As well as a large collection of photographs, my father also had a large collection of books about London which he started collecting during the early 1940’s as a young teenager. Most of the books are factual accounts about different aspects of London and London’s history, however some of these are plans for major projects being proposed at the time as well as reconstruction plans for London after the war.

I will be covering many of these books in my blog over the coming months and I want to start with a fascinating document which proposes a major change to the River Thames and has echoes in the Thames today.

The book is “Tideless Thames in Future London” by J.H.O. Bunge which was published by the Thames Barrage Association in 1944.

There had been proposals for many years for a Thames Barrage with the aim of stopping the tides and providing central London with a river without any tides. The proposal compares the tides and mud flats along the Thames with other cities where damming rivers had produced effectively a slow moving lake with no tides. Boston in the USA where the 1906 damming of the Charles River had provided for the city “better health, water sports, riverside parks with the famous Boston orchestra’s loudspeaker concerts in the open are the results of this dam”. The book compares Boston with the mud banks along Putney, Fulham and Hammersmith.

The barrage would also have provided other functions which at the time were becoming critical due to the expected growth in traffic after the war, for example the provision of a road and rail bridge across the river.

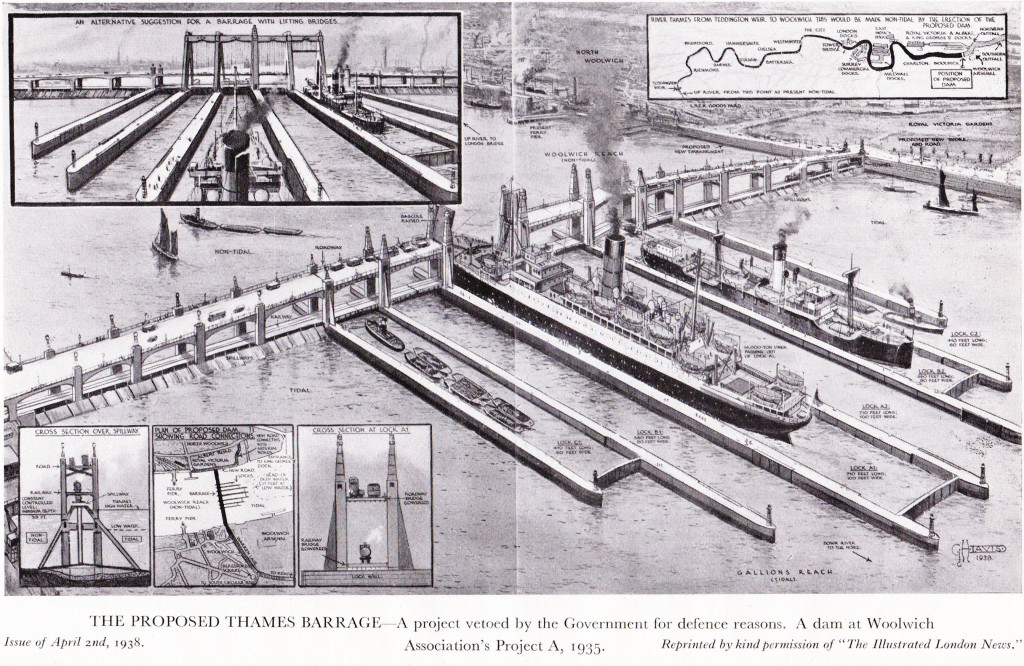

So what would the proposed barrage have looked like? The following picture from the book shows the proposed barrage at Woolwich.

The locks within the barrage were critical to the design as at the time the annual tonnage of shipping to London’s docks was well over 50 million. London was still the largest port in the world.

Note the road and rail bridges built into the overall design.

Had this been built (and it was estimated at a cost of £4.5 million and could be built in 18 months “if efficiently organised” which seems somewhat optimistic) London today would not have any tides with the river transformed into a slow moving lake.

