The City of London has been occupied in one form or another for around 2,000 years, and those centuries of occupation have left their mark, whether it is in the pattern of the streets, pushing the embankment wall into the river and reclaiming parts of the foreshore, churches, rising ground levels, and the buried remains of buildings along with the accumulated rubbish, lost possessions, burials and industrial waste of the centuries.

In today’s post, I am visiting two places where the remains of Roman occupation are on display. two very different structures and methods of display, but each telling a story of London’s long history, and how these remains have survived, and their discovery, starting with:

The Temple of Mithras

The Temple of Mithras was one of the major post-war discoveries in the City of London as archaeologists rushed to excavate sites, although they had very limited funds and time.

The Temple of Mithras tells an interesting story of Roman occupation of the City, post-war archaeology, and how we value such discoveries.

The Temple of Mithras is now on display at the London Mithraeum, built as part of the construction of Bloomberg’s new European headquarters.

The remains of the temple have been displayed in a really imaginative way. Subtle lighting, a recreation of the sounds of activity in the temple during the Roman period and an image of the god Mithras overlooking the temple from the location of the apse and the block where the final altar in the temple was located.

The view on entering the Temple of Mithras:

The Temple of Mithras was discovered in 1954 by the archaeologist W.F. Grimes.

The post-war bomb sites across the City of London offered a one off opportunity to excavate and explore for remains of occupation of the City from previous centuries, and in 1946 the Society of Antiquaries of London sponsored a short trial session, and then established the Roman and Mediaeval London Excavation Council in order to more formally establish a long term series of excavations.

These continued through to December 1962, with the majority being led by W.F. Grimes.

There were two main challenges to this work, both of which almost resulted in the failure to discover the Temple of Mithras – money and time.

The Excavation Council was able to raise funds from private donors, and in 1968 Grimes published “The Excavation of Roman and Medieval London”, a brilliant book providing an initial record of the work between 1947 and 1962. In the back of the book is a list of donors, which included the Government Ministry of Works (£26,300) and the Bank of England (£2,750) as the top two donors, down to two pages of donors who contributed £1. There were also a large number of donors who gave less than a £1, but were not recorded in the book.

By 1954, donor funds were growing short, and in the many newspaper reports of the discovery, it was reported that “Mr. Grimes had only found the temple because, after private subscriptions fell off, a grant from the Ministry of £2,000 a year had kept him going”.

There was also the challenge of time, and the walls of the temple were found towards the very end of the period agreed with the developer to excavate the site. Such was the importance of the find, that the developers allowed an extra two weeks for excavation.

At the temple today, there are two walkways along the sides of the temple, and at the end of these, we can look back at the interior of the temple:

From the location of the apse, and where the altar was located:

The area that was being excavated, and where the Temple of Mithras was found, was a large almost triangular plot bounded by Queen Victoria Street in the north, Budge Row to the south and Walbrook to the east. Budge Row sort of exists, but is now a covered walkway between two sections of the Bloomberg building, and appears to be called the Bloomberg Arcade.

The importance of the site was that it was part of the valley of the old Walbrook stream, and at the time, very little was known of the extent and nature of the stream and the surrounding valley.

Prior to the temple being found, work had focused on identifying the location of the stream, and sectional cuts were taken across the site which found that the Walbrook was in a shallow basin of around 290 to 300 feet across, and that the stream was around 14 feet wide and relatively shallow.

Excavations also found that the process of raising the land surface had started at a very early date, with dumping of material in the basin of the stream, mainly on the western edge of stream.

A number of timber deposits were found, mainly floors, and also contraptions such as guttering, all to deal with the wet conditions of the land surrounding the Walbrook stream.

There were very few stone structures, and apart from the temple, only one other stone building was found on the site, so although the site was in the centre of Roman London, it was very different to what could have been expected, with no concentration of stone buildings, and probably an area which had a stream running through, and was wet and marshy.

The main body of the temple was found to be rectangular and around 58.5 feet long and 26 feet wide, and consisted of a semi-circular apse at the western end.

In Grimes book, he mentions that the eastern end of the building consisted of a narthex or vestibule, which projected beyond the side walls of the building, and that part of this vestibule lay, and in 1954 at the end of excavation, remained under the street Walbrook. I need to find out if that is still the case, or whether it has since been excavated.

