In the summer of 1980, I went for a walk along the South Bank, taking a few photos of the area, and of the extension of the embankment and walkway onward from Waterloo Bridge.

Last Saturday, the weather was perfect and the light ideal for photography. The sun was out and unusually, there was no haze in the sky, so 39 years later I took another walk along the South Bank to photograph the same scenes and consider the changes.

I walked down from Westminster Bridge, straight into the crowds in front of County Hall and through the queues waiting for a ride on the London Eye.

In 1980, this was the view along the South Bank, in front of Jubilee Gardens and looking towards Hungerford Bridge.

The same scene today (I should have been slightly further along, but the space was occupied by a street entertainer and large crowd).

The South Bank today is an extremely busy part of London. The wonderful weather and long Easter weekend added to the crowds, but walk along here nearly any weekend and there are crowds of people walking along the southern bank of the river.

In 2017, the Southbank Centre (the Royal Festival Hall and Queen Elizabeth Hall) was the UK’s seventh most visited attraction with a total of 3.2 million visitors. By 2018, the London Eye had rotated 70 million visitors over the previous 18 years.

It was very different in 1980, as whilst a popular place to walk. County Hall was still the GLC seat of government, not the hotel and site of tourist attractions it is today. The river walk ended at the National Theatre and the London Eye was still many years in the future.

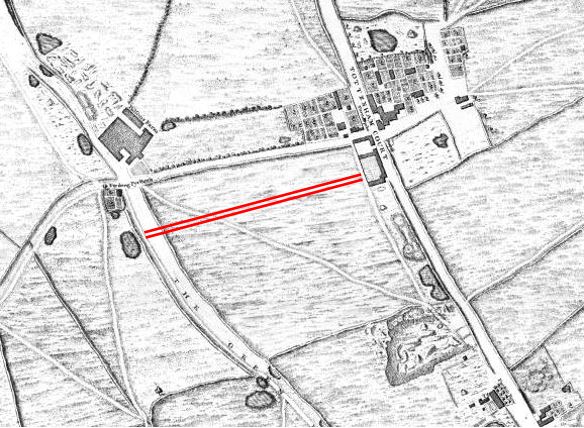

The stretch of the embankment between Westminster Bridge and Waterloo Bridge was part of the development work for the 1951 Festival of Britain which occupied much of this space.

The South Bank does provide some superb views across the rivers, many of these views must have been photographed millions of times by the stream of visitors.

In 1980 I took this photograph of the view across the river to the Palace of Westminster.

The London Eye and the river pier have changed both the views and the numbers of visitors to the South Bank. The same view in 2019.

Looking towards Hungerford Railway Bridge in 1980:

In 1980 there was a single, narrow walkway running along the eastern side of the bridge so not visible in the above photo. In 2002, the Golden Jubilee foot bridges were opened, one on either side of the bridge, and their concrete piers and white supports have changed the view of the bridge as shown in the 2019 photo below.

The other significant change between the above two photos is the building above Charing Cross Station. The station is on the left side of the above two photos, and in the first photo the original station buildings can be seen at the end of the bridge, whilst in 2019, the office blocks that were built above the entrance to the station obscure the view of the station buildings.

The South Bank is a magnet for street entertainers. As well as the usual floating Yoda’s, a wide variety of street entertainers attract large crowds, and frustratingly the space below was where I wanted to take the first comparison photo.

Passing underneath Hungerford Railway Bridge, we find the Royal Festival Hall. Built for the Festival of Britain, and the only permanent structure left over from the festival on the South Bank. It is still a magnificent building, however the immediate surroundings of the building have changed significantly.

In the photo below, I was standing at the end of the footbridge, looking along the front of the Royal Festival Hall and the space between building and river.

This is the same view today (I could not get to the exact same viewpoint as the original walkway has been demolished).

The grass slope running from the river walkway down to the lower level of the hall has been replaced by steps and restaurants now run along almost the entire length.

I have written about this area a number of times as my father photographed the site of the Royal Festival Hall and the streets between the river and Waterloo Station just before they were demolished to build the Festival of Britain.

