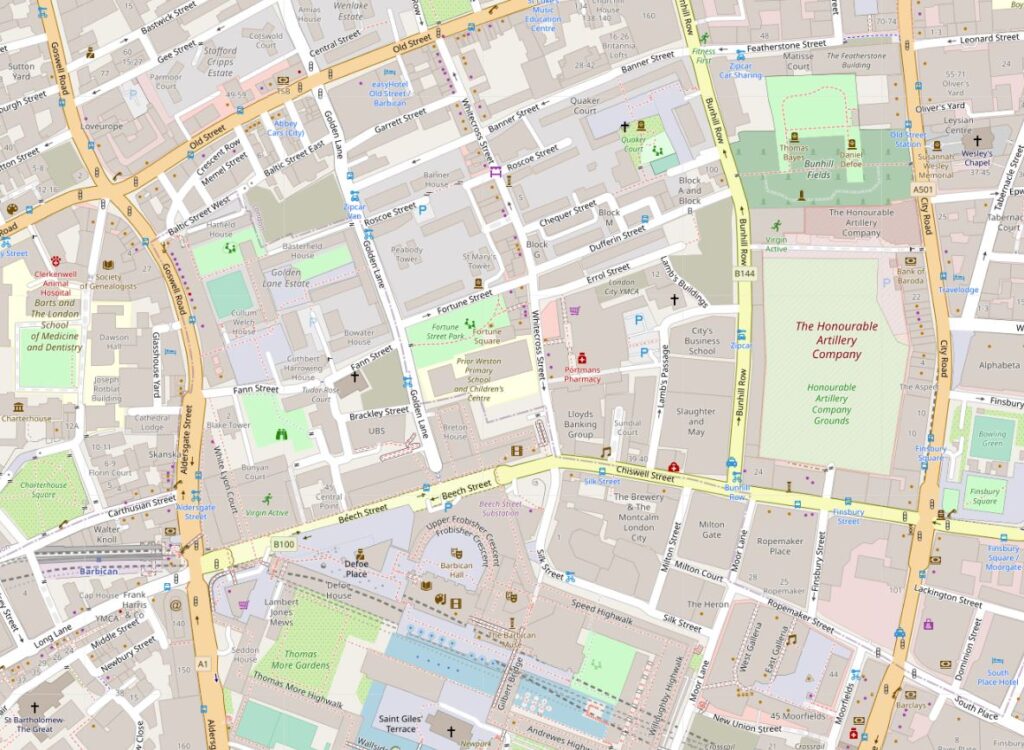

Whitecross Street runs between Old Street and Beech / Chiswell Streets, just north of the Barbican.

