My posts of last weekend covered some of the extensive damage suffered by the City of London during the war. Fortunately there were areas that escaped with only light, cosmetic damage and have also survived the considerable development in the intervening 70 years. Places remain where it is still possible to get an impression of what London was like as a city of narrow lanes.

The church of St Mary At Hill is best approached not by the road of the same name, but turn off the busy East Cheap / Great Tower Street and head down Lovat Lane. This is the scene which meets you.

Lovat Lane is a narrow lane that heads down to Lower Thames Street and retains the width of many of the city lanes prior to the war. Buildings face directly onto the lane and we can see the tower of St Mary at Hill which, unusually for a City church, still appears to be higher than the immediate surroundings.

The name Lovat Lane is recent. The lane was originally called Love Lane and was changed around 1939 to avoid confusion with the Love Lane further north off Wood Street. This change also appears to have justified the lane being included on maps. In the Bartholomew’s London Atlas for 1913, Love Lane is included in the index and referenced to the correct grid square in the map, however it is not shown. In the 1940 Bartholomew’s Atlas, the name has now been changed to Lovat Lane and is shown on the map. Various early references attribute the original name as being due to the frequenting of the lane by prostitutes, however this may be wrongly using the same source for the other Love Lane which Stow refers to as being “so-called of wantons”. The new name Lovat was chosen due to the quantity of salmon being delivered to Billingsgate Market from the fisheries of Lord Lovat.

As with many other City churches, a church has been recorded as being on the site since before the 12th century. The church was severely damaged in the 1666 Great Fire and then came under the rebuilding programme of City churches managed by Wren, however it was probably Wren’s assistant Robert Hooke who was responsible for much of the design and reconstruction of the church. The “At-Hill” part of the name is due to the church being located up the hill from Billingsgate and the downwards slope of Lovat Lane is one of the locations where the original topography of the City can still be seen with the streets sloping down from the higher ground down to the river.

Despite the central location of St. Mary, the church survived the blitz, although a fire in 1988 severely damaged the Victorian woodwork, the organ and the ceiling, however the interior has been superbly restored.

Before entering the church, walk past the church and look back up Lovat Lane, again we get a really good impression of what the narrow city lanes would have looked like. Remove the modern-day signage and add some dirt to the road surface and soot stain to the brick walls and we could have travelled back in time.

Although just as we walk back up to enter the church, the modern-day City intrudes:

The church prior to the Great Fire, in common with many other City churches of the time had a spire. These were made of wood and covered in lead. In 1479 the church of St. Mary at Hill paid “Christopher the Carpenter” 20 shillings to take down the spire and 53 shillings to rebuild using 800 boards, two loads of lead, nails and ironwork costing 14s 7d.

On entering the church we can see the following carved Resurrection Panel.

From the information sheet;

“The Last Judgement relief is a very unusual example of late 17th century English religious carving, and most likely dates from the 1670s. Its carver is unknown, but we do know that the prominent City mason Joshua Marshall was responsible for the rebuilding of the church in 1670-74: his workshop may have produced the relief. Exactly where the relief was originally positioned is uncertain; most likely it stood over the entrance to the parish burial ground and was brought inside in more recent times.

St. Mary-at-Hill’s relief is one of a small number of Last Judgement scenes carved in later 17th century London.”

We can now enter the main body of the church and a wide space opens up before us, surprising considering the external appearance from Lovat Lane:

The restoration following the 1988 fire created a very simple interior. The original box pews were lost and not replaced leaving a large open space from where we can look up and admire the interior of the roof, restored following the fire of 1988:

Again a surprise given the external appearance of the church from Lovat lane.

Again a surprise given the external appearance of the church from Lovat lane.

Within the church before the Great Fire was a large Rood, a cross or crucifix set above the entry to the chancel. In 1426 a new Rood was installed at St. Mary at Hill and cost £36, a very considerable sum at the time. A great stone arch was built to support the Rood, however in 1496 the arch required underpinning to support the weight and to achieve this the church procured three stays and a “forthright dog of iron” weighing 50 pounds.

At the same time the Rood was renovated and we can get an idea of what this must have looked like by the items that were included in the renovation:

– to the carver for making of three diadems, and of one of the Evangelists and for mending the Rood, the Cross, the Mary and John, the crown of thorns and all other faults

– paid to Underwood for painting and gilding of the Rood, the Cross, Mary and John, the four Evangelists and three diadems

It must have been a very impressive sight. The work was funded through a subscription being raised across the parish. Parishioners contributed a considerable sum towards the upkeep and decoration of their church. In 1487 a parishioner, Mistress Agnes Breten paid £27 to have a tabernacle of Our Lady painted and gilded. In 1519 a parishioner provided a large carved tablet to hang over the high altar at a cost of £20. Thirty years later at the time of the reformation the tablet had to be sold and only raised 4s 8d, a time that marked the end of the type of church decoration that had persisted from the medieval period.