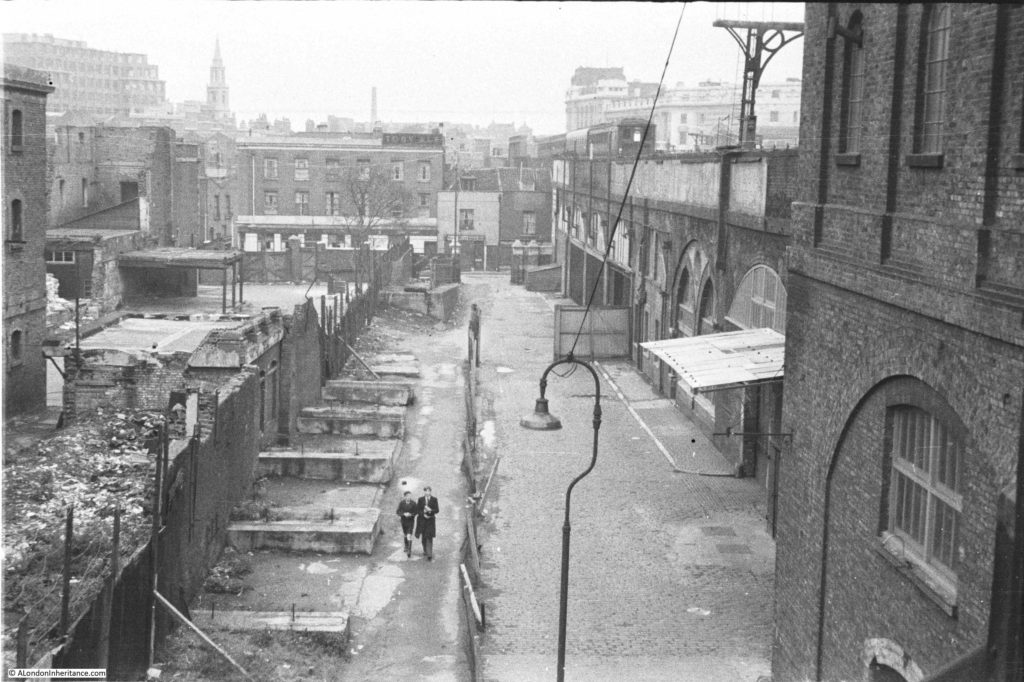

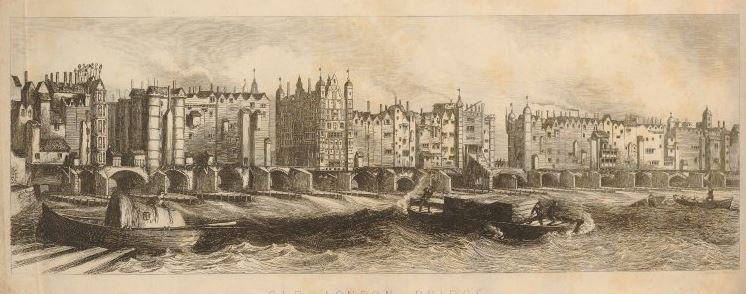

The following photo is one of my father’s, taken from a building at the end of Hungerford Bridge, looking south towards Waterloo Station.

In 1980 I took the following photo of the same view:

In 2019, the same scene is shown in the photo below (I could not get to the same position as for the 1980 photo otherwise I would have been standing in among the restaurant tables with a very limited view).

The three photos above symbolise what I really enjoy about this project. My father started photographing London in the late 1940s. I started in the 1970s and it is fascinating to continually watch and photograph the city as it evolves.

The view looking from the eastern end of the Royal Festival Hall.

As part of the Festival of Britain, a pier was built to allow visitors to arrive and depart by river. An updated version of the Festival Pier is still in operation.

