On a cold, windy and grey day in February, a day that seems very different to the weather we are having in June, I walked to the sites in Bethnal Green, Mile End Road and Stepney, continuing in my project to visit all the sites listed as at risk in the 1973 Architects’ Journal issue: New Deal for East London.

I had intended to cover all these locations in a single blog post, however I keep finding things of interest during these walks, and I did not have the time to write the full post, and did not want to impose such a lengthy post on readers, so I split into two.

A few weeks ago was the post on Mike End and Stepney, and today I am in Bethnal Green.

The post covers sites 49 to 52, where I also find an 18th century boxer and an interesting walk down to Mile End Road.

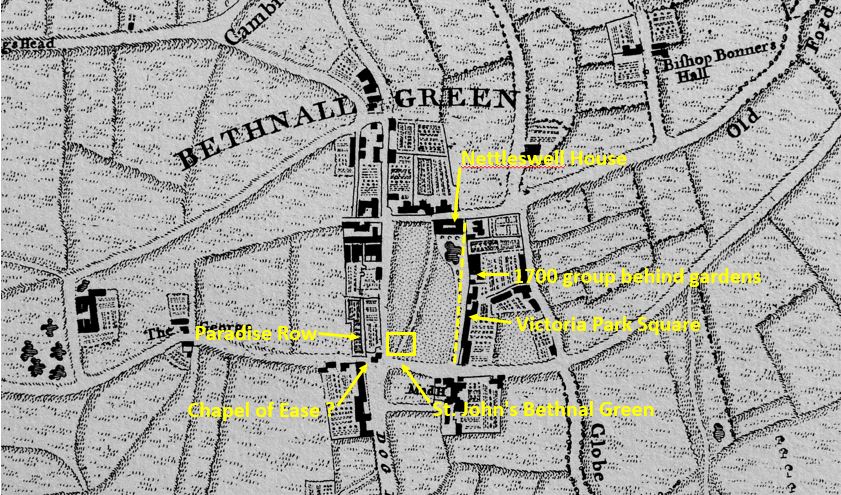

The area I will be walking is very built up, and has been since the early decades of the 19th century, however in 1746, Bethnal Green was still a hamlet surrounded by fields. Despite the very rural nature of Bethnal Green in 1746 it is possible to see the majority of the streets and features that we can walk through today.

