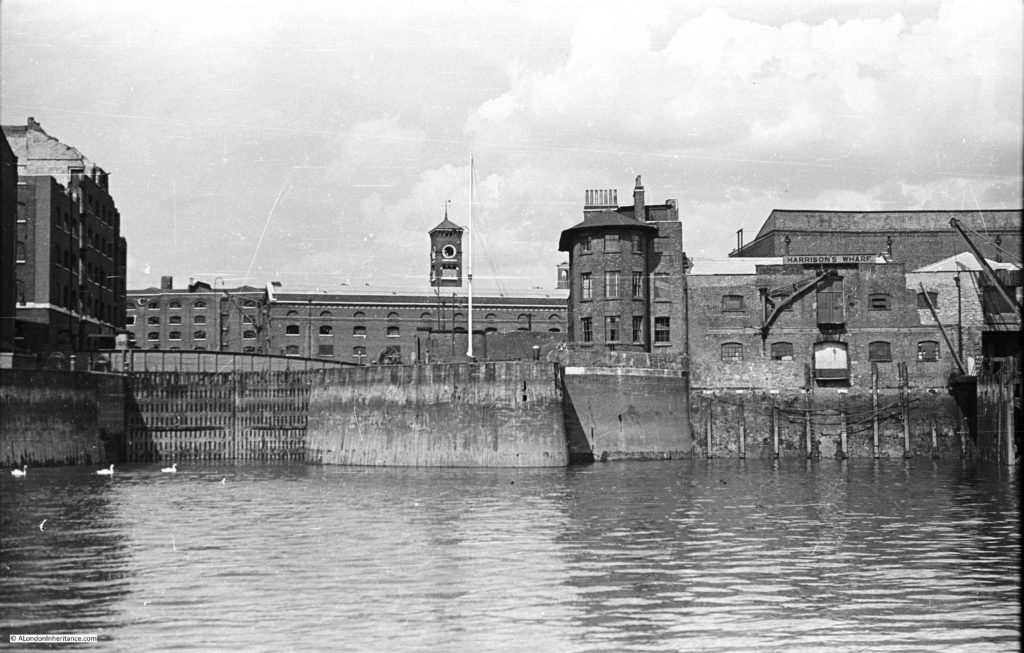

St Katharine Docks opened on the 25th October 1828. In August 1948, my father took the following photo of the dock entrance, whilst on a boat travelling from Westminster to Greenwich.

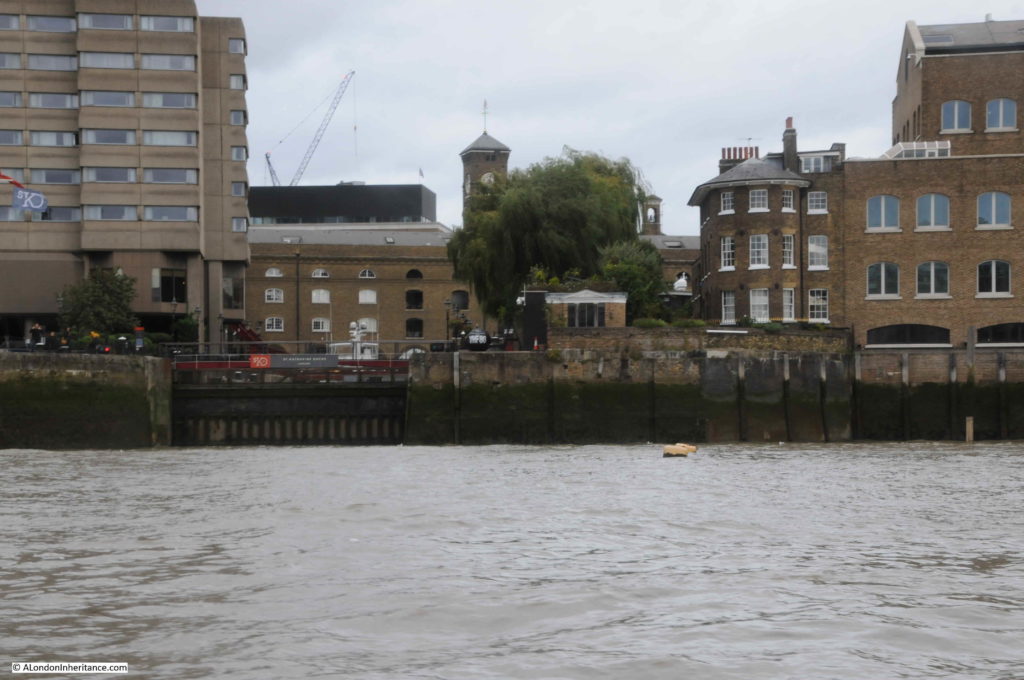

In September 2019, I took a boat onto the river, and managed to get into roughly the same position to take a photo of the same view of the dock entrance (although the weather was not as sunny as in my father’s original photo).

The Grade II listed Dock Master’s Office, with the curved frontage onto the river, still has a prominent position to the right of the dock entrance.

Part of the warehouse infrastructure can be seen in the background in both photos.

In the 1948 photo, you can just about see the original swing bridge over the entrance to St Katharine Dock. This bridge carried St Katherine Way from the east to the west of the dock.

The buildings on either side of the dock entrance have all changed. The large warehouse in the background on the right of the 1948 photo, is the warehouse seen in my father’s photo of St Katharine’s Way

The building on the left of the 2019 photo is the Tower Hotel.

