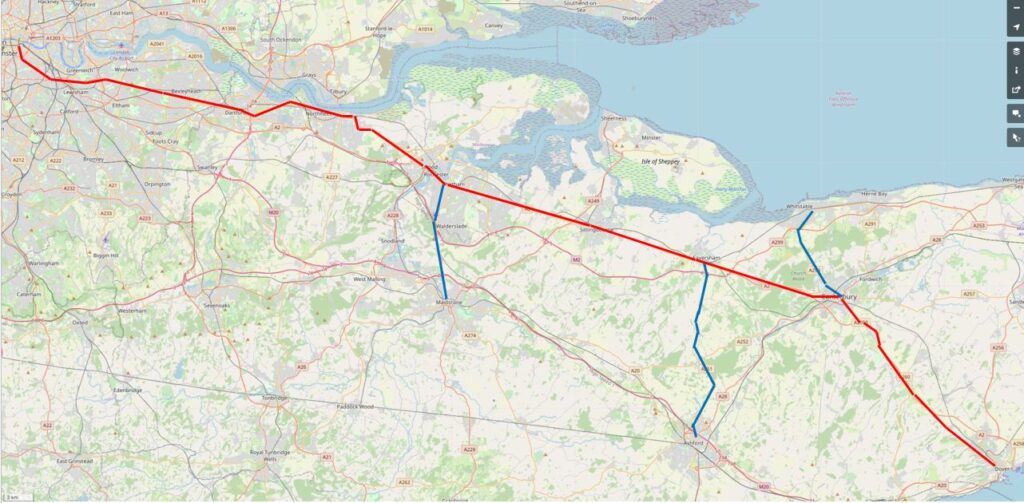

If you have a gas boiler or cooker, the chances are that the gas you use could come from the North Sea, Norway, or via ship carried liquefied natural gas from countries such as Qatar, Russia and Trinidad to the terminal on the Isle of Grain in the Thames Estuary. When gas started to be used as an energy source in the 19th century, the production of gas was very local to consumers, and for this week’s post I am exploring one such production facility, the Rotherhithe Gas Works.

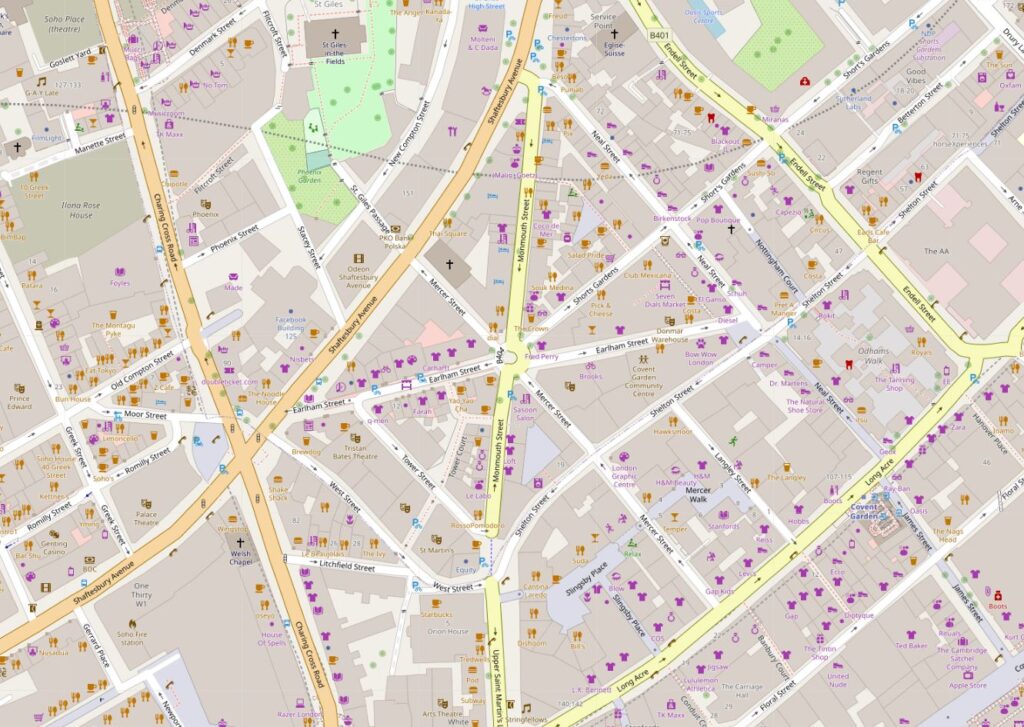

I have marked the location for today’s post by the red star in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

That is not a bridge across the Thames at the point of the star, it is the way Openstreetmap shows the Rotherhithe Tunnel.

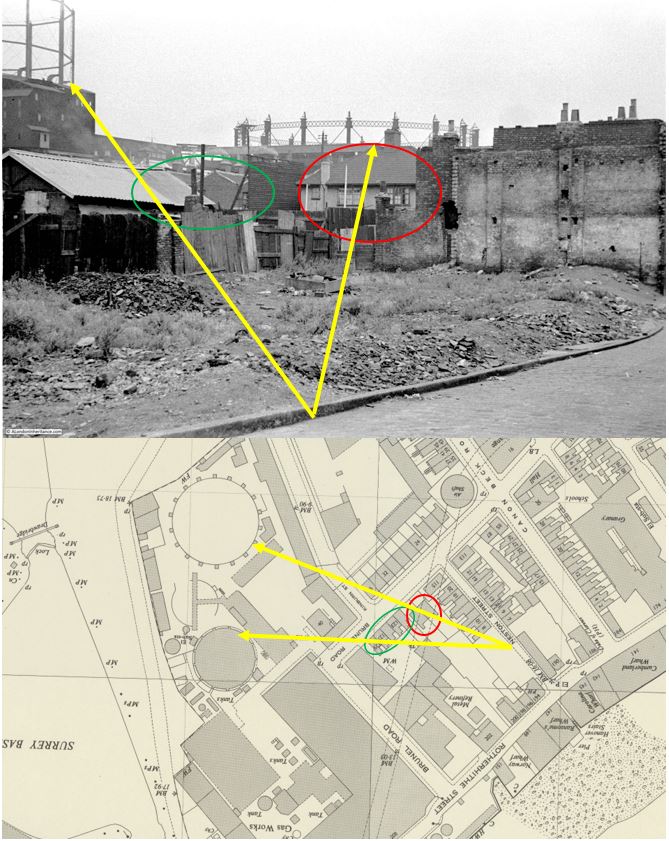

The reason for the post on the Rotherhithe Gas Works is because of a photo taken by my father in 1948. The following photo shows what is probably open space following the demolition of bomb damaged houses, with in the background, parts of two large gas holders.

