Moorgate Station has a complex mix of different transport lines. The Northern, Circle, Metropolitan and Hammersmith & City underground lines and Great Northern National Rail line.

The station both above and below ground has also had a complex history, as lines were built and extended, use of lines changed, intended extensions came to nothing, and the surface station disappeared under a wave of post-war building.

Change is continuing as Moorgate Station will be at the western end of the Liverpool Street Station on the Elizabeth Line.

The London Transport Museum included Moorgate as a new tour in their Hidden London series of station tours and back in February on a chilly Saturday afternoon, I arrived at Moorgate looking forward to walking through the hidden tunnels of another London underground station.

The following photo shows one of the entrances to Moorgate Station (the brick building to the right) along with the construction area for Crossrail / Elizabeth Line to the left.

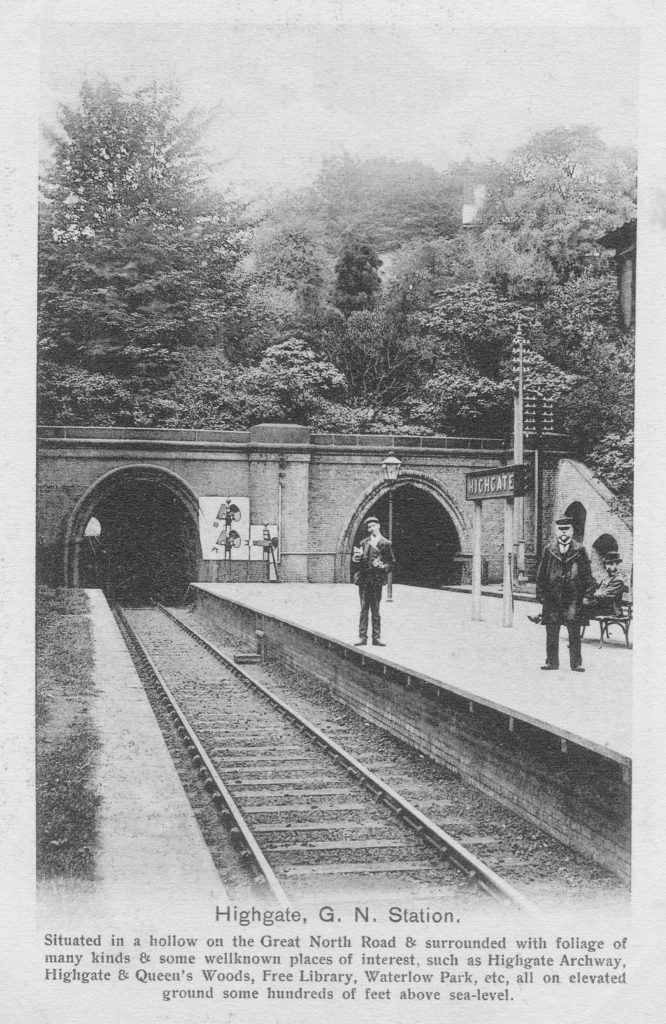

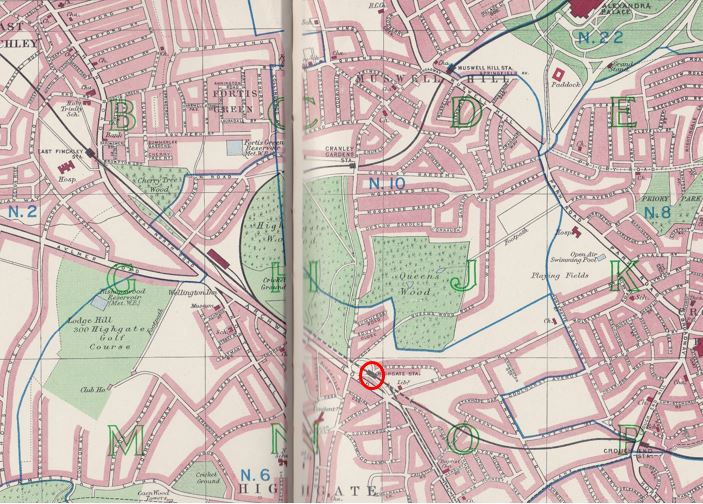

Moorgate started life as a surface station when the Metropolitan Line was extended east in 1865. The station’s appearance was much like any other surface station with open tracks and platforms, and the following Ordnance Survey extract from 1894 shows the station in the centre of the map with lines leading off to the north-west.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

