The streets of London always have, and always will change. Buildings can disappear almost overnight and be replaced by a very different structure.

I try and photograph buildings and places before any demolition. This can be a challenge given the rate of change, however for today’s post, there are three places I want to focus on which will probably be very different in the years to come.

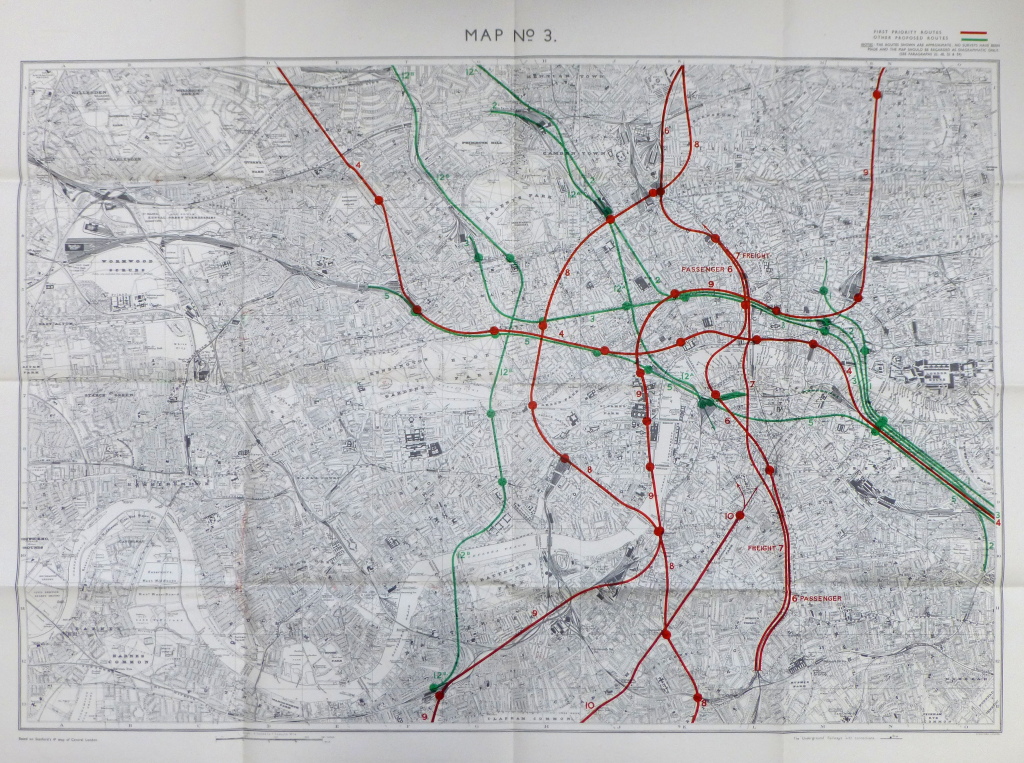

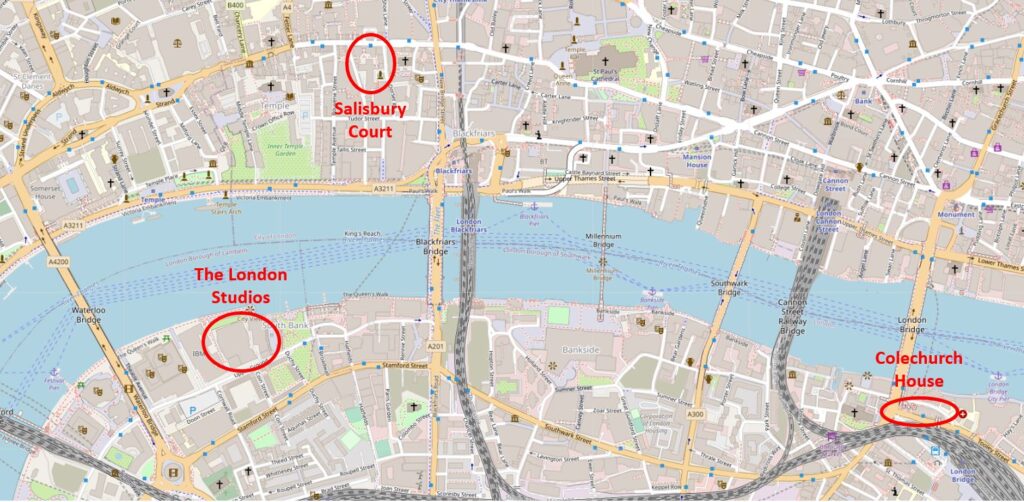

The three locations are shown in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The London Studios / London Weekend Television

Look across the river from the Embankment by Temple Underground Station, and this is the view:

The tall tower was originally known as Kent House, a 24 story tower block, and the most visible part of the old studio complex which also includes a significant area of land around the base of the tower, including the low rise buildings which can just be seen to the left of the tower, above the tree line.

Kent House, and the low rise buildings were until 2018, ITV’s London Studios, also known as the Southbank Television Studios. It was here that ITV made Good Morning Britain, Loose Women, Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway, the Jonathan Ross Show, along with a considerable number of shows for other channels, such as the Graham Norton Show and Have I Got News For You for the BBC. If you have watched ITV prior to 2018, chances are that you would have seen a programme filmed here on the south bank of the river.

The following photo shows the view of Kent House from Waterloo Bridge. The National Theatre is the building to the right.

ITV were intending to return to the south bank studios after refurbishment and development, however they made the decision to leave and sell the site, with their programmes such as Good Morning Britain now filmed at the old BBC Television Centre in White City.

The story of Kent House and the associated studio buildings dates back to the early 1970s when there were two independent television stations serving London. Thames Television operated from Monday to Friday, and from Friday evening to six on Monday mornings, London Weekend Television (LWT) would broadcast.

