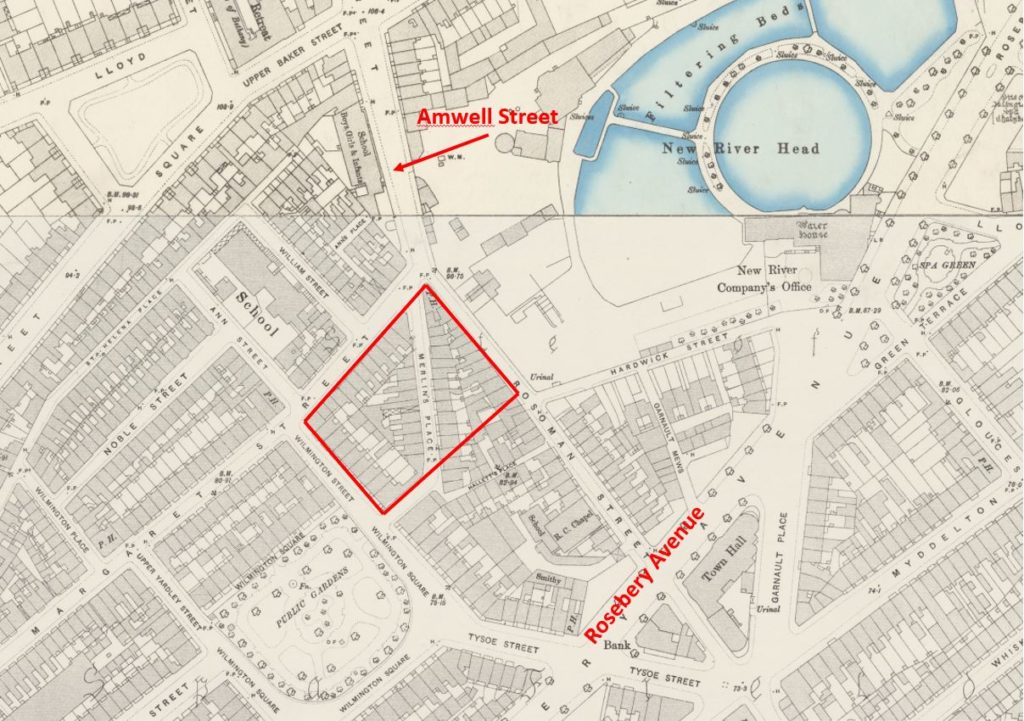

A couple of week’s ago I wrote about the New River Head. Whilst in the area, I took advantage of a walk along Rosebery Avenue, St John Street and Amwell Street to visit the location of some of our 1985 photos, and also to explore the area in a bit more detail. What follows is therefore a rather random walk, but as with any London street, there is so much interesting architecture, history and people to discover.