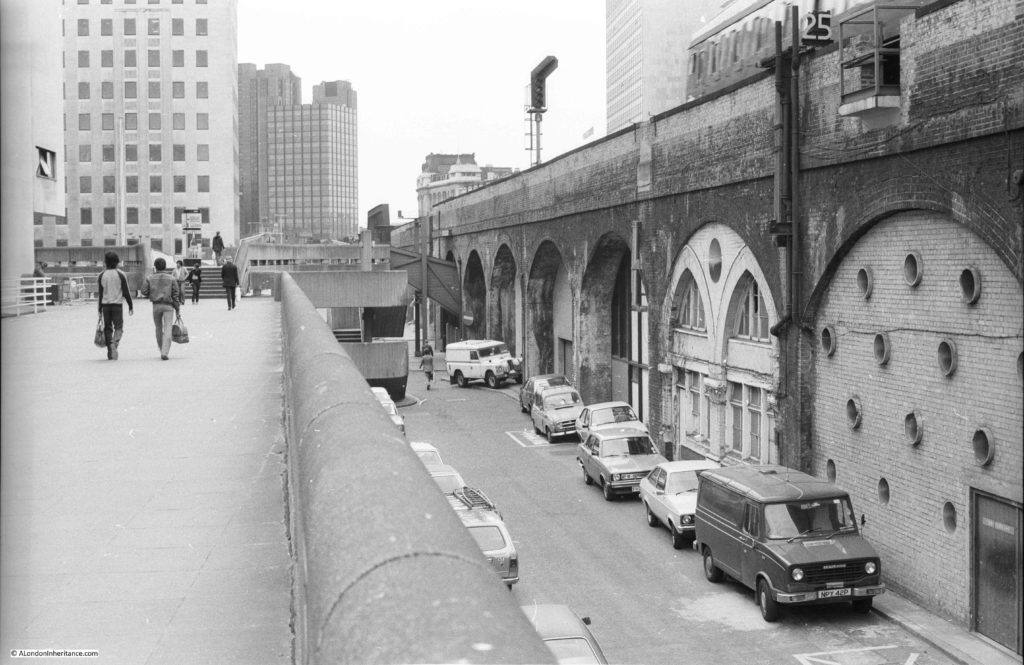

The view from Waterloo Bridge in 1980, looking towards the City.