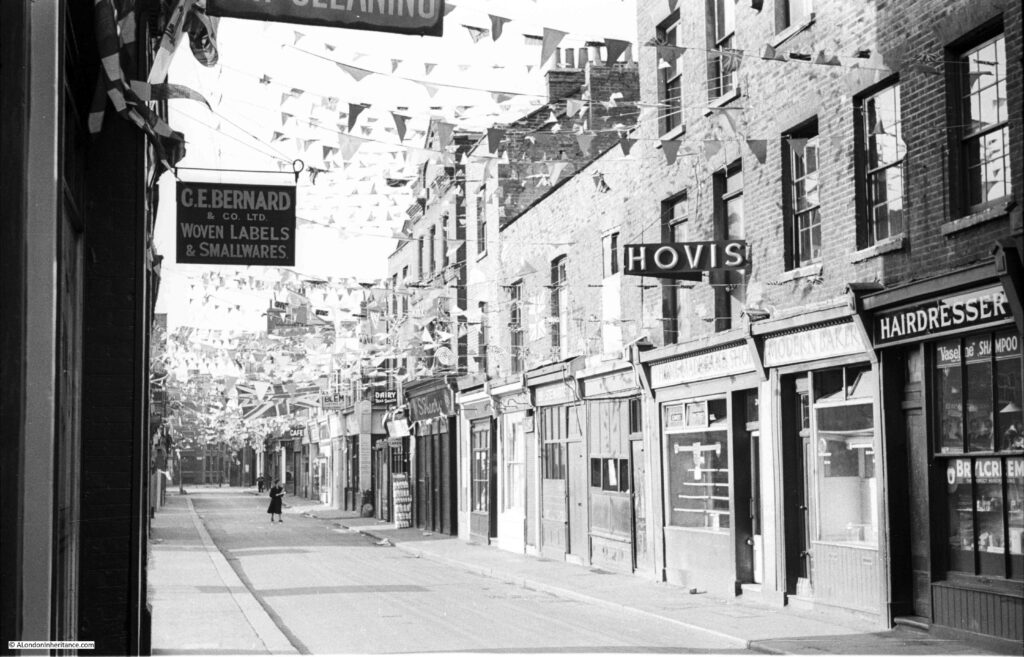

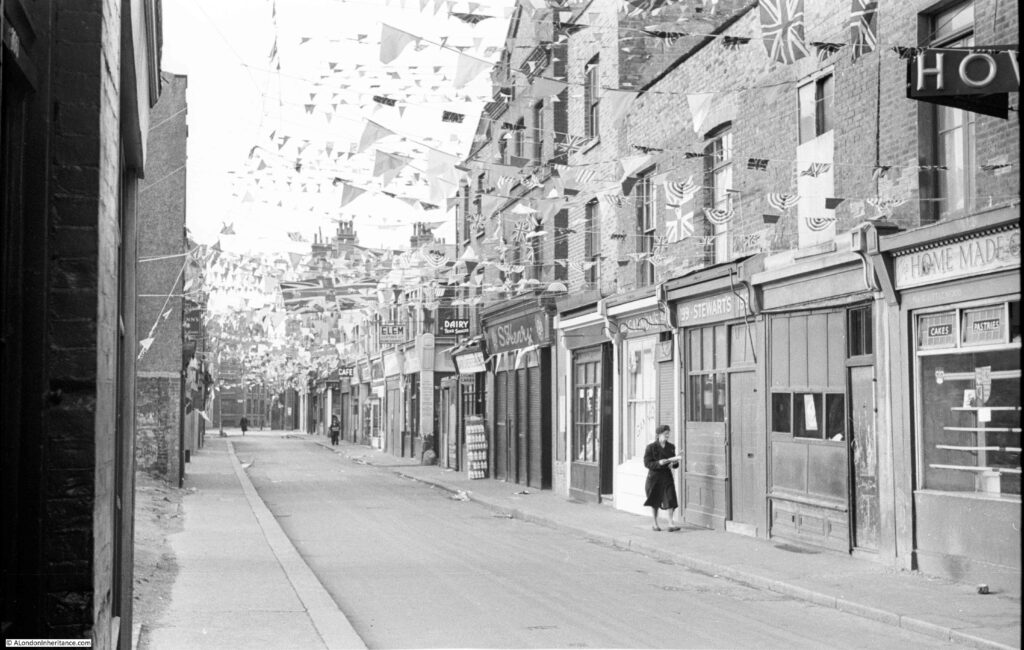

Many of my father’s photos were taken on bike rides around the city, early on a Saturday or Sunday. This worked due to periods away on National Service, work during the week, and other commitments. Early on Sunday, 31st May 1953 he was at the northern end of Whitecross Street and took the following photo looking south along the street:

One lunch time a couple of weeks ago I was in the area, and the following photo shows the same view as the above, sixty eight years later:

My father’s photo was one of a number he took on the same day in the area of Whitecross Street and also in Hoxton. The 1953 photo was taken a couple of days before the Coronation of Elizabeth II, on Tuesday, 2nd June 1953, and this explains the flags and bunting across the street.

A second photo, a short distance further into Whitecross Street. I suspect he was waiting for the woman to walk further up the street to add a focal point to the photo:

The terrace of buildings on the right of the photo have changed in the years between the two photos. The one building that confirms the two views are of the same street is the building with the pediment (the triangular shaped top to the wall) about two thirds of the way down on the right of the street.

Comaprison of the photos also shows that you cannot always trust the age of buildings at first sight. In the above 1953 photos, if we walk towards the camera from the pediment building, there is a narrow, three storey building with a single window at each floor. There is then a terrace of three houses / shops of two storeys, with a shop at ground level and single window / storey above each shop.

in the 2021 photo, this terrace has had an additional floor added to create a three storey terrace along the western side of Whitecross Street.

I have marked how the terrace has changed in the following photo, with the red line indicating the 1953 height of the buildings.

In 1953, the shops were the type of local shop serving the daily needs of those who lived in the area. The following is an extract from the second photo. Note the rack of milk bottles standing outside the dairy:

Today, there is a more diverse range of shops, and what was obvious during my walk along Whitecross Street was that the food market running down the centre of the street now serves the local working population, as the street was crowded with those out to buy their lunch.

