Last week I had the opportunity to research the New River, and to walk around the site of New River Head, where the New River terminated, just south of the Pentonville Road.

The New River dates to the start of the 17th century, a time when there was a desperate need for supplies of clean water to a rapidly expanding city. Numerous schemes were being proposed, and the build of the New River tells the story of how the City of London, Parliament, the Crown and private enterprise all tried to gain an advantage and ownership of significant new infrastructural services, the power they would have over the city, and the expected profits.

The New River proposal was for a man-made channel, bringing water in from springs around Ware in Hertfordshire (Amwell and Chadwell springs) to the city. A location was needed outside the city where water from the New River could be stored, treated and then distributed to consumers across the city.

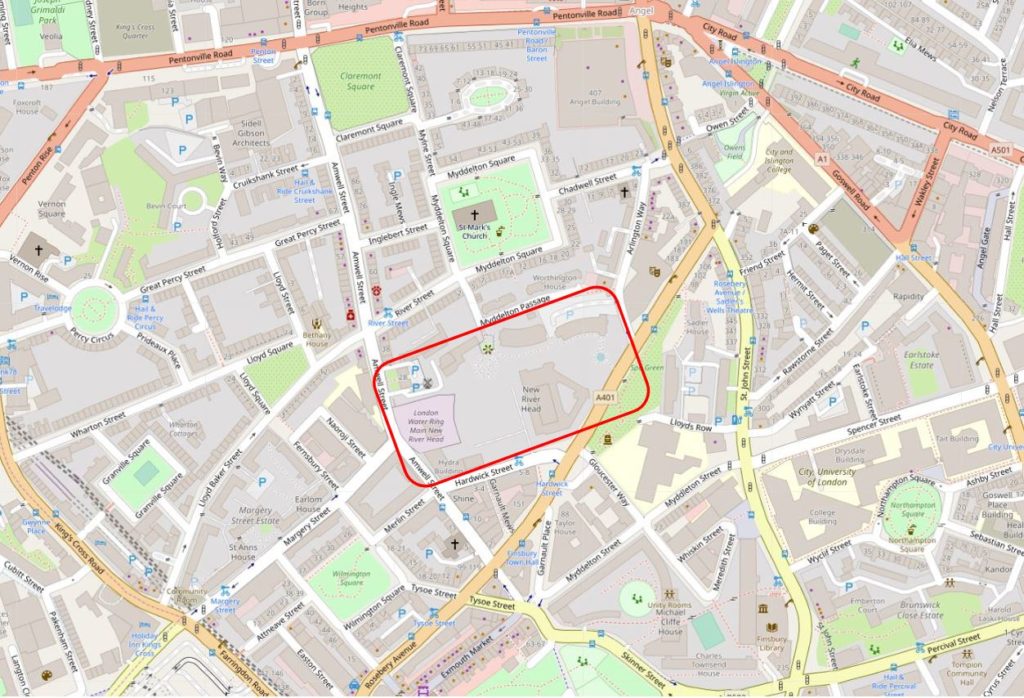

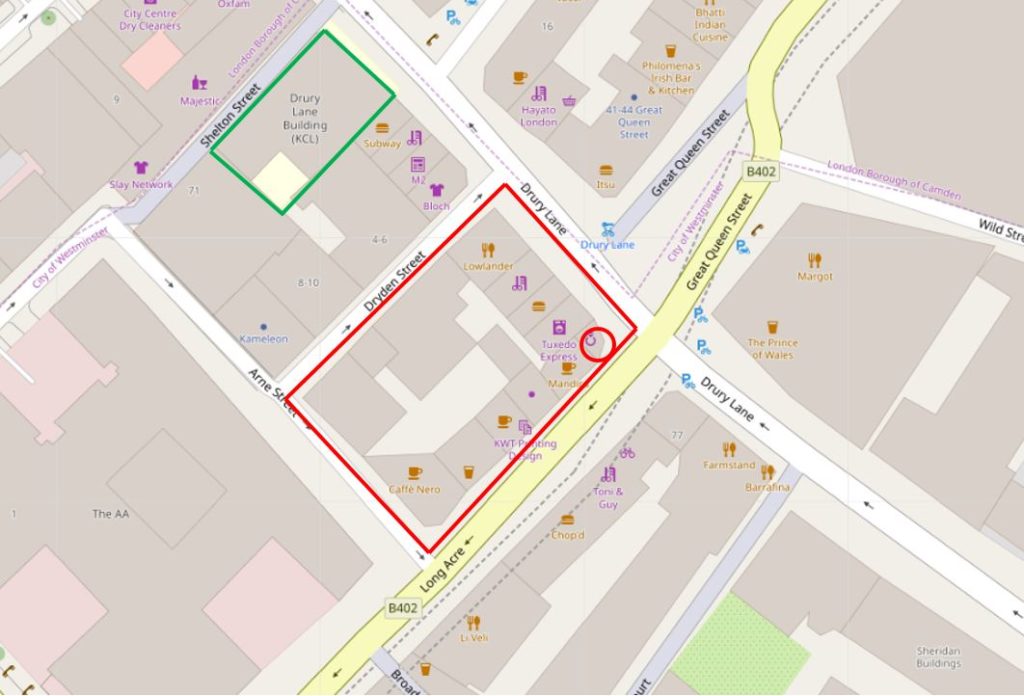

The site chosen, called New River Head, was located between what is now Rosebery Avenue and Amwell Street. The red rectangle on the following map shows the area occupied by New River Head (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The story of the New River dates back to 1602 when a former army officer from Bath, Edmund Colthurst who had served in Ireland, proposed a scheme to bring in water from Hertfordshire springs to a site to the north of the city.

