Trafalgar Square, one of the most well known locations in London. Visited by thousands of tourists every day, a rallying point for demonstrations, where the 2012 Olympic medals were revealed, and where commemorations and vigils are held, the most recent being after the dreadful terrorist attack at Westminster.

The location of Trafalgar Square is important. It is a key junction, with the Strand leading to St. Paul’s Cathedral and the City, Whitehall leading to the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey and The Mall leading to Buckingham Palace. It is this junction of streets that has resulted in Trafalgar Square being on the route for so many of the processional events the city has witnessed over the last couple of centuries.

Trafalgar Square is also home to Nelson’s Column – the column and the name of the square commemorating the Battle of Trafalgar. On the northern edge is the National Gallery, the church of St. Martin in the Fields is on the north eastern edge and as reminders of the days of Empire the square is fringed by South Africa House, Uganda House and Canada House.

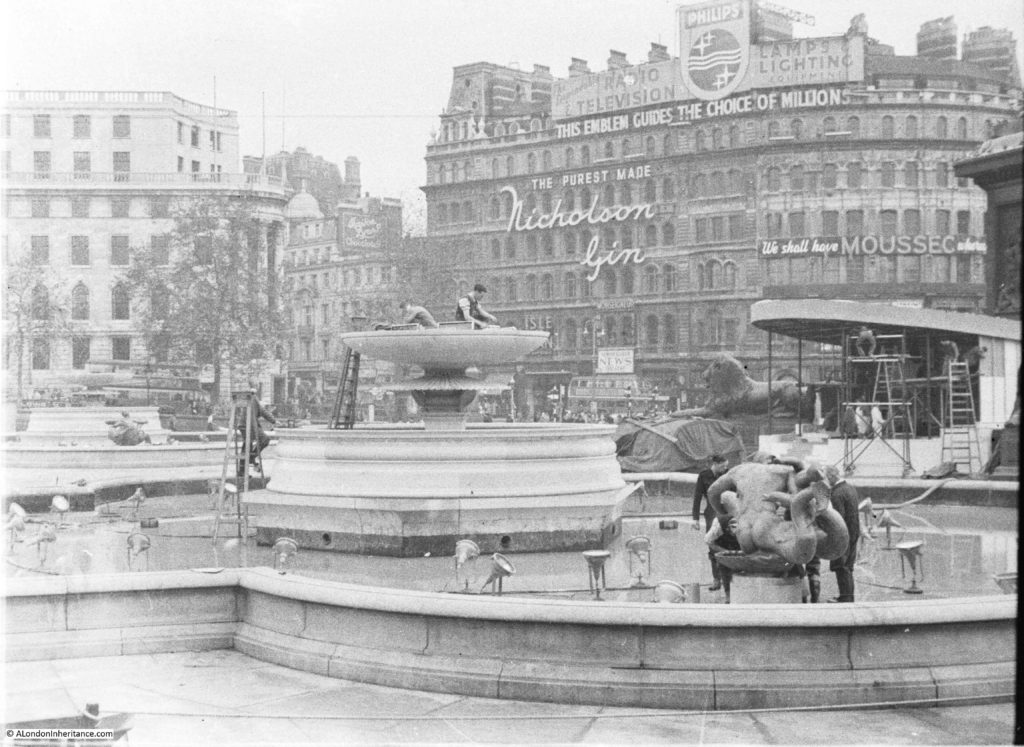

My father took a couple of photos looking across Trafalgar Square 70 years ago in 1947. They show either the preparation for, or dismantling after an event. I do not have a record of the date within 1947 and there are no photos of the event. In 1947 my father was on National Service so I suspect these photos were taken during one of the brief periods back in London on leave.

View across Trafalgar Square looking towards Charing Cross in 1947:

And the same view in 2017:

The following photo is looking towards Whitehall. There is a man working on what appears to be lights in the top of the fountain and more around the base of the fountain. You can see part of a stage on the left, in front of the base of Nelson’s Column.

The same view today – very little has changed in the past 70 years.

Without a date I have not been able to identify the event that required these preparations, and there were no clues in the photos. There were a number of events in and around Trafalgar Square in 1947:

- The wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten took place on the 20th November 1947 and passed the square. Both the square and the surrounding roads were full to capacity with spectators. Police had to form a “crush barrier” with their horses to control the enormous crowds in the square.

