This year has been a good year for exploring disused underground tunnels. The London Transport Museum and the British Postal Museum have arranged a number of tours throughout the year, and last Thursday I took my last tour of the year, to the disused London Underground Station at Down Street.

You could argue that once you have seen one old underground tunnel, you have seen them all, however each location is unique and they have their own story to tell of London’s development and recent history. Down Street is no exception and held a critical role in the running of the country’s transport network during the last war.

Down Street station is, as the name suggests, in Down Street which runs from Piccadilly to Hertford Street.

The station opened on the 15th March 1907 on the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (part of today’s Piccadilly line), between the stations at Green Park (or as it was called Dover Street) and Hyde Park Corner.

The station however did not meet expectations on passenger numbers for a number of reasons. Green Park and Hyde Park stations were very close by, the station was in a side street rather than on Piccadilly, and the residents of this affluent area tended to have their own private transport rather than use the Underground.

As a result of the station’s limited use, it closed on the 21st May 1932.

The street level station in Down Street as it is today:

The exterior design of the station was by Leslie Green who was responsible for a number of other stations on the underground. The design and tiling were used on many other stations and clearly marks out the previous function of the building.

Entrance to the platform level today is via the emergency stairs. An original World War 2 sign at the top of the stairs hints at the use of the station during the last war.

Looking down the stairs:

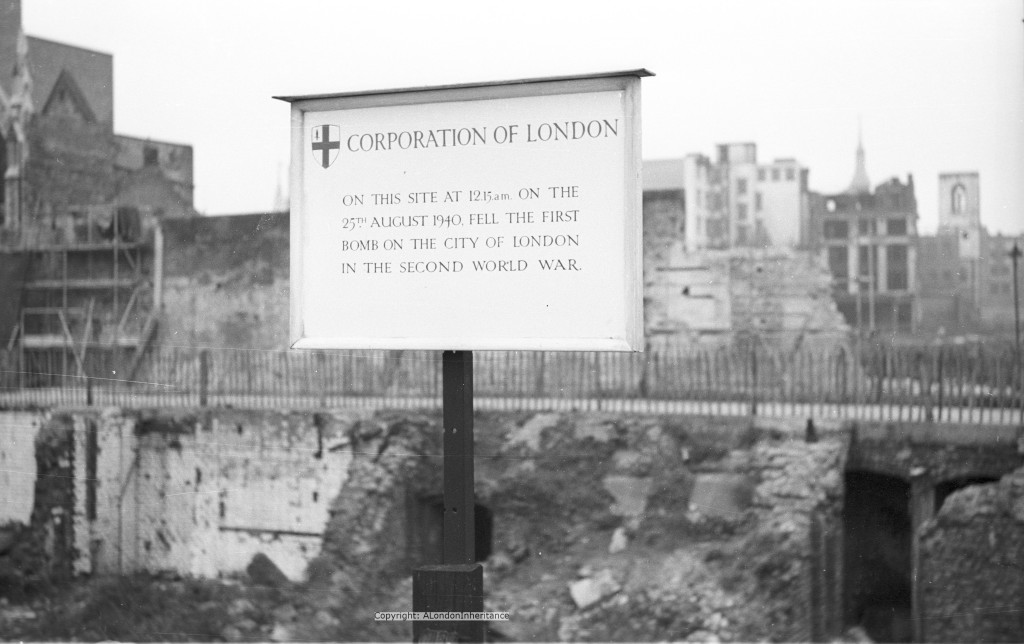

Prior to the start of the last war, committees were formed to coordinate key elements of the country’s war effort. One of these was the Railway Executive Committee (REC) and they were in need of a location which would protect the staff and their telephone communication systems.

The role of the REC was to coordinate and manage the wartime operation of the railway companies and the London transport system.

The REC had representatives from each of the rail companies and the London Passenger Transport Board along with telephone communications with each of these organisations. The REC would coordinate the essential movement of troop trains, ammunitions and equipment, raw materials and other goods critical to the war effort, and manage the impact of enemy bombing on the rail network

At the bottom of the stairs, more signs hinting at the previous use of the station.

Looking back at the bottom of the stairs. The sign on the wall indicates the depth below ground, with the height of the shaft being 22.22 meters.

The tunnels were converted to provide accommodation for the REC by both London Transport and the London Midland & Scottish Railway.

London Transport were responsible for structural changes and the Railway Company fitted out the tunnels so they were suitable to provide office and living accommodation for the staff of the REC.

Many of the tunnels were plastered or boarded over, partition walls installed and furnished using stock from both the above ground office of the REC and from Railway Hotels, so the quality of furnishing was reasonably high.

This is the tunnel that held the committee room of the Railway Executive Committee. Originally the tunnel walls were boarded and partition walls installed with doors providing entry and exit to the rest of the tunnels. The white tape on the floor marks the position of the board room table.

One of the side tunnels was converted to provide bathroom facilities for those who would work a shift of several days below ground. The remains of these still exist, although the decay of the past 70 years is clearly evident. These facilities are in individual alcoves along the side of one of the tunnels. It was fascinating to peer into these as they are in almost total darkness. I had to use flash for these photos.

Bath in the photo above and sink in the photo below.

Double sink unit. Really good that the historic value of these facilities has been recognised with signs warning not to remove or damage these objects.

