The Festival of Britain and the Atomic Bomb – two very different subjects, but with a connection, and which also both show different expectations of the future in the early 1950s. The Festival of Britain put forward a vision of hope for the future, a country with strong industrial and cultural traditions, based on the history of the British people and the land they inhabited. The atomic bomb put forward a terrifying vision of destruction as the world descended into the Cold War.

I hope all will become clear by the end of the post.

Festival Ship Campania

I have written a number of posts about the Festival of Britain (there is a list of links at the end of the post). The festival presented a view of the country based on the people and the land. History, industry, science and creativity all featured, as well as what the organisors portrayed as Britain’s contribution to civilisation and the rest of the world.

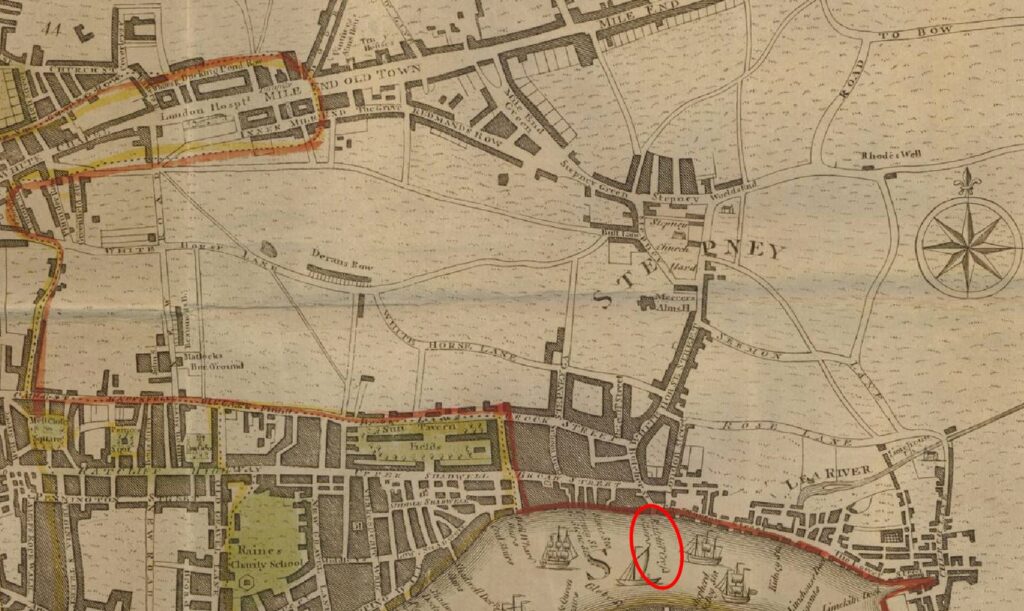

The main Festival of Britain exhibition site was in London, on the South Bank, and this, along with the Pleasure Gardens at Battersea are probably the most well known festival locations, however the intention with the festival was to get as many people across the country involved as possible. There were fixed exhibitions in Glasgow and Belfast, a travelling land exhibition, and also an exhibition within a ship that sailed around the coast of the country, and brought the festival to several major port cities.

The exhibition was in the Festival Ship Campania:

The Campania had been a “ferry carrier” during the war. The role of a ferry carrier was to transport aircraft between locations. Whilst aircraft could land and take off from the ferry carrier, this was more for delivery of aircraft than for combat, although planes from the ship were involved in a number of combat operations.

The Campania had been used on artic convoys, delivering aircraft to Russia to support the eastern front and the Russian campaign against the Nazi’s..

As with all other Festival of Britain exhibitions, there was an official guide book published for the Festival Ship Campania, and the following from the guide book provides more detail about the ship:

“This is the first time that an exhibition of this size has been presented in a ship. Clearly the primary requirement in an Exhibition Ship is adequate display space, and for this reason Campania was chosen; for she has a hanger deck 300 feet long, and high enough for galleries to be built to increase the Exhibition area.

H.M.S. Campania was laid down as a merchant vessel at the yard of Messrs. Harland & Wolff. She was taken over during the last war by the Admiralty while still on the stocks, and converted into a ferry carrier. In this role she had a distinguished career. She has been lent by the Admiralty as a Naval contribution to the Festival of Britain. Her conversion to a Festival Ship has been planned by the Director of Naval Construction, Sir Charles Lillicrap, in conjunction with Mr. James Holland, the Exhibitions Chief Designer. It was carried our by Messrs. Cammell Laird of Birkenhead.

During her time as a Festival Ship, Campania is flying the Red Ensign. She is manned by a Merchant Navy crew and managed on behalf of the Festival of Britain by Messrs. Furness, Withy & Co.

F.S. Campania is a motor ship with two diesel engines, 13,000 h.p. and has a speed of 18 knots. Her principal dimensions are: overall length 540 feet, beam 70 feet, draught 23 feet, gross tonnage 16,408.”

The guide book for the Festival Ship Campania has the same design features of all the festival guides, with the front covering featuring the symbol of the festival, designed by Abram Games. As with all other guides, the book is “A Guide To The Story It Tells”, and was written by Ian Cox, the Festival’s Director of Science and Technology, who was from the Ministry of Information:

The displays on the Campania were a mini version of the South Bank site, with main exhibition themes of The Land of Britain, Discovery and The People at Home.