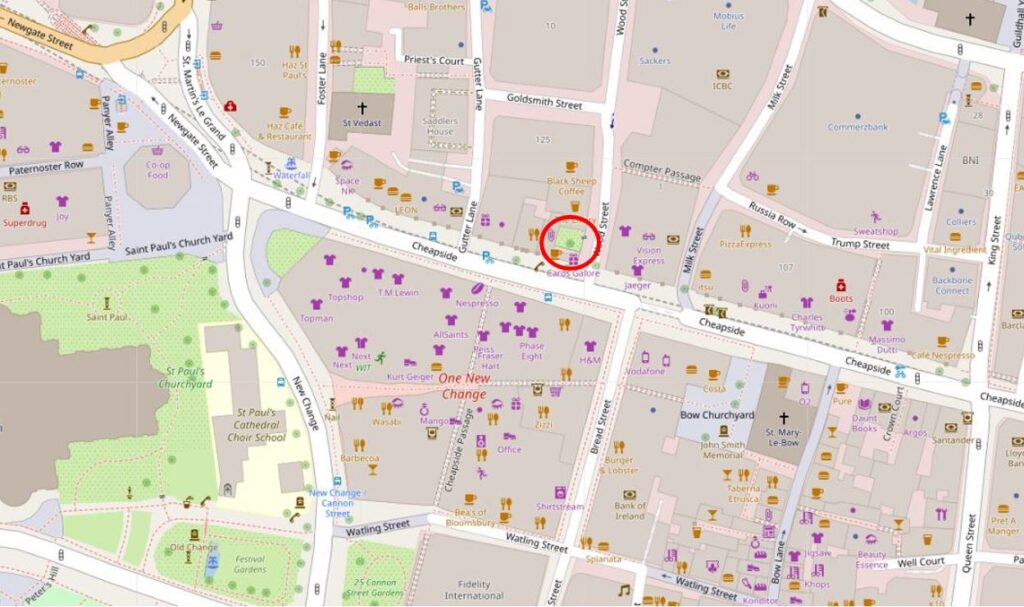

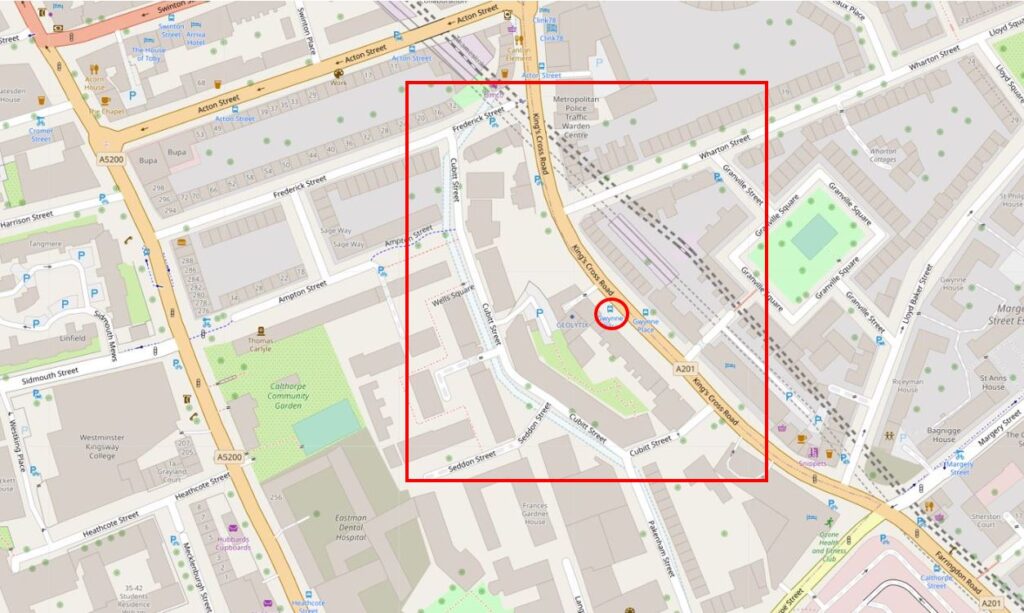

Whitecross Street can be found just north of the Barbican, linking Beech / Chiswell Streets at the southern end with Old Street to the north. In the following map, Whitecross Street is the street running vertically, in the centre of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

Whitecross Street was originally much longer than it is now, and it’s southern end was in the heart of Cripplegate. Considerable damage during the last war, and the construction of the Barbican estate has erased roughly one third of the original street.

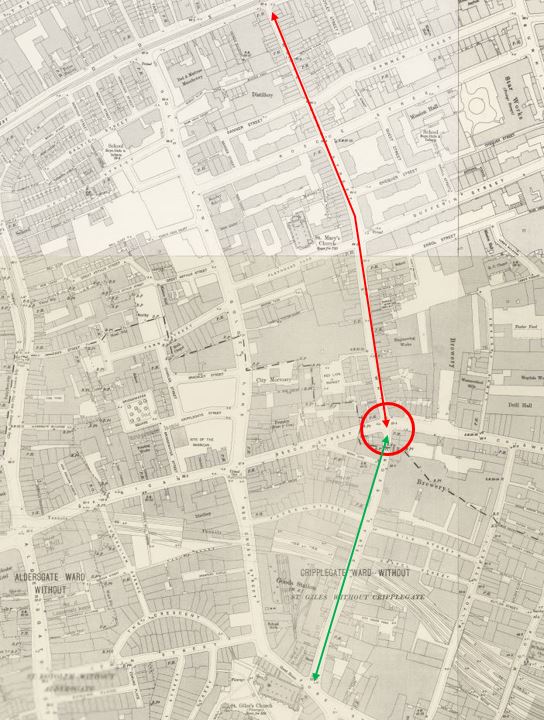

In the following extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey Map, I have highlighted the street we can walk today by the red arrow (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’.

The green arrow identifies the missing third of Whitecross Street. Today, a short section is now Silk Street before it terminates at the Barbican.

In the red circled area in the above map, there is the PH symbol for a pub on the corner of the lower section of Whitecross Street. The pub, the Jugged Hare, is still there today as shown in the following photo. Originally, Whitecross Street continued to the right, however this has now been renamed Silk Street as it curves to the north of the Barbican to Moor Lane.

As can be seen in the 1894 map, Whitecross Street originally joined Fore Street at the north east corner of St Giles, Cripplegate.

In the following photo, this would have been just behind and to the left of the car, and Whitecross Street would have run in front of / underneath the Barbican apartment block Gilbert House, the large block on the left of the photo.

