In 2017, I photographed the area to the west of Euston Station, with a focus on St. James’s Gardens, as this area was about to become the construction site for the expanded Euston Station, for the London terminus of HS2, a high speed railway that would run to Birmingham with branches to Manchester and the east Midlands.

Each year since 2017, I have made a return visit to the area around Euston Station, intending to photograph what was there before demolition, then the construction phase and finally the new Euston Station.

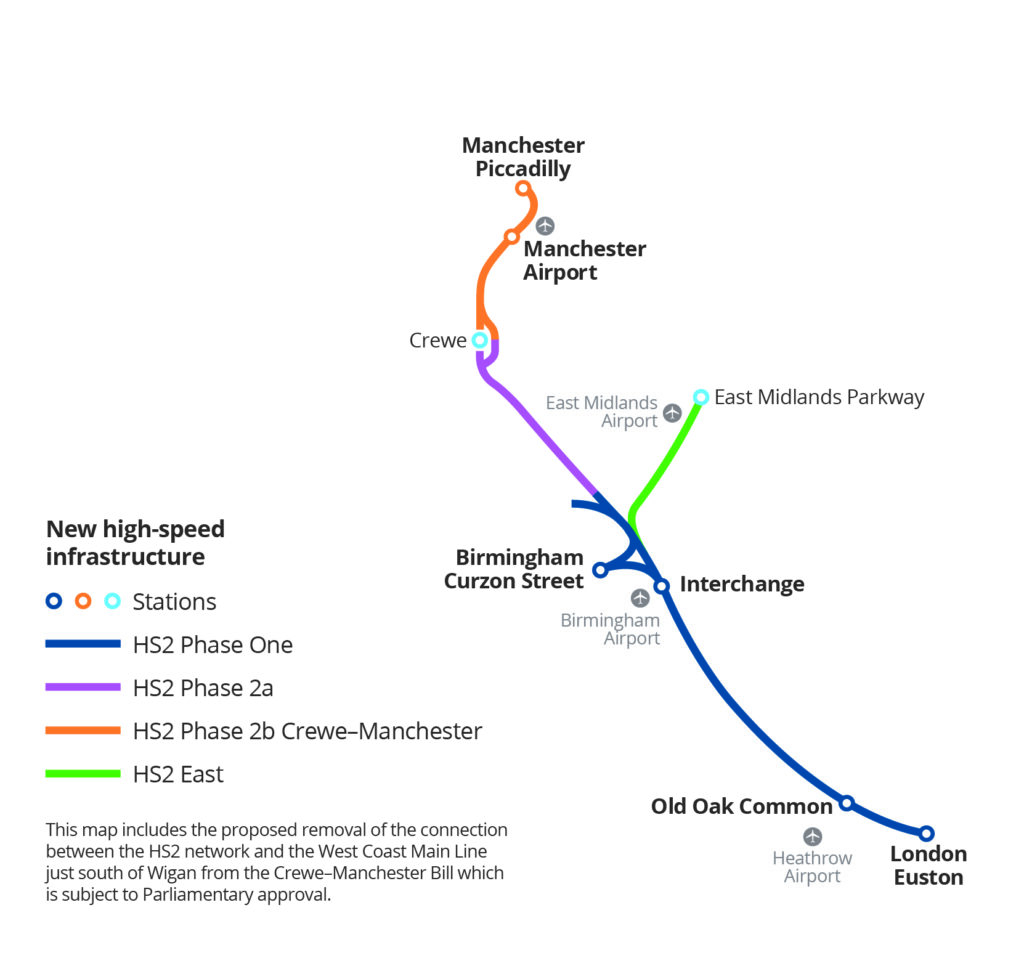

In recent years, the future of HS2 has been in doubt, and a couple of months ago, the Government announced that the northern sections would be dropped and that the London section between Old Oak Common and Euston Station would be paused.

In the latest HS2 6-monthly report to Parliament – November 2023, it was stated that delivery remains on track for “Old Oak Common in west London and Birmingham Curzon Street by 2029 to 2033”. There was no date given for completion of the section from Old Oak Common to Euston.

There is a list of all my previous HS2 posts at the end of this post, and after anticipating seeing a new station as the final post in this series, I now wonder whether I will ever get to see a new HS2 station at a redeveloped Euston.

