There are three photos in my father’s collection that I have not been able to identify. They were labelled “Sans Walk area”. Sans Walk is in Clerkenwell, and the first photo shows what appears to be an empty shell of a building, probably damaged during the war.

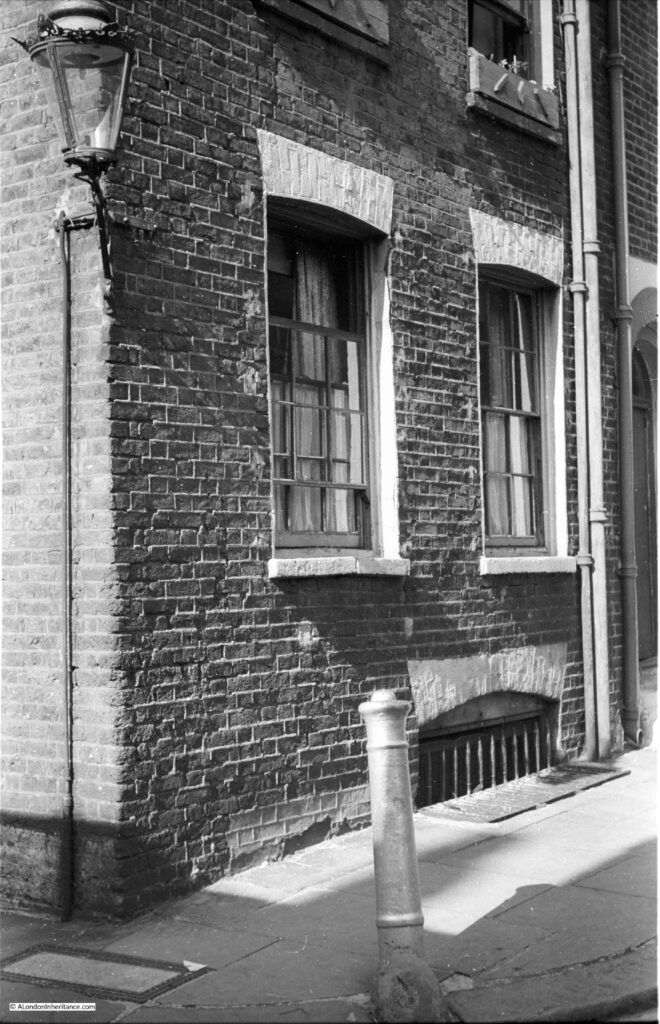

The second photo shows a corner house, in good condition and still occupied, with a lovely street lamp on the corner of the building:

The third and final photo shows part of a terrace of houses, with a streetlamp and bollards in the foreground.

No street names, or any other identifiable features to help locate the photos.

I thought if I walked the area around Sans Walk, I should be able to identify some of the locations. I had no idea whether the houses in the photos had been restored or demolished, but armed with printed copies of the photos I set off to walk the area on an early Autumn day.

Although I could not find the locations of the photos, what I did discover was an area packed full of history, and that once formed the edge of London as the city gradually expanded to the north.

