The end of February marks the time when I first started the blog back in 2014, so this February is the completion of 9 years, a point I did not expect to get anywhere near.

The aim of the blog has always been the same, to provide an incentive to locate, and a means of recording, my father’s photos of London, and occasionally further afield, and to act as an incentive to explore somewhere that I had probably taken for granted for so many years.

What has been wonderful is that so many people regularly read what started out as a rather selfish endeavour, and I would really like to thank the thousands who have subscribed to the blog. It goes out every Sunday to a subscriber list I would not have considered possible when I started.

For me, the blog has also acted rather like a diary. I have never had much luck keeping a diary, with various attempts usually ending in mid January, however looking back on old blog posts, the text and photos act as a reminder of what was happening in the wider world at the time, and what I was doing.

So, for today’s post, a review of the blog from the end of February 2022 to 2023.

Walks

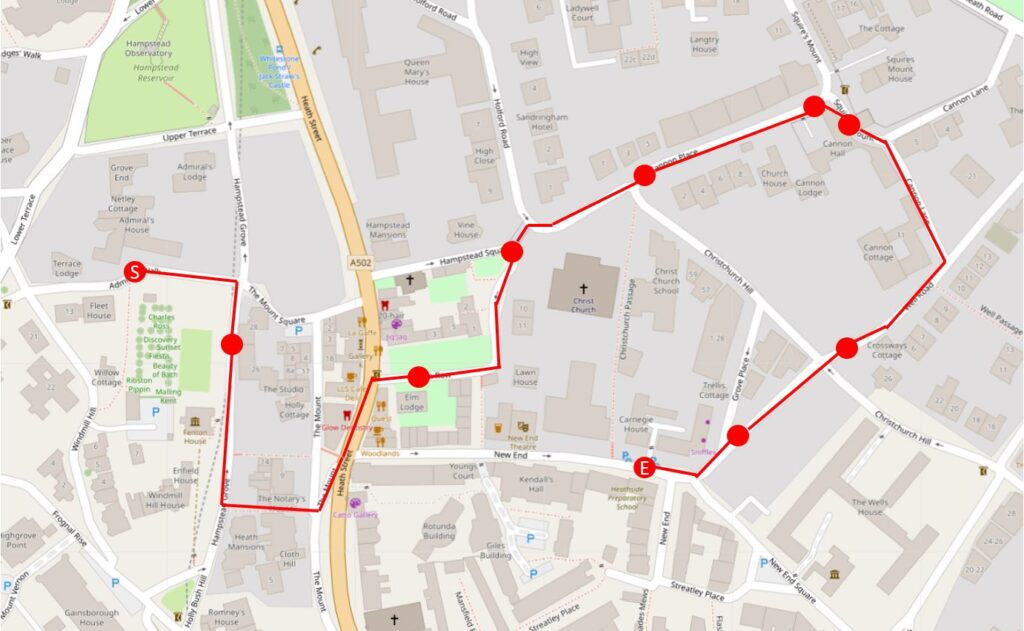

Thank you to everyone who came on one of my walks last year. Not only is it brilliant to meet readers, and take the blog posts out into the streets, the money from ticket sales has been a real help with covering the costs of the blog.