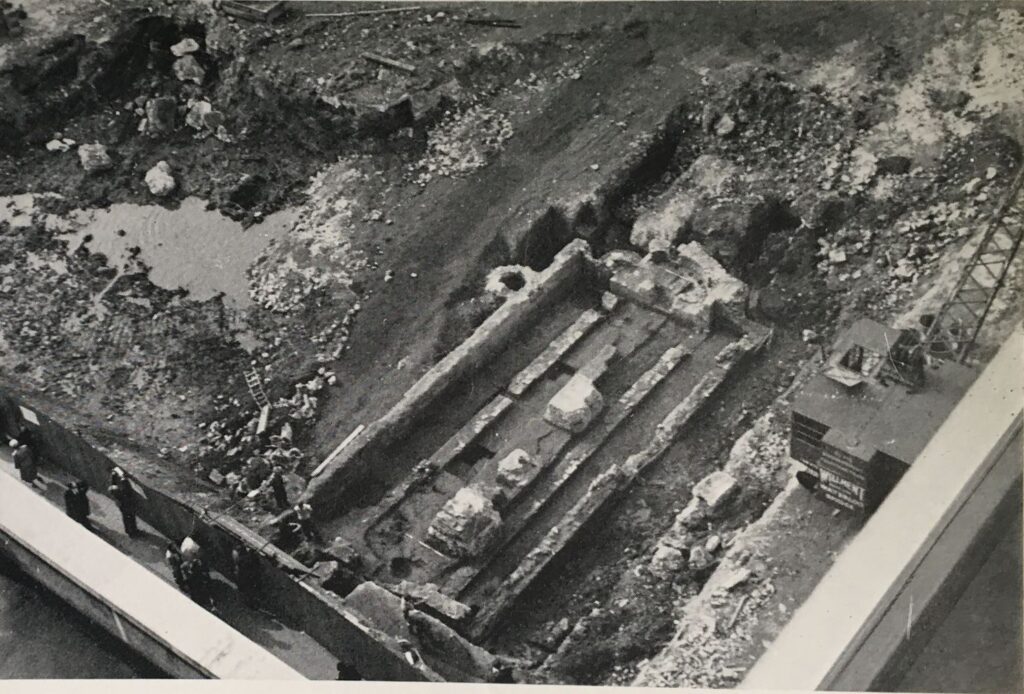

Photo from the book “The Excavation of Roman and Medieval London” by W.F. Grimes showing the Temple of Mithras as finally excavated. The photo was taken from the north east, so would have been next to the street Walbrook:

The photo below is a view of the apse, which was at the western end of the temple, the upper right of the temple in the photo above:

The excavated temple was opened to the public for a short period between excavation and the removal of the stones, and very long queues formed to get a glimpse of this Roman survivor:

However, you can forget all the stories of polite British queuing, as the News Chronicle reported on Wednesday the 22nd of September 1954: “Sightseers Storm the Cordon. When darkness came, hundreds were still queuing. They got angry and dozens stormed through police barriers to see the Temple of Mithras.

Instead of the 50 to 500 people expected at the half acre bomb site near Mansion House, where last week a marble head of the god was unearthed, there were 10,000.

Police reinforcements were called as they milled around. At 6:30 when the site was due to close, thousands were still queuing. Then the contractors – who are to build London’s tallest office block on the site – decided to keep it open till seven.

There was an angry scene when the police announced half an hour later that no more people could be allowed. By then, darkness was falling and hundreds were still queuing. The disappointed crowd shouted ‘We’ve been waiting more than an hour’.”

Looking back at the apse:

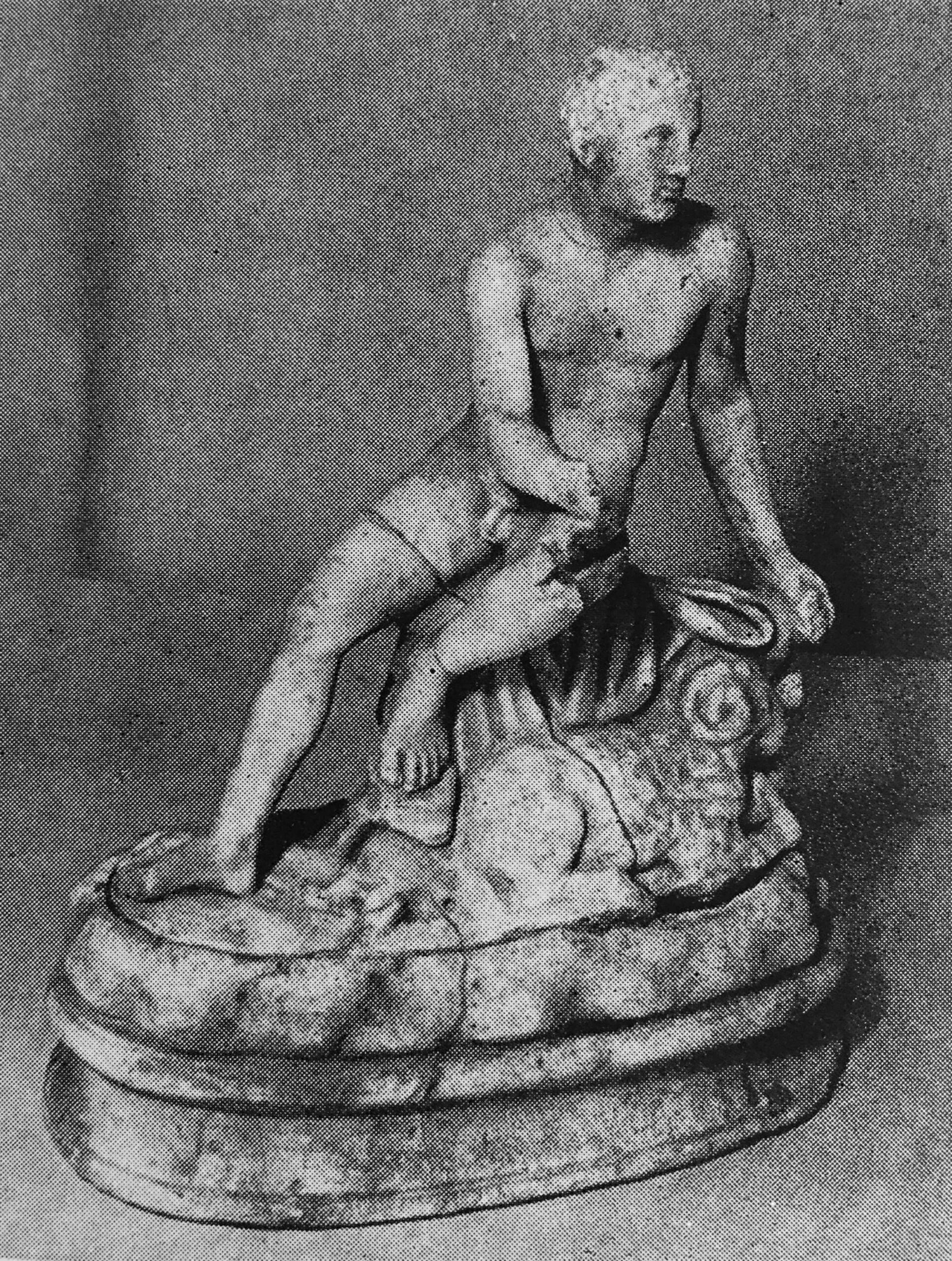

There were a number of finds at the site of the temple, including, Mercury, a messenger god, seated on a ram:

Mable head representing the godess Minerva:

And then there was the head and neck of Mithras. This was found by one of the excavators on the site, Mrs. Audrey Williams, and I found a photo of her, holding the head of Mithras, in the book “Buried London” by William Thomson Hill (1955):

Audrey Williams was a highly experienced archeaologist, but was, and still is, rather unrecognised.

She was mentioned in some newspaper reports about the temple, a typical report being “Excavators were about to put aside their trowels when Mrs. Audrey Williams, second-in-command to Mr. W.F. Grimes, director of the London Museum in charge of the excavations, scraped the side of a marble cheek”.

There is a biography of Audrey Williams on the excellent Trowel Blazers site, which also records that it was Audrey who was on site every day, and her work makes up much of the archive as Grimes was also working on another site.

Mithras was one of many Roman gods, and the cult of Mithras started in Rome and eventually spread across the Roman empire. It seems to have attracted those who were administrators, merchants and soldiers within the empire, and meetings were held in temples, often below ground. Dark, windowless places, which the presentation at the London Mithraeum demonstrates well.

The location of the temple, on the banks of the Walbrook stream would have added an extra dimension to the place.

At the end of the time available for the excavation, there was concern about the future of the temple, and whether the cost of preserving or moving the temple would be supported by the Government. A solution was found thanks to the owners of Bucklersbury House, the building that would be constructed on the site, as reported in the Courier and Advertiser on the 2nd of October, 1954:

“The Temple of Mithras, recently uncovered in the City of London, is to be moved, brick by brick, and re-erected on a site 80 yards away.

A Ministry of Works statement yesterday said – It has been decided that the cost of preserving the remains of the Temple of Mithras in its present position, estimated at more that £500,000 cannot be met from public funds. Happily, however, Mr. A.V. Bridgland, and the owners of the site of Bucklersbury House, have made a most generous proposal, which the Government believe will be widely welcomed.

The temple is to be moved from its present low level and put up again in an open courtyard on the Queen Victoria Street front of Bucklersbury House site.