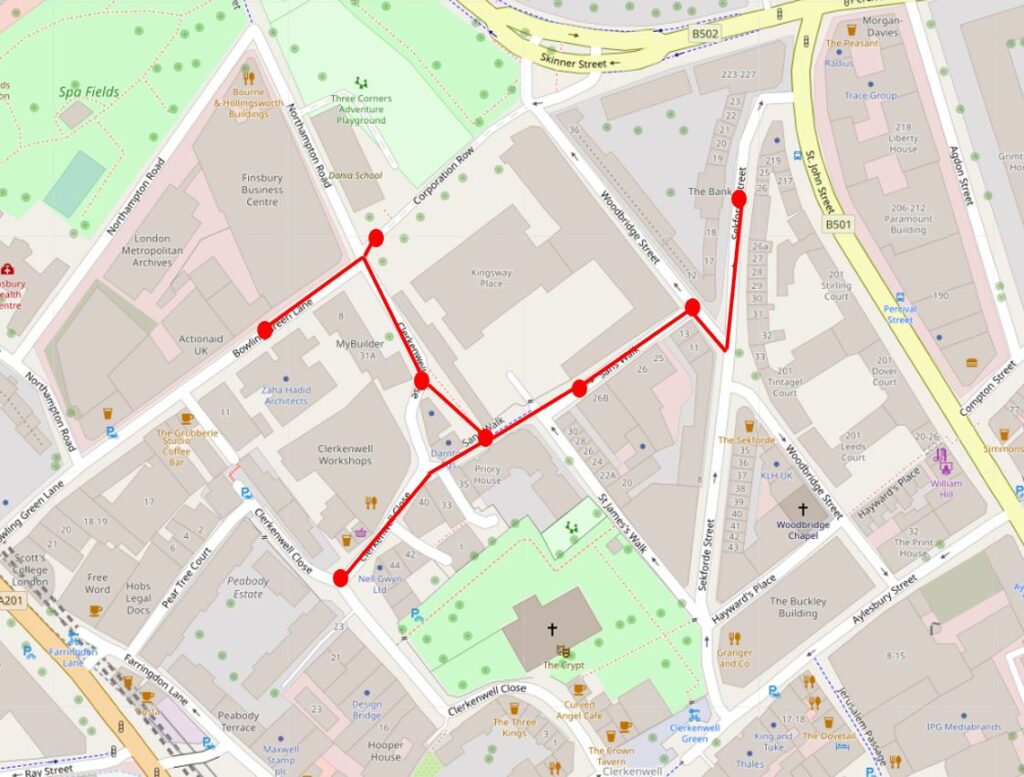

The following map shows the places covered in the rest of the post (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

Sans Walk is the nearly horizontal street in the centre of the map. I did walk the rest of the streets around Sans Walk, but this post was getting rather long with just the stops shown.

I started in Clerkenwell Close, opposite the Horse Shoe pub, a very traditional pub that probably dates back to the 18th century. The earliest written records I could find date to 1824 when a newspaper report referred to an inquest into a suicide which was held in the Horse Shoe.

This area of Clerkenwell is full of narrow streets. Some new buildings intrude, but many 18th and 19th century buildings survive, along with warehouses and factories from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Looking east along Clerkenwell Close:

Clerkenwell Close is a strange street as it consists of a number of branches. Starting at Clerkenwell Green, it runs north-west, up to Pear Tree Court and the Clerkenwell Close Peabody Estate, with the branch I am walking along turning off and running up to Bowling Green Lane and Corporation Row. At one point the street runs parallel to a pedestrian alley, both called Clerkenwell Close, and indicative of how the area has developed as large warehouses replaced earlier streets, alley and buildings.

New buildings had been added, but they are generally at the same height as the existing buildings, so despite the architectural and material changes, they blend in. Providing they are in keeping with the scale of the area, and there is a justification to replace rather than restore the original building, it is good to have new buildings. The streets in the area have buildings from the last few centuries and 21st century additions are part of the continuous development of London.

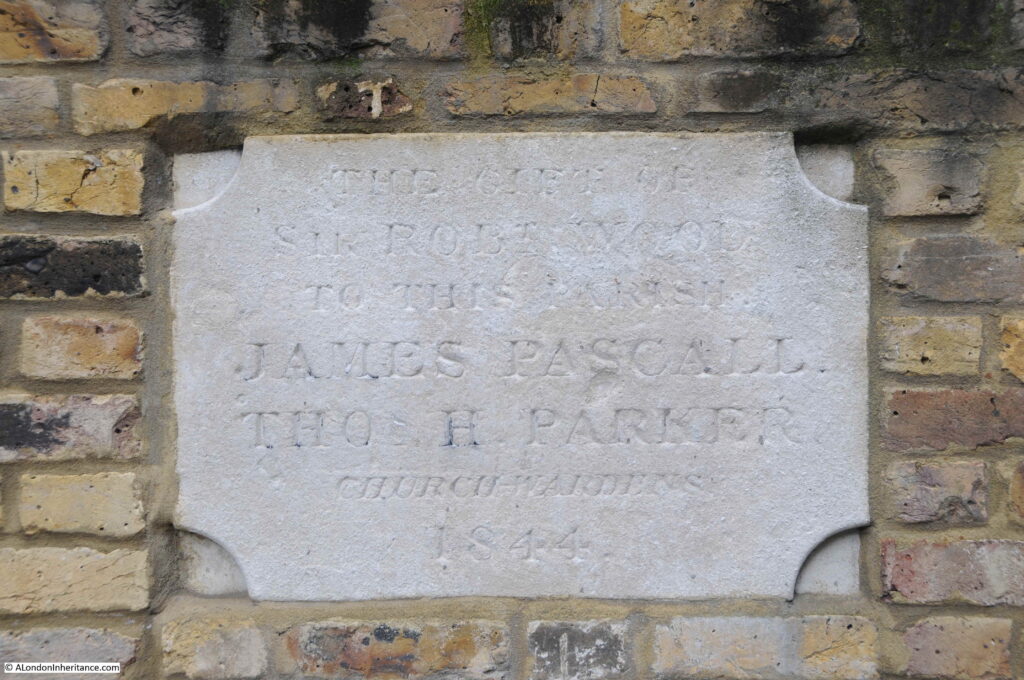

The above building was built on the corner of the playground of a Victorian school. The curving wall at street level retains a plaque recording the gift of Sir Robert Wood to the parish in 1844. I suspect this refers to the land:

We are still in Clerkenwell Close, and the following building tells of the late 19th century expansion of London schools and the London School Board.

The London School Board was responsible for the development of many of the large, brick, late 19th century schools that can still be found across London. As well as their construction, the London School Board was also responsible for their operation, and the supply of all the goods and materials needed to fit out, and keep a school running.