- There were a number of demonstrations in the square during 1947. One of which was the “We Work and Want” protest organised by the British Housewives’ League in June 1947. The Aberdeen Press and Journal reported that “More than 100 motor coaches from Scotland and the North of England are expected to carry women to London for Friday’s rally of housewives at the Royal Albert Hall. Seven thousand angry women will attend the meeting, organised by the British Housewives’ League, at which speakers will denounce the Government’s powers of regimentation and food rationing. On Saturday, 30,000 housewives wearing red, white and blue rosettes will march through the West-End of London after a protest meeting in Trafalgar Square.”

- 1947 was also the year of the first gift of a Christmas Tree from Norway. A newspaper report from the time reported that “Trafalgar Square is changed as never before. A 48ft Christmas Tree has sprung up on the west side of Nelson’s column. It arrived last week in the Thames, brought from Norway in the S.S. Borgholm. The tree is a Christmas gift to England’s capital from Oslo, Norway’s capital, and tomorrow the Norwegian Ambassador, Mr. Prebensen, will hand it over to our Minister of Works, Mr. Key. This charming gift, to be lit and decorated with artificial snow, is the outcome of a happy thought of Mr. Pieter Prag, manager of the Norway Travel Association. In Oslo every Christmas a giant fir is set up in University Square, where the children flock to see it. Now, in London’s best-known square, British Children will have a similar treat”

I cannot confirm that my father’s photos were connected with any of the above events. I also found newspaper reports of work in the square in 1947 to repair the electrical cabling and lighting, and to remove the hoardings erected around the base of the column during the war, so it could be this work that my father photographed.

As an aside, whilst reading through newspaper articles and letters on Trafalgar Square, I came across the following letter written to the Kent & Sussex Courier regarding the British Housewives’ League which may be one of the earliest “disgusted of Tunbridge Wells” letters:

“Sir – I recently attended a British Housewives’ League meeting at Christ Church Hall, Tunbridge Wells. the speaker was Dorothy Crisp, chairman of the League.

I was thoroughly disgusted that a woman would use her talent as a speaker to create strife, ill-feeling and unrest, in this Britain of ours. Her whole attitude took me back to the days when Mosley and his gang held meetings.

She stated that she had already booked Scotland Yard for protection at her mass Rally to be held at Trafalgar Square on June 7. Why the secrecy over the name of the other Party who are joining at Trafalgar Square? Are they Fascists, Communists or Conservatives?

I should like to know the real organisation who are paying to cause this unrest and to fool housewives and use them as camouflage to hide sinister intentions that are obviously in mind.”

As far as I can tell, the British Housewives’ League was a right wing organisation that campaigned for women to stay at home and look after the family, christian values and opposition to state intervention and control. Post war austerity and the Welfare State were claimed not to be in the interests of a free and happy home life. There is a fascinating BBC radio programe on the British Housewives’ League. “The League of Extraordinary Housewives” can still be found on iPlayer Radio here. It is well worth a listen

Another of my father’s photos of Trafalgar Square in 1947:

In these 1947 photos there were a number of illuminated advertising signs on the buildings along the southern side of the square, almost like the start of a mini Piccadilly Circus. Luckily this is one area of London where advertising did not subsequently take over.

