I love buildings where the design of the building indicates the activities carried out within the building. These buildings show a pride in the purpose for which the building was constructed. They are not the all too frequent bland architecture we see so much of today where almost any interchangeable activity could be carried on within. These buildings proudly call out why they are there. This week’s post is about one such building. I walked past the building earlier this year and took some photos on a rather grey day. This is the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine:

The origins of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine are in the London Docks, where a seamen’s hospital opened at the Royal Albert Dock in 1890. This would evolve into the London School of Tropical Medicine, also in the Royal Albert Dock, which opened in 1899.

In 1920 the school moved to Endsleigh Gardens, to the south of the Euston Road, and a couple of years later, a government report recommended the formal establishment of a school for tropical medicine by the University of London. This was confirmed by the grant of a Royal Charter in 1924 for the school as the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

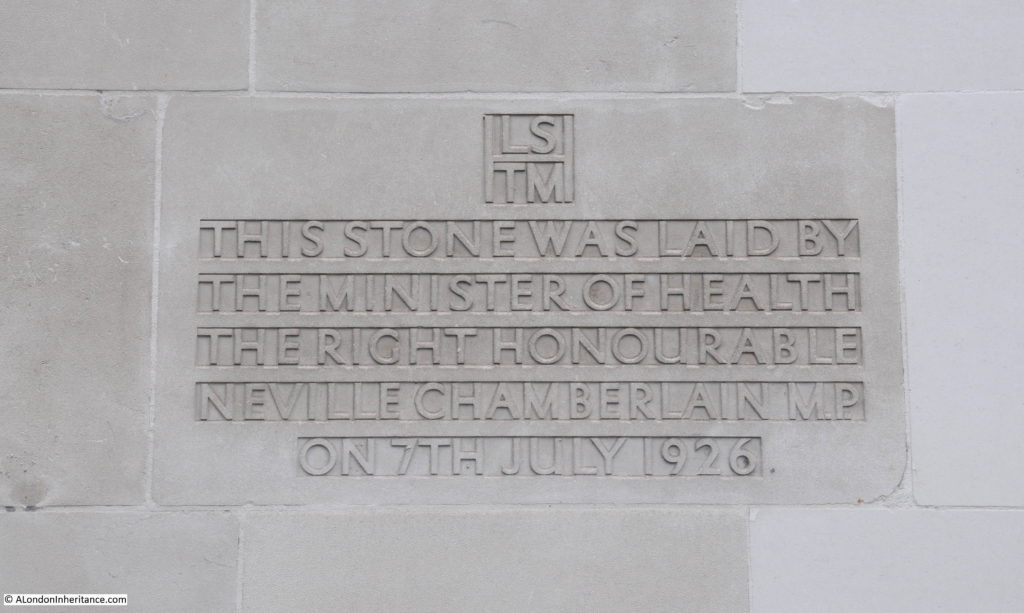

A site was found for the new school in Keppel Street, opposite the Senate House of the University of London and the foundation stone was laid in 1926 with the school being officially opened in 1929.

At first glance, the building looks like any other stone office block, but look closely and the building has some remarkable details.

The overall building is a steel frame with Portland Stone cladding. The main entrance to the building is in Keppel Street.

The door is raised above street level and reached by a a short flight of steps. Above the door is a carving of the school logo, Apollo and Artemis riding a chariot.

If you look above the door to the first floor, each of the windows has a small, ornamental balcony with a small metal frame. On either edge of the frame are gilded representations of the insects and animals that act as carriers of the diseases that the school was set-up to study, treat and eliminate.

A walk around the building provides a handy guide to the insects and animals you would not want to be bitten by:

The above is just a sample of the balconies. On reaching the corner of the building there is, in my opinion, one of the best street name signs in London:

As with the best design, these signs are very simple. but highly effective and lovely to look at. The signs look even better on a sunny day when the gold lettering glints in the sunlight.

The foundation stone was laid by Neville Chamberlain on the 7th July 1926.

Neville Chamberlain is probably better known for his attempts when Prime Minister to make peace agreements with Germany prior to the start of the last war, the Munich agreement with Hitler and the “peace in our time” words used after his return. Chamberlain had a long political career before becoming Prime Minister and for a time in the 1920s he was Minister of Health.

A newspaper report on the day after the foundation stone was laid provides background as to how the new building was funded. The report is titled “London School of Hygiene. Rockefeller Foundation’s Generosity”

“The Minister of Health (Mr Neville Chamberlain) yesterday laid the foundation stone of the new London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine at Malet Street, WC.

The guests were welcomed by Sir Alfred Mond, M.P. (Chairman of the Board of Management) who said it was during his term of office as Minister of Health that the trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation made their magnificent offer, providing a sum of two million dollars for the building and equipment of the new school. The purpose of the institution was of the highest importance to the people of this country and the population of the Empire, and indeed of humanity.

The University Grants Committee was giving £5000 a year towards the cost of immediate development, and the Rockefeller Trustees had assisted with a grant of £4000 a year towards the cost of maintenance until the new school was ready. About a year ago the Rockefeller Foundation substituted for their original undertaking a promise to pay a sum of £460,000, that being the value in sterling at the time of their entering into agreement to provide the original sum. By this action they cancelled the loss due to the rise in the cost of sterling, which would otherwise have meant a diminution in the value of the gift of some £50,000.

