Railway. The following article from the East London Observer on the 31st May 1883 provides some background:

“THE INNER CIRCLE RAILWAY. With much less outward demonstration than might have been expected, considering the importance and magnitude of the works, there is now being contracted in the City of London an underground railway which, by uniting the Metropolitan and District systems, will complete the long looked for Inner Circle Railway, and be of immense service to the travelling public and the metropolis.

The Acts of Parliament under which these works are being carried out were obtained in the names of the joint companies – that is to say, the Metropolitan and the Metropolitan District. They authorised the construction of a railway to commence by a junction with the District line at Mansion House Station, and to run under some houses south of the thoroughfare known as Great St Thomas Apostle, crossing Queen Street, then going along the south side of Cloak Lane, across Dowgate Hill, to the forecourt of the South-Eastern Cannon Street Station. Here is to be made a station.

The line is then to pass under the centre of Cannon Street, crossing King William Street, and is then to swerve slightly south. Between this point and Pudding lane is to be a second station, which will serve the busy district around it, including Gracechurch Street, Lombard Street and Billingsgate. By arrangement with the Corporation and the Metropolitan Board of Works, the narrow thoroughfares of East Cheap and Little Tower Street are to be widened on the south side, and Great Tower Street on the north side. The railway is to pass under the centre of the roadway, and will be constructed simultaneously with the new street. the line will then branch slightly to the north, and between Seething Lane and Tower Hill, another large station is to be built.

The line is then to pass by Trinity Square Gardens, joining the piece of railway already constructed.”

So by joining existing lines at Mansion House and Tower Hill, the new line would form what we know today as the route of the Circle and District lines between Mansion House and Tower Hill.

The Railway News (which also called the line the Inner Circle line) on the 18th of August 1883, provided additional technical information on the new line:

“From the Mansion House station to Tower Hill, there is no part of the line on a curve of less than 10 chains radius; the length from Cannon Street to King William Street is straight. The successive gradients are from the level at the Mansion House to a descent by a gradient of 1 on 100, followed by a rise of 1 in 355, then 1 in 100, next to 1 in 321, for 334 yards and then a fall of 1 in 280 for the remainder.”

I never fail to be impressed by the accuracy achieved in measuring and building these early lines, without the surveying equipment that we have available today.

Look through the grills and some of the monuments from the old churchyard have been mounted on the wall behind:

The new railway was just below the surface and was partially built using the cut and cover technique where the ground would be excavated to build the railway, which would then be covered over, with roads or buildings then completed on top.

Where cut and cover was not used, the railway would be tunneled underneath buildings, undercutting the foundations, bit by bit, with arches being built as the tunneling progressed to support the building above.

Railway News provides some detail:

“Near the western end of the line 200 feet of girder-covered way has been built between Queen Street and College Hill, and a large portion of the side wall has been advanced to Dowgate Hill. In this vicinity an important work, viz, a diversion of the main outfall sewer, has been successfully completed. It was lowered about 14 feet, and the length of this work from north to south being about 600 feet. The north side wall for the Cannon Street station, is also built, and rapid progress is being made with the excavations.”

The total distance of the new line between Mansion House and Tower Hill was 1,266 yards.

Behind the grills – an 1892 Walbrook Ward boundary marker:

The above extract refers to a diversion of the main outfall sewer in the vicinity of Dowgate Hill, which possibly was the sewer running down Dowgate Hill that carried what was left of the Walbrook river.

During excavation work for the new railway, there were a number of finds, which add to the question of the original route of the Walbrook.

In the book “London – The City” by Sir Walter Besant, he quotes from the notes of the resident engineer of the works, Mr. E.P. Seaton: “At the west end of the churchyard was found a subway running north and south. The arch was formed of stone blocks (Kentish rag) placed 3 feet apart, the space between filled up with brickwork. The flat bottom varied from 2 to 4 feet in thickness and was formed of rubble masonry.

A portion of the arch had been broken in and was filled with human bones. the other parts of the subway or sewer were filled with hand-packed stones. this is supposed to be the centre of the ancient Walbrook (this supposition is quite correct) and made earth was found to a distance of 35 feet from the surface. Clay of a light grey colour was then found impregnated with the decayed roots of water plants.