The Board consolidated the process of standardisation and supply, and one of the methods used was large central warehouses. The buildings in Clerkenwell Close were built between 1895 and 1897 as warehouses for school furniture, stationery and needlework supplies.

The growth in the volume of space needed grew in the early 20th century, and in 1920 an extra floor was added to the top of the Stationery and Needlework warehouse on the right of the above photo, and this addition is still visible in the change of brick colour from red/orange to a brown brick for the 20th century addition of the top floor.

In the above photo, the furniture store was on the left, and the Stationery and Needlework departments were on the right, and these functions are still recorded in stone, above the doors.

The initials at the top are those of the London School Board.

One of the schools that the warehouse would have supplied is directly opposite:

The school was the Hugh Myddelton School, built by the London School Board in 1893 and with the distinction of being the only London School Board school opened by a member of the Royal family after it was opened by the Prince of Wales in December 1893.

Such was the importance of the visit of the Prince of Wales that the London School Board allocated £100 towards preparations for the visit, which caused some consternation as the money was thought better spent on education.

In his opening speech, the Prince of Wales said that the London School Board had contributed to a “marked advance in education, diminution in crime and an undoubted increase in general intelligence”.

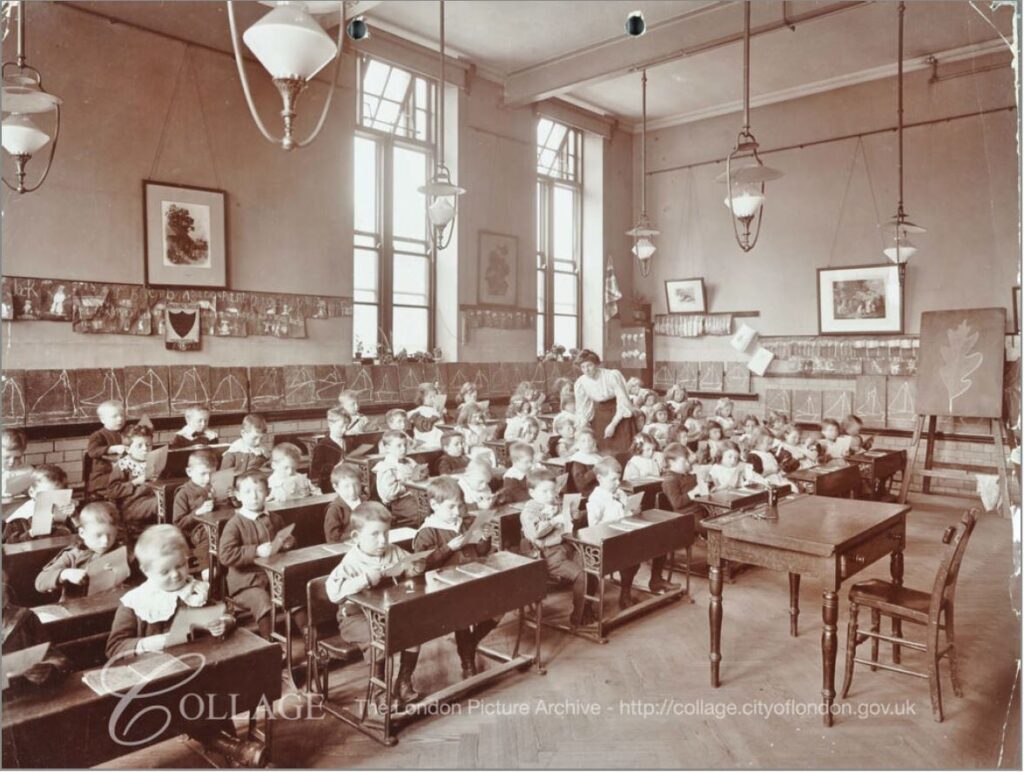

Lesson in the Hugh Myddleton School in 1906:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0208_3943

Drill in the open area outside the school, also 1906:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0208_68_4984

When opened, the school was the largest and most expensive built by the London School Board. The school had a number of special departments, including the Hugh Myddleton School for the Deaf. The site on which the school stands has an unusual history.

From 1845, the space occupied by the school had been the site of the Middlesex House of Detention, built as a short stay prison due to overcrowding in other prisons, the Middlesex House of Detention was demolished in 1886.

Some of the reception cells of the prison were in the basement, and these survived the demolition of the main building and were incorporated in the basement of the Hugh Myddelton School, and are presumably still there.

The school closed in 1971, was a Further Education College for the next couple of decades before being sold for development into flats and offices in 1999.

The site of the school, when occupied by the Middlesex House of Detention was the site of a bomb explosion in December 1867 reported extensively as the Fenian Outrage in the newspapers of the time.

This took place at the perimeter wall of the prison which ran along the northern edge of the site, in Corporation Street:

The Fenians was another name for the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an organisation formed in the 1850s to fight for an independent, democratic Ireland.

