A couple of months ago, I wrote about St John’s Gate in Clerkenwell which was once part of the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. The priory occupied a large amount of land in Clerkenwell, and today I am exploring another part of the history of the area with a visit to the Priory Church of the Order of St John.

The Priory Church of the Order of St John visible when standing outside today is a post war building, but down in the crypt there is still evidence to be found of the original Norman and Medieval building, part of the church’s long and fascinating history, and some of the oldest in London.

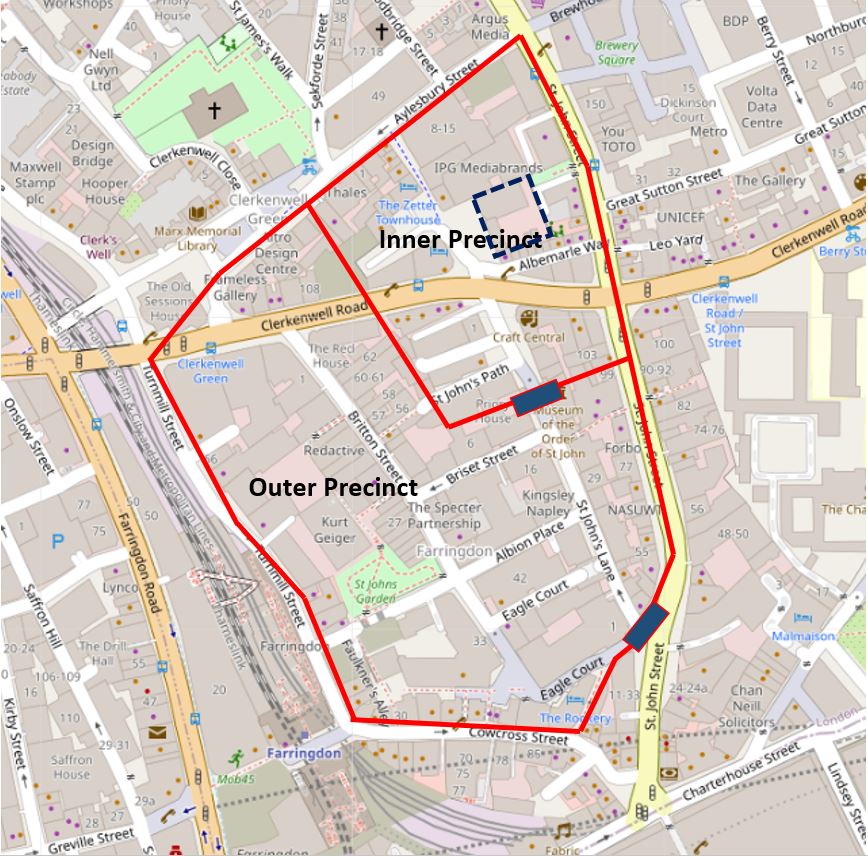

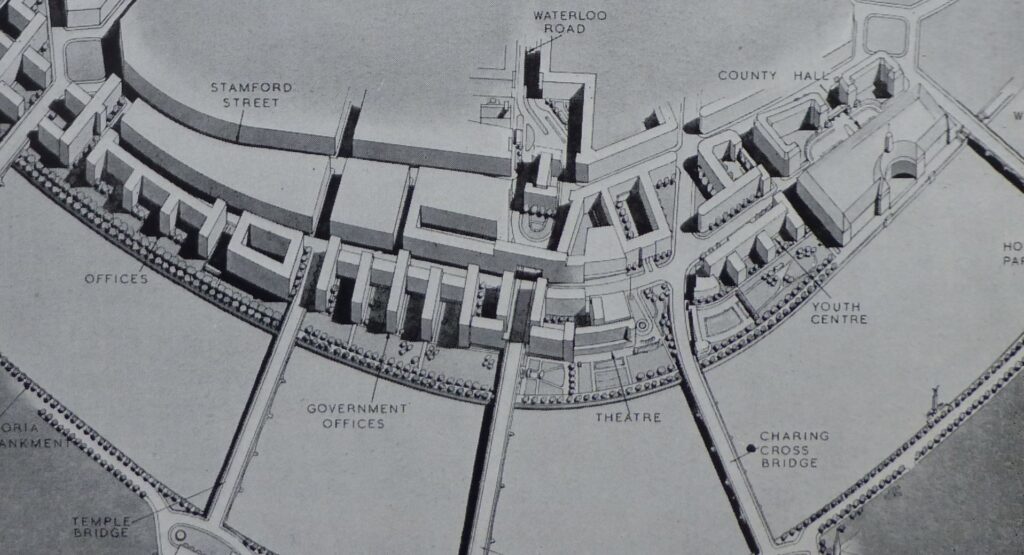

The following map is from my earlier post on St John’s Gate showing the outline of the inner and outer precincts of the original priory. The solid blue rectangle is the location of the gate and I have added the location of the church, in the heart of the old inner precinct, by a blue, dashed rectangle.

