When I started this blog, four years ago, I thought I knew London reasonably well – the last four years have taught me how little I really know.

As well as walking in London, over the last four years I have been reading a lot more London books. It is a wide field, books have been written about London for centuries, as well as what seems like a continuous flow of new books. There are also books about almost every aspect of London that you could imagine.

I find books through a number of routes, browsing both new and second hand bookshops and online, finding books as a direct result of something I have found on a walk, and through recommendations I have received as a result of some of my posts.

For this last post of the weekend, here are the London books that I have read over the past year, books that have taught me so much about the city.

I will start off with:

This – Is London

This book came from a second hand book shop in Alton, Hampshire. Browsing the shelves, I came across a book with the word London in the title. It looked interesting, was £4 so I took a chance and purchased.

This – Is London is by Stuart Hibberd who was a BBC Announcer in the early days of the BBC, when an announcer was the person who introduced all the programmes, read the news, looked after guests, and generally appears to have done almost everything (apart from the technical work) needed to get BBC programmes on air.

The book takes the form of a narrative diary, starting in 1924 through to 1949, a period which included so many events of historical importance, as well as the development of the BBC from the very early days through to the post war status of an established national and international broadcaster.

The book is very much of its time – written by a BBC announcer, when a Vice-Admiral was a BBC Controller. It feels that to read the book you need to be dressed in a dinner jacket, pipe in one hand and glass of whisky on the side table, however it is written by someone who was there at the time and includes some fascinating insights into how radio programmes were put on air (I did not know that the BBC had a studio in a warehouse on the Southbank in the 1930s) and some interesting stories of working in London.

The following is an example, and will be familiar to anyone who has experienced a last minute platform change at one of London’s stations, however I bet Southern Railways would not do this for you now, even if you did work for the BBC:

“On Saturday, 9th November 1935, after a long day at Broadcasting House, ending at midnight, with the help of a waiting taxi I managed to get to Charing Cross station about a minute before my train was due to leave at 12:10 a.m.; and I walked past the barrier on to Platform 4, above which was displayed on a board marked ‘Orpington and Chislehurst’. The train was not standing at the platform, but, as it was Saturday night, when trains are sometimes a little late, I thought nothing of that. When at 12.13 I went up to the ticket-collector and asked him what had happened to the Chislehurst train, he answered with surprise, ‘It has left from No. 2 platform on time’. This rather shook me, as of course I knew it to be the last train, and I also knew that the Orpington and Chislehurst board had been over the entrance to Platform 4 when I passed the barrier. There were five or six other passengers there bound for Orpington, who now came up and, in no uncertain tone, corroborated what I had said. As they raised their voices, along came an inspector. They were furious with him, saying, ‘How are we to get home?’, ‘We’ve all been fooled’, ‘I’ll report you’. and that sort of thing.

Realising that this would get us nowhere, and knowing that there was a train from London Bridge to Bromley at 12.45, and that I could if necessary walk the three and a half miles from there, I got into a train then leaving for London Bridge.

While in this train I did some quick thinking, and remembered that London Bridge was the Divisional Headquarters of the railway. Arriving there I went straight to the Inspector’s office, and told him what had happened, beginning in a rather causal tone of voice, ‘Nice game at Charing Cross tonight Inspector. Your men put up the Orpington train-board on No. 4, and then ran the train out of No. 2; and as it was the last train, I look like being stranded, unless I walk home from Bromley.’ He was incredulous, and said, ‘You must have made a mistake.’ No I assured him, I had made no mistake, and what is more, I warned him that he had better be prepared for the other angry passengers dropping in at any minute, who would not relish the walk from Bromley to Orpington at one o’clock in the morning. At this he opened his eyes and began to look worried, but was obviously reluctant to take any action to put things right. I paused for a moment or two; then decided to play my trump card. ‘It isn’t as if I had been out enjoying myself at the theatre or something,’ I said. ‘I’m B.B.C., and have been broadcasting on and off all afternoon and evening, and am pretty tired.’ The three magic letters, B.B.C. did the trick, and he at once decided to ring up the night controller on duty. At that moment, as I had warned him, a bunch of angry passengers from Charing Cross burst in to demand retribution. I explained that I had forestalled them, and that the Inspector was now talking to the night controller about it. We had to wait ten minutes or so while he checked up, then he sanctioned a special train, which drew into London Bridge station, just after one o’clock”.

You would not get a special train arranged for you today!

Stuart Hibberd signing autographs at a BBC exhibition – these were the days when a radio announcer was considered a true celebrity.

Again, the book is very much of its time, however as a first hand account of the early days of the BBC in London, This – Is London makes a fascinating read.

The White Rabbit

Last August I wrote a post about Queen Square, it was the location of one of my father’s photos as he had taken a photo of the water pump that can be found in the square. At the northern end of the square is Queen Court, a rather nice brick apartment building that has an entrance on Queen Square and Guilford Street. In the photo below is the Guiford Street entrance (see how money was saved in construction – the cheap bricks in the middle and the expensive bricks where the main facades face onto Queen Square and Guilford Street.)