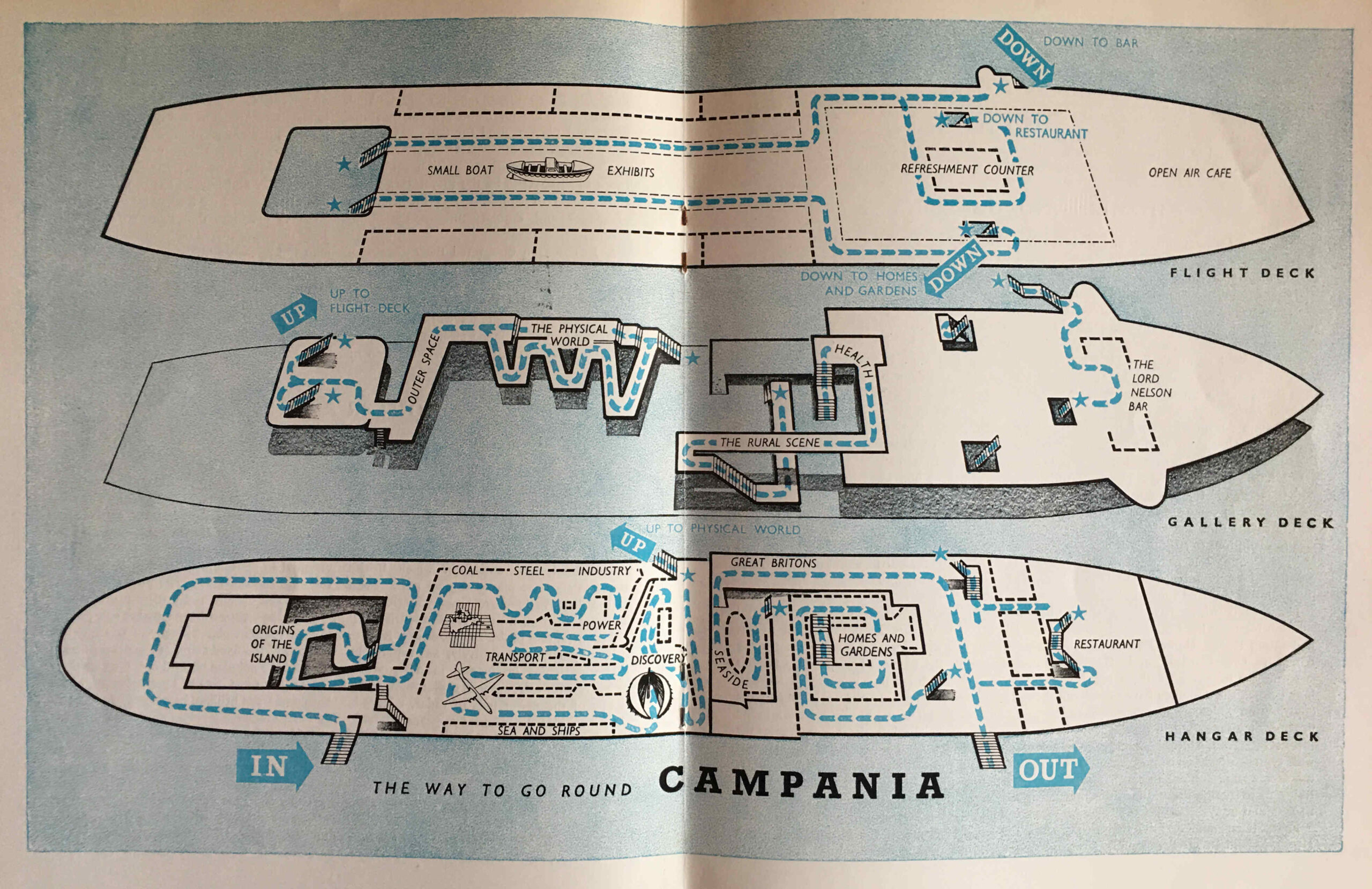

The exhibits and displays were spread over three decks of the ship, and the benefit of the Campania was that it had a large hanger deck and flight deck which were used for displays.

The guide book included a diagram of the ship showing the three decks, the subjects of each display area, and a recommended way around the exhibition:

As with the other exhibition locations, the Campania was fitted out with a restaurant, bar and café to enhance the overall visitor experience.

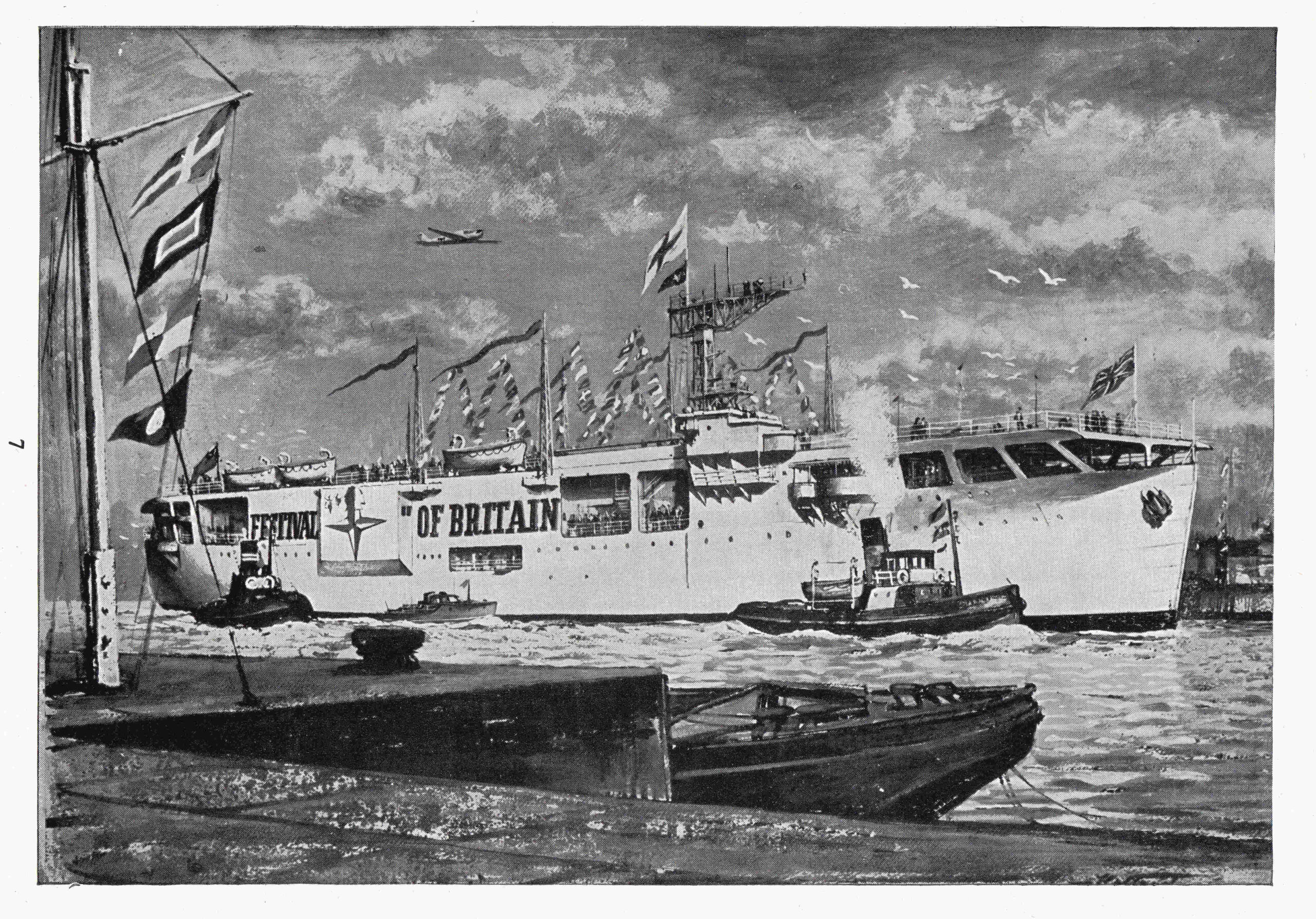

The side of the ship was decorated with the Abram Games festival sumbol and the words Festival of Britain. Coloured flags decorated the flight deck, as shown in this illustration from the guide book:

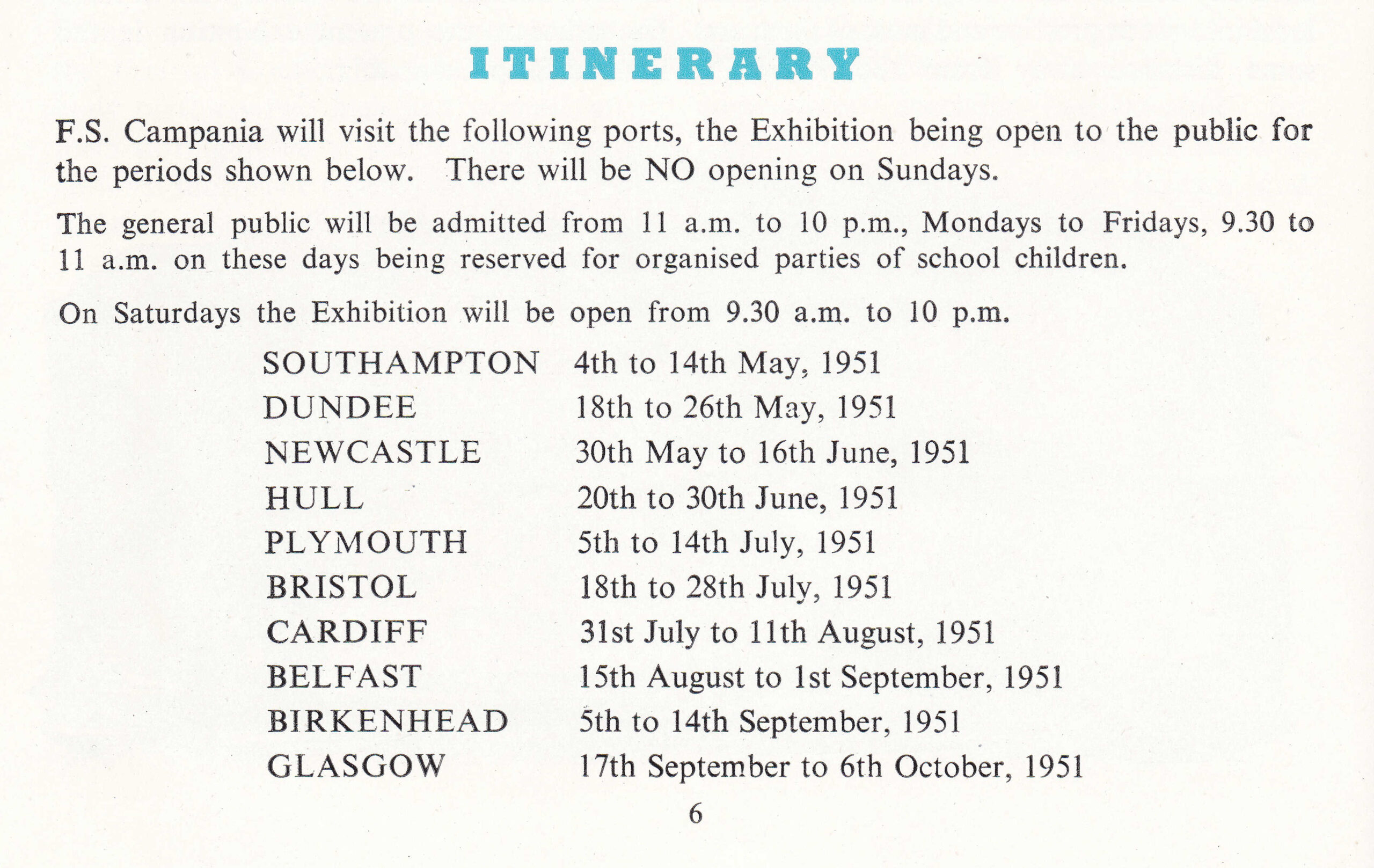

The Campania toured the coast of the country for the same period of time as the main festival on the South Bank, starting at Southampton in early May and ending at Glasgow in the first week of October, soon after the South Bank site closed. The following table from the guide shows the ports of call, and the duration of each visit:

There were very many school trips to the ship, some of which included the organisation of special trains, as for example, from the New Milton Advertiser on the 19th of May 1951:

“Between 600 and 700 Brockenhurst County High School pupils went to Southampton by special train on Friday in last week to visit the Festival Ship Campania. A section of the party also cruised round Southampton Docks in a specially chartered vessel.”

The Liverpool Echo reported on the visit of the ship to the city, and included some highlights of what could be seen onboard, including models of an “Underground railway junction and London Airport as it will be when completed, a jet engine and a seaside pub, several full-size boats and working models of busy shipping ports”.

The article ended by stating that “This is Birkenhead’s Great Festival Show – the one you mustn’t miss”.

During the visit of the Campania to Belfast, the officers and many of the organisors and administrative staff on the ship were treated to a reception by the Northern Ireland Government, and the Belfast Newsletter reported that on the day of the reception there had been a total of 4,909 visitors to the Campania.

The popularity of the exhibition on the Campania seems to have had an impact on the experience for those on board. A visit to the ship by children of the Holy Trinity Secondary Modern School in Bradford-on-Avon, was reported in the Wiltshire Times as “The visit was somewhat marred by the terribly overcrowded conditions on the ship”.

The visit of the Campania seems to have been a great success at all the ports of call, with newspapers reporting high numbers of visitors to the exhibition, although I suspect that as well as the Festival of Britain exhibition, the opportunity to look around a large ship that had seen service in the war just six years before, must have been a major incentive.