The foundations (it is a matter of regret that no plan of the foundations was taken; the opportunity is now lost forever) of the old church of St John the Baptist were discovered about 10 to 12 feet from the surface and composed of chalk and Kentish ragstones. They ran about north-north-east to south-south-west. Piles of oak were found which seem to denote that the church was built on the edge of the brook, which must have been filled up during Roman occupation, as numerous pieces of Roman pottery were found.

The bottom of the Walbrook valley was reached at 32 feet below the present street level, and is now 11 feet below the level of the lines in the station. During the excavations the piles and sill of the Horseshoe bridge which crossed the Walbrook hereabouts were also found near the churchyard, together with the remains of an ancient boat. These were unfortunately too rotten to preserve, but a block of Roman herring-bone pavement, formerly constituting part of a causeway of landing-place on the brook, is now at the Guildhall Museum. It was found beneath the churchyard 21 feet below the present level of the street.”

Besant can at times be unreliable, however as he is quoting from notes by the resident engineer, and the works were not long before the book was published, they should be an accurate record of finds during the work.

The finds imply that the Walbrook did run to the west of the church, so was further west of the route shown in the earlier diagram and was slightly further west of Dowgate Hill, or perhaps it was a separate channel or ditch.

There is another reference to the Walbrook, and its route in a report on the construction of the railway in the Standard on the 21st April, 1884, which refers to the sewer along Dowgate Hill that ran along the route of the Walbrook, needing to be lowered to make space of the railway. After completion, the sewer and Walbrook ran under the new rail tracks. The report describes the Walbrook as “flowing into the sewer down a flight of steps”.

These layers of history and archeology below the current surface of the City are really fascinating. We really do walk on London’s buried history when we walk the streets, and Besant’s description hints at what has been lost over the centuries, particularly during significant construction works of the later 19th and early 20th centuries, when these sites did not have an archeological excavation before construction commenced, and before the preservation techniques were available, that would have been needed to preserve the boat and wooden piles that were found.

Another of the memorials behind the metal grill – I wonder what John (died in 1804) and Uriah (died in 1806) Wilkinson would have thought if they knew their memorial would be hidden behind a metal grill, and above an underground railway?

The extract from Besant’s book mentions the “Horseshoe bridge which crossed the Walbrook hereabouts were also found near the churchyard”. The bridge also has a connection with Cloak Lane.

According to Henry Harben’s Dictionary of London (1918), the name Cloak Lane is of relatively recent origin, with the first mention being in 1677. Prior to this, the street was named Horshew Bridge Street after the bridge over the Walbrook.

A possible origin of the name Cloak Lane is from the word “cloaca” which is a reference to a sewer that once ran along the street down to the Walbrook, however as the name of the street is much later than the sewer and when the word “cloaca” would have been used, it is almost certainly not the source, which remains a mystery.

The first mention of this bridge dates back to 1277 when it was called “Horssobregge”, and was a bridge over the Walbrook close to the church of St John upon Walbrook.

During the medieval period, property owners in the neighbourhood of the bridge were responsible for keeping it in good repair. Around 1462, the Common Council ordained that land owners on either side of the Walbrook (which was then described as a ditch) should pave and vault the ditch, and if a landowner failed to comply, their land would be given to someone who would take on this responsibility.

Following the paving over of the Walbrook, the bridge became redundant, fell into disrepair and was eventually taken apart.

The following photo is looking down Cloak Lane towards Cannon Street Station, the entrance to the Underground station can be seen at the far end of the street, across Dowgate Hill.

I have arrowed two locations in the photo. The orange arrow is pointing at the location of the memorial, and was the location of the church and graveyard.

