The last weekend in February marks the annual anniversary of the blog, and this year, 2024, it is ten years since my first post on A London Inheritance.

The blog started as a way to find and document the locations of the photos my father started taking in 1946, along with just generally exploring the city, and I hope it has kept true to this approach.

I have learnt so much about the city in the ten years, discovering the story of places that I have walked past for years, with the blog now providing the incentive to stop, explore and discover the history of places that I once took for granted.

I have also learnt so much from the comments to the posts, so thank you to everyone who has left a comment on a post – they are all read with interest.

And my thanks to you for reading the blog, to the thousands who subscribe to the Sunday morning post. I try to keep them below 4,000 words (which is probably too long), so sorry for some of the longer posts.

Readership has and still does, continually increase, and the blog is now getting well over 500,000 views a year – a figure that I could never have expected when I started back in 2014.

Thank You.

Walks

I started doing guided walks based on the blog a couple of years ago for a number of reasons.

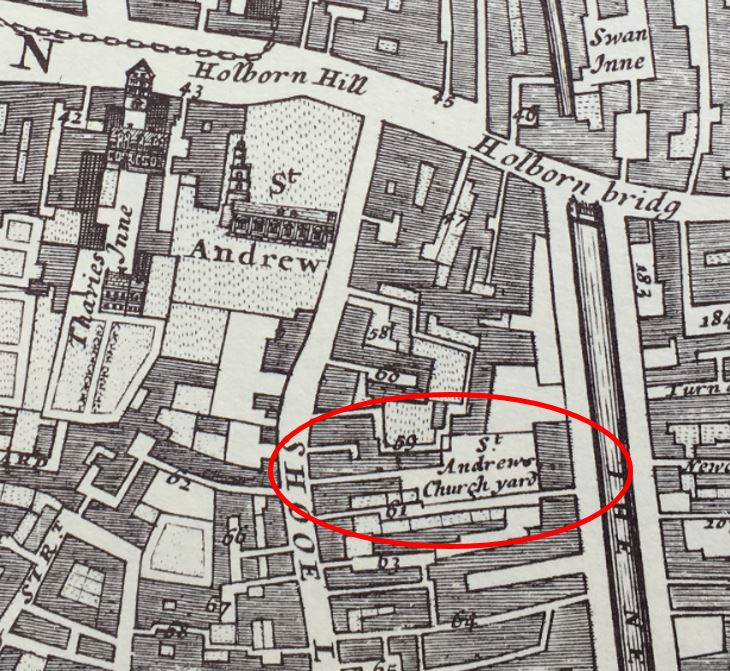

There are blog posts about individual stories or an area scattered across the ten years of posts. They do not come together to tell a comprehensive story of a specific area, such as Wapping, Limehouse, or the Southbank and Barbican, and the walks enable me to do this.

It is also brilliant to meet readers, and to show some of my father’s photos from the place where they were taken.

And again, I learn much from those who are on the walk.

I will be continuing walks this year, and hope to start a new walk in the coming months which explores an area of the City which could well be significantly redeveloped in the coming years, and is a place with a long and complex history, going back 2,000 years.

A Look Back from 2014 to 2024

To record the fact that the blog has reached ten years of continuous Sunday morning posts, I thought I would take a look back through a sample of posts over the years.

It is a random sample, apart from the post for 2014, which has to be the post that started A London Inheritance (click on the headings to visit the post):