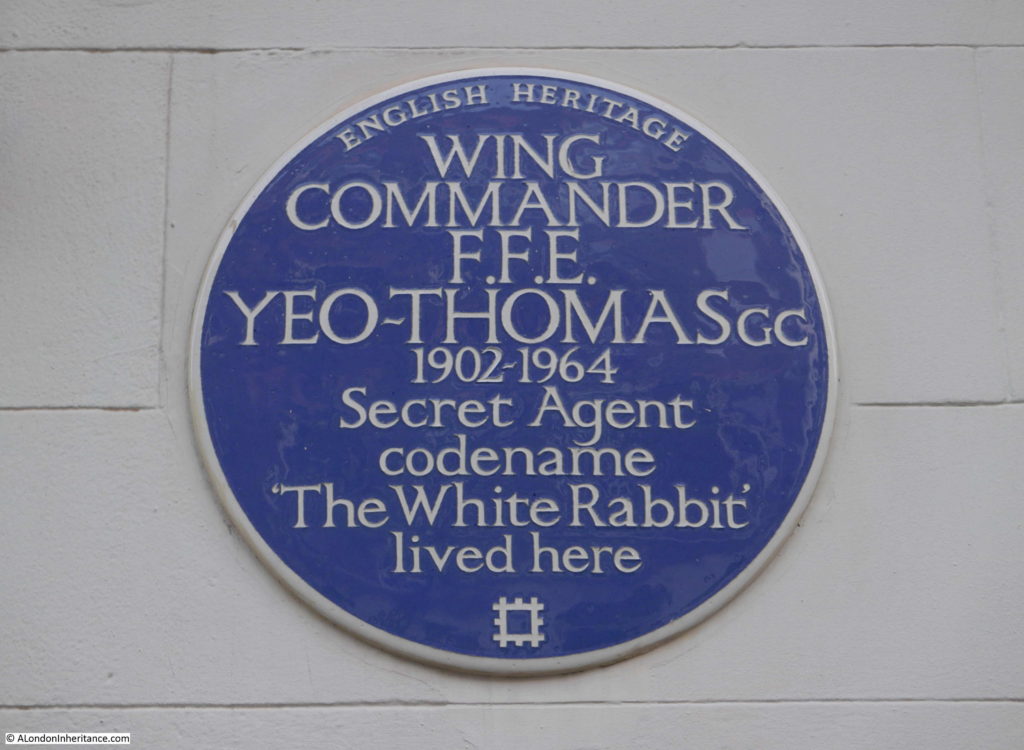

To the right of the door is a blue plaque, to Wing Commander F.F.E. Yeo-Thomas:

Forest Frederic Edward Yeo-Thomas was born in London on the 17th June 1902. At a young age his family moved to France where he became fluent in French as well as English. He served in the First World War, and between the first and second world wars, he worked as a Director of the French fashion house Molyneux.

He returned to Englad at the outbreak of the Scond World War and joined the RAF and transferred into the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1942. His knowledge of France and the French lanquage, as well as his desire to help with the liberation of France made him a natural candidate for becoming a secret agent, working in occupied France,

The connection with Queen Court is as the location of the flat he would share with Barbara Dean after she acquired the flat in 1941. It was from Queen Court that he would leave when he was to be dropped into occupied France to make contact with the resistance, arrange supplies and organisation and report back to the SOE.

I walk past so many blue plaques, but this one demanded more research. I had heard of his code name ‘White Rabbit”, but did not know the full story of his work.

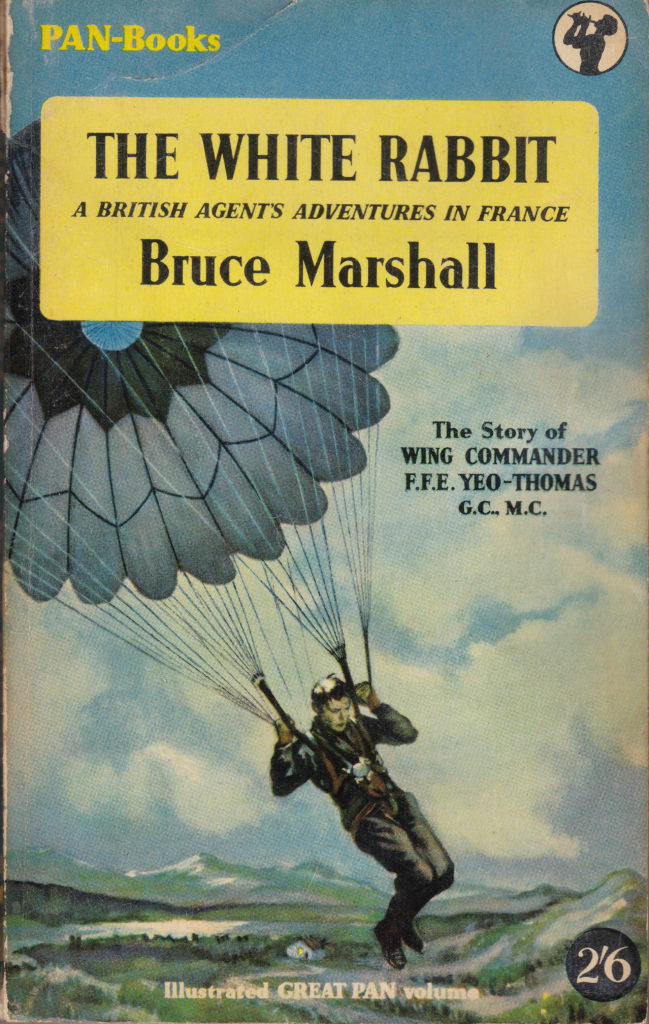

After 10 minutes online I had ordered the following paperback, published in 1954 by Pan Books with the rather dramatic cover illustration:

Although not written by Yeo-Thomas, it was written by his friend Bruce Marshall who had also lived in France and had worked in the Intelligence Services during the war.

Yeo-Thomas had already been dropped twice into occupied France, however in February 1944 he left Queen Court for his final drop into France, one that was to be the most challenging, and one that he was very lucky to eventually return from.

He was captured by the Gestapo during this third trip, interrogated and tourtured and eventually sent to the Buchenwald Concentration Camp along with 36 other prisoners from the allied forces.

The book is a raw account of the inhumanity of a totalitarian regime and should be required reading in order to understand the depths a once civilised society can sink to when others are regarded as sub-human.

The following paragraphs are from the description of Yeo-Thomas’ first days in Buchenwald:

“Guignard also corroborated what Perkins had already told them, adding dismal details of his own. They were, he told them, in the worst camp in Germany. Their chances of survival were practically nil: and if they did not starve to death, they would be worked to death; and if they were not worked to death they would be executed. Every single day more than three hundred prisoners died from starvation or from being beaten by the guards while working in Kommandos. Each Kommando consisted of hundreds of prisoners quarrying stone, dragging logs or clearing out latrines under the supervision of Kapos and Vorarbeiter. But the SS guards were also there and so were their Alsatian hounds, and when enough amusement couldn’t be derived from bludgeoning a man’s brains out there was always the alternative of setting the dogs upon him to tear out his throat.

They soon saw for themselves that these reports were not exaggerated. Walking up and down in the sunlight behind the barbed wire and conversing in makeshift esperanto with the other inmates of the Block, they saw groups of SS men wandering about the camp. They noticed too, that prisoners tried to avoid them and that when they couldn’t they politely removed their forage caps. But this salute did not prevent the guards beating up any prisoner whose appearance attracted their displeasure; and their new companions informed the thirty-seven that anyone attempting to resist this attention was punished either by shooting or strangulation or, if he were lucky, by twenty-five strokes on the small of the back with the handle of a pick axe.

A squat black chimney just beyond the Block was pointed out to them. ‘That’s the crematorium,’ they were told. ‘It’s the surest of all escape routes; most of us will only get out of this camp by coming through that chimney as smoke.”