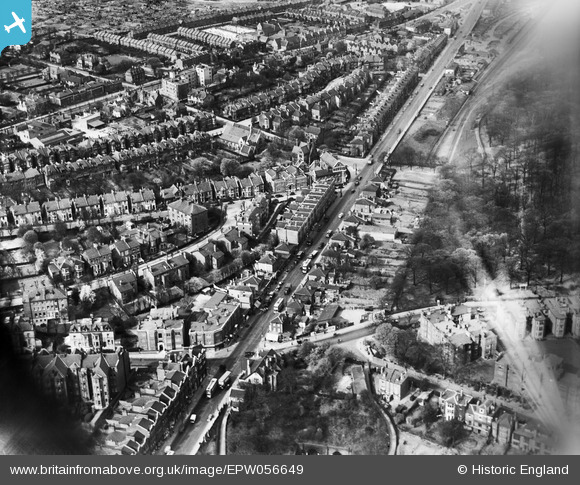

The area was heavily bombed during the last war and Moorgate Station did not escape. The following photo from 1949 shows Moorgate Station at the bottom centre of the map with the rail tracks running north through the space now occupied by the Barbican development.

1940 view of a badly damaged station and burnt out train at Moorgate.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0019308CL

The above view is looking to the east, the burnt out buildings face onto Moorgate, and behind them you can see the domed top of 84 Moorgate, or Electra House, that I used as a landmark to locate the position of one of my father’s photos in my post on London Wall a couple of weeks ago.

Post-war rebuilding of the area around London Wall, the Barbican and Golden Lane Estates led to the re-route of part of the above ground rail tracks into Moorgate, and the station disappearing below a series of office blocks.

Part of the old above ground Moorgate platforms as they appear today.

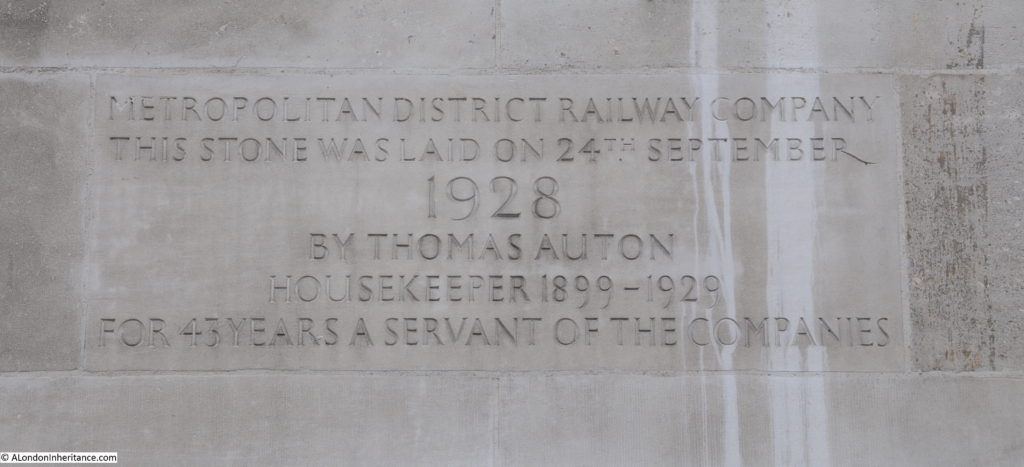

The deep level underground arrived at Moorgate Station in 1900 in the form of the City & South London Railway extension from Borough to Moorgate. This route would be later extended onto Old Street, Angel, King’s Cross and become the eastern leg of the Northern Line, meeting the western leg at Kennington in the south and Camden Town in the north.