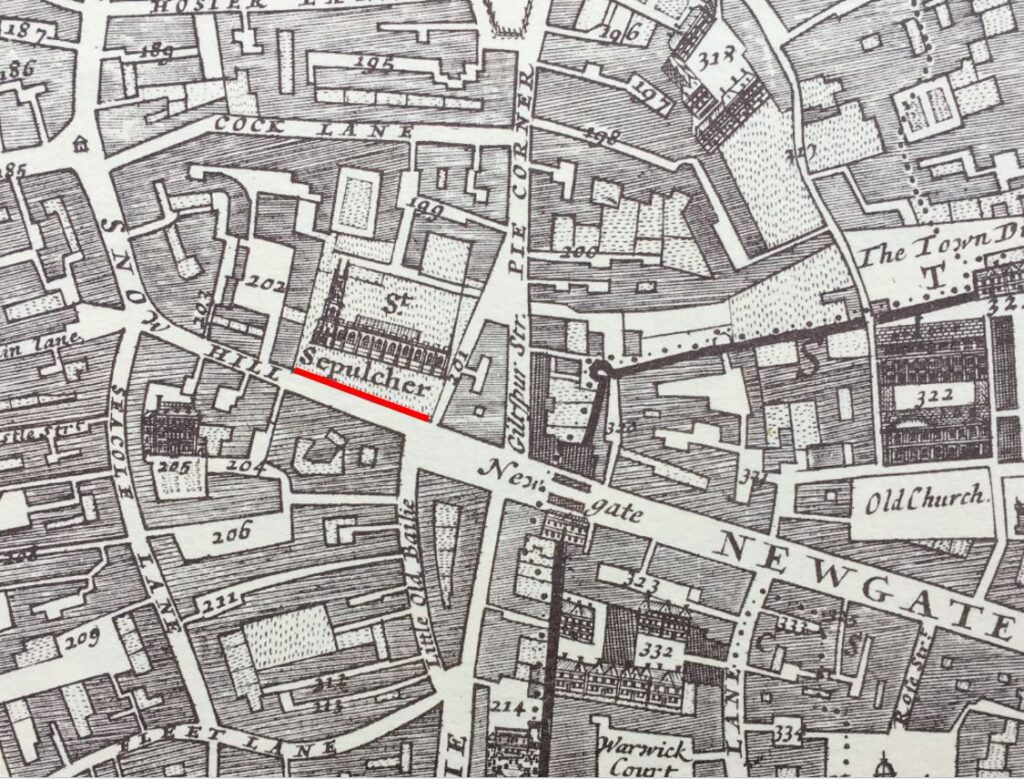

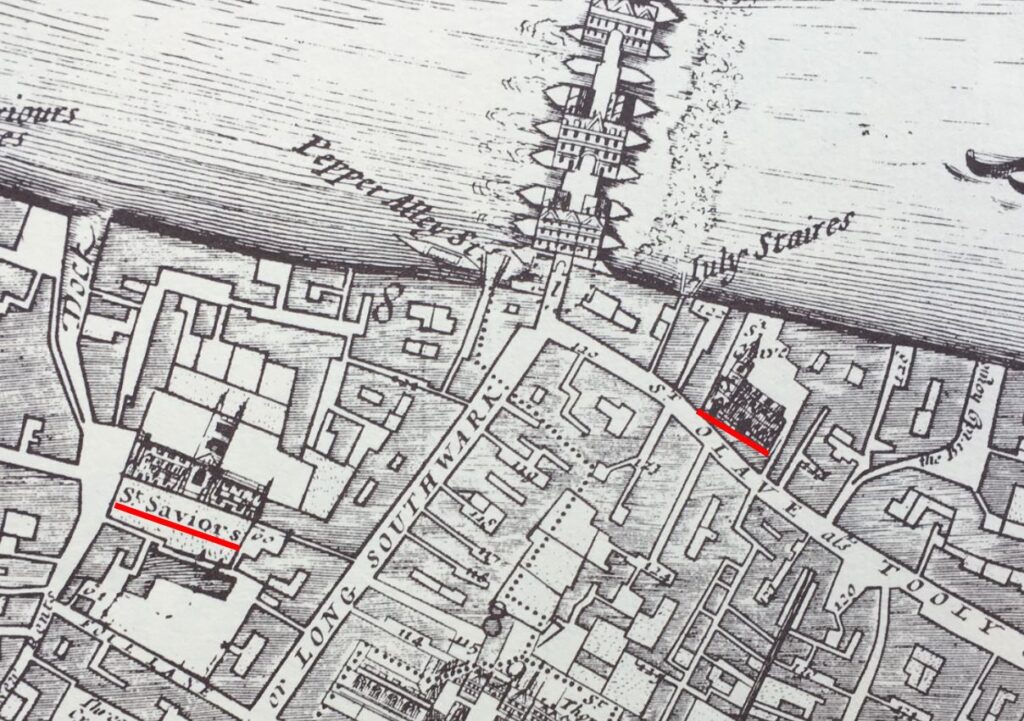

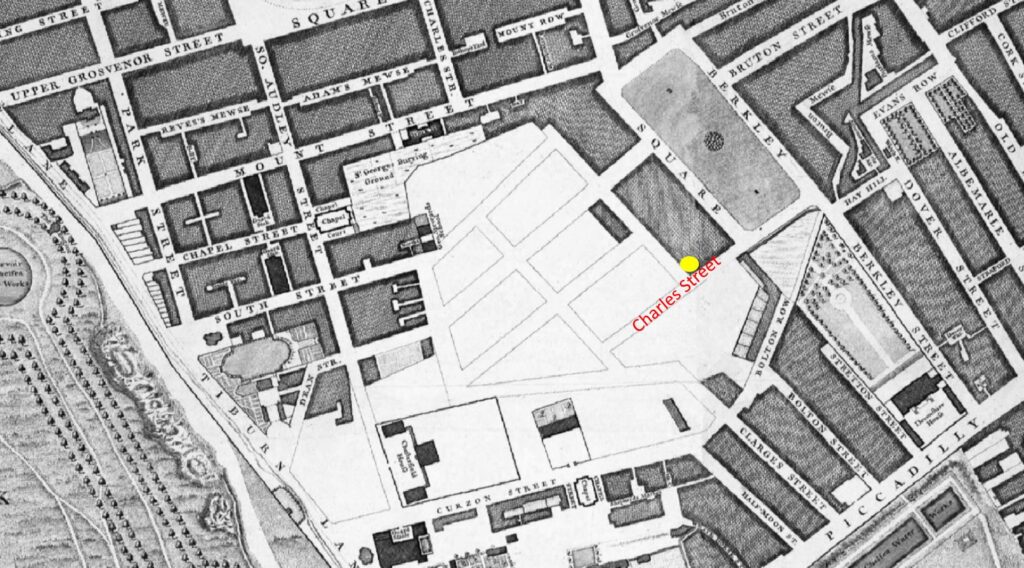

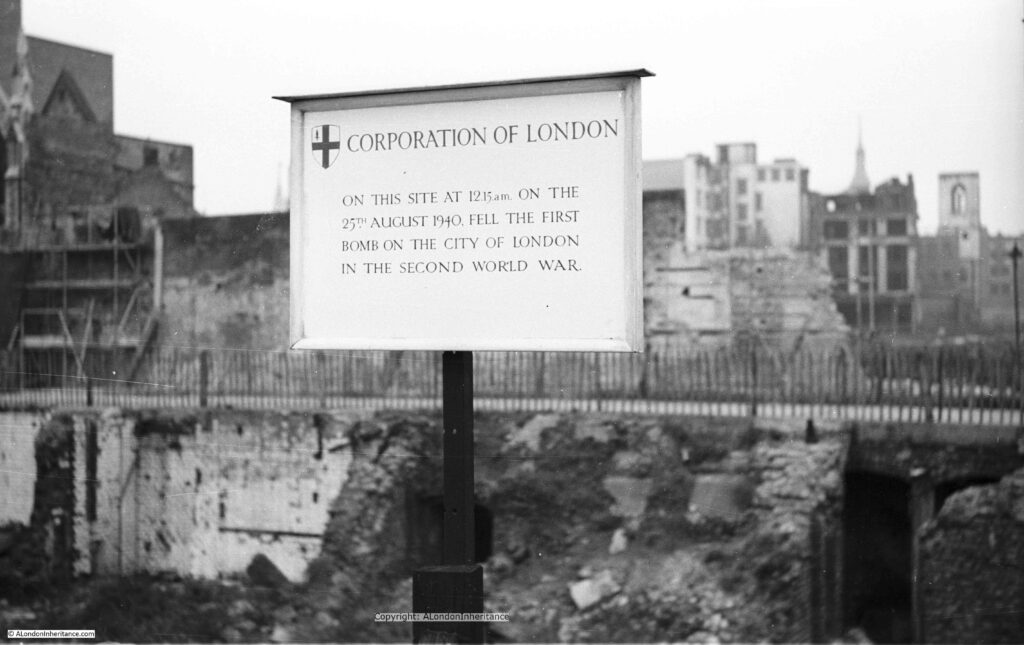

2014 – The First Bomb and a Church Shipped to America

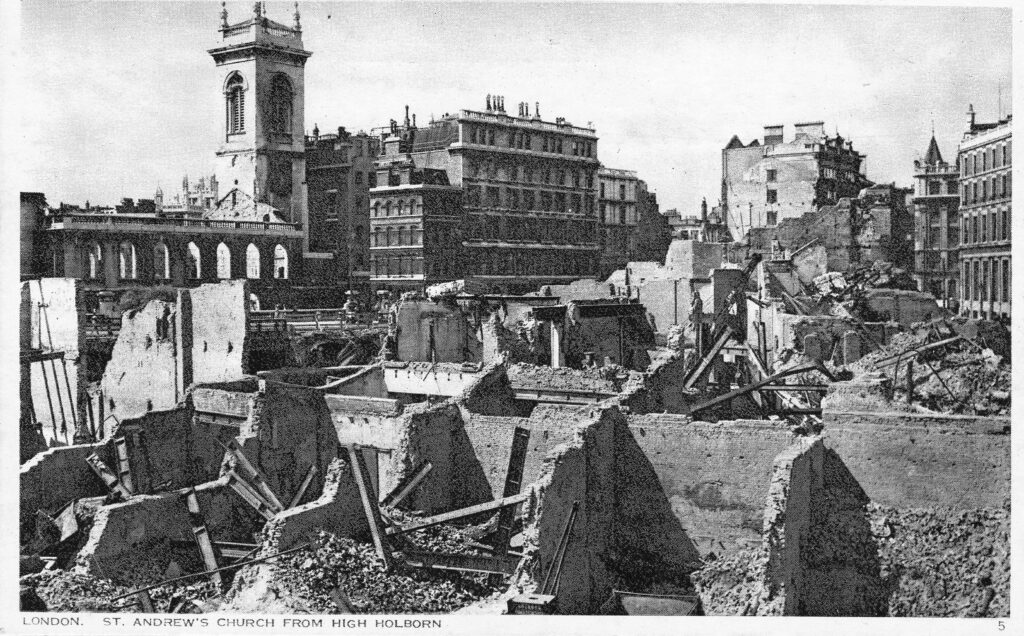

My very first post started with a photo of a plaque put up by the Corporation of London recording the first bomb to fall on the City of London. It seemed an appropriate photo to start the blog, as so many of my father’s photos show the impact of the war on the city.

He grew up in London during the war. He was evacuated for a couple of weeks, however his parents wanted him to return home, and he left a written record of both the terror and excitement of growing up in London in wartime, and started taking photos in 1946.

After this first attack on the 25th August 1940, heavy bombing started on Saturday September 7th and continued for the next 57 nights. London then endured many more months of bombing including the night of the 29th December 1940 when the fires that raged were equal to those of the Great Fire of 1666. Hundreds of people were killed or injured, damage to property was enormous and 13 Wren churches were destroyed. Or the night of the 10th May 1941 when over 500 German bombers attacked London. The alert sound at 11pm and for the next seven hours incendiary and high explosive bombs fell continuously across the city.

Behind the sign is a devastated landscape, not a single undamaged building stands, to the right of the photo, the shell of a church tower is visible. All this, the result of months of high explosive and incendiary bombing.

2015 – From the City to the Sea

The Thames is the reason why London is located where we find it, and why it has developed into the city we see today, however with the closure of the docks and the industries that depended on the river, we seem to have lost that connection.

I had my first trip along the river from the City out to the sea in 1978, and since then it has been fascinating to watch how the river has changed. I also have a series of photos that my father took on a similar journey in the late 1940s. I am working to trace the exact locations and will publish these in a future post.