After Buchenwald, Yeo-Thomas was transerred to other camps as the German lines collasped before he finaly escaped and made his way through to the Americal lines, returning home to Queen Square in 1945.

Afte the war he would help bring several Nazi war criminals to trial, he returned to work in Paris and from 1950 was the French representative of the Federation of British Industries. He died in 1964.

Yeo-Thomas was awarded the George Cross and Military Cross. From France he received the Croix de Guerre and was made a commander of the Legion d’honneur.

The White Rabbit is a remarkable story of a remarkable man, one I only discovered after walking past a blue plaque.

The First Blitz

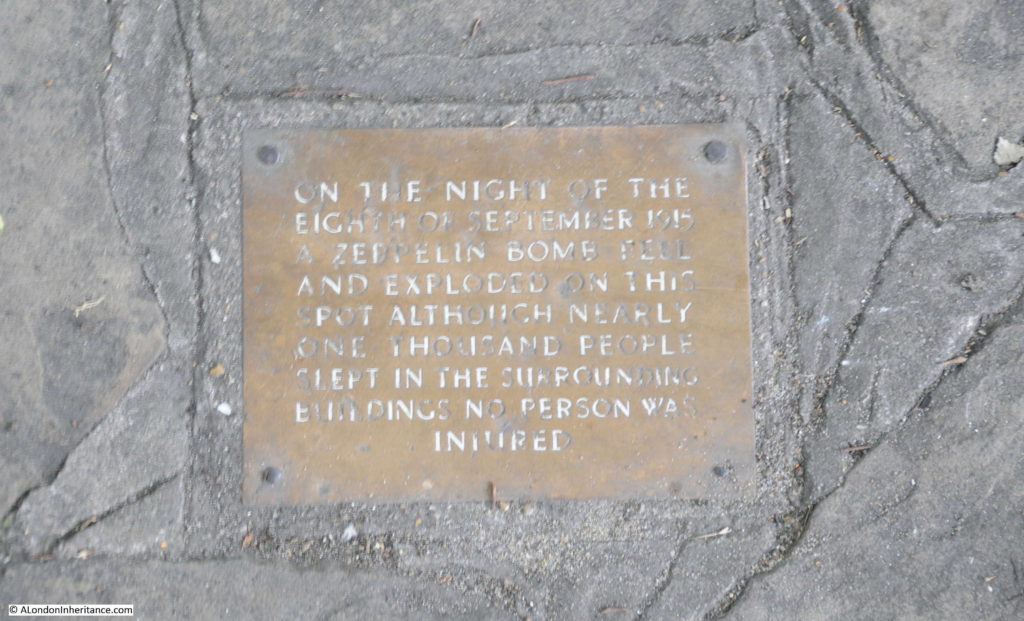

The next book is also a result of my Queen Square post. In the central square, there is a plaque on the ground recording the night when a Zeppelin bombed the square:

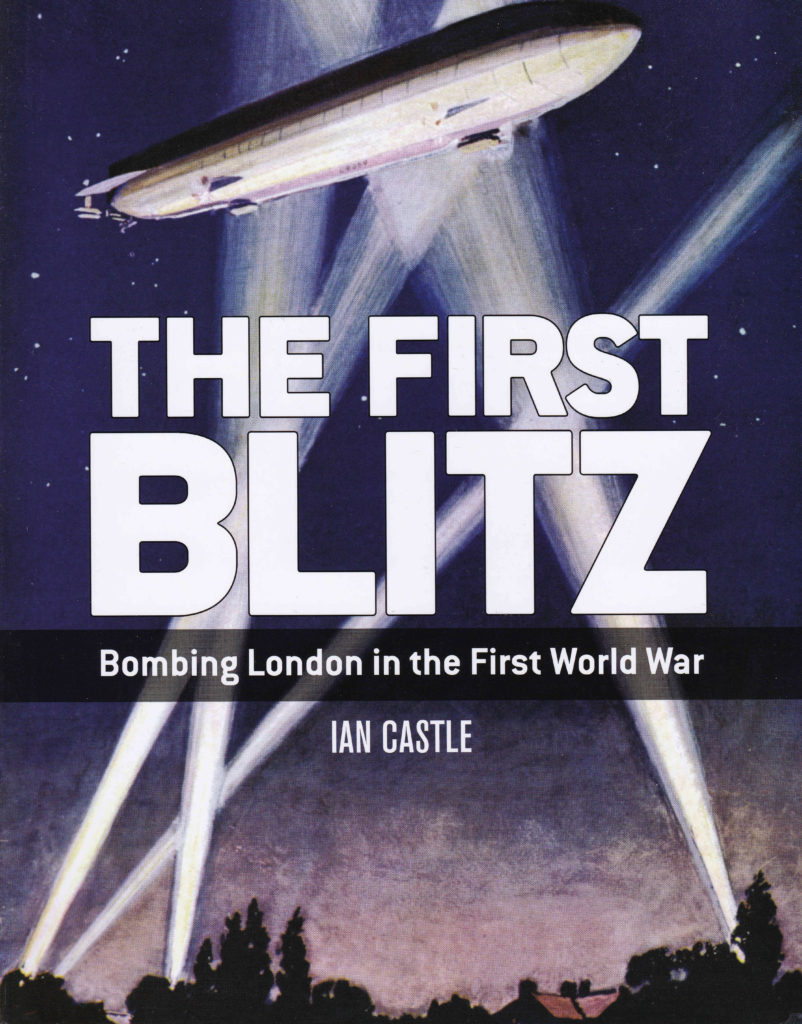

Again, this is a subject I knew a little about, but not in any great detail. In the comments and messages I received after the post, there was one from the author of a book on the Zeppelin attacks on London during the First World War – the long suffering credit card came out and I ordered the book.

The First Blitz by Ian Castle is a very detailed account of the bombing of London during the First World War, covering the background to the raids, the technology used by the attackers and defenders, a detailed account of each raid, richly illustrated with photos and maps showing the route taken by Zeppelins over London and showing the location of where each of their bombs landed across the city.

The book starts when Zeppelin airships were the method for attacking the city and ends with the Whitsun raid on Sunday 19th May 1918 when 38 Gotha aircraft took off to attack London with 19 reaching London. 48 people were killed and 172 injured in this final raid – an indicator of the type of mass attack from the air that would arrive 22 years later.

This Is London

When walking the streets of London, travelling on the Underground or the bus, do you ever wonder about the people around you? Who they are, what are their stories.

London is such a multi-layered construct and there are people all around the city who live and work in their very own confined view of London.

This Is London by Ben Judah is subtitled The Stories You Never Hear. The People You Never See.