A wider view (and in better weather) taken from the walk way along the south bank of the river is shown below:

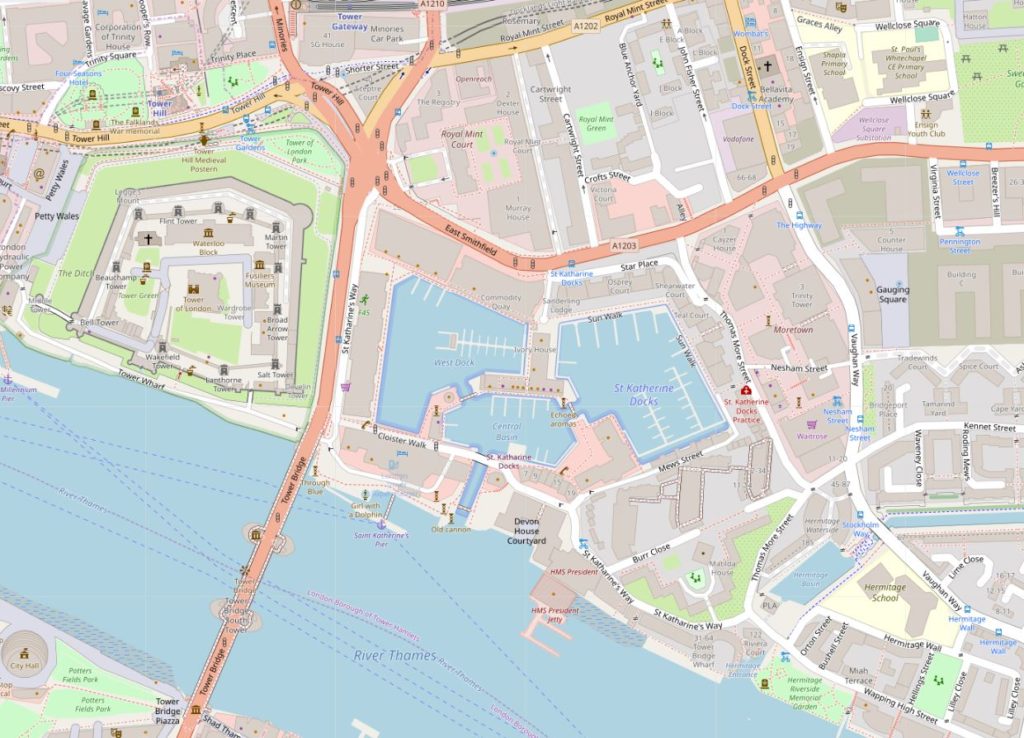

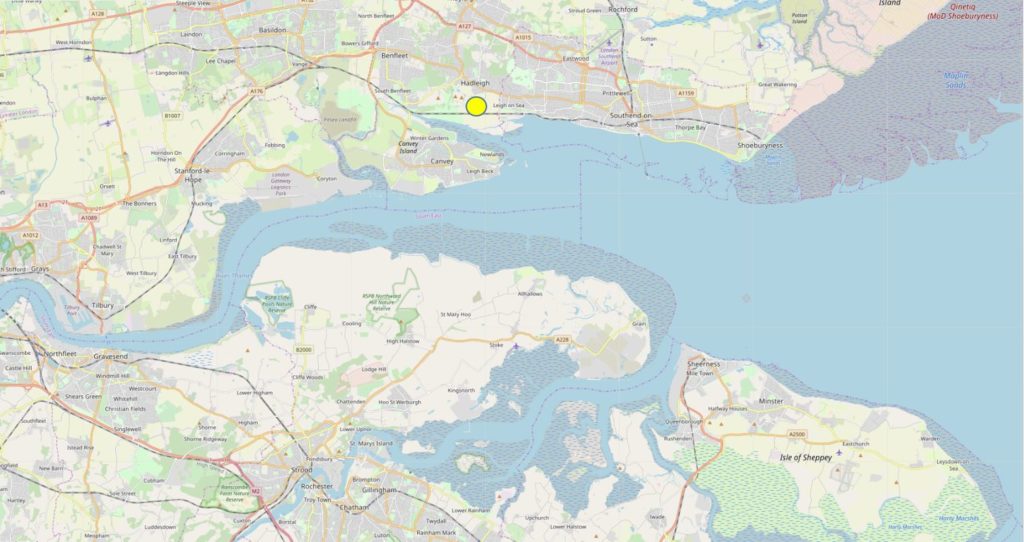

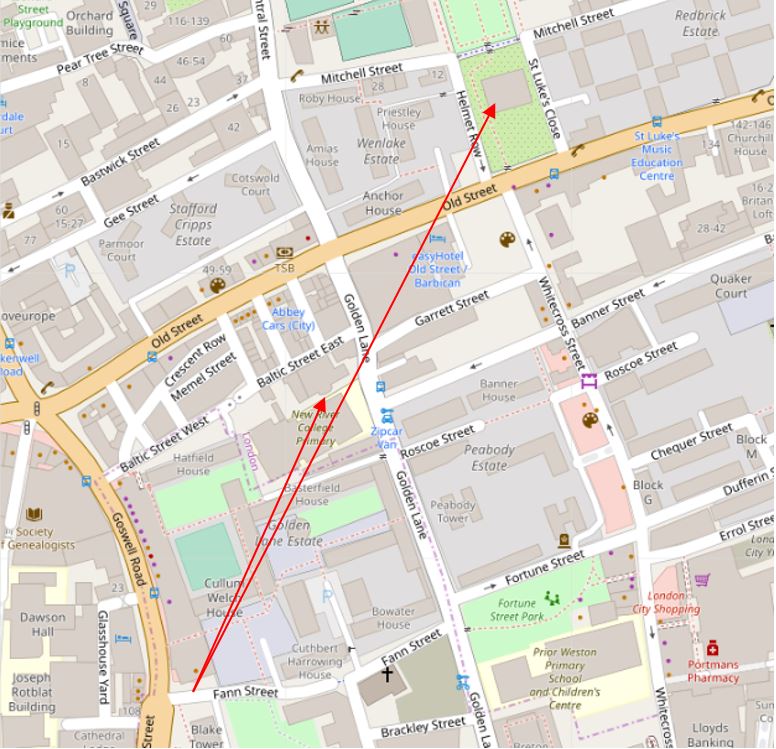

St Katharine Docks are the nearest to the City of London, of the docks constructed along the river starting in the 19th century. Occupying a relatively small area of land, and with a narrow entrance to the river, they were constructed on a historic location, immediately to the west of the Tower of London (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