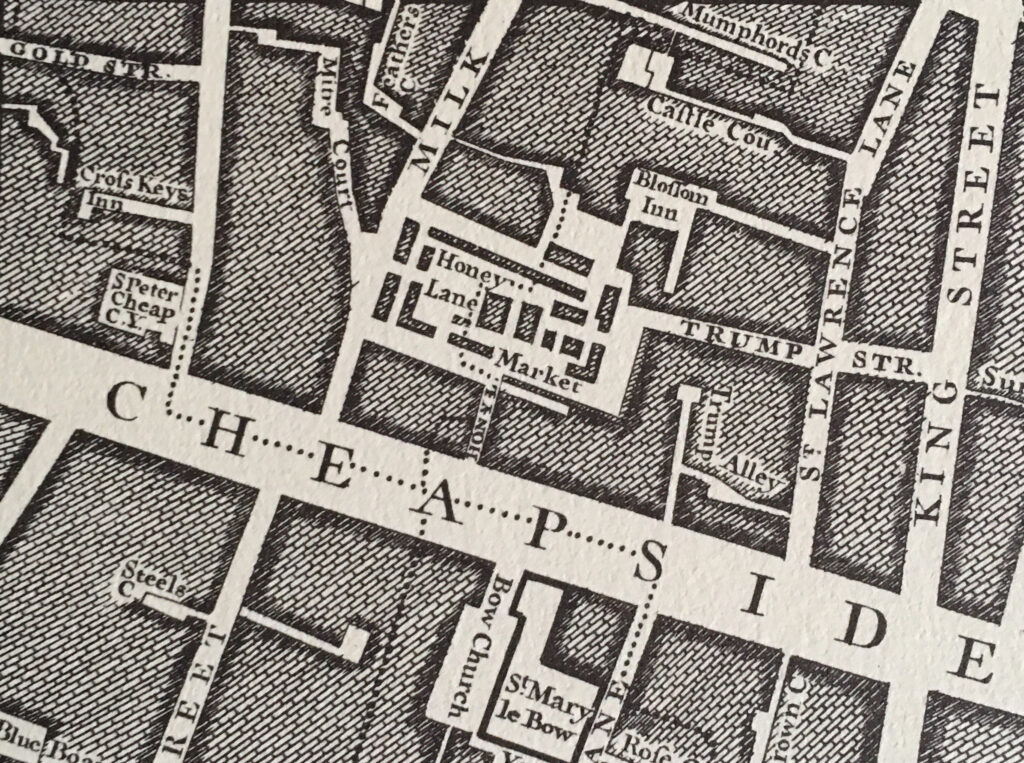

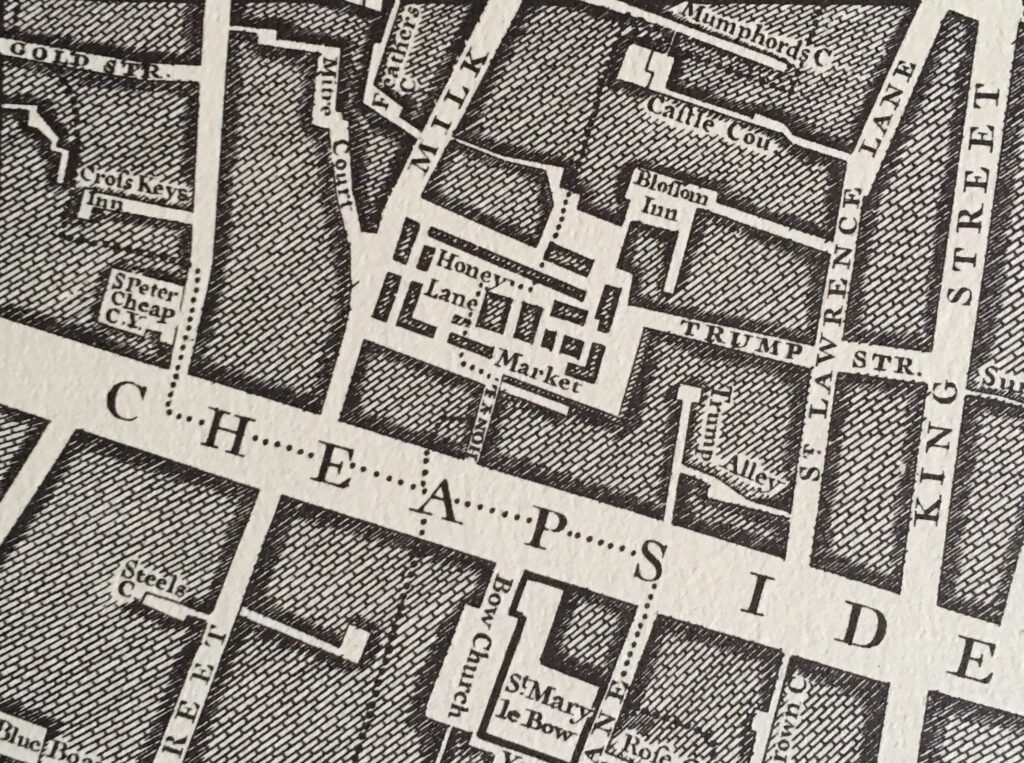

Whitecross Street dates back to at least the 13th century, with the first written records of the street as Wytecroychestrate.

The name of the street seems to derive from a white cross located in the street, which seems to be connected to the Abbot of Ramsey who had a house between Whitecross and Redcross Streets (Redcross Street is another old street that was just to the west of Whitecross Street and took its name from another cross in the street. Redcross Street was lost during the construction of the Barbican).

Strype, writing in 1720 includes the following reference to the street: “In this street was a white cross and near it was built an arch of stone under which ran a course of water down to the Moor which is now called Moorfields. Which being too narrow for the free course of water, and so an annoyance to the inhabitants, the twelve men presented it to an inquisition of the Kings Justices, and they presented the Abbot of Ramsey and the Prior of St Trinity, whose predecessors six years past has built a certain stone arch at Whyte Croyse, which arch the aforesaid Abbot and Prior, and their successors ought to maintain and repair.”

Writing in 1756, William Maitland described Whitecross Street as “a place well built and inhabited. It begins in Fore Street and runs northward into Old Street, which is of a great length. But the part within the Ward goes but a little beyond Beech Lane, where the City posts are set up, as they are in Grub Street and in Golden Lane, being the circuits of the Freedom. The street is inhabited by considerable traders and dealers in various branches.”

The Ward that Maitland refers to is Cripplegate Ward and the City posts were the boundary markers showing the extent of the City. The section of the street that was in Cripplegate is now that renamed Silk Street, along with the section under the Barbican.