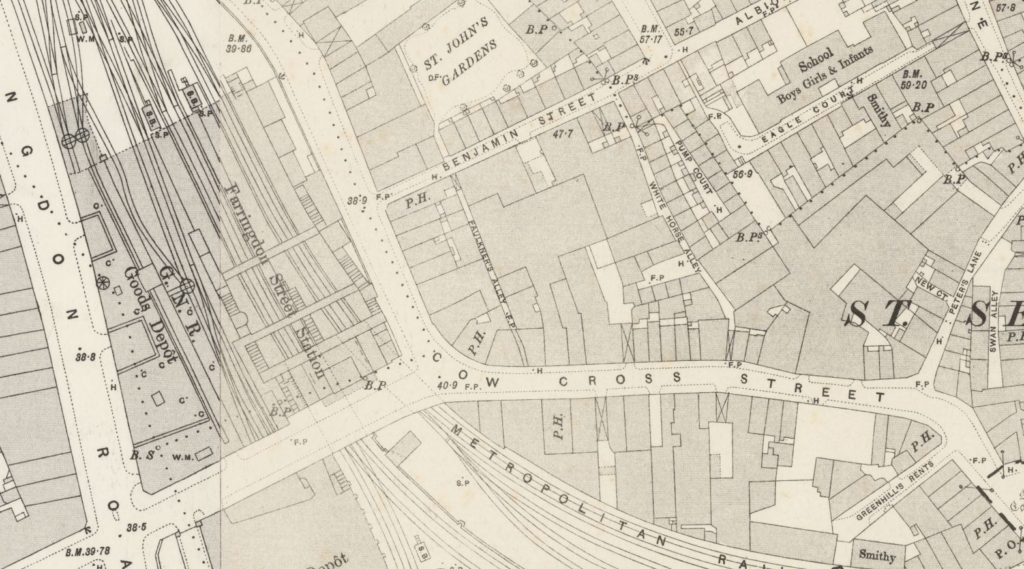

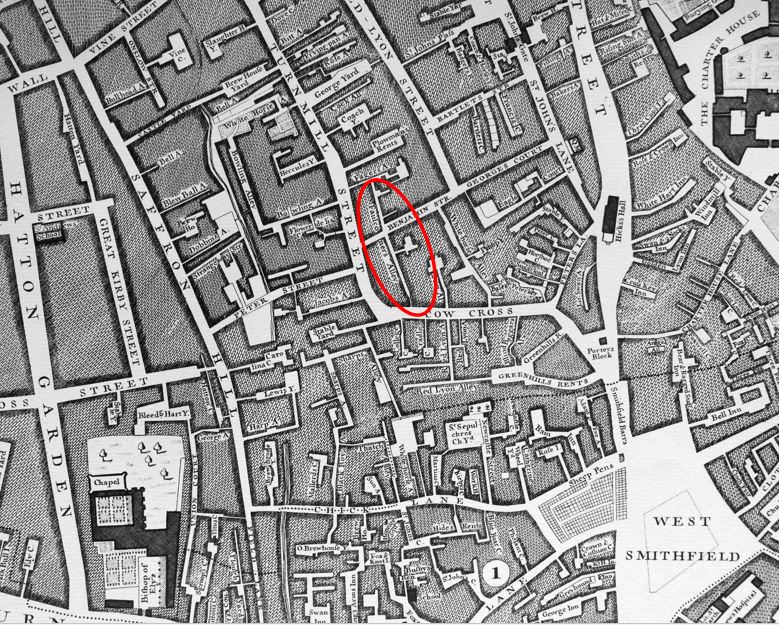

The following is an extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map and I have labelled the key features I will cover in the rest of this post.

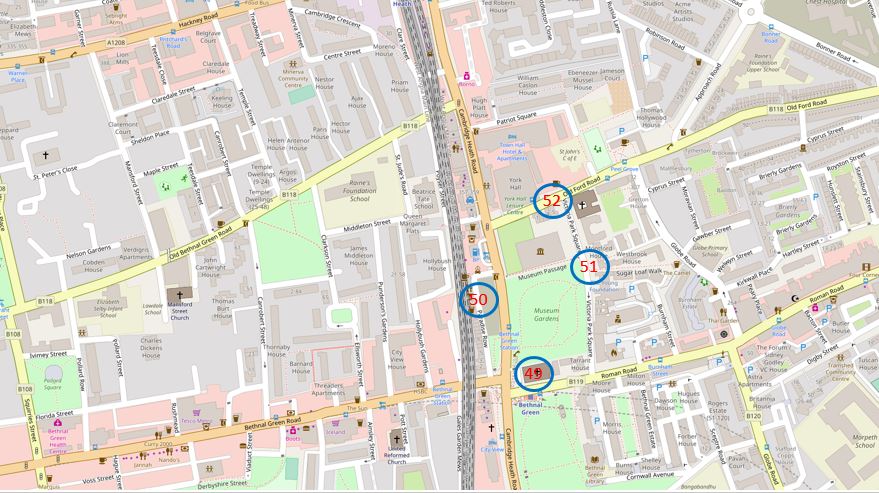

The area today, with the locations marked. Very different from the rural fields of 1746 (Map “© OpenStreetMap contributors”).

I travelled out to Bethnal Green on the underground and arrived at Bethnal Green Station which is at the junction of Roman Road, Bethnal Green Road and Cambridge Heath Road, and also located at this busy road junction is:

Site 49 – Soane’s St. John’s Bethnal Green

The church of St. John’s, Bethnal Green looks over this major road junction from the corner of Cambridge Heath Road and Roman Road.