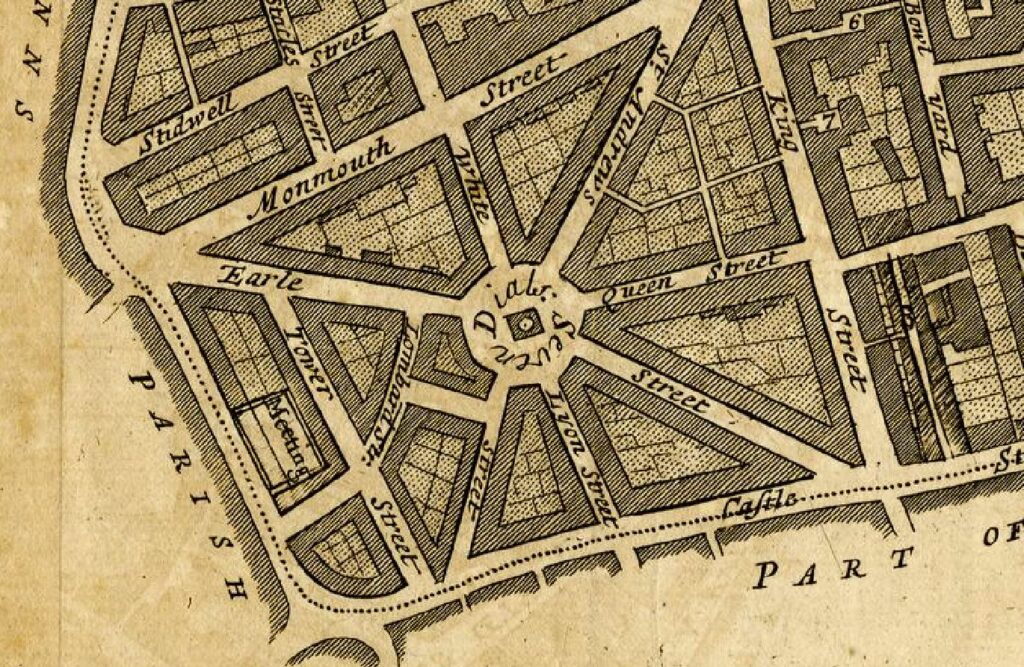

I wanted to find the location of the photograph. I knew from my father’s notes that the location was Rotherhithe, but not from where the photo had been taken. The two gas holders were obvious clues, however the area is very different today, so I started off with the 1950 edition of the Ordnance Survey map of the area.

I have copied the photo below, added the map extract and marked up key points shown in both photo and map, and the approximate location where my father was standing to take the photo. I needed to rotate the map to get a similar orientation to the photo, so north is at the bottom and south at the top of the map.

The red oval marks a semidetached pair of houses. To the left of these houses, there appears to be a tall wooden fence, and next to the fence, a terrace of older houses (you may need to click on the photo and enlarge to see the details of these clearly). These are the terrace houses shown by the green oval on the map.

In the background are the two large gas holders. The one on the right appears to be a larger circumference than the holder on the left, which matches both photo and map. Part of the gas holder on the left is obscured by a large building, again the same in both photo and map.

Extending the alignment of these features back, and they converge at a point on a street which again aligns with the photo as part of a street is in the lower right corner.

Rotating the map back to the correct orientation, and the street is Neston Street, marked below with the red star. The terrace of houses on the right of the street ends in a blank space on the map which corresponds with the 1948 photo (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

So it should be simple to find the location today? Not very, as the area has changed so much. In the 1950 map above, All the large buildings between the round gas holders and the River Thames at top left, were part of the Rotherhithe Gas Works. To the left, there was some housing, along with other industrial buildings, and the area had also suffered bomb damage.

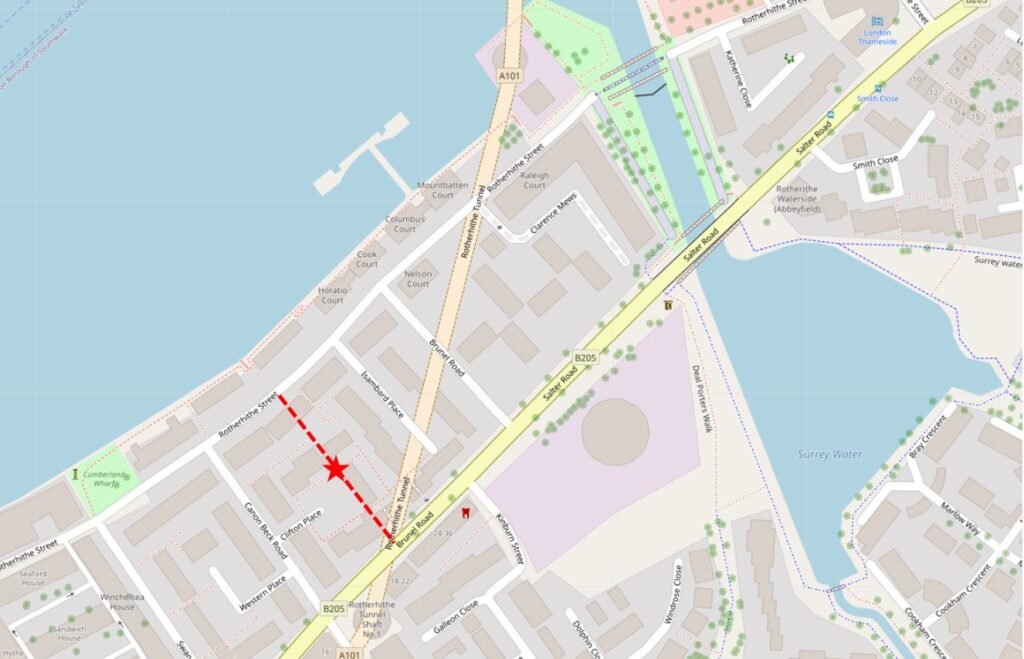

The Rotherhithe Gas Works closed in 1959, and over the last few decades, the area has been considerably redeveloped with new housing now covering all the original site of the gas works (with one exception). Roads have changed, and Neston Street has disappeared.

Marking Neston Street on today’s map of the area (red line) allows the location of the 1948 photo to be identified (red star),

I needed to visit the site to see the area today, and to find one of the two remaining elements of the Rotherhithe Gas Works infrastructure, one that may not be around for too much longer.

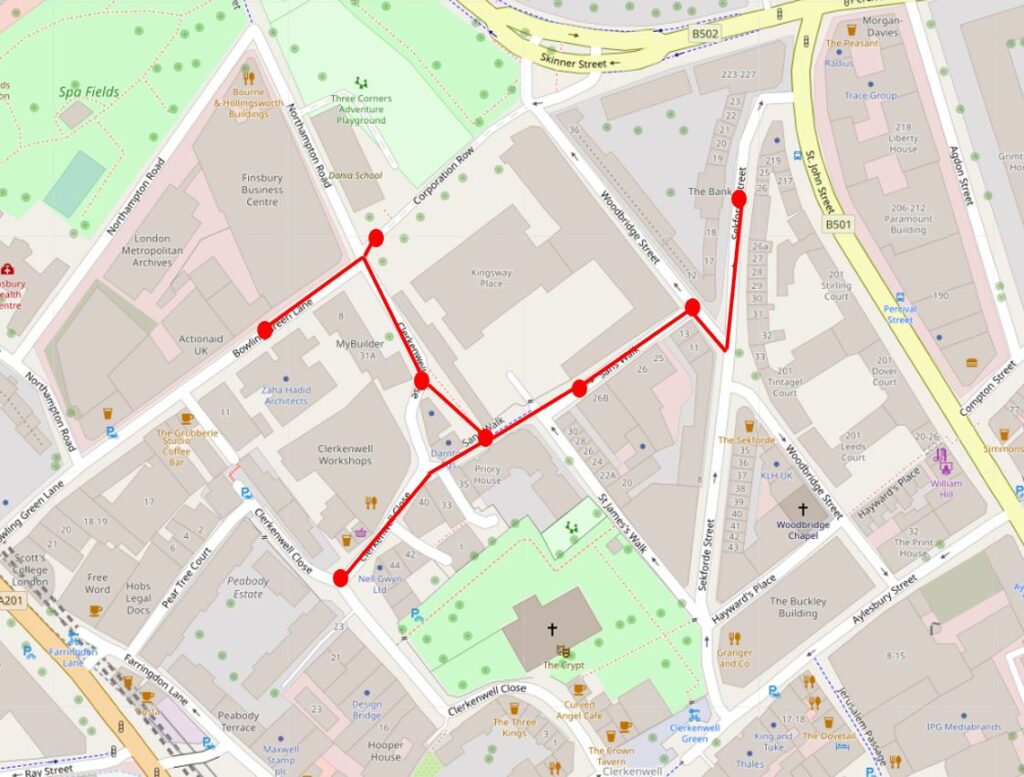

I walked along Rotherhithe Street from the west, and walked up Canon Beck Road (to the left of the red line), a road that appears on both today’s and the 1950 map.