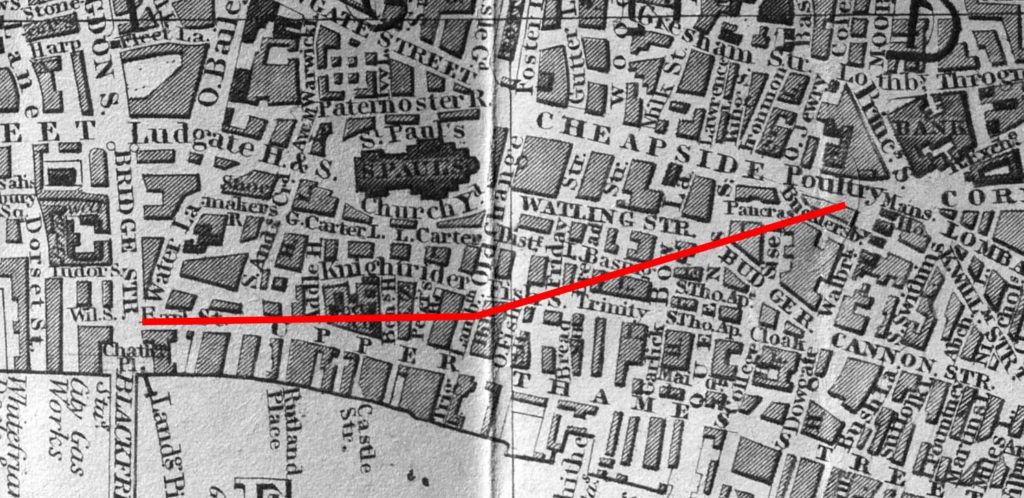

The following extract from John Rocque’s map of 1746 shows the same area as the above map. Tower bridge has yet to be built, and the area that would become St Katharine Docks is to the right of the Tower, and consists of a number of streets, church, cloisters and gardens.

The name Catherine is used for various features across Roque’s map, however I suspect this was the exception as most early maps and books reference the name spelt as Katherine, but it does highlight that the name has a long association with this specific area.

There was also a St Catherine’s Stairs shown on the map.

The area of land to be used for the new docks consisted of the foundations of St Katharine Hospital and Church, a brewery, around 1,100 houses along the streets, mainly to the north of the land.

If you look at Rocque’s map, to the right of the location of the future docks, is a narrow feature called St Catherine’s Dock, however the map strangely shows this feature not connected to the river. This dock provided a private landing place for the hospital, so in Rocque’s map it was either an error that the extension to the river was not shown, or by 1746 it had been filled in, which I doubt.

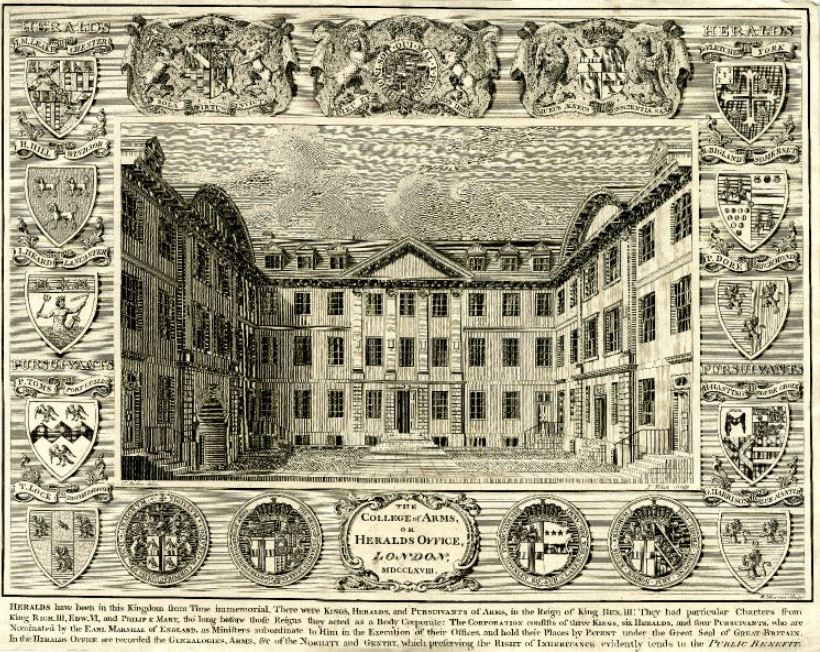

St Katharine Hospital was founded by Matilda, wife of King Stephen, on land she purchased from Holy Trinity, Aldgate.

Matilda was a fascinating character. The wife of Stephen of Blois, who was pregnant and living in Boulogne when Henry I died. Stephen raced across the channel to claim the crown in 1135, leaving Matilda in France to have her baby.

She joined him after the birth, and supported him throughout his war with another Matilda (Empress Matilda, Stephen’s cousin who also claimed the crown).

As well as raising support for Stephen from her allies in France, Matilda purchased the land, and founded the Hospital. Matilda transferred the custody of the Hospital to Holy Trinity, Aldgate, but reserved the right to choose the Master for herself, and all the Queens who would follow her.