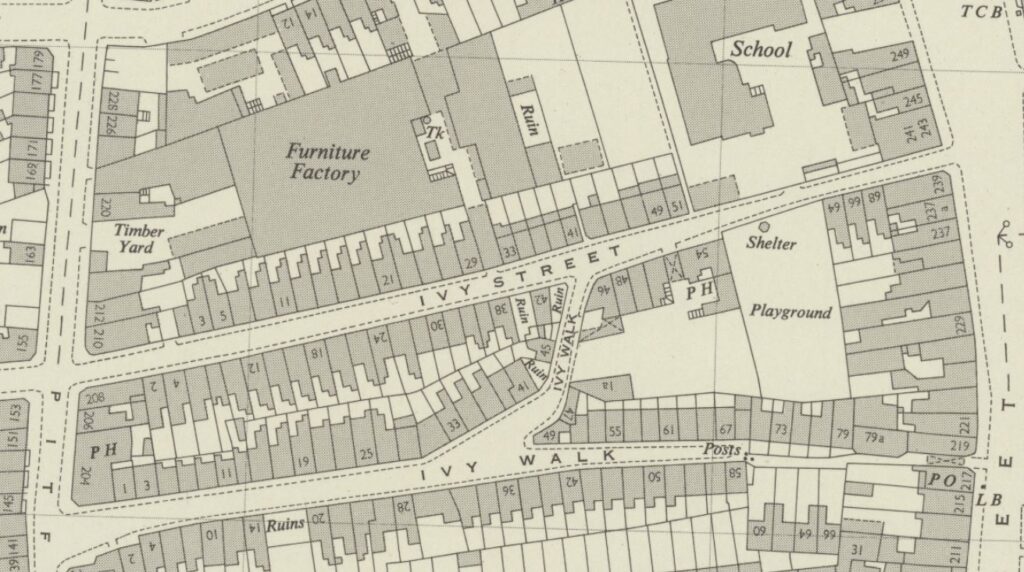

I am planning to add some new walks for 2023, currently working on Limehouse, Bermondsey and / or Clerkenwell, and I will be providing details of these and my existing walks in a future blog post.

I put them on Eventbrite first, so for early notification, give my Eventbrite account a follow here.

London Institutions at Risk

As usual, change is continuous in London, and two London institutions closed during the year.

Simpson’s Tavern in Ball Court in the City – the oldest chophouse in London closed after they were locked out by their landlord.