As with all the Festival of Britain Guide Books, the book for the Festival Ship Campania had a number of adverts, many colour, and for the Campania, many of these adverts had a maritime theme, such as the advert of the Marconi company:

One of the key themes for the festival was Britain’s industrial and scientific strengths, and how these would contribute to the future of the country.

I doubt anyone in 1951 could foresee the industrial decline of the country over the next 50 years when almost every company featured in the adverts across all the festival guides would disappear, with the majority being taken over by foreign competitors.

The Marconi company featured in the above advert went through several changes of ownership, and became part of GEC, which sold some of the business to BAE. GEC renamed itself as Marconi during the so-called dot com bubble, buying a number of US networking companies at very high prices.

Losses became significant, parts of the firm were sold, shares were suspended and Marconi as a business folded in 2006. A small part of the once sprawling empire remains as Telent.

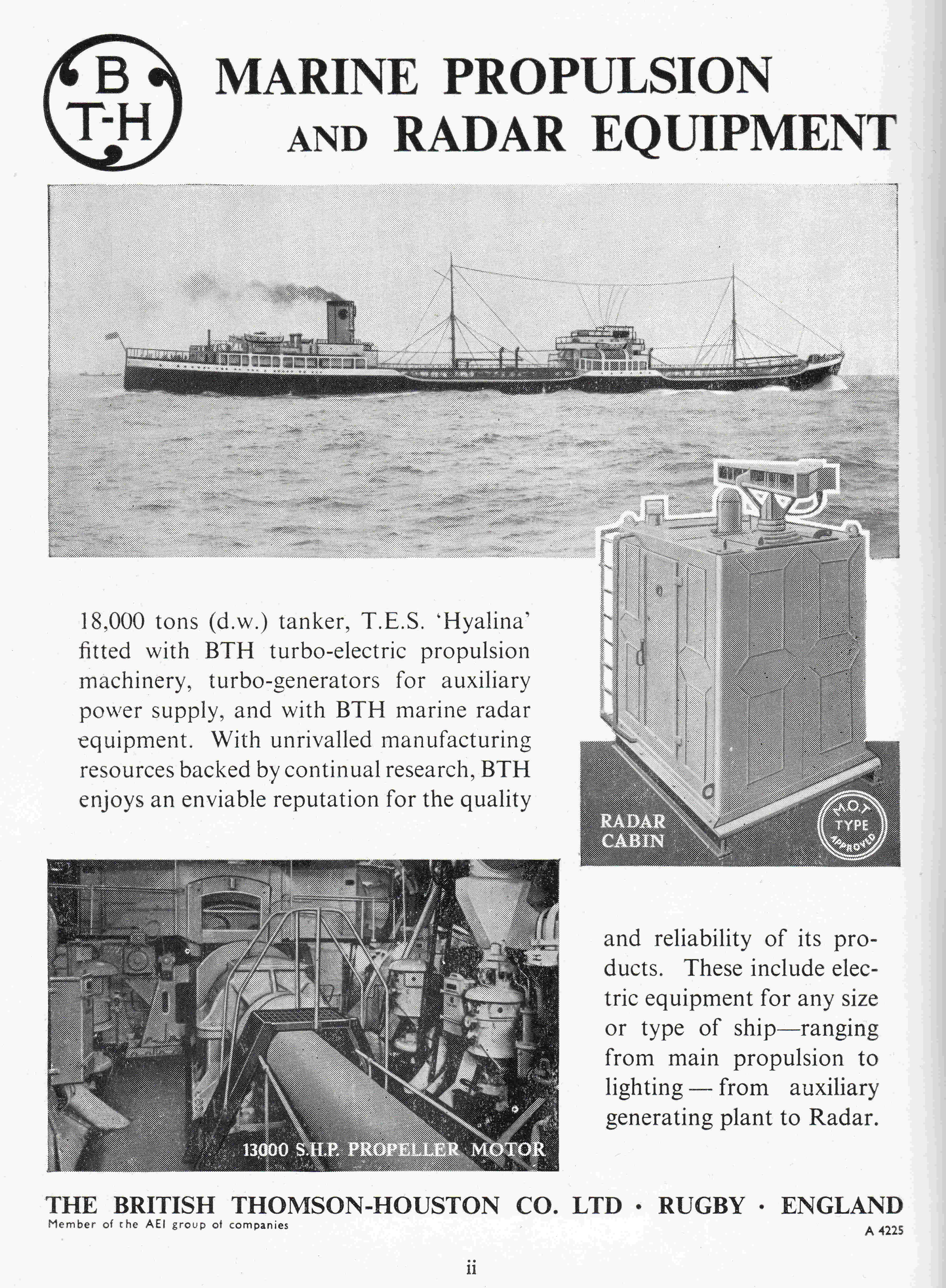

British Thomson-Houston was part of the gradual consolidation of British industry, eventually being owned by GEC:

The South American Saint Line was a Cardiff base shipping company that operated cargo routes between Dover and European ports, and Cardiff and South American ports, for example taking coal to Argentina and returning with a cargo of grain. The business was closed in the early 1960s, with routes and ships being sold to other shipping companies.

Even if a company had no maritime connections, they tried to include an appropriate reference in their advert:

British Aluminum was taken over by US and Canadian companies, and all UK based operations seem to have closed in the early 2000’s:

The discovery referenced in the following advert for the British Oxygen Company was made by two French brothers, Arthur and Leon Brin who founded Brin’s Oxygen Company, soon after renamed as the British Oxygen Company, which was taken over by the German company Linde in 2006:

And finally, I doubt that the companies behind the Shipbuilding Conference who issued the following advert, could have expected the British ship building industry to be at such as reduced state some 70 years later:

The Festival of Britain tried to mix industrial strength, leading edge science and design, with a rather romantic view of the country’s culture, history and relationship between the people and the land.

One of the Theme Conveners for the exhibitions on the Campania was Jacquetta Hawkes, a British archeologist and writer. who in the same year as the festival, published probably her best known book “A Land”. A really difficult book to classify, it has been described as a deep time dream of the country’s archaeology. There is a good review of the book here. It is a fascinating read, and although we cannot visit the Festival of Britain today, it is a sort of published form of the “Land” parts of the festival.