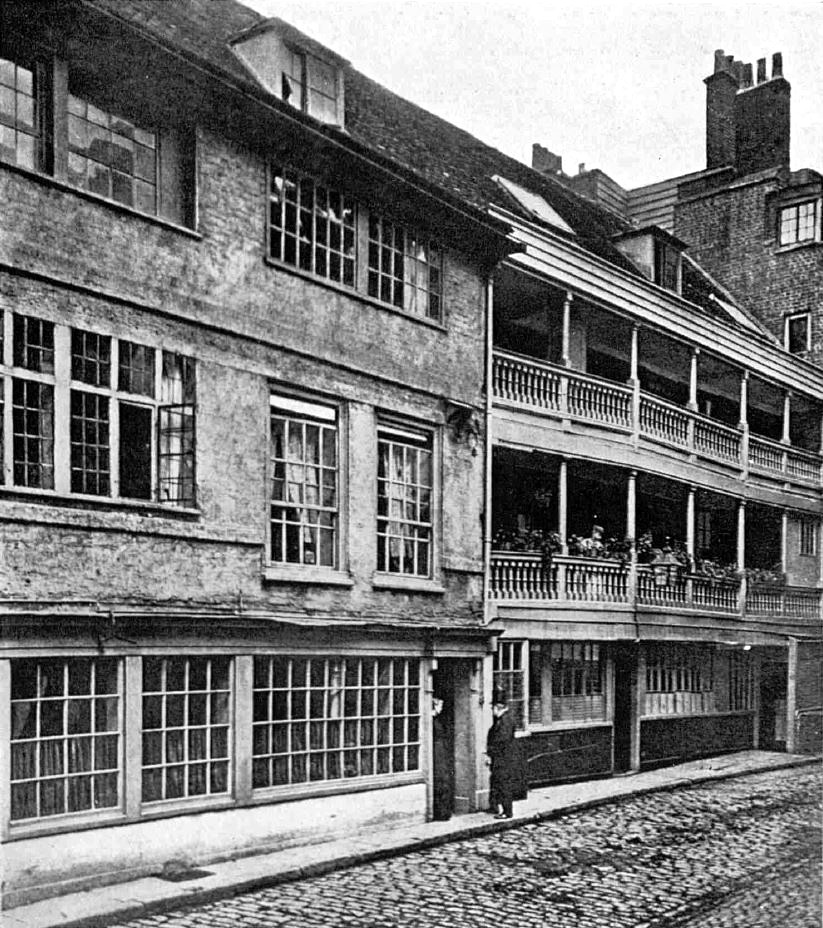

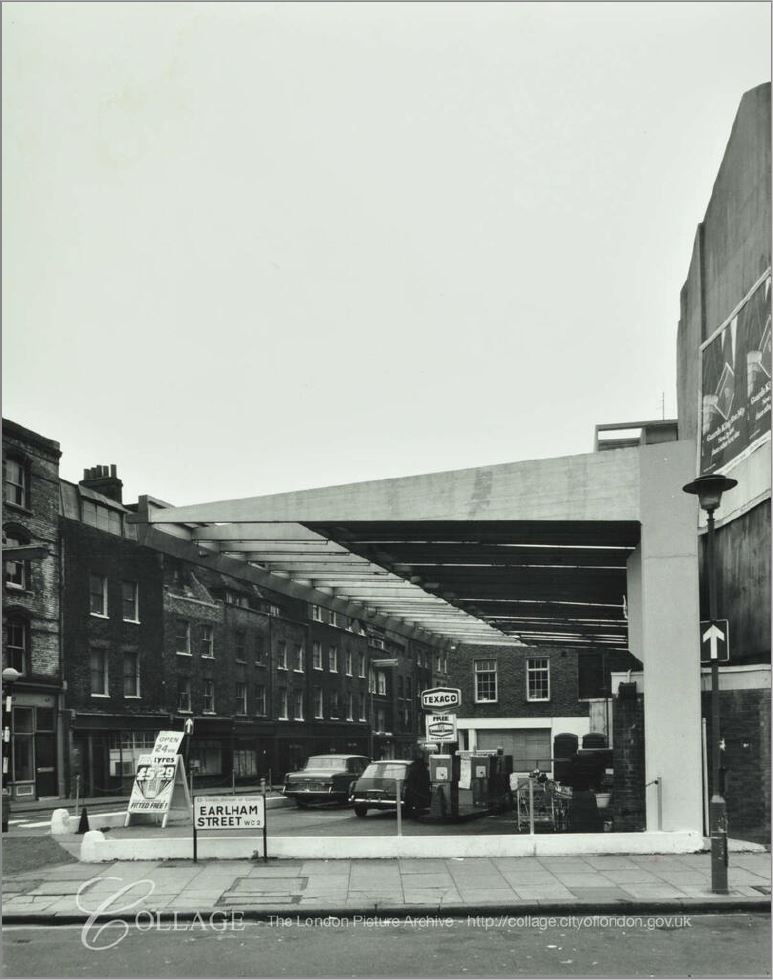

Just over half way along Canon Beck Road is a short entrance road to a residential square, Clifton Place. This is shown in the photo below:

Neston Street would have run, left to right along the front and over part of the houses at the far end of the photo. To take the 1948 photo, my father was probably standing somewhere around the green and blue bins to the left of the photo.

Looming in the back of the above photo is one of the two remaining parts of the Rotherhithe Gas Works – the gas holder also seen to the left of the 1948 photo.

As well as visiting the site of my father’s photo, the gas holder was the second reason for wanting to visit, as it may well be soon disappearing as a local landmark, and a reminder of the industrial history of this part of Rotherhithe.

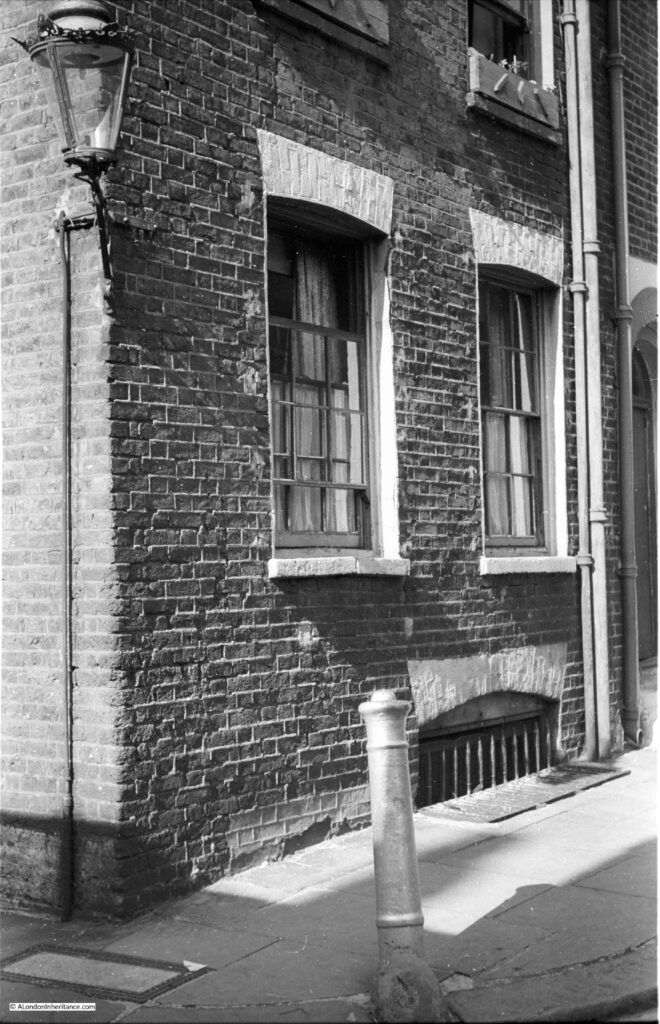

I walked up to Brunel Road. The terrace of houses along Brunel Road are not part of the redevelopment of the last few decades, they are much earlier. The gas holder can be seen in the background.