If you walk up from the location of St John’s Gate, cross Clerkenwell Road and stand in St John’s Square, you will find the Priory Church of the Order of St John, a rather fine brick building. The main body of the church is to the left, and the entrance to the Cloister Garden is through the large central entrance.

The current church is built on the site of the original 12th century priory church. The design of the 12th century church was based on the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, in that it had a large round nave, leading back to a narrow raised chancel built over a crypt.

This design was used by both Hospitaller (the order which occupied the Clerkenwell priory) and Templar churches. We can get an idea of what the circular nave may have looked like by comparing with the London Temple church:

Parts of the original circular nave were discovered in 1900, and today the outline of the nave is marked by granite setts which we can see in the photo below, in front of the church:

Parts of the original circular nave were discovered in 1900, and today the outline of the nave is marked by granite setts which we can see in the photo below, in front of the church:

As the Priory grew in wealth and influence, so did the church, and the church was quickly expanded, including rebuilding the circular nave as a more traditional rectangular nave.

Prior Thomas Docwra carried out some major restoration work on the church at the end of the 15th century, and the English antiquarian William Camden would describe the church as “increased to the size of a palace, and had a beautiful tower carried up to such a great height as to be a singular ornament of the City”.

A similar description of the church was recorded by Stowe who wrote: ‘a most curious peece of workemanshippe, graven, gilt, and inameled to the great beautifying of the Cittie, and passing all other that I have seene’

Docwra’s work on the church included the addition of his own private chapel on the south wall of the church.

It must have been an impressive sight, however the church would soon suffer the same fate of many other buildings connected with religious orders, when King Henry VIII seized the properties and dissolved the original Order of St John, including the Priory Church.

Various parts of the fabric of the church were taken to be used for buildings within the Royal Palace at Westminster, and in 1549 the nave and tower of the church were blown up by Lord Protector Somerset so the materials could be used for the construction of his house in the Strand (Lord Protector Somerset. or Edward Seymour, took the title of Lord Protector between 1547 and 1549 following the death of Henry VIII and whilst Henry’s son, King Edward VI, was still a child. As was typical with many ambitious members of the Tudor court, he would have a rapid fall from grace and was executed at Tower Hill in January 1552).

The remains of the church were then used for various purposes, storage, further demolition, and some locals used Docwra’s chapel as a place of worship, parts of the church were converted to a private house, and the chancel being rebuilt as a private chapel.

It was not until the early 18th century that the building became a formal church again. It was used as a meeting house by the Presbyterian preacher William Richardson, who would go on to be ordained as a Church of England minister. He then reopened the church as a Church of England building, which was a timely decision as during the early part of the 18th century, London’s rapid expansion created the need for additional churches to service a rapidly growing population.

Richardson proposed to the commission that had been set up to build fifty new churches across London, that they should acquire the church as a second parish church for Clerkenwell as the only other church (St James, just north of Clerkenwell Green) could not support the number of people then living in Clerkenwell.

Richardson’s proposal did not succeed and lawyer Simon Michell then purchased the church, and had better luck with the Commission as they agreed to purchase the church for the sum of £3,000. The building was consecrated as St John’s, Clerkenwell’s second parish church on the 27th December 1723.