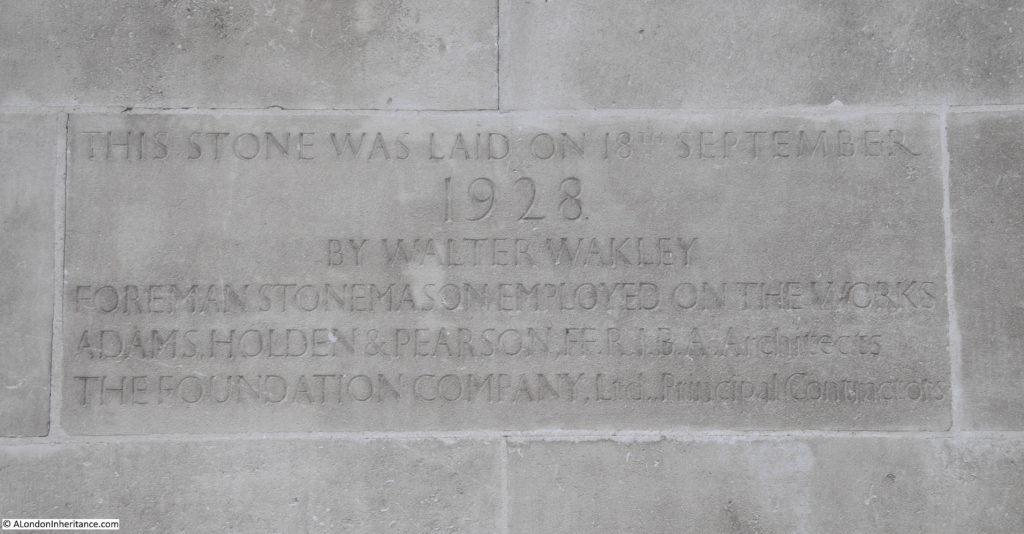

When the original City & South London station was built, lifts were used rather than escalators, so underneath Moorgate today are old lift shafts and access tunnels to these lift shafts, and it was some of these that formed part of the tour.