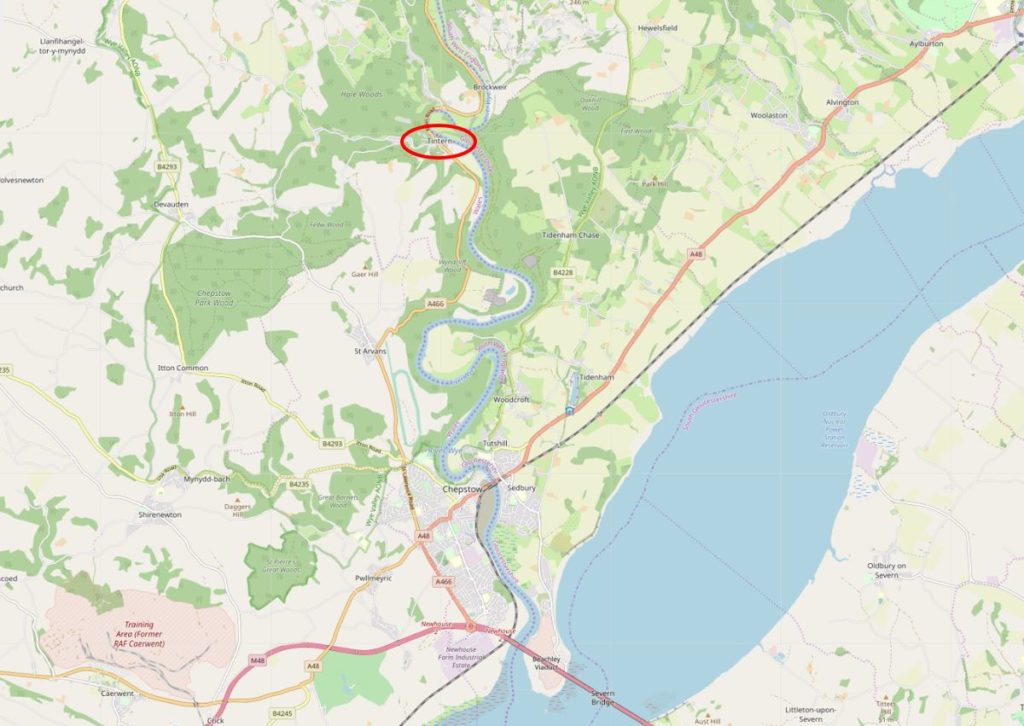

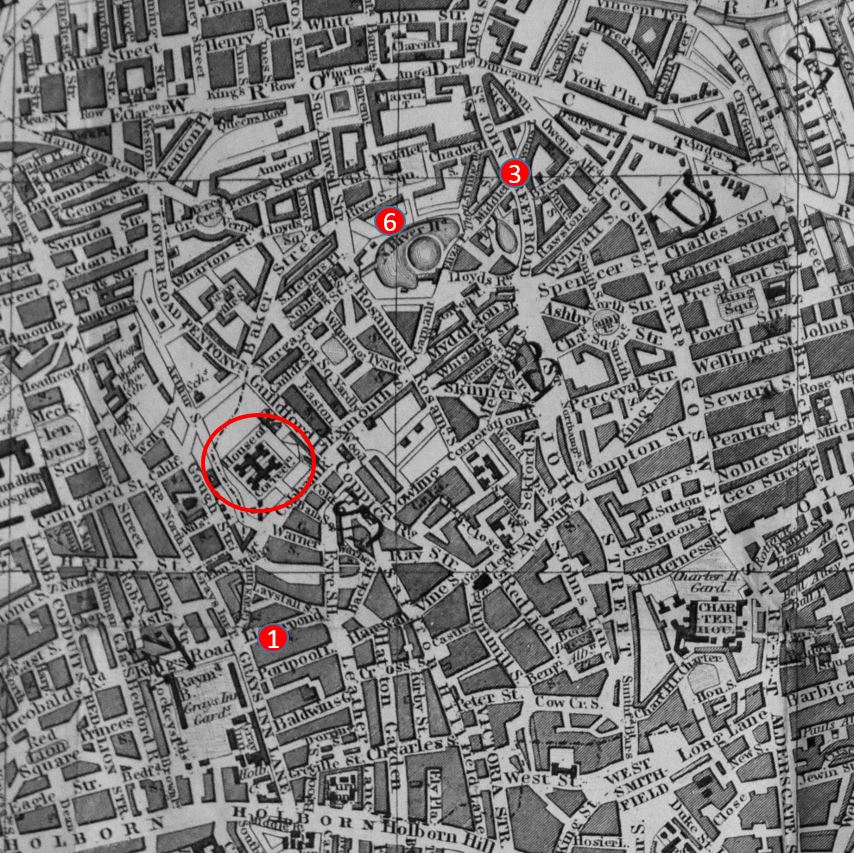

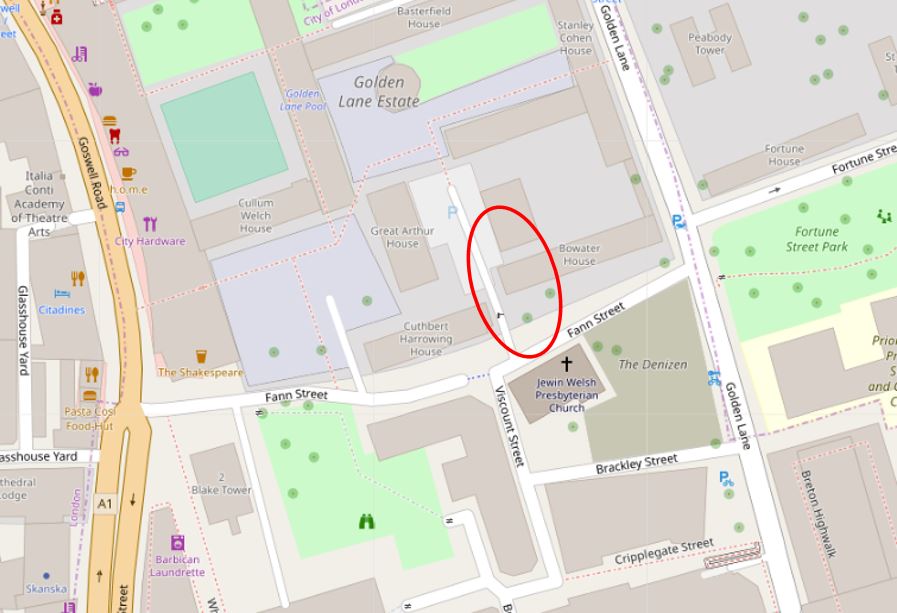

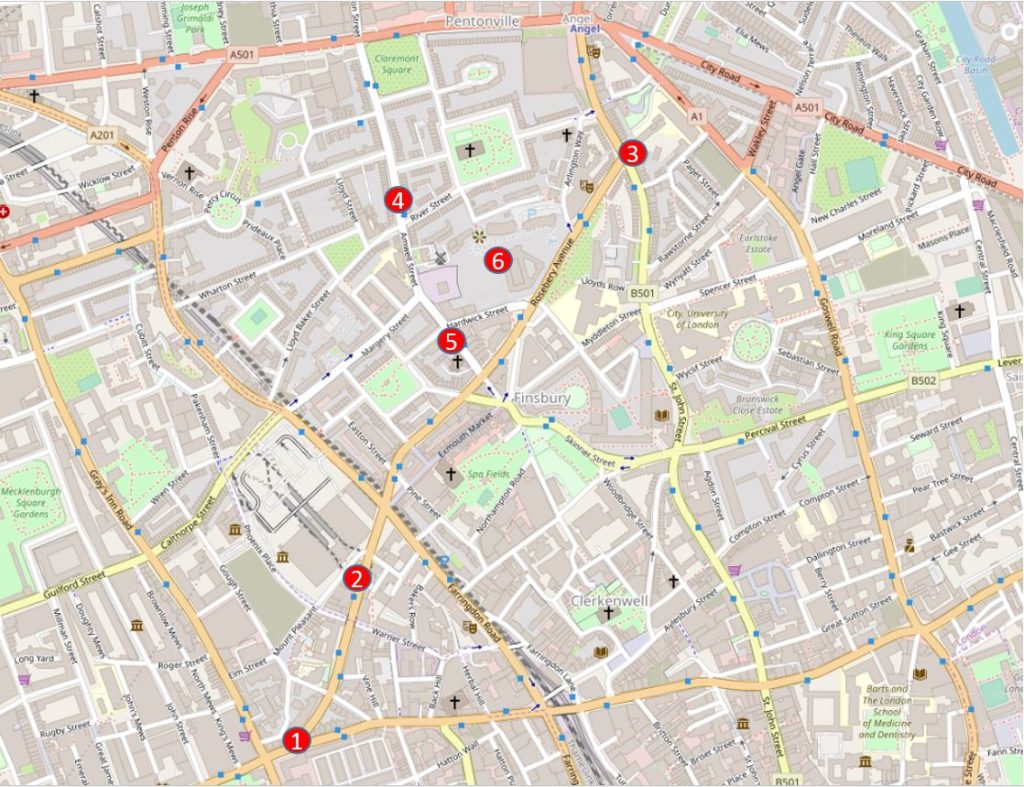

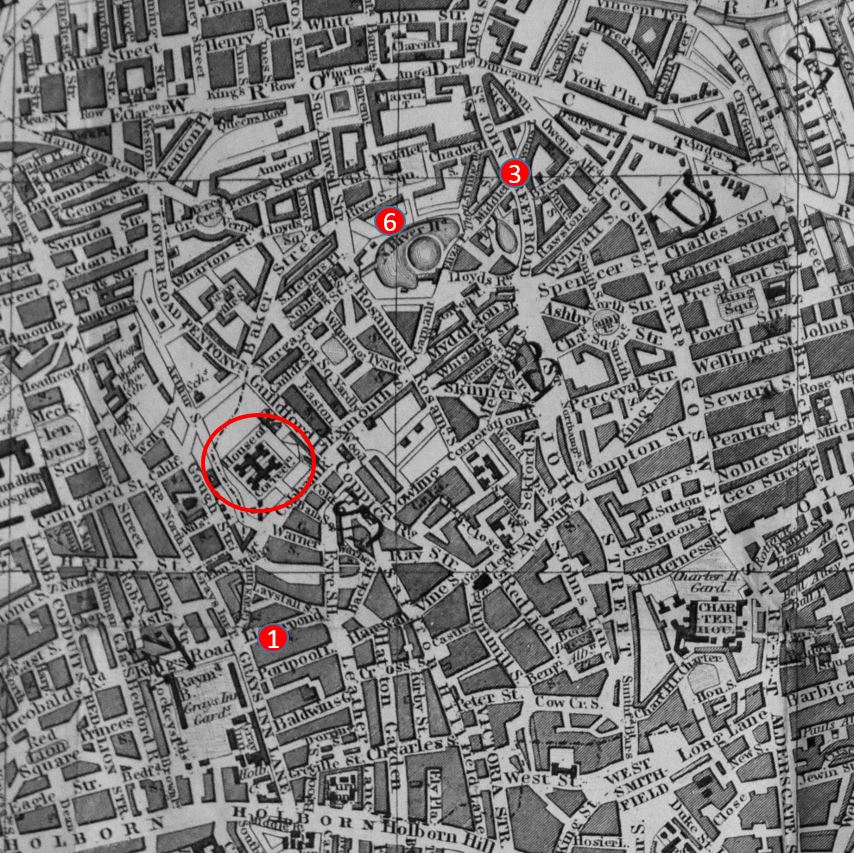

The following map shows some of the key locations in this week’s post (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

- Location 1 is the starting point, at the junction of Rosebery Avenue and Clerkenwell Road

- Location 2 is the site of a hairdressers photographed in 1985

- Location 3 is a row of 18th century houses which in 1985 looked doomed to demolition, and also where Rosebery Avenue meets St John Street

- Location 4 is a long open chemist in Amwell Street

- Location 5 is an old engineering business also in Amwell Street

- Location 6, for reference, is New River Head, the location of the post a couple of weeks ago.

Rosebery Avenue runs from points 1 to 3 on the map, and is one of those late Victorian streets, built to support the increasing volume of traffic across London, and to provide a wide through route where before only a maze of narrow streets existed.

Clearance of the route commenced in 1887, and the new street was opened in July 1892. The new street was named after Lord Rosebery, the first chairman of the London County Council. Lord Rosebery had resigned from the LCC a few days before the opening of Rosebery Avenue, so John Hutton, the vice chairman took on the task of formally opening the street.

Compared to many other 19th century London street openings, that of Rosebery Avenue seems to have been rather subdued. The Illustrated London News reported simply that:

“The new street from the Angel at Islington to the Holborn Townhall, Gray’s Inn Road, called Rosebery Avenue, was opened on Saturday, July 9, by the Deputy Chairman of the London County Council. It is 1173 yards long, straight and broad, with a subway under it for laying gas and water mains and electric wires. It has cost £353,000, but part of this expenditure will be recovered by the sale of land”.