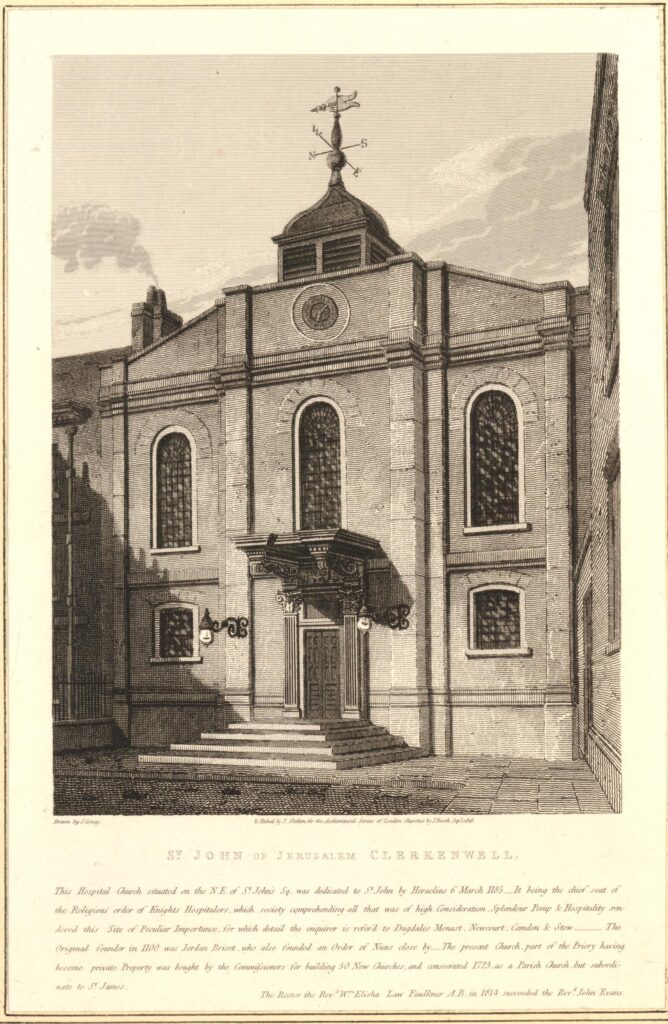

Following building works between 1721 and 1723 carried out by Simon Michell, and further work between 1812 and 1813 by James Carr, the church took on the appearance of a more traditional London church, although with a small rectangular tower, rather than the larger tower and spire seen on many other London churches. The following print shows St John’s, Clerkenwell, in 1818 (©Trustees of the British Museum).

St John’s would continue as the second parish church of Clerkenwell until 1931. The population of Clerkenwell had been in decline during the first decades of the 20th century. Industry was transforming from small workshops, to larger establishments requiring larger buildings which were replacing many of the 18th and early 19th century housing.

The modern Order of St John was formed during the later years of the 19th century in the original gatehouse of the Priory between the inner and outer precinct, known as St John’s Gate.

The modern Order provided a perfect solution for the future of the church, as the Order had been using the church for their religious services since the 1870s, and the Order had contributed to the maintenance and restoration work that took place towards the end of the 19th century.

In 1931 the parish of St John was returned to St James, and the church of St John was formerly handed over to the modern Order, thereby reuniting the gatehouse and church for the first time in almost 400 years within a modern Order of St John.

Use of the church by the Order in the form of the original parish church building would not last for long. During bombing raids on London in May 1941, the church was hit by incendiary bombs and the resulting fires destroyed the interior of the building along with the roof leaving only the outer shell of the building standing.

The following photo from 1946 shows a service taking place in the roofless church, the Order’s annual service on St John’s day with the Archbishop of Canterbury who had recently been enthroned as the Prelate of the Order of St John of Jerusalem.

Soon after the destruction of the church, the Order of St John had started planning for a rebuild, and as the original outer walls were intact the intention was to rebuild around the walls rather than a complete new church.

The first new design came from the Gothic architect J. Ninian Comper.

In his 80s, Comper was known for his extravagant and expensive designs, and his proposal for the new priory church was based on a recreation of an original Hospitaller church, with a large, ornate octagonal nave. The cost of the design was estimated at £200,000 – a considerable sum of money to be raised when so much else needed to be rebuilt in the city.

Comper’s age was also a concern and he tended to work on his own. When asked who in his office would take over his design if he died, his response was apparently “Did Michelangelo have an office?”.

Comper would go on to design the magnificent new window in St Stephen’s Porch at the south end of Westminster Hall. A magnificent 50 foot high, 28 foot wide ornate, stained glass window. The window is the main memorial to members and staff of both Houses of Parliament and replaces an earlier Pugin window that was destroyed by bombing in December 1940.

The architects Paul Paget and John Seely were called in to provide an alternative and much cheaper design for a rebuilt church. They had already been responsible for restoration of some historically significant houses in nearby Cloth Fair where they lived and had their office, and they both had the role of surveyor to St Paul’s Cathedral.