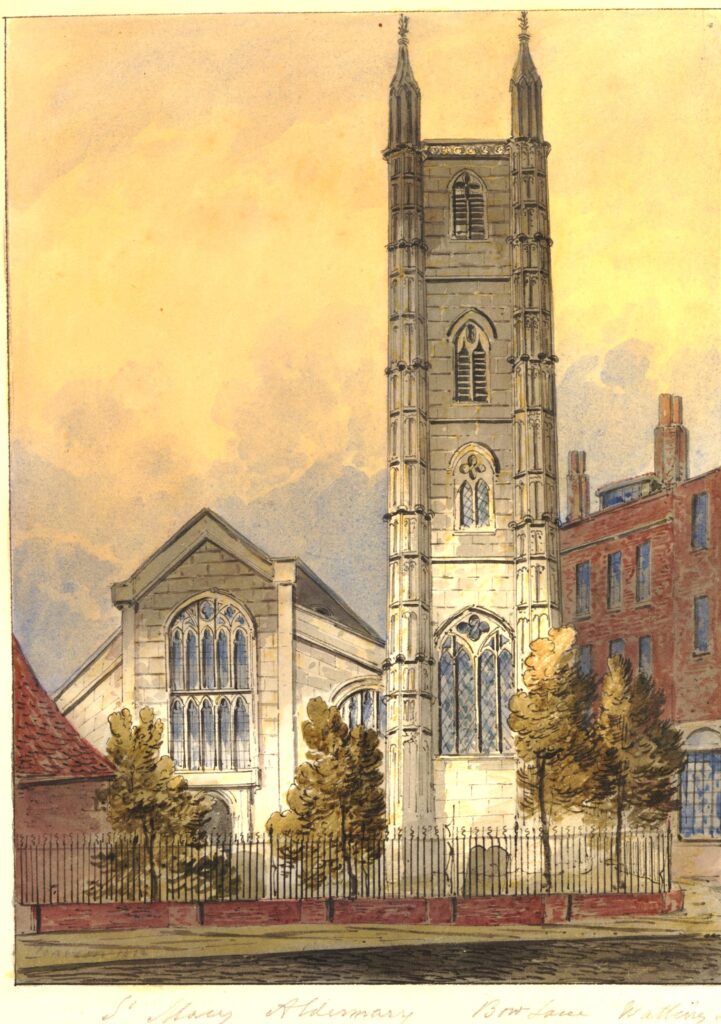

The following map from the Media section of the HS2 website shows the route as it was still planned in 2022:

As well as pausing construction of the section from Old Oak Common to Euston, the November report to Parliament stats that “we will not proceed with Phase 2a, 2b or HS2 East”.

Much of the construction area is hidden behind panels, many of which have artwork and advertising that tells the story of what HS2 will bring to Euston, and the wider benefits of the project. Much of this now looks rather hollow and out of date, and includes the new Euston Station:

And as well as “building you a better Euston”, the following poster still states that HS2 will be “Connecting eight out of ten of Britain’s largest cities”, and will “More than double the number of train seats out of Euston in peak hours”:

And that improvements to the existing station will provide a “Bigger, better concourse, 100s of new seats, wider platform ramps”.

Extension of HS2 from Old Oak Common to Euston has been “paused”, and the November report to Parliament states that:

“We are going to scale back the project at Euston and adopt a new development led approach to the Euston Quarter which will deliver a station that works, is affordable and can be open and running trains as soon as possible. We will not provide design features we do not need and will instead deliver a 6-platform station which can accommodate the trains we will run to Birmingham and onwards and which best supports regeneration of the local area. In this way we will attract private funding and unlock the wider land development opportunities the new station offers, while radically reducing its costs to the taxpayer.”

But the most scary part of the new plans for Euston is this sentence in the November report:

“At Euston, we will appoint a development company, separate from HS2 Ltd, to manage the delivery of this project. We will also take on the lessons of success stories such as Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms, which secured £9 billion of private sector investment and thousands of homes.”

Whilst economically, Nine Elms has been considered a success in bringing in considerable (mainly overseas) investment to develop the area, the Nine Elms development seems to have resulted in the random placement of individually designed tower blocks, without any apparent cohesive design for the area. The towers look as if they have been randomly dropped from the sky, with a height and density to maximise profit rather than to add character and improve a key part of London.

Is this the future for Euston? A station hiding underneath another vision of Nine Elms, delivering enough cash from developers to complete the section from Old Oak Common to Euston along with the new station, but with a focus on the needs of developers, rather than a new the design and build of a new station that could have served as the London terminus of a growing railway to the north of the country.

In the following map, I have added a red line to show the area which had been cleared for the new station, and the tracks leaving the station to head to Old Oak Common (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

HS2 have a couple of photos in the Media section of their website which shows the scale of the site. The following is looking at the site from the north:

And the following view is looking north, with Euston Station to the right:

Both of the above photos are available to download from the Construction section of the HS2 media Gallery at this link.

I suspect that the main problem that HS2 has had is the name – High Speed 2.

The slightly shorter journey time from London cannot really justify the expense of the project, and the additional speed will only really benefit journeys much further north than Birmingham.

The main benefit that HS2 provides is extra capacity on existing rail lines, such as the West Coast Main Line (WCML).