The church was designed by Sir John Soane and built between 1826 and 1828.

One of the so called Commissioners Churches as the church was a result of the 1818 and 1824 Acts of Parliament which provided sums of money and established a commission to build new churches.

These were needed in the areas where there had been considerable population growth and Bethnal Green is a perfect example of the transformation of an area from a low population, rural landscape, to a densely populated urban settlement.

The location of the church was on open land directly adjacent to what was already a road junction in central Bethnal Green, however there are also references to there being a Chapel of Ease on the site, or close to the new church, (for example the Tower Hamlets publication: “History of parks and open spaces in Tower Hamlets, and their heritage significance” mentions a Chapel of Ease in 1617). The Roque map does show a building of some form in the road junction which may have been the Chapel of Ease, although this is just speculation at this point and needs some further research.

The church was damaged by fire in 1870 with much of the interior and the church roof being destroyed. The church was reopened the following year after restoration, which included new bells cast at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The church did suffer some damage during the last war, fortunately not the major level of damage suffered by many other east London churches.

The church was closed on the day of my visit, however it is good to see that the church is still an imposing building overlooking this busy junction, even on a grey and cold February morning.

Diagonally across the junction from the church is the Salmon and Ball pub:

Early references to the Salmon and Ball date the pub to the first half of the 18th century, however the current building dates from the mid 19th century and is Grade II listed. The earliest contemporary reference I could find to the Salmon and Ball is from a newspaper report on the 26th November 1795 reporting that:

“This day about two o’clock, in consequence of Advertisements, several thousand Weavers assembled near the Salmon and Ball, Bethnal Green, to take into consideration a Petition to the House of Commons against the Bill brought in by Mr. Pitt, to prevent the people from meeting, &c. Mr. Heron was called to the Chair, when several resolutions were passed and a Petition against the Bill agreed upon.”

There are newspaper references to an east London Salmon and Ball going back to the 1730s, but they do not specifically confirm that they refer to the pub in Bethnal Green.

The name of the public is interesting, I have only found one reference to the origin of the name. In the East London Observer on the 9th January 1915 in an article titled “Roundabout Old East London” by Charles McNaught, there is the following reference to the Salmon and Ball:

“The Salmon and Ball, by the bye, figures prominently in more than one historical scene in the turbulent days of Bethnal Green Weaverdom. Apart from that, however, it is a tavern sign sufficiently incongruous to awaken curiosity. The early silk mercers adopted the Golden Ball as their sign, because, in the Middle Ages all silk was brought from the East, and more particularly from Byzantium and the Imperial manufactories there. And at Byzantium the Emperor Constantine the Great adopted a Golden Globe as the emblem of his imperial dignity. The Golden Ball continued as the mercer’s sign until the end of the Eighteenth Century and then it gradually passed to the ‘Berlin’ wool shops, and – conjoined with a fish or other animal – its was favourite sign for Taverns in the silk weaving area.

The Salmon and Ball in Bethnal Green is not the only house with that sign; and other local names of the past include: The Ball and Raven, The Green Man and Ball, the Blue Balls, The Ring and Ball, and many others.”

No idea if this is the true origin of the name, but an interesting possibility.

My next stop was very close, and it was a short walk to:

Site 50 – Early 19th Century Terrace

This location was just opposite the church, a narrow street that runs parallel to Cambridge Heath Road and that goes by the name of Paradise Row. For the main part of the street, houses run along one side, with the opposite side formed by Paradise Gardens, which in February really did not live up to the name.