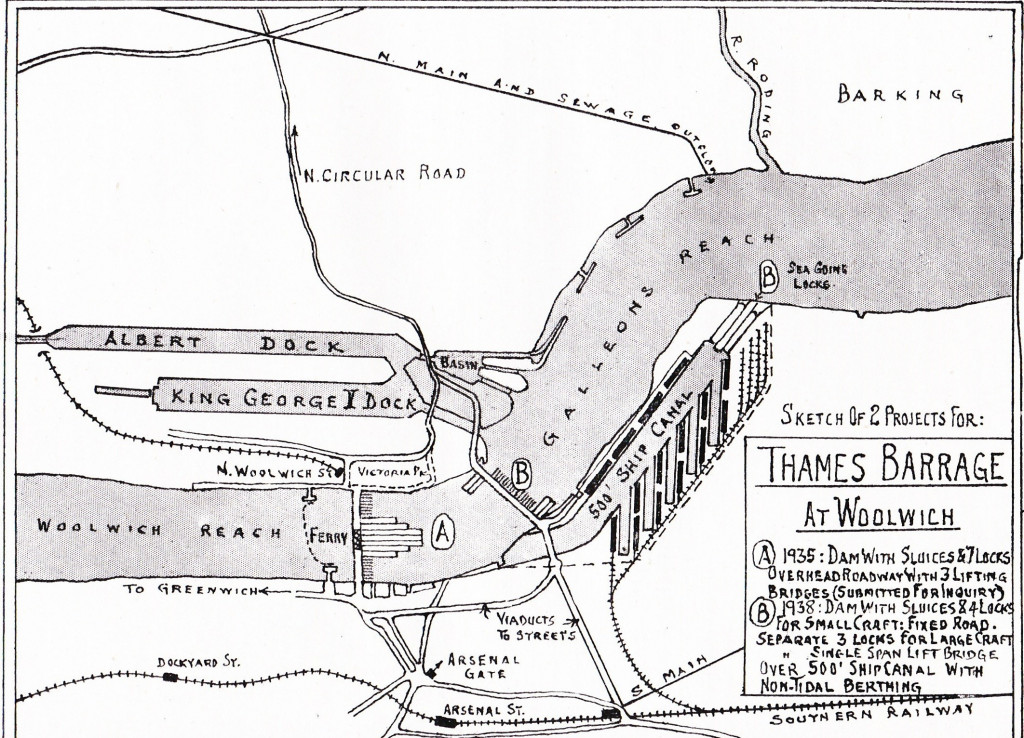

The location of the proposed barrage is shown in the following map:

Note the integration with the North Circular Road. There is a clear parallel with the river crossing at Dartford and the M25. The first Dartford tunnel was built in 1963, the second in 1980 and the Queen Elizabeth II bridge which is the clear successor to the bridge proposed by the barrage which opened in 1991.

There were many objections to the proposed barrage and the government of the day was strongly against the proposal. There was a debate on the subject of the barrage in 1937 in the House of Lords where a number of objections were raised. The usual concerns about the costs of building and then the costs of running the proposed barrage, and also:

– the impact on the hygiene of the river without a twice daily “flushing” of the river by the tides

– the impact on shipping of having to pass through the locks. Remember at this time, the docks in central London were very busy. The Port of London Authority stated that in 1936 there were “43,000 ships and 463,000 craft of one kind” passing through the river at the proposed location of the barrage and these would have to pass through the locks.

Stand on the banks of the Thames at Woolwich now, and it seems incredible to imagine that volume of shipping passing along the river in front of you.

The Port of London Authority objections also show the difficulty in planning for large scale projects for the future. I wonder if they could have imagined what would have happened to the London docks after the introduction of containerisation and the resulting increase in the size of shipping and the move of the major port facilities out of central London to Tilbury, Felixstowe and Southampton.

Personally I am very pleased that the barrage was not built. The Thames without tides would have taken much of the life out of the river that forms the core of London and was the reason why the city came to be built here in the first place.

The mud banks to me are not to be hidden. They maintain a link to the history of London. Stand on the banks of the Thames at low tide at almost any point on it’s course through London and you will see old bricks and stones that could have come from the buildings that once lined the river. The wooden stumps of old jetties still protrude above the mud along with the stone cobbles of old slipways.