The book starts at Victoria Coach Station at 6am in the morning where new arrivals to the city stumble of coaches and buses, and then takes the reader along a journey through London meeting the type of person who are there in the background of the city – office cleaners, builders, beggars, gangs and drug dealers, Filipina maids, the Arab daughters of incredibly rich fathers, witch doctors. The book is a relentless journey through so many of the different sub cultures and people that call London home for just a couple of months or for a lifetime.

In many ways I found the book a concerning read, the poverty, the almost slave like conditions, the lack of opportunity and the almost total isolation of many communities does not give much cause for hope, however it is an important book, a book that will make you look at the people you pass in the city in a new light.

Big Capital

Big Capital by Anna Minton, whilst tacking a very different subject to This Is London, raises a similar set of questions – who is London for, what is London becoming and who owns London.

Big Capital is about housing in London and those who struggle to find a place to live. Big Capital examines how housing has become a financial investment rather than a basic right.

As with This Is London it can be a concerning read, however it is also an important read to understand why there is a housing crisis in London, even though there is a never ending conversion of existing buildings into flats and new tower blocks of flats are constantly rising above the city.

The following extract from Big Capital summarises how housing is moving further into expensive, private renting and (also a theme in This Is London), the poor, slum housing that is growing at the bottom end of the market:

“For the last generation Britain’s economy and culture have been predicated on the ideal of home ownership, fueled by the Conservative vision of a property-owning democracy. But despite the mythology, Britain exceeded the European average of 70 per cent home ownership only in the early noughties. It has now fallen to 64 per cent, the lowest level in thirty years; the last time home ownership was this low was in 1986, when Right to Buy and the deregulation of the mortgage market were sending home ownership upwards. As home ownership falls and social housing is eradicated, expensive private renting is becoming the only option; in 2017 private renting overtook mortgaged home ownership in London. This is a middle class issue now, that people want to talk about, Betsy Dilner, director of Generation Rent, the campaign group for better private renting, told me, although she added: ‘People think we represent this middle-class professional group, but if you can find a way of making the private rented sector work for the most vulnerable people in society then it will work for everyone.’ Today, 11 million people in Britain rent privately in an overlapping series of submarkets ranging from the poor conditions and slum housing at the bottom end to student accommodation, micro ‘pocket living’ flats. apartments for professionals and luxury housing at the top.”

As you walk around London and see the endless building, the advertising hoardings outside new apartment blocks and the new towers rising above the city, Big Capital helps explain how we have reached this point and provides another view of London – it is an important book.

The Boss Of Bethnal Green

The Boss of Bethnal Green by Julian Woodford is genuinely a book that is hard to stop reading once started. It tells the story of Joseph Merceron who grew wealthy through his control of the vestry, the funds destined for the poor, funds that were destined for infrastructure improvements such as the Commission of Sewers, and much else.

The church of St. Matthew’s plays a central role in the story. The church is one that featured in the Architects’ Journal list of sites at risk in 1973 and I visited the church last year. I just wish I had read the book before my visit as walking around the site, knowing more of the remarkable events that happened, makes a site visit so much more interesting.

Joseph Merceron was also buried at the church and his grave is one of the very few remaining, and as Julian Woodford points out, his grave (and that of one of his key partners Peter Renvoize) survived both a late 19th century graveyard clearance and Second World War bombing.

I accidentally included Merceron’s grave in one of my photos of the church – in front of the corner of the church to the right.

The book also covers the politics of the time and how Merceron was able to flourish with a degree of state support, the prison system, the vestry system that was responsible for local governance, magistrates, bankers and all within the context of an ongoing battle between Merceron and a few, determined, opponents.

Whilst Merceron’s story is 200 years old, it is still relevant in providing a warning of how corruption can flourish in local governance without sufficient transparency or external, independent monitoring and audit – a fascinating book.

The Blackest Streets

Although the Old Nichol, an area of slums in Bethnal Green in the latter decades of the 19th century is at the core of The Blackest Streets by Sarah Wise, the books covers a much wider scope.

There are a number of recurring themes in this, and the other books. As with The Boss of Bethnal Green, the failure of the vestry system of local governance is still an issue in the later years of the 19th century, the problems with private renting, subletting and knowing who is really the owner of a property – themes also found in This Is London and Big Capital – indeed it is interesting when reading books about London of the past one to two hundred years, how many issues are much the same today.

The Blackest Streets also brings alive the reminiscences of Arthur Harding, born in 1886 and grew up in the Old Nichol. These were recorded between 1973 and 1979 and provide a first hand record of live in a London slum.

The book covers so much – communists and anarchists, street regulation, Charles Booth, domestic violence and street violence, ownership of property, fear of the workhouse – indeed the breadth and depth of The Darkest Streets provides not just a view of the Old Nichol, but of so much of London life during the last decades of the 19th century.

The Old Nichol would be swept away through one of the Metropolitan Board of Works / London County Council slum clearance initiatives and replaced by the Boundary Estate (I did not know that the central garden, Arnold Circus was named after Arthur Arnold, the head of new LCC Main Drainage Committee).

To say that I learnt a lot from The Blackest Streets is an understatement.

How Greater London Is Governed

Yes, I admit, this is probably taking London reading too far, however I found How Greater London Is Governed by Herbert Morrison in a second hand bookshop in Hay-on-Wye.

Herbert Morrison was a Labour politician and leader of the London County Council (LCC) from 1934 to 1940. The book is an overview of how the LCC governed London and the services that the LCC provides. It is an interesting contrast with the issues of governance in London highlighted in the previous two books, how significant was the improvement by the 1930s.

The book is full of pride in what the LCC has achieved and also the formality required to govern a city of the size and complexity of London.