The terrace of houses in Paradise Row taken from within Paradise Gardens:

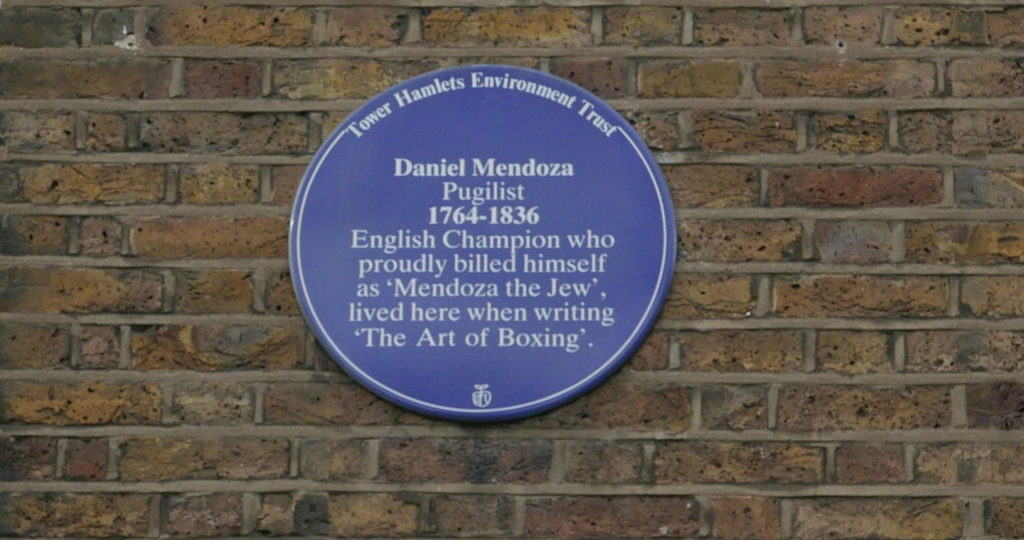

There is a blue plaque on one of the houses recording that Daniel Mendoza lived in the house:

Daniel Mendoza was a fascinating character. A boxer, or pugilist who became heavyweight champion between 1792 and 1795. In an age when it was common to advertise yourself with a memorable name. As the plaque states he proudly billed himself as ‘Mendoza the Jew’ in honour of his Jewish heritage. For an example of how other boxers billed themselves, Mendoza’s first recorded successful prize fight was against the wonderfully named ‘Harry the Coalheaver’.

The plaque refers to Mendoza living in Paradise Row when he was writing ‘The Art of Boxing‘. In the 18th century, boxing was mainly a punching, grappling, gouging match between two fighters.

Mendoza advocated a more formal, scientific approach to boxing which he set out in his book ‘The Art of Boxing‘. In his preface to the book, Mendoza explains his approach and the reasons why boxing should have a more scientific method:

“After the many marks of encouragement bestowed on me by a generous public, I thought that I could not better evince my gratitude for such favours, than by disseminating to as wide an extent, and at as cheap a rate as possible, the knowledge of an ART; which though not perhaps the most elegant, is certainly the most useful species of defence. To render it not totally devoid of elegance has, however, been my present aim, and the ideas of coarseness and vulgarity which are naturally attached to the Science of Pugilism, will, I trust, be done away, by a candid perusal of the following pages.

Boxing is a national mode of combat, and as is peculiar to the inhabitants of this country; as Fencing is to the French; but the acquisition of the latter as an art, and the practice of it as an exercise, have generally been preferred in consequence of the objection which I have just stated as being applicable to the former.

The objection I hope, the present treatise will obviate, and I flatter myself that I have deprived Boxing of any appearance of brutality to the learner, and reduced it into so regular a system, as to render it equal to fencing, in point of neatness, activity, and grace.

The Science of Pugilism may, therefore, with great propriety, be acquired, even though the scholar should feel actuated by no desire of engaging in a contest, or defending himself from an insult.

Those who are unwilling to risque any derangement of features in a real boxing match, may, at least, venture to practice the Art from sportiveness and sparring is productive of health and spirits as it is both an exercise and an amusement.