The tides also continue London’s connection with the sea. Despite being in a city with ever growing towers of glass and steel, the daily rise and fall of the river maintains a natural connection.

Some ideas from the Thames Barrage Association did get built though, but in a very different form. The extension of the North Circular across the river via a bridge across the barrage can been seen replicated in the M25 and the crossings at Dartford, and the barrage itself turned into something not to keep the water in central London, rather to keep the water out of central London in the form of the Thames Barrier.

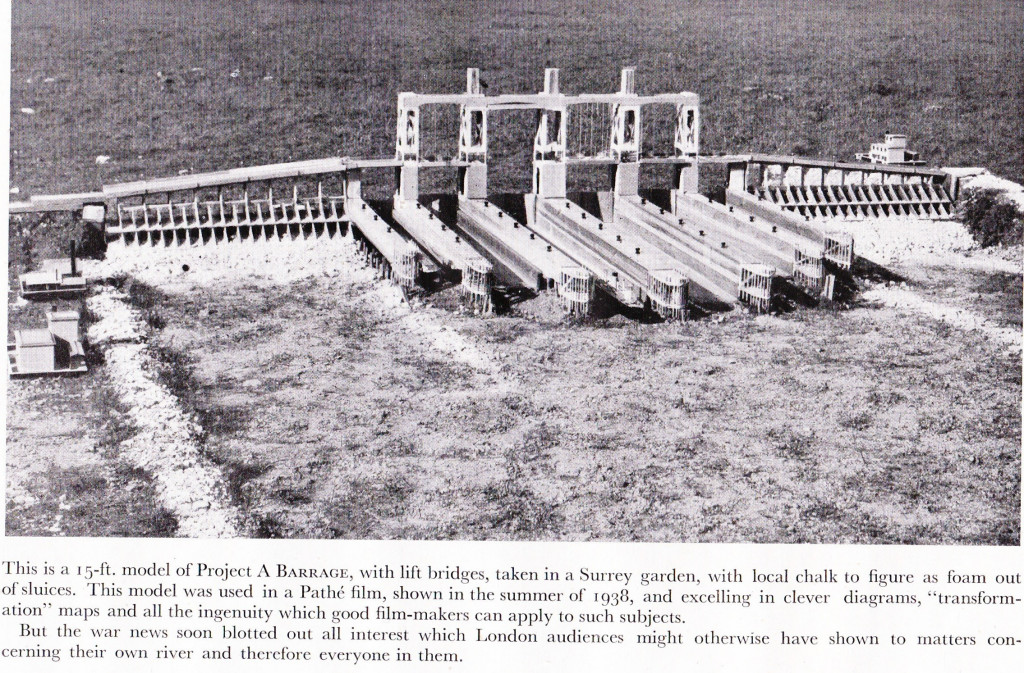

The book includes a photo of a model of what the barrage may have looked like:

Note the comments about the impact of the war, and the book published in 1944 was the last gasp of the proposal. The war did though allow the Thames Barrage Association to raise some additional justifications for building the barrage, including the difficulty that the London Fire Brigade had during the war with getting water from the Thames during low tides to fight the fires caused by the bombing.

I wonder what the Thames Barrage Association would have thought of the Thames Barrier?

This is the Thames Barrier as seen from the bank at the Visitor Centre. At the time it was an ordinary high tide and the river was only about 6 inches below the river walkway. Really shows how much the barrier is needed. Inside the gates at the left is a walkway with along the wall, a profile of the River Thames from Thames Head to Sea Reach:

When you stand beside a river it looks flat. The profile really demonstrates the fall of the Thames as it drops a total of 105m from head to sea.

Reading “Tideless Thames in Future London” provided a fascinating snapshot of how London, the Docks and River Thames were viewed at the time. When the volume of shipping on the Thames and at the London Docks was expected only to grow, and London was expected to continue to be one of the world’s major ports.