The bomb was an attempt to free Ricard O’Sullivan Burke and Joseph Casey who had been arrested earlier regarding Burke’s attempts to purchase arms and ammunition in Birmingham, and a previous attempt to free a prisoner in transit, when a guard had been killed.

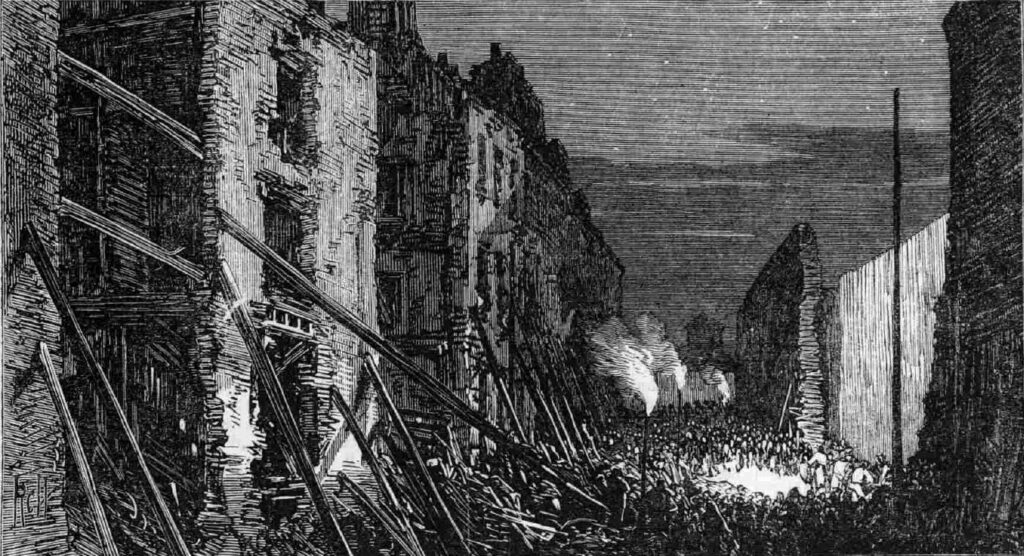

The view along Corporation Row in the immediate aftermath of the explosion:

The Illustrated London News carried the following report of the explosion:

“The whole neighbourhood of Clerkenwell was startled at a quarter to four on Friday afternoon by an explosion, which resembled an earthquake. The houses were shaken violently, the windows in many cases were broken, and in some instances persons were thrown to the ground by the violence of the concussion. The scene of the explosion proved to be the wall of the House of Detention, opposite Corporation-row, some sixty feet of which were knocked down, and it was not long before the discovery was made that numerous persons were seriously, and some fatally injured, and that the calamity had been wilfully caused. It was at once attributed to the Fenians, the motive alleged being a desire to rescue Burke and Casey, who are confined in the prison, and facts which have since come to light show that this theory is the correct one.

The clearest account of what actually took place is given by a boy about thirteen years of age, named John Abbott, who is now in St Batholomew’s Hospital, happily not very much hurt.

This youth who lived in Corporation-row, says that at about a quarter to four o’clock he was standing at Mr Young’s door, No 5, when he saw a large barrel close to the wall of the prison, and a man leave the barrel and cross the road.

Shortly afterwards the man returned with a long squib in each hand. One of these he gave to some boys who were playing in the street, and the other he thrust into the barrel. One of the boys was smoking and he handed the man a light, which the man applied to the squib. The man stayed a short time until he saw the squib began to burn, and then he ran away. A policeman ran after him, and when the policeman arrived opposite No 5, the thing went off.

The boy saw no more after that, as he himself was covered in bricks and mortar. The man, he says, was dressed something like a gentleman. He had on a brown overcoat and black hat, and had light hair and whiskers. He should know him again if he saw him.

There was a white cloth over the barrel, which was black, and when the man returned with the squib he partly uncovered the barrel, but did not wholly remove the cloth. There were several men and women in the street at the time, and children playing. Three little boys were standing near the barrel at the time. Some of the people ran after the man who lighted the squib.

The effects of the explosion were soon visible in all directions. The windows of the prison itself, of coarse glass more than a quarter of an inch thick, were to a large extent broken, and the side of the building immediately facing the outer wall in which the breach was made, and about 150 feet from it, bears the marks of the bricks which were hurled against it by the explosion. The wall surrounding the prison is about 25 feet high, 2 feet 3 inches thick at the bottom, and about 14 inches thick at the top.

As to the number of persons injured it was impossible for some hours to learn anything satisfactory. It was found, however, that something like fifty at least had been hurt, and that two or three were killed. Thirty six of the sufferers were removed to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, where three died in the course of the evening, and six to the Royal Free Hospital in Gray’s Inn Road. Of the wounded some were mere infants, and the husband of a women, who has since died of injuries she sustained, lies in St Bartholomew’s; shockingly bruised and prostrated. Others are missing”.