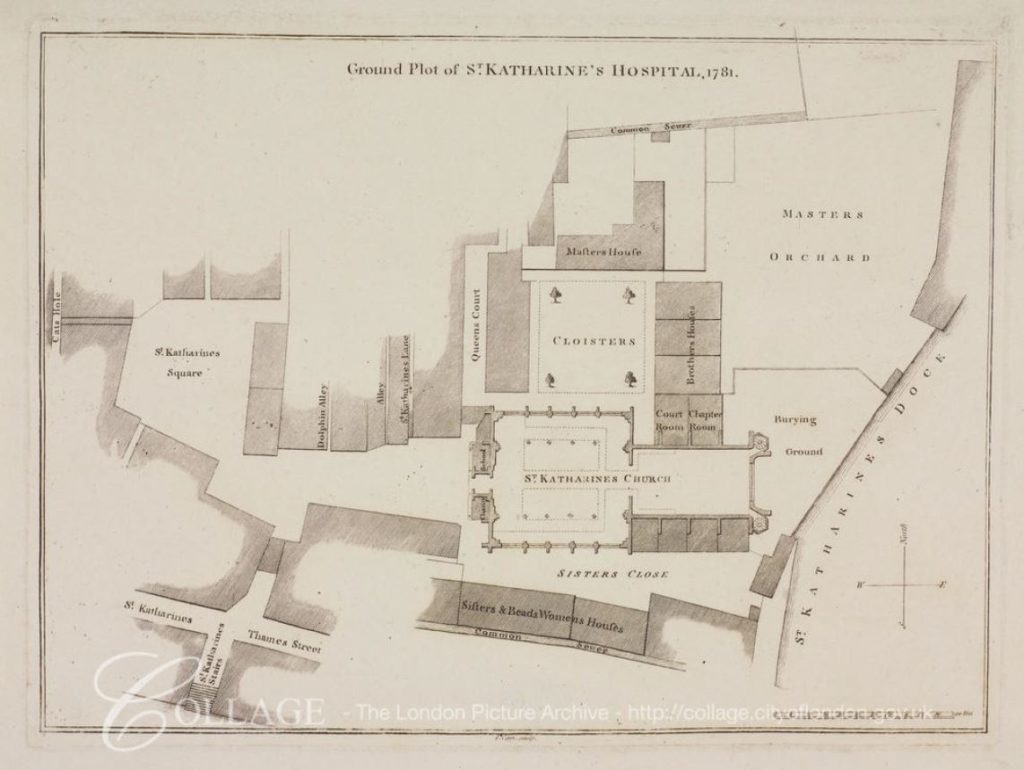

The following map from 1781 shows the Hospital in more detail to Rocque’s map, and shows the church, cloisters, houses for brothers and sisters, burying ground and orchard. The St Katharine Dock, that provided private access to the Hospital is shown on the right of the map. The River Thames is at the bottom of the map as shown by St Katherine’s Stairs on the lower left.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5412730

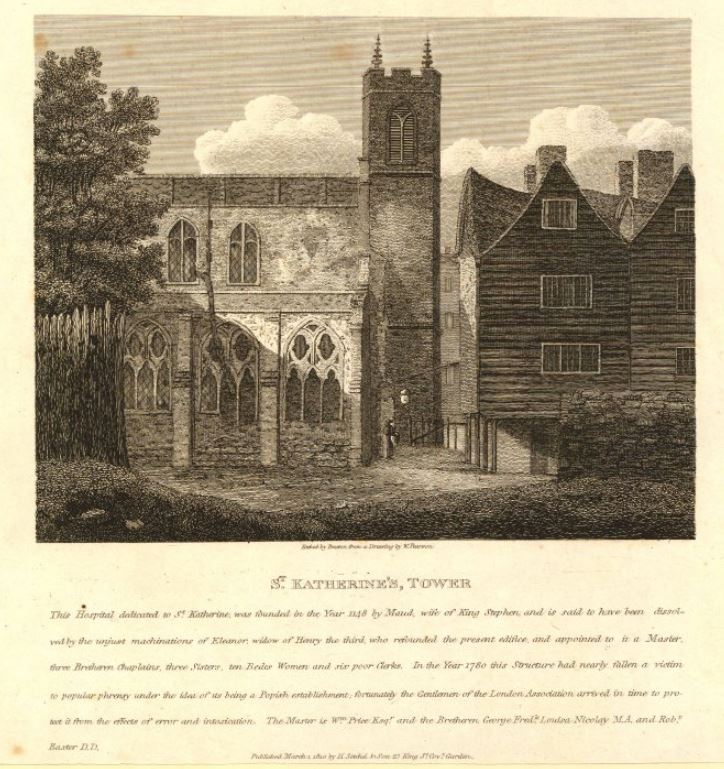

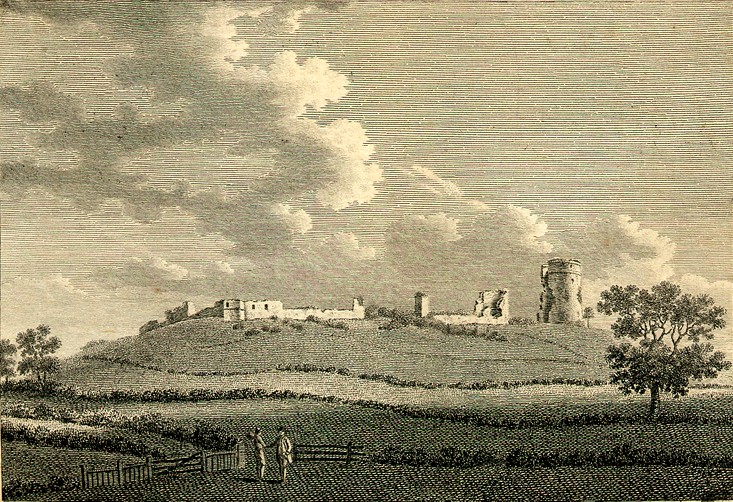

The following print from 1810, shows the church of St Katherine’s, Tower:

The text provides some background (although I suspect the author has his Matilda’s muddled, as he states Maud, wife of King Stephen, rather than Matilda. Maud was also the name applied to Empress Matilda, the other claimant to the English crown):

“This Hospital dedicated to St Katherine, was founded in the Year 1148 by Maud, wife of King Stephen and is said to have been dissolved by the unjust machinations of Eleanor, widow of Henry the third, who refounded the present edifice and appointed to it a Master, three Bretheren Chaplains, three Sisters, ten Bedes Women and six poor Clerks. In the Year 1780 this Structure had nearly fallen a victim to popular phrensy under the idea of its being a Popish establishment; fortunately the Gentlemen of the London Association arrived in time to protect it from the effects of error and intoxication.”

The problem with secondary (or much more remote) sources such as prints or books is that they often have errors and contradictory information.

Old and New London (Walter Thornbury, 1881) also states that the Hospital was dissolved and refounded by Eleanor, widow of Henry III, whilst London Churches Before The Great Fire (Wilberforce Jenkinson, 1917) states that “The Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katherine by the Tower, founded by Queen Alienore, widow of Henry II”.

What appears to have happened is that the standards of the Master and Brothers had fallen below what was expected as they were found to be “frequently inebriated”, so in 1273 Queen Eleanor refounded the Hospital and appointed a new Master and Brothers.

The brothers houses in 1781:

The Hospital survived the Reformation, probably as a result of the influence of Katharine of Aragon, who despite her divorce from Henry VIII, remained the patron of the Hospital, Anne Boleyn did not take up the role, despite this being the traditional role of the Queen.

The early 19th century was a time of considerable expansion of the docks, eastward from the City. The volume of shipping and of goods was high, and the charges levied by the dock owners had limited competition, so there was no incentive to reduce charges. Shipping volumes across the Port of London increased from 13,949 in 1794 to 23,618 in 1824.

The scheme for St Katherine Docks comprised a basin of about 1.5 acres, and two docks of around 4 acres each.