In 2015 I took the opportunity for another trip down the river aboard the Paddle Steamer Waverley, from Tower Pier out to the Maunsell Forts.

The Paddle Steamer Waverley is the last sea going paddle steamer in the world, built on the Clyde in 1947 to replace the ship of the same name sunk off Dunkirk in 1940.

Five posts covered the journey from Tower Pier, out to the Maunsell Forts in the Estuary.

The following photo is from the return journey in the evening, with the ship about to pass through the Thames Barrier. Green direction arrows clearly point to the channel that should be used to navigate through the barrier. The office blocks on the Isle of Dogs can be seen in the distance:

It really was an interesting journey, and the Waverly appears to be making a return visit to London later this year.

2015 – Swan Upping

In 2015, I went Goring lock, to see one of the stops in that year’s Swan Upping route.

This is my father’s photo of Mr. Richard Turk who was the Vintners Swan Marker and Barge Master. He held this position from 1904 to 1960. A remarkable period of time to hold the role and the changes he must have seen along the Thames as Swan Upping was performed each year must have been fascinating.

Swan Upping is an event which takes place in the third week of July each year. Dating back many centuries, the event has roots in the Crown’s ownership of all Mute Swans (which dates back to the 12th century), ownership which is shared with two of London’s livery companies, the Worshipful Company of Vintners and the Worshipful Company of Dyers who were granted rights of ownership in the 15th century.

Swan Upping is the annual search of the Thames for all Mute Swans, originally to ensure their ownership is marked, but today more for conservation purposes (counting the number of swans and cygnets, checking their health, taking measurements etc.), although the year’s new cygnets are still marked.

2016 – A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain

Throughout the last ten years, I have written a number of posts about the Festival of Britain, and in 2016 wrote several posts covering the Southbank festival site, the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture in Poplar, the Pleasure Gardens in Battersea etc.

