I am still working through the locations featured in the 1973 Architects’ Journal “New Deal for East London” special issue where a range of locations, deemed to be at possible risk from future development were identified.

My first post on this subject with the full background to the 1973 article can be found here.

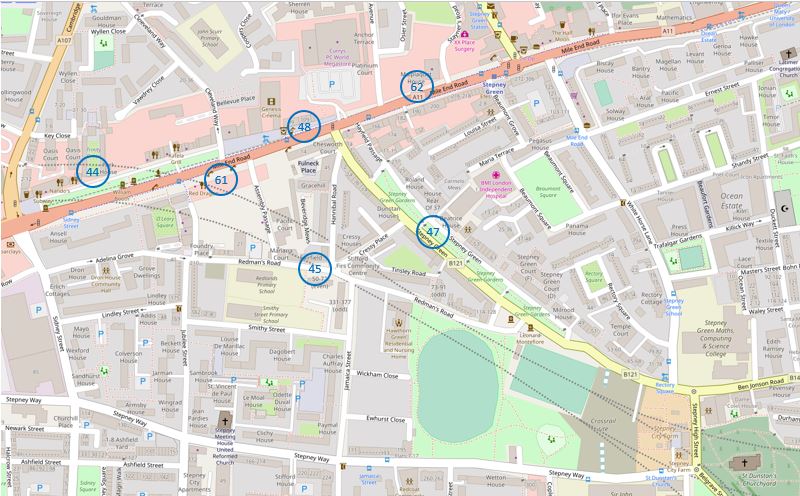

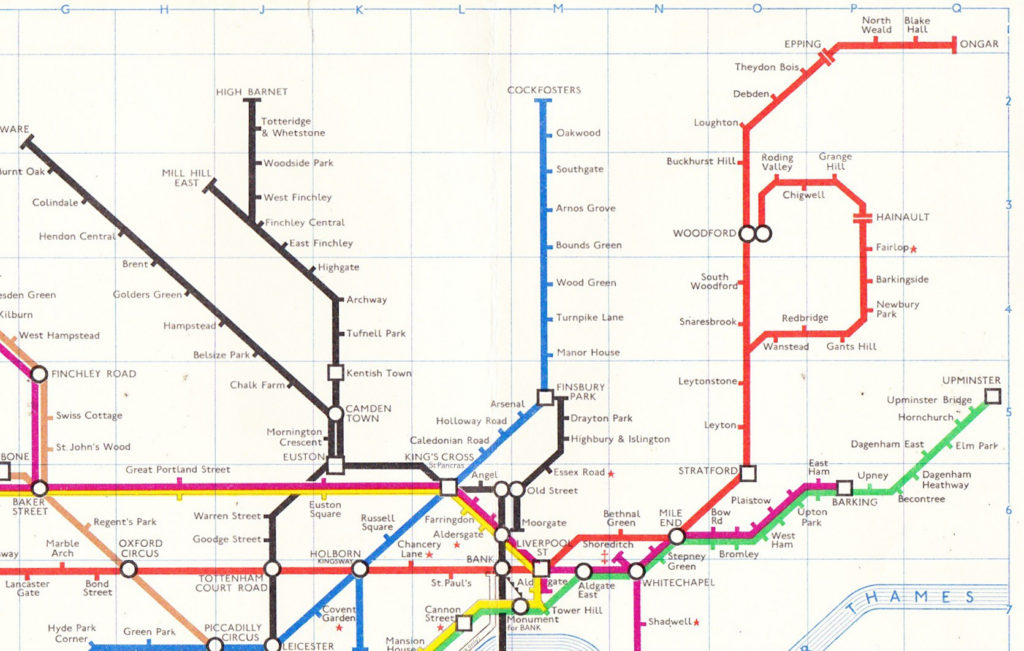

For today’s post I am in Mile End and Stepney Green, tracing the sites numbered 44 to 48, 61 and 62 as shown in the following map extract from the 1973 article (I covered site 46, the church of St. Dunstan’s a couple of weeks ago).

The Architects’ Journal identified Stepney as a Medieval Village Centre, but one that had been absorbed by the growth of east London over the past couple of centuries. I have reproduced the same locations in an up to date map, shown below, from OpenStreetMap.