Walking along Brunel Road up to the location of the gas holder, to find the one remaining holder from the gas works, sitting in the space that was also once occupied by the second gas holder in the 1948 photo.

The remaining gas holder may not be here for long. Plans have been submitted for a complete redevelopment of the site which includes the land occupied by the gas holder, and the surrounding land.

The work will involve the demolition of the gas holder, and the infill of the tank below the gas holder, and the tanks below ground of the gas holders that have already been demolished.

Considerable work will involve removing contamination of the land and the move of operational gas piping and controls that still occupy the site.

The current plans appear to cover the construction of:

- 40 dwellings for social rent

- 39 dwellings for discount market rent

- 198 private dwellings

The plans include the intention “To celebrate the character of the site and its industrial heritage”, which as far as I can see runs to “Balconies and stairways take reference from the industrial metal work” and “Pitched roofs reference the storage sheds associated with the Surrey Water Docks” along with the use of the colour red to accentuate certain features to recall the colour of the existing gas holder.

There is a web site for the proposed development, which includes presentations on the proposed work. It can be found under the name of the development Rotherhithe Holder Station.

A view of the gas holder and the surrounding land which is in-scope of the proposed development:

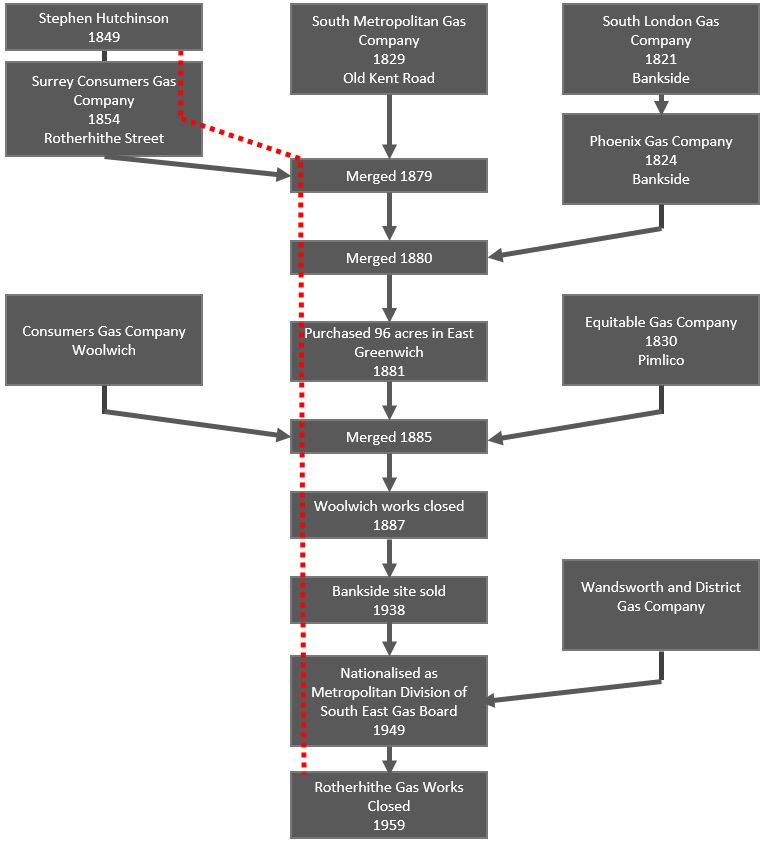

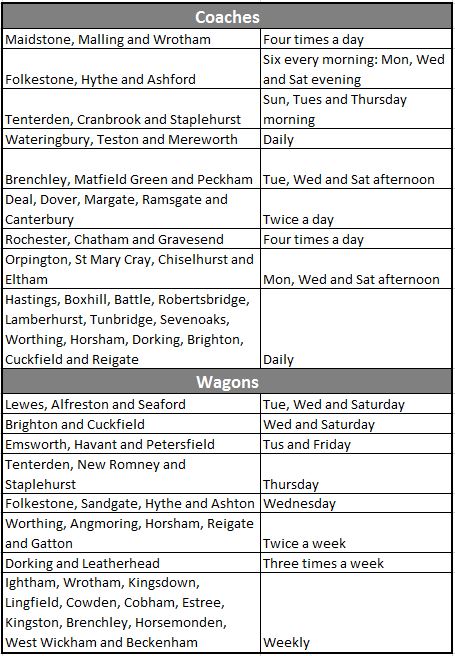

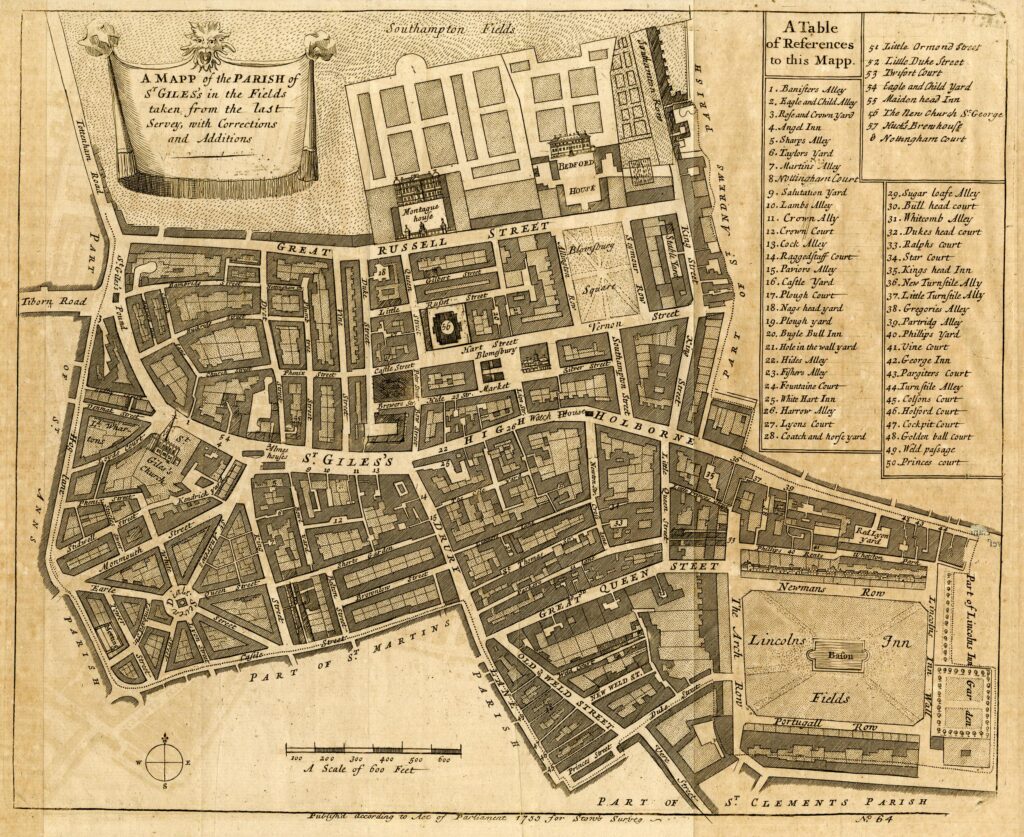

The history of the Rotherhithe Gas Works is complex, and tells the story of the consolidation of the local gas companies throughout the 19th century and nationalisation in the 20th century.

Using a number of resources (which I will list at the end of the post), I have attempted to put together a graphical history of the Rotherhithe Gas Works, their ownership, and mergers with other gas companies. Be aware that there are various conflicting dates for some events, and also definition of a date, for example when a gas works became operational, the incorporation of a company by Act of Parliament etc.

Any corrections would be appreciated.

The following graphic shows how the Rotherhithe Gas Works (starting at left and highlighted by the red dotted line) integrated with London’s gas companies through to closure in 1959.