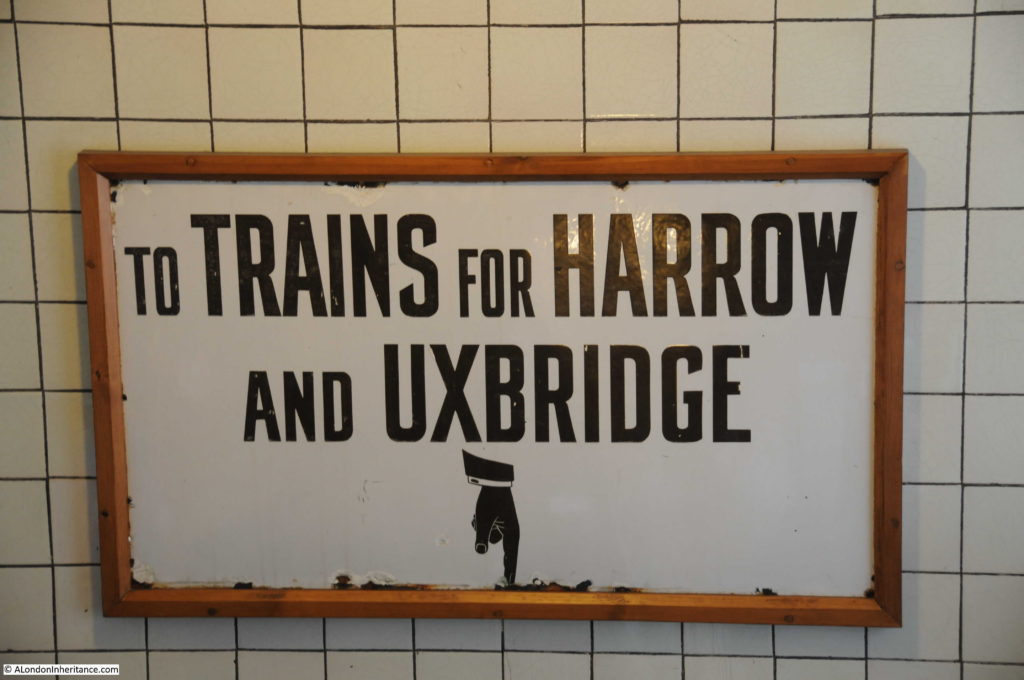

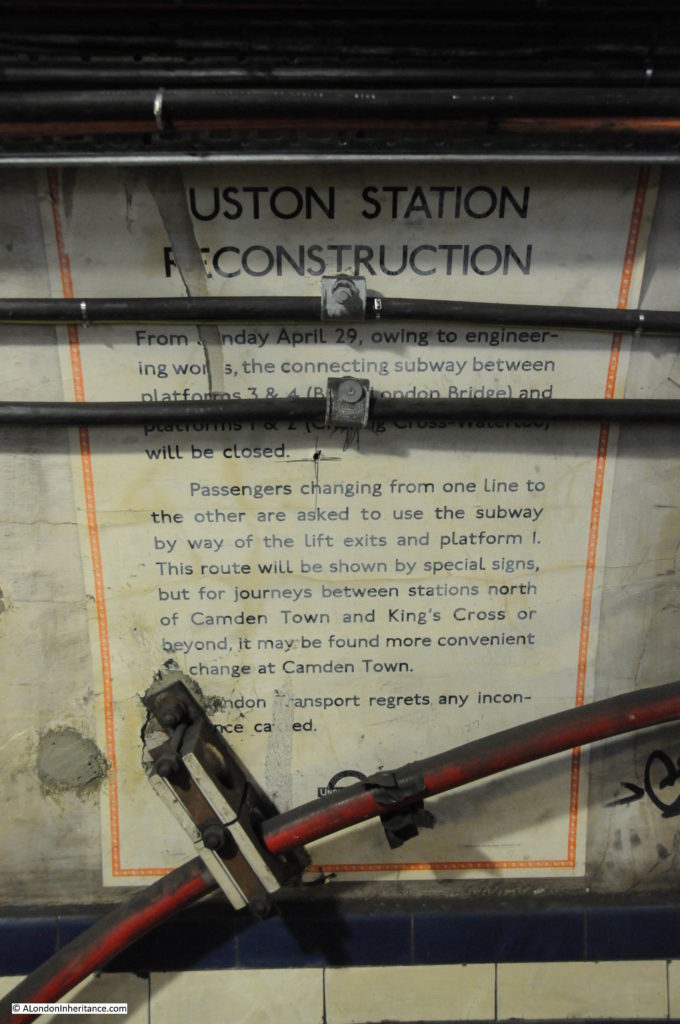

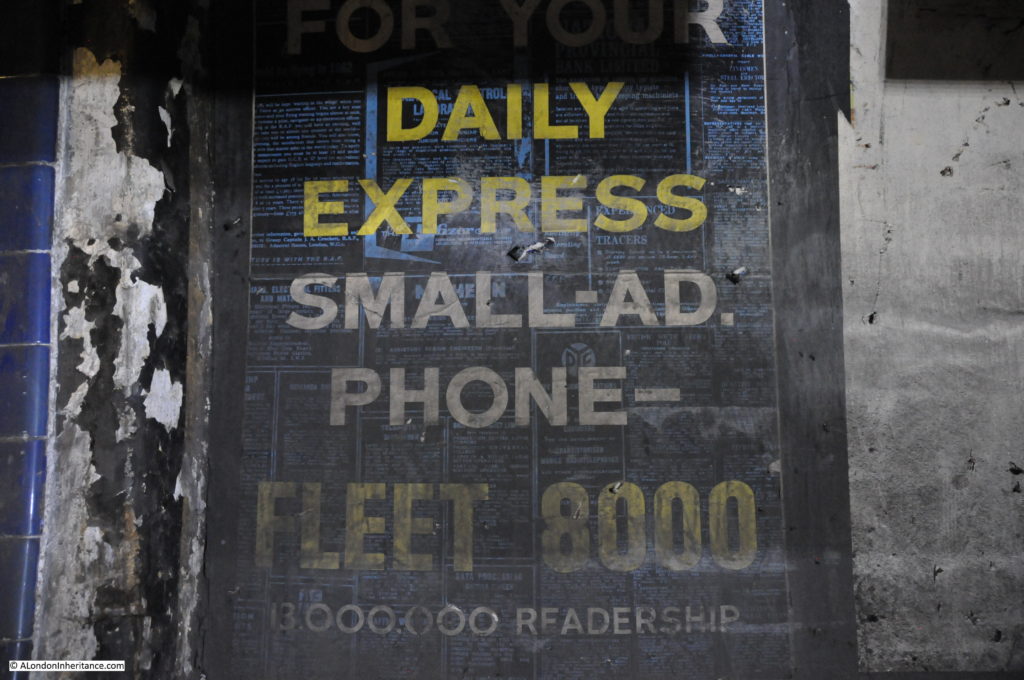

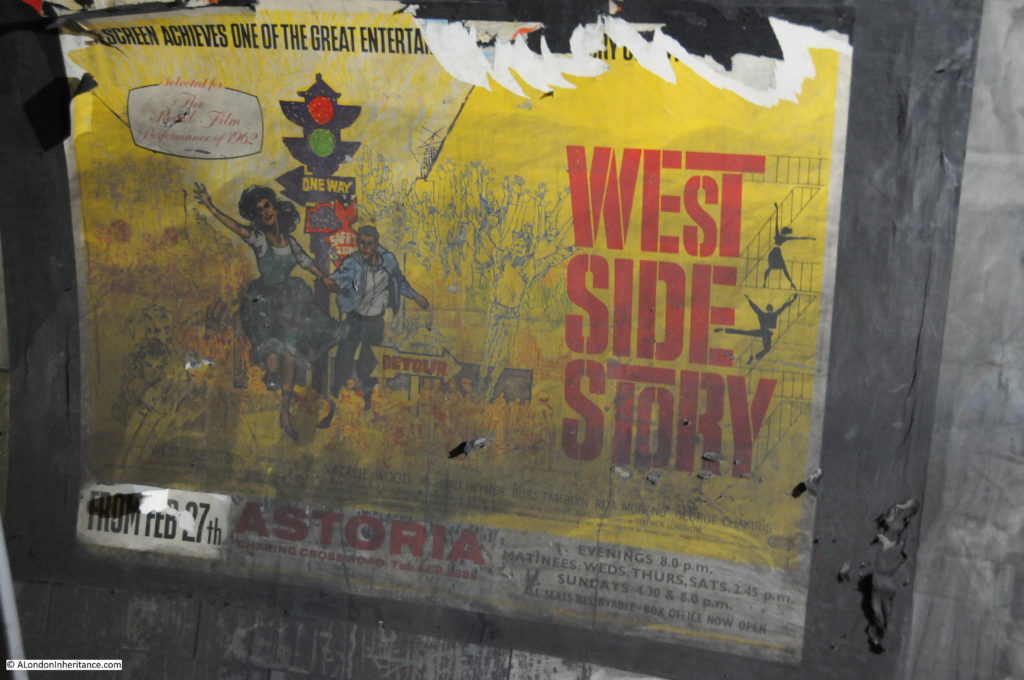

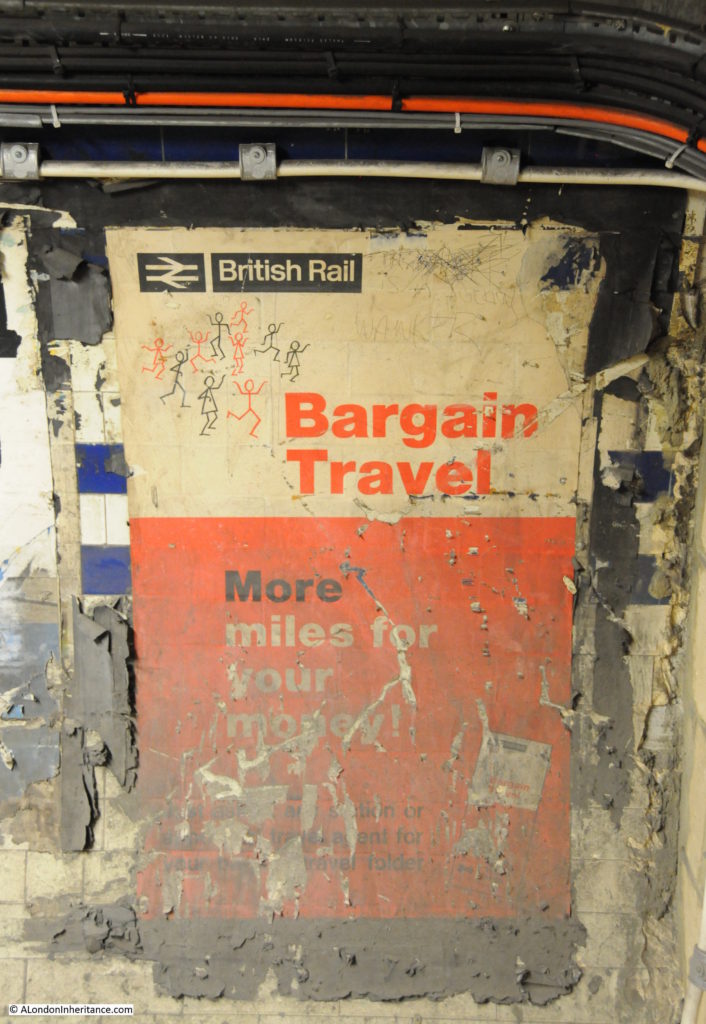

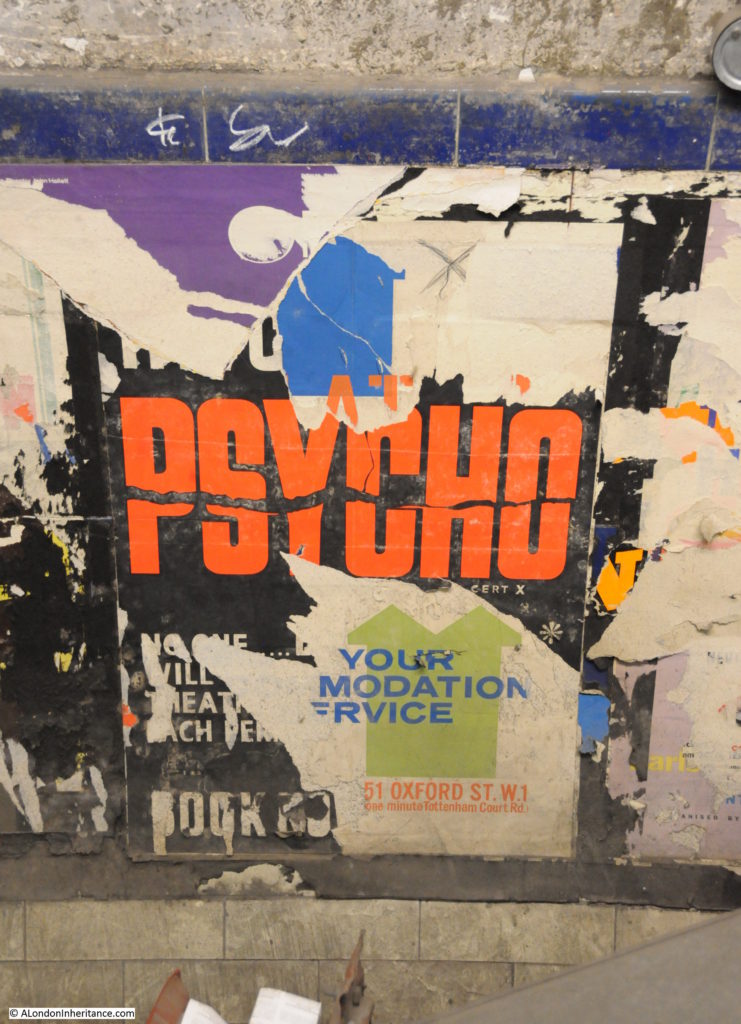

One thing that fascinates me in these tours of disused stations and tunnels is how they can be read very much like an archaeological excavation, although rather than horizontal layers of history, in these tunnels layers are multi-dimensional as new walls are added, utilities installed, old signs and adverts part covered, graffiti added etc.