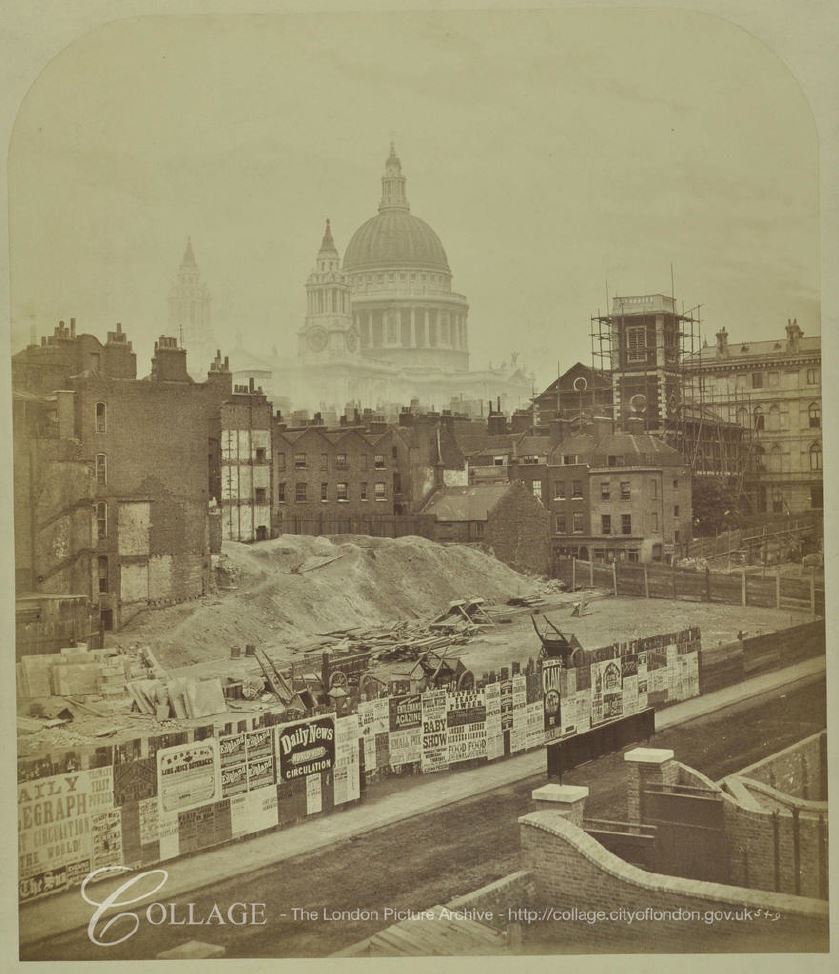

The following plan from 1825 showing the proposed St Katharine Docks is fascinating:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: q8051215

The plan shows how the new docks would overlay the existing streets and buildings, and therefore provides a means to locate where these would be across the current site. It also shows the location of the original St Katharine Dock, the narrow channel to the right of the central basin.

The plan shows that originally two entrances to the docks were planned, however only one was built.

St Katharine Docks had a rather unique design, different to the design of the London and West India Docks. in these docks, which had already been constructed, there was an area of land between the edge of the dock and the warehouses. This allowed goods to be offloaded, then sorted before moving to the correct warehouse.

With the design of St Katharine Docks, the warehouses were built almost up against the edge of the dock, with the intention that goods would be unloaded directly from ship into the warehouse, therefore making the whole process considerably more efficient. This would work well if the goods from a ship were all of the same type, but not for a mixed cargo. This design was not used again at any other London dock, which probably gives an indication that the intended efficiencies were not achieved, or that the design lacked flexibility to support mixed cargoes.

The dock entrance from the river was also of a smaller width than the other docks, thereby limiting the size of ship that could enter St Katherine Docks.

The scheme was put before Parliament in 1823, but was opposed by the Commons on the second reading. The scheme returned to parliament in 1825. The owners of the London Docks opposed the building of the new docks and attempted to demonstrate that spare capacity was available at other docks on the river, however incorrect figures put forward by the London Docks Company was shown to be wrong, and that there were indeed problems with warehousing space, and that the London Docks sometimes had 4,000 to 5,000 casks waiting on the dock side for space in the warehouses.

There were also arguments against the use of such historical land, which had been used for religious purposes for seven centuries, however the remaining Brothers were offered new accommodation near Regent’s Park, which was probably a much improved location to that near the river, which Stowe described as “tenements and homely cottages having inhabitants, English and strangers, more in number than on some city in England”, and with street names such as Dark Entry, Cat’s Hole, Shovel Alley and Pillory Lane.

The new buildings by Regents Park for the Brothers were designed by Ambrose Poynter in a Gothic style, much to the frustration of Nash, who saw the buildings as a Gothic intrusion into his Georgian terraces.

The bill, as approved by Parliament, had clauses added to protect and refund the landlords of the properties, however those who were renting the houses in the streets that would soon disappear had to fend for themselves, and find new accommodation in the City (reading the proceedings of the bill, it is remarkable how the process appears to be the same as today, and perhaps also the focus on land owners rights, rather than those only able to rent a property).

The last service in the church took place on the 30th October 1825, with construction starting in 1827, the foundation stone being laid in May of that year.

The soil excavated from the docks was transported west along the river and used to fill in the old reservoirs of the Chelsea water works, and along the southern parts of Pimlico.

Delays to completion of the docks were caused by an exceptionally high tide on the 31st October 1827, which flooded part of the dock workings – newspaper reports tell of Londoners watching the inundation from the edge of the construction site.

The docks were completed and officially opened on the 25th October 1828.