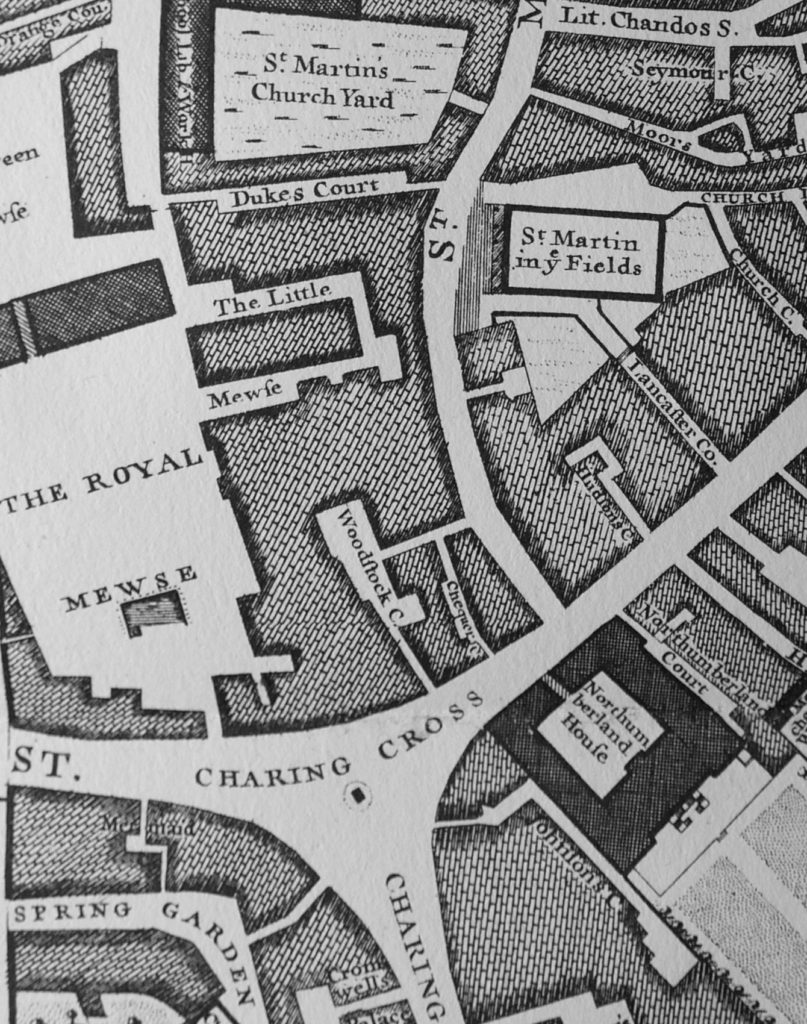

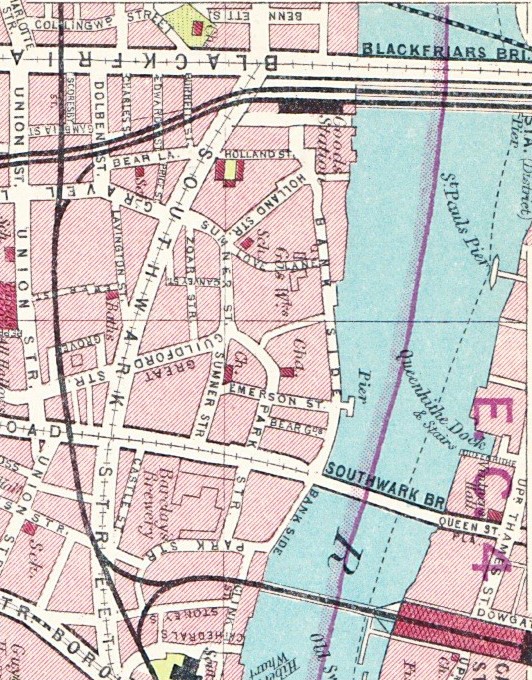

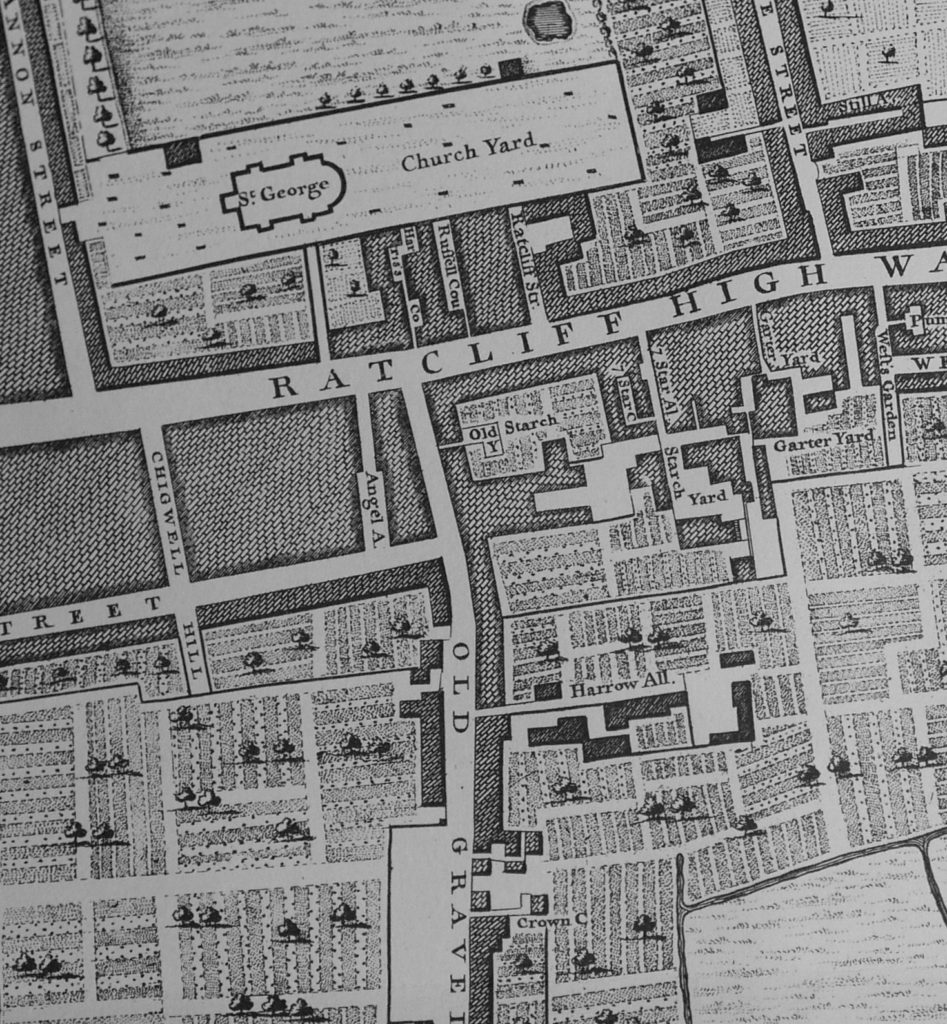

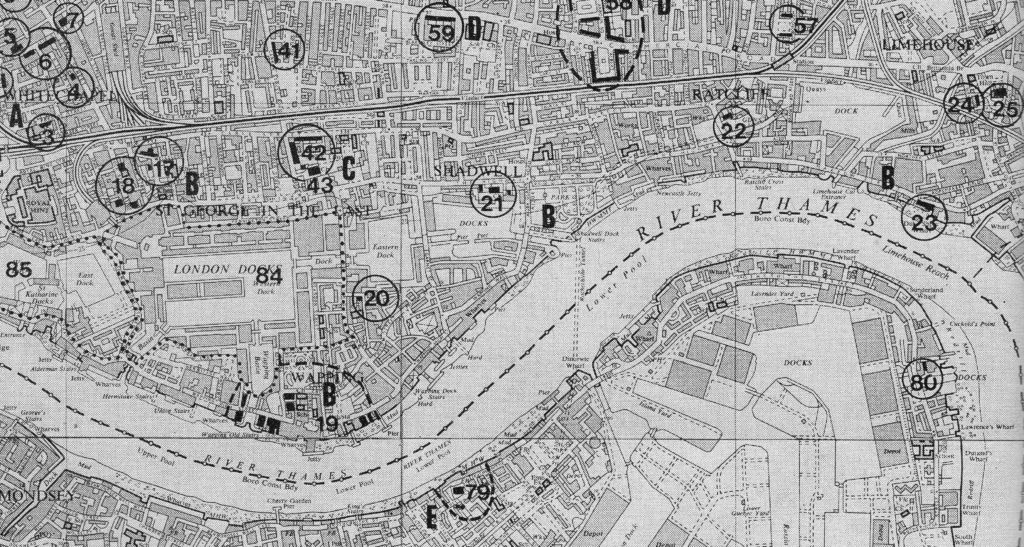

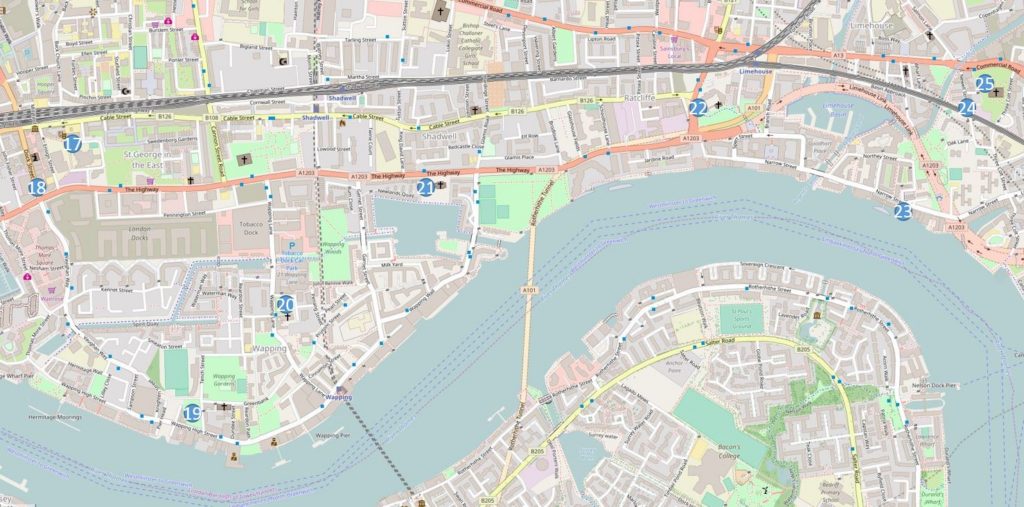

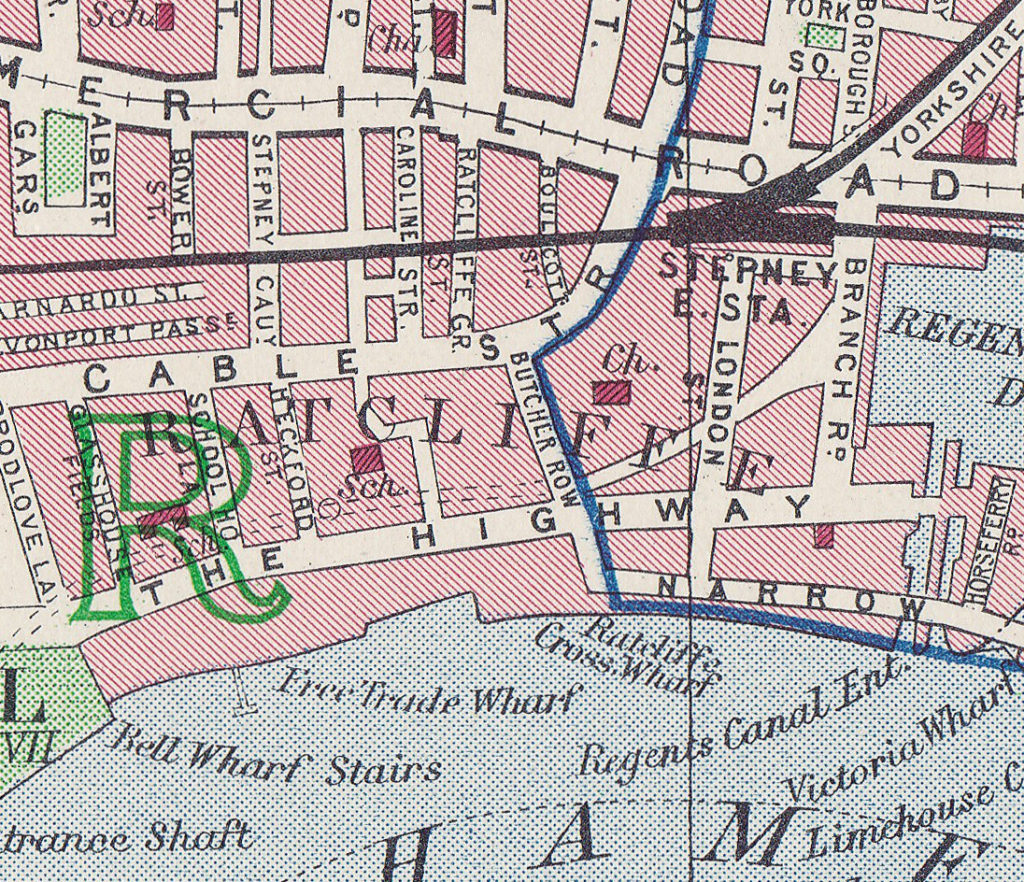

The area now occupied by Trafalgar Square was originally part of the Royal Mews, where horses were stabled and carriages stored along with a reasonably dense area of buildings. The following extract from John Rocque’s map from 1746 shows the area now occupied by Trafalgar Square. The church of St. Martin in the Fields in the upper right is a good reference point to see that all the land to the left and above Charing Cross is now occupied by the National Gallery and Trafalgar Square.

In the lower right of the map is Northumberland House. The following photo shows Northumberland House prior to its demolition in 1874. It was the last remaining of the “Strand Palaces” and had been built in 1605. The lion on top of Northumberland House is now at Syon House.