When LWT started broadcasting in 1968, they only had temporary studios in Wembley, and were in urgent need for custom built studios, which was even more important with the transition from black and white to colour TV.

LWT identified a block of land near the National Theatre on the south bank and proceeded to build the new studio complex, including Kent House. These opened in 1972 and became the hub for all LWT production. The benefit of a new build was that they became the most technically advanced colour TV studios in Europe at the time of opening.

The studio complex faces onto the walkway along the south bank of the river. The tower is at the rear of the complex, facing onto the street Upper Ground, with low rise buildings facing onto the river.

Studio buildings extend to the left of the above photo, with the block in the following photo up against the cafes, restaurants and shops at Gabriel’s Wharf which is further to the left.

The whole site will soon look very different.

ITV sold the studio complex in 2019, including Kent House, to the Japanese real estate company, Mitsubishi Estate, and plans have now been submitted for redevelopment.

Kent House and the entire studio complex will be demolished, and replaced by a 26 storey office building to the rear (Kent House has 24 floors), two lower rise blocks of 13 and 6 storeys facing on to the river.

What is a surprise is that the majority of the complex will be office space, with a capacity for up to 4,000 workers. Based on what normally happens to sites in such a prime location is conversion to apartment blocks, as is happening around the Shell Centre tower further west along the south bank. Whether the plan continues to be for offices after the work at home impact of the pandemic will be interesting to see.

The proposal also includes plans for some form of open space, the obligatory restaurants and some form of cultural space.

The view from Upper Ground:

The cafes, restaurants and shops at Gabriel’s Wharf are to the right of the two telephone boxes. Behind them are the low rise studio buildings.

Plans for the redevelopment of the area are still at an early stage, however Mitsubishi’s partner CO-RE are currently listing a 2026 date for completion of the project.

The following photo shows part of one of the old warehouses / offices at 58 Upper Ground, now part of the studio scenery stores.