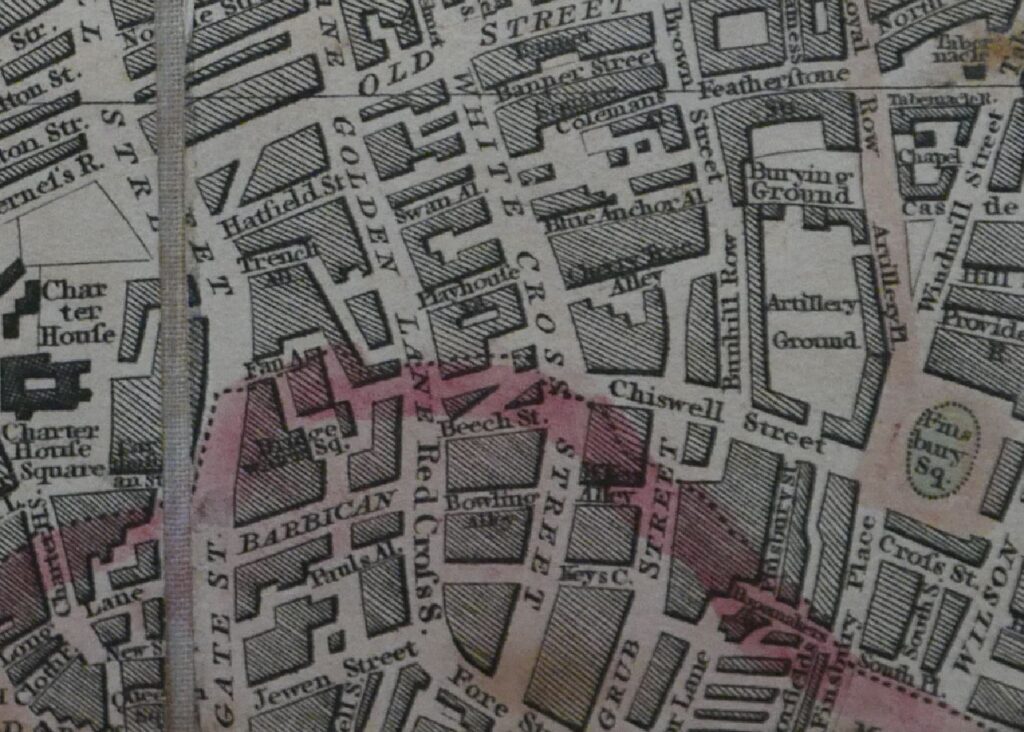

The City boundary can be seen in the following extract from Smith’s 1816 New Plan of London, where the boundary is the dotted line and pink highlighting. The boundary can be seen cutting across Whitecross Street at the junction of Chiswell and Beech Streets.

Today, there are still “considerable traders and dealers” in Whitecross Street, and the street is also a centre for public art that can be found covering many of the walls along the street. The entrance to Whitecross Street from Old Street:

The blue plaque was put up by English Hedonists, and is to Priss Fotheringham, who “Lived here and was ranked the second best whore in the city”.

Priss was mentioned in the collection of pamphlets under the name of “The Wandering Whore” by John Garfield, published between 1660 and 1661, where, in a contrived conversation between two sex workers (probably invented by the author), the activity which seems to have brought Priss fame and some wealth is described “Priss stood upon her head with naked breech and belly whilst four Cully-Rumpers chuck’t in sixteen Half-crowns into her Comodity”.

Whitecross Street is mentioned a number of times in the pamphlets, including the lists of “Common Whores, Night-walkers, Pick-pockets, Wanders and Shop-Lifters and Whippers”, where for example “Mrs Smith, a Bricklayers wife in Whitecross” is mentioned, along with “Mrs Savage in Whitecross-street, who broke her husband’s head with a marrow-bone, and had liked to have kill’d him with it”.

The street was much improved by 1800, when it was described as “A good street, and has among the buildings, the Peacock brew house, the Green Yard, where strayed cattle are pounded, and where the Lord Mayor’s state coach is kept.”

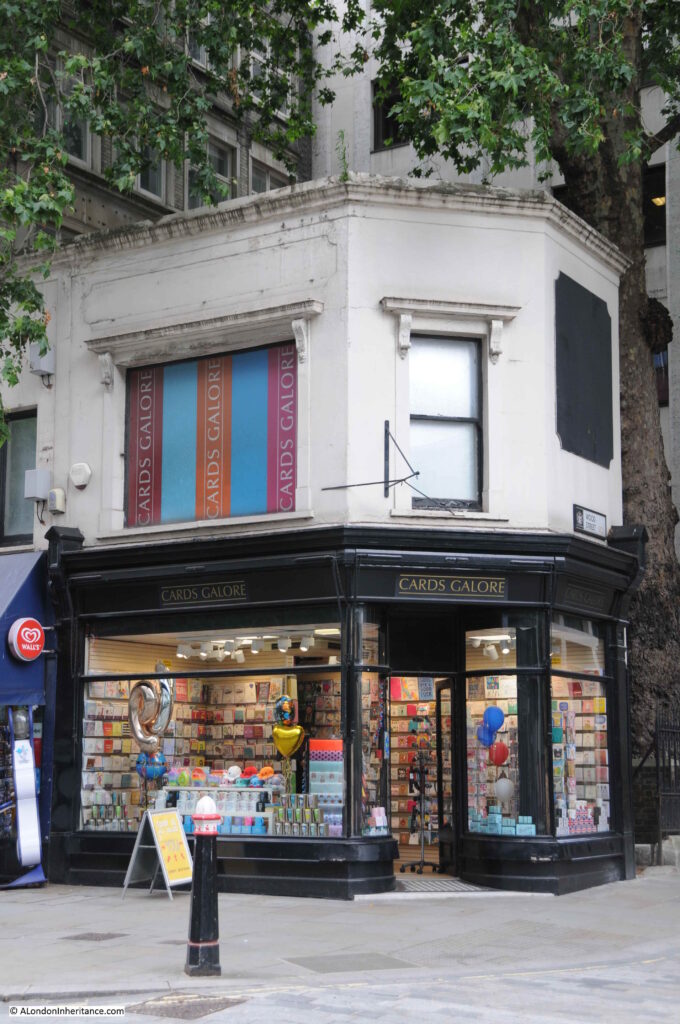

Walking down the street, and this is the building that helped with identification of my father’s photo:

The following building appears further down the street in my father’s photos, so although not an 18th or 19th century brick terrace, the building is pre-war. I obviously read too many archaeology websites and books, as every time I see the café on the corner, Museum of London Archeology is the first thing I think of.