Transferring high speed trains from the existing WCML onto HS2 would have released a significant amount of extra capacity which could have been used for freight, additional passenger train services between many of the places on the WCML route, as well as increasing the number of high speed trains.

However, calling the project Extra Capacity 1, or EC1 does not sound as exciting as HS2, although it would have been a better description of the real benefits.

I started my 2023 walk on a weekday, when hopefully it would be clear how much work was still underway. My route started in Clarkson Row, just to the west of Mornington Crescent, as here you can just about see over the wall, across the existing tracks, to where new tracks will be run as the railway heads from Euston to Old Oak Common:

Heading along Hampstead Road, and this is the view along the street, back towards Mornington Crescent. The main entrance to the site to the west of Hampstead Road is here:

There was still work underway, however according to HS2 press releases, what is happening now around Euston is “enabling work” rather than construction works, and there were utility works on the street, so I assume this means minor, low cost works which may make the project easier to get underway if and when it restarts.

One of the entrances to the main Euston site:

Look back along the Hampstead Road:

This is the main entrance from Hampstead Road to the main site around Euston Station:

There appeared to be very little happening, and the only vehicle that was running through the site was a road sweeper.

There is no sign of any elements of a new station, and the appearance of the site was much the same as last year. Parts of the site which were open last year have now been fenced off, so the site appears more enclosed than a year ago, but again, not much happening within the site.

There are three places where there is a change to last year, the first is the National Temperance Garden, described as “a temporary green space for all to enjoy”. It has been built on the site of the old National Temperance Hospital, and this is the view of the garden from Hampstead Road:

The large structure behind the gardens are offices and have been there for the last few years. The fencing between the gardens and Hampstead Road are standard HS2 Euston green security fencing and surround places on the site where there are no large panels.

Inside the gardens, which apparently has been “specially designed to be moved and re-used in the local area when the site closes”:

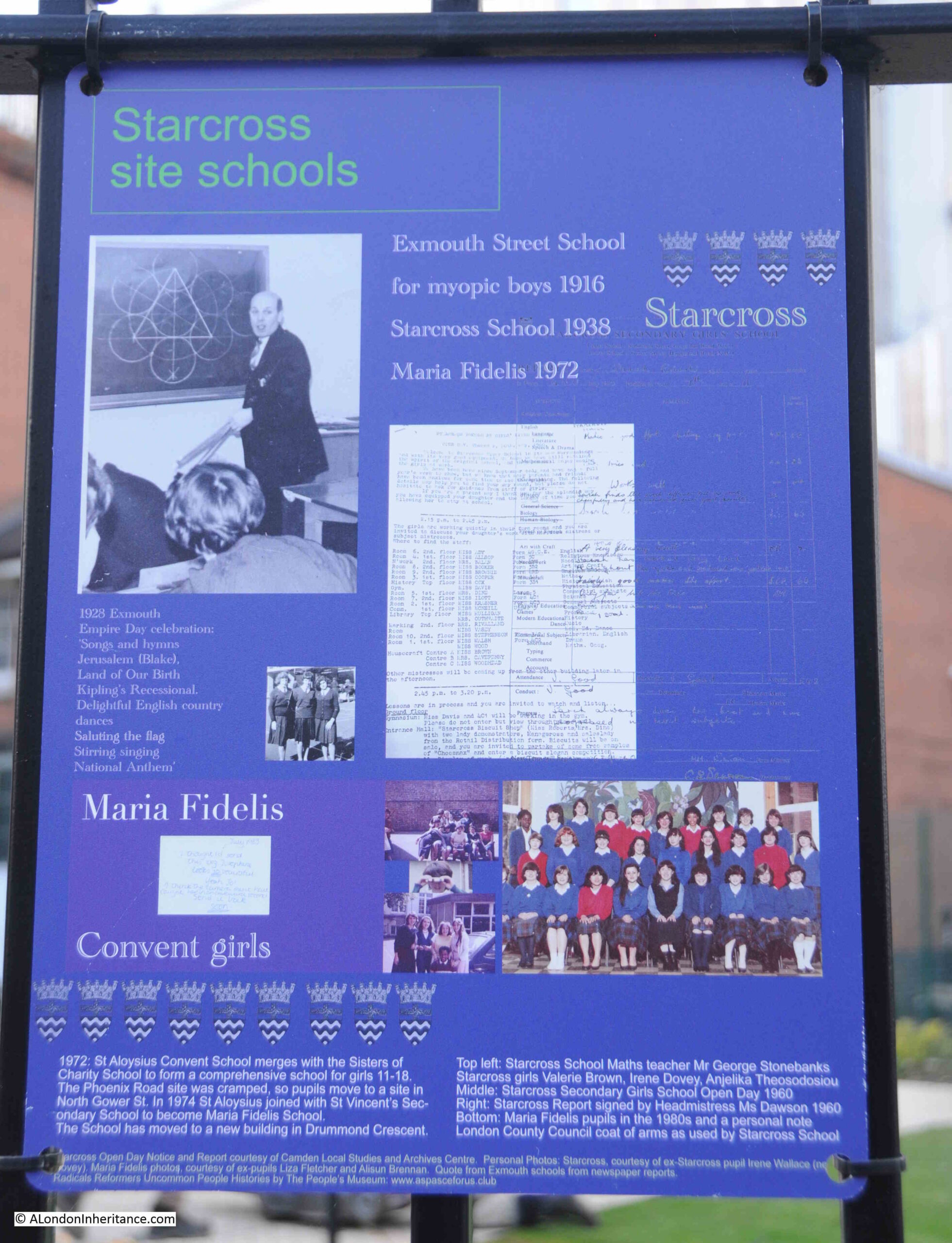

These buildings were home to the Maria Fidelis School:

To free up the school site, HS2 have built a new school between Drummond Crescent and Phoenix Road, and the site in Starcross Street is now closed.

The school and a large new building behind the school are a new “Euston Skills Centre”, set-up to provide training to local people and thereby providing the number of trained workers that such a large project requires.

The Euston Skills Centre was handed over to Camden Council on the 20th of November, however given that work within Camden has now been paused it will be interesting to see what Camden Council does with the facility. Hopefully there are still plenty of training opportunities for Camden locals to work on the project from Old Oak Common northwards.

Between the skills centre and Starcross Street is the second of the places where there has been a tangible change, compared to last year.

This is another temporary open space, in the form of Starcross Yard:

The theme for Starcross Yard is “echoes of place”, and within the space there are physical reminders of places from a surprisingly wide area, not just the HS2 construction site, or Euston.

To highlight these, there are information panels along the railings which tell of the “uncommon histories of people and space”.

