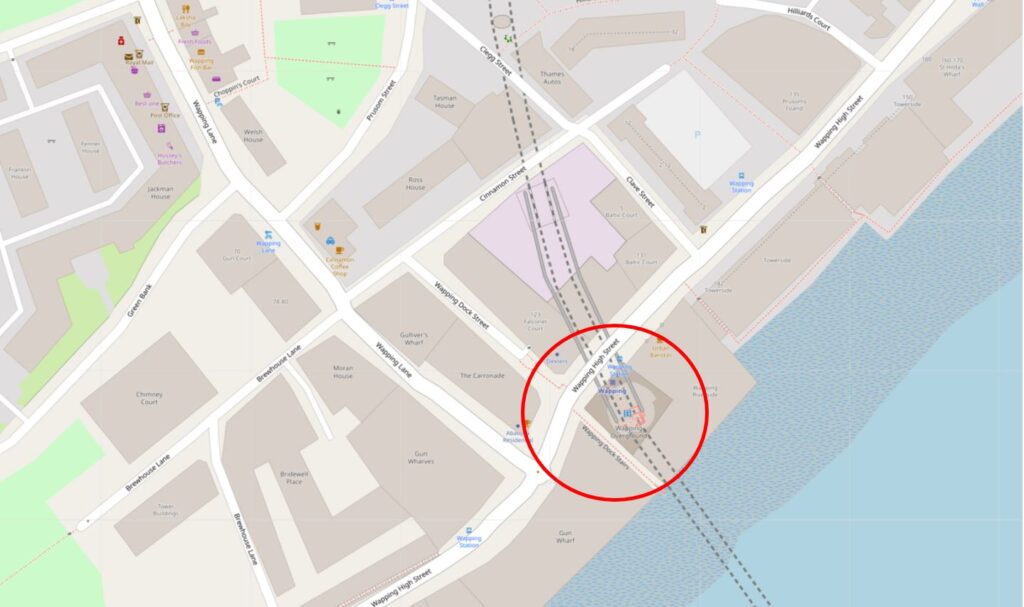

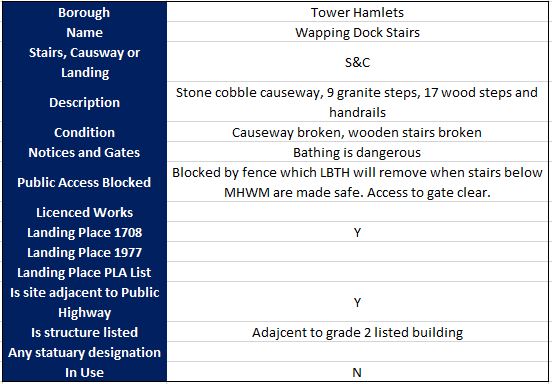

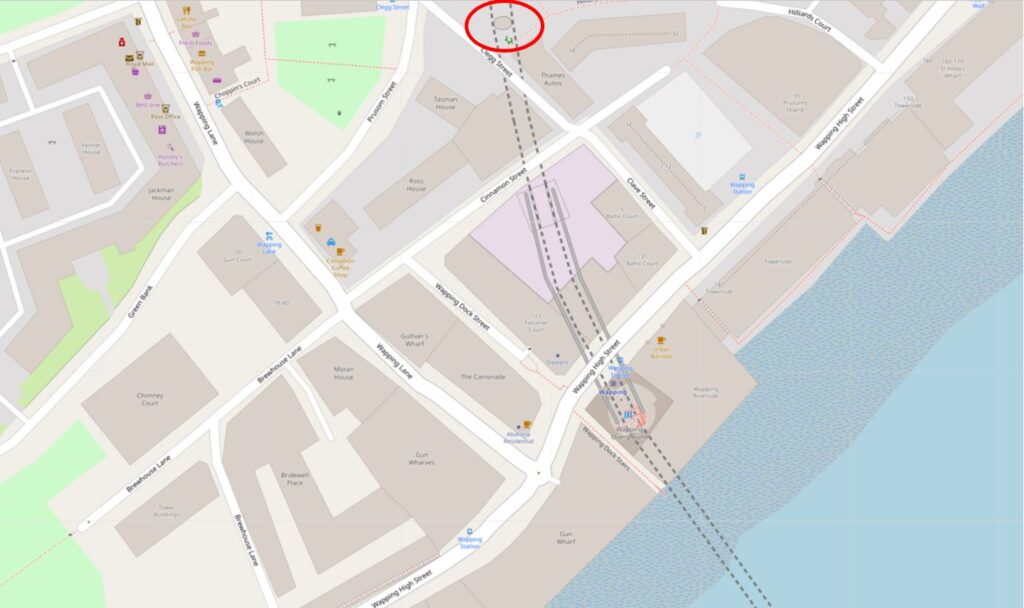

Firstly, a quick apology for an error in last week’s post. I had confused the size of the floors in the Swan pub, at Wapping Dock Stairs. The newspaper article I referred to stated they were 30 feet square on each floor, which I stated would have been just over 5 feet on each side (30 square foot, rather than 30 feet on each side of a floor), so a much larger room, and a reminder to me to read through my posts a couple of times before sending.

Thanks to those who let me know about the error.