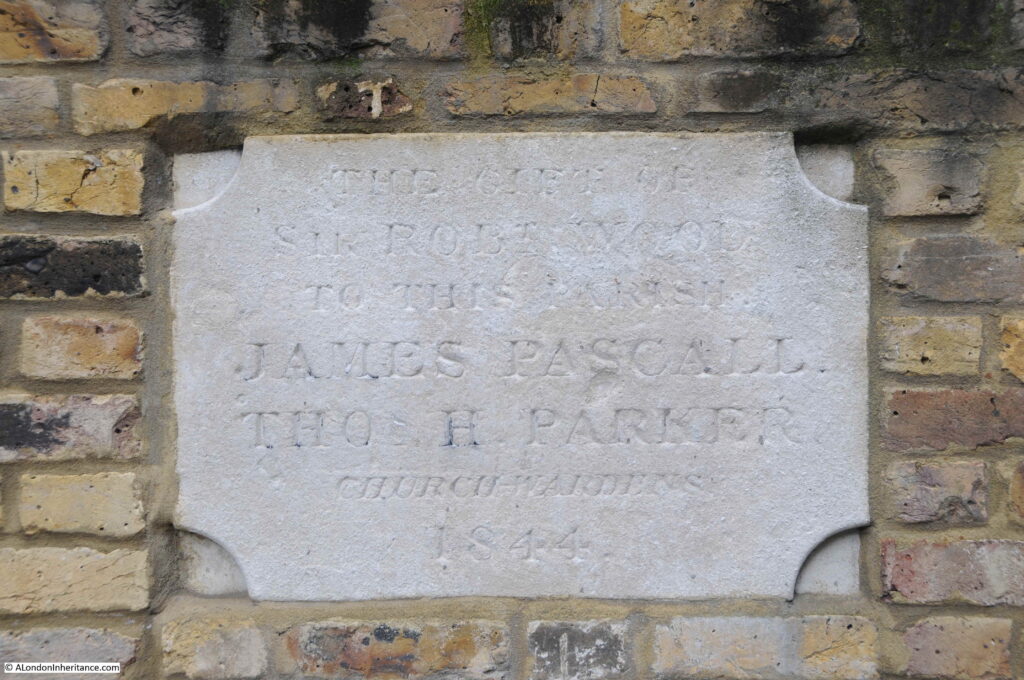

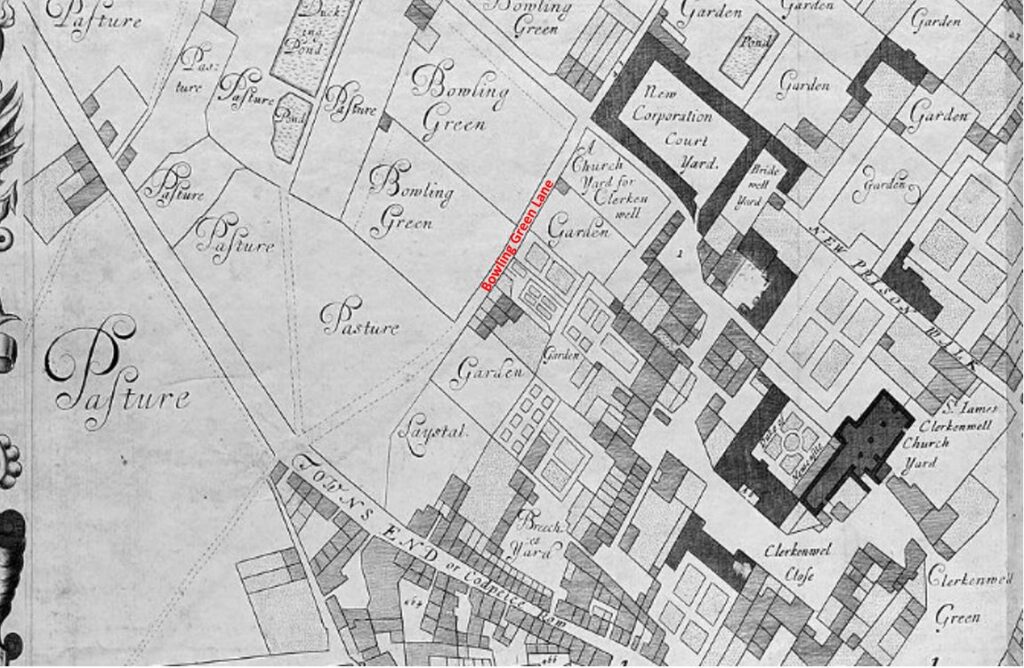

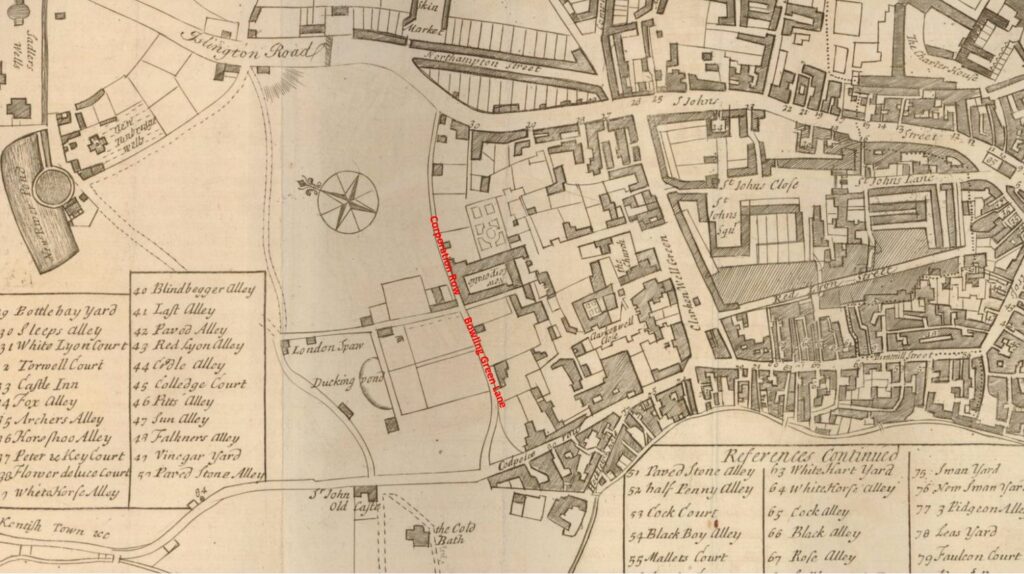

The first gas works in Rotherhithe seem to have commenced construction by Stephen Hutching in around 1849, with the works becoming part of the Surrey Consumers Gas Company, a company incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1854.

In the mid 19th century there were many concerns about the quality of the gas provided to consumers and the cost, with companies having a monopoly within their local supply area. An 1849 article in The Era titled “Gas Monopolists In A Fever” talks about the need for gas companies who can supply gas “free from sulphureted hydrogen, acid and ammonia” and the extortionate price charged with upwards of 15 shillings per 1,000 cubic feet, where independent calculations estimate that gas can be produced using modern methods for 2 shillings per 1,000 cubic feet.

The Surrey Consumers Gas Company merged with the South Metropolitan Gas Company in 1879, which brought together two gas companies serving south and south east London.

In 1881, the South Metropolitan purchased a large area of land on the Greenwich Peninsula and started the construction of the gas works which would go on to be one of London’s major gas producing centres for many years.

The South Metropolitan Gas Company would continue to integrate other, smaller companies, including the Phoenix Gas Company based in Bankside in 1880, the Consumers Gas Company in Woolwich and the Equitable Gas Company in Pimlico, both in 1885.

Probably because of the growth of sites such as the Greenwich Peninsula and Rotherhithe, the South Metropolitan closed and sold off sites at Woolwich and Bankside.

Reading newspaper references to London’s gas companies throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, there are very many references to the monopoly position of these private companies, the cost of gas and frequently the quality of the gas, and pollution from the gas producing works.