There is so much history in this area that a much longer post is needed to cover fully, so my focus for today is seeing how many of the 1973 Architects’ Journal locations remain, and their current condition.

My first location was in Mile End Road:

Site 44 – 1695 Trinity Almshouses

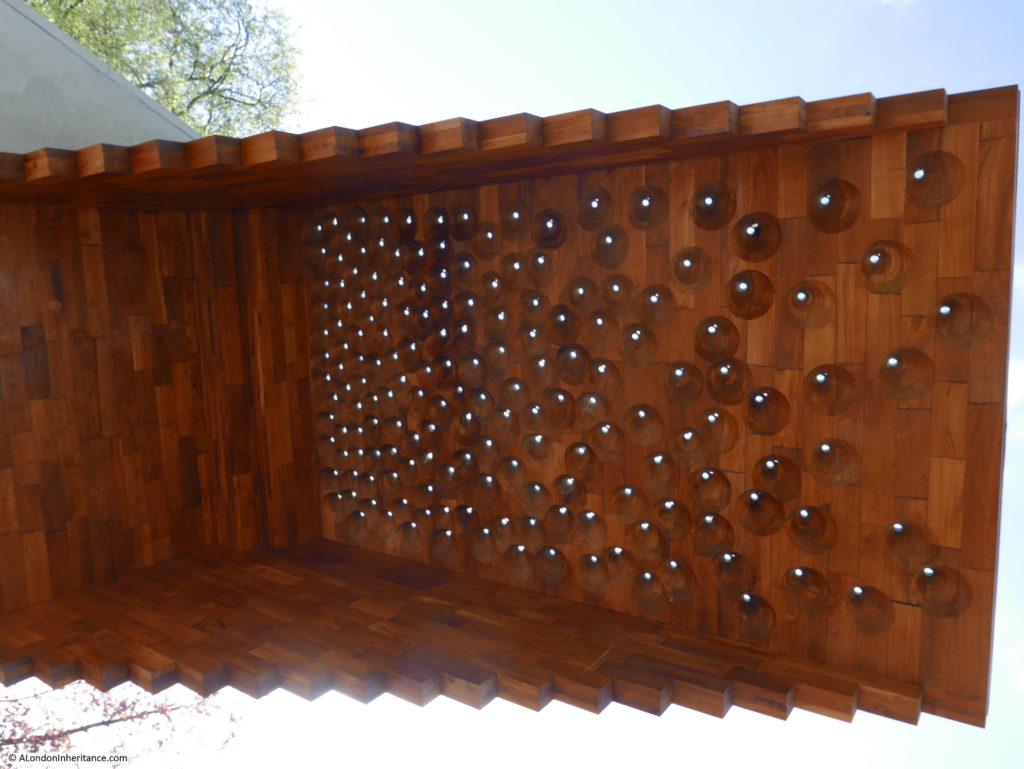

The Trinity Almshouses were built in 1695 by the Corporation of Trinity House for “28 decayed Masters and Commanders of ships or ye widows of such”. The land for the almshouses was donated by a Captain Henry Mudd and they consist of two rows of cottages either side of a green, with a chapel at the far end of the green.