Estimated cost of the removal is £10,000 which is to be borne by the owner of the site.”

Photo from the book “Buried London” by William Thomson Hill (1955), showing the Temple of Mithras being rebuilt in its temporary location in October 1954 before being moved to Temple Court in Queen Victoria Street where it was put on open air, public display in the early 1960s:

It is interesting to speculate just how original many of these early buildings remain.

Grimes, in his book states that the individual stones of the temple were not numbered, rather the walls were photographed and the rebuild of the temple was based on these photos.

The reconstruction in the London Mithraeum also used new mortar between the stones, but using a formula which would have been used at the time..

The Temple of Mithras remained in the open until the Bloomberg building was constructed on a large site, which included the location of the post-war Bucklersbury House.

The Temple of Mithras is not in exactly the same position as when discovered as it is a small distance to the west, but it is close enough, and at the level below ground to its original location.

There is also an exhibition of many of the finds from the site, including a steelyard balance and weights, used for measuring the weight of goods which would have been suspended from the hook on the right:

And rings:

The Temple of Mithras is well worth a visit. As well as the physical remains of the temple and finds from the site, the presentation as part of the London Mithraeum provides a good impression of how the temple may have been used, when it was sitting on the banks of the Walbrook, some 1800 years ago.

Details can be found at the site of the London Mithraeum, here.

There is a British Pathe film of the discovery here.

The Vine Street Roman Wall

The City Wall at Vine Street is the name of a new exhibition of part of the Roman London wall in the basement area of a new building complex that seems to consist of student accommodation and offices.

Although the name of the exhibition includes Vine Street, the entrance is at 12 Jewry Street. The overall building complex sits between Jewry Street and Vine Street.

After entering at ground level, a walk down to the lower level reveals the section of London wall:

The face of the wall in the above photo is the side that was on the inside of the City of London.

The presentation of the wall is really very good, because it shows not just the Roman wall, but also tells the story of how it has survived for so long.

Today, in preparation for a new building, the existing building on the site is usually fully demolished, down to a big hole in the ground. The new building is then constructed without any use of parts of the structure of the previous building.

This is starting to change, for example the old BT building on Newgate Street is being completely remodeled, and the building’s structural frame will be mainly retained in a building that will look completely different from the outside.

In the past, where there were existing walls, it was often very cost effective to incorporate these into a new building. I have written about a couple of examples in previous posts such as St. Alphage on London Wall, the Bastions and Wall between London Wall and St. Giles, Cripplegate, and the Roman Wall on Tower Hill, and it was only by being included in much later buildings that these earlier structures have survived.

The Roman Wall did continue in use during the medieval period, when medieval brick and stone work extended the height of the wall as the ground level in many parts of London was gradually rising, but it was becoming redundant.

The City was expanding outside the wall, so although parts were demolished and stones often reused as building material, other parts of the wall were built against, and included in new structures, and the section on display became part of a number of buildings on the site.

In the construction of a new building on the site in 1905, the wall was exposed, and thankfully it was preserved in the basement.

In the above photo, the black piers supporting the wall are from the 1905 construction, and underneath are jacks installed as part of the build of the current building on the site.

And to the left of the Roman wall in the above photo, and more clearly in the photo below, can be seen the walls of the last building on the site, and how they butted up to the Roman wall:

Walking to the other side of the wall and we are now presented with the wall that would have faced outside of the City:

And we can also see the remains of a bastion, a small building on the side of the wall, usually with a semi-circular end, that was used for defensive purposes:

As with the London Mithraeum, there is a large display of the many finds from the site and surrounding area:

The finds represent the whole period that the wall has stood on the site. As the level of the ground increased in height, centuries of London’s rubbish, broken pottery and china, accidently lost personal items, animal bones and the waste from industrial activities have all accumulated:

One of the finds is a bit of a mystery. It was found further to the south in 1957, during construction work in Crosswall. It appears to be a stele (an upright stone slab bearing a relief and / or an inscription, and often used as a gravestone):

It is believed to have come from the eastern Mediterranean and dating from around 200 BC, with the inscription perhaps being added a couple of centuries later.

It is unclear how the stone came to be in the City of London, and one of the theories put forward was that the stone was brought to London many centuries later during a Grand Tour, when those rich enough and still relatively young, would embark on a tour through the major cultural and historical centers of Europe and bring back artifacts from their travels.

The Vine Street Roman wall is also very well worth a visit. A different form of presentation to the Temple of Mithras, but it shows how the wall survived by becoming part of much later buildings.

Details can be found at the website of the Vine Street Roman Wall, here.