Back to the Campania, and during the Second World War, the ship was used to ferry aircraft and many other supplies and equipment to Russia, who were fighting the German’s in the east. Aircraft on the ship were also used to defend the convoys, with a U-Boat being sunk in 1944.

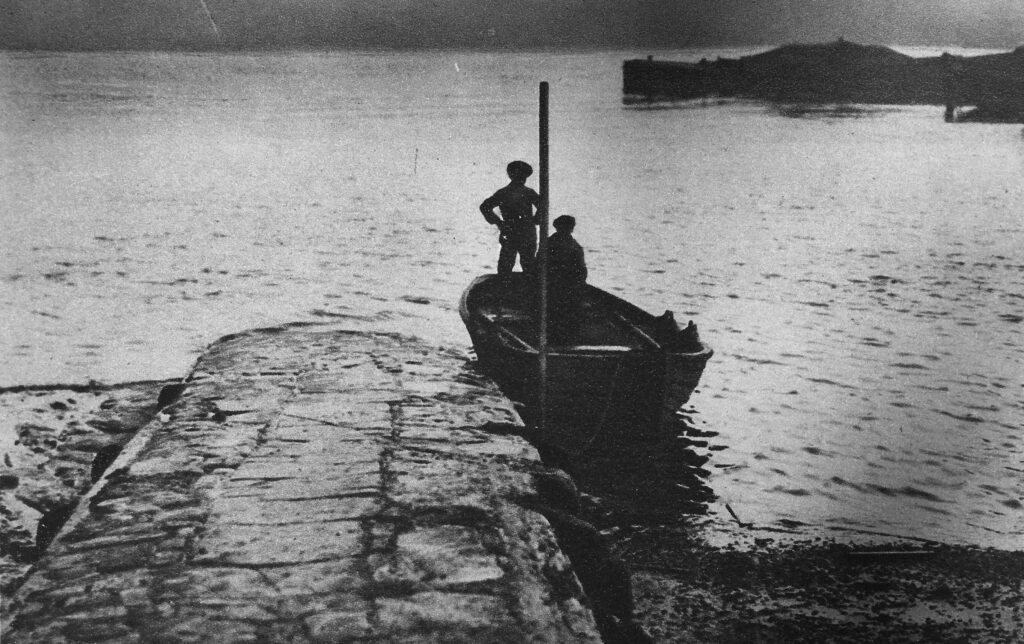

View of the Campania at sea:

The route taken by these convoys was around the northern edge of Norway and Finland to reach Arkhangelsk in Russia. Conditions were appalling. There was the constant threat of attack from German aircraft, ships and submarines as well as dreadful weather conditions, as shown in the following two photos of the Campania during a convoy:

When decks would be covered in thick snow and ice – very different to the open air café on the deck during the festival:

After the end of the Second World War, the Campania was decommissioned. Many ships which had served a temporary purpose during the war were sold or scrapped, however the Campania was put on the reserve list, and was therefore available for the Festival of Britain.

After the festival, the ship returned to the navy, which brings us to the second part of the title of the post:

Operation Hurricane and the Atomic Bomb

During the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project underway, as did the Americans. The cost, complexity and need for a rapid solution in the development of such a weapon resulted in the US, UK and Canada working together on what became known as the Manhattan Project, with the partnership being formalised by the Quebec agreement of 1943.

Under this agreement, British scientists worked with the Americans in the development of the atomic bomb, and shared the UK’s work up to that point.

After the war, the US ceased all cooperation with the British, and did not share any of the development work that led to the bomb produced by the Manhattan Project.

This was mainly down to the perceived risk of sharing such knowledge, and that the Quebec agreement gave the British a veto in the use of atomic weapons.

In 1949 the Russians tested their first atomic bomb, and in 1950 the German physicist Klaus Fuchs, who had fled from the Nazi’s, and was part of Britain’s early research into the atomic bomb, and then the Manhattan project, was found to have shared secrets with the Russians.

He was sentenced in a British court and imprisoned, however the US viewed this as a further risk of working with the British and ended any remaining cooperation, including the use of US test sites.

So the US and Russia had the atomic bomb, and in the late 1940s, the UK still believed that it had a “Great Power” status, and having atomic weapons was essential in maintaining that status.

In 1947, the Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, approved the creation of the High Explosive Research Project, which would be responsible for the development of a British designed and built atomic bomb.