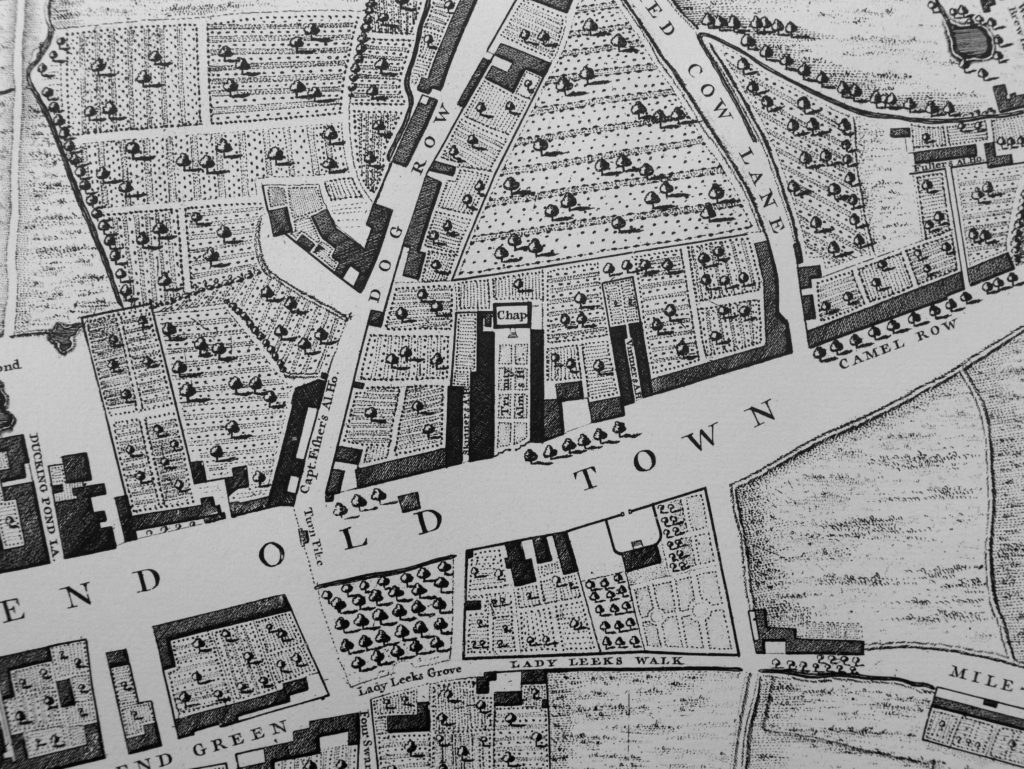

For many years after construction, the almshouses were in a very rural Mile End. The following extract from John Rocque’s map from 1746 shows the almshouses in the centre of the map, surrounded by agricultural land and fields.

The roads leading north from Mile End Road, either side of the almshouses have some interesting names. Dog Row on the left (now Cambridge Heath Road) and Red Cow Lane on the right (now Cleveland Way). Mile End Road leading through Mile End Old Town was a wide street here in 1746 as it is today.

Captain Fishers Ale House is at the end of Dog Row (I wonder how many of the decayed Masters and Commanders of ships frequented the ale house), and a Turn Pike could be found across Mile End Road opposite Dog Row.

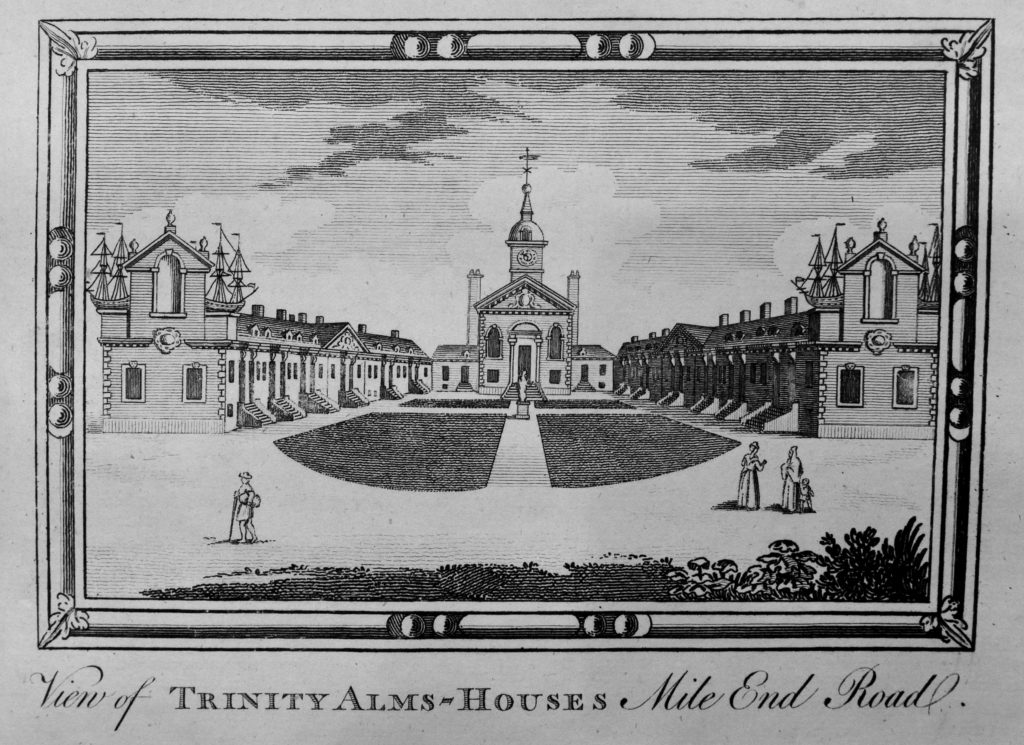

The following engraving from Chamberlain’s History of London published in 1770 shows a rather impressive view of the almshouses as they appeared at the time.