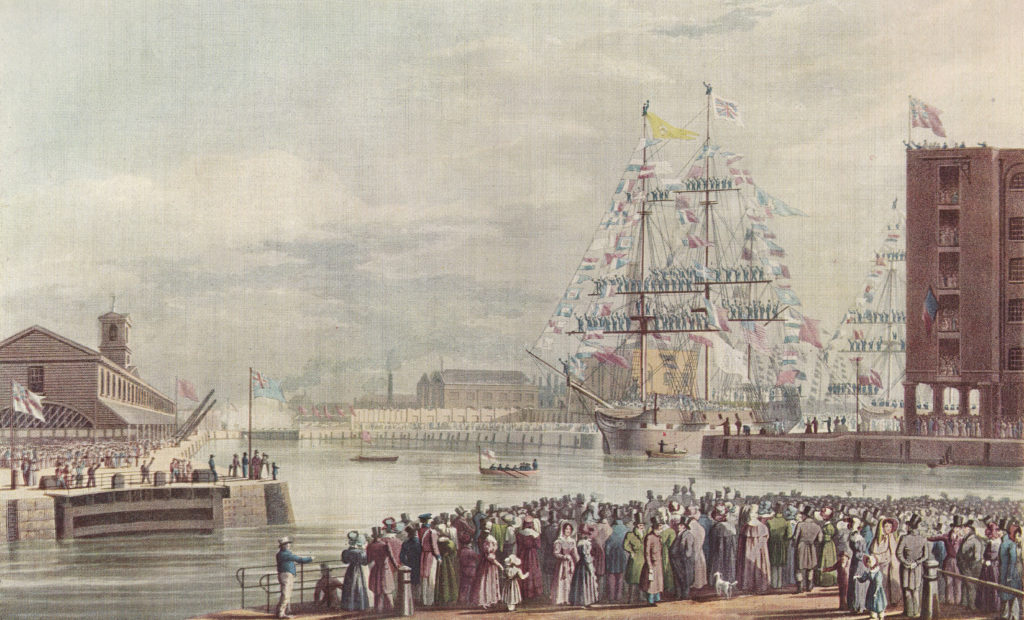

The following painting shows the first ships entering St Katharine Docks during the opening ceremony.

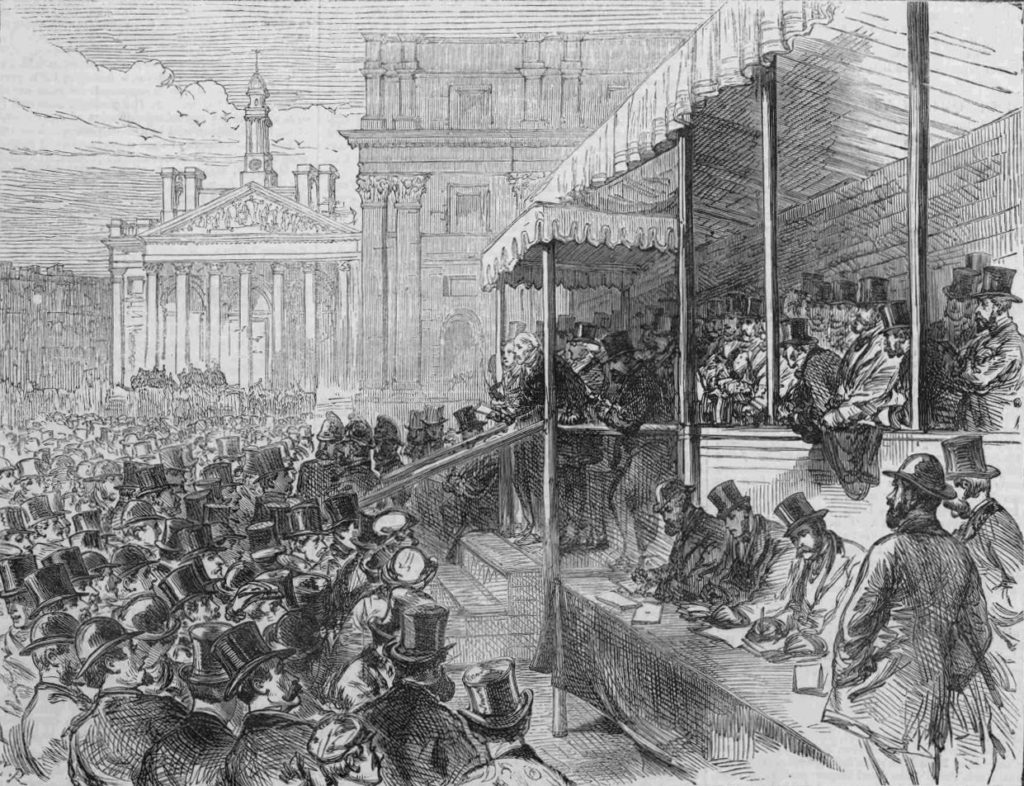

The opening ceremony was reported in the press as a great celebration – from Bell’s Weekly Messenger on the 27th October 1828

“The interesting ceremony of opening the St Katharine Docks took place on Saturday afternoon, and was witnessed by between 18,000 and 20,000 persons. Such was the excellence of the arrangements made, that not a single accident occurred.

By one o’clock in the day, the wharfs and ranges of warehouses presented a most brilliant and animated scene, being filled by highly respectable individuals. Four bands of music were stationed at different positions, and enlivened the scene by playing national and other airs. The ships, nine in number, destined to enter the Docks, were off the entrance dressed out in the colours of all nations, and nearly every vessel in the vicinity of the Docks hoisted her colours, so what with the numerous banners flying in all directions, and the fineness of the day, a more interesting sight has seldom been witnessed. On the eastern dock wharf was stationed a small pack of artillery, which was discharged repeatedly during the entrance of the vessels into the Docks. At about a quarter to two o’clock the tide had risen sufficiently high to permit the commencement of the ceremony.

The Dock gates were opened, and the Eliza, a fine East India trader, in ballast, entered amid the most deafening applause. The bands struck up ‘God save the King’. The yards were manned, and the deck was crowded by visitors. She entered majestically and was greeted loudly. She is bound for Madras, and waits a cargo at the Docks. Next followed the Mary, laden with goods from the Cape of Good Hope; she also was greeted warmly. The Catherine, Prince Regent and five other vessels followed, all dressed out, and were loudly cheered. the latter are in the Baltic trade. The ceremony having been concluded, the large mass of the visitors departed – those having blue tickets however, passed up into the second floor of the warehouses, marked C, and there partook of a grand collation provided for the occasion.

Success to the St Katharine Docks was drank in bumpers from every mouth, and the day passed off without the occurrence of any untoward event to damp the spirits of the numerous company.”