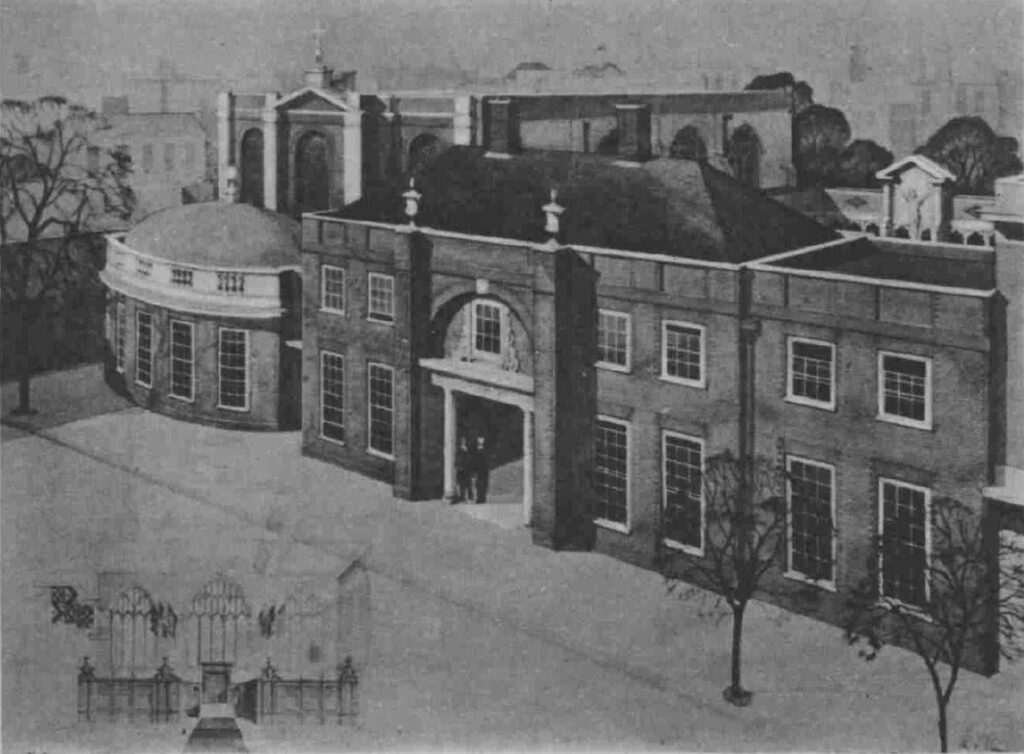

Their design was for a much more restrained building. Brick facing St John’s Square and a relatively plain rebuild of the church using the original outer walls.

The following drawing from 1955 shows their proposed design.

The church today looks almost identical to their original design, however if you look at the main body of the church on the left and the domed front of the church we can see that some decoration did not get built – probably to save money.

The interior of the church is relatively plain, with the white painted original walls and a black and white checkerboard floor.

On the left of the church as we face the altar are the banners of the other priories of the Order of St John, in countries such as Canada, the USA and South Africa:

Whilst on the right are the banners of the current Knights and Dames of the Order:

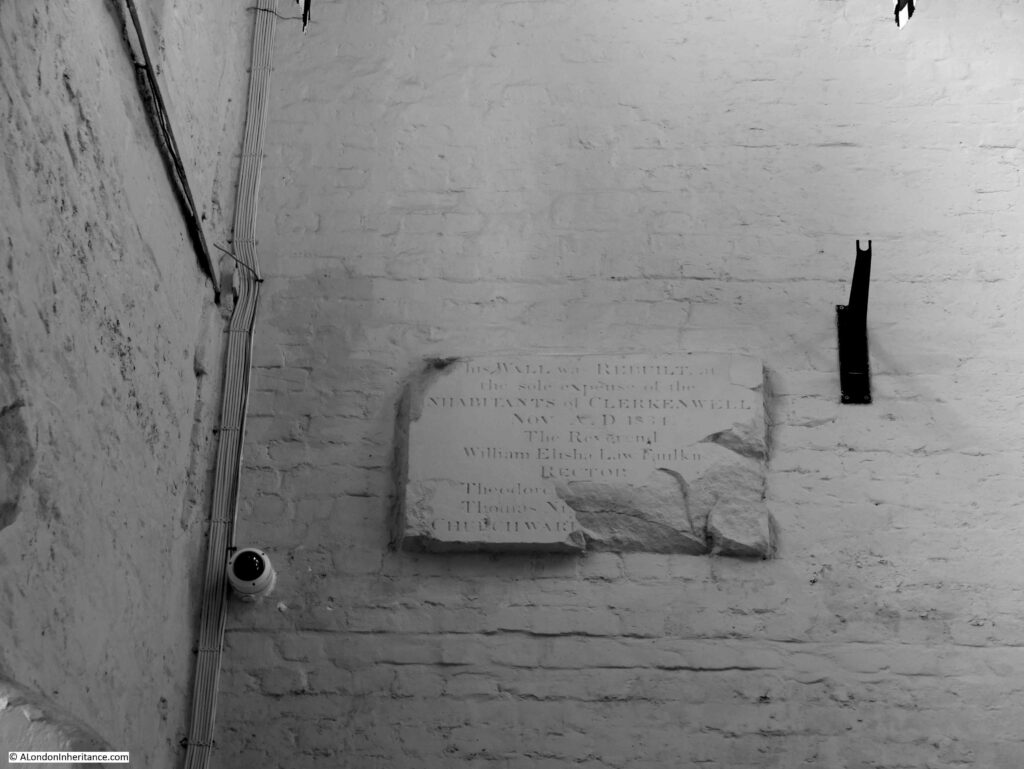

On one of the walls is a reminder of when the building was a parish church for Clerkenwell:

The plaque reads: “This wall was rebuilt at the sole expense of the inhabitants of Clerkenwell, Nov AD 1834. the Reverend William Elisha Law Faulkner, Rector”. The surnames of the churchwardens at the bottom right have been lost.

In a corner of the church is some of the original equipment used by the St John Ambulance which the new Order of St John set-up in 1877.

If we want to see parts of the original 12th century Norman church of the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem we need to descend to the crypt. The fact that the church was hit by incendiary bombs rather than high explosive meant that the crypt survived the war with minimal damage, and as we enter the crypt, we have the following view:

The stained glass at the end of the crypt gives the impression that this is above ground and that sunlight is behind the windows. In reality, artificial lighting is behind the stained glass.

As we look towards the altar, the first three arched sections are mid 12th century and the two furthest are slightly later dating from around 1170.

The white painted crypt today is a bright space, but during the crypt’s years as part of the parish church this would have been a very different place, with the crypt piled high with coffins.

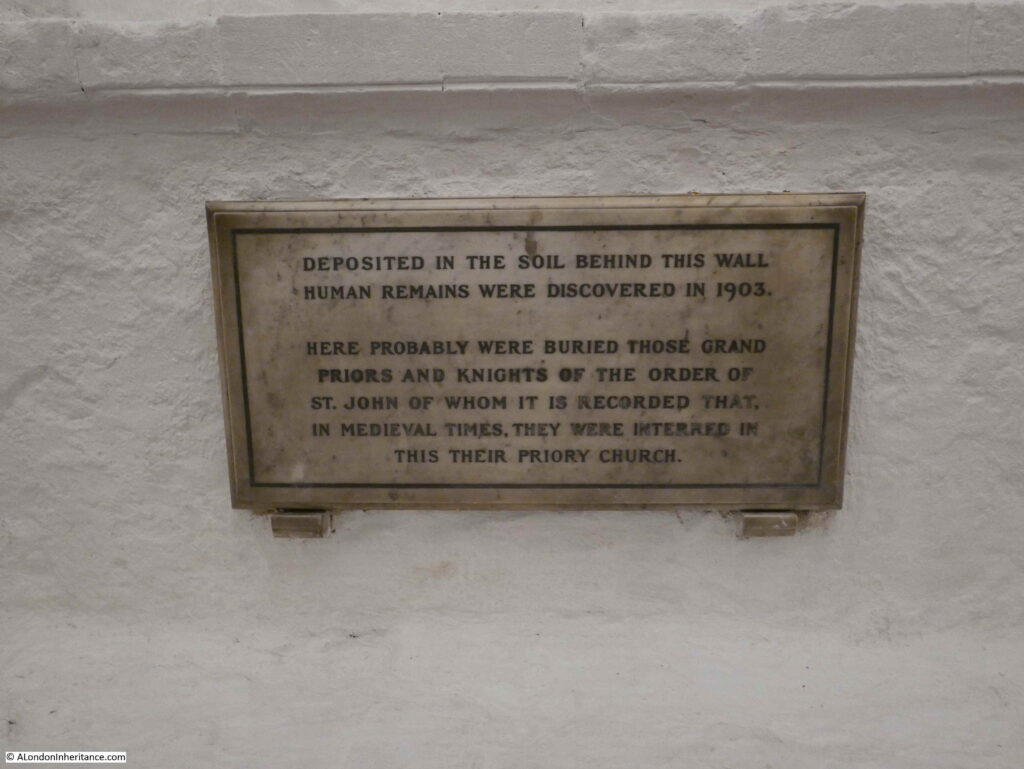

The crypt was finally cleared in 1894 following the burials act of 1853 which outlawed the use of London’s crypts and churchyards for burials. Many coffins were removed to Brookwood Cemetery, however some were bricked up in the side vaults that line the central part of the crypt and older remains were discovered in 1903:

Just to the left of the crypt entrance is part of one of the original mid 12th century arches:

Although the crypt is today painted white, it originally may have been more colourful. P.H. Ditchfield writing about the church and crypt in 1914 in his book London Survivals states that “Traces of colour can still be seen on the arches and ribs”.

The Islington Antiquary Society visited the crypt in 1910 and were told two interesting stories about the crypt:

- That when the crypt was used for burials, a sexton was working with body snatchers and on investigation, many of the coffins were found to be empty

- That Fanny Parsons, also known as scratching Fanny, the young girl who convinced visitors that the sounds she created were caused by the Cock Lane ghost, had been buried in the crypt. An attempt had been made to find Fanny’s coffin, but it was believed that the name plate had been removed

The view along the crypt towards the entrance.

Along the side of the crypt are low stone benches running the length of the wall, implying that these may have been used for communal seating and during the Archbishop of Canterbury’s visit in 1946, Knights of the Order were seated along these benches.

To the side of the crypt is a rather impressive effigy of a knight. Donated by a member of the Order in 1915, the effigy is believed to have come from Spain, and does portray a member of the original Order, with the Maltese Cross emblazoned across the knight’s chest.

The identity of the knight is not known for certain, however it is one of the most impressive alabaster figures in the country.

Towards the end of the crypt, there are two rooms on either side of the central crypt. The room on the left as you face the altar may have been used as a Treasury by the original Order. the room on the right is today the South Chapel:

Turn left as you face the altar and there is a morbid reminder of death:

This is all that is left of the canopied marble monument to Prior Weston, the last prior of the original order at the time of the reformation.

The windows above show the four saints of the British Isles, with figures and shields representing former priors, including Prior Robert Hales. Again, the window is backlit by artificial light to give the impression of natural light.

The monument was erected in St James Church, in nearby Clerkenwell Close, but was pulled apart when the church was demolished for a rebuild. The effigy remained in the crypt of the new church, but was moved here in 1931.

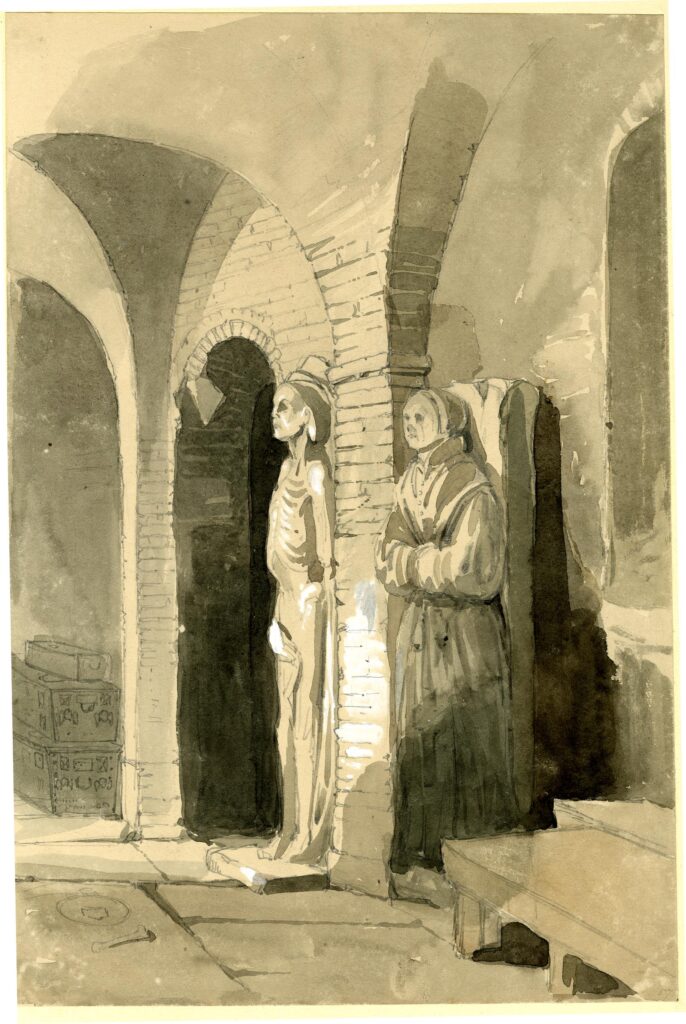

The effigy is a momento mori, where the figure is portrayed almost as a hollow eyed, emaciated corpse. The intent was to remind people of the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures, and to focus their minds on the afterlife.