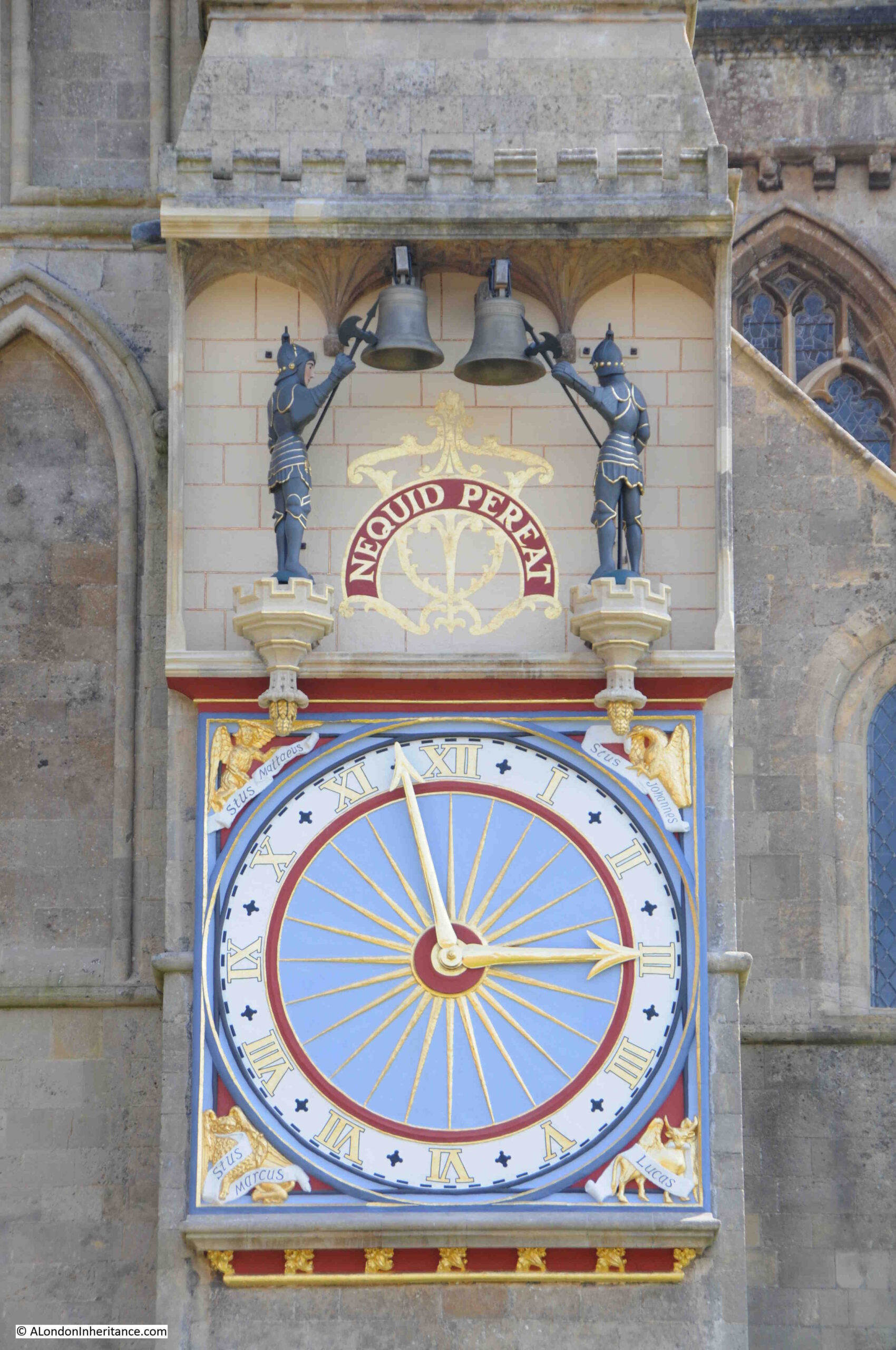

For this Sunday’s post (and after reading through three times), a return to discover some of the fascinating stories told by the plaques that can be seen whilst walking around the City of London, starting with;

The Samaritans – St Stephen Walbrook

There is a blue City of London plaque on the side of St Stephen Walbrook, where St. Stephen’s Row heads along the rear of the Mansion House, arrowed in the following photo:

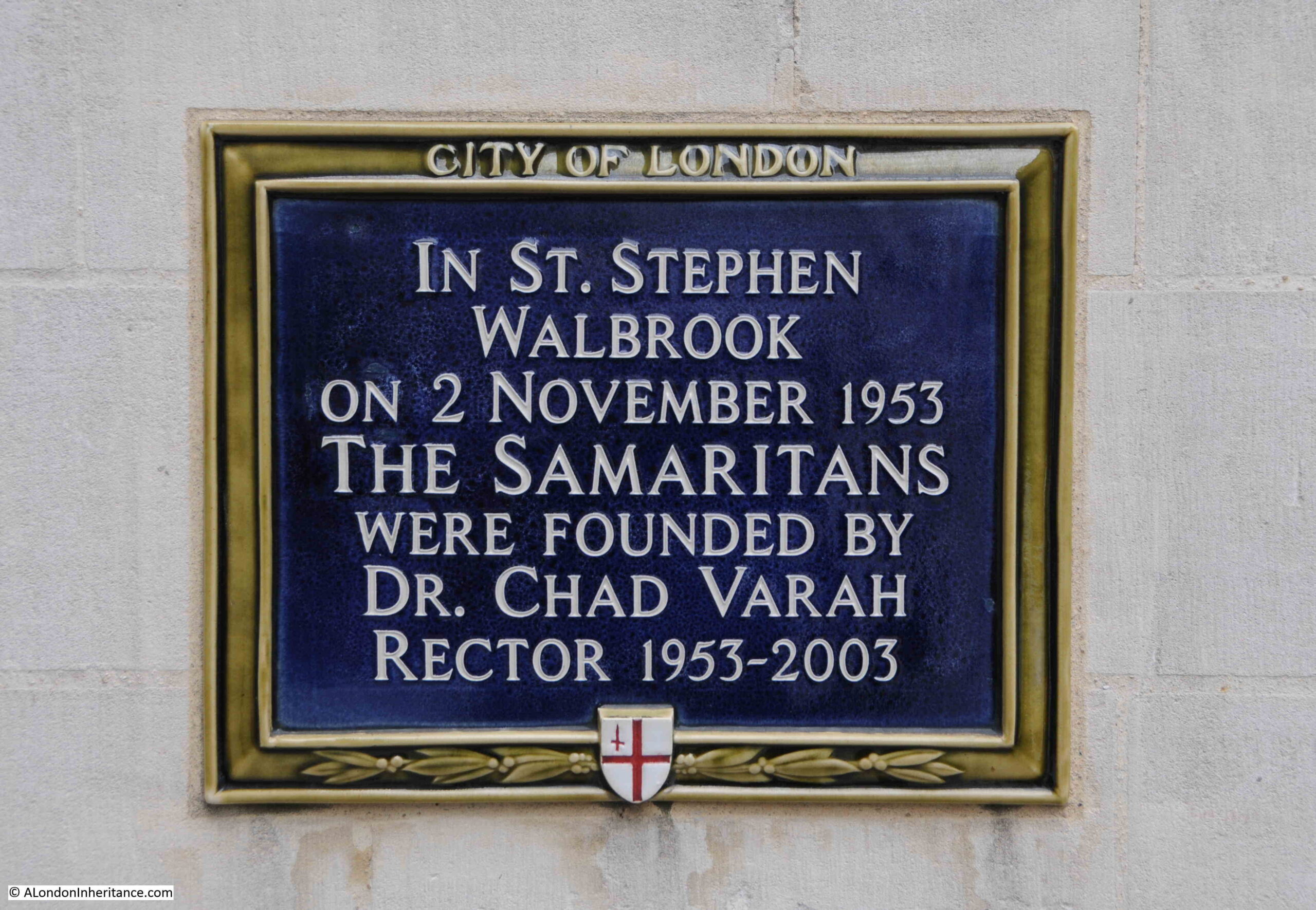

The plaque records that the Samaritans were founded in the church in 1953 by the rector, Chad Varah:

Edward Chad Varah. to give him his full name, was born on the 12th of November 1911 in the Lincolnshire village of Barton-on-Humber. He was the eldest of nine children and the name he would be known by came from St Chad, founder of the parish.

He did not intend to follow his father into the church, however he was persuaded by his godfather, Archbishop Hine.

In the early 1950s, he was based at Clapham Junction, carrying out house visits, and working as the chaplain of St John’s hospital, Battersea, however despite these activities, his stipend was very low, with hardly any money available for his work, and just enough to pay for a secretary. To help generate additional income, he took on a second career as a scriptwriter for children’s comics.

Varah had very liberal views for the time, particularly for a person of the church. He was a strong believe in sex education, and believed this was key for poorly educated young people.

His believe in the importance of sex education, and willingness to listen to people, to provide advice, and eventually to start the Samaritans may have come from an event in 1935 when Varah was an assistant curate in Lincoln. He had to conduct his first funeral which was for a 13 year old girl who had taken her own life. The girl had started her period, however without knowing what was really happening she feared she had a sexually transmitted disease which would result in a slow, painful and shameful death.

His lack of money whilst working in Clapham Junction, along with the responsibility of a parish, prevented any formal development of a system of help for those at risk of suicide, of which there was an average of three a day in London in the early 1950s.

Help came when he was offered the living of St Stephen Walbrook by the Grocers’ Livery Company. This was a City church without any parishioners when compared to Clapham Junction, and this provided Varah with the time to set up the service which would become the Samaritans.

Varah started with a single telephone on the 2nd of November 1953.