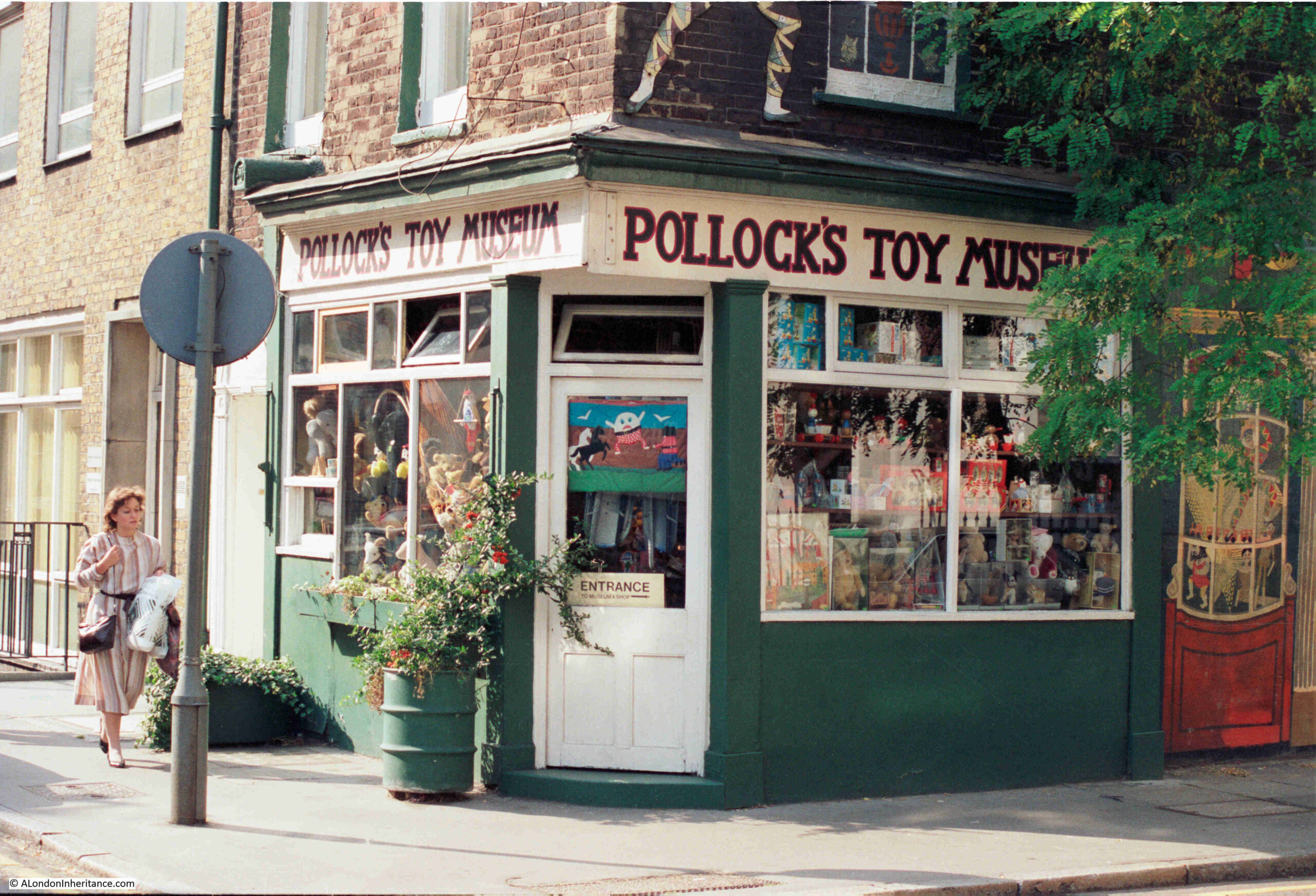

Pollock’s Toy Museum in Scala Street also closed due to a change in ownership of the building (read their statement here).

My father had taken a couple of photos of Pollock’s Toy Museum in the 1980s:

And it was on my long list of potential posts.

Hopefully, a new location will be found for the museum.

Whilst change is inevitable, and essential as change is what has made London what it is, the loss of small, unique institutions, and the loss of local character risks turning the city into a place where all the streets are the same.

My greatest concern for London is not so much change, but the “blandification” of the city, where there is no unique local character, no small, unique shops and institutions, streets lined with the same architecture and the same major brands.

No doubt the coming year will throw up more challenges, and it will be interesting to see what happens with the planned redevelopment of the old London Weekend Television Studios on the South Bank and of much of Liverpool Street Station.

Now for a quick run through of the year with a sample of the posts from each month.

February 2022

I have many themes when taking photos of London, one of which is taking photos of the street news stands across London. I have been taking photos of these for years and included in the last few year reviews.

They provide a reminder of significant events, and if the last few years is anything to go by, the news seems to keep coming thick and fast.

I also wonder how long these will be a feature of London’s streets. As well as telephone boxes, they are part of an older technology, where most people now probably get their news from the Internet.

The days of everyone on a train or underground train reading the evening newspaper on their way home are long gone. The mobile phone is now the entertainment device of choice.

The Evening Standard is the one remaining evening newspaper in London. The Evening News has been off the streets for decades, and you originally had to buy these evening papers, where now the Evening Standard is free, trying to use advertising as a way to generate revenue.

At the end of February 2022, the news of Putin’s invasion of Kyiv was across the streets of London:

March 2022

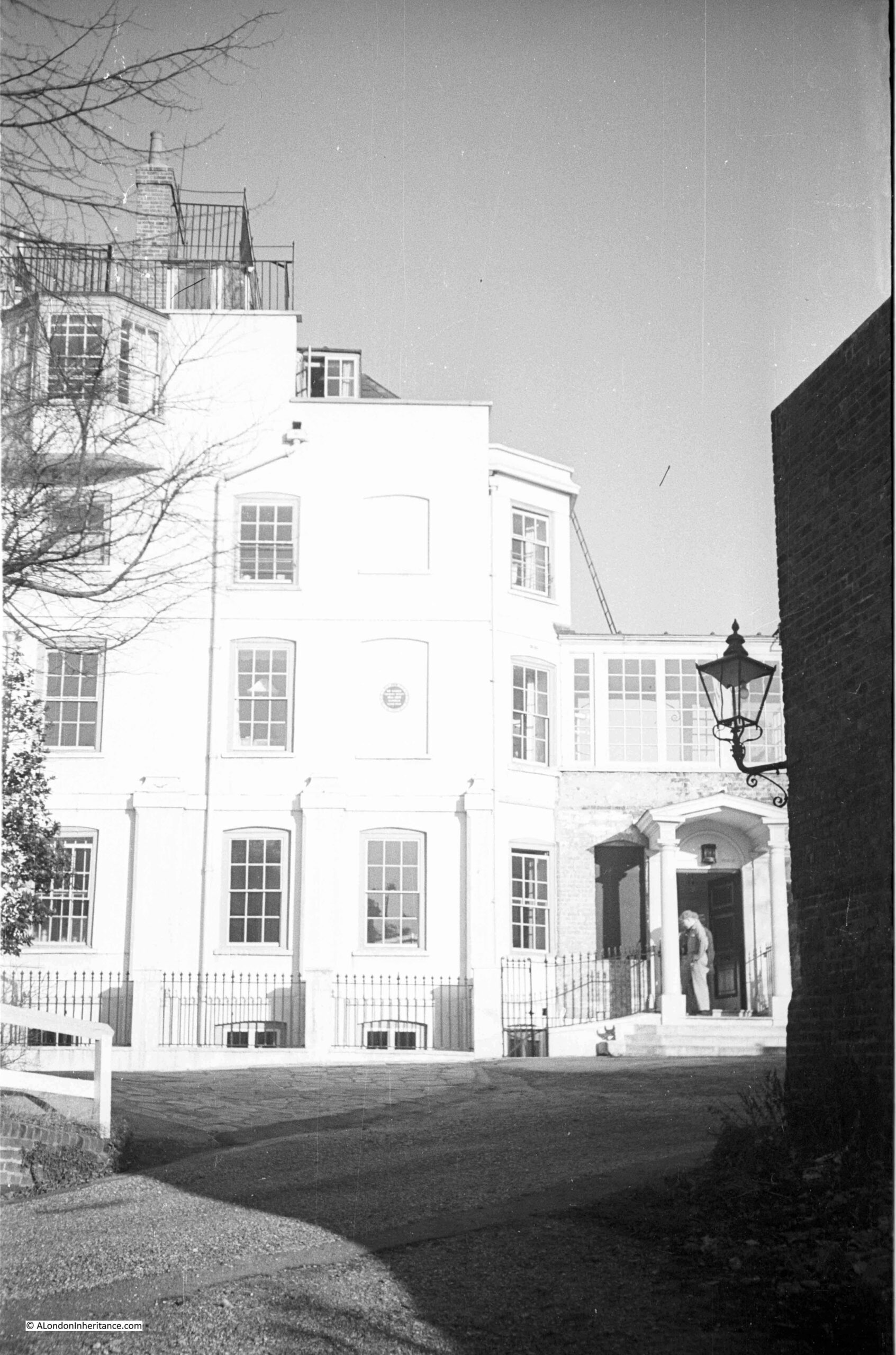

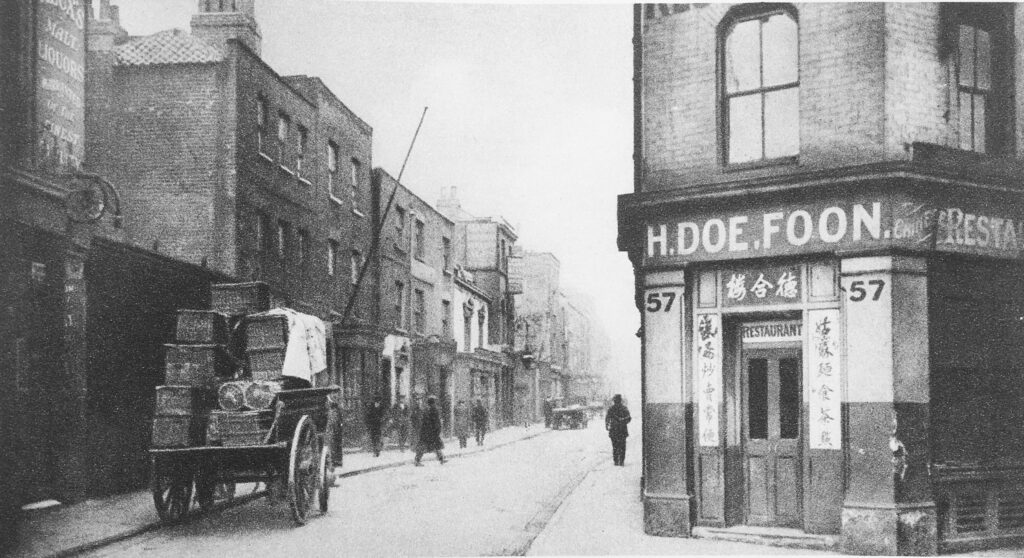

In March 2022, I went to find the site of the following photo of Pennyfields, Poplar, from the 1920’s publication “Wonderful London”:

The photo is titled “Gloom and Grime in the East End: Chinatown”, and has the following description: “A view of Pennyfields, which runs from West India Dock Road to Poplar High Street. There is a Chinese restaurant on the corner. A few Chinese and European clothes are all that are to be seen in the daytime”. The location is very different now.

In March I also completed the New River Walk, following the route of the original New River, which still carries water from Hertfordshire to provide drinking water for London.

The walk included the stretch where the New Rover is carried over the M25:

April 2022

April saw another visit to Poplar to find the site of the following photo “Welcome to the Isle of Dogs” in Prestons Road:

In April, the Evening Standard was warning that “Shoppers Turn Off The Spending Taps”, and the article on the right of the front page advised that there was “No question of Boris quitting over parties”:

May 2022

In May I was in Greenwich to find “The Sad Fate of Two Greenwich Murals”. One has been lost, however the “Changing the Picture”, which was created for the El Salvador Solidarity Campaign in 1985 is still there, but looking very much faded from the vibrant colours in my father’s photo from the time the mural was completed:

May also saw significant resumption in air travel after the previous two years of lockdown, however this resulted in the almost predictable headlines about airport travel chaos:

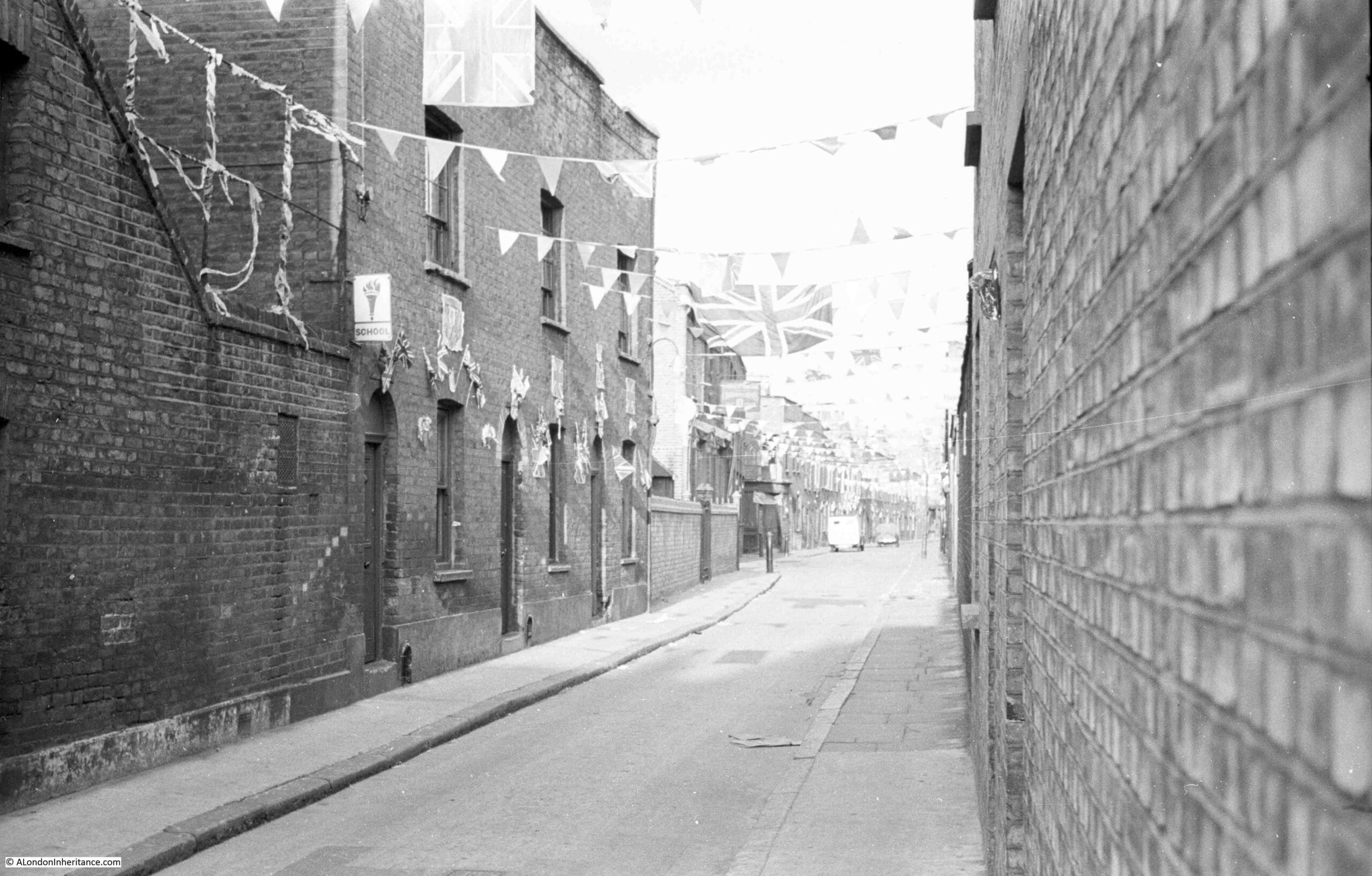

June 2022

In June, I was fortunate to get access to see the Westminster School Gateway, which my father had photographed in 1949:

The Westminster School Gateway is a historic feature of the school for two main reasons. The age and purpose of the gateway, and the inscriptions of pupil names that cover almost all the stones of which the gateway has been built.

In June I also had a walk along part of the Greenwich Peninsula, another area of London undergoing significant change, and the following 1980s photo is from my post Lovells Wharf and Enderby House, Greenwich Peninsula:

The 21st of June was the first day of the country wide rail strikes, which coincided with a strike on the London Underground. I was in London on the day, and the following photo shows part of the closed platforms at Waterloo Station:

Union members outside Waterloo Station:

Closed underground station:

The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee was also celebrated in early June, as reported in the Evening Standard:

The Evening Standard reported that Cabinet Minister Sajid Javid was telling rail unions to “Grow Up And Drop Rail Strikes Now”:

And the Standard also reported that the Government’s Rwanda plans were hit by “Fresh Disarray”:

The Evening Standard on the 21st of June reported that London was in lockdown 2.0 due to the rail strikes, and that “Boris Braces Britain For Months of Misery as RMT Pledges More Action”:

July 2022

In July I was back to a location I have featured in a couple of previous posts – Pickle Herring Street, but this time to visit Pickle Herring Stairs, one of the old stairs down to the river foreshore which have been lost in redevelopment of the area:

And despite earlier assurances in the Evening Standard, Boris Johnson had resigned and there was now a race for No. 10:

And “Truss and Rishi Lock Horns As Tory Race Hots Up”:

And Chelsea probably made a good decision:

August 2022

In August I went to find the site of an old cemetery which had been cleared as part of the construction of the District Railway, in my post “Cloak Lane, St John the Baptist, the Walbrook and the Circle Line”:

The summer of 2022 was exceptionally dry, and London’s parks and open spaces were not looking that green. In August I took the following photo in Greenwich showing very little green grass across the park:

September 2022

In September I went to East Ham where my Great Grandfather lived for a few years.