In January 1860 the Surrey Consumers Gas Company were at Southwark Police court being charged by the Bermondsey vestry under the Nuisance Removal Act “for that they, in the manufacture of gas on their premises at Rotherhithe, did, on or about the 16th inst. cause an intolerable nuisance to exist as to be dangerous and injurious to the inhabitants of the parish of Bermondsey”.

The issue in January 1860 seems to have been a considerable amount of ammonia in the gas supply which had not been removed by the purifiers at the Rotherhithe gas works, and was causing a very bad smell, and health problems to those in Bermondsey who consumed the gas.

In 1875 at the half yearly meeting of the Surrey Consumers Gas Company, the news reports stated that the meeting “must have been attended with considerable interest by the fortunate individuals who hold shares therein. They have been too long accustomed to their unfailing profit of 10 per cent per annum. The balance sheet was as good as had ever been issued by the company”.

Consumer groups were frequently formed and south London’s vestries were often complaining about the costs and quality of gas, and there were many arguments that such companies should be publicly rather than privately owned.

London’s gas consumers would have to wait until 1949 for this to happen, when the countries gas companies were nationalised by the post war Labour government and the South Metropolitan Gas Company along with other London gas companies were merged into local gas boards under public ownership.

Ownership of gas provision came full circle when the nationalised gas board was privatised in 1986 as British Gas, and since then many of the arguments about the cost of gas are very similar to those in 19th century newspapers.

The production of gas was a very dirty business. Coal was heated in a furnace, which produced a range of gases including hydrogen and carbon monoxide. These gases were passed through a condenser where solids and liquids such as tar would be removed, before passing through a purifier where impurities such as sulpher and ammonia would be removed.

The gas was then fed to the gas holders ready for distribution at pressure to gas consumers.

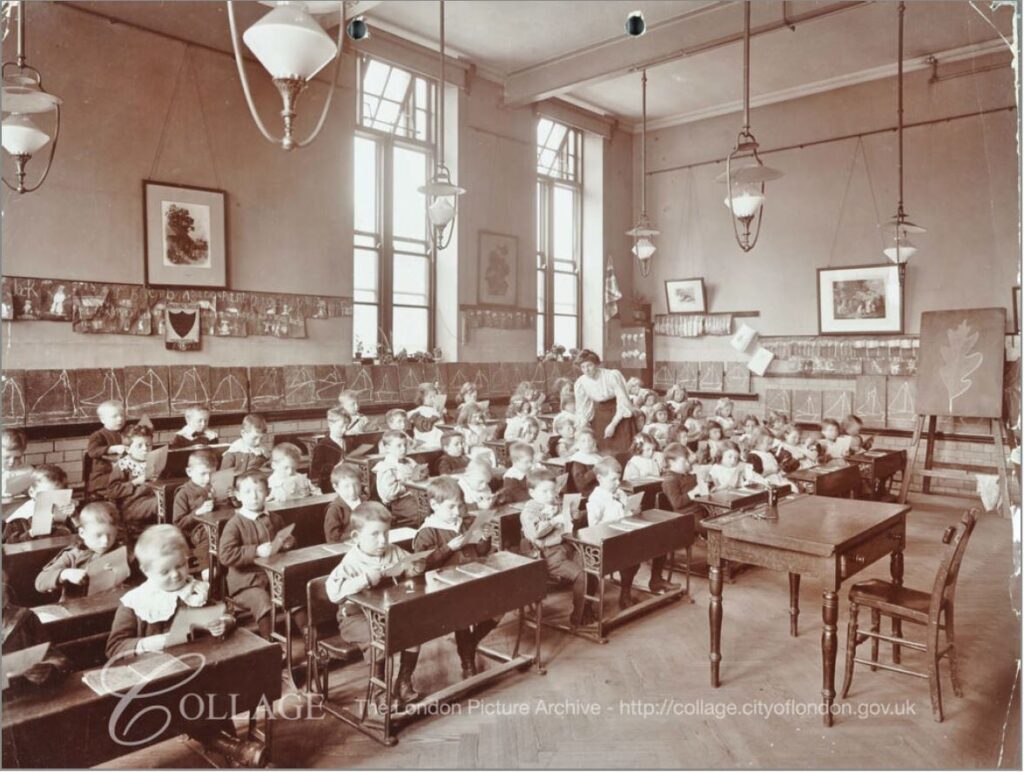

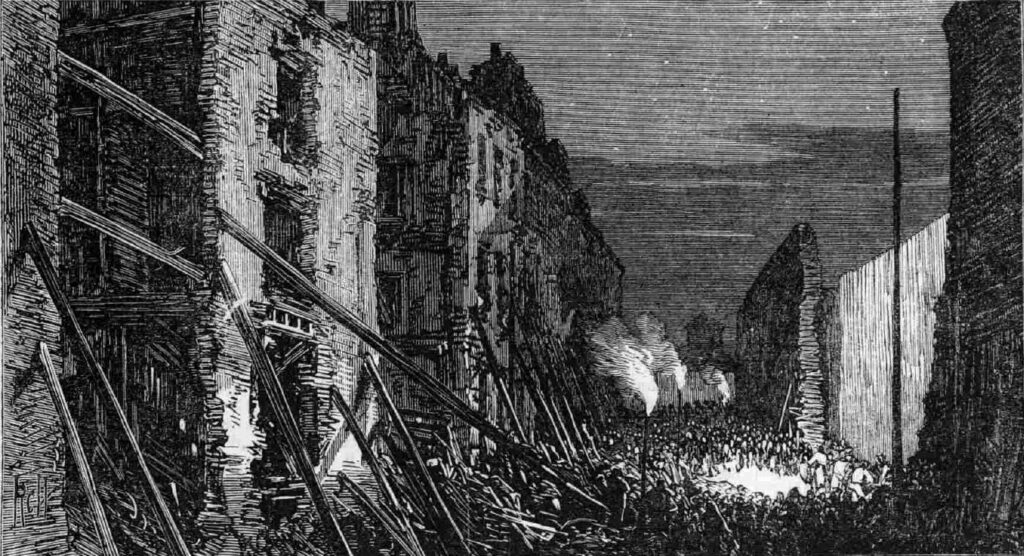

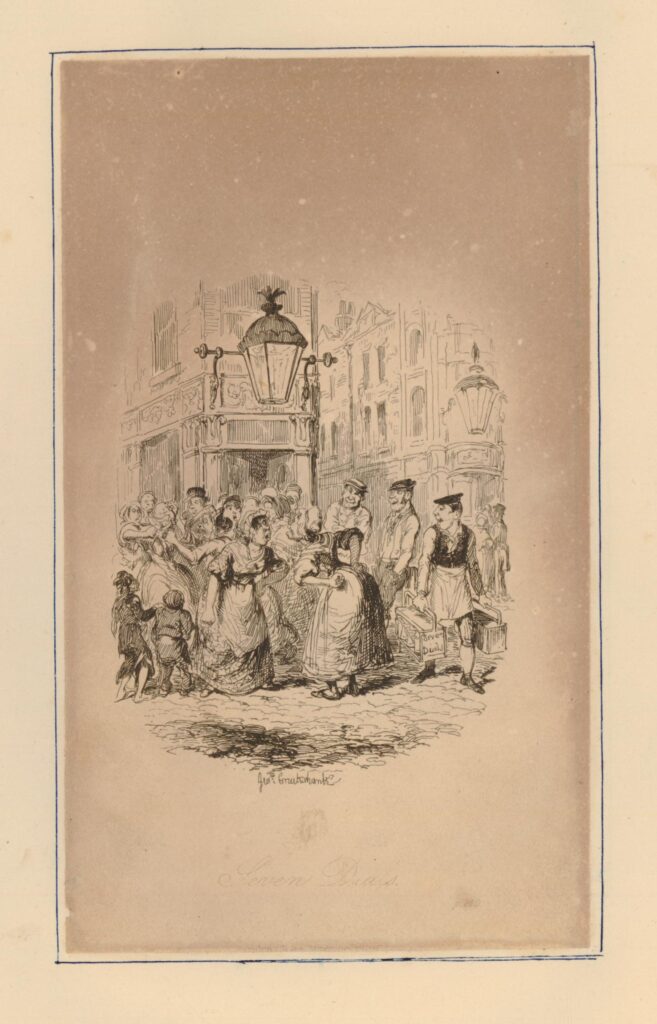

An impression of the interior of the Rotherhithe Gas Works can be had from the following artwork dated 1918, with women working in the “retort” area (retorts are the furnaces where coal was heated to produce gas).