The great object of my present publication has been to explain with perspicuity, the Science of Pugilism, and it has been my endeavour to offer no precepts which will not be brought to bear in practice, and it will give me peculiar satisfaction and pleasure to understand, that I have attained my first object, by having taught any man an easy regular system of so useful an Art as that of Boxing.”

Daniel Mendoza put his approach into practice throughout his career. He was highly successful and his name became very well known across the country. He made (and lost) a considerable sum of money.

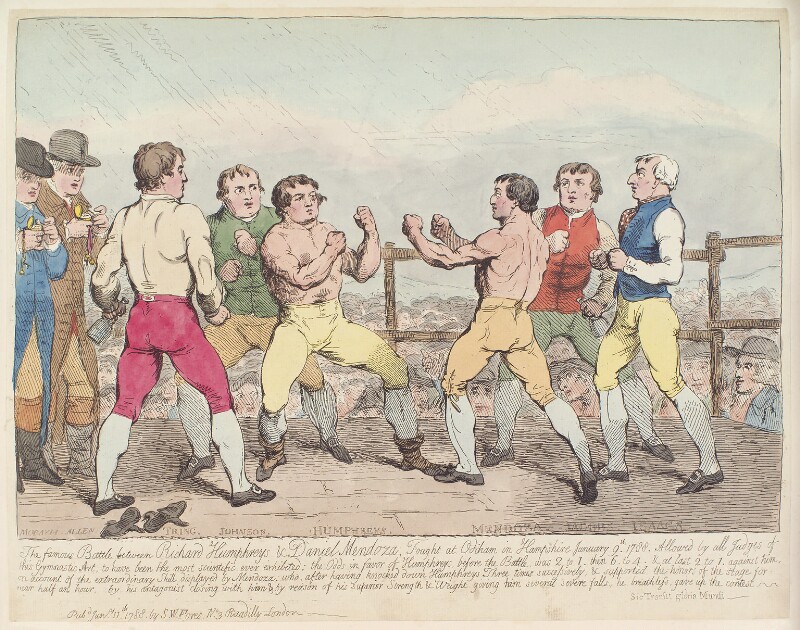

His most famous fights were against Richard Humphreys, his former trainer and mentor. These fights were captured in a series of etchings (©Trustees of the British Museum), published very soon after the fights.

In the following we see the first fight held on the 9th January 1788 in Odiham in Hampshire

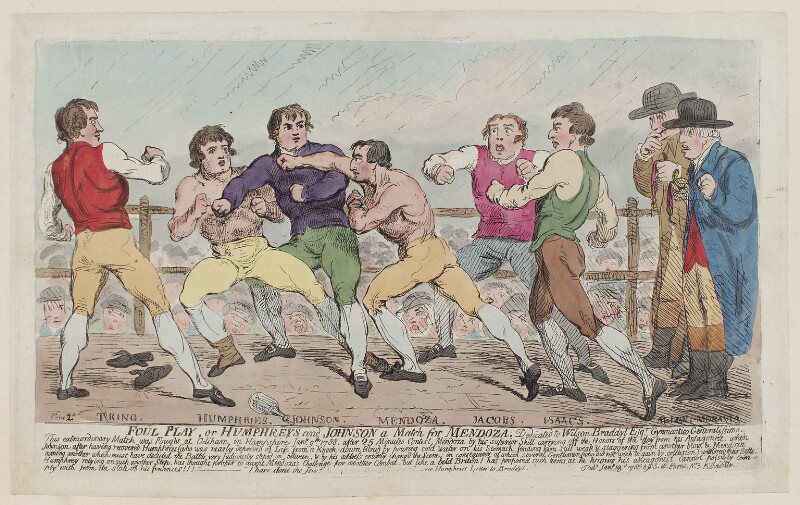

Mendoza lost the fight and the following etching “Foul Play” shows how Mendoza lost the fight through the actions of Tom Johnson, Humphreys second, who blocked a blow from Mendoza:

In perhaps an early version of the tension built up in advance of fights today, in the 18th century Mendoza and Humphreys traded insults and accusations at each other through a series of letters published in newspapers across the country.