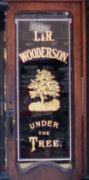

The Whitecross Tap:

The Whitecross Tap is a relatively recent name, dating from 2018, however a pub has been on the site since the 18th century.

Looking south along Whitecross Street at the junction with Banner Street:

The street has a very diverse mix of architectural styles, which make the street interesting. Different heights, materials, windows and function all jostle for prominence.

Street art is visible along much of the street:

The art along the street is the result of the Whitecross Street Party and the Rise of the Nonconformists exhibition, an annual event that has been taking place for the last 11 or 12 years, taking place over a weekend when there are multiple events in the street, and street artists can be watched as they create new works.

A pub that has been converted to a coffee shop. This was the Green Man pub:

More art on the side of the Peabody Estate between Whitecross Street and Cahill Street. Most of the estate was built in the 1880s.

Whitecross Street has had a market for very many years. It was once a street market that sold the everyday needs of those living in the area; a typical London street market, however like the majority of other London street markets, today it mainly caters for the lunchtime needs of those who work in the area.

It was a very different place not that many years ago, and the change to the food market we see today has been relatively recent. A newspaper report from February 1871 provides a graphic description of the market as it was;

“Out-dinning the din of the Whitecross-street Sunday morning market, the roar of leather lunged costermongers and barrowmen, the deafening eloquence of the clashing knives and steel of opposition butchers, the shrill cries of women who have potherbs, and children’s toys and second-hand shoes and boots on sale. The wrathful high pitched voice of the street preacher at this corner of an alley, unable to make himself heard amid the laughter created by a quack dealer in sarsaparilla at the other corner, over all these conflicting noises the sound of a bell was heard distinctly – not the measured chiming of a church bell, nor the preemptory clatter of a factory bell, but a fitful and uncertain ringing, now loud and heavy like a fire bell. A gentlemen in the baked potato interest, however, to whom I applied for information on the subject, ruthlessly stripped the bell of everything in the shape of romance. it is the Costers Mission Bell, said he.”

The market seems to have started around 1830. In the Clerkenwell News dated the 2nd November 1865, there is a report of a Vestry meeting, where the work of a recently appointed “street keeper” who was responsible for the upkeep and cleanliness of Whitecross Street and the adjacent alleys, courts and streets was discussed. The concern was the work was too much, as “Amongst other things he was required to be in attendance during the day in Whitecross-street as a market”.

There was consideration given to removing the market, however the Vestry Clerk stated “As to the market in Whitecross-street, stalls had been allowed to be there for upwards of thirty years, and could not very easily be removed now”.

No idea if there is a similar role as a “street keeper” today, however the market is very busy each lunch time.

With almost any combination of street food you could want:

With queues forming at many of the stalls:

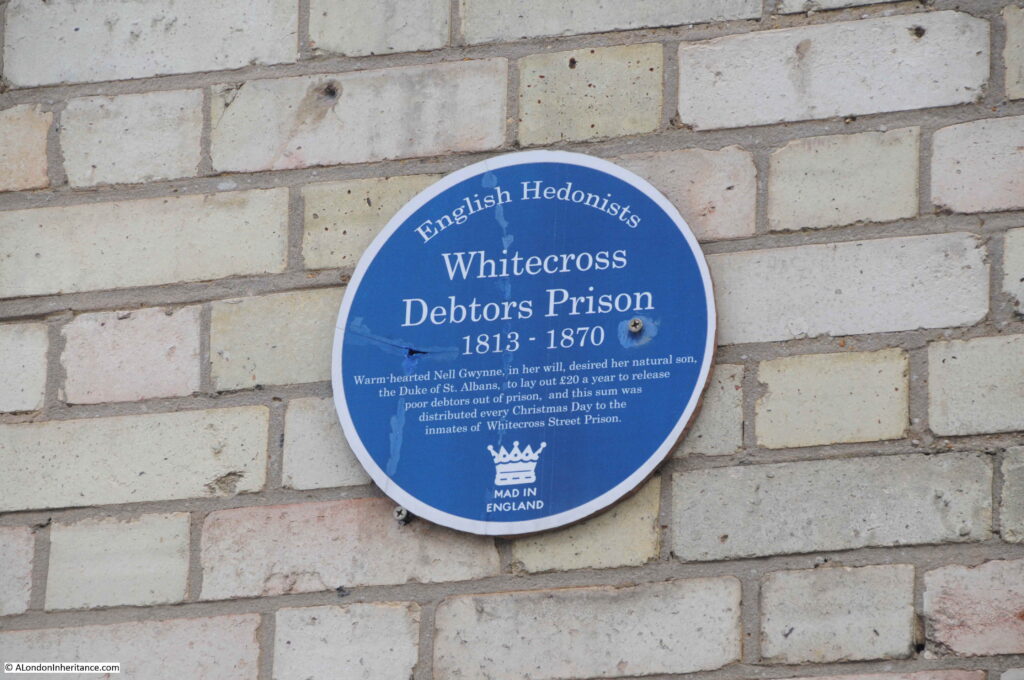

There is a plaque on the corner of Whitecross Street and Dufferin Street:

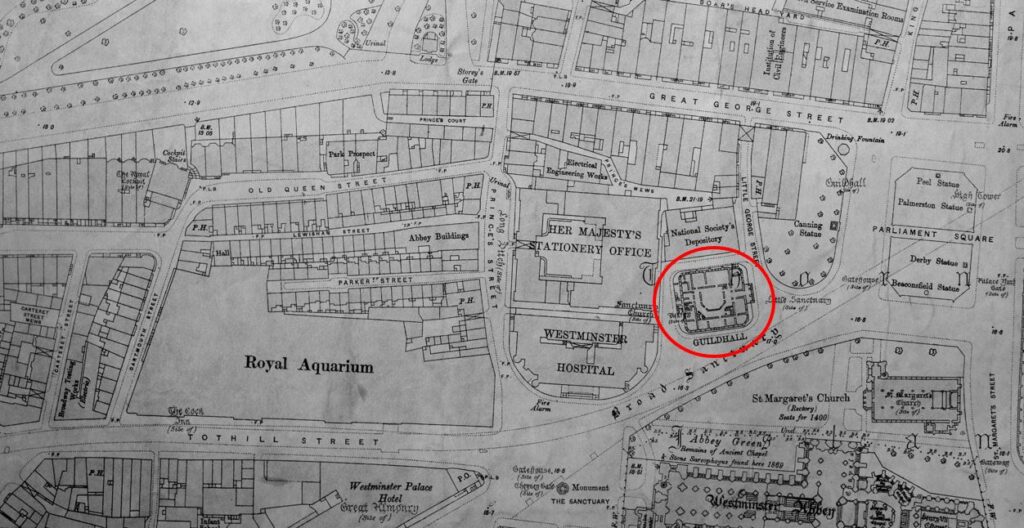

The plaque is a long way from the actual location of the prison, which was at the southern end of Whitecross Street, between Whitecross, Redcross and Fore Streets. The following extract from the 1847 edition of Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London shows the location of the prison, circled in red.

Today, the site of the prison is underneath the Barbican. In the following photo, I am looking across to the Barbican Centre from near the tower of St Giles. Gilbert House is on the right. The Whitecross Street prison was on the site of the building with white panels on the lower floors. Redcross Street ran to the left of the photo. Whitecross Street ran under / in front of Gilbert House.

The prison was a debtors prison. Prior to Whitecross, if you were in debt and could not pay these off, then you could find yourself in a prison along with those being tried or convicted of a criminal offences ranging from petty crimes to murder.

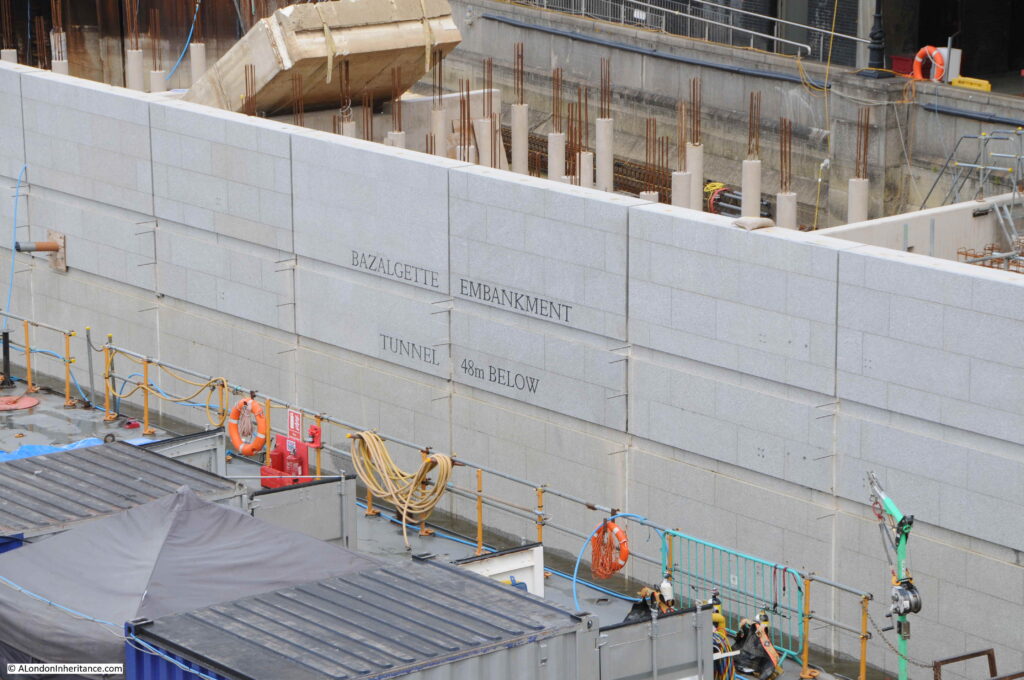

In the early years of the 19th century there was a campaign to separate debtors from criminals, and the Whitecross Street prison was the result, being built between 1813 and 1815.

Although a prison full of debtors could be just as difficult to manage as a normal prison, as this article from the London Commercial Chronicle on the 17th September, 1816 reports:

“RIOT IN WHITECROSS-STREET PRISON. On Saturday evening another riot broke out in this prison among the confined debtors. it appears that a prisoner had committed some offence, for which the other prisoners thought proper to pump him. Mr. Kirby, the keeper, being informed of the transaction, found out two of the principals, and insisted upon locking them up, which was accordingly done. The rest of the prisoners resisted, and at length broke out into open rebellion, refusing to be locked up in their wards. Finding them continue refractory, a reinforcement of officers was sent for; and the City Marshal, accompanied by a posse of constables, speedily arrived, when the rioters submitted, and tranquility was restored.”