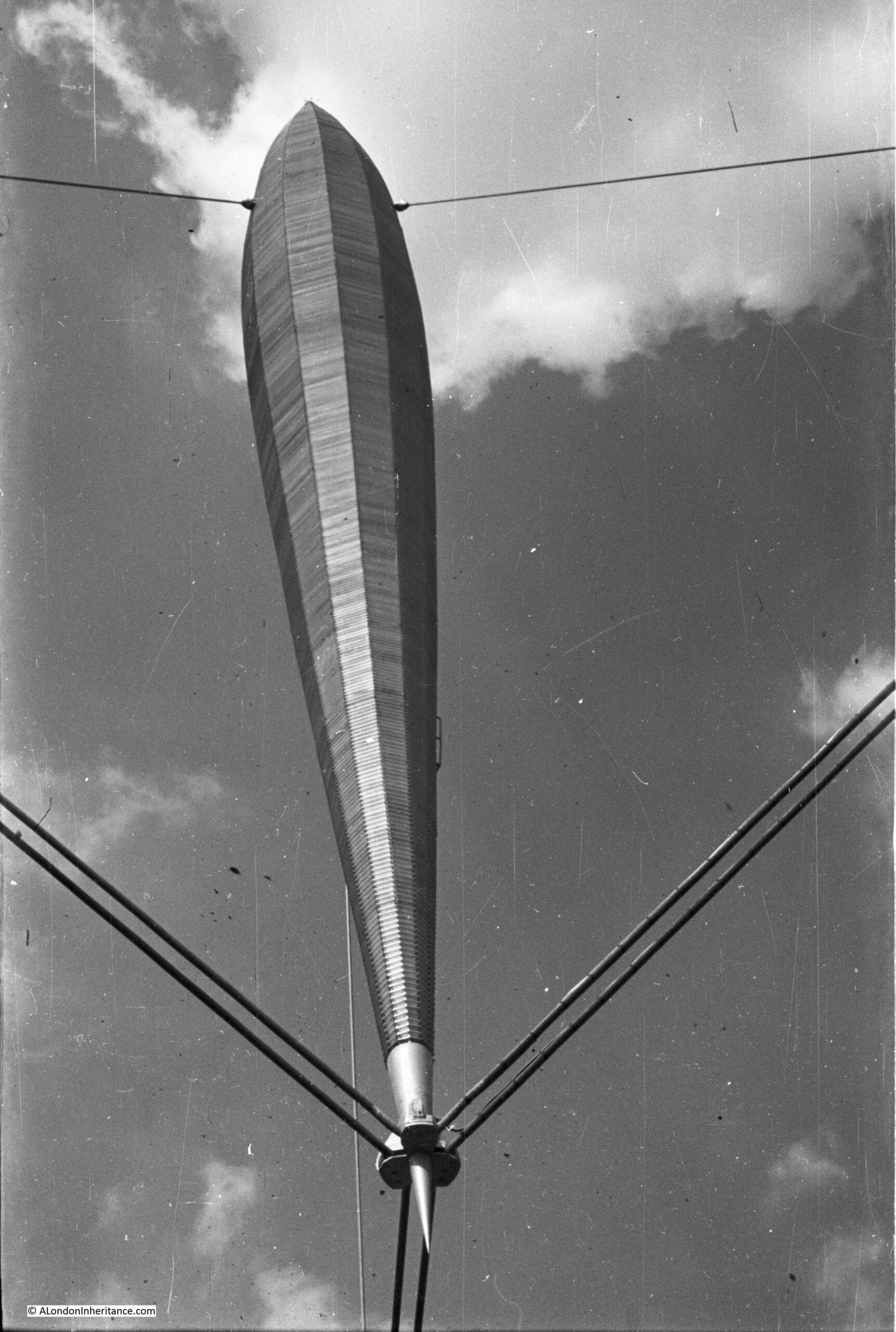

This was my father’s photo taken from the base of the Skylon, looking up at the structure:

The design for the Skylon was the result of a competition for a “vertical feature” for the festival site. Of 157 entries, the design by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya along with the engineer Felix Samuely was chosen.

The main body of the Skylon was 250 feet in height, add in the suspension off the ground and the total height was 300 feet. Three sets of cables held the Skylon in a cradle at the lowest point, and half way up at the thickest point a set of guy wires held the Skylon in a vertical position.

Aluminium louvered panels were installed on the outer edge of the Skylon and lights were installed inside, so during the day, the Skylon would sparkle in sunshine and at night it would be lit from the inside.

The name for the Skylon was also chosen in a competition. The winning entry was from a Mrs. Sheppard Fidler and the name was a combination of Sky and the end of Nylon (the latest modern invention), which when combined gave the futuristic sounding name of Skylon.

2016 – Building the Royal Festival Hall

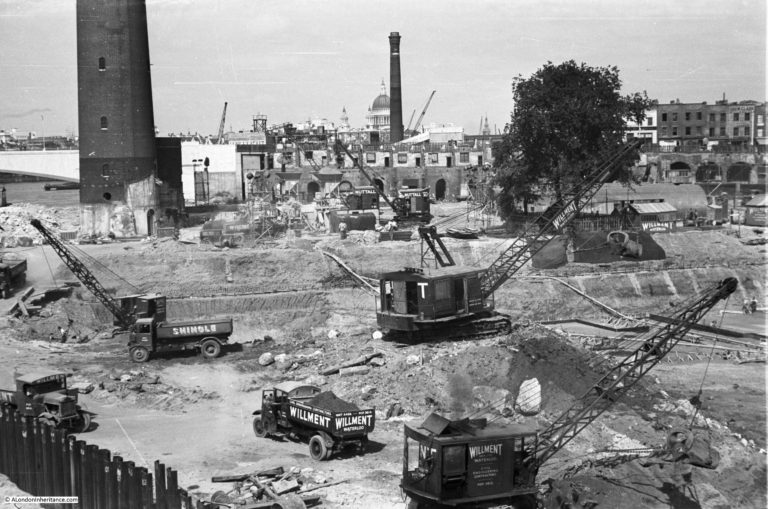

Another of my 2016 Festival of Britain posts was on the construction of the Royal Festival Hall, the only building that remains on the Southbank from the Festival. My father had taken a number of photos both before the site was cleared and during the building’s construction, including a series showing the foundations being prepared:

Work on the foundations started in May 1949 with bulk excavation of the whole area – as clearly seen in the photos above that my father took of the area. Bulk excavation was used as the easiest way to clear the area needed for the foundations. The centuries of previous construction on the site included the remains of the old water works along with the brewery which was built on a 6 foot thick mass concrete raft.

There was a large amount of work to prepare, which included sinking well points and then pumping out water which started on the 17th June 1949, when, within four days the ground water level was reduced to 13ft below the ordnance datum. A huge volume of water was extracted, with at the start of pumping 150,000 gallons of water per hour were being pumped out, and even after the site had been “de-watered”, pumping was still needed of 80,000 gallons per hour to keep the area of the foundations dry.

A total of 63,000 cubic yards of materials were removed for the foundations.

2017 – Flying Over London

I will take any opportunity to see London from a high point, including flying above the city, and in 1979 and 1983, I took a couple of flights in a vintage de Havilland Dragon Rapide, and I have published a number of posts with some of the photos from these flights, including this example:

The above photo shows parts of Poplar at the top, and the northern end of the Isle of Dogs with from the top, the West India Dock (Import), the West India Dock (Export) and the South Dock. If you look just above the top dock, over to the right is the spire of a church, this is All Saints Church, Poplar. The Balfron Tower can be seen just behind the spire of the church.

Hard to believe that this is now the Canary Wharf development and One Canada Square is now in the centre of these docks.

2017 – St. James Gardens – A Casualty Of HS2

In 2017, I started an annual post, recording the construction of the new HS2 station at Euston, starting with St. James Gardens, which would close soon after I had taken the photos in this blog post.