In a letter written on the 16th January 1788 when Mendoza was living in London at No. 9, White Street, Houndsditch, Mendoza set forth three propositions for how the next fight should take place. He finishes the letter with:

“The acceptance or denial of Mr. Humphries to the third proposition, will impress the public with an additional opinion of his superior skill, or they must conclude that he is somewhat conscious of his inferiority in scientific knowledge. In imitation of the challenge of Mr. Humphries, I shall not distress him for an immediate reply, but leave him to consult his friends, and his own feelings, and send an answer at his leisure.”

Mendoza wrote a follow up letter on the 27th January 1788:

“To prevent the tedious necessity of a reference to the several letters which I have written, and which have appeared in your paper, I am induced to take my leave of the public, with the insertion once more of the conditions of my challenge to Mr. Humphreys, and I beg that the world will consider them as open to the acceptance of that gentleman, whenever he may think better of his boxing abilities.

The first condition is, that I will fight him for 250 guineas a side, the second, the victor to have the door, the third, the man who first closes to be the loser, fourth and last, the time of fighting to be in the October Newmarket meeting.

Mr. Humphreys would do well to insert this challenge in his private memorandum-book; and as a teacher of the art of boxing, it would not be amiss to have it penned, neatly framed, and hung up in his truly scientific academy.”

Letters continued and finally Humphries accepted the challenge, writing on the 31st July 1788:

“I have seen your letter, and accept your challenge. I am glad that you have at last found out your own mind. The terms shall be settled at a meeting which I will appoint by private letter to you.”

After the loss of the first fight, Mendoza won the next two fights. The following etching shows what looks to be the closing stages of the fight on the 6th May 1789 with Mendoza on the left and a collapsing Humphreys on the right.

After his boxing career declined in the 1790s, Mendoza pursued a number of other money making opportunities including landlord of the Admiral Nelson in Whitechapel, the occasional boxing match, running his own academy, and also what today would probably be classed as a ‘bouncer’ at the Covent Garden Theatre.

The theatre management were attempting to increase ticket prices, which resulted in riots and protests in the theatre.

“It is a notorious fact that the Managers of Covent-Garden Theatre have both yesterday and today furnished Daniel Mendoza, the fighting Jew, with a prodigious number of Pit Orders for Covent-Garden Theatre, which he has distributed to Dutch Sam, and such other of the pugilistic tribe as would attend and engage to assault every person who had the courage to express their disapprobation of the Managers’ attempt to rain down the new prices.”

In another newspaper report, Daniel Mendoza was reported as being at the head of “150 fighting Jews and hired Braizers, as Constables.” His actions supporting the theatre management did not help his popularity with Londoners as he was seen to be supporting the theatre management rather than the common theatre goer.

I can find very little information on Daniel Mendoza’s family. He appears to have had two sons and a daughter. One son also named Daniel (so presumably the eldest son) appears in a number of newspaper reports accused of robbery and also wounding a man with a penknife.

In another newspaper report, his married daughter along with another woman were reported as being assaulted by two cab drivers.

Daniel Mendoza died in September 1836. his lasting legacy were the changes to boxing through his approach to ‘scientific boxing’ which started the move of boxing towards a rules based sport.