The almshouses have been under threat many times since 1695. The Corporation of Trinity House petitioned the Charity Commissioners for permission to demolish the almshouses in the 1890s, permission was refused.

They suffered bomb damage during the last war, but were repaired by the GLC, with the chapel being fitted with 18th century paneling from a house in Hammersmith.

Spitalfields Life has documented the recent threats to the almshouses

Where they reach Mile End Road, the two rows of cottages are terminated by rather ornate gable ends:

A plaque on the gable ends records the origins of the almshouses:

In the 1770 engraving, some rather impressive model ships can be seen on the gable ends. Model ships can still be seen today, however these are now fibreglass replicas with the original marble models being stored in the Museum of London.

The almshouses feature in the top right of this mural by Mychael Barratt which can be found a short distance from the almshouses:

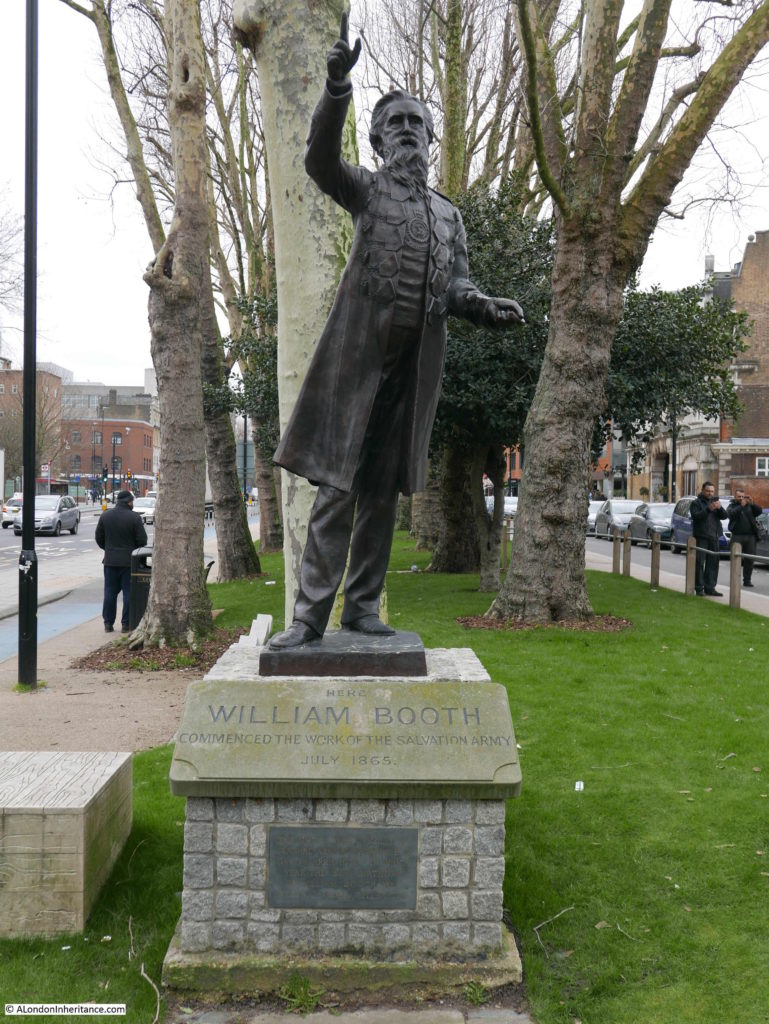

There is also a statue to William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army which was unveiled in 1979:

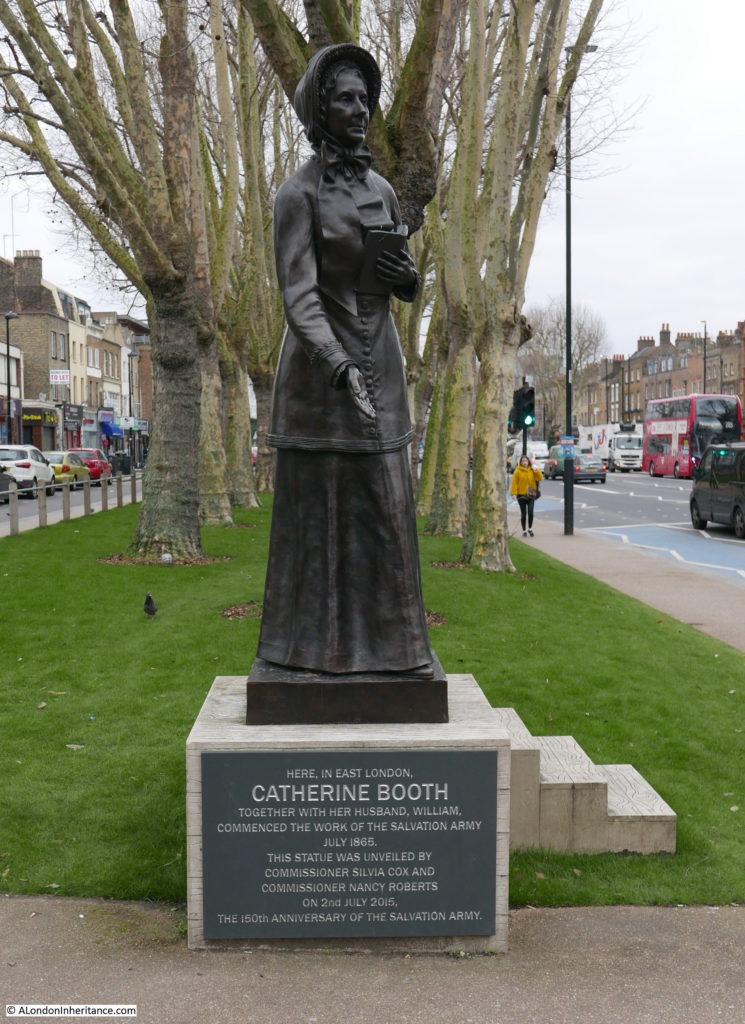

And rightly there is also now a 2015 statue to Catherine Booth to acknowledge their joint enterprise to setting up the Salvation Army:

To show just how much can be found in this short distance along Mile End Road, further along can be found this entrance to a car park and a number of businesses, however the wall on the left records an example of the type of destruction that the Architects’ Journal was so concerned about.

In 1958, fifteen years before the article was published, the site of the wall was occupied by the house that Captain James Cook occupied for a number of years in the 18th century.

The buildings either side of Cook’s house were not demolished, the apparent reason for the demolition was to widen the lane, but there was no reason then, or today, for a wider lane leading off here from Mile End Road.

It is a perfect example of the random demolition that took place in the decades after the 1940s that Cook’s house was destroyed, but the adjacent terrace of buildings was left in place, which is my next location:

Site 61 – Late 18th Century Terrace

Running to the east along Mile End Road from the location of Cook’s house is this row of late 18th century buildings:

The terrace consists of a fascinating mix of different architectural styles and modifications to the buildings. In the following example, a bay window on the first floor extends over Assembly Passage – a long, cobbled walkway that leads from Mile End Road to Redmans Road.

Across the road is the Genesis Cinema – a restored cinema (which originally opened in 1912) in a location that had been occupied by a pub, theatre and palace of varieties.

A short distance along Mile End Road from the cinema is the next Architects’ Journal location:

Site 48 – Early 18th Century Group

A lovely group of four terrace houses – it took a while to get this photo without any traffic, there is a continuous stream of traffic along Mile End Road.

Further along Mile End Road is:

Site 62 – Early 18th Century Group

A pair of large 18th century houses, set back from the road with small gardens between house and street.

To the right of the buildings is a Topps Tiles warehouse and on the left is a small open space, then the new buildings on the site of the old Anchor Brewery.

The Architects’ Journal definition for this site was a ‘Group’ rather than a ‘Pair’ so I do wonder if there were additional houses in 1973 and this pair are all that remain.