In the following days, 12 were confirmed to have died in the explosion, with very many injuries.

A number of Fenian sympathisers were arrested, but after trial only one, Michael Barrett, was found guilty, and was sentenced to death. Barrett was the last person to be publically hung outside Newgate Prison.

The scene in Corporation Row after the explosion. A temporary wall has been erected to plug the gap caused by the explosion, and the walls of the opposite houses are being held up with timber supports.

On a quiet autumn day in 2020 it is hard to imagine the explosion and devastation in Corporation Row.

As well as the Hugh Myddleton School built on the site of the prison, there is another closed school near by. Parts of the wall surrounding the playground and one of the entrances for infants can be seen in front of the recent building that now occupies part of the playground space.

This is Bowling Green Lane School, built in 1874:

Another London Board School, part of the site was originally a parish cemetery, along with housing and a tavern.

When the Hugh Myddleton School opened, Bowling Green Lane School became the junior school for the Hugh Myddleton.

Having built and run many schools in the later part of the 19th century, the London School Board would become part of the London County Council when the authority took over responsibilities for education across London.

A rather nice London County Council coat of arms can still be seen on the side of the school facing the street.

Bowling Green Lane school closed in 1970, but continued to provide additional space for Islington Green Secondary School until 1982 when it was converted into a range of business spaces, and today, a sign adjacent to the Girls and Infants entrance confirms that Zaha Hadid Architects now occupy the old school.

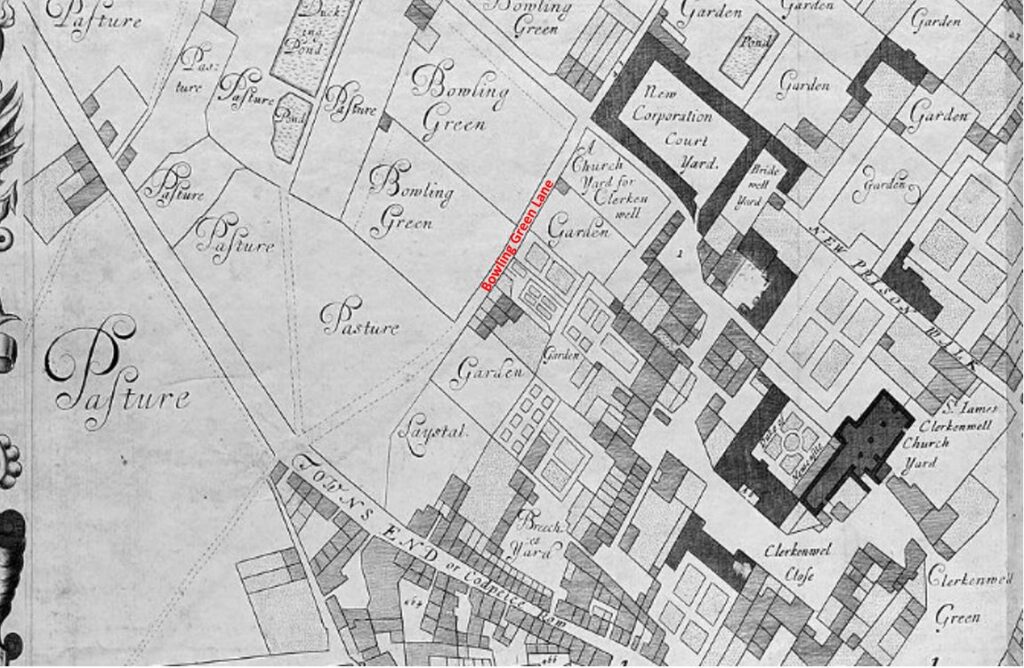

The name of the school is after Bowling Green Lane, the street that runs in front of the school. This is both an old street and name and is named after the Bowling Greens that once occupied the land to the north of the street as shown in this extract from Ogilby and Morgan’s map of London published in 1677:

For many years, Bowling Green Lane and Corporation Row were the northern edge of this part of London, with open space on the northern side of the streets.