The following print from 1842 shows the effigy of Prior Weston in the vaults of St James Clerkenwell along with an effigy that may have been Lady Elizabeth Berkeley (©Trustees of the British Museum).

There is one more feature of the Priory Church of the Order of St John to explore. This is back outside and through the entrance and gates in the building to the right of the church, where we find the Cloister Garden.

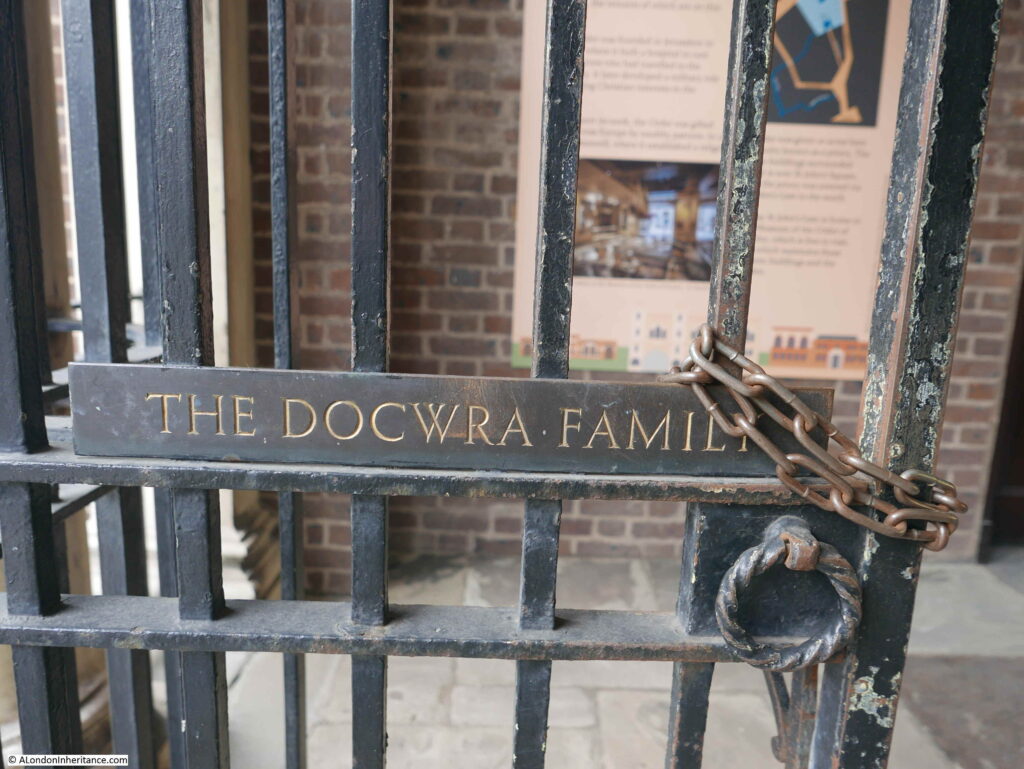

The entrance to the garden is formed by the Docwra Memorial Gates.

Thomas Docwra was one of the 16th century Priors of the Order, when the fortunes of the priory were at their highest and substantial building work was being done around the Priory.

As an example of the centuries of continuity that you can often find in the city of London, the same Docwra family donated the money for the gates as part of the post-war creation of the gardens.

Following the post war restoration of the church, the garden was relatively plain, consisting of grass and a central fountain. A recent grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Wellcome Trust has supported a redesign of the garden and new planting.

Planting takes us back to the original Medieval Hospital of the Order of St John, as the planting consists of a range of herbs which would have been used in the treatment of patients for a range of complaints.

- Rose petals – antiseptic qualities

- Peppermint – helps relieve stomach aches

- Lavender – used to treat burns, scratches and other minor skin ailments

- Chamomile – used to reduce swelling and helps to heal wounds

From the garden. we can see the south wall of the church and the mix of architectural features, brick and stonework that come from the centuries of different use of the building, many of which have left their mark in the walls.