As well as being the first chairman of the LCC, Lord Rosebery was a prominent politician of the late 19th century and was a Liberal Party Prime Minister between March 1894 and June 1895 after William Gladstone had retired. In 1895 Rosebery’s government lost a vote of confidence and the resulting general election returned a Unionist Government. He continued to lead the Liberal Party for a year, then permanently retired from politics.

Lord Rosebery after whom Rosebery Avenue is named:

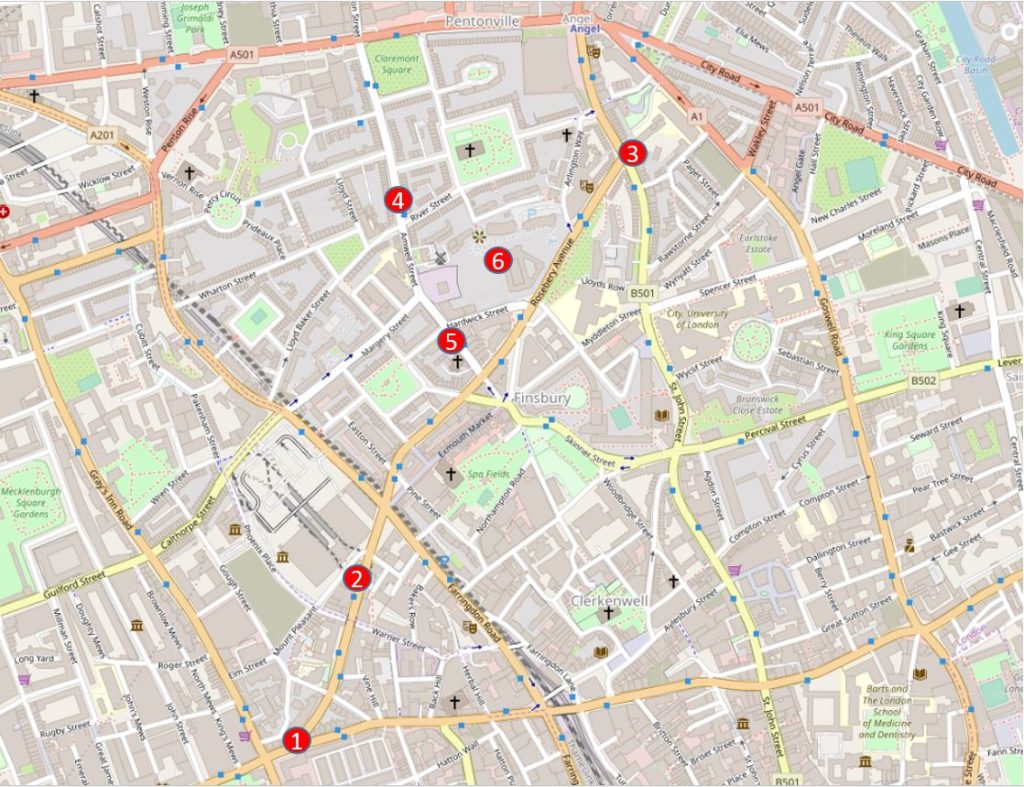

The following map extract is from “Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London; Showing The Grand Improvements for 1847”, and shows the area before the construction of Rosebery Avenue.

Location 1 is the same as in the above map, where the future Rosebery Avenue would meet Clerkenwell Road. Point 3 is where the new street will meet St John Street and point 6 is New River Head, with the ponds as they were in 1847.

The red oval is around a House of Correction. This was Coldbath Fields Prison, where the Mount Pleasant Post Office buildings would later be constructed. The south-east corner of these buildings are close to Rosebery Avenue.

Rosebery Avenue cut across the Fleet valley, cut through numerous streets, and cut short many streets including Exmouth Street which originally ran up to the site of the prison.

The following photo is at location 1, looking from Clerkenwell Road, across to the start of Rosebery Avenue:

Construction of Rosebery Avenue would displace a large number of people, as housing would be demolished to make way for the new street. The LCC mandated the construction of new housing to the south of the street before work commenced on the northern sections.