His connections in the publishing industry through his work on comics immediately led to some publicity for his new service, such as the following from the Daily Mirror on the 7th of December 1953:

“DIAL 9000 FOR WORDS OF COMFORT – A telephone emergency service, run on the same lines as the police 999 calls, will soon be available to people in distress who need spiritual aid.

All Londoners need do is dial Mansion House 9000, the number of the Telephone Good Samaritans, and advice will be given immediately.

The scheme has been thought up by the Rev. Chad Varah, 42, Vicar of St. Stephen’s in the City, and will be in operation within the next few months.

If a case is sufficiently urgent, a Good Samaritan will dash to the caller and try to comfort and help him or her, said Mr. Varah yesterday.

The Vicar hopes to enroll Samaritans – volunteer workers for his service – from all parts of London.

I want to spread the organisation so that there are at least two Samaritans for every four square miles of Greater London and the suburbs, he said.

I first got the idea from the many letters I received from people in mental and spiritual distress. And I have found that a chat, a kind word and some good advice from an outsider can often save a person’s life.

He said that he intended to deal with personal spiritual problems concerning everything from quarrels between married couples to would be suicides.

The qualifications Samaritans need are tact, patience and the ability to keep other people’s confidences, he said. Religion is a secondary requirement.”

The Daily Herald had a similar report, but ended with the following paragraph, which provides an indication of how many calls Chad Varah was receiving:

“Mr. Varah is now missing meals to keep up with the phone calls he is getting. The former vicar of St. Paul’s Clapham Junction, he has just taken over St. Stephen’s.”

He soon collected a group of volunteers together to take calls, and in February 1954 he handed over the responsibility to take calls to the volunteers leading to the organisation of the Samaritans.

Chad Varah was involved with the Samaritans for the rest of his life. He retired from St Stephen, Walbrook in 2003 after being rector of the church for 50 years. He died in 2007, just a few days before his 96th birthday.

A remarkable man, who started an organisation that must have saved countless lives since starting seventy years ago in St. Stephen Walbrook in 1953.

The City of London plaque to the founding of the Samaritans is next to a small alley, St. Stephens Row which runs alongside the church, and the rear of the Mansion House.

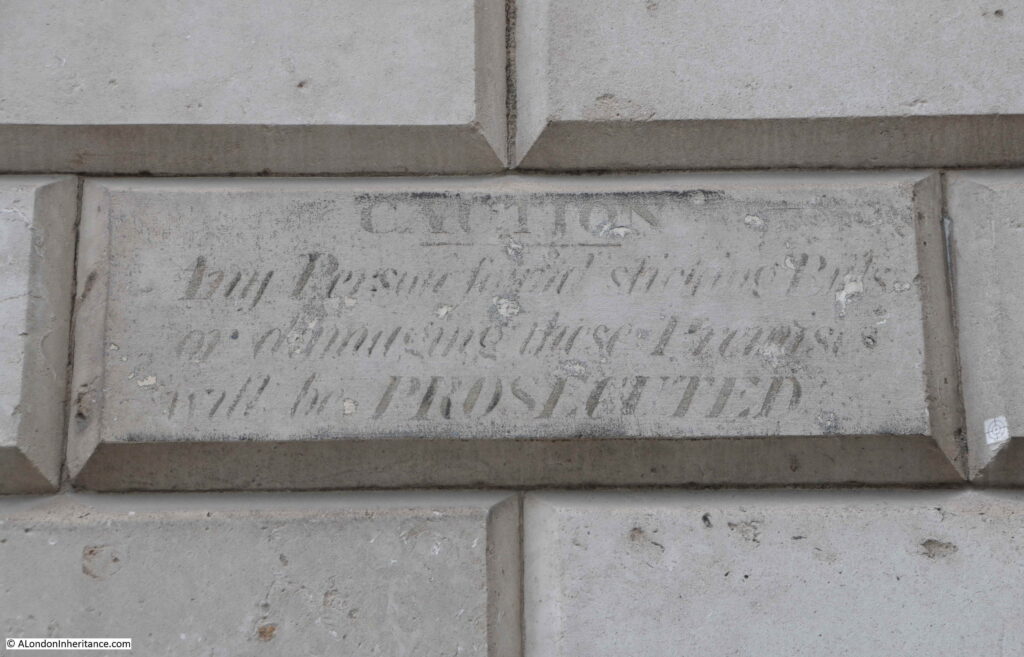

On the wall of the Mansion House close, to the plaque is a stone block, which I think warns that anyone sticking bills or damaging the walls will be prosecuted. There is no date, but from the faded script, and style, it is of some age:

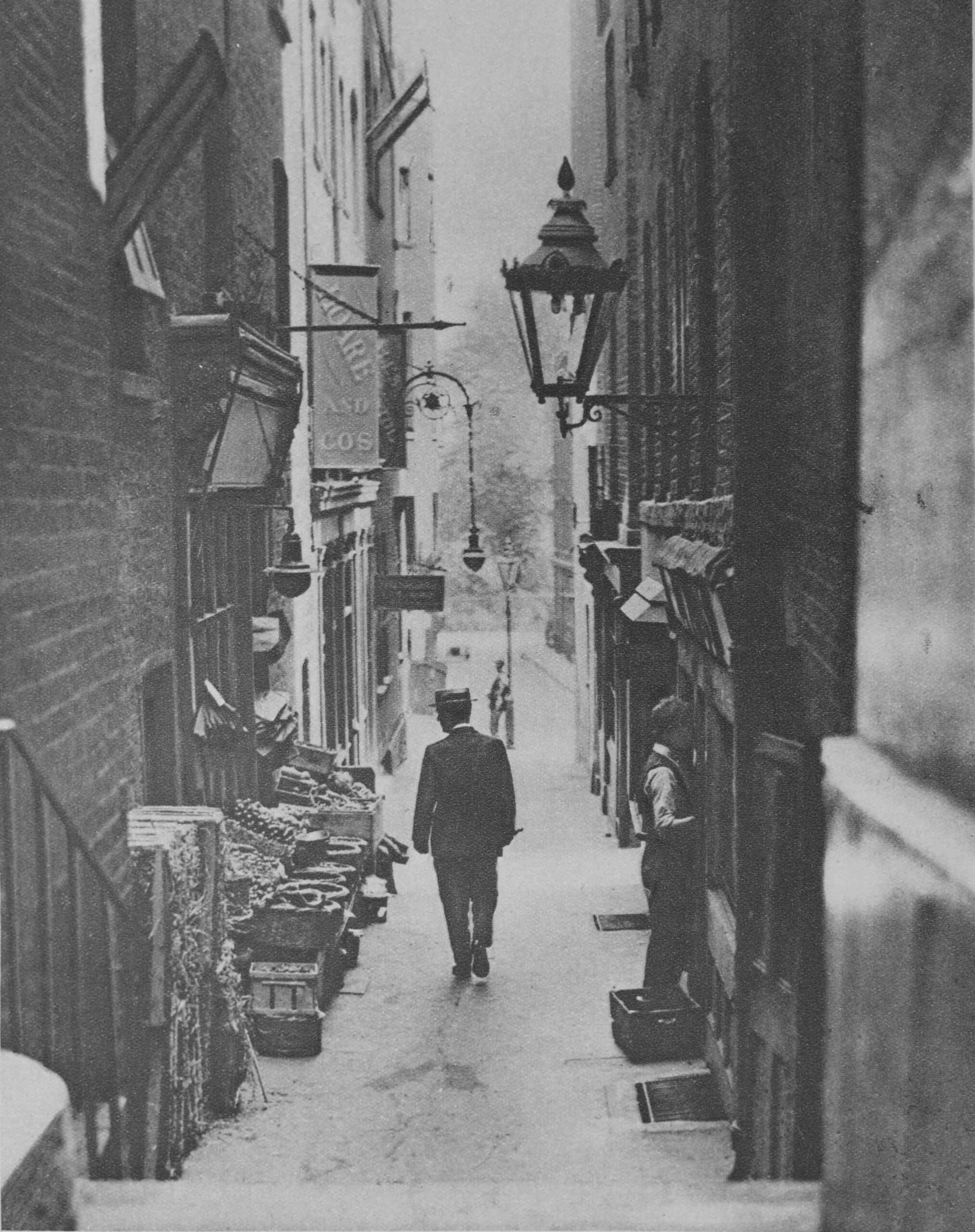

St. Stephen’s Row leads between the church and Mansion House:

I suspect St. Stephen’s Row dates from the construction of the Mansion House.