As a reward for his military service, he was granted letters patent from King James I, to construct a channel, six feet wide, to bring water from Hertfordshire to the city.

Colthurst’s was not the only scheme for supplying water to the city. There were a number of other private companies, and the City of London Corporation was looking at similar schemes to bring in water from the River Lea and Hertfordshire springs.

Whilst Colthurst’s project was underway, the City of London petitioned parliament, requesting that the City be granted the rights to the water sources and for the construction of a channel to bring the water to the city.

In 1606 the City of London was successful when parliament granted the City access rights to the Hertfordshire water, a decision which effectively destroyed Colthurst’s scheme, which collapsed after the construction of 3 miles of the river channel.

It was an interesting situation, as Colthurst had the support of the King, through the letters patent he had been granted, whilst the City of London had the support of parliament.

The City of London took a few years deciding what to do with the water rights granted by parliament, and in 1609 granted these rights to a wealthy City Goldsmith, Hugh Myddelton. He was a member of the Goldsmiths Company, an MP (for Denbigh in Wales), and one of his brothers, Thomas Myddelton was a City alderman and would later become Lord Mayor of the City of London, so Myddelton probably had all the right connections, which Colthurst lacked.

Colthurst obviously could see how he had been outflanked by the City, so agreed to join the new scheme, and was granted shares in the project. Colthurst joining the City of London’s scheme thereby uniting the rights granted by James I and parliament.

Work commenced on the New River in 1609, but swiftly ran into problems with owners of land through which the New River would pass, objecting to the work, and the loss of land. A number of land owners petitioned Parliament to repeal the original acts which had granted the rights to the City, however when James I dissolved Parliament in 1611, the scheme was given three years to complete construction and find a way to overcome land owners objections, as parliament would not be recalled until 1614.

There were originally 36 shares in the New River Company. Myddleton had decided to enlist the support of James I to address the land owners objections, and created an additional 36 new shares and granted these to James I who would effectively own half the company.

in return, James I granted the New River Company the right to build on his land, he covered half the costs, and Royal support influenced the other land owners along the route, removing their objections, as any further attempts to hinder the work would result in the king’s “high displeasure”.

The New River was completed in 1613. It was a significant engineering achievement. Although the straight line distance between the springs around Ware and New River Head was around 20 miles, the actual route was just over 40 miles, as the route followed the 100 foot height contour to provide a smooth flow of water, resulting in only an 18 foot drop from source to end.

The New River Head location was chosen for a number of reasons. A location north of the city was needed to act as a holding location, from where multiple streams of water could then be distributed through pipes across the wider city.

The location sat on London Clay, rather than the free draining gravel found further south in Clerkenwell, and it was also a high point, with roughly a 31 meter drop down to the River Thames, thereby allowing gravity to transport water down towards consumers in the city.

The site already had a number of ponds, confirming the suitability of the land to hold water.

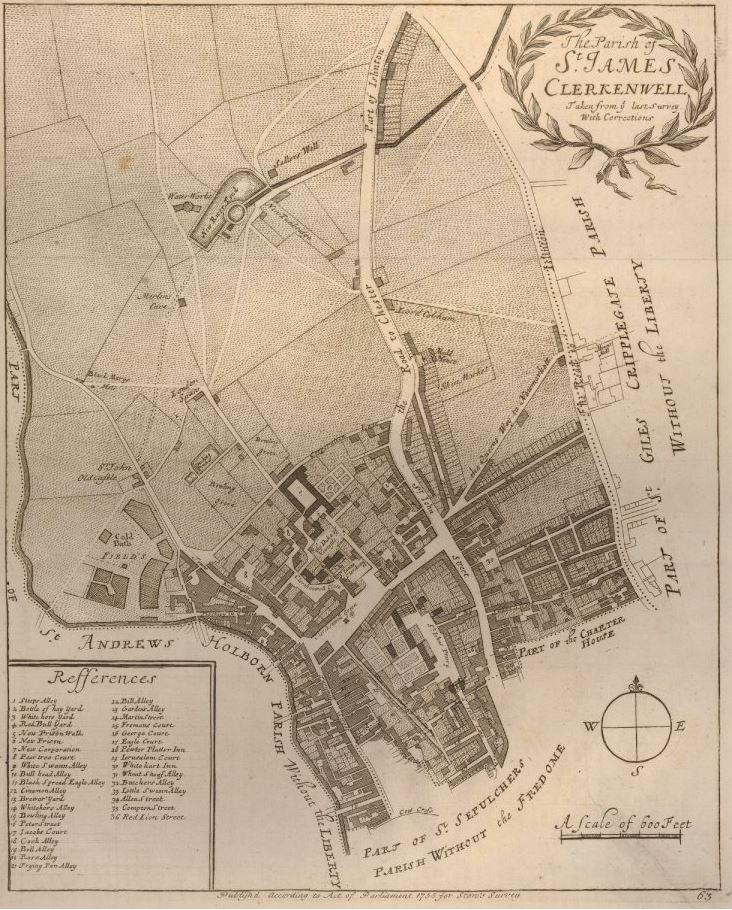

The following map from Stow’s Survey of London, dated around 1720, shows the location of New River Head, still in fields to the north of the city, with the New River feeding in from the right.

The New River project was a success, however by the end of the 17th century, the New River Company was supplying water to a considerable part of London, and had reached the organisational and technological limits of the time.