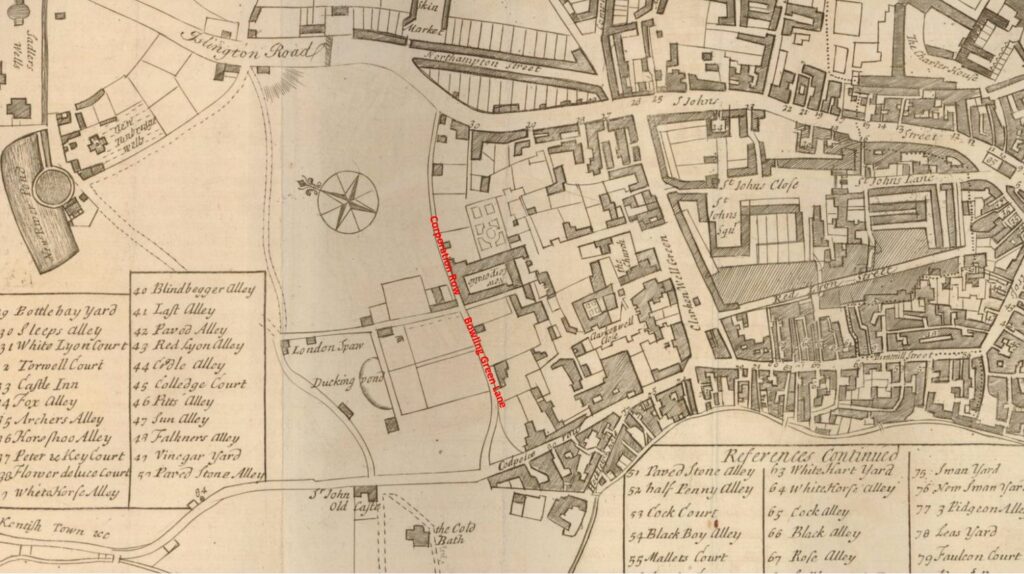

The following map extract is from a map produced in 1755 for Stowe’s survey of London. The orientation is rather strange as north is to the left, east is at the top of the map.

The built areas of Clerkenwell are to the right (south) and open space to the left (north) until we come to the New River Head.

Hugh Myddleton was the driving force behind the construction of the New River and round pond at New River Head, and the large new London School Board school was named after him.

Sadler’s Wells were just north of New River Head and the open space between Sadler’s Wells and Clerkenwell was often a dangerous place for those returning in the dark from entertainments – see my post on Sadler’s Wells.

I now reached Sans Walk, the street that was apparently the centre for the three photos.

Sans Walk appears to have been in existence at the time of the Middlesex House of Detention, but seems to have gone by the name of Short’s Buildings – the name of a terrace of buildings on the southern edge of the street.

The name Sans Walk seems to have come into use by 1893 and the name comes from Edward Sans, the oldest member of the parish vestry at the time.

In the western side of Sans Walk, there are new buildings on the southern edge and the old Hugh Myddleton School on the northern edge of the street:

Ornate, carved name of the school, high up on the wall to the left of the building.

The initials of the London School Board are also prominently displayed on the right of the school building:

The eastern stretch of Sans Walk – I could not match any of the buildings in the street with those shown in my father’s photos.

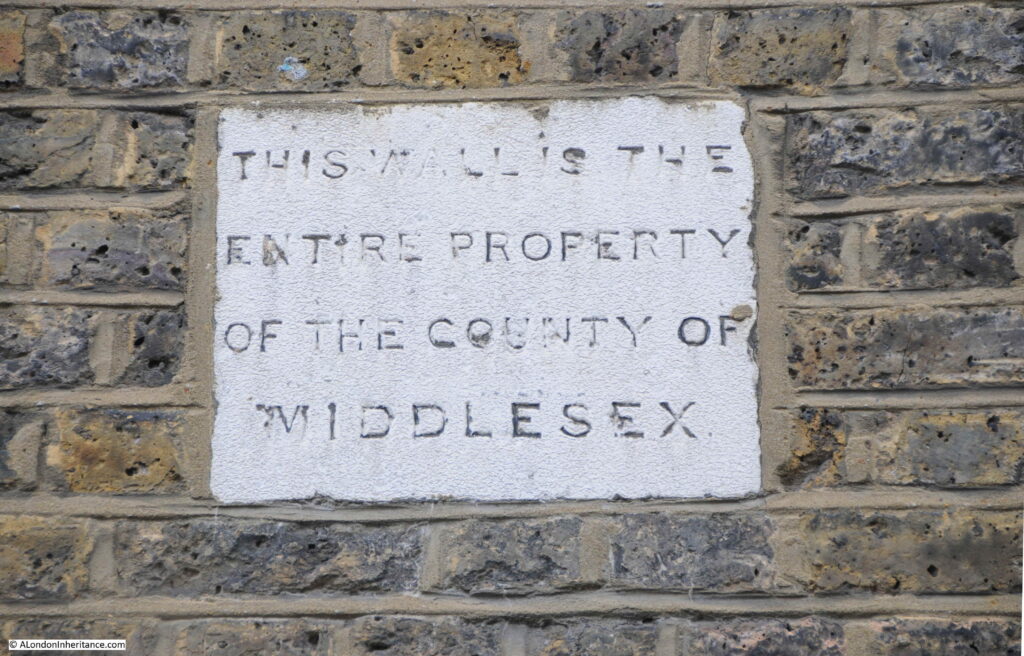

On the side wall of the house at the eastern end of Sans Walk is this plaque making clear that the entire wall is the property of the County of Middlesex. No idea if that applies to the rest of the house behind the wall, or just the wall.

Looking down Sans Walk from the east.