A short distance along Rosebery Avenue we can see the evidence of the LCC’s requirement with two identical blocks of flats lining the street – Rosebery Square, east and west. The following photo shows Rosebery Square east.

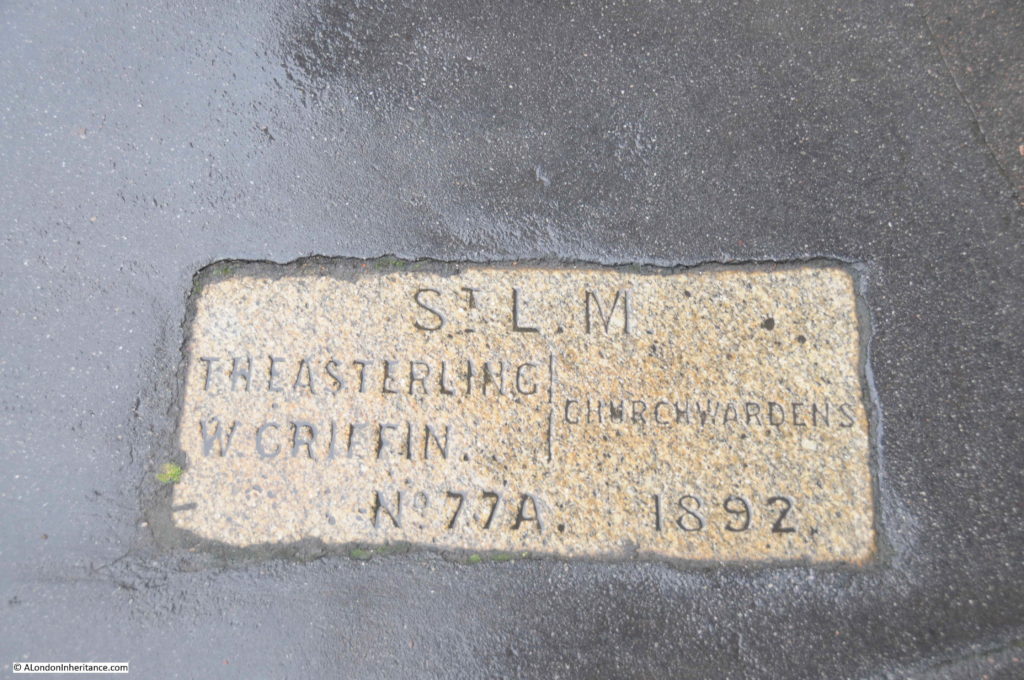

The new buildings were completed and ready to house those displaced by the new street in July 1891. A plaque on the wall records the names of the parish church wardens at the time of construction:

Parts of the southern section of Rosebery Avenue, between Laystall Street and Coldbath Square, are higher than the surrounding land. (See this post on Laystall Street) This allows extra lower floors to be part of buildings such as Rosebery Square, and also requires a viaduct as shown in the photo below where the street crosses Warner Street.

The photo above also shows how the buildings facing onto Rosebery Avenue drop down below the level of the street, and are therefore much larger than they appear.

A short distance further along, just before the junction with Mount Pleasant and Coldbath Square is the first of the locations photographed in 1985. In 2019, this is the Pleasant Barbers:

Who twenty-four years ago, were The Pleasant Gent’s Hairdresser, but at the same location:

It is interesting how the name of a trade changes over time. In the 1980s, to get your hair cut (for a man) you went to a Hairdresser. Today, you go to a Barber.

Hairdressers / Barbers are a type of shop we have been photographing for the past 40 years. They are usually local businesses, not part of a chain and have individual character. One of the few types of business that is not under threat from the Internet.

A few years ago I wrote a post about Hairdressers of 1980s London, featuring a selection from 1985 and 1986. Many have since disappeared, but there are still plenty to be found across London.

After the building with Pleasant Barbers, we find the south-east corner of the Royal Mail sorting office at Mount Pleasant.

The area occupied by the Mount Pleasant sorting office was the site of the House of Correction shown in the 1847 map – a location that deserves a dedicated article.

On the opposite side of Rosebery Avenue is the Grade II listed, former Clerkenwell Fire Station.

A fire station had existed on the site before the construction of the building we see from Rosebery Avenue. The site increased in importance over the years, becoming the Superintendent’s Station for the Central District by 1890.

The original fire station was extended over the years, and the section facing onto Rosebery Avenue was constructed between 1912 and 1917, and included parts of the original fire station buildings and the 1896 extensions to the building.

The architectural quality of the building draws from the London County Council’s development of London housing, as architects from the LCC housing department also had responsibility for fire station design from the start of the 20th century.

Clerkenwell Fire Station closed in 2014 – one of the ten London Fire Stations closed in the same year due to budget cuts when Boris Johnson was Mayor.

A reminder of the London County Council origins of Clerkenwell Fire Station:

The fire station stands at the south-eastern corner of the junction of Rosebery Avenue and Farringdon Road. This is where Exmouth Street was shortened slightly. In the photo below, I am looking across the junction to Exmouth Street.

If you look at the 1847 map, Exmouth Street was originally on a main route between Goswell Road and Gray’s Inn Road, along with Myddelton Street (a New River reference).

The construction of Rosebery Avenue faced a number of legal challenges and one of these was from the Marquis of Northampton who was after £22,000 of compensation due to the impact on his properties around Exmouth Street and that “the remainder of the estate would be seriously depreciated by the diversion of traffic from Exmouth Street to the new thoroughfare, thus converting that street into a back street”.

Exmouth Street today is a back street as far as traffic is concerned, but now is the location of the Exmouth Street market.