Whilst there were no significant problems with transporting water from Hertfordshire to New River Head, the real problems were distributing water onward across the city, where a system of pipes had grown over the years without any integrated planning, and no real understanding of the implications of water pressure, pipe size, height profiles etc.

Users were starting to complain, water could be cut off for days, pressure was frequently low, and the number of consumers continued to grow rapidly, for example in the ten years between 1695 and 1705 an additional 600 new consumers had been added in the West End, an area of considerable growth for the New River Company.

The West End also had unique problems as it was higher than the City and the difference in height required different distribution methods, rather than just adding more pipes to an already overstretched network.

Sir Christopher Wren was asked to help with understanding the problems of distributing water to Soho Square in the West End, however Wren looked at the whole system and recommended that the problems could only be addressed by effectively replacing the entire system with a new, integrated design.

The New River Company also commissioned John Lowthorp (a clergyman, who was also a member of the Royal Society) to look at the distribution problems,

Lowthorpe established that it was not water supply problems to New River Head (indeed the New River supplied enough water for the whole of London), as with Wren, Lowthorpe identified the distribution network and the organisation of the company.

The New River Company undertook a significant reform of their operations over the course of the 18th century. An integrated approach to distributing water, placement of valves and cisterns, use of different pipe bores and careful surveys of the height profile of the distribution network, and the locations of consumers.

The New River Head location also expanded with additional holding ponds, and in 1709 a new reservoir called the New or Upper Pond was constructed, a short distance north from New River Head, where Claremont Square stands today towards Pentonville Road.

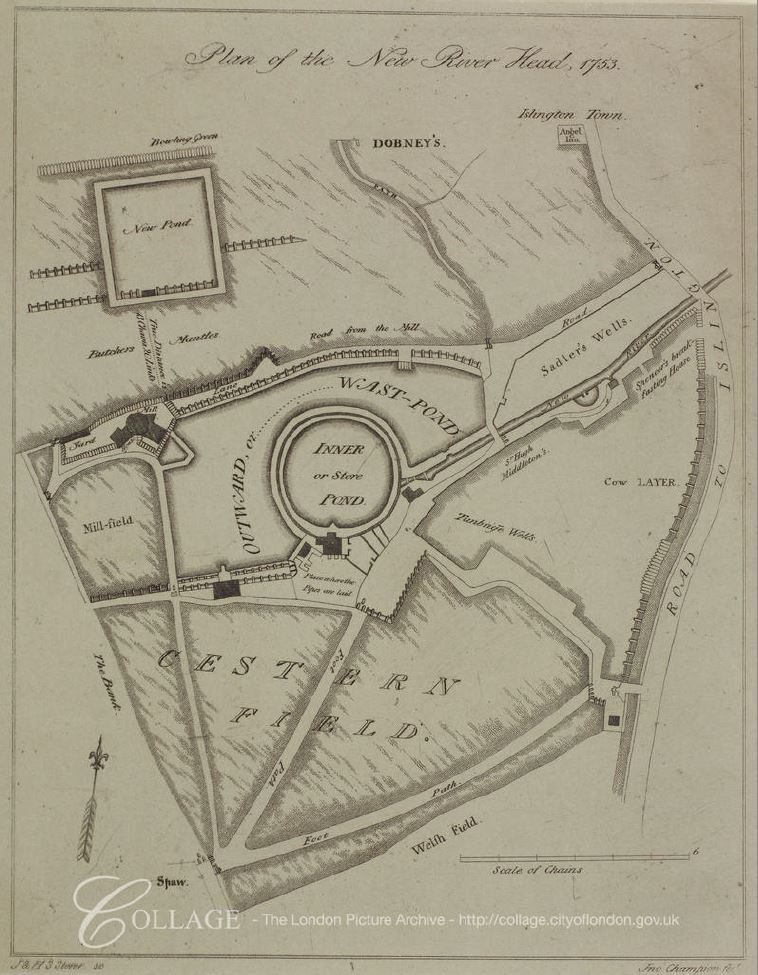

The following plan shows the New River Head in 1753. The original Inner pond, built for the 1613 opening of the New River, surrounded by later ponds, and to the upper left, the New Pond dating from 1709.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5440560

The New Pond was higher than the main New River Head site, so a means of pumping water was required and initially a windmill was constructed at the New River Head site to pump water up to the New Pond, however this was an inefficient method. Water could not be pumped at times of insufficient wind and the windmill was also damaged during times of high wind. The windmill was soon replaced by horsepower, and then by steam pumps in a new pump and engine house.