Work at the Rotherhithe gas works was dangerous and there are newspaper accounts of accidents within the works. For example, when one of the gas holders was being built in 1890, a labourer named Barnes, aged 23, working for the contractors Clacton & Son of Leeds, died after falling twenty feet to the base of the holder.

Workers at the gas works had the Rotherhithe Gas Works Institute, and in October 1894, five crews from the institute raced on the Thames from the coal jetty at the gas works to Deptford Creek.

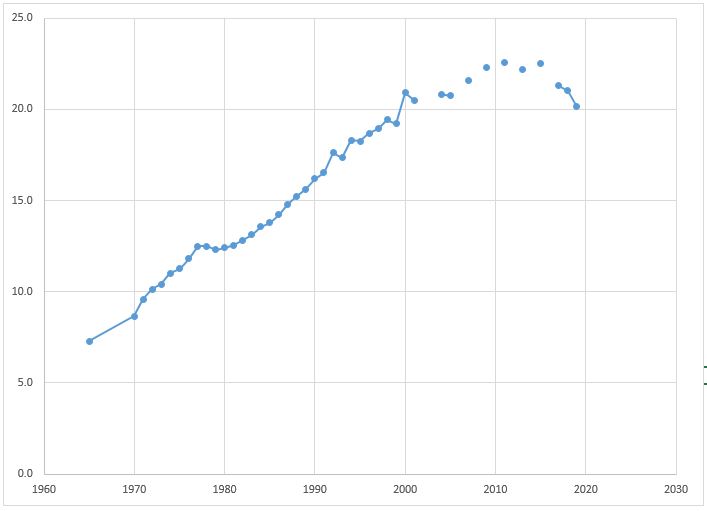

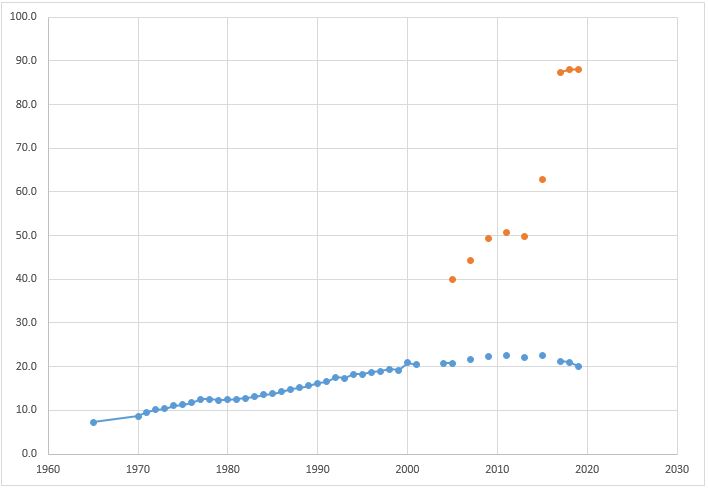

Discovery of North Sea gas in the 1960s resulted in the replacement of so called Town Gas from gas works such as that at Rotherhithe, by gas piped from below the North Sea. Although Rotherhithe has already closed in 1959, the majority of coal based gas works in the country had closed by the 1980s.

The lone gas holder at Rotherhithe now stands as an isolated reminder of this period of south London industrial history.

The gas holder stands next to the remains of another of the areas lost industries. This is the Surrey Basin, one of the few reminders of the large area of docks that once occupied this area of Rotherhithe. The towers of the Isle of Dogs are in the background.

The following photo is from Salter Road, a road that did not exist when the Rotherhithe gas works were in operation. The space in front of the camera, and the space occupied by the houses behind the trees was the space covered by the buildings of the gas works, which fed gas to the gas holders which are to the left of where I was standing to take the photo.

Crossing Salter Road and looking back at the gas holder, which now supports mobile phone antennae’s at the very top.