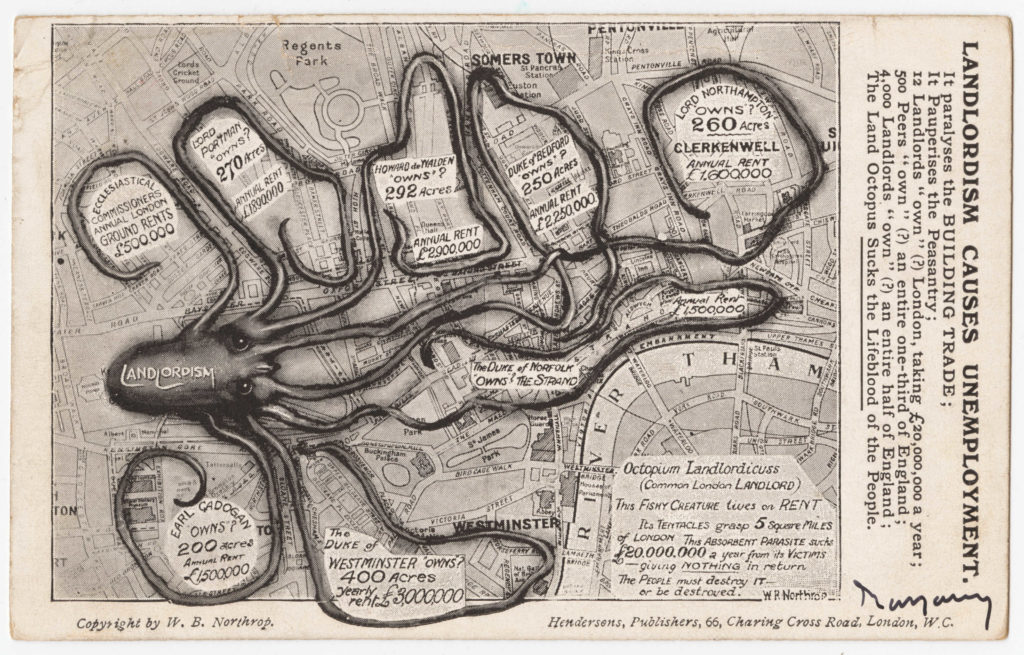

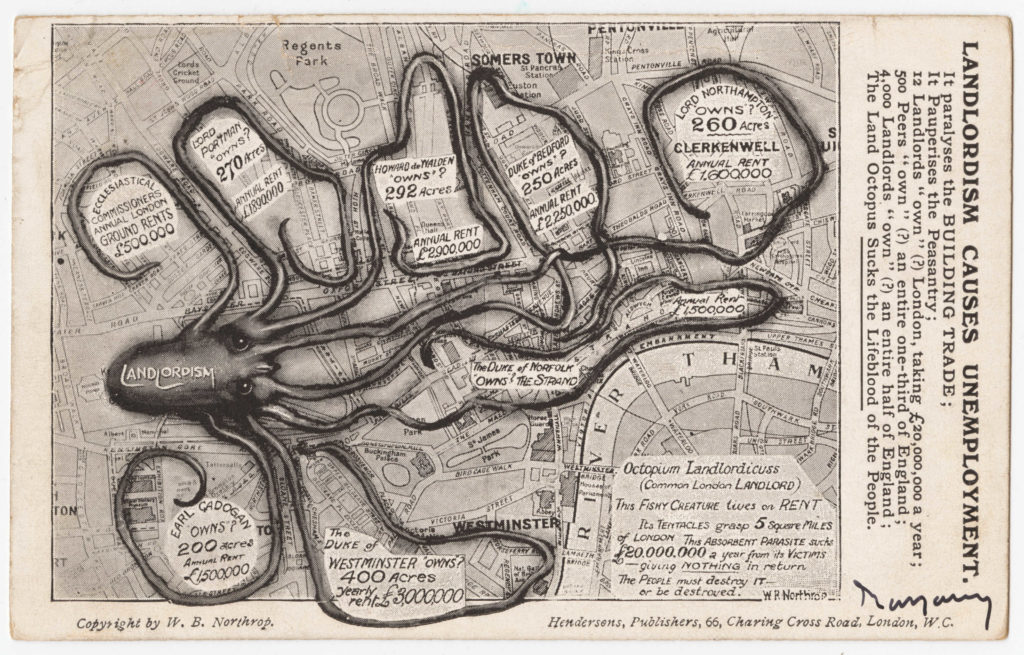

The Marquis of Northampton, or Lord Northampton and his landholdings in Clerkenwell featured in a map created in 1909 by William Bellinger Northrop and titled “Landlordism Causes Unemployment”.

Map from Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography and reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) Unported License

The aim of Northrop’s map was to show how “Landlordism” was strangling London, with large areas of the city being owned by the rich and powerful. Northrop claimed that Lord Northampton owned 260 acres in Clerkenwell and that this estate produced an annual rent of £1,600,000.

Continuing along Rosebery Avenue and the gradual increase in height is more apparent now, showing again why New River Head was located at close to the end of Rosebery Avenue as the drop to the city aided the flow of water from reservoir to consumer.

There are plenty of interesting buildings along the street, and a mix of architectural styles, one rather ornate building is the old Finsbury Town Hall:

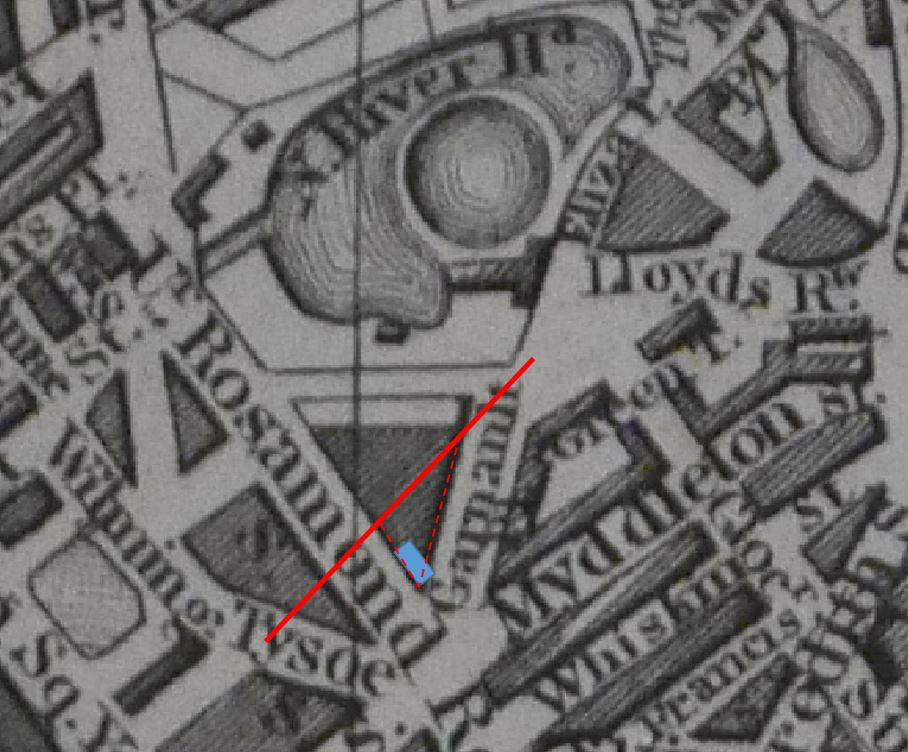

Finsbury Town Hall was built between 1894 and 1895 on land cleared following the construction of Rosebery Avenue. The original vestry building was in a southern corner of the same plot, however a much larger triangular plot of land had been reduced to a much smaller triangular plot as Rosebery Avenue cut through Rosamond Street (now Rosoman Street).