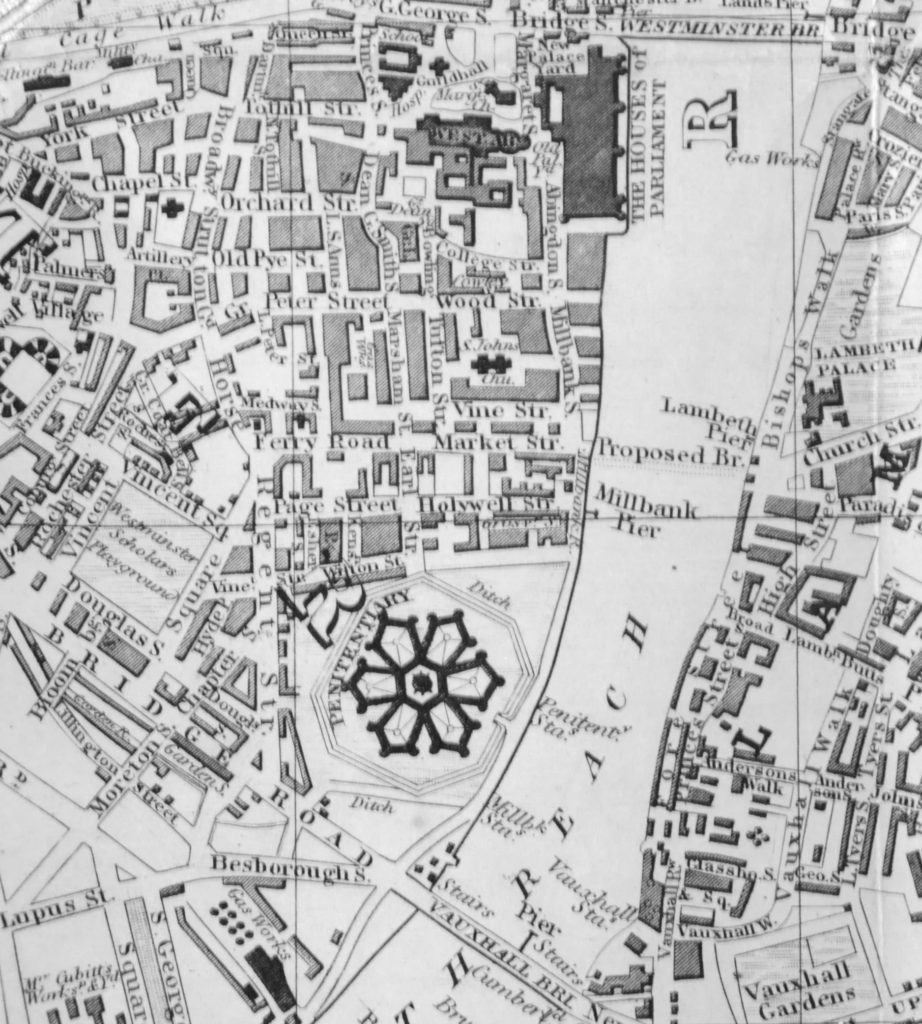

In 1980, the South Bank river walkway ended by the National Theatre. After the Festival of Britain there were plans to develop the area to the east of the Royal Festival Hall as a cultural centre.

The London County Council developed a master plan for the site in 1953, and it was this plan that gave the name South Bank. The plan identified a programme of development for the following 25 years and this resulted in the National Film Theatre (1956-8), Queen Elizabeth Hall complex (1963-8) and the National Theatre (1976).

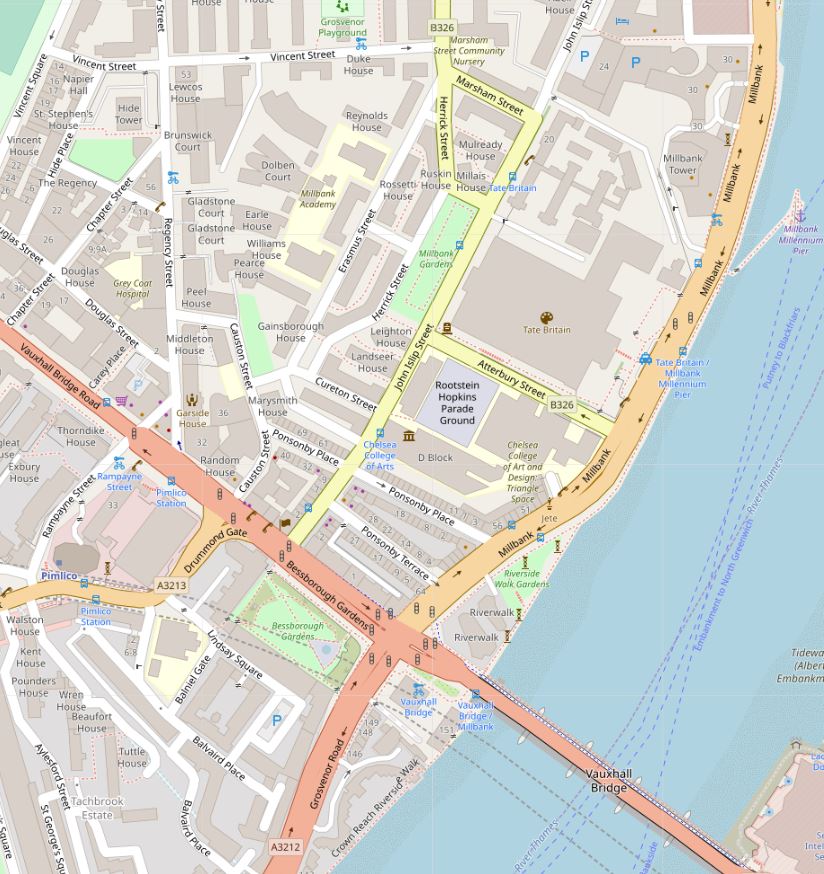

The South Bank further east from the National Theatre would be commercial, but the long term plan was for a single embankment walkway stretching from Westminster Bridge to Tower Bridge. This would be developed over the following decades, and in 1980, the first stretch extending eastwards from the National Theatre was being built.

The same view in 2019.

A better view of the works in 1980 is shown in the photo below. The National Theatre is on the right. The building under construction to the left of the National Theatre was being built as offices for IBM.

The National Theatre and IBM buildings have a similar style and they were both the work of the architect Denys Lasdun.

The London Weekend Television building is the tower block closest, whilst the tower furthest from the camera was Kings Reach Tower, occupied by the IPC publishing company.