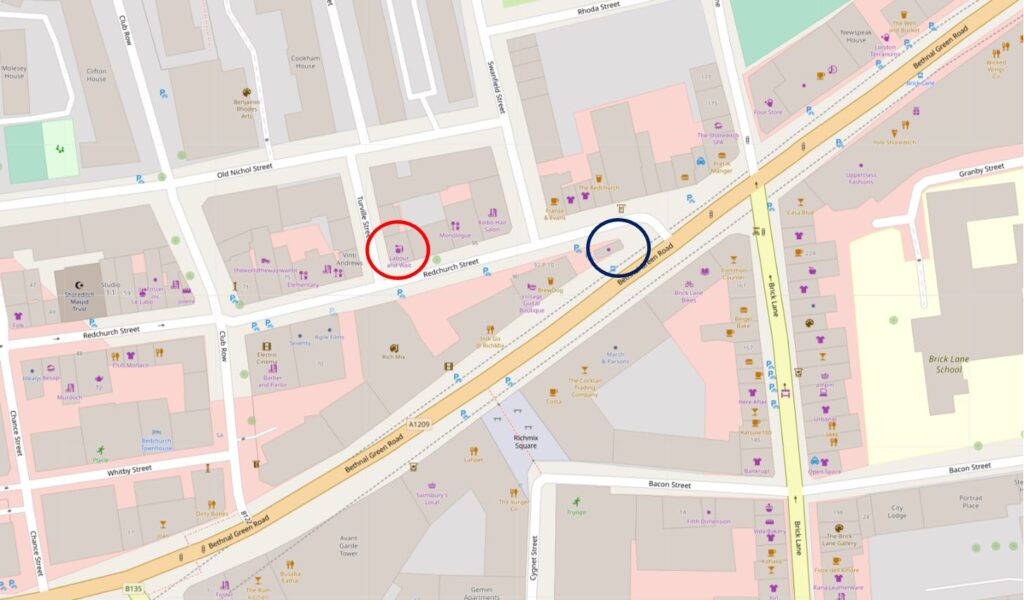

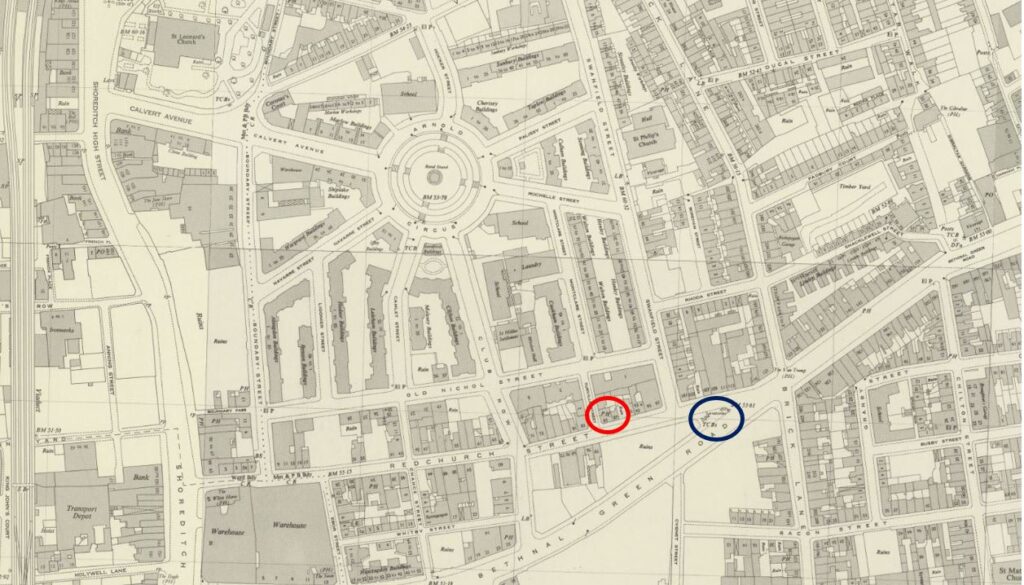

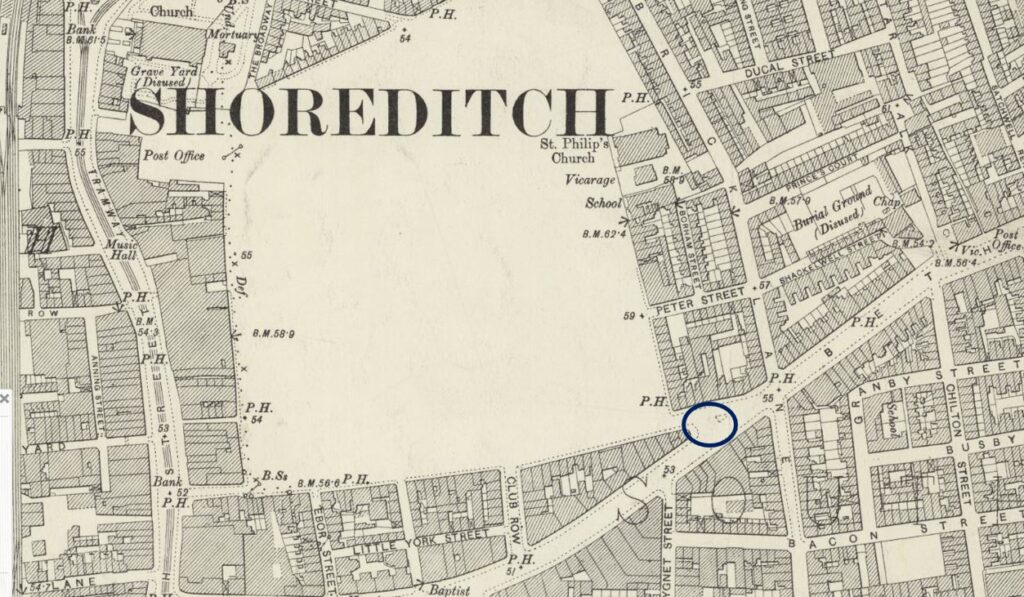

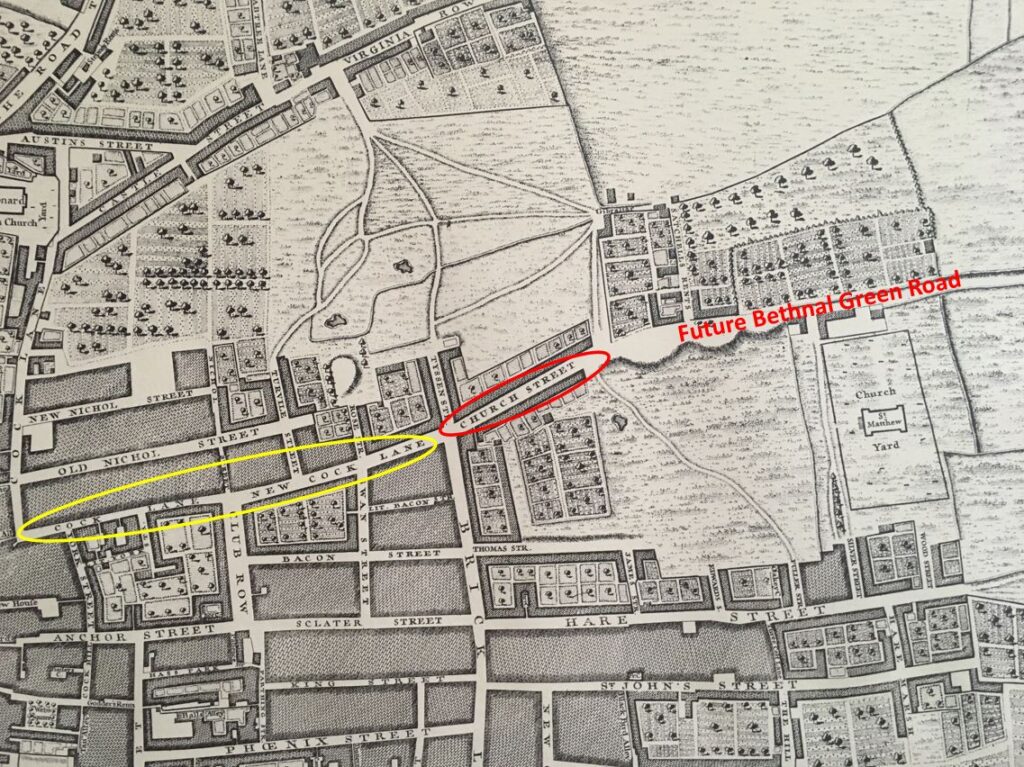

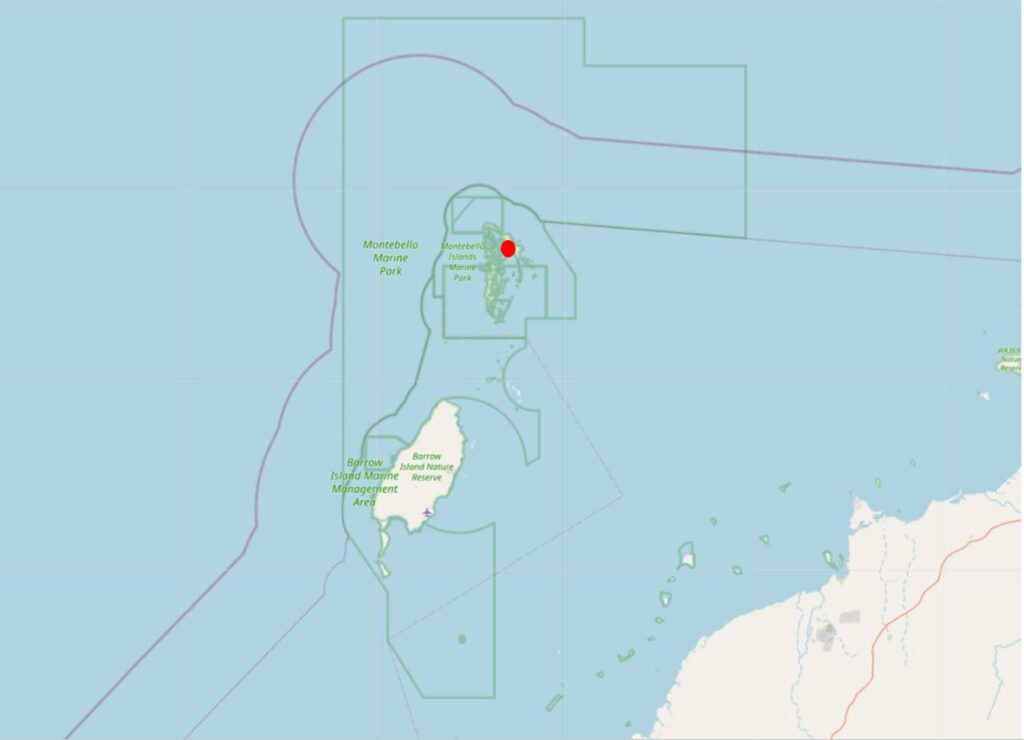

As well as developing the bomb, a site was needed to test. The US had refused access to their testing grounds, so a search was underway for a suitable site, which finally settled on the remote Montebello Islands off the west cost of Australia. The location of the islands is shown by the red circle in the following map ( © OpenStreetMap contributors):

Operation Hurricane was the name given to the first test of Britain’s atomic bomb, and when it had been built, a fleet was assembled with Campania given the role of Flag Ship, sailing from Portsmouth where the ship had been equipped for the role, to the western Australian test site..

The 25 kiloton bomb was to be exploded on board a redundant British frigate called HMS Plym. It was placed in the hold, below the water line as one of the intentions was not just to test the performance of the bomb, but also the impact of an atomic bomb being smuggled onboard a ship into a British harbour.