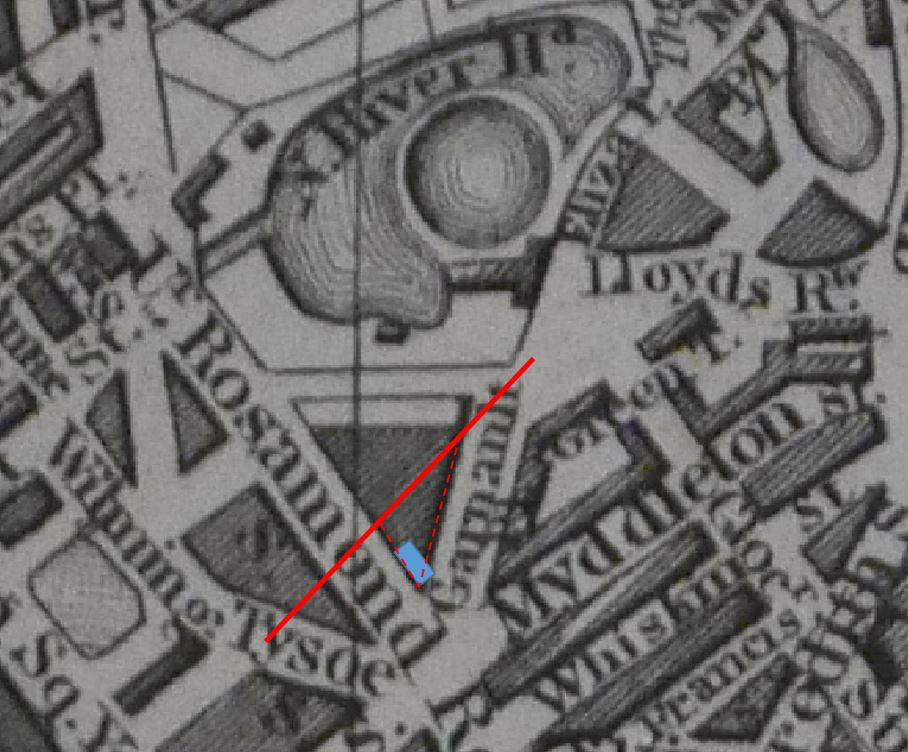

In the following extract from the 1847 map, the red line is the rough alignment of how Rosebery Avenue would cut through the area. The blue rectangle is the original vestry building, and the red dashed lines show the location of the Finsbury Town Hall which now faces onto Rosebery Avenue.

Soon after completion, in 1900, the building became the town hall of the new Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury.

As well as conducting council business for the borough, the town hall also had two large rooms available for council functions and public hire.

Typical of the events held in the town hall was a Carnival Ball of Costermongers belonging to the National Association of Street Traders held at Finsbury Town Hall on the 30th January 1928:

Local government changes meant that in 1965 the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury was integrated with the London Borough of Islington, and the majority of council functions moved to Islington Town Hall, with only a small number of council operations remaining in the old Finsbury building.

The building entered a gradual state of decay, and by the end of the 1980s, council functions had to be moved out of the building.

Finsbury Town Hall almost fell to the “luxury flat” fate of so many other buildings across the city, however in 2005 the dance school, the Urdang Academy commenced the redevelopment of the building, moving in, in 2006.

The building continues to be the home of the Urdang Academy, with some of the large halls still available for hire.

The ornate entrance to the old Finsbury Town Hall from Rosebery Avenue:

Leaving Finsbury Town Hall, we reach New River Head, which I explored a couple of weeks ago, and then Sadler’s Wells, which demands a dedicated post, so I will continue to the end of Rosebery Avenue, and to the junction with St John Street, where the next location of my 1985 photos is to be found.

Across St John Street, and just to the south of the junction with Rosebery Avenue is a short stub of street by the name of Owen’s Row, with a terrace of late 18th century houses. In 1985 these were boarded up, and appeared to be at risk:

Thankfully in 2019, they are still here and looking in good condition. A wider view in the photo below to the 1985 photo, showing Owen’s Row with the terrace, and the former Empress of Russia pub on the corner with St John Street.

The Empress of Russia pub dates to the early 19th century. The pub closed in 2000, went through a series of food related businesses, before returning to a pub in the form of the Pearl and Feather.

From 1985 the Empress of Russia was the regular London performance venue of the Ukelele Orchestra of Great Britain, where it was usual to hear the music of the Rolling Stones and the Velvet Underground played on the Ukelele.

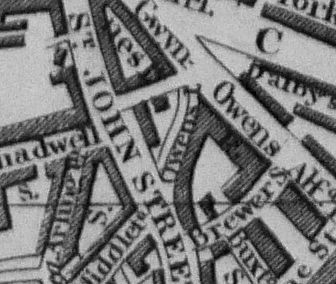

The alignment of Owen’s Row is down to the New River.

Building of a row of houses along the eastern bank of the New River commenced in 1773 by Thomas Rawstorne, who started building from the St John Street junction. When built, the houses faced onto the New River.

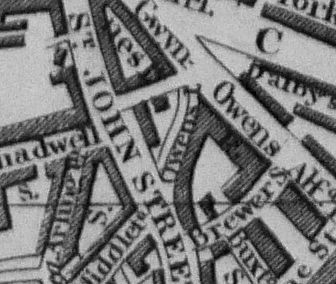

Look in the centre of the following extract from the 1847 map. Just above the S in the word Street of St John Street, is the word Owens, and to the left of this is the channel of the New River, flowing to the bottom of the map towards New River Head. In 1847 this section of the New River was still uncovered.

Owen’s Row would not become a street until 1862 when this section of the New River was enclosed and covered.

Today, the terrace consists of just four houses, but following the start of the street in 1773, houses extended further along the eastern edge of the New River. The following photo from 1946 shows the extended terrace, with a row of three floor buildings after those with four floors. These were later demolished, and the end of the original Owen’s Row is now occupied by the Sixth Form College of the City and Islington College.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_087_F3305

What is interesting in the above photos, is that in all photos of the remaining terrace, the bricks of the fourth floor are a very different shade to those on the lower three floors. It is more clearly visible in the 1946 photo, and would indicate that the terrace was originally built with three floors, with a later addition of a fourth floor.

Really good to see that part of the terrace remains, and that although boarded up in 1985, they were not demolished. Owen’s Row is also a physical reminder of the route of the new river, and when this terrace of houses looked out onto water flowing through the channel to New River Head.

Although I still had two 1985 photos to track down, I find wandering the streets fascinating, and in the streets around St John Street there are so many interesting places.