He became a fireman in 1881, joining the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (MFB) at Rotherhithe, south east London, later moving to West Ham in 1886 as a Fire Escape man, where he remained for ten and a half years. At the time the MFB recruited only ex seamen and naval personnel as the Brigade was run on Naval discipline with a requirement for familiarity of climbing rigging and working at heights.

In 1896 he became the Superintendent of the new East Ham Fire Station, and the following photo shows the site of the Fire Station in Wakefield Street, East Ham:

The Queen died on the 8th of September, and the Evening Standard reported on her return to London:

Continuing a tradition that I think started with the death of Princess Diana, people left masses of flowers to mark the death of the Queen. An area had been set aside for this in Green Park, and I went to take some photos:

There were also people camped out along the Mall in order to get prime position to see the funeral procession:

And the queue to see the Queen’s coffin stretched far along the south bank of the Thames. View by Lambeth Bridge:

South Bank:

Bankside:

October 2022

In October I went to find where my father worked for the London Electricity Board in the late 1940s and early 1950s in Pratt Street, Camden, where he had taken a series of photos looking at the view from the roof of the building:

In October I also went for a wonderful walk along the Broomway, off Foulness in Essex, said to be one of the country’s most dangerous footpaths. The London connection is that this could have been the site of London’s Third Airport in the early 1970s.

And in October, the Evening Standard was reporting that Liz Truss, who had won the Tory leadership election, was telling the Tories that she would “Get Us Through The Tempest”:

The war in Ukraine had largely disappeared from the headlines, however this headline brought back memories of the Cold War:

November 2022

In November, I wrote about a project that I would not have done if I had not been writing the blog – we followed the route of the 13th century funeral procession of Eleanor of Castile, from Harby in Lincolnshire where she had died, to her final resting place in Westminster Abbey.

It was a really fascinating journey, and one I would not have done if it was not for the blog. The following photo from the post Eleanor Crosses – Grantham, Stamford and Geddington, shows the best preserved of the crosses in Geddington:

Whilst in London there was the threat of rail strikes for Christmas:

December 2022

The BBC’s Ghost Story for Christmas was part of my childhood, with the M.R. James stories being a theme of both TV programmes and reading. In December I went to Eton Wick Chapel near Windsor to find his rather modest grave:

And also in December I went on my annual visit to walk around the construction site for HS2 in Euston:

There seems to be considerable interest in HS2 and Euston as it is one my most read annual posts. It also seems to be a rather marmite project – it is either the best project to free up capacity on the existing rail network between London and Birmingham and improve connectivity to the north, or a waste of a vast amount of money.

It will be interesting to see how it survives and how far the original plans will be cut back, as there is already talk of reducing the numbers of trains and reducing the highest speed they will be able to run.

January 2022

For the past nine years, the majority of blog posts have been about London, north of the river, with the exception of along the south bank of the river from Lambeth to Greenwich. I have loads of photos of south London to revisit and in January I started to address the balance between north and south London with a visit to find Macs Pie and Mash shop in Peckham:

And that was the ninth year of the blog.

As well as learning so much through researching and writing the posts, it has been wonderful to learn far more from the many comments on the blog and the emails I receive provide more detail on many of the subjects covered.

For the tenth year, I will have many more posts on south London, some lengthy posts on a couple of the London Docks which I have not written about so far, posts about London’s impact on the rest of the country, and much more, along with hopefully a couple of special blog related projects.

Thanks for reading, thanks for subscribing, and perhaps I will see you on a walk later in the year.