Before construction could start, the gardens, which had been a cemetery, needed to be excavated to remove the many thousands of bodies that were still buried beneath the grass, footpaths and gardens.

2017 – Clifton Suspension Bridge

As well as London, my father also took very many photos of places visited during Youth Hostel / cycling trips in the late 1940a / early 1950s with friends from National Service.

I have also been trying to visit all these locations.

One of the sites he photographed was the Clifton Suspension Bridge, and in 2017 I had the opportunity to look inside the hidden vaults beneath one of the abutments supporting the bridge, and I posted some of these photos, along with my father’s 1952 photos of this bridge.

Although the bridge is in Bristol, there is still a significant London connection, as recorded in this report on the bridge from 1864:

“Mr. Brunel, as it happened, had been the engineer of Hungerford Bridge; and when, therefore, its chains had to be pulled down and to give place to the bridge of the Charing-cross Railway, it occurred to Mr. Hawkshaw to have them applied to the completion of one of Mr Brunel’s bridge designs. For such a purpose the money was soon forthcoming. A new company, under a new Act and presided over by Mr. Huish was started, with a capital of £35,000. The chains of Hungerford Bridge were purchased for £5,000; the stone towers built by Mr Brunel for the old company, for £2000. Two years ago the work of slinging these chains began and the bridge is now finished.“

Hungerford Bridge was the bridge built across the Thames to the old Hungerford Market, on the site of Charing Cross Station, before the current railway bridge was built.

2018 – The Streets Under The HS2 Platforms And Concourse

In 2018 I walked the streets to the west of Euston that would soon be demolished as part of the HS2 project. The following photo shows the Bree Louise pub, at the junction of Euston Street and Cobourg Street, which had closed not long before the photo:

The pub dates from the early 19th century and was the Jolly Gardeners until being renamed by the most recent landlord as the Bree Louise, the name of the landlord’s daughter who died soon after birth.

The Bree Louise was a basic, but superb local pub and it was sad to see how quickly after closing at the end of January, the pub has taken on such air of being abandoned.

Everything in the above photo has now been demolished and is part of the HS2 construction site.

2018 – A Forty Year Return Visit To A Secret Nuclear Bunker

2018 included a rather somber post, describing a return to a location I was last at forty years earlier.

In the late 1970s, after leaving school, I started an apprenticeship with British Telecom (or Post Office Telecommunications as it was then). It was a brilliant three year scheme which involved both college and practical experience moving through many of BT’s divisions and locations. For a couple of months I was based at the telephone exchange at Brentwood, Essex. A typical day would involve maintenance and fault fixing on the telephone exchange equipment, however at the start of a day that would be rather different, the Technical Officer in charge was giving out jobs, and one job involved fixing a fault at a rather unique location – a secret nuclear bunker.

These were the years when a nuclear war was still a possibility, when the Government issued the Protect and Survive booklet, and in 1984 the BBC drama Threads appeared on TV – one of the most unsettlingly programmes I think I have ever watched.

2019 – St Giles Cripplegate and Red Cross Street Fire Station

The subject of this post, was a photo taken in 1947, looking across a rather devastated landscape to the church of St Giles Cripplegate:

There are three main features in the photo, two of which survive to this day, although the area is now completely different following the development of the Barbican.

The church of St Giles Cripplegate is in the centre, the church looks relatively unscathed, however it suffered very badly and lost the main roof and contents of the church.

To the right of the church is a pile of rubble, and to the right of this, is the round shape of a Roman bastion, which can still be seen.

The large building on the left was the Red Cross Street Fire Station, demolished as part of the final land clearance in preparation for the build of the Barbican.

2019 – Crow Stone, London Stone and an Estuary Airport

In this post, I finally managed to get to a place I had been wanting to visit for years. It took a bit of planning, but took me to a location that still has evidence of the City of London’s original jurisdiction over the River Thames.

To the west of Southend, on the borders with Leigh, and by Yantlet Creek on the Isle of Grain, there is a line across the River Thames which marked the limits of the City of London’s power. Where this line touched the shore, stone obelisks were set up to act as a physical marker.

The above photo shows the London Stone at Yantlet Creek. The early 4 am start to get there was well worth it – standing at the London Stone at 6:45 as the sun rose over the Thames Estuary, in such an isolated location, was rather magical.

2020 – The House They Left Behind

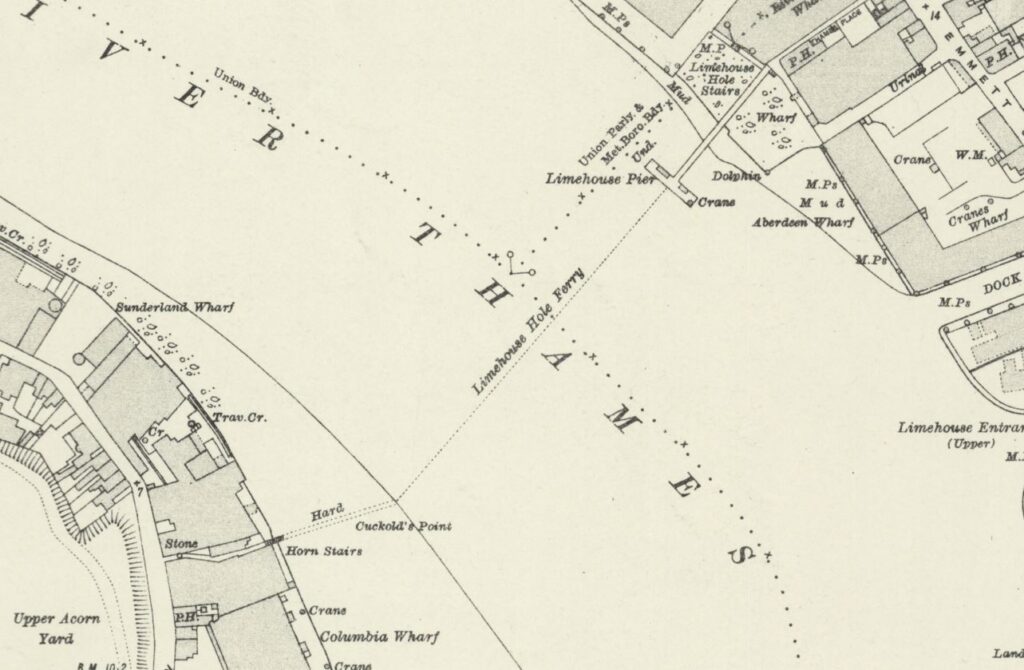

One of 2020’s posts included a trip to Limehouse, to find the site of the following photo from1986, which shows the side of a building where the adjacent buildings have obviously been demolished. The building has “The House They Left Behind” painted in bold black letters on a white background, with below, the original build date and a restoration date of the year before the photo was taken.