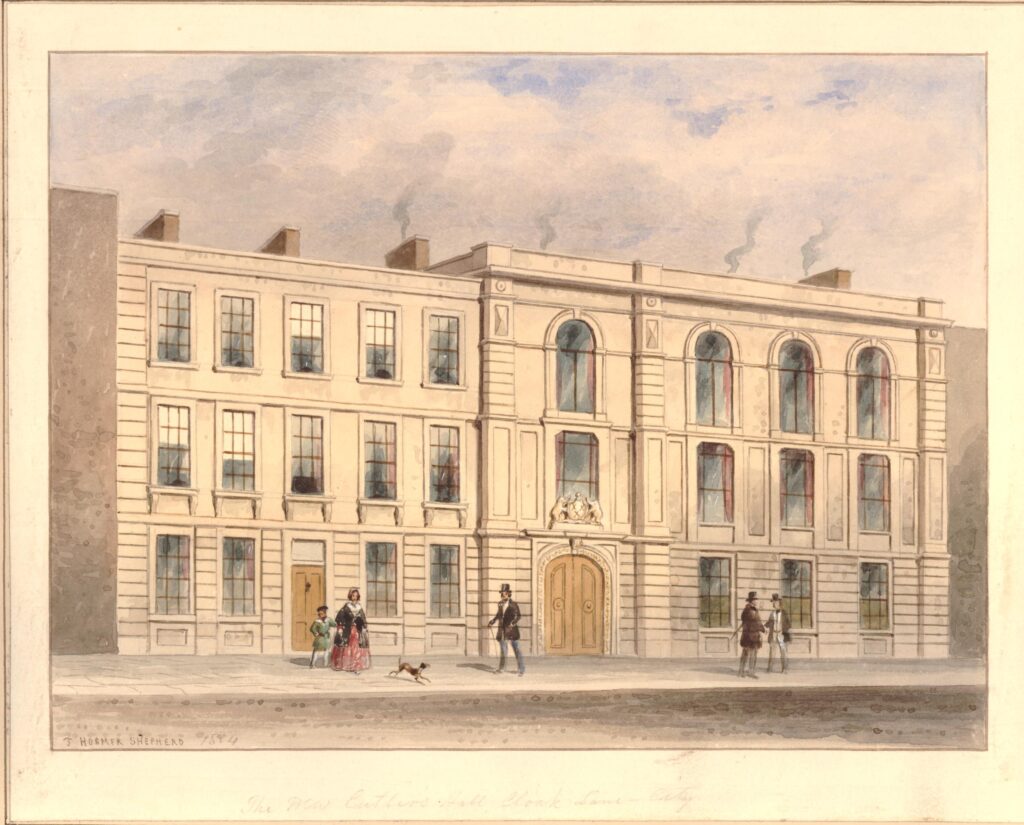

The second arrow is pointing to the site of another building that was demolished to make way for the works to construct the new railway – Cutlers Hall:

Cutlers Hall was the home of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers, one of the City’s ancient companies. When the Cutlers were organised into a Company, the trade consisted of the manufacture of swords, daggers and knives. As an example of how specialised a City workman was at the time, there were seperate trades for hafters, who made the handles, along with blacksmiths and sheathers (who made the sheath in which a sword or knife would be stored).

The first mention of the Cutlers dates back to 1328 when seven cutlers were elected to govern the trade, and in December 1416, a Royal Charter was granted to the company.

Hafters, sheathers and blacksmiths were gradually incorporated into the Cutlers Company.

The hall of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers was in Cloak Lane from the earliest days of the company, until the arrival of the Inner Circle Line, when the hall was demolished in 1883, having been the subject of a compulsory purchase order.

The Cutlers purchased a new plot of land in Warwick Lane, had their new hall designed by the Company’s Surveyor, Mr. T. Tayler Smith, and the new hall came into use in March 1888. The Cutlers have remained at the Warwick Lane site ever since.

The following print shows Cutlers Hall in Cloak Lane as it appeared in 1854 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

There were many newspaper reports on the construction of the new railway, and the methods used to minimise disruption to the City above.

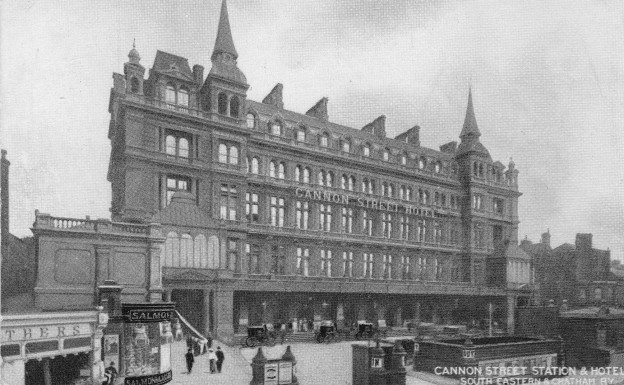

Cannon Street Station originally had a forecourt between the station entrance and Cannon Street. The tunnel needed to be built under the forecourt, and the method used to avoid disruption to the station was that the contractor:

“Provided 250 men for the occasion and 50 more as a reserve, the intended work was commenced after the dispatch of the Paris night mail, and then the busy hands plied their busiest. The paving slabs were removed; the twelve inch timbers were laid on the bare ground, three-inch planking put across them, and again three-inch planking over these. And in the morning when Londoners came to their duties in the City they were astonished to see the fore-court paved with wood, and an alteration completely effected, of which there was not a symptom or indication when they went home from their duties the evening before. Having thus laid their roof on the surface the contractor could carry on burrowing to his heart’s content. Beneath the wood platform a heading was soon driven through the soil; and the contractors went on their way below, whilst the cabs and the passengers were going on above”.

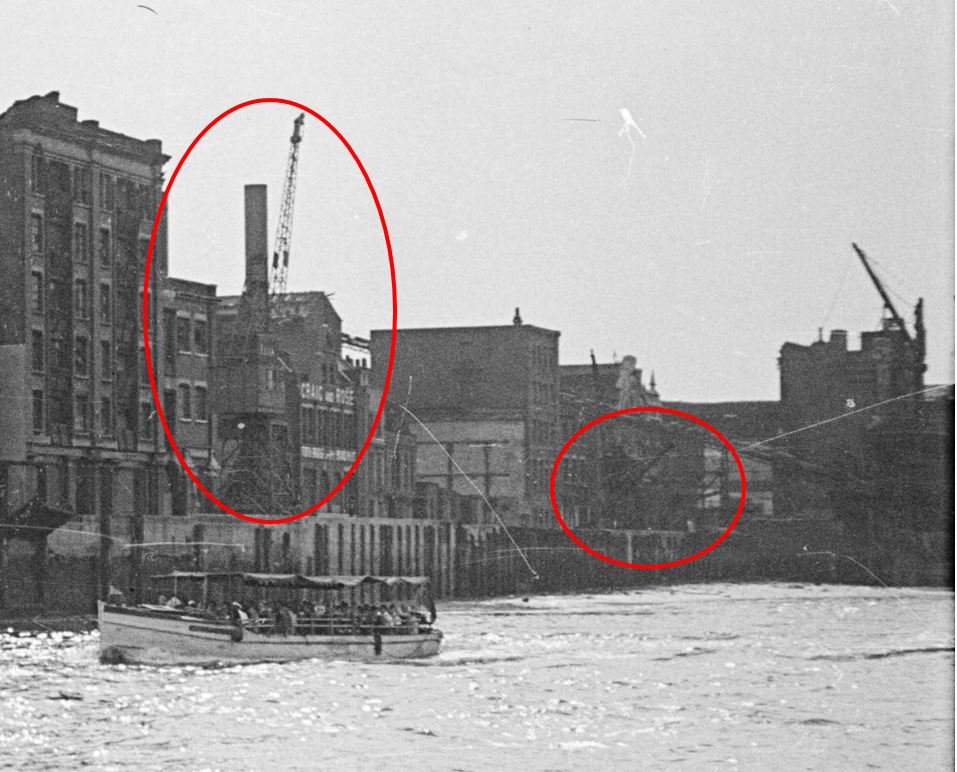

The following photo shows the Cannon Street Station Hotel and entrance to the station behind. The forecourt under which the Inner Circle Line was dug can be seen in front of the hotel.

The monument in Cloak Lane is a perfect example of what fascinates me above London’s history. There is so much to find in one very small section of street, and that London is not just what we see on the surface, there is so much below the streets, lost rivers, centuries of history, remarkable examples of construction methods used to build the start of the underground system in the 19th century, and so much more.

If you take a train on the Circle or District line to or from Cannon Street Station, on the western side of the station, recall the Walbrook and the church and cemetery.

I have also added trying to find out about the fate of the finds from the construction of the railway, given to the Guildhall Museum, and which are now hopefully at the Museum of London. And if anyone from TfL reads this post – if you could let me have a look behind the metal grills in Cloak Street – it would be much appreciated !