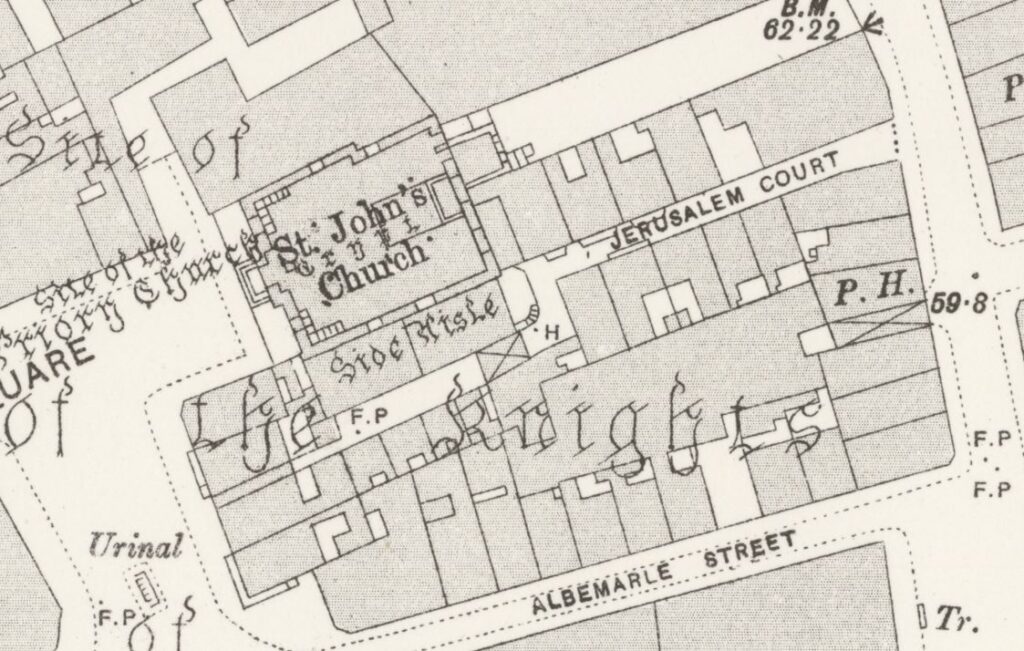

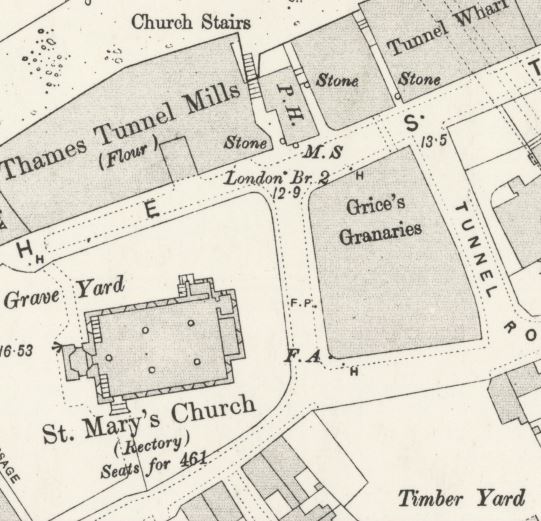

Prior Docwra had his own memorial chapel in Jerusalem Court which originally ran along the garden, with the chapel up against the church. In the following extract from the 1894 OS map, up against the south wall of the church are two buildings labelled Side Aisle. These were later buildings, one of which was reported to still contain evidence of Docwra’s chapel (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

Jerusalem Court is shown running from St John’s Street on the right, then through a ground floor gap in the buildings (the box with an X), and alongside the buildings up against the church wall.

This section of Jerusalem Court is now part of the Cloister Garden, directly in front of the camera in the photo below.

The intention with the post-war development of the Cloister Garden, was to have a four sided cloister which would form a memorial for those of the St John Ambulance Association and Brigade who had lost their lives during the two world wars, but again money was short so the planned cloister and memorial was only built along the eastern end of the garden.

The gardens form a tranquil and peaceful place, in what in more normal times is a very busy part of Clerkenwell, and whether it is the herbs we are surrounded by, or the medieval stone work of the southern wall of the church, the garden brings to the 21st century both the origins and the current work of the Order of St John.

The Priory Church of the Order of St John is a fascinating place. A tangible link with the original medieval Order, the present day Order and the crypt where part of one of the oldest buildings in London can be found.

Tours of the church will be available through the Museum of the Order of St John at St John’s Gate, and the Cloister Gardens are often open.