The pub was originally called the Black Horse, and was one of four in a small area of Narrow Street and Ropemakers Fields. Today, the only pub remaining is the Grapes.

The name change from Black Horse was to describe the position of the pub after demolition of every other building on Ropemakers Fields, and the Barley Mow Brewery, when the pub became “The House They Left Behind”. It is now residential.

2020 – A Very Different London

2020 was the start of COVID, with the first lockdown starting in March. London became a very differenet place, and the city is still reacting to the impact of the virus and lockdown.

The following photo was taken along a very quiet Cromwell Road, with the Victoria and Albert Museum on the left:

On the Monday afternoon before the first lockdown, I had to take a relative to Guy’s and St Thomas Hospital at London Bridge (fortunately nothing to do with the Coronavirus). The hospital had advised not to take public transport, so the only other option was to drive.

Although this was before the formal lock down and the direction to stay at home, I had already stopped walking around London and was missing the experience of walking the city, particularly as the weather was so good.

To take advantage of a drive up to London Bridge, I mounted a GoPro camera on the dash of the car and left it filming the journey there and back.

It was a London I had not seen before on a Monday afternoon, more like a very early Sunday morning. Very few people on the streets and not much traffic. I cannot remember driving in central London on a weekday without any queues. The only time I needed to stop was at traffic lights.

A frightening reminder of the impact of the virus.

2020 – Hidden London – Moorgate

The London Transport Museum have run a brilliant series of tours of the hidden side of London’s transport infrastructure, and in February 2020, on a chilly Saturday afternoon, I arrived at Moorgate looking forward to walking through the hidden tunnels of another London underground station.

The above photo shows the remains of a Greathead Tunneling Shield at Moorgate. This was the invention of James Henry Greathead, who developed Brunel’s shield design, from rectangular, with individual moveable frames, to a single, circular shield. Screw jacks around the perimeter of the shield allowed the shield to be moved forward as the tunnel was excavated in front of the shield, with cast iron tunnel segments installed around the excavated tunnel immediately behind the shield.

Greathead’s first use of his shield was on the Tower Subway.

He died in 1896, before the Lothbury extension at Moorgate, however his shield design was so successful that it became the standard design for shields used to excavate much of the deep level underground system.

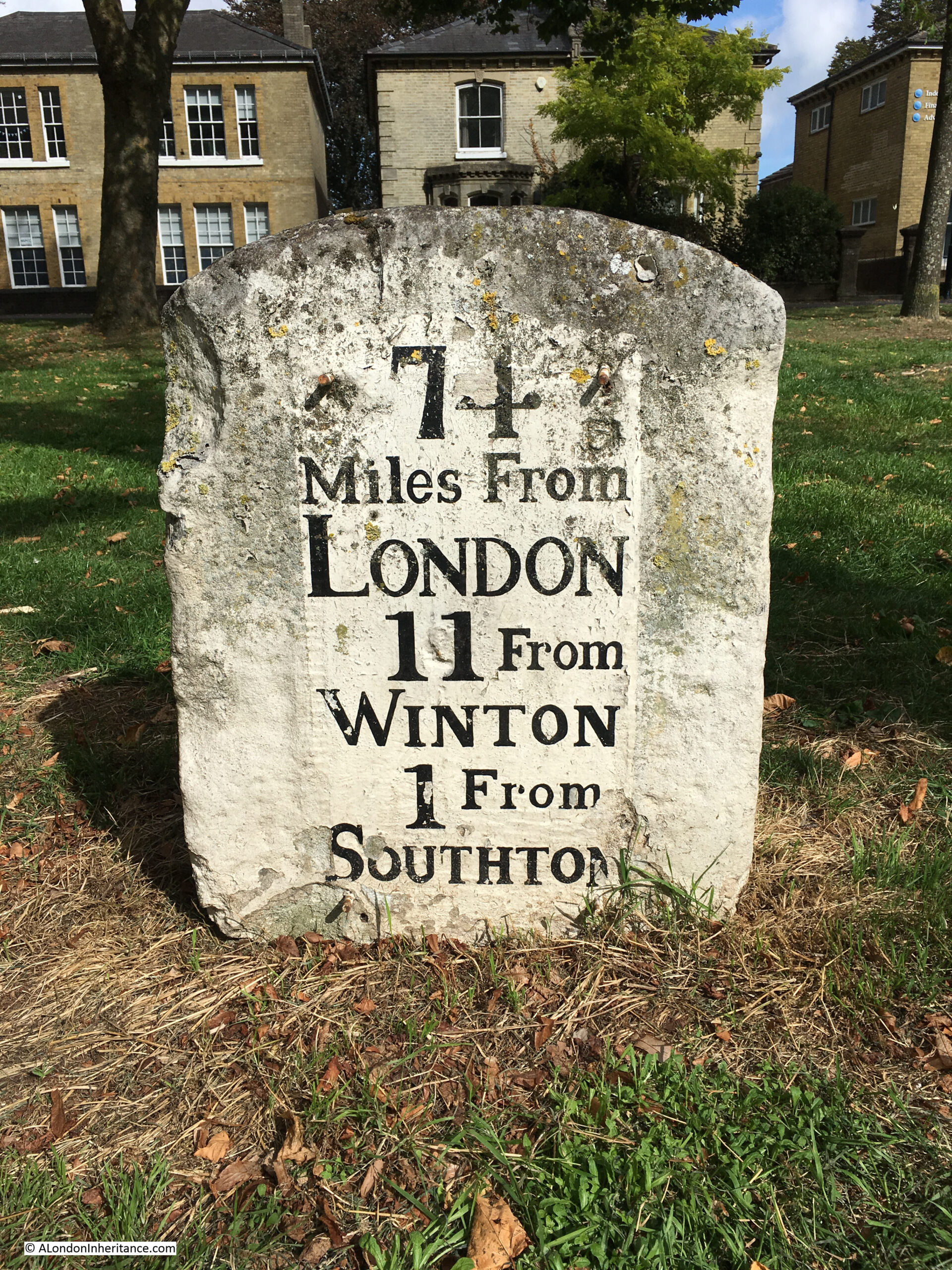

2021 – 74 Miles from London

This post started with an 18th century milestone to be found in Southampton, indicating that it is 74 Miles from London:

I have always been interested in London’s relationship with the rest of the country. Frequently, this is seen as a negative. The north / south divide, London getting the majority of available infrastructure investment, higher wages in the city etc.