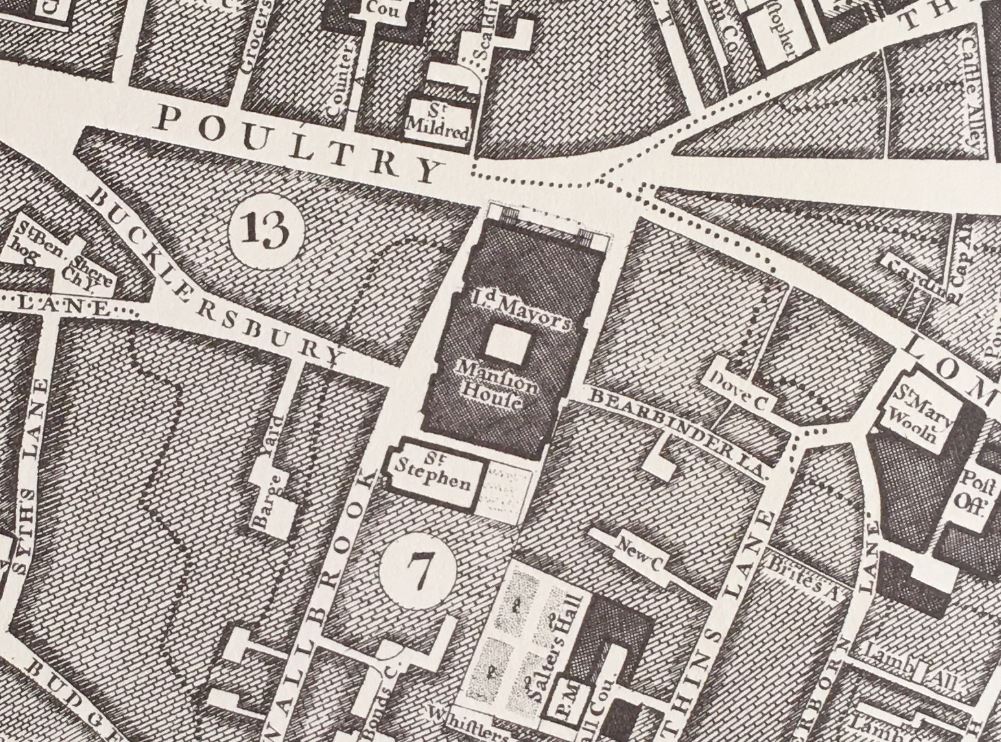

The first stone of Mansion House was laid in 1739 and the home of the Mayors of the City of London was completed in 1758.

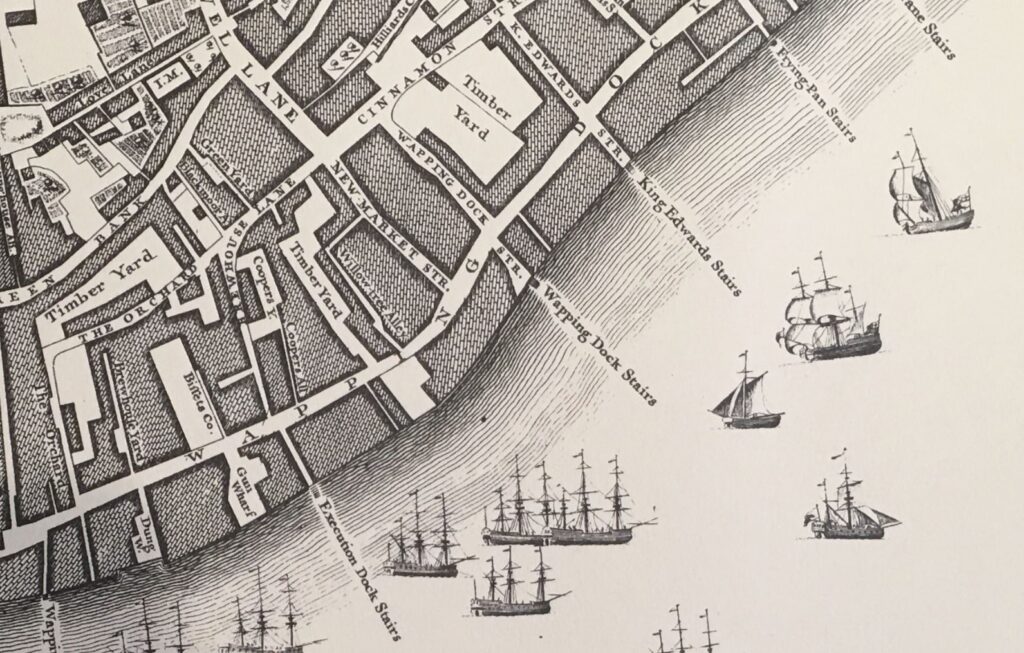

Although it was still under construction, by the time of Rocque’s 1746 map of London, it is shown on the map, and there is an alley between the Mansion House and St Stephen’s, which continues to the right of the Mansion House. Although it is not named on the map, it is the route of St. Stephen’s Row today:

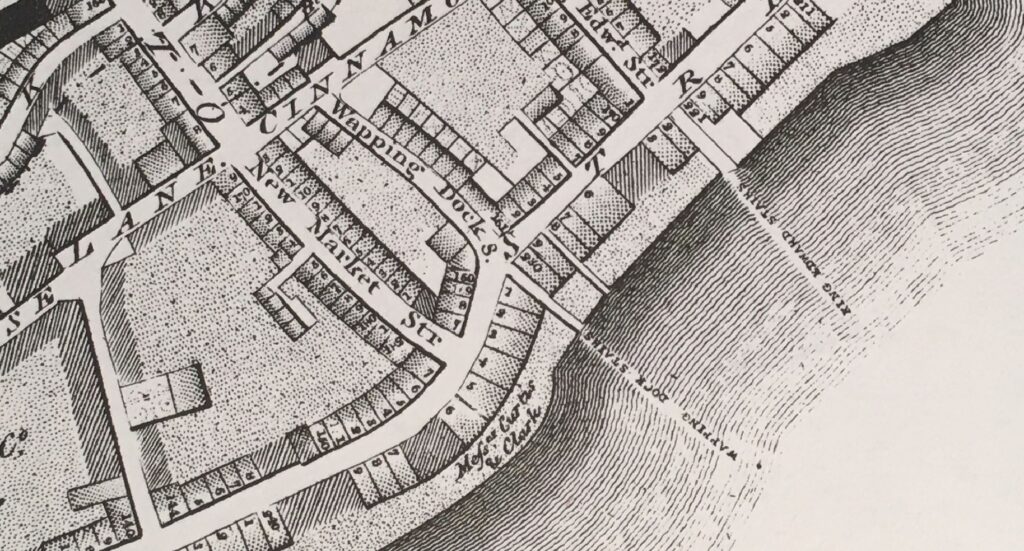

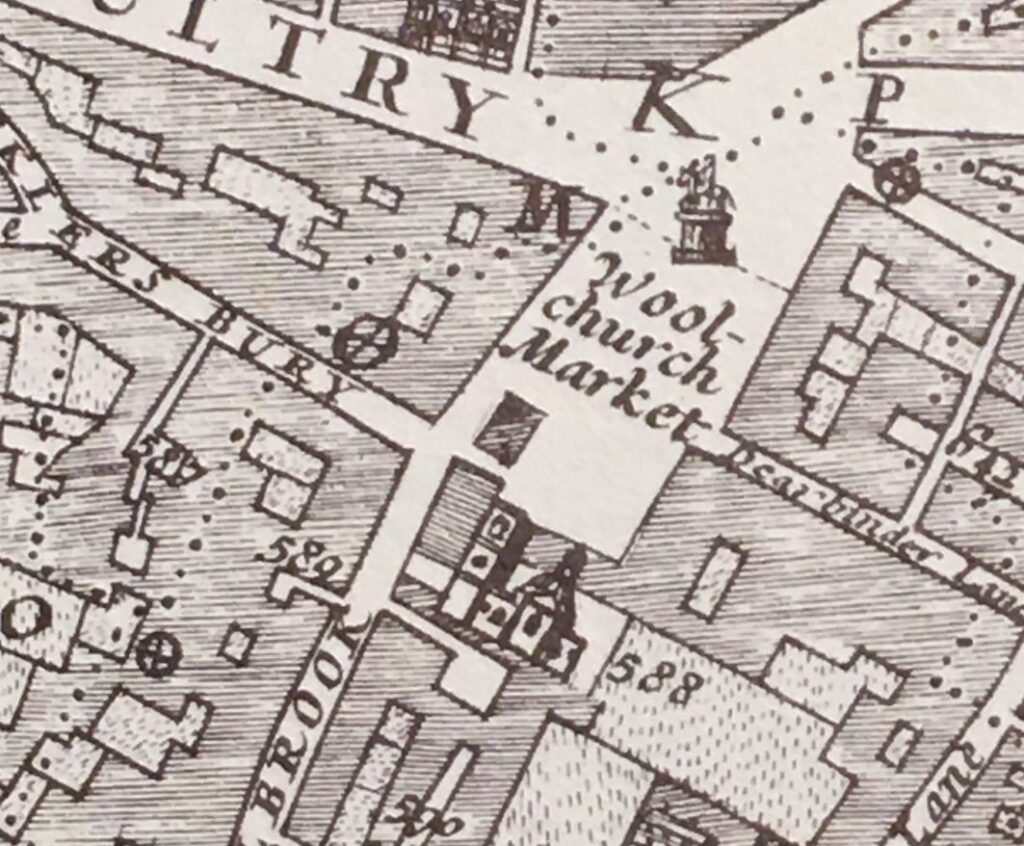

Going back to William Morgan’s 1682 map of London, and the space for the future Mansion House was then occupied by the Woolchurch Market. There looks to be buildings between the market and church, but there is no sign of the alley:

There was a church which stood where the Mansion House now stands called St Mary Woolchurch Haw. The church was lost during the Great Fire of 1666 and not rebuilt, and the market took the name of the church.

I have written about the church and the market towards the end of the post at this link.

The view along St. Stephen’s Row, with the church on the left and Mansion House on the right:

The entrance to the churchyard at the rear of St. Stephen Walbrook from St. Stephen’s Row:

Now to a very different location:

The Royal College of Physicians

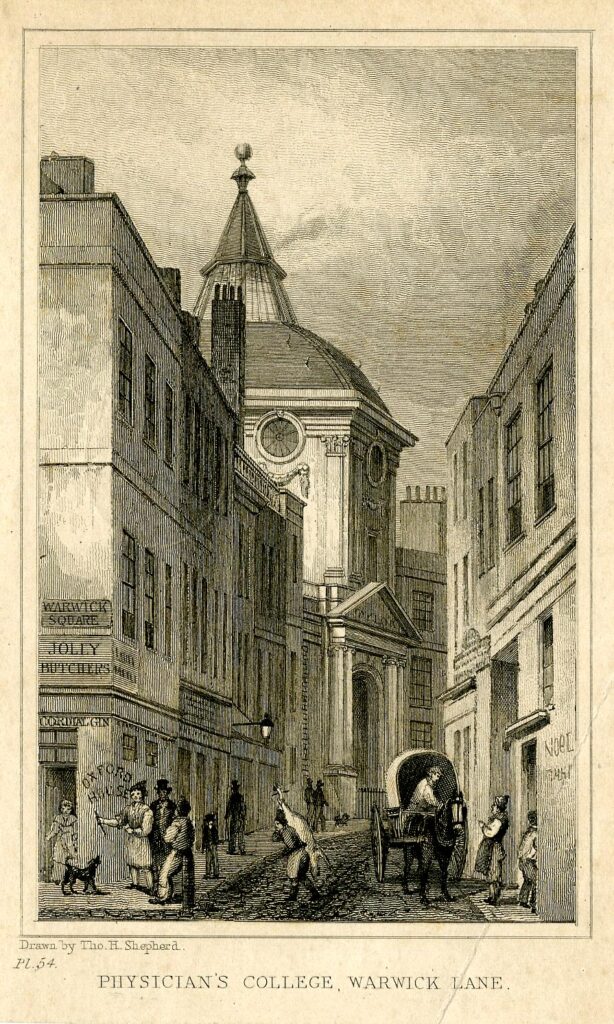

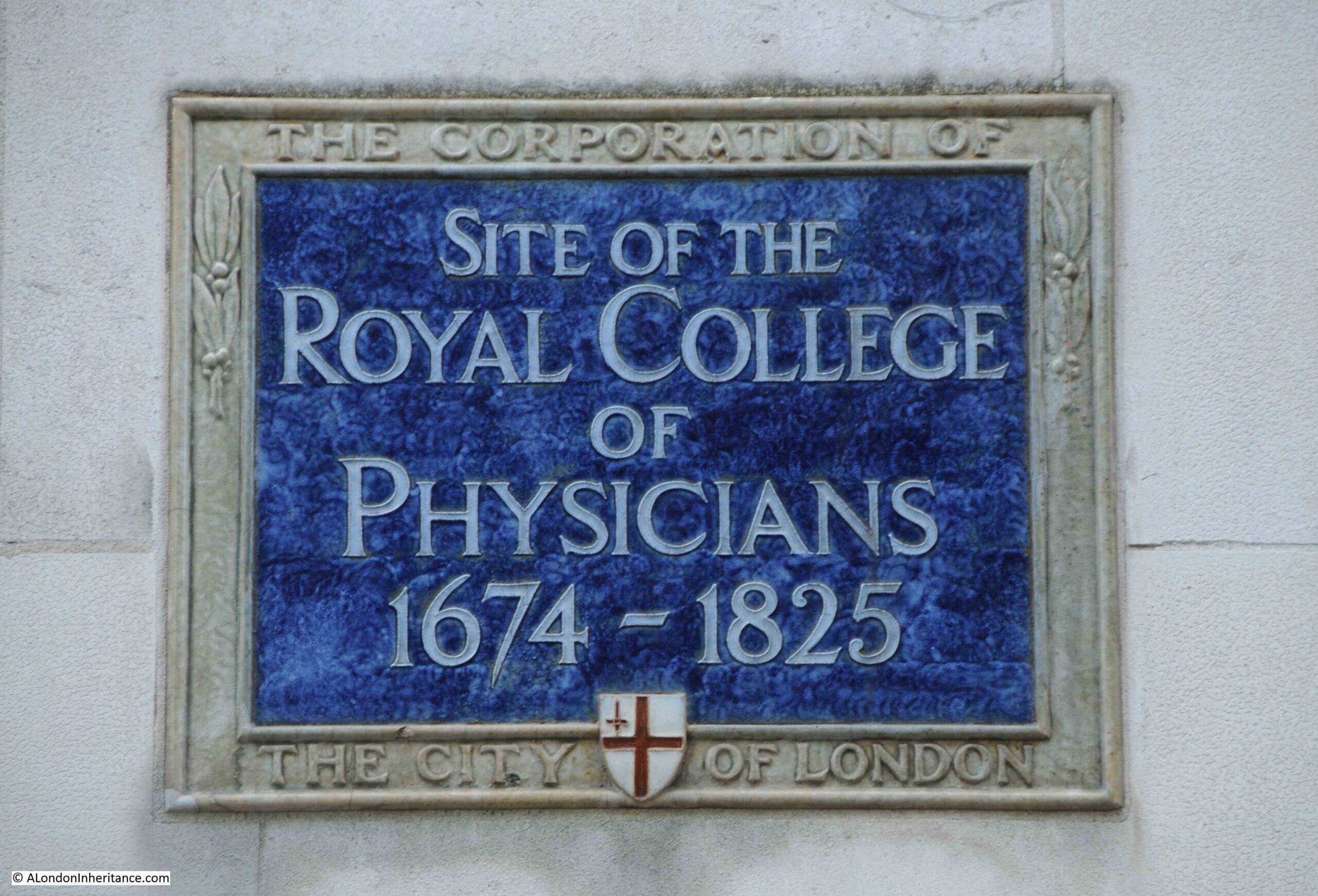

In Warwick Lane, which runs between Newgate Street and Ave Marie Lane, to the west of St. Paul’s Cathedral, there is a plaque shown arrowed in the following photo:

Recording that this was the site of the Royal College of Physicians between 1674 and 1825:

The origins of the Royal College of Physicians dates back to the early 16th century when a number of leading medical men, including Thomas Linacre, the physician to King Henry VIII became concerned about the state of medical practice in the country, the lack of any regulation, and the impact that untrained physicians were having on their patients.

Thomas Linacre, along with five other leading physicians, persuaded the kIng to allow the founding of a College of Physicians.

A Royal Charter was received and the College of Physicians was founded in London on the 23rd of September, 1518, and an Act of Parliament in 1523 extended the authority of the College from London to the whole of the country.

The “Royal” was added to the name after the restoration of the monarchy with Charles II in the later part of the 17th century.

The Royal College of Physicians original home in the City of London was destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire, and nine years later, following some successful fundraising, the Royal College purchased land and property in Warwick Lane.

The new building was designed by Robert Hooke, and had a large central courtyard with wings either side. There was a public gallery, an anatomy theatre which was topped by an octagonal dome, and a large library which was designed by Christopher Wren.

The view of the Royal College of Physicians in Warwick Lane © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The large courtyard at the rear of the block facing onto Warwick Lane © The Trustees of the British Museum):

By the early 19th century, the City was becoming a crowded, busy and dirty place, and the building in Warwick Lane had deteriorated so was sold in 1825, and finally demolished in 1890.

Following the exit from Warwick Lane in 1825, the College moved to Pall Mall, before moving in 1964 to Regents Park, where they remain to this day.

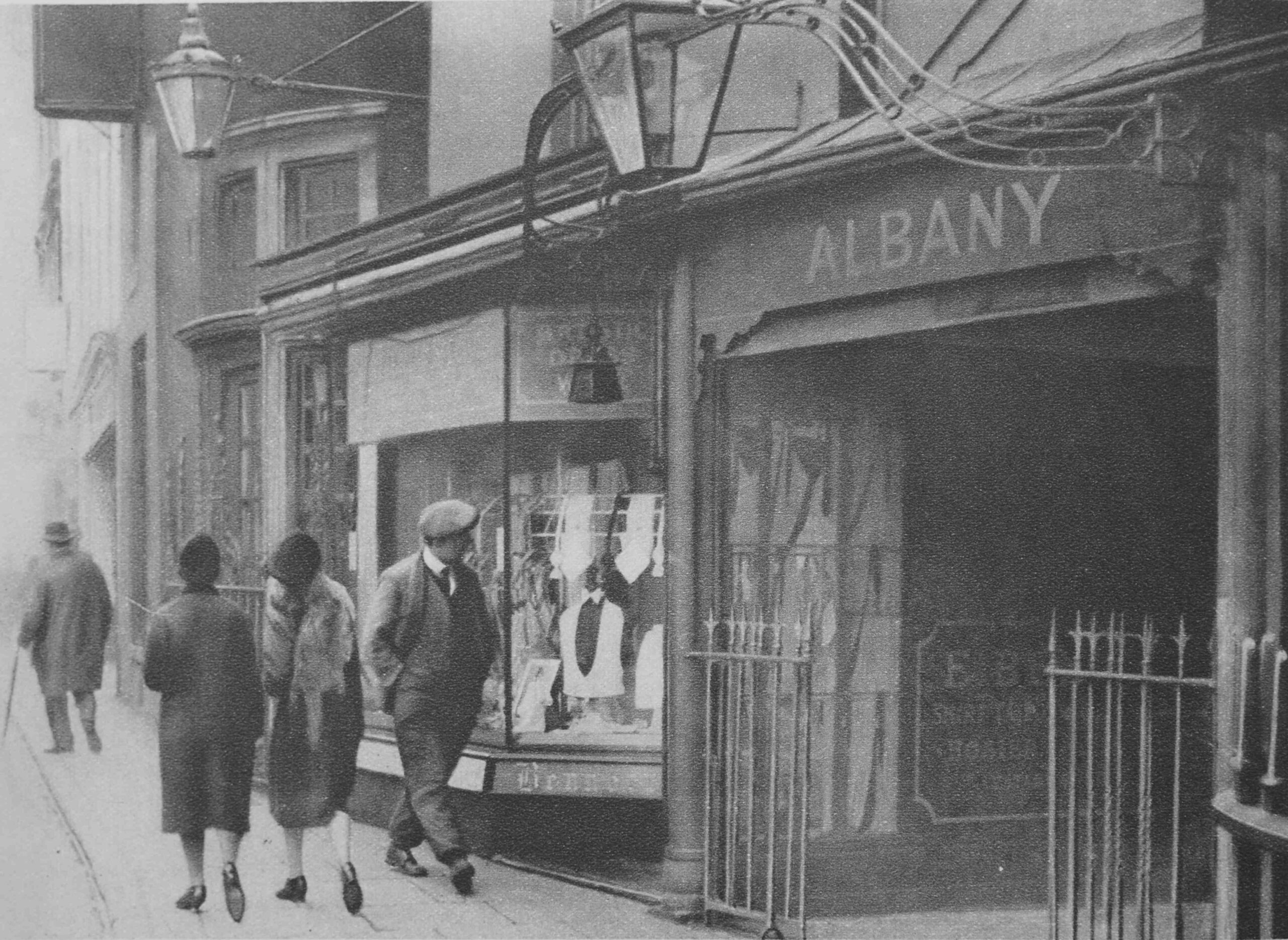

Although not marked by a plaque as it is still in use, there is an interesting building next to the plaque:

Cutlers Hall

This is Cutlers Hall:

My go to book on the City’s Companies (The Armorial Bearings of the Guilds of London by John Bromley, 1960) records the following about the Cutlers:

“The cutlery trade of the Middle Ages included the making of swords, daggers and knives of all kinds. originally it was a highly specialised industry, comprising the separate trades of hafters who made handles or hafrts, bladesmiths and sheathers, with the cutlers acting as assemblers and salesmen. Both hafters and sheathers were ultimately merged into the Cutlers Company while the bladesmiths were first united with the Company of Armourers, and then allowed by a decision of the Court of Aldermen of 1528 to depart unto the fellowship of Cutlers at will.”