The building on the left does look like a restored version of one of the terrace of houses in the first photo, however the location is completely wrong. the house above is only a single house on the end of a very different terrace, and there is a road passing immediately in front of the house, with Sans Walk on the right.

At the end of Sans Walk is Woodbridge Street. I could not find any houses that matched the photos.

Running along the opposite side of the houses to Woodbridge Street is Sekforde Street, lined with early terrace houses, but again nothing that matched my father’s photos.

Half way along the street is an interesting building. painted white, that stands out from the terrace of houses on either side.

This is the former head office of the Finsbury Bank for Savings.

The Finsbury Bank for Savings opened in August 1816 at St. John’s Square, Clerkenwell Green. Formed to provide a service for small traders, labourers etc.

The bank moved premises to the building in Sekforde Street shown in the photo above in April 1841 after being built for the bank during the previous year.

Although the bank was intended for customers with limited savings, it was used by many more affluent customers, including the author Charles Dickens.

The Finsbury Bank for Savings went through a series of mergers, eventually becoming part of TSB, which in turn was taken over by Lloyds Bank.

I failed in the aim of the walk, to find the locations of my father’s photos around Sans Walk, although one of the aims of searching for these locations is to explore the surrounding area, and there was plenty to be found around Sans Walk.

The schools and warehouses of the London School Board, a 19th century bomb planted by the Fenians, the northward limit of Clerkenwell in the 18th century and streets that record lost bowling greens and one of London’s early saving banks – all within a short walk.

London is always best explored on foot and almost every street tells a story.

Excellent!

Fascinating reading and thoroughly enjoyable. Had no idea the Myddelton family had been so philanthropic for generations. The attention to detail, photos and background history make it even more interesting.

The grammar on the Sans Walk plaque always amused me. Middlesex must have been a poor county if the wall was all (the entire property) that they owned! Who owned the rest of the county, I wonder? 🙂

Very interesting, thanks. The 1954 OS map shows a dense network of old streets between Corporation Row and Myddleton Street, the main ones being Meredith Street, Skinner Street and Whiskin Street. There is a building marked as an engineering works the the heart of this labyrinth. Despite emerging unscathed from the Blitz, the area was almost completely cleared within the next decade. It may just be my impression, but Clerkenwell seems suffered more not-obviously-necessary clearance than most inner London boroughs. A retrospective of this or similar Clerkenwell quarters would make a fascinating sequel post.

Very interesting. An area I grew up in. Thank you.

I think I’ve found the location of the third of your father’s three photos, mainly thanks to the three bollards. In this 1952 large scale OS map the bollards are marked as ‘Posts’, just above the wording ‘SANS WALK’: https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=19&lat=51.52428&lon=-0.10596&layers=173&b=1. Hence the houses – now demolished – were 13 & 14 Sans Walk. This is confirmed by a 1948 photo from Collage: https://bit.ly/35PJjQZ.

Correct! StreetView even shows three (replacement) bollards in roughly the same place, and a fire hydrant in the pavement opposite (outside the new-build).

Yes, you are right. I was looking to see if the houses remained, rather than the evidence in the street. There is a hydrant sign on the wall in the third photo and looking at Streetview, there is still a fire hydrant in the pavement. Thanks

I think I’ve also found the location of the second photo. The shadows in the third photo show that the sun was in the south-west. It seems reasonable to assume that all three photos were taken on the same day at around the same time. If so, the shadows in the second photo imply that the house in that photo was on the northern side of a street that ran south-west to north-east. On the 1952 map to which I linked in my previous post the only possible corner houses that fit the bill near Sans Walk seem to be 10 & 13 St James’s Row. In the second photo, note the shadow of what appears to be a chimney pot. I don’t think any of the nearby houses have a chimney pot that could throw its shadow on the pavement outside 13 St James’s Row. However, a chimney pot on 2 Newcastle Row might well throw a shadow in that position. Hence I think the house in the photo is 10 St James’s Row. I can’t find a photo of the north side of St James’s Row. However, on the left hand side of this photo looking down Newcastle Row you can see the corner with St James’s Row: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publications/pubid-1286/images/fig17.jpg. Notice the leaning bollard and the streetlamp attached to the wall.

Although I don’t live in London, a fair few of my ancestors did and I enjoy your blog very much – so thank you!

Just an idea ….. you maybe able to find the location of picture number three by tracing the location of the water hydrant on the wall.

London Firebrigade inspect the hydrants every year and so would have a database to reference. Might be worth contacting their museum to see if they have archives records for the hydrant markers.

Jan, if you are thinking that the marker can be indentified by the number thereupon, this is not the case. The number “4” is the diameter of the water main in inches – very important to know when operating the high-power pump of your fire appliance to avoid collapsing the water main by excess suction. The Jul 2008 Google Street View shows a modern yellow replacement marker at the location (as identified by Malcolm) giving the same information in millimetres – 100. (The marker is missing in all subsequent GSVs).