No Smoking and Way Out To The Lifts (although the final word is now lost):

When the City & South London Railway arrived at Moorgate in 1900, the moving staircase, or escalator was still 11 years away (first introduced at Earl’s Court station in 1911) so deep level stations were dependent on lifts to transport passengers between ticket halls and platforms.

Escalators have now replaced lifts across the majority of London Underground stations, so on the early deeper level routes there are redundant lift shafts to be found, including at Moorgate, where the following photo (with a bit of camera shake due to a slightly long exposure) shows the view up to the top of one of the redundant shafts.

Many of these disused tunnels are now used for storage.

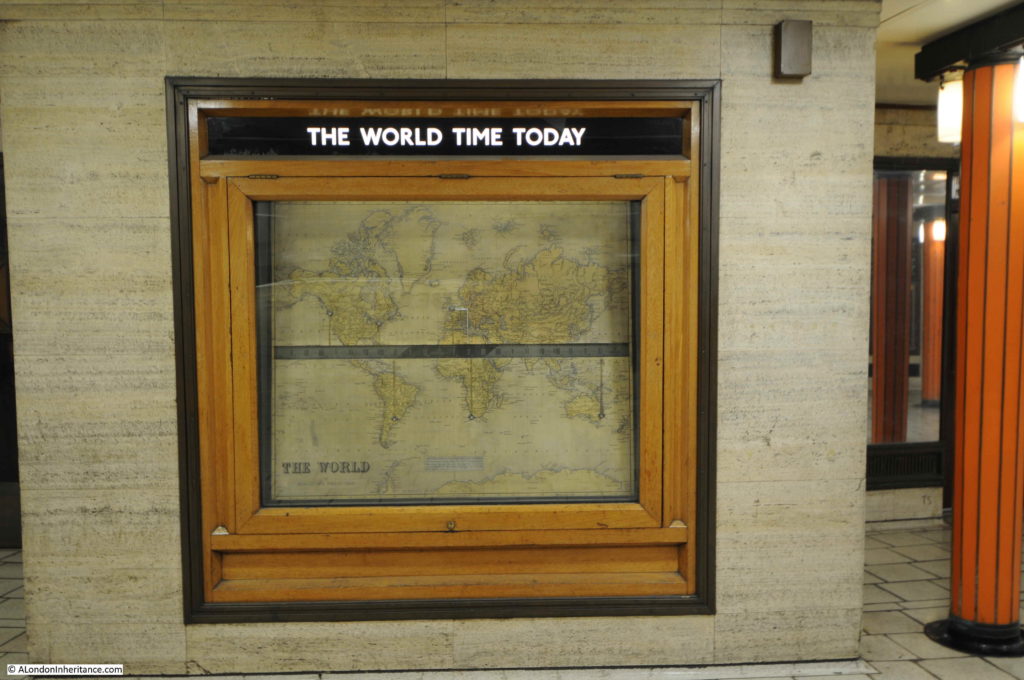

Although you could argue that once you have seen one disused underground tunnel, you have seen the lot, it is the commentary by the Hidden London guides that make these tours so interesting, with their in-depth knowledge of the development of the station, and London’s transport network. However, there is one unique feature at Moorgate which is not found at any of the other station tours.