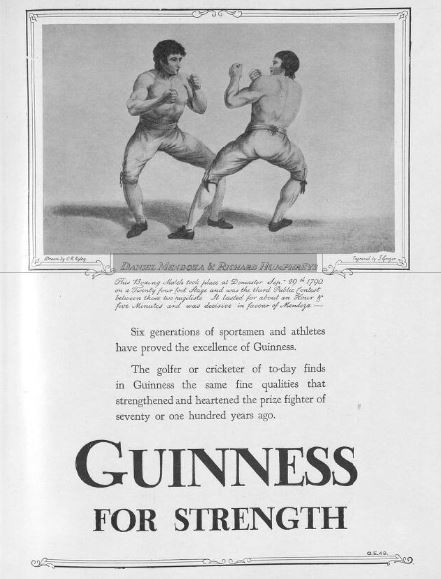

The contest between Daniel Mendoza and Richard Humphreys was still being used as an example of sporting excellence many years later, as shown in this Guinness advert from 1960:

The view from Mendoza’s house on Paradise Row must look very different today, with the volume of traffic on the Cambridge Heath Road, but good to see this terrace of houses still standing.

To get to my next location, I walked along the Cambridge Heath Road, passing the V&A Museum of Childhood, then turned into Old Ford Road, opposite this mix of buildings, including the Dundee Arms pub:

Along Old Ford Road is the York Hall leisure centre, swimming pool and in a link with Daniel Mendoza once one of Europe’s most significant boxing venues:

To the right of York Hall was part of my next location:

Site 52 – 17th Century Nettleswell House With Adjoining Late 18th Century Terrace: Across Road, Early 18th Century Terrace

This is the early 18th century terrace, across the road from Nettleswell House on Old Ford Road:

To get a view of Nettleswell House I turned off Old Ford Road into Victoria Park Square. It was difficult to get a good view of the buildings as they are concealed behind a tall brick wall, however they look in fine condition.

Nettleswell House is a Grade II listed building. The listing states that the building is late 17th century with early 18th century alterations.

There must have been an earlier building on the same site, with the same name as the listing also records what is on the plaque, just visible on the house in the above photo “Netteswell House – AD1553 – Remodelled 1705 and 1862″

In my post on “New Deal For East London – Stepney Green” I found one of the buildings built by the East End Dwellings Company – Dunstan House on Stepney Green. Walking along Victoria Park Square I found another. Montford House was built by the company in 1901, two years after the Stepney Green building.

The name apparently is a reference to Simon de Montford and there are stories that he was blinded at the Battle of Evesham 1265 and became a beggar in Bethnal Green (the same story is sometimes given as the source of the name of the Blind Beggar pub).

In reality, Simon de Montfort was killed at the Battle of Evesham and was buried at Evesham Abbey, along with Henry, one of his sons. His other son, also called Simon did arrive in Evesham, but too late to help the cause of his father. He later escaped to France.

There are a good number of the buildings of the East London Dwellings Company remaining. One of my ever growing list of projects is to map and photograph all their buildings.

Further along Victoria Park Square, I found my next location:

Site 51 – 1700 Group Behind Gardens

Along one side of Victoria Park Square is a magnificent group of buildings, all in good repair, and as indicated by the Architects’ Journal title for these buildings, they all stand back from the street, separated by a good sized front garden.

Some include some rather ornate ironwork between street and garden:

The terrace:

There is some fascinating architecture along this one street, including what looks to have once been a private chapel built as a rather strange extension to the house behind:

Finding this terrace was the last of four locations in Bethnal Green. I then walked down to Stepney, so to complete the post, here are some of the buildings to be found on the route from Bethnal Green to Mile End Road, along Cambridge Heath Road.

This building is along Roman Road, alongside Bethnal Green Gardens.