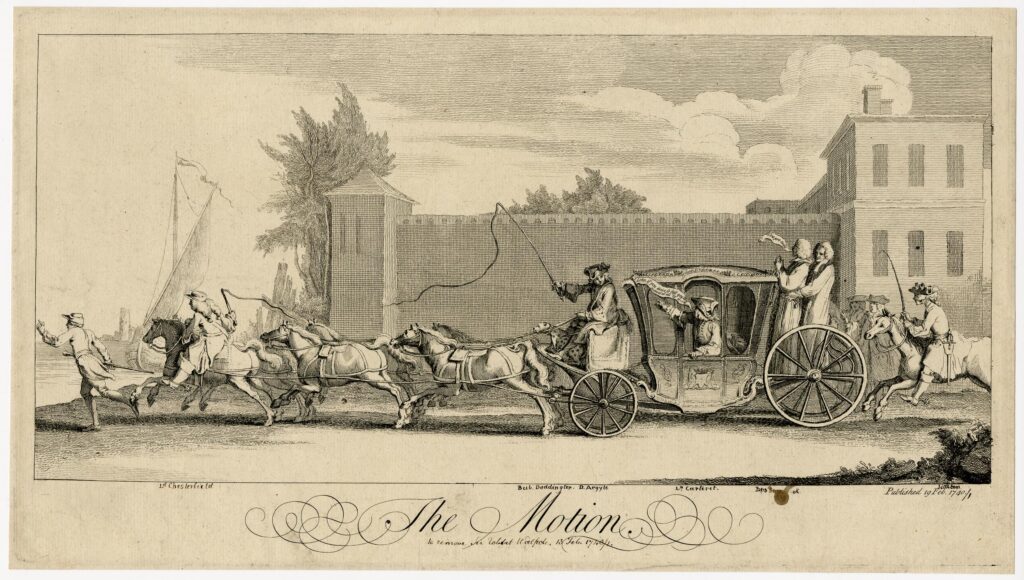

London’s central role in the country started many hundreds of years ago with the founding of the Roman City of London, located on a crossing point on the Thames, and where the new city was accessible from the sea.

Roads spread out from London, and the city became a cross roads for long distance travel. This was accentuated with the city becoming the centre for Royal and Political power, the Law and also a centre for trade and finance.

Look at a map of the country today, and the major roads that run the length and breadth of the country still start in London (A1 – London to Edinburgh, A2 – London to Dover, A3 – London to Portsmouth, A4 – London to Bath and Bristol, A5 – London to Holyhead).

Many of these major roads have been upgraded and follow new diversions, but their general routes have been the same for many hundreds of years, and a milestone is an indication of the age and importance of the route.

2021 – The Thames from Cherry Garden Stairs

The old stairs leading down to the River Thames have been a long running theme to the blog. These stairs mark a place that has been important for centuries, where access between the land and river was available.

My father took the following photo from Cherry Garden Stairs, Bermondsey, looking along the river towards the City, with the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral visible through Tower Bridge.

When the photo was taken, in 1946, the river bank was lined by warehouses, wharves and docks, with cranes along the river. A large number of lighters and barges are moored on the river, and directly in front of the camera, which would have been on the foreshore.

These stairs are very quiet today, however countless thousands of people have used these stairs to get to and from work, to take a Waterman’s boat, to leave London, to arrive in London, or to flee from the consequences of a criminal act, or to escape persecution.

2022 – Tunnelling the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway

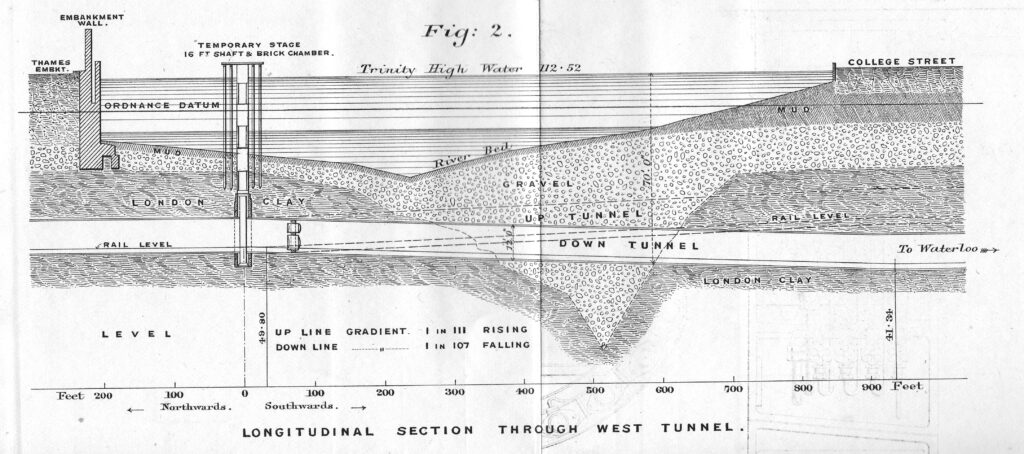

The route of the Baker Street and Waterloo railway ran beneath the Baker Street Station of the Metropolitan District Railway, by Regent’s Park and Crescent Gardens into Portland Place, through Langham Place to Oxford Circus (where the tunnels pass over those of the Central Line with a clearance of only 6 inches at one point), down Regent Street to Piccadilly Circus, along Haymarket and Cockspur Street to Charing Cross, along Northumberland Avenue, then under the Thames to College Street, Vine Street and Waterloo Station.

The majority of the tunnel went through London Clay and was a relatively easy construction project, however there was a challenge where the tunnel went underneath the Thames.

The above diagram shows the route under the Thames of the Baker Street and Waterloo railway, a depression in the London Clay and short distance of gravel through which the tunnel would need to run.

The tunnel passes under the river as seen in the following photo, and the blog post tells a story of the challenges of digging the tunnel in very difficult conditions.

2022 – The First East Ham Fire Station and Fire Brigade

My Great Grandfather was born in 1854, and as a young man, he went to sea and travelled the world.