Very enjoyable and interesting. Does anything remain of the original walls that were around at the time of the Fenian bomb? Prison or houses opposite?

The third picture was taken from Clerkenwell Close looking into Sans Walk. There’s a tree in your picture of Clerkenwell Close that is in roughly the position from where the shot was taken.

Yes, you are right, thanks. I checked on streetview and there is a fire hydrant in the pavement, and a hydrant sign on the wall in the third photo which really confirms the location. I was looking to see if the houses remained rather than the evidence in the street. Thanks

I think the view of the terrace with the bollards is taken from the edge of Clerkenwell Close, looking across Sans Walk. The old houses are gone, replaced with modern flats and the tree is, of course, much bigger now but quite possible to have grown to that height in 70 years. If you look at the paving stones and the slight tilt in the middle of the alley, it makes sense. And the bollards, while not the same, are in the same position but the lamp removed. I love this part of London.

Annie – thank, you are right. I was looking to see if the houses remained and was ignoring the evidence in the street. There is a hydrant sign on the wall of the old houses, and the fire hydrant remains today in the pavement to confirm the location.

I understand that subterranian cells from the House of Detention still exist and were incorporated in a private museum, since bancrupt,in the 1990s

They were reputed to be haunted – see ‘Walking Haunted London’ by Richard Jones.

Another fascinating post, thank you

Bingo! Here’s a photo showing the location of the first house with the lamp. Down at the bottom left, the same pale line of bricks, the same leaning bollard. Newcastle Row. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp28-39

Now flats, road still curves.

Phew….

Excellent article. It’s an interesting area to walk around and your post really brings the history of into the light. Re: the writing class, I’m glad to say that by the time I went to school (in a much more westerly London borough) Jack’s activities had changed to accompanying Jill to fetch pails of water from higher ground!

Hi Don, I missed that when I was checking the post. Have changed the photo and will drop the London Metropolitan Archives an e-mail as the photo came from their online collection.

I spent a day walking around there looking for all the places mentioned in George Gissing’s excellent book, The Nether World (1889) which is almost entirely set in that area. Thank you for your detailed research on the various parts of London you explore. I love reading your blog.

The first photo is of №s 2-4 Warden’s Place, off Clerkenwell Close, with the bomb site of № 1 to the left.

https://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/view-item?i=63070

shows the same houses in 1952 (the title and description are incorrect).

https://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/view-item?i=63084

was taken from the same spot as your father’s, but in the opposite direction, in 1952.

https://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/view-item?i=63072

shows the rear of the three house from Clerkenwell Green (not from Farringdon Road)

It appears from your father’s photo that № 4 was less seriously damaged than №s 2 and 3. There are two photos on Collage dated 1982 showing the rear view of № 4 and vacant plots where №s 2 and 3 had stood.

A fascinating post. I hate to be pedantic and this is not a criticism, but just for clarity: It’s not London School Board. The correct name of the organisation was The School Board For London. If you look at the photo you’ve published above, of the SBL plaque on the Hugh Myddelton School, they have even shown the word FOR on the plaque. Anyway, an excellent post. Let’s have more please! Thank you.

Another fascinating read, Was a bit surprised by the school chalk board in PHL_02_0208_83_2543 I’m sure different terminology would be used these days!!!

I have been to few meetings with tech start ups in some of those streets and it was interesting to read about their history.

Keep up the good work

I found the photograph of the writing lesson very interesting. As a left hander myself I always notice when someone is ‘cack-handed’. The boy at the desk at the front on his own is obviously left handed, which I find interesting as most left-handers, particularly at this time, would have been forced to use their right hand, as was my mother-in-law in the 1920s. I was taught italic handwriting with a left handers fountain pen with a sloping nib in 1956.

I also, as a left hander, looked for other left handers in that photo. I did not think there would be any because, as you say, they were forced to write with their right hands. I was forced to write with my right hand until I went to a State Primary school and they allowed me my left. This was in the 50s though. Pretty traumatic when you are having a hard enough time managing to write anything at all!

Great bit of reading.

Fantastic info and photos as usual

thank you

regards

Joyce

Yes, you could visit the remains of the old prison under the school. It was also used as an air raid shelter during the war and had station numbers on the walls so that people knew where to congregate. The entrance was through an old school entrance.

didn’t get a post on sunday but saw there was one. I’m not on social media radar so it’s email or nothing.

even though rotherhithe not of huge interest per se I always enjoy your enthusiasm and research especially as I’m an ex picture editor and an ex-Londoner.

perhaps it was just a blip.

regards Kay Rowley

My grandmother lived on the top floor of the end house in Sans Walk, on the junction of Sans Walk and St James Walk, the photos of the buikdings bought back lots of marvellous memories. thank you for taking me back to my childhood and beautiful memories

My great grandfather was 11 months old , 1881 census at 15 St.James Walk, Clerkenwell, Middlesex.