The preperations for the construction of Trafalgar Square were in the Charing Cross Act of 1826. This enabled the land to be used for an open square and the National Gallery.

Work on the National Gallery commenced in 1832 with the Gallery being completed in 1838 to a design by William Wilkins. Trafalgar Square was constructed over a couple of decades. The core design was by Charles Barry, although his design did not include the fountains and he opposed Nelson’s Column being part of the square, arguing that it would dwarf the National Gallery. The fountains were completed in 1845 and the layout of the square in 1850.

Work on Nelson’s Column began in 1839 with the statue of Nelson being raised into position in November 1843. The bronze lions were added in 1867.

There were a number of alternative proposals for the design of the naval monument, as Nelson’s Column was originally called during the planning stages, including the following by John Goldicutt from 1833 (©Trustees of the British Museum).

Trafalgar Square today, continues as a central hub towards the west of London and is always busy. The terrace area in front of the National Gallery is from where my father took his photos looking across the square. Today, it is mainly selfies in front of the National Gallery and with the square in the background, and also the home to that essential visitor attraction – the floating Yoda, of which there are far too many both here and across London.

Although the more traditional form of street artist still survives:

One of the major attractions for children at Trafalgar Square was feeding the once significant number of pigeons. Vendors would sell seed in the square and I remember doing this as a child in the 1960s. Feeding the pigeons was made illegal in 2003 which has resulted in a much improved environment – although probably rather boring for small children. Today there are still signs stating that pigeon feeding is banned.

On the south east corner of the square is the very small building that was used as a police lookout during major events in the square.

Trafalgar Square’s location puts it on the route for any procession between the City, St. Paul’s Cathedral, Buckingham Palace, the Place of Westminster and Westminster Abbey. Crowds have long used Trafalgar Square as a location to watch these events and in recent decades it provides a good location for the media to assemble.

My father also took a number of photos on the morning of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on the 2nd June 1953. The full post with these photos can be found here, and I have included two from Trafalgar Square below. The first photo is looking north from the southern edge of the square and shows crowds around one of the lions.

The same view today:

I wonder how many people have sat in front of the lion over the years. Whilst I was there, numerous children were being lifted to sit for photos between the paws of the lion.

Another of my father’s photos from 1953:

And again in 2017:

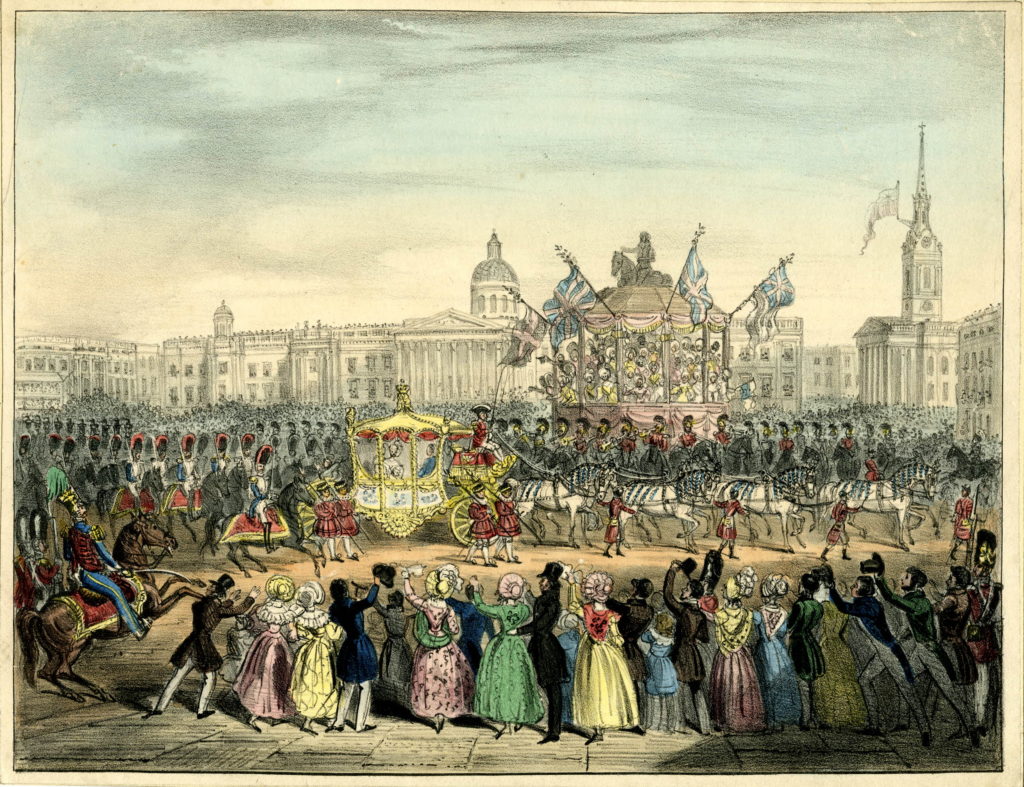

And it is not just in this century that Trafalgar Square has featured in such events. This drawing from 1838 shows the procession of Queen Victoria to her coronation passing the square, with the National Gallery in the background and the church on St. Martin in the Fields on the right (©Trustees of the British Museum).

The notable feature absent from the above drawing is Nelson’s Column. Work on the column would begin the following year.

As well as being a bystander to events, the square has also been the subject of major ceremonies, for example on the Centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar on the 21st October 1905. The square was crowded and Nelson’s Column decorated for the special event as shown in the postcard below:

It was not just the centenary event that attracted crowds. The Pall Mall Gazette reports on the 11th October 1905 “Steeplejacks in Trafalgar Square – Preparations for the decoration of the Nelson Monument in Trafalgar Square in connection with the forthcoming anniversary have already been commenced. This morning the operations of three steeplejacks, who were engaged in girding the column with stout ropes from ladders strapped to the structure, were watched with great interest by a large crowd.”

Ladders strapped to the side must have been a rather risky exercise given the lack of health and safety at the start of the 20th century.