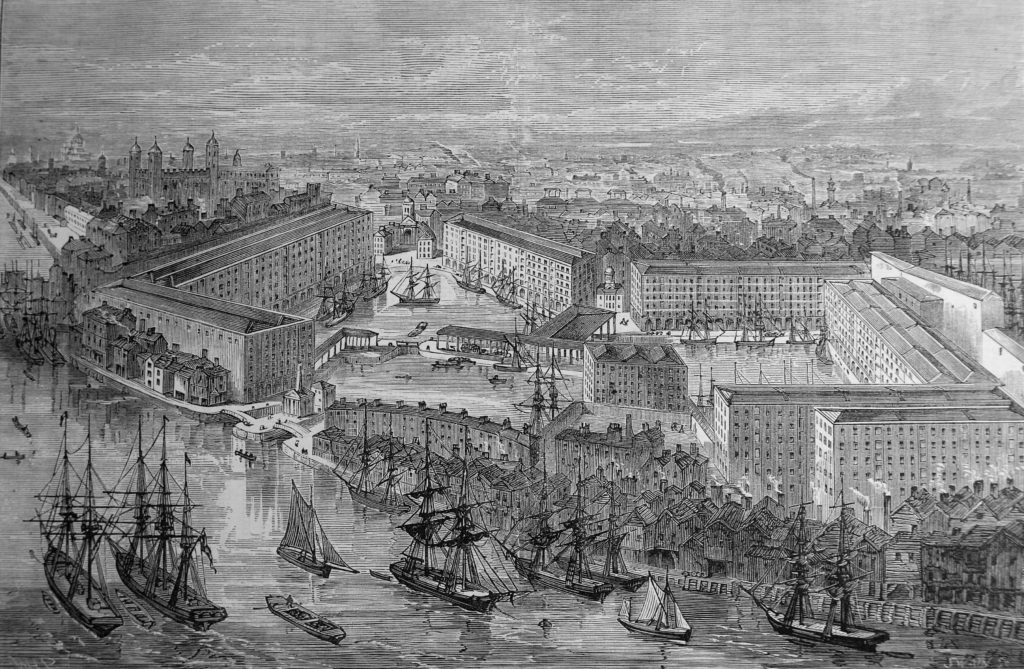

The docks as they appeared in full operation:

The business opportunities offered by the new Docks were quickly recognised by the businesses in the immediate vicinity, as illustrated by the following newspaper advert:

“Lot 2. A substantial brick-built Free Public-house, the Camel, No 107 Minories, in view of the entrance of the St Katharine Docks, capable of doing a good trade in the spirit and tavern department, from its approximation to the Docks. Lease 19 years, at a moderate rent.”

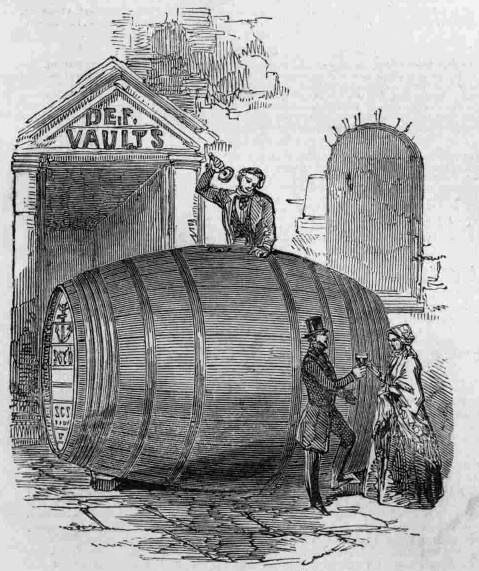

A rather unusual import occurred in December 1848 when an immense cask of Port Wine was delivered from Oporto by the ship Pezo da Regoa. It held around 620 gallons with a value of £650 – a considerable sum in 1848. The justification for the large cask, was that wine develops a “high vinous character more fully in a large bulk, than it is possible to do in the casks (little more than one-sixth in size usually employed for transmission to this country”.

The giant cask:

St Katharine Docks were reasonably successful, although perhaps not as good as expected. Returns to investors averaged between 2.75% and 5% in the years up to 1864, when St Katharine Docks amalgamated with the nearby London Docks.

One of the limitations to the success of St Katherine Docks was the narrow entrance from the Thames which limited the size of ships able to enter.

The docks were bombed during the war, and never recovered after the war, becoming the first of the London docks to close, in 1968.

Unlike the docks further east, St Katharine Docks were not left derelict for too long, however many of the original warehouses were demolished to make way for new buildings in the 1970s, and the dock itself became a mariner.

I suspect it was the proximity to the City that resulted in the rapid reuse of the site. The docks further east, and on the Isle of Dogs were too remote from the City, and also St Katharine Docks was a much smaller parcel of land than the other locations.

I went for a walk around St Katharine Docks at the end of August, when the weather was far better than on the day i was on the river. There is now a foot bridge over the dock entrance, close to the river. This is the view looking up towards the basin, with one of the few remaining buildings in the background, along with the clock tower seen in my father’s 1948 photo.

I have taken loads of photos around St Katharine Docks over the years. The majority I have yet to find and scan, however this is a photo from 1981 from above the dock entrance showing a similar view.

On the day of my visit, it was the start of the Round the World Clipper Race, so the docks were looking more colourful than usual.

This is the view over the eastern dock. All the original warehouse buildings have been demolished, to be replaced with new apartment buildings.

The Clipper yachts adding a splash of colour in the central basin:

At the time of writing, the Clipper yachts have left Uruguay and are a short distance into their crossing of the South Atlantic Ocean, on their way to Cape Town, South Africa. A nice link with the past, when ships arriving at, or leaving St Katharine Docks would travel to all regions of the world.