On the corner of St John Street and Chadwell Street are Turner & George, butchers.

The Turner & George business is new, only opening in the last few years, however the shop has long been a butchers.

In the tiling below the windows is the word BLAND. This refers to the Bland family who ran a butchers in St John Street from 19th century.

In 1882, there was a Mrs Sarah Bland recorded as Butcher of 563 St John Street-road, Clerkenwell, The present building is at number 399 St John Street, so Sarah Bland’s butchers may have been at a different location, or more likely, at the current corner location, which has changed number, as streets were frequently renumbered as streets changed over the years.

On the corner of Arlington Way and Chadwell Street is the business of Thomas B. Treacy – Funeral Directors.

I have not been able to find any evidence, however I suspect the building may have originally been a pub. The corner location, and the round corner for the building are typical of 19th century pubs.

One pub that does survive is The Harlequin in Arlington Way.

The Harlequin was first recorded as a beer house around 1848, with the current name being in use by 1894.

Although there is plenty of interest in the streets around Rosebery Avenue and St John Street, I had two more 1985 photo locations to find, so I walked across to Amwell Street to find the location of W.C. & K. King, Chemists, who had this wonderful lantern hanging outside the shop in 1985.

In 2019, the shop is still a chemists, and the same shop front survives, however the lantern has disappeared.

The lantern claims 1839 as the year the business was established, however I can find no evidence of when the business opened, or when W.C. & K, King where proprietors.

I continued walking down along Amwell Street, past the point where I photographed the base of the New River Head windmill, and then found this rather magnificent building – giving the appearance of a large brick built castle guarding Amwell Street:

This is the Grade II listed Charles Rowan House.

Built between 1928-1930 to provide accommodation for married police officers, the building was design by Gilbert Mackenzie Trench who was the architect for the Metropolitan Police.

Built of red brick, the large rectangular building provided 96 two and three-bedroom flats, arranged around a central courtyard. The longer sides of the building are along the roads leading off from Amwell Street, and it is in these two side streets that the arched entrances to the central courtyard and the flats can be found.

The building transferred to local council ownership in 1974. I am not sure how much of the building remains as council provided housing. I suspect many of the flats have transferred to private ownership through right to buy, and today, a 2 bedroom flat in Charles Rowan House can be had for £650,000.

The building is named after Sir Charles Rowan, the first Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and his obituary published on the 11th May 1852 in the London Daily News, reveals a link between the Metropolitan Police and the Battle of Waterloo:

“Death of Sir Charles Rowan K.C.B. – Sir Charles Rowan, later Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, died at his residence in Norfolk-street, Park-lane on Saturday the 8th inst. he entered the army as an ensign in the 52nd Light Infantry, in 1797, and served with that distinguished regiment in the expedition to Ferrol in 1800; in Sicily, in 1806-7; and with Sir John Moore’s expedition to Sweden in 1808. He joined the army in Portugal after the Battle of Vimiera, and served from that time with the reserve forces of Sir John Moore, and in the Battle of Corunna. he also served with great distinction both in Spain and Portugal, and commanded a wing of the 52nd at the Battle of Waterloo, when he was wounded; he was also wounded at Badajoz, on which occasion he received the brevet rank of lieutenant-colonel. In 1815 he was appointed companion of the Bath. From 1829, the year the Metropolitan Police Force was instituted, until 1859, he was chief commissioner, and for his services in that capacity was, in 1848, nominated a knight commander of the Bath”.

Fascinating that the building is named after someone who fought at the Battle of Waterloo, and that same person became the first chief commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

The construction of Charles Rowan House obliterated a street and a large number of houses, and it was here that Amwell Street ended.

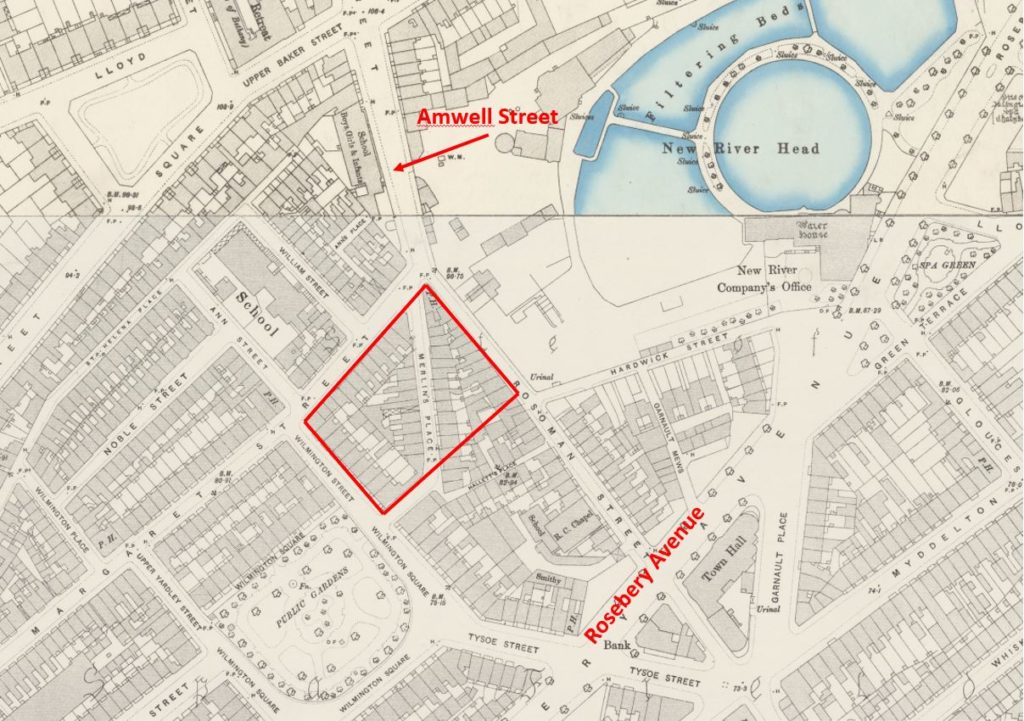

In the following extract from the 1896 edition of the Ordnance Survey map, I have marked the location of Charles Rowan House with the large red rectangle.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

Amwell Street ran to the northern tip of what would later become Charles Rowan House, and from then down to Rosebery Avenue, the street was named Rosoman Street. Today, Amwell Street extends onto Rosebery Avenue, replacing the Rosoman Street name.