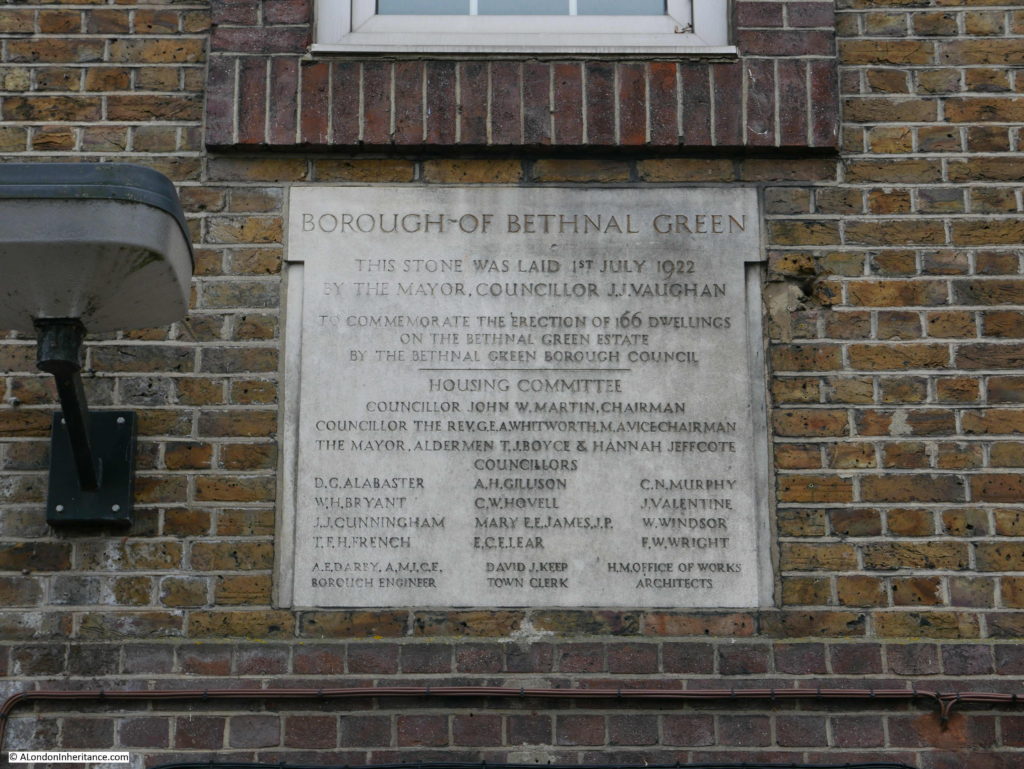

The building is Swinburne House and it demonstrates the change during the early decades of the 20th century from housing built by philanthropic organisations such as the East End Dwellings Company to council built properties.

A stone on the front of the building records that the stone was laid on the 1st July 1922 to commemorate the erection of 166 dwellings by Bethnal Green Borough Council. The names of the housing committee are also recorded.

Along Cambridge Heath Road is this closed factory building, Moarain House:

I believe that this was the factory of umbrella manufacturers Solomon Schaverien. Many of their umbrellas include a label with the name Moarain on the inside of the umbrella.

I would not be surprised if the factory was replaced by an apartment building in the next few years.

Just after Moarain House, the railway from Liverpool Street Station crosses Cambridge Heath Road. All the railway arches along Malcolm Place have been closed off, and the typical businesses that normally occupy railway arches (car wash, car repair, tyres, light manufacturing etc.) have all moved out.

Network Rail are planning to redevelop these arches and the application for planning permission submitted to Tower Hamlets Council shows a row of arches with glazed brick for the piers, glass and stainless steel fascia – very different to the arches as they are now.

The proposed use of the arches are as a cafe, restaurant, drinking establishment, retail, light industrial and warehousing. No doubt increasing revenue for Network Rail, but another loss of the traditional use of railway arches by small businesses in East London.

After passing under the railway I was soon at Mile End Road for the locations in my previous post. It was good to see that all the sites listed in 1973 are still to be found in Bethnal Green, and in good condition.

I find these walks fascinating not just by seeing if the sites listed in the Architects’ Journal have survived, but also the chance finds along the way, and in this walk opening a window on the world of boxing in the late 18th century, another building by the East London Dwellings Company and the evolution from charity to council construction of homes.

I am now almost through all 85 sites listed in 1973, just a couple of groups of buildings to visit, in Greenwich and the area running north and west along the River Lea / Bow Creek. Hopefully these walks will not be as windy and cold as my walk through Bethnal Green.