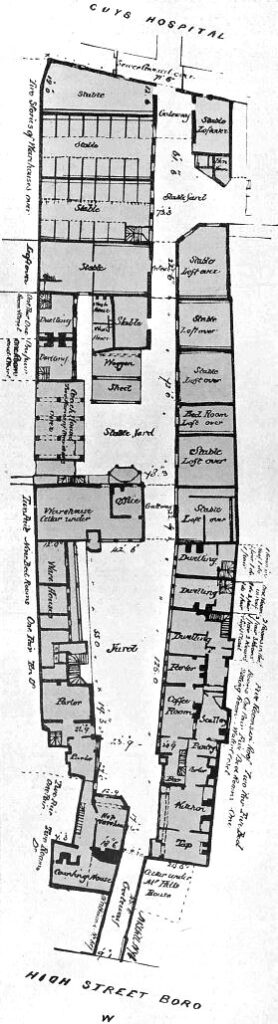

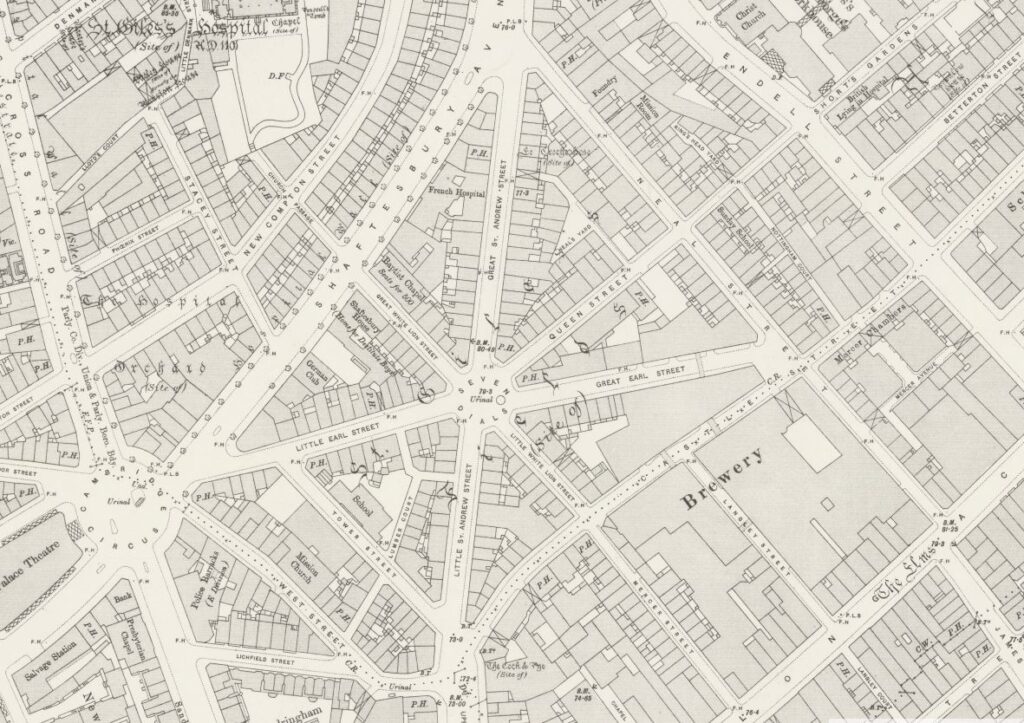

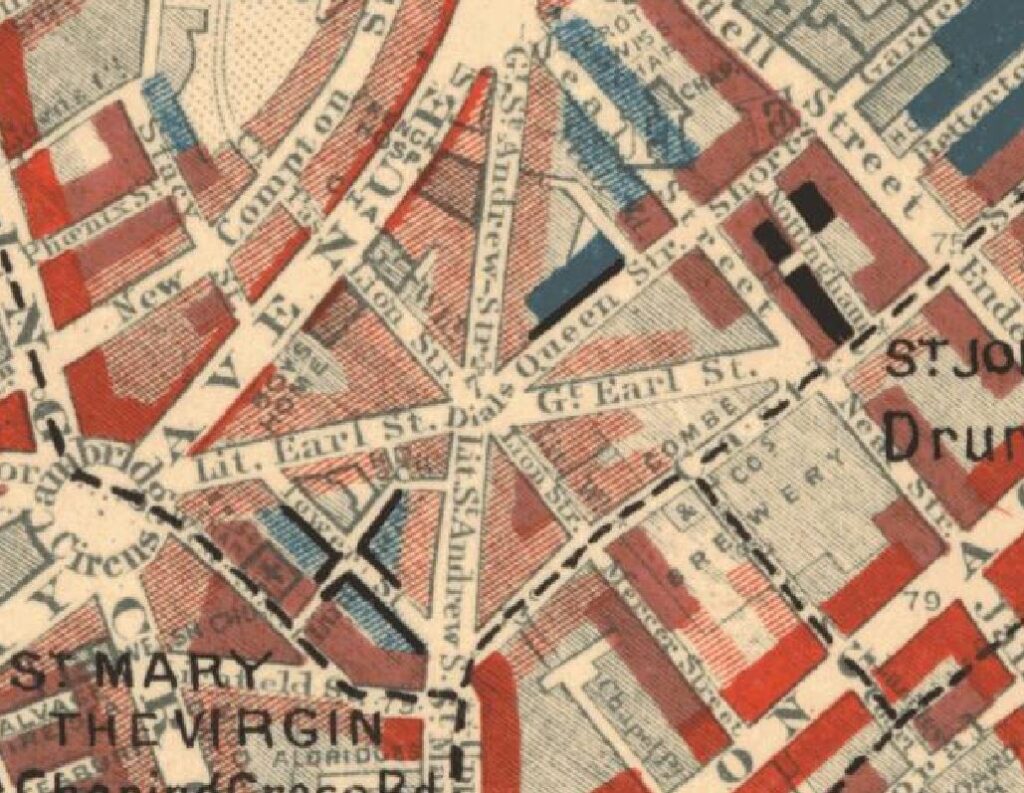

The following map from 1895 shows three gas holders with the main buildings of the Rotherhithe Gas Works to their north. There were a total of four gas holders over the life of the gas works (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

Of the three shown in the map above, one was destroyed by war time bombing. I suspect that this was the smaller holder between the two outer holders, as it is not shown in the 1950 map, or in my father’s photo. The larger of the two gasholders was demolished at the same time as the rest of Rotherhithe gas works in the 1960s and 70s, leaving only the holder that remains today.

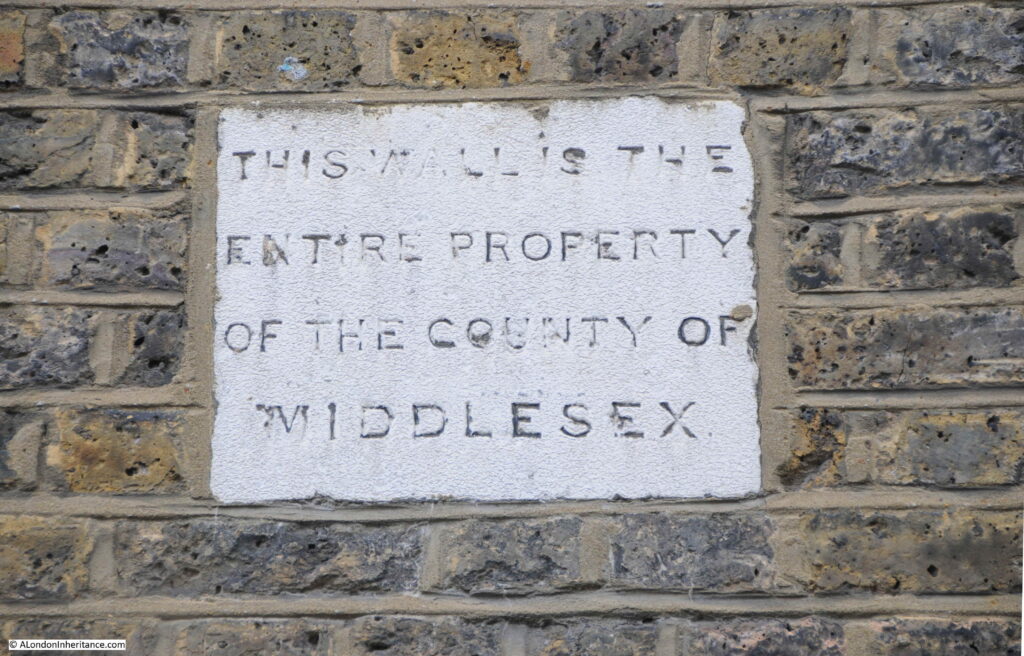

Apart from the gas holder, there is part of the site wall remaining alongside the Surrey Basin. Another part of the gas works infrastructure that we can see today is shown in the above map. If you look at the very top centre of the map there is a pier extending into the River Thames.

This was the pier used by ships bringing coal to the gas works, and looking at the map, you can see the conveyor system that carried coal from the pier, over Rotherhithe Street, to the retorts where the coal would be heated to produce gas.

The Rotherhithe Gas Works pier remains today. The view looking west:

Looking east along the river with the gas works pier, and the round air shaft building for the Rotherhithe Tunnel behind the pier on the right.

The Rotherhithe Tunnel was built under part of the site of the gas works, and during Parliamentary inquiries into the tunnel, the South Metropolitan Gas Company objected to the construction of the tunnel. Mr. George Livesey, chairman of the gas company stated in his evidence that “the proposed tunnel would pass under a corner of the works of the gas company where they had important buildings, retort houses, coalhouses, and so forth. These structures were of considerable weight, and the foundations were thoroughly sound. If there was any disturbance to the foundations – which were taken down to the gravel – it would put the retort house out of use, and if that happened in winter time it would be a very serious matter.

Pumping operations such as would have to be carried out by the County Council in constructing their tunnel might be a source of serious damage to the company’s works. The gas tanks were set into deep excavations full of water, and if this water and the sand in the foundations were interfered with the results would be that the tanks would leak”

it appears that the company had suffered damage to their operations on the Greenwich Peninsula when the Blackwall tunnel had been built, and they had not received any compensation for this damage, and they wanted a clause in the bill for the Rotherhithe tunnel to ensure they received compensation for any damage to the Rotherhithe works.

The statement about the gas tanks being set into deep excavations, full of water explains why the site today is a complex site to prepare for new building. The tank below ground of the existing gas holder is still in place, as is the tank of the demolished gas holder which was simply capped at the time. These tanks will need to be drained of polluted water and sludge and the hole refilled ready for building above.

I am not sure what the current state of the proposals for the site development are, I suspect that COVID has delayed the process.

Whilst there is an obvious need for more housing across London, it is a shame that another part of London’s industrial history will be disappearing.

This post has covered the history of the gas companies and the Rotherhithe gas works at a very superficial level, this is the problem with a weekly blog, I can only cover topics to a limited level.

The National Archives have a brief summary of the history of each gas company. Use the search box on their site to search for a company. The Early London Gas Industry site by Mary Mills is a fantastic resource covering the gas industry in London.

Although the area has changed significantly since 1948, I am pleased to have found the location of another of my father’s photos. Rotherhithe and Bermondsey is an area I will be returning to in the future.