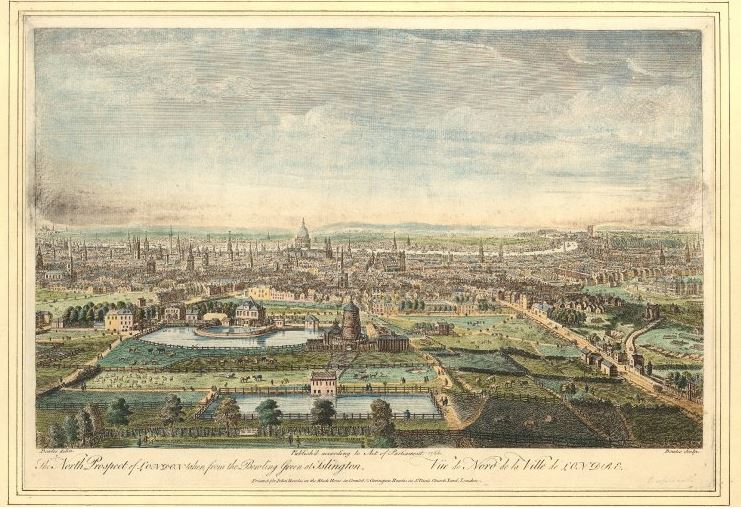

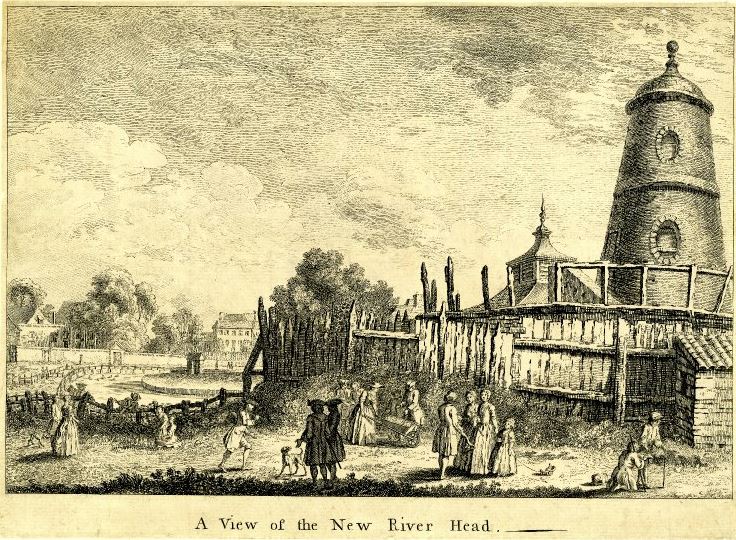

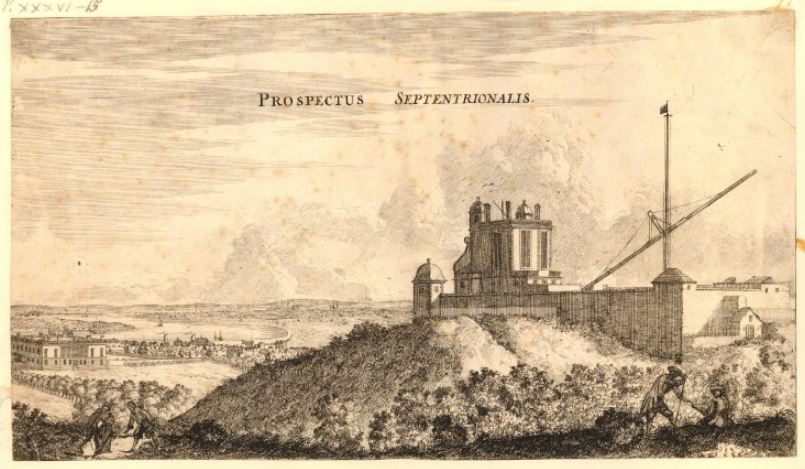

The following print shows New River Head in 1752.

The New Pond is at the bottom of the picture, the ponds at New River Head are just above and the windmill can be seen to the right of the New River Head ponds. This print also shows how the buildings of the city are gradually creeping towards New River Head, when compared to the map from 1720 – all new consumers for the New River Company.

This print from the 1740s shows New River Head and the windmill.

The growing demand for water also meant that the capacity of the original Hertfordshire springs was insufficient. The New River Company had started to use the River Lea as an additional source of water and in the 17th century had constructed pipes to take water from the River Lea to the New River.

Bargeman and Mill owners along the River Lea were not happy with the impact of the New River on the volume of water and rate of flow along the River Lea, resulting in a number of disputes.

Parliament provided their approval to an agreement drawn up between the trustees of the River Lea Navigation and the New River Company in 1739, which allowed the New River Company to continue drawing water on payment of £350 per annum to the River Lea Navigation.

There is so much history to New River Head, however this post is already far too long, so a brief look at a couple of maps to show how the site then developed to the site we see today.