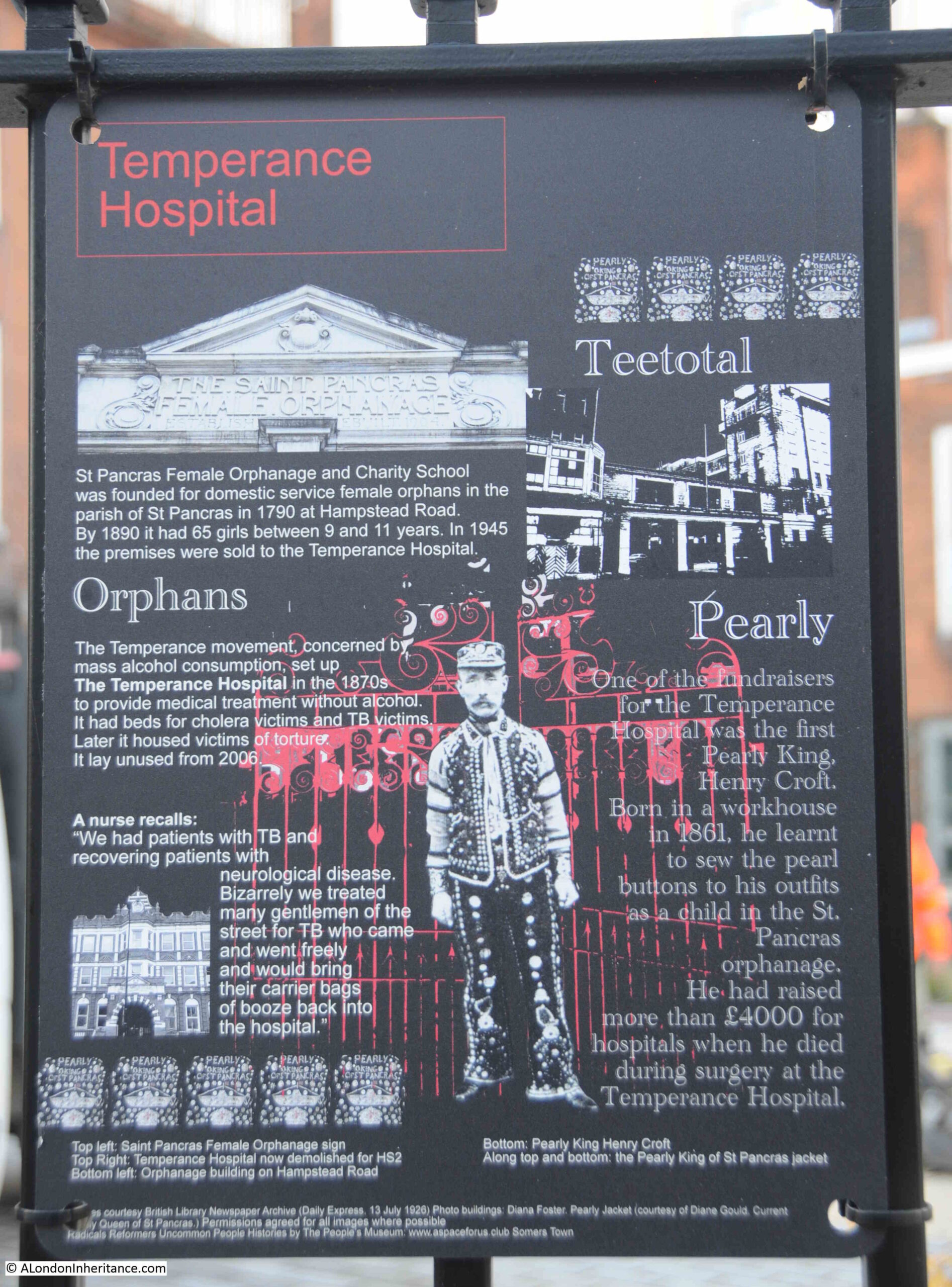

The first is the Temperance Hospital, which was demolished as part of the clearance of the HS2 construction site:

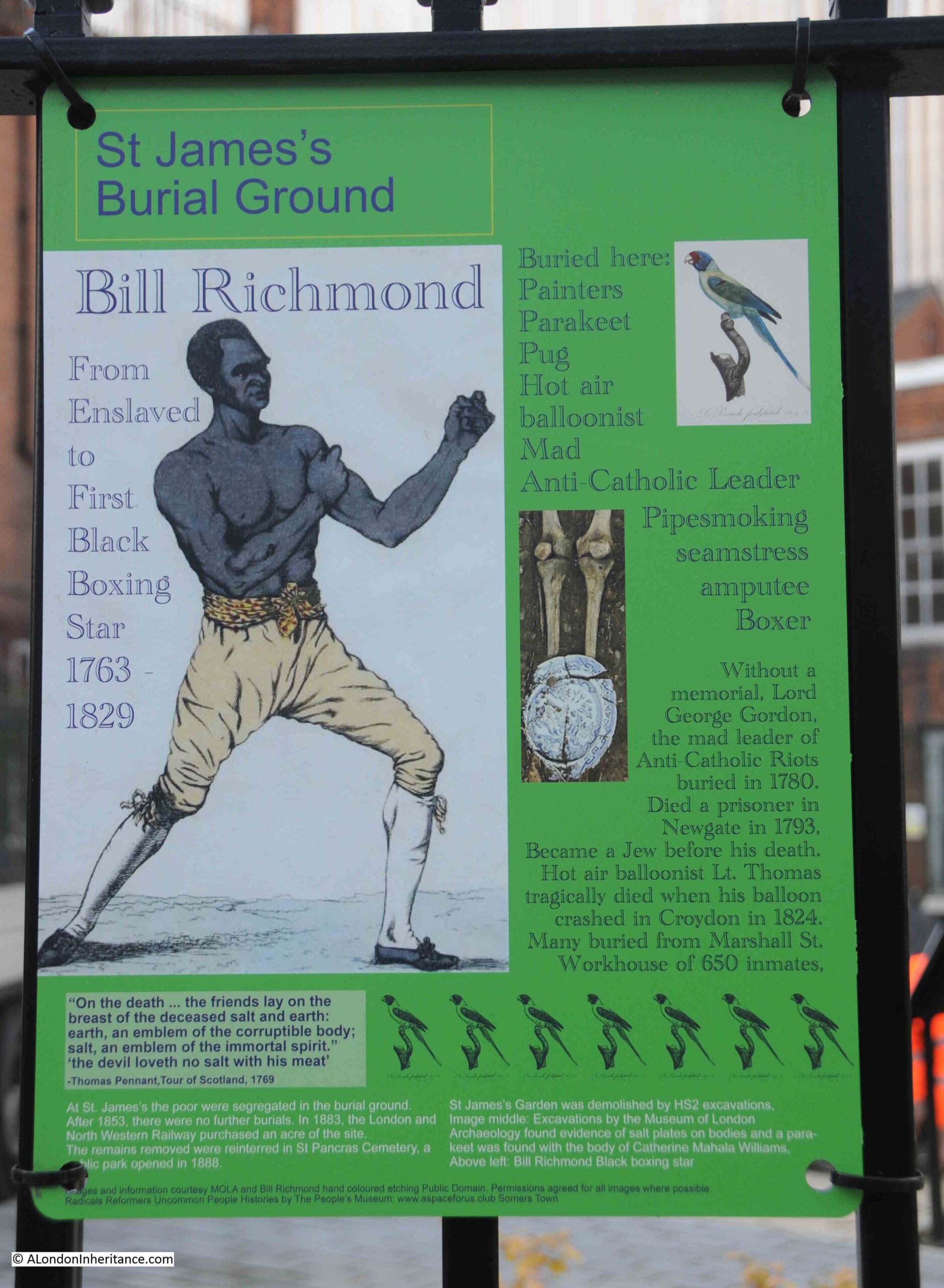

The second covers the St. James’s Burial Ground, which again was cleared as part of HS2 site clearances. The panel highlights the boxer Bill Richmond who was buried at St. James’s Burial Ground, and a number of others buried are also named, as well as many from the workhouse:

Railings from the old burial ground now form part of Starcross Yard.

The above two panels refer to places that have become part of the HS2 construction site. The rest of the panels cover people and places that are further away, and not part of HS2.

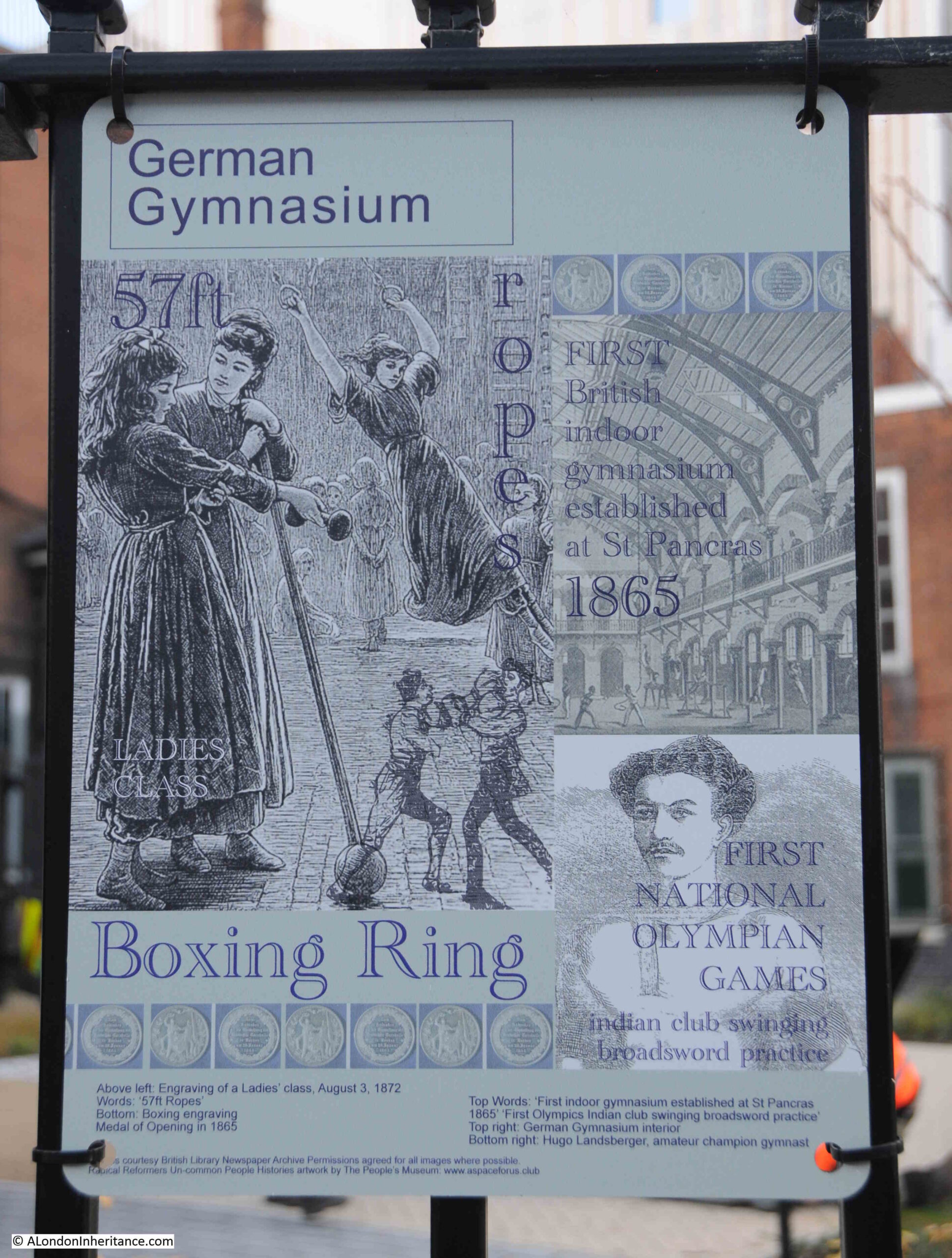

The first of these is the German Gymnasium which today can be found by the southern entrance to Pancras Square, between St. Pancras and King’s Cross Stations:

Poles from the German Gymnasium can now be found at Starcross Yard.