Given their trade, you would expect the Cutlers to be one of the old Company’s of the City, and they are indeed, with the first mention of an organised craft of Cutlers in 1328 when seven cutlers were elected to govern the craft and search for false work.

The Cutlers moved to the hall we see today in Warwick Lane in the 1880s, when their original hall in Cloak Lane was demolished to make way for the construction of the Inner Circle Line by the Metropolitan and District Railway Company (now the route of the Circle and District lines between Mansion House and Cannon Street stations).

I wrote a post about the original hall, and the construction of the railway in this post: Cloak Lane, St John the Baptist, the Walbrook and the Circle Line

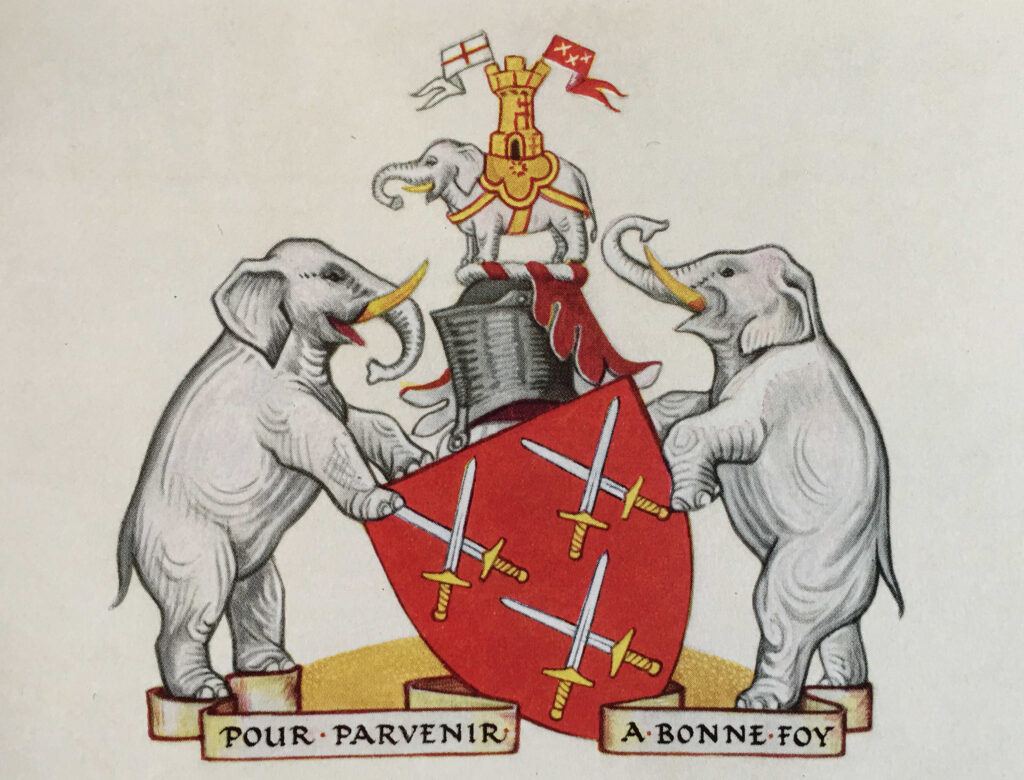

The arms of the Cutlers can be seen above the entrance to the hall, and the following image shows the arms:

The swords are an obvious reference to one of the products of the Cutlers. The use of elephants in the arms is old, and was recorded in 1445 where members of the Cutlers wore elephants as decorations on their coats or shields when the City welcomed Queen Margaret on her marriage to Henry VI in 1445.

The use of the elephant may be down to the use of ivory in the hafts (handle of a knife) made by members of the Company.

The elephant is featured in the sign hanging from the side of Cutlers Hall:

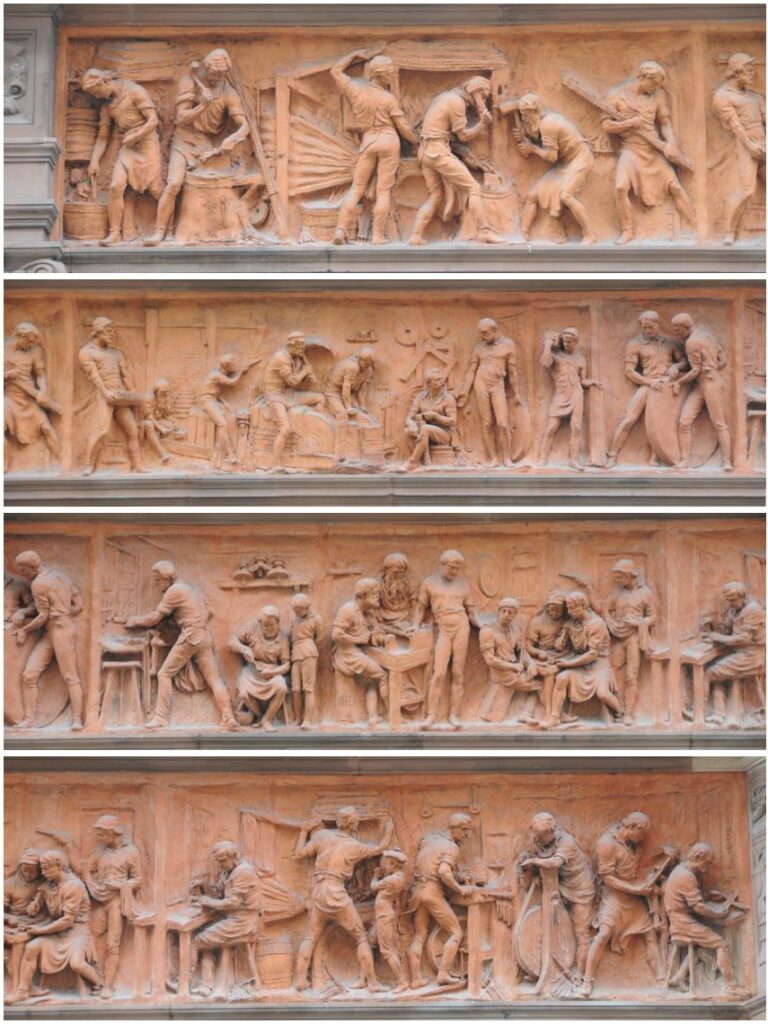

One remarkable feature of Cutlers Hall is the frieze along the façade of the building. The frieze is a detailed view of the work of cutlers, and was created by the sculptor Benjamin Creswick.

The following image shows the frieze, with the left most panel at the top:

The red terracotta frieze is a wonderful record of the work of the trades that formed the Cutlers Company.