However, by 1834, the prison seems to have established a community feel. The Monthly Magazine reported the views “From an Inmate of Whitecross prison”:

“I have been a wanderer over a large portion of the globe during the last fifteen years, and have had various opportunities of seeing and studying men of many nations. In earlier life I saw much of France and Frenchmen; from them I have received the greatest kindness – and great hospitality. I have dwelt with Germans and Dutchmen, and the most agreeable recollections are connected with my sojourn among them. After years in official life, thousands of miles from ‘fair England’ circumstances threw me into the midst of Swedes, Danes and Spaniards, all of whom have given me opportunities of lending their kindness and generosity; but I have never in my life saw so perfect a display of the best feelings of our nature, as are in daily action and continual exercise under this roof. The society here appears one large brotherhood.

Association in sorrow softens and ameliorates the heart; selfishness is, perhaps, less known in this place than in any other ‘haunt of society’. The poorest captive shares with real pleasure his meagre meal with his less fortunate neighbour; kindness of heart shines in brightest splendour”.

Whitecross Street prison closed in 1870. The number of debtors had been declining, and an Act of Parliament had come into force abolishing imprisonment for debt. A report from the 8th January 1870 illustrates the unusual scenes when the prison was closed:

“SCENE AT WHITECROSS STREET PRISON: Release of the Prisoners – On Saturday, just after twelve, being the 1st of January, the day on which the new act to abolish imprisonment for debt came into force, Mr. Constable, the keeper of Whitecross-street Prison, gave as many as 94 prisoners leave to go out of prison. Of that number 63 prisoners availed themselves of the offer, and 31 asked to remain in the place for another day. Only 41 remain in custody on county court commitments, penalties, and orders for payment by magistrates. About eleven o’clock, a person named Barnacles, who had been twenty-seven years a prisoner, on an order from the Court of Admiralty, was told by Mr. Constable to leave the place, and he went out staring about him after his long imprisonment. Mr. Constable has acted in a humane manner, instead of prolonging the imprisonment of the parties until applications were made to a judge at chambers.”

One can only imagine Barnacles confusion as he left prison. He had been in the Whitecross prison for half of the prison’s existence.

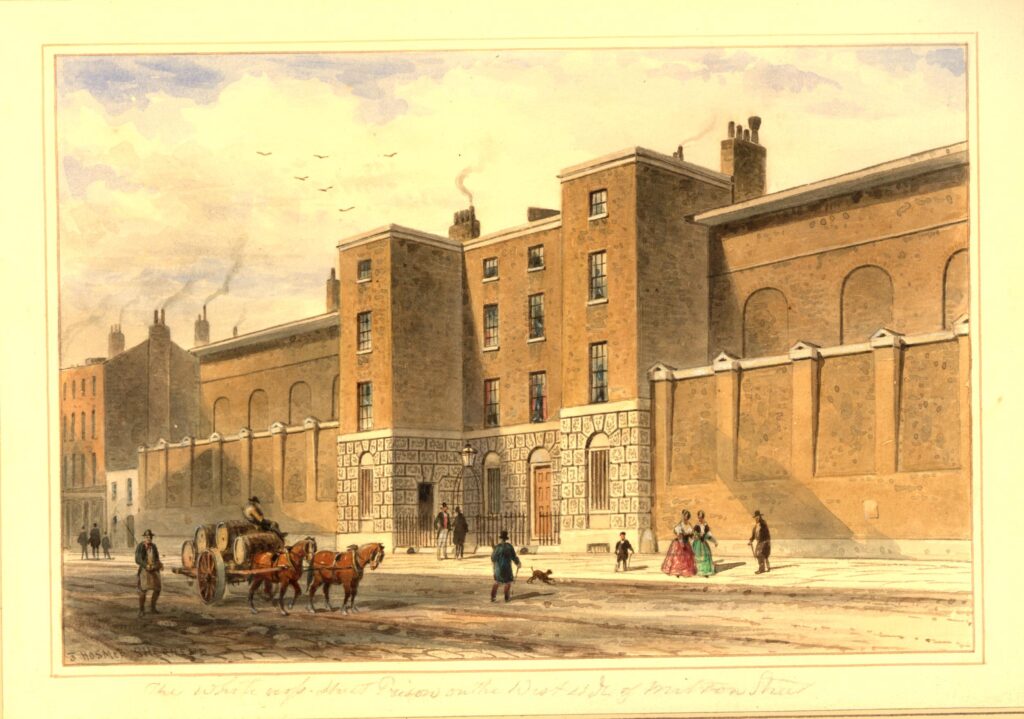

Whitecross Street Prison for Debtors as it appeared in 1850 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The Two Brewers pub on the corner of Whitecross Street and Fortune Street. A pub has been here since the mid 18th century.

More street art:

The market occupies the northern section of Whitecross Street, leaving the southern section free. The Barbican can be seen at the end of the view, which now covers the lower section of the original Whitecross Street.

Much of Whitecross Street suffered severe damage during the bombing of the early 1940s. Whilst a number of the original brick terrace houses did survive, others have been significantly repaired and some have been rebuilt to look similar to the original building.

At other places along the street, completely new blocks have been constructed over bomb damaged areas, including this large block on the south-eastern side of the street, which includes a Waitrose on the ground floor behind the covered market area.

However the pleasure of Whitecross Street is that there are many of the buildings and small shops remaining, similar to those photographed by my father in 1953.

Whitecross Street is today much shorter than the pre-war street. As with so many streets in the area between Old Street and London Wall, post war development of the Barbican and Golden Lane estates have obliterated so many historic streets.

The side streets also have much to tell of the history of the area, and it is a fascinating area to explore. Although best not to follow Barnacles example of a long period of imprisonment, his approach on leaving Whitecross Street prison of “staring about” is a good approach when wandering the area.