Next up is Cumberland Market:

Cumberland Market was a short distance to the west of Euston Station, at the southern end of the Regents Park Basin, a small dock area off the Regents Canal.

My father grew up next to the Regents Park Basin, and I wrote about the area in this post. Starcross Yard has cobbles from Cumberland Market.

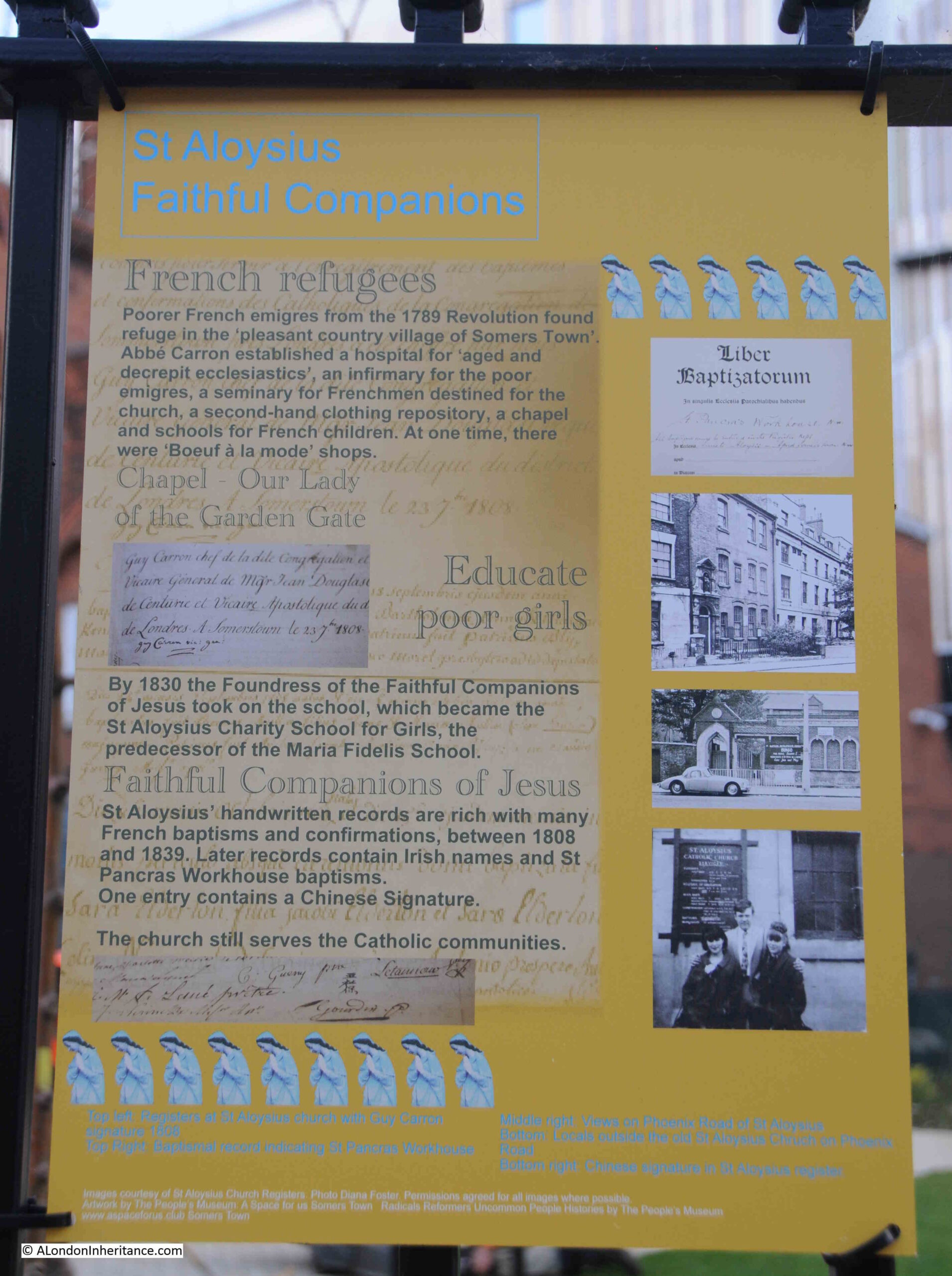

Next is St. Aloysius, a Somers Town Catholic Church:

The church is still functioning, although a mid 1960s rebuild, rather than the buildings shown on the panel. The church can be found to the east of Euston station, in Eversholt Street.

And the final panel covers the local schools, including the Maria Fidelis school, which is the large brick building beside Starcross Yard:

I rather like what they have done with Starcross Yard. Too often when large areas of London are redeveloped, there is nothing left to indicate anything about the people and places that once had a connection to the place.