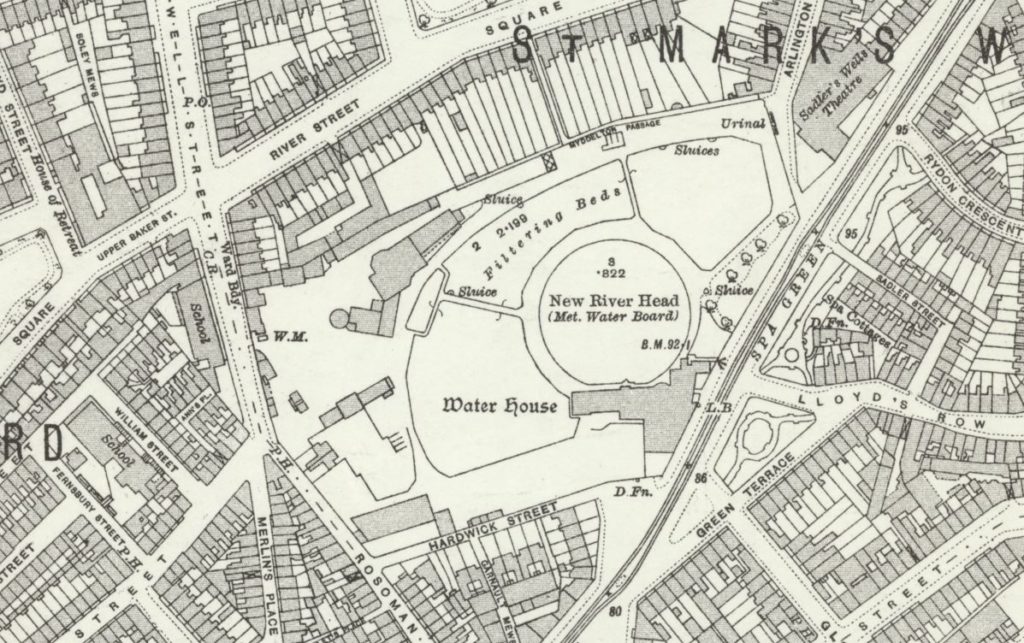

This 1913 revision of the Ordnance Survey map, shows New River Head, with the central round pond, and surrounding filter beds. The map also shows the level of development during the 19th century with the fields that surrounded the site in the 17th century, now covered with housing and streets.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

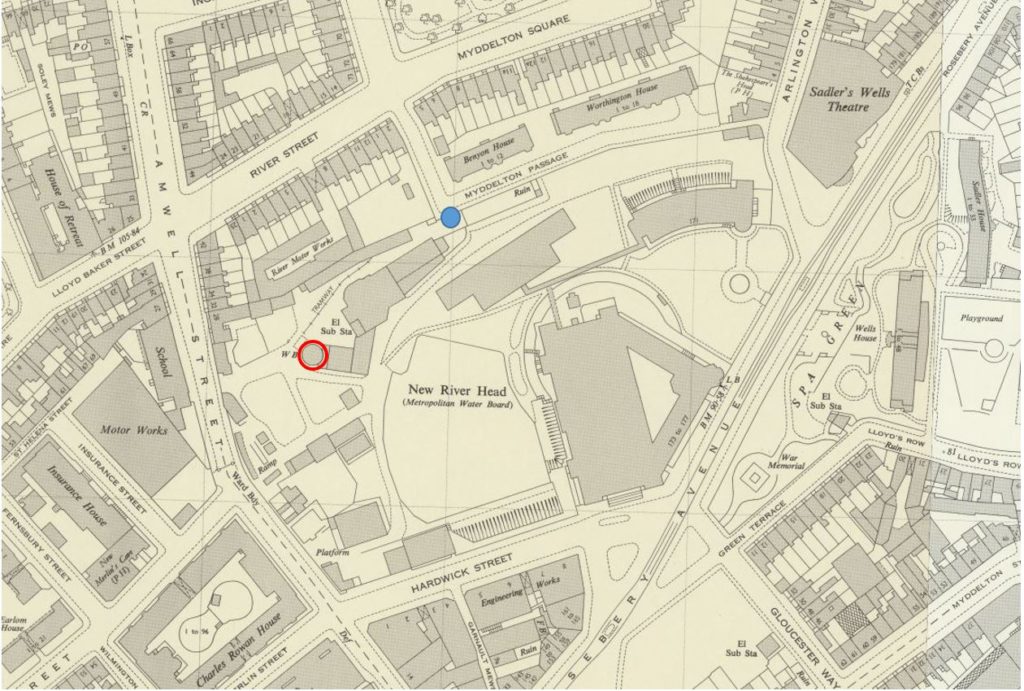

Fast forward to the 1952 revision, and we can see the large head office of the Metropolitan Water Board (discussed further down the post) dominates the site, and covers much of the original location of the round pond, with only parts of the northern edge remaining (which we can still see today).

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

In the map, I have marked the location of the New River Head viewing point (see further down the post) by a blue circle, and the red circle outlines the base of the original windmill used to pump water to the Claremont Street reservoir.

The following photo from Britain from Above, dated 1952, shows the New River Head location. It is really only with an aerial view that you can appreciate the head office of the Metropolitan Water Board in the centre of the photo.

Time for a walk around the site today, to see what is left of New River Head.

As part of the New River Path, developed to follow the route of the New River between Hertford and Islington, Thames Water created a viewing platform to look over the site of New River Head. To get to there, i walked up Rosebery Avenue, and just before the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, turned left into Arlington Way, then just before the Shakespeare’s Head pub, turned left into Myddleton Passage.

At the point where Myddleton Passage does a 90 degree bend up to Myddleton Square (both named after Hugh Myddleton), there are two metal gates, the one on the right provides access to the viewing platform.

There are a number of information panels lining the fence providing some background to the New River and New River Head.

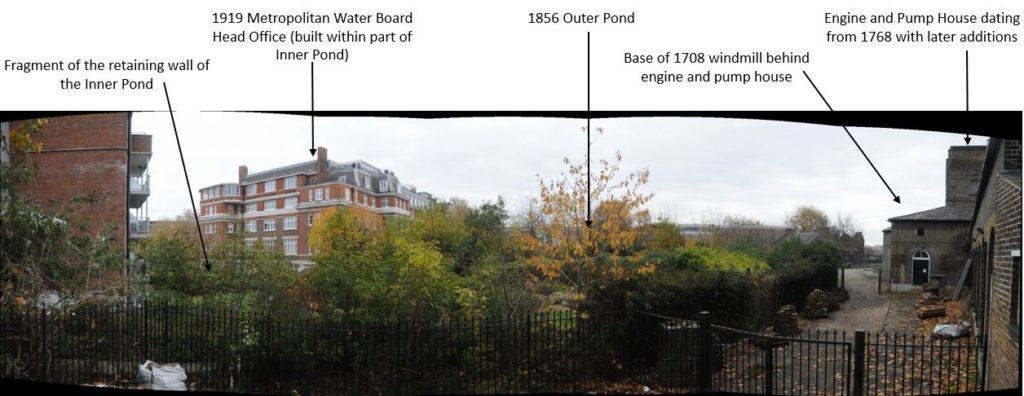

The concept of having a viewing platform at the end of the New River Path, overlooking the place where water emptied out into the ponds and the infrastructure to distribute the water onward across London is brilliant, however I must admit I was somewhat disappointed by the limited view. Much of the original history of the site is either obscured by plant growth, or buildings, or is just too low to be visible.