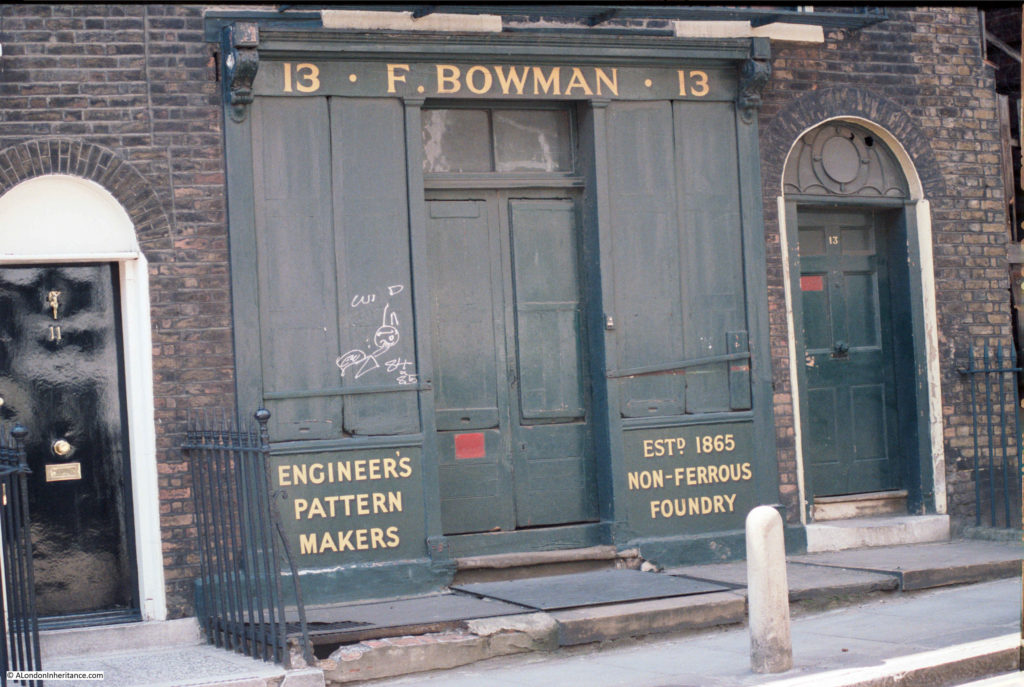

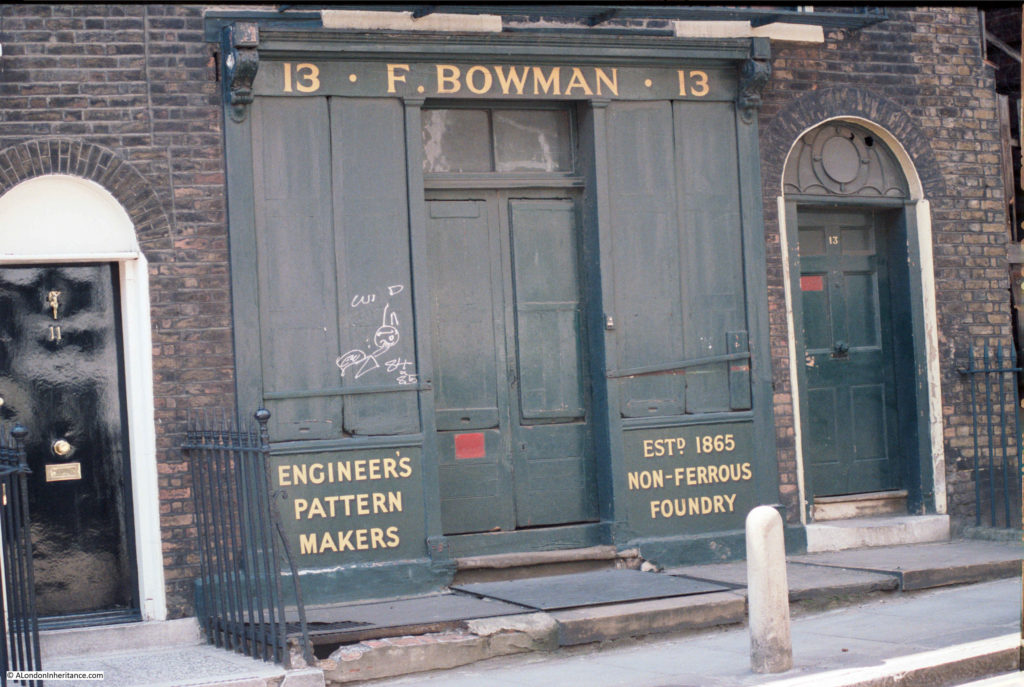

This is relevant as it helped me find more details of the following location, photographed in 1985:

In the 1901 census, the address was 95 Rosoman Street rather than 13 Amwell Street.

The building was occupied by:

- Frederick Bowman, aged 52 and occupation Brass Founder

- Ellen Bowman, aged 39, his wife

- Irene Bowman, aged 14, daughter

- Ruby Bowman, aged 13, daughter

- Theophilus Bowman, aged 11, son

- Christie Bowman, aged 7, daughter

- Helen Munto, aged 32, servant

If the business was founded in 1865 as recorded on the front of the building, then I am not sure it was the Frederick Bowman of the 1901 census, as he would have been too young, and all his children were recorded as being born in Chingford, Essex.

I cannot find any reference to an earlier F. Bowman. In the 1911 census, Frederick Bowman was still living at 95 Rosoman Street, aged 64 and still working as a Brass and Aluminium Founder. All his children still lived at home, however Helen Munto had left (perhaps returning to her native Scotland), and the new servant was Edward Redgrave, aged 30.

Frederick seems to have been a name used by the family over the generations, as Theophilus middle name was Frederick. Chingford also seems to have been a family connection as Theophilus would marry Florence May Jerome at Chingford in 1922.

Theophilus would go on to live in Chingford, but he would also carry on the family trade, as in the 1939 census, his occupation is given as Brass Moulder – what is not clear is whether he worked in Chingford, or commuted to the Rosoman / Amwell Street business.

The same location in 2019:

The 1985 photo implies that the entrance to the business was in the centre, with the entrance to the family home to the right.

In 2019 it looks as if the building has been converted to a home, with a single entrance door to the right, and the paving leading to the business door removed to open up the cellar.

Frederick Bowman’s name still looks onto Amwell Street.

A short distance on, and I was back on Rosebery Avenue. Although the walk did not have a theme, to me it is the fascination of what can be found on random walking across London, on this walk using some 1985 photos as a guide.

Businesses that continue to (hopefully) thrive on London’s streets such as the Pleasant Barbers, Lord Northampton’s hold over the land of Clerkenwell, a row of houses that owe their alignment to the New River, a block of flats named after a Waterloo survivor, and a street named after the first chairman of the London County Council, and future Prime Minister are typical of the fascinating stories to be found all over London.

alondoninheritance.com