The following location was not so lucky:

Site 45 – Mutilated Early 18th Century Group

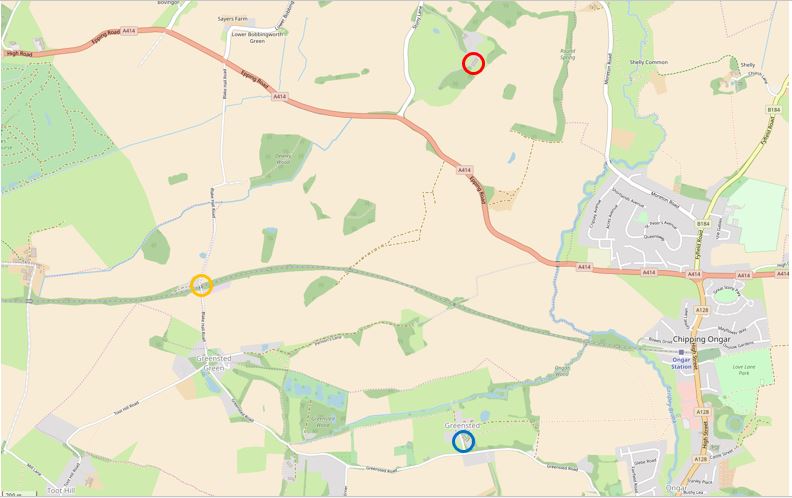

To reach my next destination I turned off Mile End Road, a short distance along Stepney Green, along Hannibal Road to Redmans Road to see if this early 18th century group remained.

If my reading of the Architects’ Journal map was right, then the terrace should have been in this location – space now occupied by the expanded playground of the Redlands School.

The houses in 1973 must have been in some state as the Architects’ Journal description was the rather strong “mutilated group”. I checked on the excellent London Metropolitan Archives Collage image archive and found this photo from 1971 of a terrace of houses along 42 to 48 Redmans Road – the space now occupied by the playground extension.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_397_71_642

The boards to the side of the doors on the central houses indicate that the houses were used in the clothing trade, with the board on the right advertising machinist vacancies.

I am sure this is the right location as to the left of the above photo, the edge of a post war terrace of flats can be seen, which are still there today as shown in my photo below.

I assume the description of mutilated indicates that the buildings have been considerably changed from their original 18th century design and structure.

I then turned back along Redmans Road to the next location:

Site 47 – Early 18th Century Remains At Stepney Green

Mile End Road is very busy, with what seems like endless traffic streaming both into and away from the City. Walk the short distance to Stepney Green and the environment changes completely. I walked through Stepney Green on a cold grey day in February and a warmer, but still grey day at the end of April, when the trees were coming into leaf and bird song was louder than the distant traffic.

The main part of Stepney Green consists of two parallel streets with central gardens running between them. The eastern street is narrow and it is along this street where the majority of the older buildings are located.

In 1746, John Rocque’s map included what would become Stepney Green as a wide area running south from Mile End Road with houses mainly on the eastern edge. Houses with large back gardens with a large open field behind. In 1746 the area was called Mile End Old Town rather than Stepney Green.

This is the view down the eastern side of the central green.

The layout from 1746 can still be seen today as the 1746 map indicates a narrow street in front of the houses to the east, trees along the centre with a wider road on the western side – the same layout can be seen today.

The central gardens are tree-lined on either side with a pathway winding through the middle.

The Architects’ Journal map shows houses on either side at the northern end of Stepney Green with additional houses marked on the eastern side. This distinctive terrace of four houses is along the northwest corner.

The houses along the eastern edge tend to be larger, more individual buildings.

One of the most important buildings in Stepney Green is number 37 – a magnificent Queen Anne house that was built in 1694. The house was purchased by the Spitalfields Trust in 1998 who restored the house from institutional use to a rather magnificent family dwelling.

Number 37 Stepney Green:

A closed pub on the western side of Stepney Green that has been converted to a private residence. Originally the Ship, then for a few years before closure, the Ship on the Green:

The LMA Collage archive has a photo of the Ship as it was in 1953:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_399_F8790

The view across Stepney Green.

In the above photo, the house to the left of middle has an interesting plaque above the door. The house must have been occupied by a dispensary at some point as the plaque records that the equipment for the dispensary was provided by a fund raised by the Mayor of Stepney in memory of King Edward VII, for the prevention of consumption.