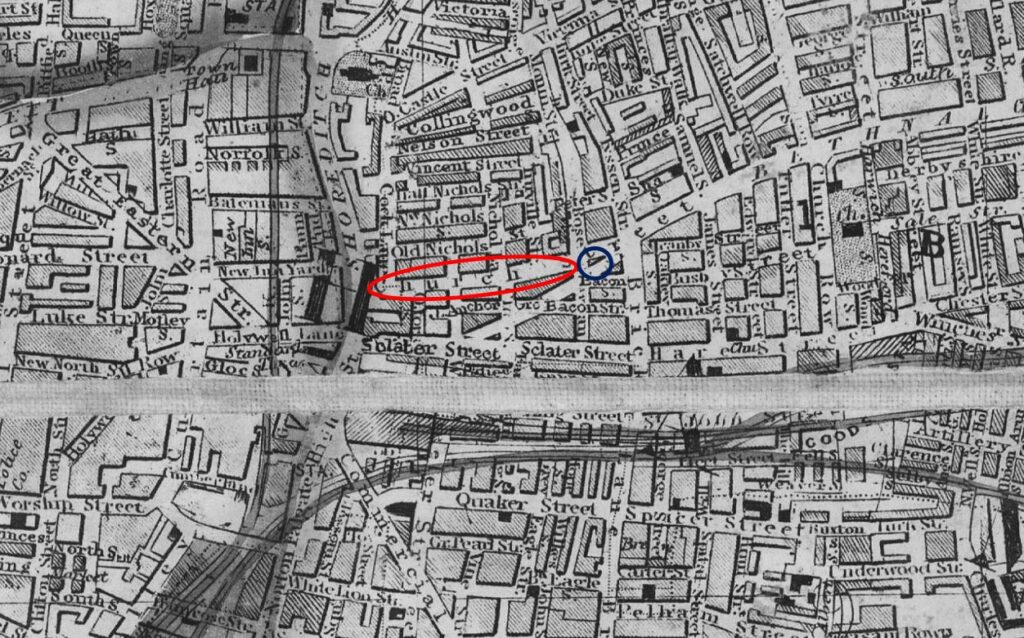

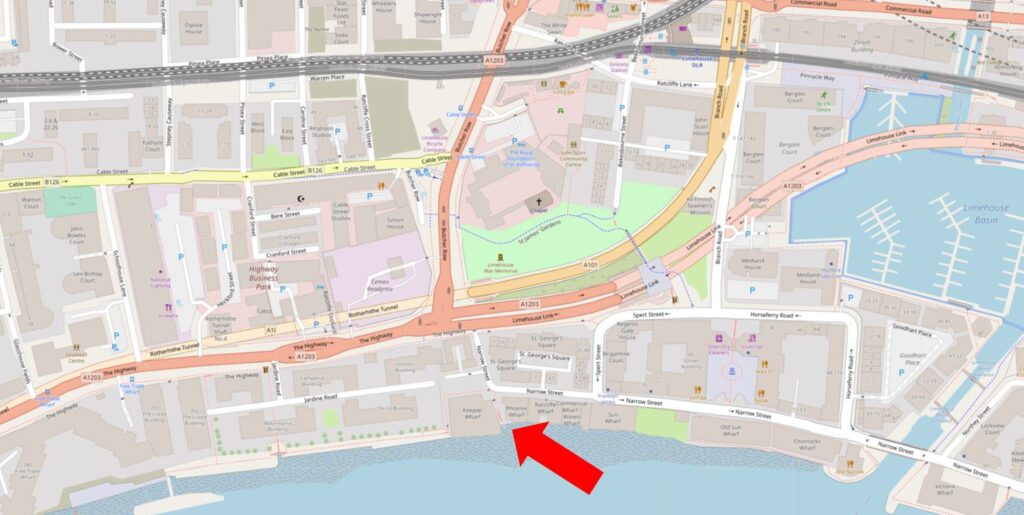

The location of the Plym, and the bomb’s detonation within the Montebello Islands group is shown by the red dot in the following map ( © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The bomb was exploded just before eight in the morning (local time), on the 3rd of October, 1952. Exactly a year before, the Campania was moored at Glasgow in the last few days of its role as the Festival Ship.

There is far too much on the story of Operation Hurricane than I can include in a weekly post. For lots more detail, the Ministry of Supply produced a film showing the full story from the development of the bomb, through to the test and explosion. This film is on the Imperial Museum website, and is in three parts.

The first part covers the development of the bomb, and also includes the departure of the Campania from Portsmouth. The second part covers preparations, and the third and final part covers the final preparation of the bomb, the explosion and the testing carried out after the explosion.

All three parts to the film can be found at this link.

The film shows not just the devastating impact of an atomic bomb, but also the very rudimentary safety precautions – if you could call them that – for those who participated in the test.

HMS Plym, the ship on which the bomb had exploded had been vapourised, with only a few small fragments of radioactive metal to be found. A large crater was left on the seabed below where the ship had been located.

A wide range of samples were taken from sea water and the land of the islands. Structures had been built on the islands to see how these would have withstood the blast from an atomic bomb, and the impact on these was measured and photographed.

Churchill, who by the time of the test had been re-elected, declared in the House of Commons that the test had been a success and lived up to expectations.

Those who had been involved in the test and witnessed the explosion were sworn to secrecy, as this newspaper report from the 16th of December 1952, when the Campania returned back to Portsmouth explains:

“Atom sailors home with censored story – Five hundred and seventy officers and men of Britain’s atom ship, H.M.S. Campania, back in Portsmouth yesterday from the Pacific, have been put on their honour. And it means that for once Jack Tar cannot talk about his sea travels.

For he knows what happened when Britain’s atom bomb exploded off the Monte Bello Islands; he knows what effect it had on vegetation and test shelters, and some of his colleagues from the vaporised ship, H.M.S. Plym, know what it looks like. He must not say a word.

Before the first of the Campania’s crew went ashore last night they were reminded: ‘Tell them your impressions of the explosion and nothing more. keep to what Dr. Penney said on the B.B.C. and Mr. Churchill in the House. Your are on your honour’.

To make sure these security instructions were fully understood the ship’s company were lectured on board by Rear Admiral A.D. Torlesse, in charge of Operation Hurricane, officials of the Supply Ministry and Dr. William Penny.

Copies of the Admiral’s Speech and Mr. Churchill’s statement in Parliament, were posted on the ship’s notice boards and each man was given a copy.”

In the final part of the Ministry of Supply film on the IWM website, there are some scenes showing a helicopter taking samples of water, and dropping them into a box on the ship.

This was also reported in the press with the rather dramatic headline of “They Got Half Pint Of Death Water“:

“The two men with the most dangerous job of the atom test – they flew a helicopter over the danger spot to get a sample of deadly radioactive water – were Lt. Comdr. Denis Stanley of Thruxton, Hampshire, and Commissioned Observer H.J. Lambert of Carnoustie.

To them it was ‘just another flight’ but that routine flight meant going to within 30 feet of radio-active water only two hours after the explosion.

While Stanley piloted the plane, Lambert was checking the Geiger counter and other instruments. He was watching for a danger point when the flickering dials would indicate that they would have to turn back.

Beneath the aircraft was a canister, like a half-pint milk bottle, said Lambert, suspended 20 feet below by a piece of string. We flew slowly, said Stanley, so as not to spill any of the water. The canister was supposed to be unspillable, but we took no chances.

Said Lambert: We had practised for six weeks lowering a small canister into a box. What happened to the water? we never saw it again. The boffins took it, I suppose.”

After the success of the test, the bomb was developed into the Blue Danube bomb that was Britain’s first operational atomic weapon and for which the V-bomber aircraft were designed and built.

The bomb tested in 1951 had a yield slightly higher than the bombs dropped on Japan at the end of the Second World War.

Not long after the British tests, the US tested a Hydrogen bomb, which had a yield of some hundreds of time greater than the British design, so in many ways, the British bomb was redundant soon after the test.

The wider impact on those who participated in Operation Hurricane are outside the scope of today’s post, however there is a really good summary in a Daily Mirror investigation, which you can find here.

The Montebello Islands are now part of a Marine Conservation Reserve, and radiation levels have reduced to a point where the islands are now open to visitors.

So that is the connection between the Festival of Britain, and the test of Britain’s first atomic bomb. The Festival Ship Campania, carried an exhibition around the ports of the country, showing the history of the country, British contribution to science and technology, British industry, design and culture.

A year later, the same ship was a witness to the atomic bomb, a threat that would come to define much of the final half of the 20th century during the Cold War, and which rather frighteningly seems to have returned with current world politics and wars.

HMS Campania was decommissioned in December 1952 after returning from Australia. Three years later in 1955 the ship was sold and scrapped.

You may also wish to read:

And my posts on the Festival of Britain:

- The Festival Of Britain South Bank Exhibition

- A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Upstream Circuit

- A Walk Round The Festival Of Britain – The Downstream Circuit

- The Festival Of Britain – Maps, Football, Guidebooks. Science And Abram Games

- The Festival Of Britain Pleasure Gardens – Battersea Park

- The Lansbury Exhibition Of Architecture

- The Exhibition Of Architecture – The Final Chapter