He became a fireman in 1881, joining the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB) at Rotherhithe, south east London, later moving to West Ham in 1886 as a Fire Escape man, where he remained for ten and a half years. At the time the MFB recruited only ex seamen and naval personnel as the Brigade was run on Naval discipline with a requirement for familiarity of climbing rigging and working at heights.

In 1896 he became the Superintendent of the new East Ham Fire Station, and in 2022, I completed one of the many tasks on my to-do list by visiting the site of the Fire Station in Wakefield Street, East Ham:

I cannot find the exact year when the fire station was demolished, it was at some point after 1917, and the location is now occupied by the flats shown in the above photo, but I did find lots of references to the fire station, and the work of the crews based there. which I wrote about in the post.

2022 – Eleanor Crosses – Grantham, Stamford and Geddington

One of the many historical journeys across the country that ended in London was that taken by the funeral procession of Queen Eleanor of Castile, a remarkable 13th century woman.

The procession started from the site of her death, in Harby, Nottinghamshire. On the journey to London a cross was built at each of the places where the procession stopped overnight, and in 2022 I followed the route through Lincoln, Grantham, Stamford, Geddington, Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St. Albans, Waltham and then into Central London at Cheapside, Charing Cross and finally Westminster Abbey, where her body was buried.

Geddington has the best preserved of all the remaining Eleanor crosses, which is located in an open space at the centre of the village:

The procession arrived at Geddington on the 6th of December 1290. Geddington is a small village, and the reason for choosing the village as a stop is that a royal hunting lodge was close by, just north of the church. The lodge had been built in 1129 and was used by royal hunting parties in the local forests, indeed Edward and Eleanor had stayed at the lodge in September of 1290.

2023 – The Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green, War Memorial

One of my father’s 1980s photos was of the war memorial in Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green:

Forty years later, I went back to take a new photograph, and explore the story of the memorial and the names recorded.

The reference on the memorial to the Duke of Wellington’s Discharged And Demobilised Soldiers And Sailors Benevolent Club refers to the Duke of Wellington pub in Cyprus Street. The pub was built around 1850 as part of the development of Cyprus Street and surrounding streets.

The pub closed in 2005 and is now residential, but today still very clearly retains the features of a pub, including a pub sign.

The Most Read Post In 10 Years – London Streets In The 1980s

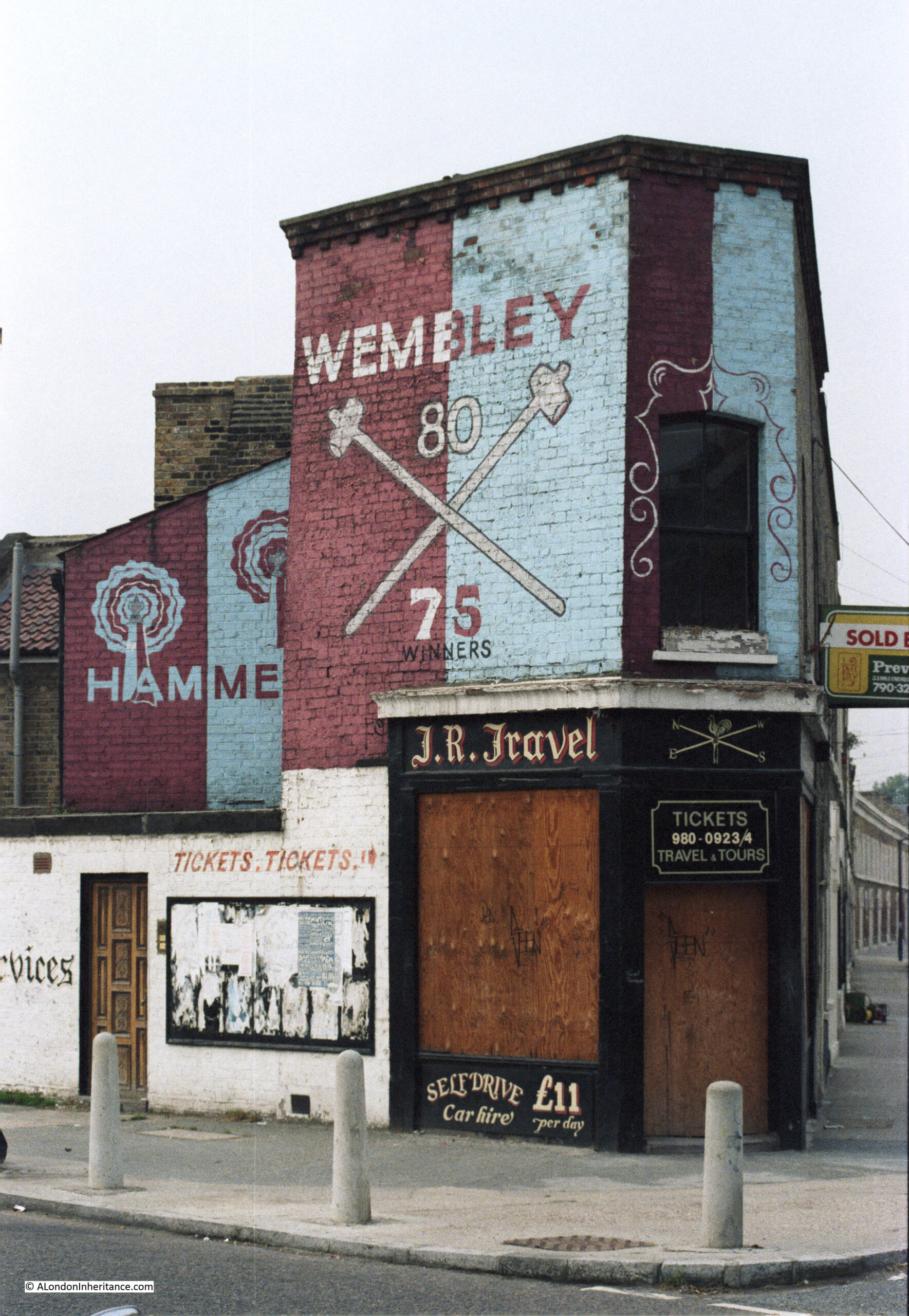

Variations of the search term “London in the 1980s” resulted in this post being the most read post on the blog in the last ten years, with people using search terms about London in the 1980s being regularly directed to the post from Google.

One of the photos featured in the post was this tribute to West Ham:

London has changed considerably since the 1980s, and will continue to change, it is the one constant throughout the whole of the city’s long history and it is fascinating to see how London has responded to so many internal and external factors over the centuries.

Thank you for reading the blog, and I hope the coming years continue to be of interest.