In the above photo, the extension of the embankment and walkway can be seen as the very clean white stone, compared to the original embankment to the right.

The same view today is shown in the photo below. The stone of the embankment extension has now been weathered and blends in with the original. Kings Reach Tower has been vacated by IPC and has been converted to apartments, with several floors added to the top of the original tower.

The 1980 view across the river from Waterloo Bridge to the City. The three towers of the Barbican are on the left and the relatively new Nat West Tower stands tall in the centre of the City.

The same view in 2019. the Barbican towers can still be seen, however the original Nat West Tower has now been dwarfed and almost concealed by the many new tower blocks that have been, and continue to be built.

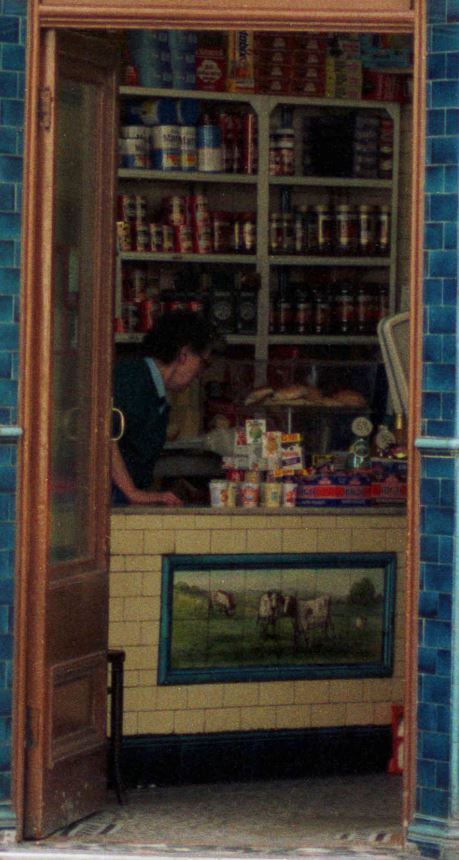

The walk along the South Bank from Waterloo Bridge to Blackfriars Bridge, whilst not as busy as the length between Westminster and Waterloo Bridges, is still busy with walkers. On a warm and sunny spring day, food traders were being kept busy.

Although there is always an option to get away from the crowds at low tide.

Sand sculpture on the Thames foreshore.

Getting closer to Blackfriars Bridge, and the latest construction that will subtly change the river can be seen. This is one of the construction sites for the Thames Tideway super sewer, and when finished, will be the site for an embankment extension into the river, covering the access shaft.

Reaching Blackfriars Bridge, I walked a short distance along the eastern side of the bridge, to take a photo from the same position as I took the following photo in 1980.

This short space of land is between the road bridge, and to the left the rail bridge, that carried the rail tracks over the river to Blackfriars Station. In 1980, this space was still many years from being part of the walkway along the southern bank of the river.

One of the original pier’s from the railway bridge can be seen on the left. On the right are steps which provided direct access to the foreshore.

The 2019 photo of the same scene is shown in the photo below.

The steps that once led directly down to the river have now been blocked off. The walkway along the river now runs underneath the scaffolding, as this part of the walkway seems to be a continuous construction site.

The large building behind the railway viaduct, covered in sheeting can just about be seen in the 1980 photo. This was built as a cheque clearing facility for Lloyds Bank and also operated as a Data Centre for the bank. In the last few years it was used by IBM, but is now being demolished to make way for a number of office and apartment towers.

Despite the crowds, I really enjoy a walk along the South Bank and London always looks at its best when the sun is shining and the sky is clear. There is something about walking alongside the river and watching the changing relationship between the city and the river.

The South Bank continues to evolve. New apartment towers are rising adjacent to the Shell Centre office block. The Lloyds building next to Blackfriars Bridge will be replaced by more tower blocks and there have been plans for more towers adjacent to the old London Weekend Television tower block.

It will be interesting to see what the area looks like in another 39 years – although I very much doubt it will be me taking the photos.

Some other posts as I have written about the area:

Building the Royal Festival Hall

A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Downstream Circuit

A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Upstream Circuit

A Brief History Of The South Bank

Tenison Street and Howley Terrace – Lost Streets On The Southbank