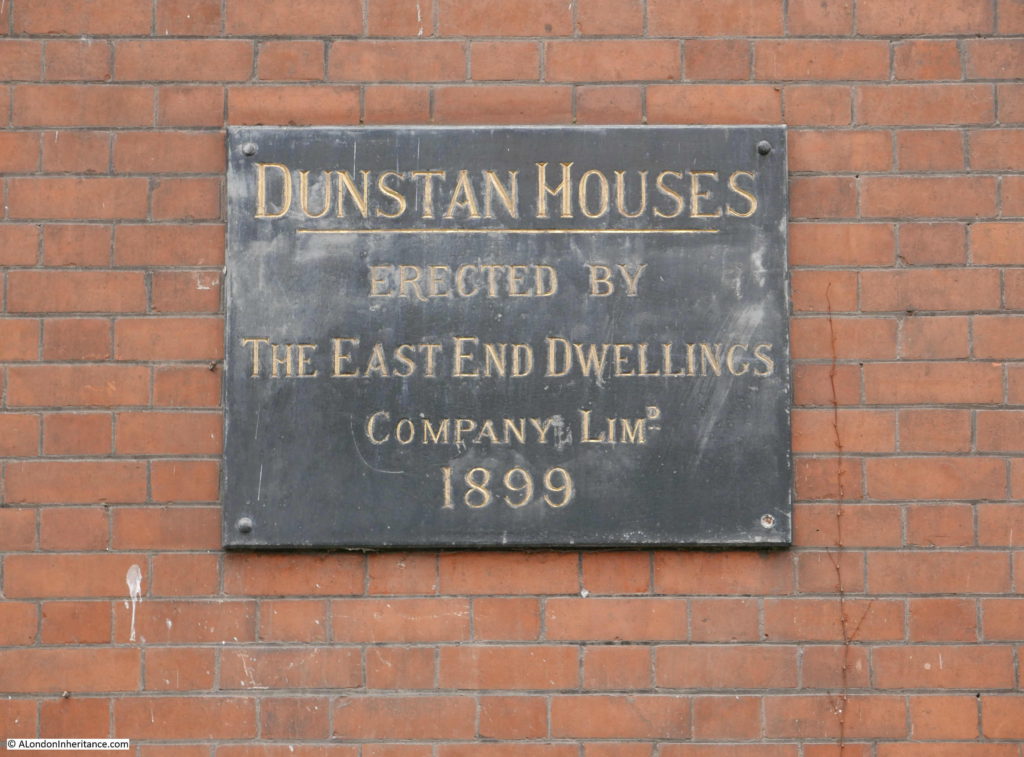

The corner of Stepney Green and Cressy Place is occupied by Dunstan Houses, built by the East End Dwellings Company Ltd in 1899:

The East End Dwellings Company was formed in the early 1880s by the vicar of St. Jude’s, Whitechapel, the Reverend Samuel Augustus Barnett. The intention of the Company was to provide housing for the poor, including those who other philanthropic housing companies often avoided, such as casual, day labourers.

Another of the large housing developments by late Victorian philanthropic companies can be found towards the southern end of Stepney Green.

Stepney Green Court was built by the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company. The name of the company came from the plan that a four per cent return could be made on the investment needed to construct good housing which could be provided at an affordable rent.

Stepney Green Court was built in 1895.

The building features some very ornate decoration:

Towards the end of Stepney Green, where the central gardens and eastern side road have ended, is the remains of an interesting building.

On a small corner of the main Stepney Crossrail construction site are these brick walls and ornate entrance:

These are the remains of a Baptist Chapel. The Crossrail Architectural and Historical Appraisal identifies the walls and door as the remains of a Baptist Chapel, possibly built around 1811.

The LMA Collage archive has a photo of the area showing that the remains of the Baptist Chapel were in a poor state in 1969.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_399_69_3379

All the buildings on the left have been demolished and the whole area is now a Crossrail construction site.

Entrance to the construction site:

With the exception of the “mutilated early 18th century group” in Redmans Road the buildings listed in 1973 have survived well. The houses along Mile End Road face onto a very busy road into the City, however turn off Mile End Road into Stepney Green and you can find one of those historic landscapes that London conceals so well.

It will be interesting to see what happens to the remains of the Baptist Chapel and the construction site, once work is completed – hopefully something that blends in with the area rather than bland apartment buildings that can be found anywhere across the city.

A the end of Stepney Green is the large churchyard and church of St. Dunstan and All Saints.