To the left of 58 Upper Ground is the early 1970s studio complex at the base of Kent House:

The mock Tudor building is one of the few survivors from before post war redevelopment of the area.

ITV left the site in 2018, however the site still offers temporary office and studio space:

To the lower left of the Kent House tower, the studio complex can be seen at the rear. This is the western boundary of the studio complex. In the distance can just be seen the half roof of a covered walkway. This was where the audience attending a show would queue for entry. When I worked on the Southbank, it was common to see a long queue of people here in the late afternoon.

As shown in the above photo, there are frequently lorries parked around the base of the tower and studio area when the studios are in use.

The Southbank Conservation Area Statement prepared for Lambeth Council Planning states “The ITV tower is reasonably attractive but the lower buildings are of little architectural interest and the entrance forecourt is almost cluttered with waiting vehicles and delivery lorries”.

Personally, I think that this is a danger when looking at something only from a conservation perspective. The lorries at the base do add clutter to the scene, however they are there only because this is a working studio complex, which has added a diversity of activity and a busyness to Upper Ground.

The loss of a diverse range of activities when areas are transformed to a mix of expensive apartments, offices, hotels and chain restaurants, cafes and take-ways can really destroy an area.

Diversity of activity is essential in keeping a city alive.

The following photo shows the base of the tower and the lower levels of the studio complex. I love the way the tower looks as if it has been slotted over the lower levels, with the legs of the tower reaching down along the sides to the ground.

A full view of the Kent House tower from Upper Ground:

The next site is still on the south of the river, close to London Bridge Station and Tooley Street is:

Colechurch House

Colechurch House is a late 1960s office block on a relatively narrow strip of land between Tooley Street and Duke Street Hill. The main office building is lifted above ground level, and includes a walkway which provides access to the taxi waiting area for the station and London Bridge Street.

Colechurch House was designed by architect E G Chandler for the City of London. It was named after Peter de Colechurch who was responsible for the first stone London Bridge, the building of which was started in 1176 and completed in 1209.

The building and the freehold of the land is owned by Bridge House Estates, and on the 14th October, the City of London Corporation as Trustee of Bridge House Estates released a press statement that property owner CIT had purchased a lease of the building, and would be bringing forward proposals for redevelopment.

CIT’s proposals for the complete redevelopment of the site include replacing Colechurch House with a new office building ranging in height from 12 to 22 storeys, with the lowest height part of the building being at the London Bridge / Borough High Street end of the street. The highest part of the building was originally planned to be 32 storeys, however following a consultation process this has now been reduced to 22.

The new office block will be lifted off the street, with the area at ground level being public open space called the Park, which will be divided into a number of areas – Bridge Gate Square, Old London Bridge Park and St Olaf Square.

View of Colechurch House from the elevated walkway. The entrance to the office block is where the two lights can be seen.

The planning application was submitted at the end of 2020, a number of issues with the application were raised in a letter dated the 1st March 2021. Consideration of these and a final decision is still to be confirmed, however I expect the demolition and rebuild will go ahead within the next couple of years.

Across the river to Fleet Street now, to find the site of a much larger redevelopment:

Fleet Street and Salisbury Court

This is probably the larger of the three developments covered in this post, and it covers a significant frontage onto Fleet Street and to the rear within a block bounded by Salisbury Court and Whitefriars Street.

The redevelopment is for a new area which has been dubbed the “Justice Quarter” as it will include a number of new buildings that will house functions related to the law.