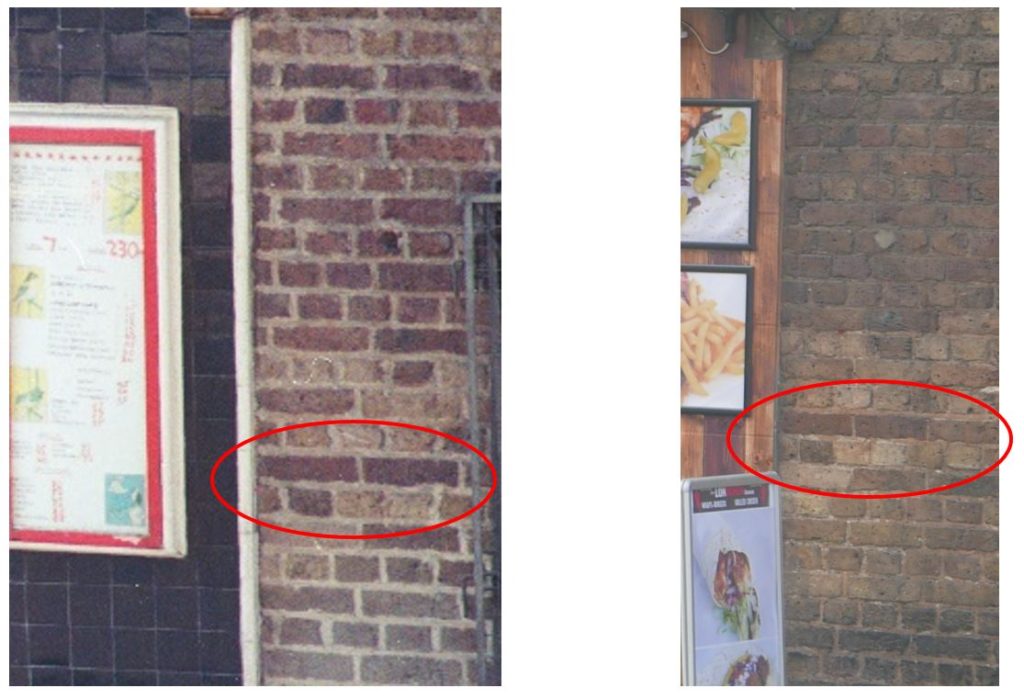

The following photo is of the walkway alongside the main remaining warehouse.

The photo illustrates the design, only used at St Katharine Docks, where the warehouse was built very close to the edge of the dock. There was no space for unloading from the ship and sorting on the quayside, before moving to the correct warehouse. At St Katharine Dock, the intention was to move cargo more efficiently directly from ship to warehouse.

The photo also shows how St Katharine Docks have now been transformed into a popular food and drink destination, with restaurants lining the ground floors of the old warehouse and some of the buildings that have replaced many of the original buildings.

Looking back over the central basin. The entrance to the dock is on the right:

The walkway across from the central basin to the edge of the western dock:

The western dock, showing how St Katharine Docks are now used as a marina.

The photo below is another of my 1981 photos of St Katharine Docks. This is on the north bank of the western dock. In the above photo, it is where the new buildings along the right of the dock are located.

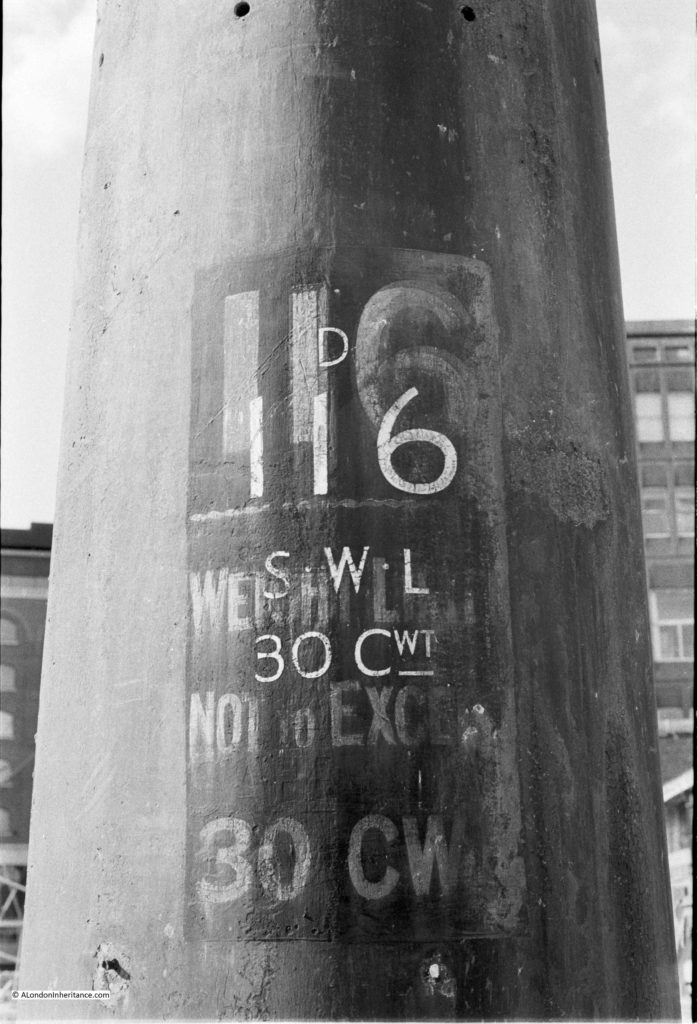

This was at a time when parts of the dock were still yet to be developed, and you could drive into and park directly alongside the docks. The cast iron pillars are all that was left of the warehouse that ran alongside this part of the docks. These all appear to have been lost as part of the redevelopment.

Detail from one of the pillars:

The original stone of the dock side walls survives:

Mayhew, in London Labour and the London Poor provided some interesting statistics which give some insight into employment at St Katharine Docks.

St Katharine Docks employ a ticket system for the employment of workers. The docks would not employ casual workers, only workers who had previously been recommended to the Company and were seen to be of good character. The Company would allocate a ticket to the worker, allowing them to be employed as a preferable ticket labourer.

Despite having a ticket, a worker would not have a guaranteed level of work, as this was dependent on the number of ships, and volume of goods to be moved.

The base level of employment at the docks was 35 officers, 105 clerks and apprentices, 135 markers, samplers and foreman, 250 permanent labourers, 150 preferable ticket labourers, proportionate to the work to be done.

The number of labourers needed could fluctuate dramatically. In 1860, the number of labourers employed at the docks on any one day ranged from 515 to 1,713, so a range of 1,200 a day, in the need for labourers.

Mayhew commented that the ticket system at St Katherine Docks did appear to result in a workforce that “have a more decent look, but seem to be better behaved than any other dock-labourers I have yet seen”.

Despite the ticket system and the workforce “having a more decent look”, the daily fluctuation in the number of workers needed would result in many hundreds not receiving a wage for the day, whilst for those in work, the newspaper advert mentioned earlier told of the pubs that lined up. close to the dock entrance, ready to take the wages of the worker before he reached home.

Again, I have only just scratched the surface of such an interesting and historic London location. History dating back to the 12th century, with a religious function for 700 years until religion was replaced by commerce with the building of the docks in the early 19th century.

A subject to return to, when I have found more of my photos of the site over the last few decades.