The following panorama shows the view from the viewing platform, and I have marked some of the key features which are either visible, or hidden.

Fortunately, taking a walk around the wider area reveals much more of New River Head and the New River Company, so here is a tour round the site starting with the magnificent Head Office of the Metropolitan Water Board constructed in 1919 / 1920. This is the view of the building as you walk up Rosebery Avenue from the south.

It is hard to appreciate the full size, or shape of the building from ground level. The Britain from Above photo shown earlier in the post shows what a magnificent building this is when the full building can be appreciated.

There are multiple reminders of the original function of the building and New River Head, to be found all over the building:

Walking further north along Rosebery Avenue, and this is the view looking back towards the Metropolitan Water Board head office. The full area on the right is part of the original New River Head.

In the above photo, where the head office building ends along Rosebery Avenue, there are gates which provide a glimpse of the original round pond. The photo below shows part of the retaining wall of the round pond behind the far fence – later upgrades and restorations so not exactly the 1613 walls, but retaining the position of the original round pond.

To the north of the site is the magnificent Grade II listed, 1938 Laboratory Building, designed by John Murray Easton and formerly the water testing centre for Thames Water.

The Laboratory Building is now home to 35 apartments. On the rounded corner of the Laboratory Building is the seal of the New River Company:

The seal depicts the hand of Providence bestowing rain upon the city. The motto “et plui super unam civitatem” translates as “and I rained upon one city”.

This is the turn off from Rosebery Avenue to get to Myddleton Passage:

The view along Myddleton Passage. The passage can be seen along the northern boundary of New River Head in the maps above. The wall on the left is the boundary wall from 1806-7.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries this passage, alongside the water works was a dark and isolated place at night, and a number of crimes were reported in the press of the day. For example from the London Daily News on the 26th March 1846 “Robbery from the person of Mr Thomas Woods, of Number 9 Wardrobe-place, Doctors Commons whilst passing through Myddleton-passage, Clerkenwell, a striped silk purse, containing twenty sovereigns and twenty shillings in silver”.

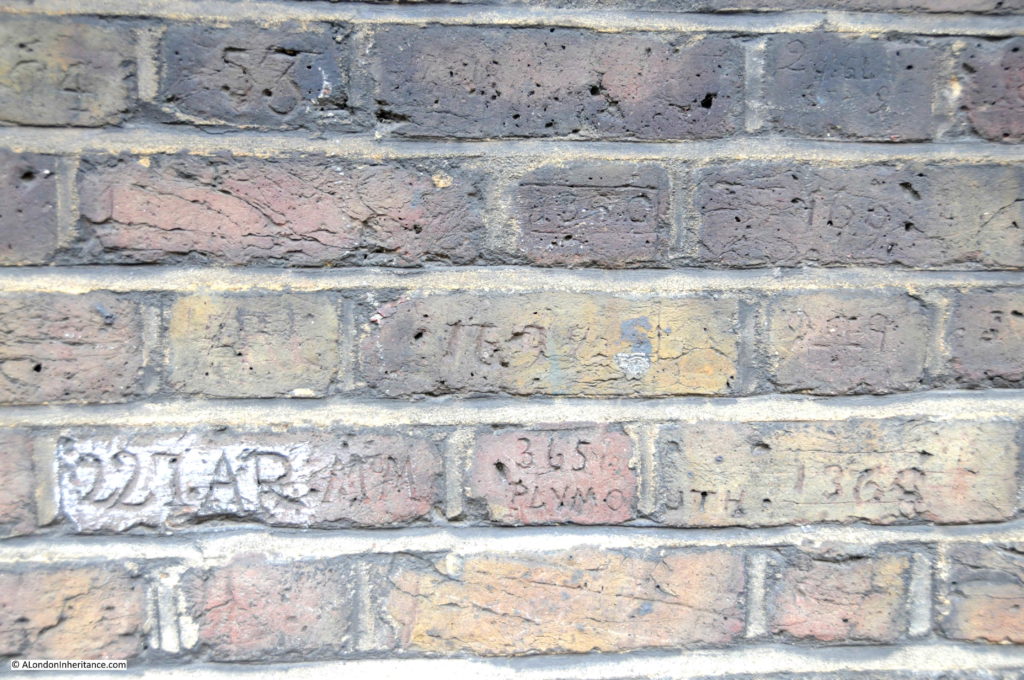

The presence of police officers in Myddleton Passage can be seen through “collar numbers” carved into a section of the boundary wall along Myddleton Passage.

The Survey of London identifies a number of the officers who recorded their numbers along the wall. One being Frederick Albert Victor Moore, from Cornwall, who joined G Division of the Metropolitan Police in 1886. Prior to his transfer to London he had served at the Devonport Naval Dockyard, and in Myddleton Passage recorded not only his London number, but also his original 365 PLYMOUTH number, seen in the middle of the second from bottom course of bricks in the following photo:

Fascinating to imagine Metropolitan Police Officers of the 19th century patrolling this lonely alley on a dark night, with the waters of New River Head just behind the wall.