Starcross Yard is temporary, and I hope whatever comes next retains this approach to the areas history.

Meanwhile, at the end of Starcross Street, the Exmouth Arms are still open:

Next to the Exmouth Arms is another of the site entrances, guarded by a rather bored security person:

At the end of Starcross Street is Cobourg Street, although the road element of the street is now boarded off, with only the footpath remaining.

Cobourg Street crosses Drummond Street, and last year you could walk along this far stretch of Cobourg Street, but during my 2023 visit, the footpath was being fenced off:

It seems to be a result of the “pause” in work of HS2 into Euston, that the whole site seems to be getting more enclosed and secure. I assume if you have a large area of open land sitting idle, you do not want the risk of anyone getting in.

This is the view back along Cobourg Street from Drummond Street towards the Exmouth Arms:

Where Drummond Street once ran all the way to the edge of Euston Station, it now stops at the junction with Cobourg Street, and continues on as a walkway, with the HS2 construction site on either side.

This is the view along the walkway, looking up towards Drummond Street:

And from the same location, looking towards Euston Station:

And back towards Drummond Street:

At the corner of where Drummond Street once met Melton Street is the original Euston station of the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (I wrote about a visit to the station and tunnels in this post):

To the left of the underground station is another large area of cleared space, this was the area once bounded by Melton Street, Drummond Street, Euston Street and Cobourg Street, and was where the Bree Louise pub was to be found:

The following view is from the same position as the above photo, and is looking along where Melton Street ran into Cardington Street. It was a short distance along Cardington Street that St. James’s Gardens could be found. The tree is the only reminder of the trees that once lined part of the street and across the gardens.

The view along what was Melton Street, with a walkway into Euston Station up the ramp to the left:

The walkway along what was Melton Street:

There is a small stub of Melton Street left, where it meets Euston Road, and again has a very quiet entrance to the HS2 construction site:

I then walked along Euston Road to find the third place where there is any tangible sign of a change. At the eastern side of the station is Eversholt Street, and in front of the station, and the bus stops, between Eversholt Street and Euston Road, one of the open spaces alongside Euston Road has been redeveloped:

The area is still secured by standard HS2 Euston green mesh fencing, but through it there appears to be a new taxi drop of point. It all looks finished, but no indication of when it will be opening:

Then a walk to the open space in front of the station:

With a view in the opposite direction showing the office blocks between Euston Station and Euston Road:

Returning to Melton Street, where there is a ramp leading to a walkway into Euston Station, this is the view, with a large open construction site behind the panels on the right:

If you walk into Euston Station, up to the first floor area where there is a pub and food outlets, at the western end of this space there are stairs back down to ground level, and from here there is a view over the construction space in front of the station, with Melton Street to the right, and taxi ranks alongside Euston Road:

Not much happening in this large area:

The station concourse:

That was the HS2 Euston construction site in 2023. Very little change compared to a year ago, with only two small gardens and a taxi drop off point the only external signs of change.

There were not that many construction workers around, and the perimeter of the site seems to be getting more secure, as if it is closing up for a long period.

HS2 seems to be a love / hate project, and whatever your individual views on the project, it does not give a good impression of the country when we seem unable to build major infrastructure projects such as HS2.

There is an interesting article on the London reconnections website, comparing the costs of infrastructure projects in the UK and other, comparable countries, and it is remarkable just how much extra, projects in this country are to build compared to others.

There are many complex reasons for this. Planning processes, funding complexity, objections to projects, long decision making, changes to decisions etc. all add to cost.

Although the Old Oak Common to Euston section has been paused, there will still be cost, at the very minimum the construction sites will need security, and I suspect it will take very many years before sufficient private finance is found to complete the project.

London Mayors and Government Ministers of all parties seem to like the phrase that “London is open for business”, a phrase which I find rather meaningless, but seems to translate as the city is open for anyone to purchase London’s assets, and this will probably be the way for Euston with offshore investment building up a new Nine Elms above a very slimmed down station.

Apart from the Silvertown Tunnel, HS2 is the only other major public transport infrastructure project in London.

Crossrail 2 has been “paused” since October 2020, and I doubt there will be anything for some decades to come.

Sorry to be so depressing on your Sunday morning.

I stayed taking a few more photos as it got dark, and as I left the station, the new information board in the outside concourse mirrored my thoughts at the time about the future of Euston’s development, with almost every train being delayed:

My visits to the Euston HS2 construction site for the past six years are covered in the following posts:

I then went back in 2019 as demolition started.

And in June 2021 I went back for another walk around the edge of the construction site.

Last year’s 2022 walk around the site is here.

I suspect the site will be much the same when I visit again later in 2024.