Before laying the foundation stone, Mr. Neville Chamberlain said that ceremony marked the commencement of a building which was the result of a combination of the two great English speaking nations, and which, in all human probability, was destined to be famous thereafter as the greatest centre in the world of research and of instruction in one of the most beneficent of all the activities of the human race. The school would have the latest types of apparatus and equipment, and it would contain a notable feature in the shape of a great teaching museum, which would show in a graphic form the subjects which were being taught, and the symptoms of the diseases.

The following cablegram was sent to the Trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation:- On the day of the laying of the foundation stone of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the American and British flags fly side by side at the dawn of a new era of preventative medicine. The Minister of Health, Mr Neville Chamberlain, sends cordial greeting, and renewed acknowledgements to the Trustees of the Rockefeller Foundation.”

The London School Of Hygiene And Tropical Medicine was opened on the 18th July 1929 by the Prince of Wales. Reports of the opening were carried in the majority of the following day’s newspapers. There were hardly any reports of the actual opening ceremony, the reports focused on the Prince meeting the workers who had constructed the building:

“The Prince and Workmen – Pledges Their Good Health In Beer.

When the Prince of Wales opened the new building of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Gower Street, he pledged good health in beer to two hundred workmen who have been engaged on the building.

The workmen were entertained to lunch by Lord Melchett in a marquee in a courtyard of the school, and the Prince, after the opening ceremony, walked down to the marquee to see them. As he entered they stood and cheered him for several minutes.

Then the foreman said ‘ We will drink the Prince’s health’ and the two hundred workmen held up their glasses of beer and shouted ‘good luck’ and good health’.

The Prince himself then raised a glass of beer high above his shoulder, and shouted ‘Here is the very best to you too. Thank you, thank you,’ and drank the beer.

The workmen afterwards sang ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow, and then the Prince asked they go on with their lunch. ‘Give us a speech, prince’ cried one of the men as he turned to go. He halted, turned round, and said ‘Good-bye, men, I am very glad to have seen you all. Good -bye.”

Above the upper floor windows, are the names of men (this is the 1920s and the names were chosen by committee, probably also all men), who had been influential in the development of public hygiene and tropical medicine.

In the photo above are:

Edmund Parkes, a 19th century physician who as a result of the dreadful medical conditions of the Crimean War, developed Army Medical Services and in 1863 published the Manual of Practical Hygiene.

William Leishman, an army physician who died in 1926, not long before the opening of the school. He worked on a typhoid vaccine whilst at the Army Medical School at Netley, alongside Southampton Water.

Timothy Lewis, a 19th century Welsh surgeon who worked in India on several tropical diseases.

Further along are Lister and Pasteur:

Joseph Lister was a 19th century surgeon whose work in the prevention of infections during surgery, the use of sterile techniques, carbolic acid to dress wounds, aimed to reduce the significant post operative dangers from infection in the 19th century.

Louis Pasteur was a 19th century French chemist who worked in the fields of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurisation, the technique which carries Pasteur’s name in which food stuffs are treated with mild amounts of heat to kill pathogens.

Further along are the pathologist and surgeon John Simon, and Patrick Manson who was the founder of the field of tropical medicine.

Lemuel Shattuck from Boston in the United States was responsible for the introduction of the registration of births, marriages and deaths. Perhaps not an immediate name to associate with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, however when this type of information is correctly and fully recorded across a population, its use in the development of public health strategies is invaluable.

Edwin Chadwick was a 19th century social reformer. His work reforming the poor Laws and in improvement of public sanitation and public health were initially resisted, however in 1847 he was on a committee of inquiry into sanitary conditions in London and a later outbreak of cholera supported the recommendations he had made whilst serving on the committee.

Above the side entrance in Malet Street are three further names. Johann Frank was a German physician, Max von Pettenkoffer, also German, worked to further public hygiene, clean water and hygienic disposal of sewage. Hermann Biggs was an American who worked in the field of infection control.

I have only covered 12 of the names around the building. There are 23 in total. The website of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine provides detail on 22 of the names, and strangely does not include Louis Pasteur.

Who would have known that a walk around Gower, Keppel and Malet Streets would provide a history lesson in the development of public hygiene and health, and the fight against tropical diseases.

The exterior of the building is much the same as when first built, however there has been development of the building internally and extensions over what were internal courtyards. The importance of the building is such that it is Grade II listed.

The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine continues to perform important work in teaching and research and their building proudly advertises these activities to anyone who looks up.

And I still think the building has one of the best street signs in London.

I concur heartily about the street signs. About 40 years ago I used to go past this building on my way to work and often admired the detail I could see from the bus windows. I especially like the font used over the doorway. Such a graceful and unassuming building.

On the days when I’m working in London (usually three days a week) I walk past this building and the SOAS building and I love them. They lift my mood with the intriguing details. Thanks for a thorough overview!

Like Stella-Maria I used to walk past this building on the Mallet Street side (normally). I had noticed some of the details, but not all demonstrated in this fascinating post. Again very grateful for this post, and I’m looking forward to my next walk past (probably on Tuesday) when I can have another good look.

Thank you for a fascinating article. Some of the names are so well-known, but I suspect this building is keeping the other names alive. And I particularly loved the detail of the usual suspects on the balconies!

Really interesting that the School of Trop.H was originally in the Royal Albert docks. It is a lovely building but I never noticed the delicate decoration detail before.

I hope that John Snow, the Soho physician who made the link between the spread of cholera and water contamination, is one of the names on the building. (He does have a pub named after him.) It was such an important discovery.

Incidentally, Edwin Chadwick was also known for his punitive regimes in the workhouse, such as separation of husbands and wives, and mothers and children.