Walk to the end of Myddleton Passage, stop off at the viewing platform then head north.

At the end of Myddleton Passage, we reach Myddleton Square, a large square with the church of St Marks, Clerkenwell in the centre. Both passage and square named after Hugh Myddleton.

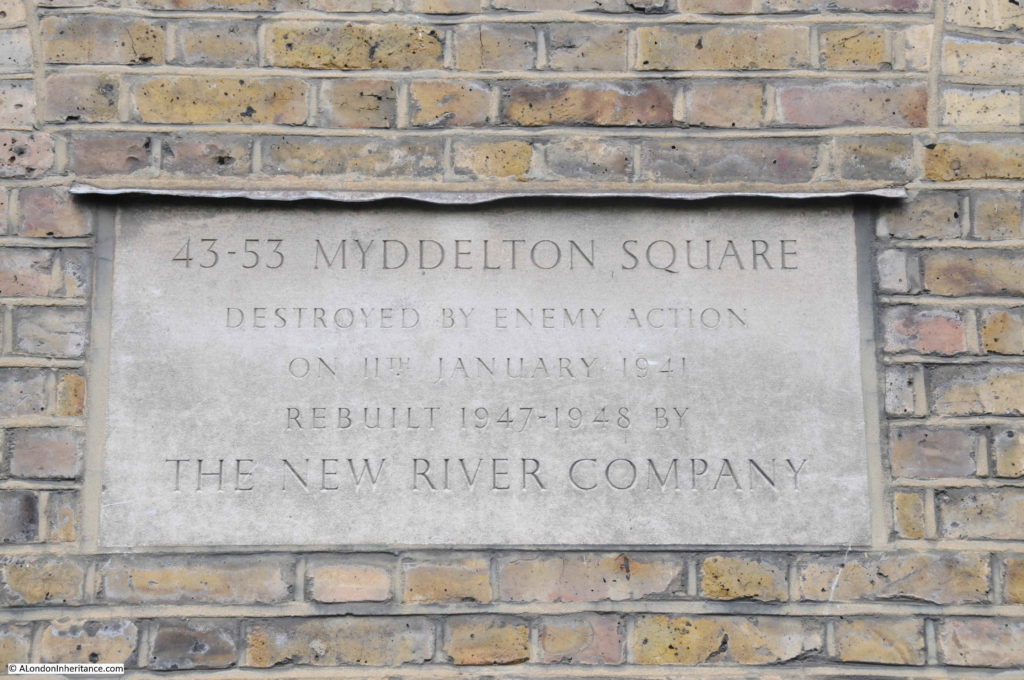

Along the northern terrace of Myddleton Square, there is a distinctive change in brick colouring:

Not due to cleaning, rather bombing of the site and a rebuild of the terrace as recorded on a plaque adjacent to the black door in the centre of the above photo:

The plaque records the New River Company rebuilt this section of Myddleton Square between 1947 and 1948, and it also gives a clue as to how the New River Company evolved.

The Metropolis Water Act of 1902 transferred the responsibility of the many local water companies serving London to the newly created Metropolitan Water Board. The New River Company ceased the role that it had been created for almost 300 year before.

As well as supplying water, the New River Company had long been a significant owner of land and properties, both along the route of the New River and the surroundings of New River Head. In 1904, the New River Company re-incorporated as a property company.

In 1974 the New River Company was taken over by London Merchant Securities, but still operated as a separate division.

Today, the New River Company is a subsidiary of the property company Derwent London plc (I am constantly fascinated by how you can still find evidence of centuries old institutions across London).

A turning off Myddleton Square is Chadwell Street – after one of the original Hertfordshire springs.

Leading north from Myddleton Square is Mylne Street.

Mylne Street is named after Robert Mylne (1733 to 1811), who became the New River Company’s second chief surveyor in 1771. Mylne had already worked on Blackfriars Bridge (completed in 1760), he was surveyor of St Paul’s Cathedral and worked on numerous canal and architectural construction and engineering projects.

I have a load of 1980s photos that we took around Clerkenwell and Islington, and one of the reasons for my visit to the area was to photograph the same locations today. The following is a photo from 1984 showing one of the first buildings in Mylne Street from Myddleton Square.

It is a lovely building, with ornate ironwork fronting the street, but what was of interest is the street name carved between the ground and first floors. Also, from the perspective of 2019, the parking meter that was once so common across London streets.

The same building in November 2019:

At the northern end of Mylne Street we reach Claremont Square. This was the location of the New, or Upper Pond. In a wonderful example of continuity of use, over 300 years later, the centre of the square is still occupied by a large, covered reservoir, with grassed, earth banks surrounding the centre of the square.

Lining three sides of the square are early 19th century terrace houses. Pentonville Road lines the northern edge of the square.