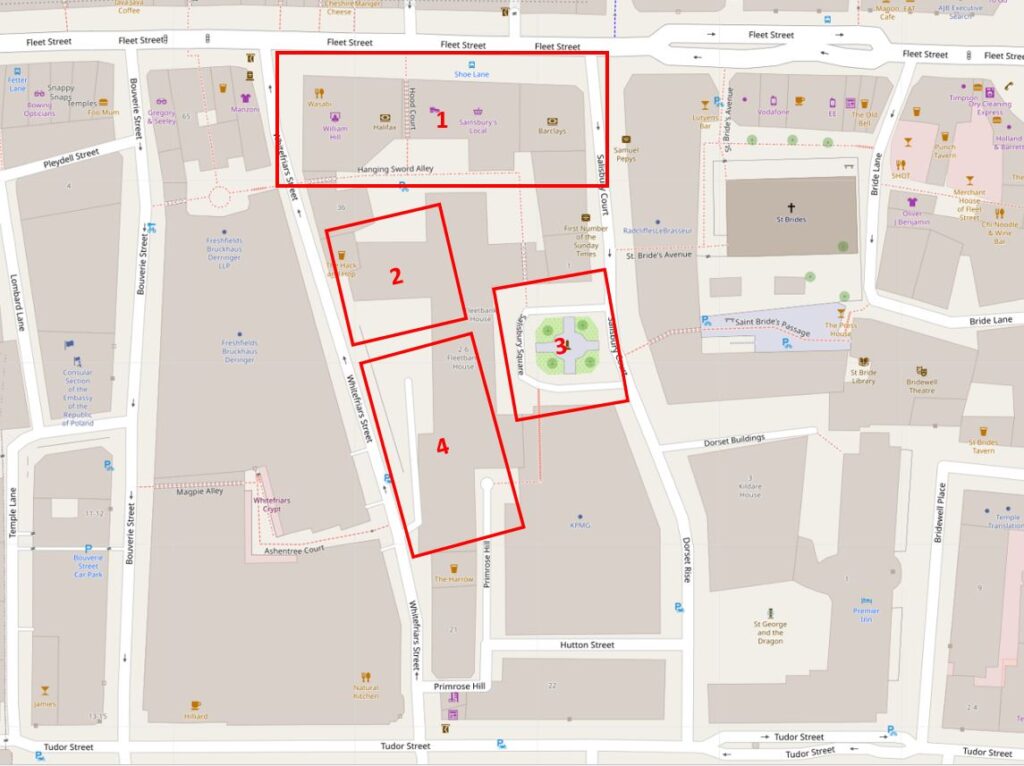

The following map shows the area to be redeveloped, and the new functions that will be located in the development (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

1 – New City of London Law Courts

2 – New headquarter building for the City of London Police

3 – Public space covering an area slightly larger than the current Salisbury Square

4 – New commercial / office space with, you may have guessed, space for restaurants, bars or cafes on the ground floor

The following photos walk through the area, starting from Salisbury Square, which is the green space within rectangle 3 in the above map.

This is the view across the square.

The building in the background is Fleetbank House, built between 1970 and 1975, a large building that has a lower section to the right, and also runs down Whitefriars Street, which is behind the building.

The obelisk in the centre of the square is a memorial to Robert Waithman, Lord Mayor of the City between 1823 and 1824. The memorial states that it was erected by his friends and fellow citizens.

To the right of the above photo, is the following brick building, 1 Salisbury Square:

The road to the right is Salisbury Court, running up to Fleet Street at the top.

Both Fleetbank House and 1 Salisbury Court have been granted a certificate of immunity by Historic England. This certificate states that the Secretary of State does not intend to list the buildings for a specific period of time – in the case of these buildings, up to July 2025.

If I have understood the proposals correctly, 1 Salisbury Square will be demolished and the area occupied will become part of the larger public space of Salisbury Square.

The following photo is a wider view across the square:

I am always amused by developers now and future impressions of proposed developments. If you look halfway down this page on the Salisbury Square Development website, there is a now and future picture where you can scroll between the two.

The now part of the photo was taken on a relatively grey day, with people milling about, or hurrying across the square. The proposed computer generated picture, shows the square at dusk, subtle lighting lights up the trees and the ground floor area of the new public space and there is not a cloud to be seen in the sky. Buildings frequently look their best with this form of lighting.

This type of comparison is all too common with the proposals for any new development.