The book includes a wide range of statistics to illustrate the services provided by the LCC:

- maintenance of 400 miles of sewers

- the provision of 63,600 dwellings with accommodation for 290,000 people (part of an ongoing slum clearance scheme)

- maintains 32 general hospitals, 11 hospitals for the chronic sick and 30 special hospitals

- maintains the London Ambulance Service, answering in 1932, 40,000 calls and conveying 300,000 patients

- maintains 1,150 public elementary schools in which about 600,000 boys and girls are taught

- has spent £17.5 million pounds on street widening

- maintains 97 parks with an area of nine square miles

- maintains the London Fire Brigade with 65 stations and 200 fire appliances

- manages the safety of the public at 800 public buildings

- the Council’s Supplies Department was responsible for the purchase of significant volumes of consumables including an annual purchase of 10,000,000 eggs, 15,000,000 pounds of potatoes, 30,000,000 pints of milk and 19,000,000 million envelopes

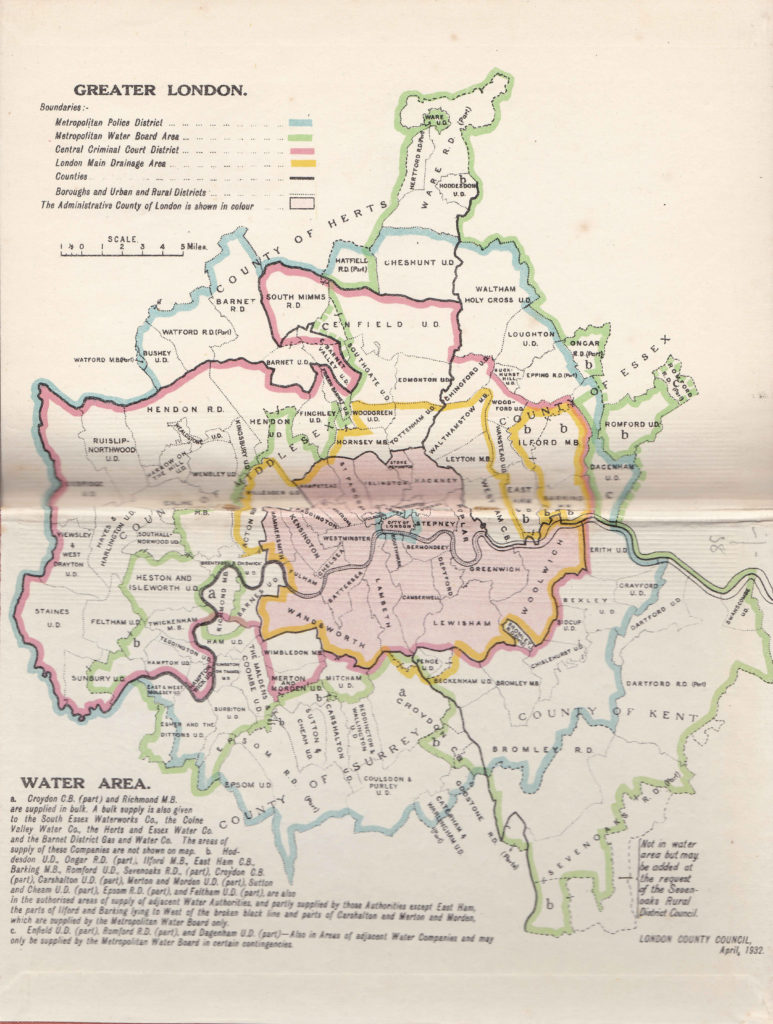

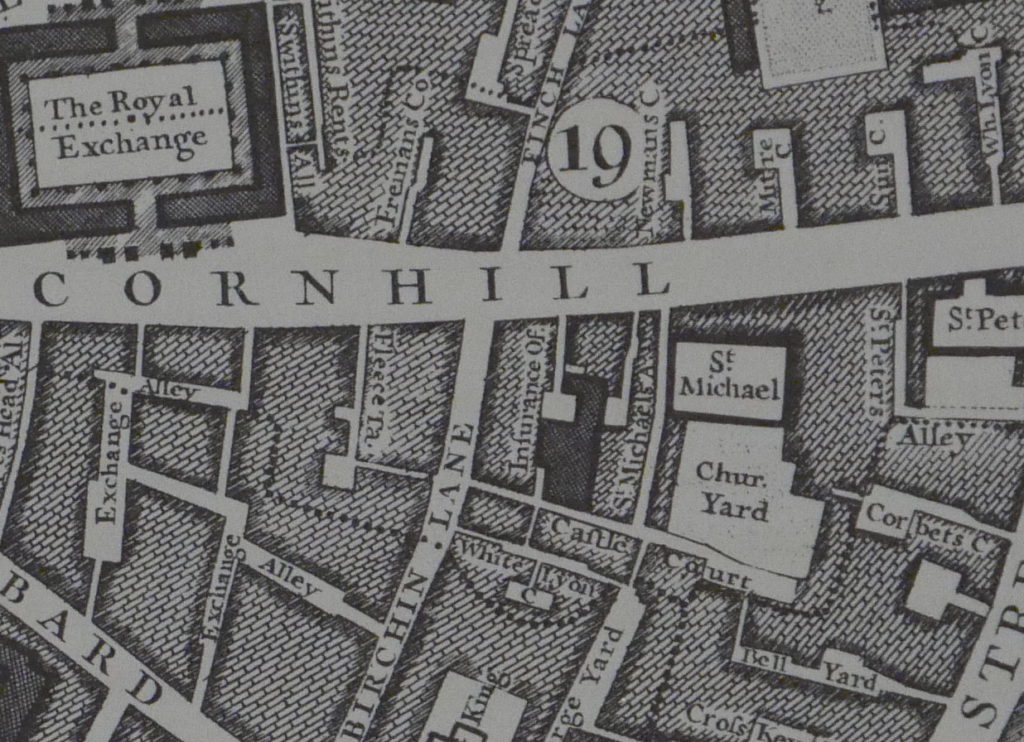

There are also maps to show the complexity of managing a city where there are so many different authorities with different boundaries for their scope of responsibility:

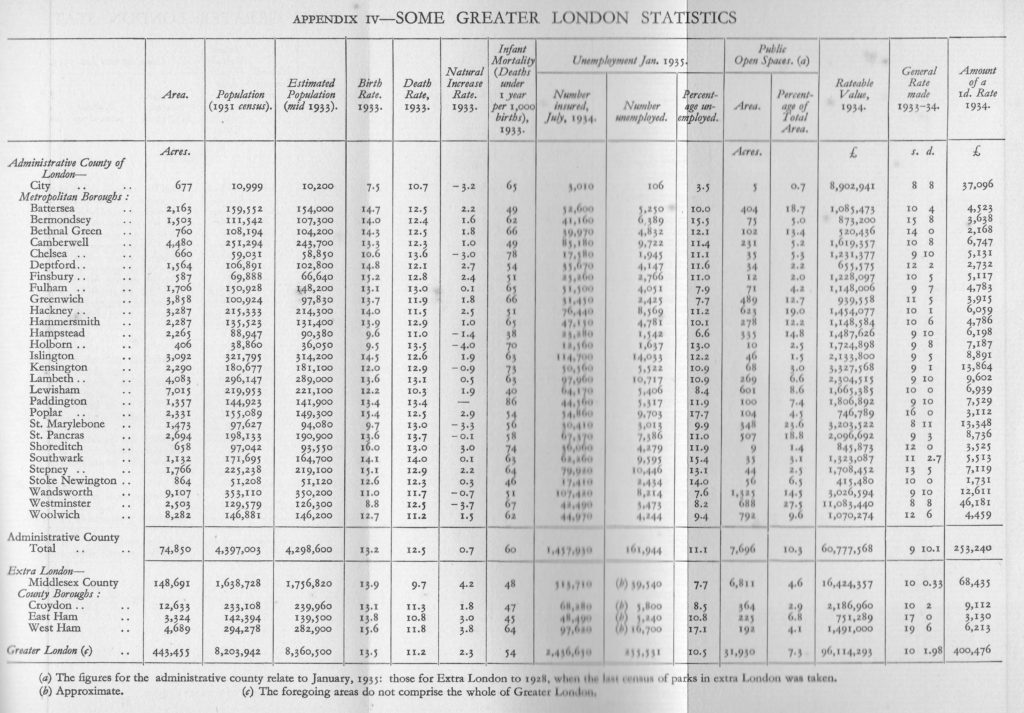

Along with tables on the population, birth and death rates. number unemployed etc.

How London Is Governed provides a snapshot of the city and shows how the governance of such a complex city had evolved from the Metropolitan Board of Works and the Quarter Sessions, and many of the issues of the 19th century as illustrated in the previous two books.

Everything You Know About London Is Wrong

Everything You Know About London Is Wrong by Matt Brown is a wide ranging review of the myths, urban legends and stories that take on the illusion of fact.

Covering topics such as Landmark Lies, Famous Londoners, Popular Culture and Plaques That Got It Wrong, for me reading the book generates the same worry I get when writing every weekly post, that something I thought I knew is just a myth, and that everyone else really knows the true facts.

I am not going to admit which ones i got wrong (mercifully few), but reading Everything You Know About London Is Wrong was fascinating, not just for correcting or confirming my knowledge of the city, but also for the additional background information the book provides for each of the “facts” and stories covered.