Steps leading up from Claremont Square to the top of the reservoir:

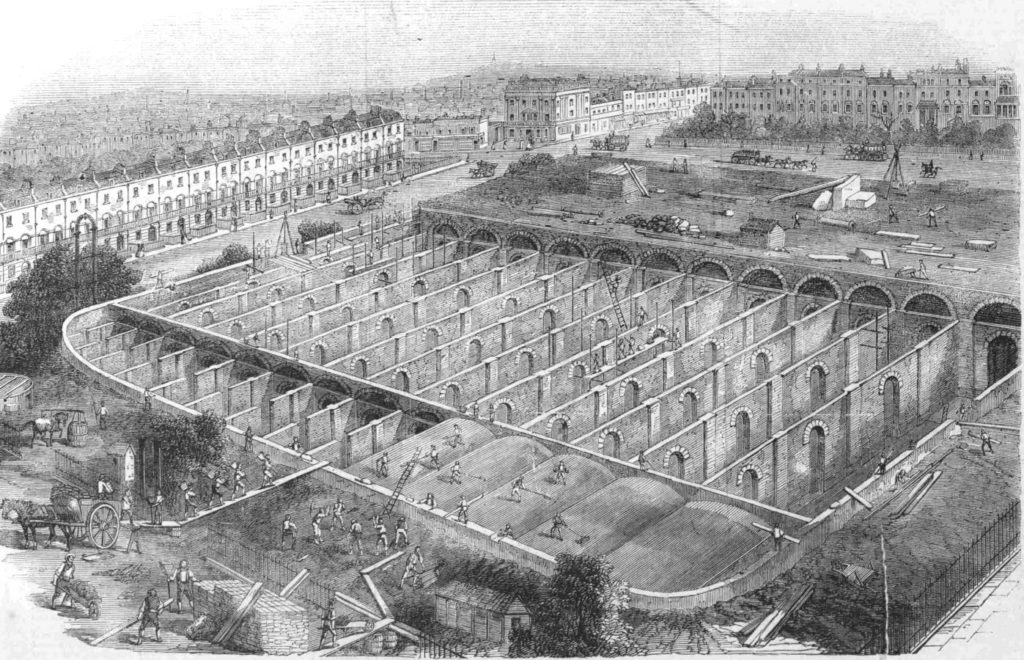

The original reservoir was uncovered, however as the reservoir contained filtered water ready for distribution to consumers, the Metropolis Water Act of 1852 required such reservoirs to be covered to prevent any form of contamination entering the water from the wider environment.

In the 1850s, the reservoir was drained, brick piers built, covered and turfed over. The reservoir was also raised in height to give a total depth of water of 21 feet, and the capability to hold 3.5 million gallons.

Four million bricks were used in the reconstruction and covering the reservoir, and the following print showing work taking place, and the internal construction provides a good view of how the reservoir was built and covered.

Whilst New River Head could provide water for large parts of London in the 17th and 18th centuries, new sources and reservoirs were being developed, including reservoirs in Stoke Newington, where the New River now terminates and feeds the east and west reservoirs just south of Seven Sisters Road.

The Claremont Square reservoir was already integrated into a wider water distribution network in the 19th century, as in the 19th century, large pipes had been installed between the reservoirs in Stoke Newington and Claremont Square, so the reservoir could be stocked with water from both New River Head and Stoke Newington.

Today, the reservoir is fed with water from the London Ring Main, and the reservoir was Grade II listed in the year 2000..

The western edge of Claremont Square is at the top of Amwell Street (named after one of the original Hertfordshire springs), so I turned into Amwell Street and headed south.

Passing the junction with River Street (after the New River) and Lloyd Baker Street (see my earlier post on the Lloyd Baker Estate), I reached the point where you can peer through railings surrounding the New River Head site, and see the base of the windmill that was built to pump water from New River Head to the Claremont Square Reservoir in 1709:

The plaque above the door reads:

“The round house, remains of the windmill used C. 1709 -1720 to pump water from the round pond to the upper pond (now Claremont Square reservoir)”.

Locks on the entrance gate between Amwell Street and the New River Head site – they really do not want you to get in:

Which is understandable, as New River Head is still a key location in the distribution of water across London.

In another fascinating example of how locations across London maintain a continuity of use across centuries, the information panel at the viewing point shows where a deep shaft at the New River Head site connects to the London Ring Main, a core part of the infrastructure that now distributes water across London.

Pumps raise water from the ring main for distribution via the Claremont Square reservoir.

As well as the London Ring Main interconnect, the New River Head site also hosts a bore hole used to extract ground water.

For centuries, water intensive industries such as breweries, tanneries etc. drained London’s ground water, resulting in an ever dropping level of ground water.

With the decline of these industries, ground water has been gradually rising. Whilst a good thing to return to natural levels, rising groundwater does create problems for the infrastructure now buried deep under London. For example, TFL has to pump 47 million litres of water a day from across the network, with 35 litres per second needing to be pumped from just Victoria Station.

The bore hole at New River Head is to the left of the old windmill base, but appears to be out of operation at the moment as stabilisation works are required, however when back in operation, the New River Head bore hole can extract between 3 and 3.46 million litres per day from London’s rising ground water.

Again, I have only scratched the surface of the history of the area and New River Head. Within the Round Pond, there is the Devil’s Conduit, a chimney conduit originally from Queen’s Square, Bloomsbury and moved to New River Head in 1927. The original 17th century oak room from the Water House building, built next to the Round Pond, and dating from around 1693, is now in the Metropolitan Water Board head office building (open during Open House, London).

Thames Water (the successor to the Metropolitan Water Board) have long left the New River Head offices, and are now based in Reading. The old head office building has been converted into flats.

To research this post, as well as walking the area I have used a number of excellent books, including:

- The New River by Mary Cosh

- The Survey of London, Volume 47 on Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville

- The History of the London Water Industry 1580 to 1820 by Leslie Tomory

- Online reports from Thames Water and TFL

- Online reports by the General Aquifer Research Development and Investigation Team

The book by Leslie Tomory is a fascinating read if you want to understand how the water industry developed across London from very simple beginnings, to an industry that could serve an industrialising and rapidly expanding city.