A row of bollards line Salisbury Square:

Walking along Salisbury Court, up to Fleet Street. A relatively narrow street, the edge of 1 Salisbury Court is to the left of the photo:

8 Salisbury Court – again if I have understood the proposals correctly, this building will also be demolished, and the land become part of the new public space.

To the right of number 8, is a large brick building that covers number 2 to 7 Salisbury Court. This is Greenwood House.

The blue plaque states that the first number of the Sunday Times was edited at 4 Salisbury Court by Henry White on October 20th 1822.

The building dates from 1878, and was designed by the architect Alexander Peebles.

Between the ground and first floors, the building has some rather ornate terracotta carvings, and the land or building may have once belonged to the Vintners Company, as their arms with the three tuns can be seen on the wall between first floor windows.

2 to 7 Salisbury Court are Grade II listed, however a City of London notice cable tied to the iron railings outside the building state that a number of changes will be made:

i) Part demolition of 2-7 Salisbury Court Grade II listed;

ii) remodelling at roof level;

iii) formation of new facade to south elevation, and part new facade to west elevation;

iv) replacement fenestration;

v) new plant; and

v) associated internal alterations.

The two “v” bullets are directly from the notice, the final should I suspect be a vi.

Always hard to decode exactly what these planning notices mean, but I suspect it will be a new façade to replace the joining wall where number 8 has been demolished. Possible demolition of the internal structure of the building, with the wall facing Salisbury Court retained as a façade. A new roof and changes to the windows.

So some dramatic changes.

The view looking down Salisbury Court from the junction with Fleet Street:

On the corner of Salisbury Court and Fleet Street is 80 to 81 Fleet Street. A large corner building that was until recently a Barclays Bank. The building was originally, up to 1930, the home of the Daily Chronicle.

This corner building will also be demolished, and will form, along with the entire block along Fleet Street as shown in the above photo, the new City of London Law Courts.

The centre block in the following photo is Chronicle House, covering 72-78 Fleet Street. The building dates from 1924 and was designed and built by Hebert, Ellis & Clarke.

The building takes its name from being home to the newspaper, the News Chronicle. The building has also been granted immunity from listing by Historic England and the Secretary of State.

The following block is on the corner of Fleet Street and Whitefriars Street, and will also be demolished to become part of the Law Courts complex.