Back towards the entrance is the magnificent organ, built by the London organ manufacturer William Hill in 1848. It is the largest surviving example of his early work and reputed to be one of the ten most important organs in the history of British organ building. William Hill worked for the organ builder Thomas Elliot from 1825 until Elliot’s death in 1832. He had married Elliot’s daughter so on his death he inherited the company. The Hill’s workshop was London-based in St. Pancras and was known for building organ’s of the highest quality, providing organs for many important locations including Birmingham Town Hall and York Minster. The business continued until 1916 when Hill and Son as the company was known amalgamated with another organ builder Norman and Beard of Norwich. The combined company of Hill, Norman & Beard diversified into cinema organs in addition to church organs, however the limited market for these specialist products resulted in the company closing in the 1970s.

The organ was restored following the fire of 1988 and rededicated in 2002.

The organ was restored following the fire of 1988 and rededicated in 2002.

The church has one more secret to reveal. Step through the side door and we are out into what remains of the churchyard. Totally enclosed on all sides and only accessible either through the church or through the small alley at the far end of the churchyard which leads through to the street of St. Mary-at-Hill.

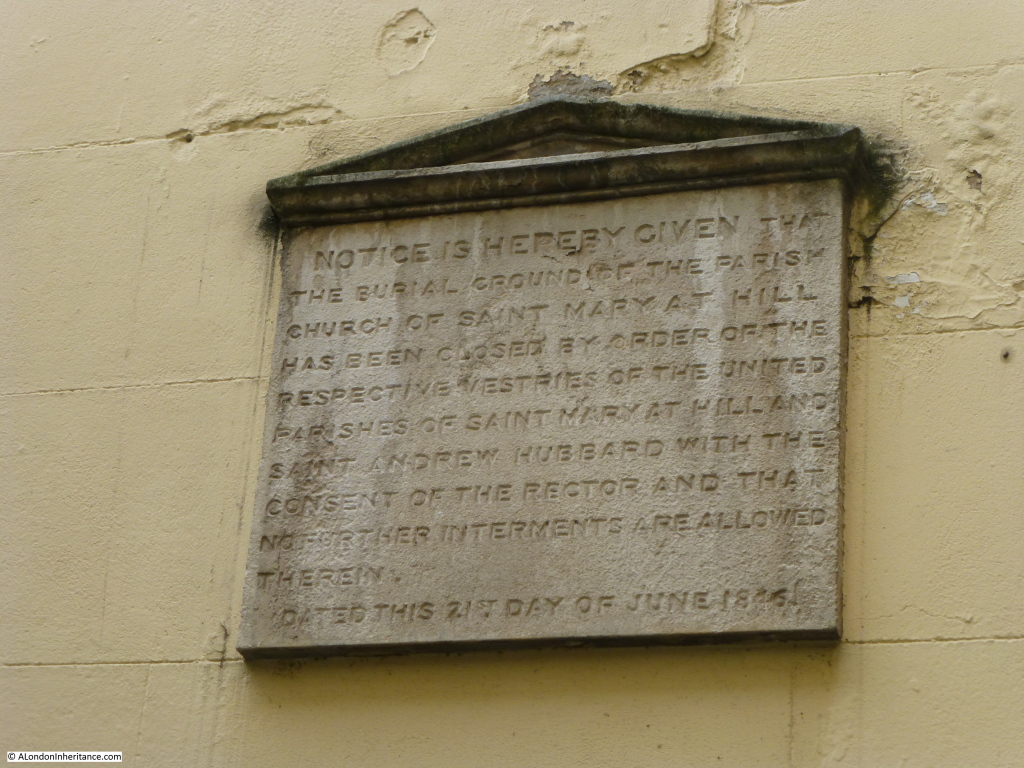

A plaque on the wall informs us that “the burial ground of the parish church of St. Mary-at-Hill has been closed by order of the respective vestries of the united parishes of St. Mary-at-Hill and Saint Andrew Hubbard with the consent of the rector and that no further interments are allowed therein – Dated this 21st day of June 1846.” Following closure, all human remains from the churchyard, vaults and crypts were removed and reburied in West Norwood cemetery.

A plaque on the wall informs us that “the burial ground of the parish church of St. Mary-at-Hill has been closed by order of the respective vestries of the united parishes of St. Mary-at-Hill and Saint Andrew Hubbard with the consent of the rector and that no further interments are allowed therein – Dated this 21st day of June 1846.” Following closure, all human remains from the churchyard, vaults and crypts were removed and reburied in West Norwood cemetery.

The reference to St Andrew Hubbard is an example of the consolidation of parishes after the 1666 Great Fire, The church of St Andrew Hubbard was not rebuilt and the parish integrated with that of St. Mary at Hill.

The reference to St Andrew Hubbard is an example of the consolidation of parishes after the 1666 Great Fire, The church of St Andrew Hubbard was not rebuilt and the parish integrated with that of St. Mary at Hill.

Looking back towards the doorway we can see, above the round window some of the original fabric exposed .

And at the end of the churchyard, one final look back before entering the short alley that takes us into the street of St. Mary at Hill.

With not too much imagination, Lovat Lane and St. Mary at Hill provide a glimpse of what the City of London was like when many of the City streets were lanes and churches stood tall above their surroundings. Highly recommended for a visit.

St. Mary at Hill is regularly opened by the Friends of City Churches

The sources I used to research this post are:

- The Old Churches Of London by Gerald Cobb published 1942

- Old Parish Life In London by Charles Pendrill published 1937

- Historic Streets of London by Lilian & Ashmore Russan published 1923

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878

- Bartholomew’s London Atlas, 1913 and 1940 editions