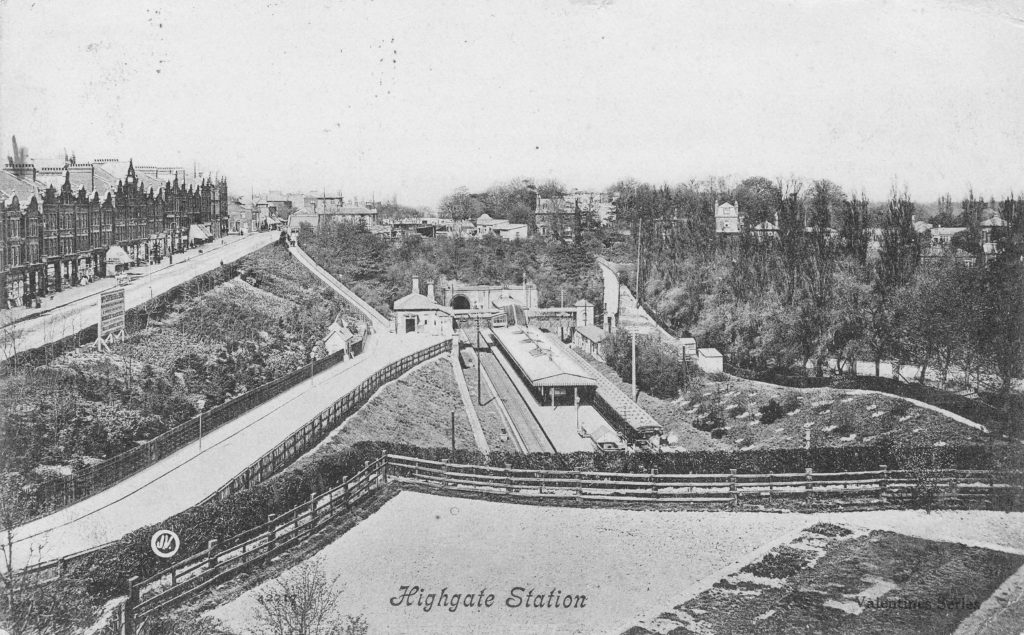

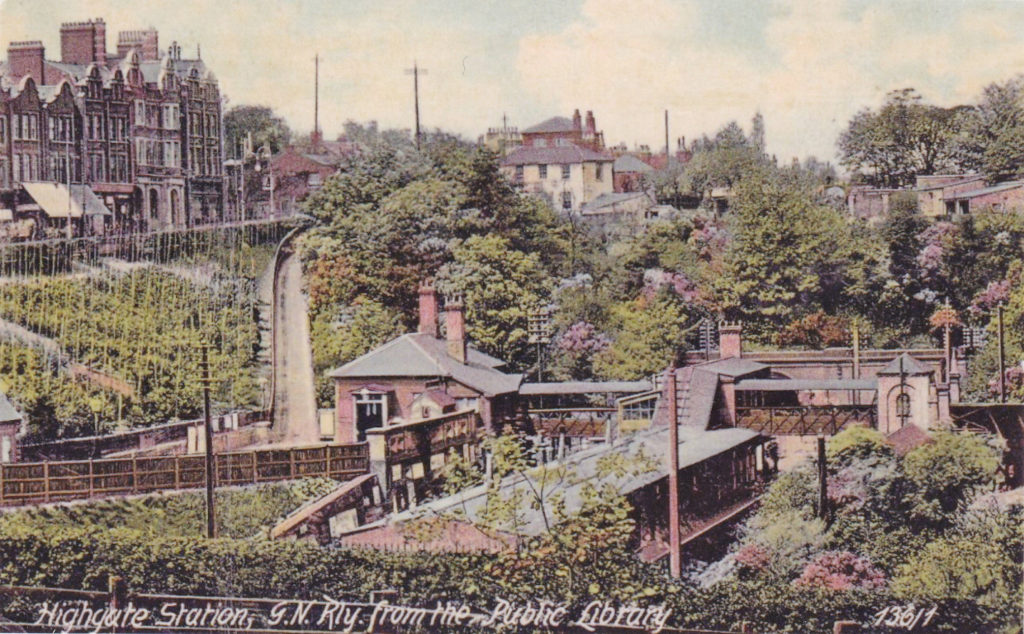

The Great Northern & City Railway was a line originally from Finsbury Park to Moorgate, built with the intention of allowing trains of the Great Northern Railway to run on from Finsbury Park into the City. The tunnels for these trains were larger, at 16 feet diameter to allow Great Northern trains to run into the City.

Whilst the line from Moorgate to Finsbury Park was under construction in 1901, a bill was put before Parliament to allow the extension of the line further into the City with a terminus at Lothbury rather than Moorgate.

The plan being for a sub-surface station on the corner of Lothbury, Gresham Street, Moorgate and Princes Street, just north of the Bank station.