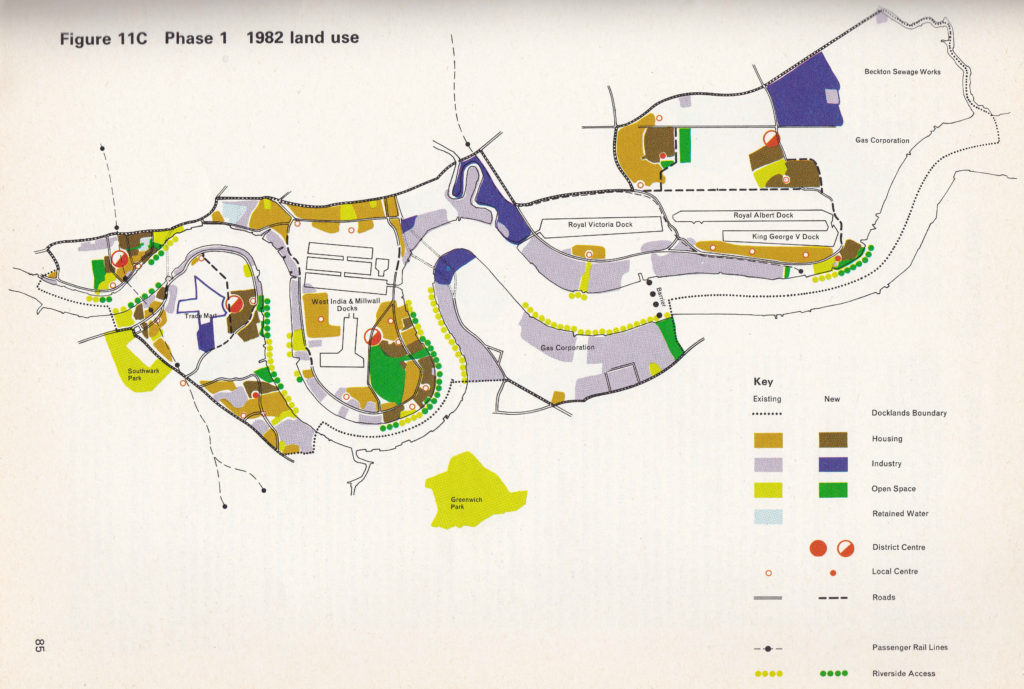

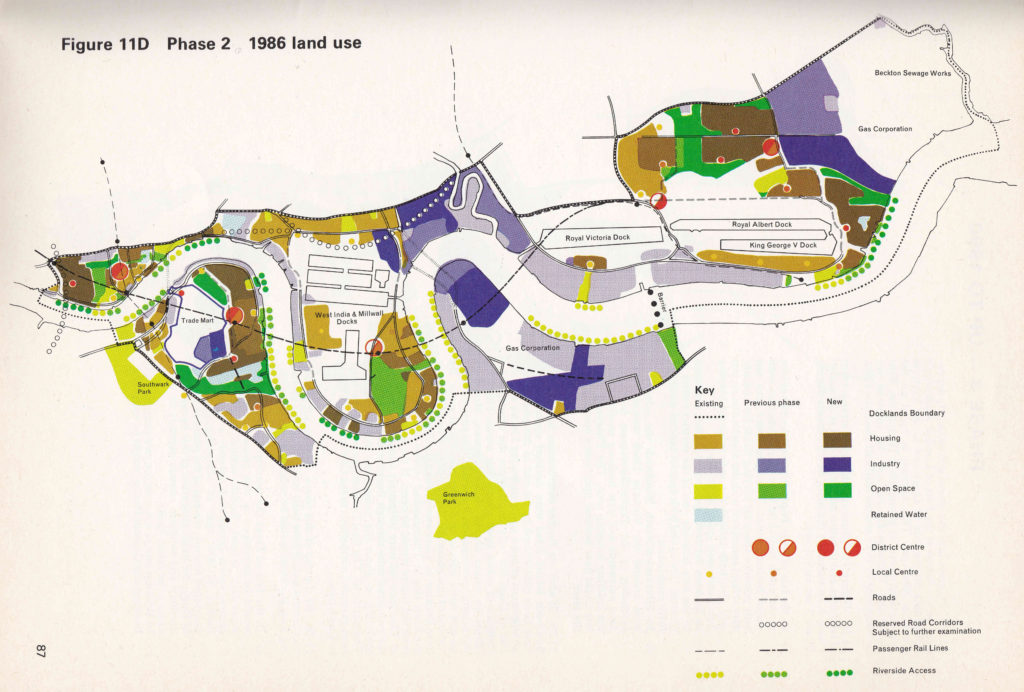

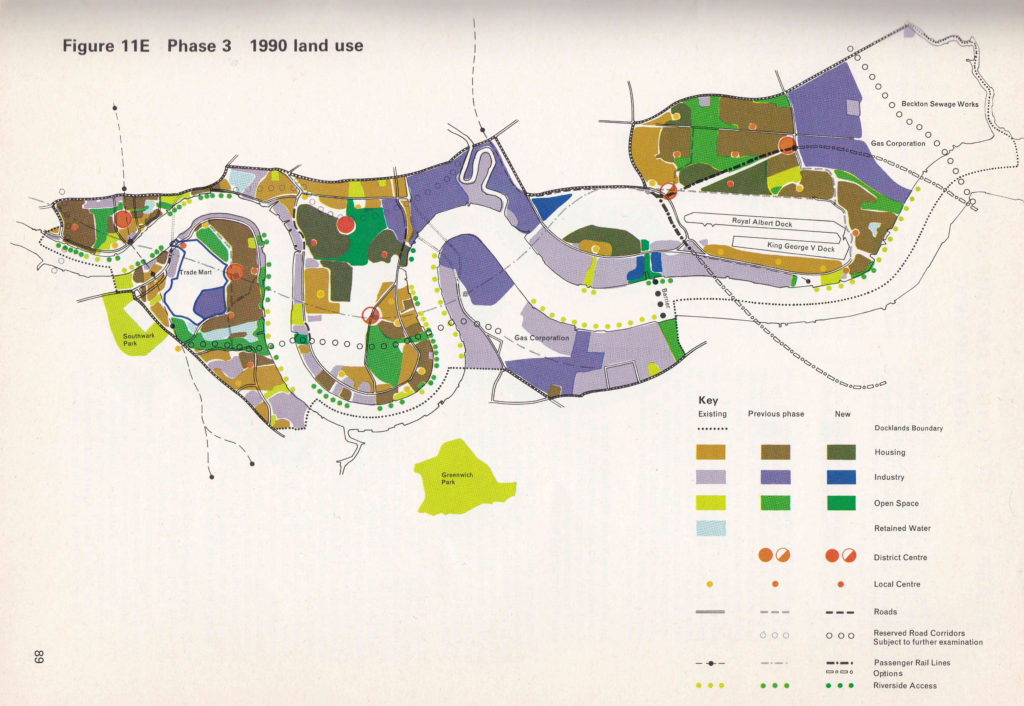

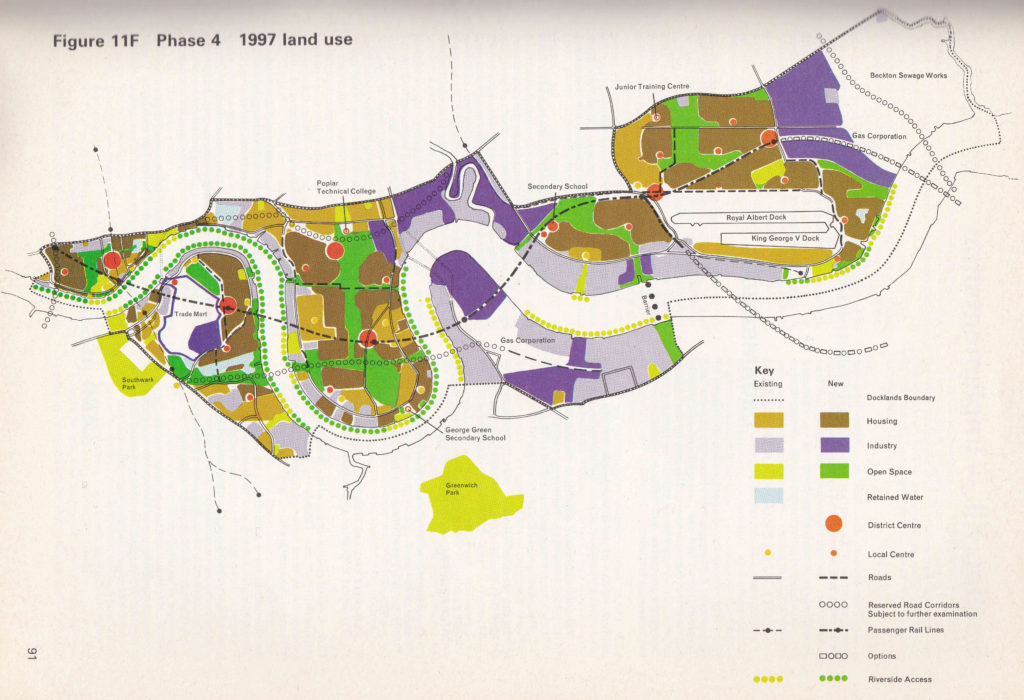

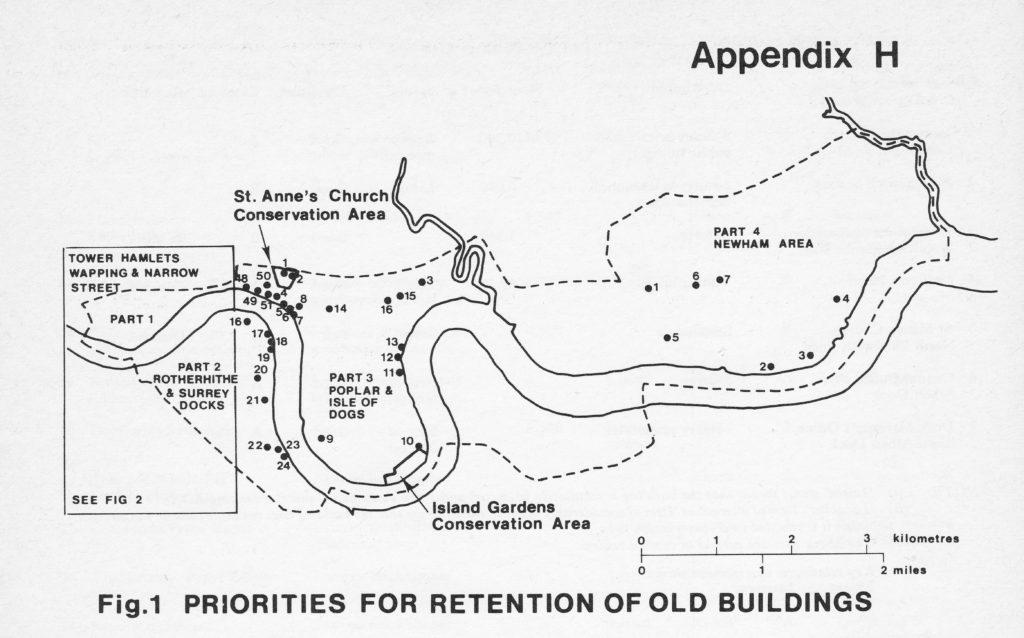

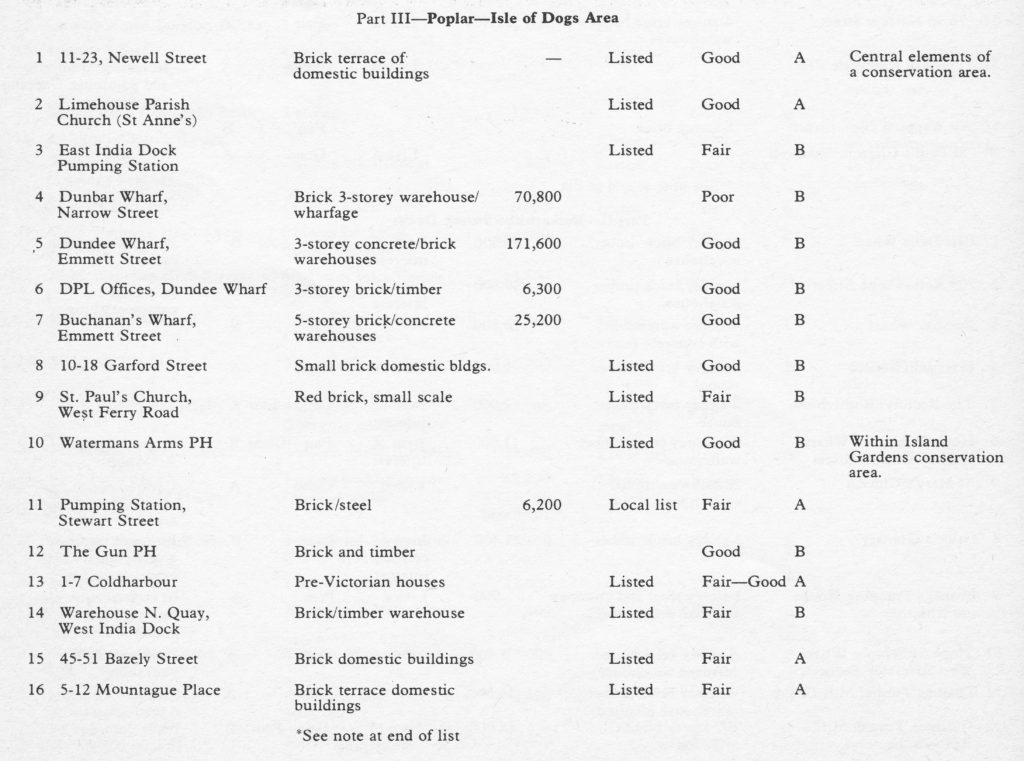

Docklands

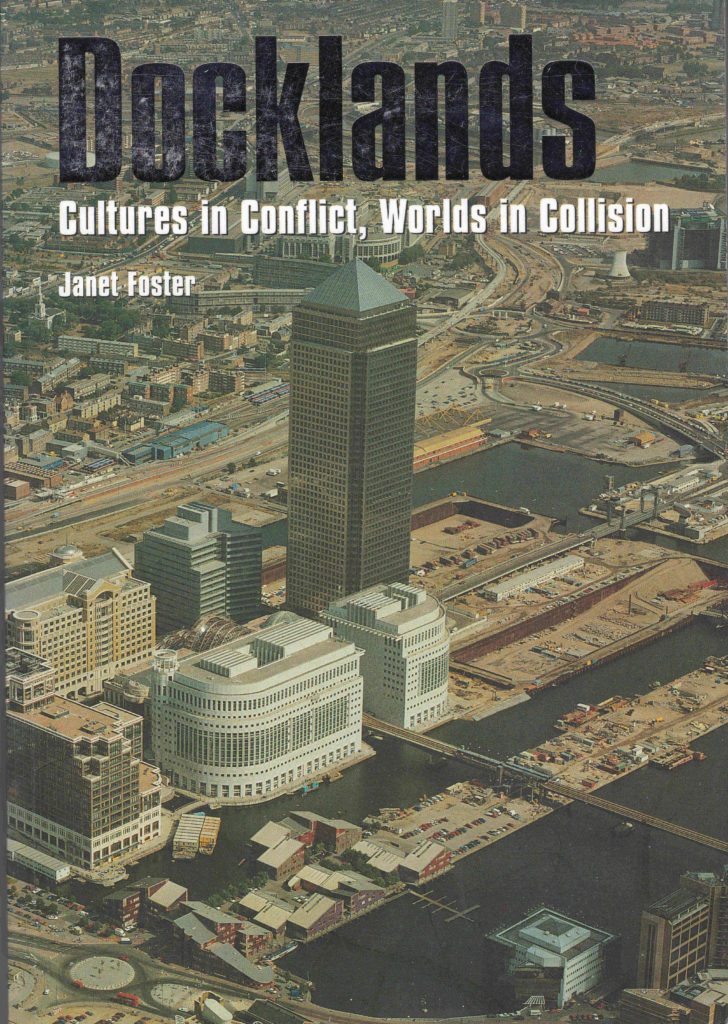

This is the book I have just finished reading, Docklands – Cultures in Conflict, Worlds in Collision by Janet Foster.

This was another second hand purchase. The book, published in 1999 looks to have been originally owned by a student as there are pencil underlining, highlights and comments to key sections throughout. Although the book is an academic text (at the time, Janet Foster was a lecturer at the Institute of Criminology in Cambridge) it is very readable and tells the story of the Docklands regeneration programme, starting with a history of the area, through to the final, chapter “Making Sense Of It All” – an extensive summary of the development programme so far and what the future may hold for the Docklands.

The book makes extensive use of interviews, covering those involved with the development and residents of the area. The book also includes many photos and statistics to illustrate original Docklands and throughout the regeneration programme.

As a detailed, factual record of a key period in Docklands history, I have yet to find a better book.

My pile of London books to read seems to be growing at a rather worrying rate, however thanks to these and many other authors, I am filling in the considerable gaps in my knowledge of this endlessly fascinating city.