An original water heater.

Photo showing how the tunnels were partitioned to provide a narrow walkway past the facilities installed in the tunnel on the right.

As well as the Railway Executive Committee, Down Street also provided accommodation for Winston Churchill at the height of the Blitz.

The original facilities in Whitehall and the Cabinet War Rooms were not considered strong enough to withstand a direct hit by high explosive bombs and whilst new facilities were being constructed, Churchill needed a secure central London location and Down Street provided this service from October to December 1940.

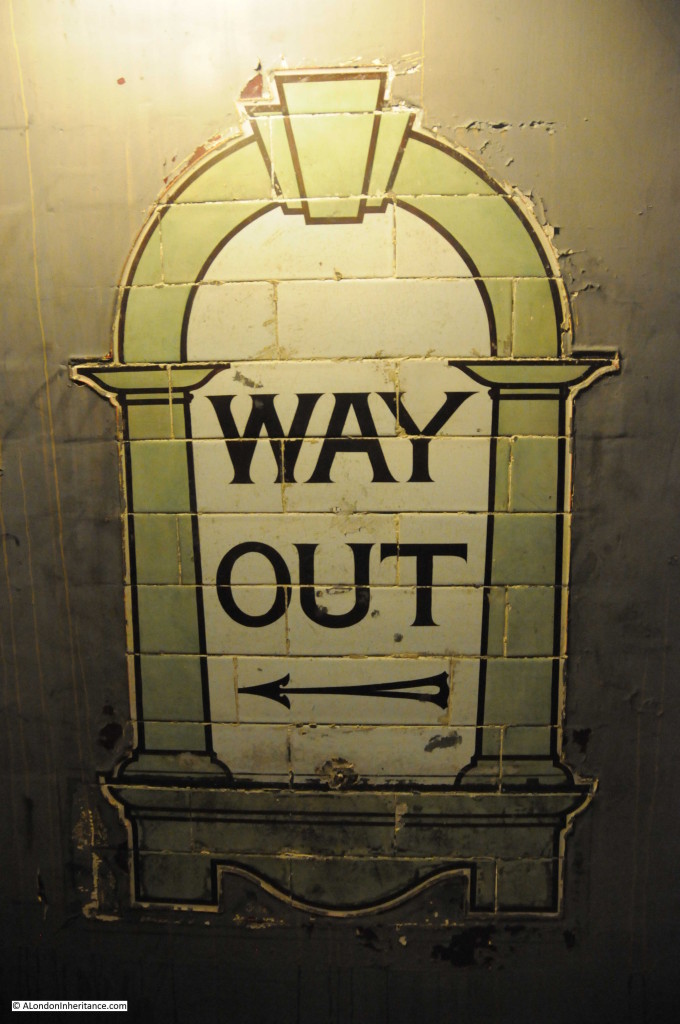

Despite the amount of change needed to accommodate the REC for the duration of the war, much of the original station signage remains:

To support the work of the REC, communications were needed with the rest of the country’s railway systems. For the time, an advanced telephone system was installed for this purpose and some of this switching equipment still remains:

Another view of one of the tunnels showing how they were partitioned with narrow walkways providing access across the complex:

As well as washing and sleeping facilities, the occupants of Down Street also needed to be fed. The station had a kitchen capable of feeding the 40 staff based on site plus any visitors.

The Piccadilly line still passes through the station. As part of the construction work to make the station suitable for the REC, a wall was built along the length of the platform edge. This still remains with occasional entrances through to the section of the tunnel with the train tracks.

The noise of passing underground trains echoed throughout much of the station. It must have been difficult to work, and to sleep for those off shift during the time when trains would still be running.

Stairs up to the tunnels which connect with the lifts bringing passengers to and from ground level.

Some of the original station signage remains behind later paint, plaster and the accumulated dirt of many decades. Later signage helps with orientation in the tunnels.

An alcove built during the war to accommodate additional communications equipment:

More original signage:

Curving tunnels always fascinate. What is around the corner?

Here is the original lift shaft. Lifts were installed during the original station construction. As part of the work to ready the station for occupancy by the REC, a thick concrete cap was installed to ensure that the impact of any surface bombing could not reach the platform levels through the lift shaft.

The REC continued to use Down Street until the end of 1947. Since then, there have been no other occupants of the station. Many of the partitions were removed to allow various elements of underground signalling and communications to be installed, but the rest of the REC facilities have been left in slow decay.

The main use of Down Street has been to provide ventilation to the Piccadilly Line which is the role the lift shaft provides today.

Looking up the lift shaft:

These holes in the wall at the bottom of the lift shaft provided the entrance from the platforms tunnels to the lifts.

The facilities in Down Street were designed not only to provide protection from explosive bombing, but could also be sealed against gas attack with air filtration equipment providing breathable air for the REC staff. An original wartime door.

Back up to the surface and heading towards the street:

Down Street is a fascinating station. It only served the Piccadilly Line for a short period of time, but then played a key role in the war, maintaining the efficient coordination and running of the country’s railways.

The London Transport Museum is performing an excellent service in opening up these old stations with well run tours and very knowledgeable guides. The tour of Down Street is highly recommended to see the remains of the station’s wartime use.

If you do visit Down Street, near by is Shepherd Market. Also well worth a visit which I covered here.