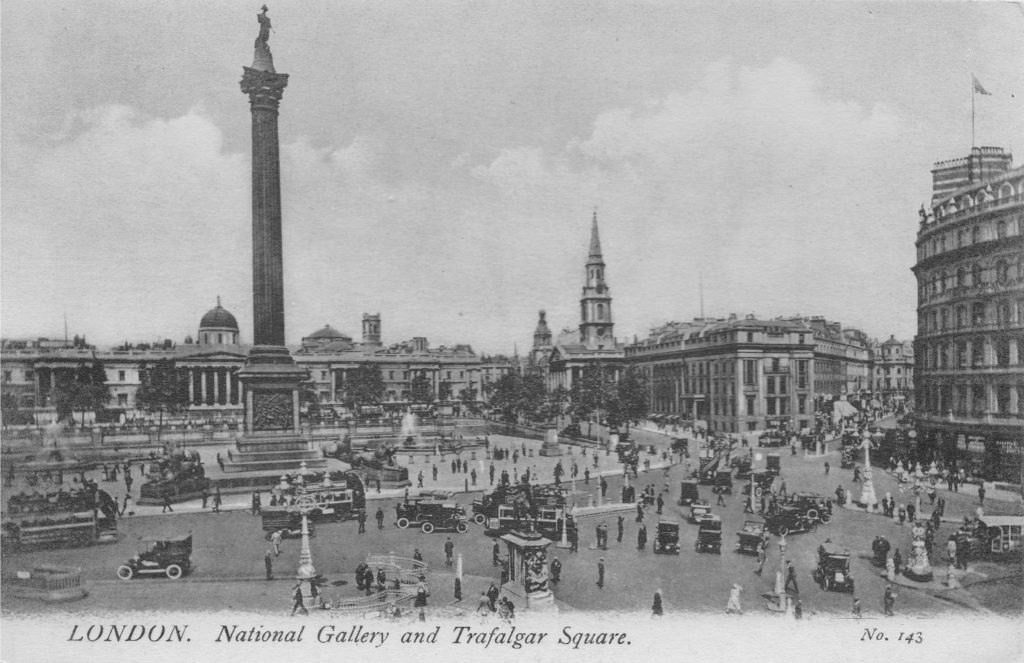

Another view of the square in the early 20th century. The traffic and complexity of the road layout remains to this day and is a result of the square being at the point where so many major streets meet.

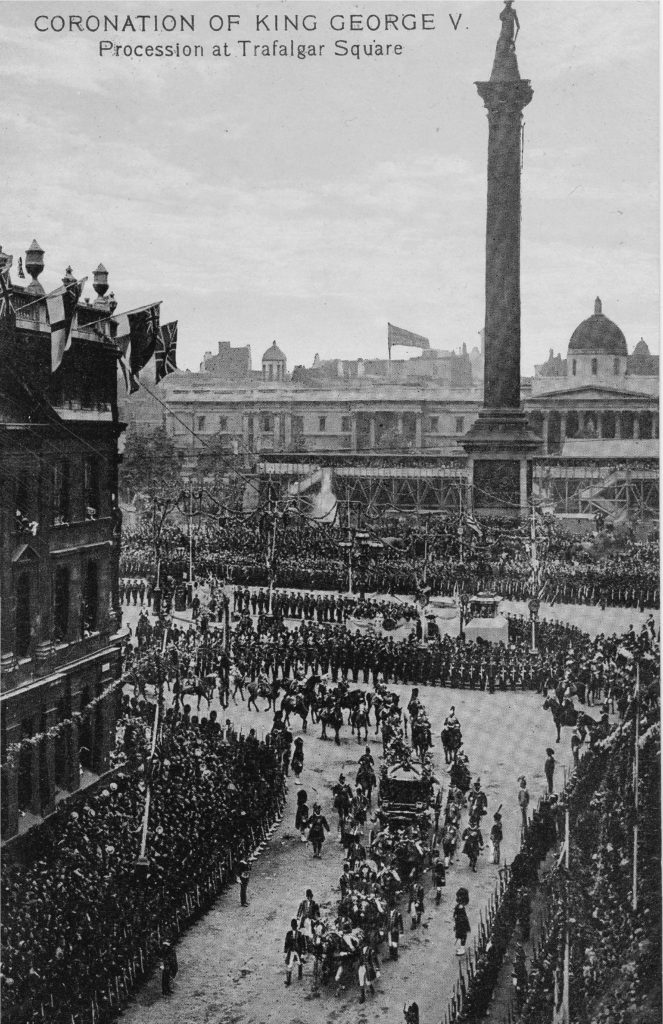

Although I have not checked, I suspect Trafalgar Square has featured in the majority of Coronations. The following postcard shows the procession during the coronation of King George V passing Trafalgar Square on the 22nd June 1911.

I have been working out of the country for much of the past week, and as with most of my posts, I feel I have only just scratched the surface of the history of this area. There is so much more on the area prior to the construction of Trafalgar Square, the work on building the square and column, the fountains and their water supply, the many other events that have taken place in and around Trafalgar Square (for example whilst researching 1947 I also found the story of an alleged terrorist bomb blast at the Colonial Welfare Club in St. Martin’s Place off Trafalgar Square which injured six airmen). You can though read about one of the tunnels under Trafalgar Square here.

But at least if you are ever in a London trivia quiz and you need to know who was responsible for the first Trafalgar Square Christmas Tree, it was Mr. Pieter Prag, Manager of the Norway Travel Association.