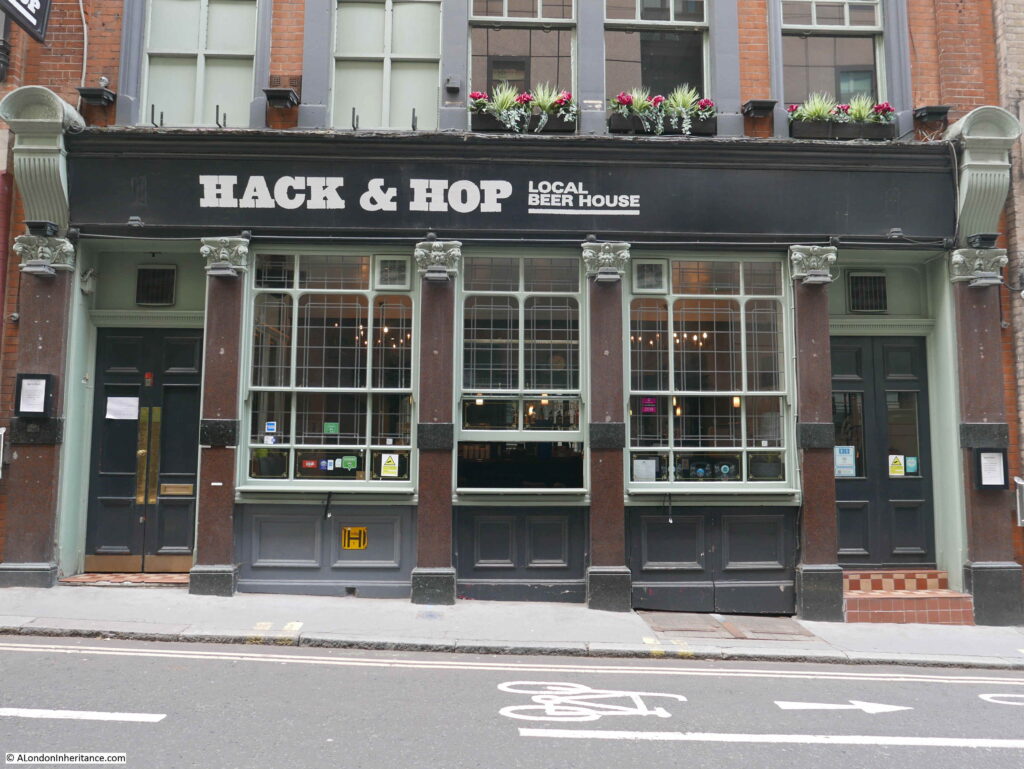

Walking down Whitefriars Street, and the following building is the Hack and Hop pub:

The Hack and Hop was originally the Coach and Horses, a pub that dates back to the mid 19th century. The earliest record I can find of the pub is a newspaper mention in the Morning Advertiser on the 25th November 1850, where there was an advert for a regular Monday evening meeting where a penny subscription would be collected for the London Copper-Plate Printers Benevolent Fund – a reminder of the long history of the area with the printing trade.

The buildings along this part of Whitefriars Street, including the Hack and Hop pub will be demolished and replaced by the new headquarters building for the City of London Police.

The new building will bring together police functions from a couple of existing buildings which have already been sold – Wood Street and Snow Hill police stations. The new building will have ten floors above ground with space for 1,000 police officers and civilian staff, with three levels below ground for specialist functions and parking.

Continuing on down Whitefriars Street, and we see the other side of Fleetbank House:

Fleetbank House will be demolished and replaced with a new office / commercial building, which is described as having a “lively frontage”. I suspect this means cafes, bars and restaurants.

The view looking up Whitefriars Street, with the grey walls of Fleetbank House.

The end of Fleetbank House in the above photo marks the southern limit of the new re-development of Whietfriars Street. The work to create the so called Justice Quarter will be one of the most significant developments along Fleet Street for a very long time.

The area off Fleet Street has a considerable amount of history which will require a dedicated post. Hanging Sword Alley passes through the space from Whitefriars Street to Salisbury Court. There is a memorial to journalist T.P. O’Connor along Fleet Street. Bradbury and Evans, one of Dickens publishers were located here. The Fleet water conduit was here until the Great Fire in 1666.

The whole block has a long association with the journalism and the publishing industry, which ended in 2009 when the French Press Agency left 72-78 Fleet Street (Chronicle House).

It is hard to avoid getting into a discussion about the good or bad points of any new development, and I have tried to avoid this in the above post, focusing instead on recording what may well disappear in the coming years.

There is much to consider regarding any change. The buildings lost, the new buildings, what the change brings to the overall area, architecture, impact on wider views, jobs, diversity of activity etc. etc.

There is also the issue of what then happens to the buildings where functions will move from. For example, one of the City of London courts that will move into the new Fleet Street building is the City of London Magistrates Court on the corner of Queen Victoria Street and Walbrook, shown in the following two photos:

A building in a very prime location.

Development often leads to further development as functions, businesses etc. shuffle their way around the City.

Three possible future demolitions and re-developments that will have a significant impact on their local area of London.

Further reading on these can be found at:

City of London Salisbury Square Development web site

City of London Consultation briefing for the Salisbury Square development

Save Britain’s Heritage petition to stop the demolition of 72 – 81 Fleet Street

Colechurch House development web site

Article with artist’s impression of new Colechurch House development

Article with artist’s impression of development on south bank replacing Kent House and Studios