The line from Finsbury Park to Moorgate opened in 1904, but despite having Parliamentary approval, the extension to Lothbury was stopped soon after commencement of work, and despite a couple of attempts to continue, lack of funding resulted in the project stalling, and the Greathead Tunneling Shield used for the extension being left in place at the end of a short stub of tunnel, a long way short of Lothbury.

The Greathead Tunneling Shield is the unique feature of Moorgate:

The Greathead Tunneling Shield was the invention of James Henry Greathead, who developed Brunel’s shield design, from rectangular, with individual moveable frames, to a single, circular shield. Screw jacks around the perimeter of the shield allowed the shield to be moved forward as the tunnel was excavated in front of the shield, with cast iron tunnel segments installed around the excavated tunnel immediately behind the shield.

Greathead’s first use of his shield was on the Tower Subway.

He died in 1896, before the Lothbury extension at Moorgate, however his shield design was so successful that it became the standard design for shields used to excavate much of the deep level underground system.

The Illustrated London News in 1896 recorded the following about Greathead:

“Hamlet thought that a man must build churches if he would have his memory outlive his lifetime, but Mr James Henry Greathead, the well-known engineer, who died on Oct. 21, has left a name which seems likely to survive him for some time by the less picturesque work of making subterranean tunnels.

He developed to its highest pitch the system of tunneling which had been introduced by Brunel, who constructed the tunnel under the Thames at Wapping by means of a shield. Mr Greathead improved this shield and drove it forward by hydraulic rams, while he made such subaqueous work easier by the use of compressed air. The greatest feat in subaqueous boring that has ever been undertaken is the new tunnel under the Thames at Blackwall. It is a curious fact that the great engineer just lived to see the Blackwall tunnel brought to a successful completion and then died.

One of his best known projects was the City and South London Railway, which has been successfully at work for five years; and the new Central London Railway and the similar enterprise on the Surrey side now in progress owe much to the ingenuity of his innovations.”

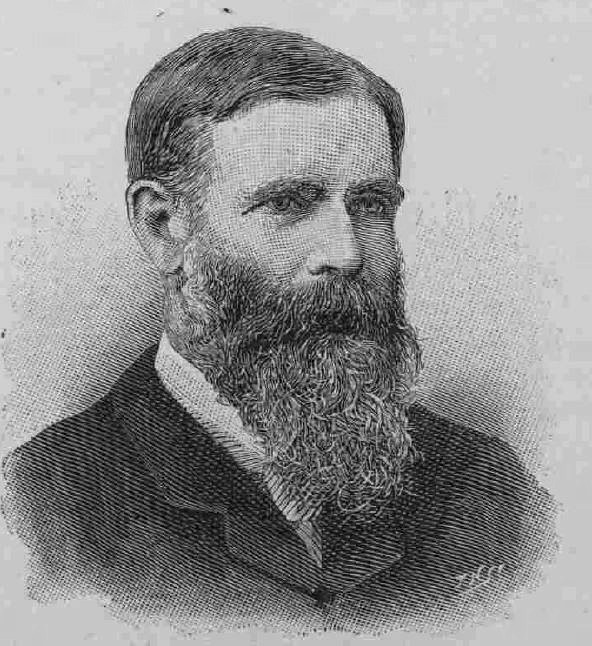

James Henry Greathead:

The Illustrated London News wrote in that 1896 article that his name seemed likely to survive for some time, but I wonder if they would have expected this to be into the 21st century, and a shield of Greathead’s design still being visible in the tunnels under Moorgate.

The tour takes in many of the tunnels of the original station when the lifts were in operation, these tunnels, other side tunnels, changes in level, all contribute to the sense of a maze of tunnels under the streets of Moorgate.

Old advertising on tunnel walls:

Dark tunnel walls and ventilation pipes:

The tour concludes with a view of the next stage of Moorgate’s development, with the entrance from Moorgate Station to what will be the Liverpool Street Station on the Elizabeth Line.

Moorgate has been in continuous development since the very first station in 1865. Connectivity has grown over the years, the surface station disappeared below the post-war development of the area.

The station was the location of the worst peacetime accident on the London Underground, when on the 28th February 1975, 43 people were killed when a train failed to stop and hit the wall at the end of the tunnel at a speed of 35 miles per hour.

In 2009 as part of the Thameslink project some of the widened lines and platforms into Moorgate were closed and are planned to become sidings for the Metropolitan, Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines by the end of the year.

The Elizabeth Line will connect Moorgate with Liverpool Street Station via a 238 metre long shared platform, running 34 metres below the surface.

Hidden London Tours are currently on hold, but when resumed, the tour of Moorgate provides a wonderful opportunity to learn about this complex station, and the chance to see one of the engineering innovations that helped build London’s underground transport network.