Now to St. Paul’s Churchyard to find two very different organisations, starting with the:

Young Men’s Christian Association

In front of the cathedral, there is an office block with shops on ground level running along the line of St. Paul’s Churchyard. There is a covered walkway in front of the shops, and at the western end of this walkway, next to the old gate of Temple Bar are two plaques, the first arrowed in the following photo:

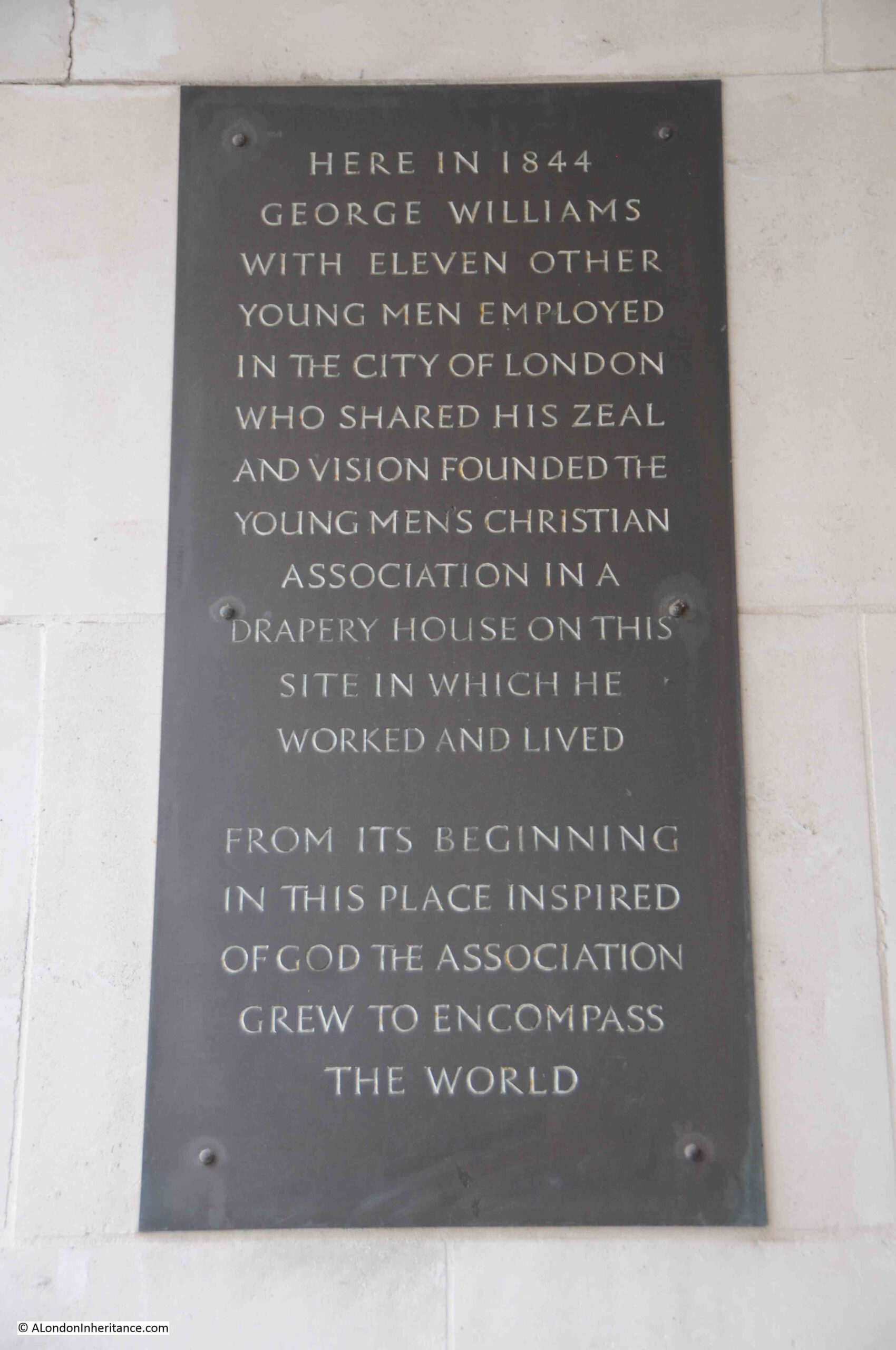

The arrow is pointing to a plaque on the wall recording the founding of the Young Men’s Christian Association:

The plaque states that in 1844, George Williams with eleven other young men employed in the City of London…….Founded the Young Men’s Christian Association. But why here?

The Drapery House mentioned in the plaque was the offices, factory and warehouses of Hitchcock, Williams & Co.

The firm was established in 1835 by George Hitchcock and a Mr. Rogers, who would leave in 1843. George Williams (mentioned in the above plaque) who originally joined the company as an apprentice, became a Director with Hitchcock in 1853 when the partnership Hitchcock, Williams & Co was formed. Always based in St. Paul’s Churchyard, firstly at number 1, then at number 72, with the firm expanding to take in many of the surrounding buildings.

George Williams, as well as becoming a partner with Hitchcock, received a knighthood from Queen Victoria for services, which included the inauguration of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) which was founded in a room of the company’s premises in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

The history of the YMCA states that the group founded the YMCA as “a refuge of Bible study and prayer for young men seeking escape from the hazards of life on the streets of London”.

The buildings of Hitchcock, Williams & Co. were destroyed during the raids of the 29th December 1940. A paragraph in the newspaper reports of the raid included a mention of the company and the YMCA:

“The historic room in which the Young Men’s Christian Association was started was among the places destroyed on Sunday night. With seven other buildings, the George Williams Room – named after the founder, the late Sir George Williams – was burned to ashes. It was situated in the premises of Messrs. Hitchcock, Williams and Co, manufacturers, warehousemen and shippers, of St. Paul’s Churchyard, and was originally one of the bedrooms used by the 140 assistants employed in the Hitchcock drapery business.”

As stated in the plaque, “from its beginning in this place inspired of God the association grew to encompass the world” and all because George Williams started as an apprentice here, in one of the many businesses that once lined St. Paul’s Churchyard.

I wrote a post dedicated to the company’s experience in the 1940s in this post: Operation Textiles – A City Warehouse In Wartime.

The Grand Lodge of English Freemasons

There is another plaque in the same place as the plaque recording the YMCA. Directly opposite, in the entrance to the covered walkway shown in the photo of the location of the YMCA plaque is the following:

The significance of the plaque and the site is the reference to the Grand Lodge, as prior to 1717 there had been four London lodges, and on the 24th of June 1717, they met at the Goose and Gridiron Tavern in St Paul’s Churchyard, and elected Anthony Sayer as the first Grand Master.

This was the first Grand Lodge not only in the country, but also across the world of Freemasons.

The four original lodges had all met in pubs; the Goose and Gridiron in St. Paul’s Churchyard, the Crown in Parkers Lane, the Apple Tree in Covent Garden, and the Rummer and Grapes (no location given).

Pubs continued to be used for meetings, but in 1767, the Grand Master, the Duke of Beaufort had the idea for a Central Hall, and a committee was formed to purchase land for a new hall, and a “plot of ground and premises consisting of two large, commodious dwelling houses, and a large garden situated in Great Queen Street” were purchased.

The hall built on the site was opened in 1776, and the Freemasons still occupy the same site, with the current hall being built between 1927 and 1933.

The plaques featured in today’s post show the wide range of organisations that have made the City of London their home over the centuries, or have been founded in the City.

From organisations such as the Samaritans, who must have been responsible for saving and helping so many people since 1953, to global organisations such as the YMCA, City Livery Companies, Medical Institutions and the Freemasons.

And they all continue to make their mark today.