For this week’s post, I am in Charing Cross Road to track down a couple of photos I took in 1979, and a later “shop front” photo from 1986.

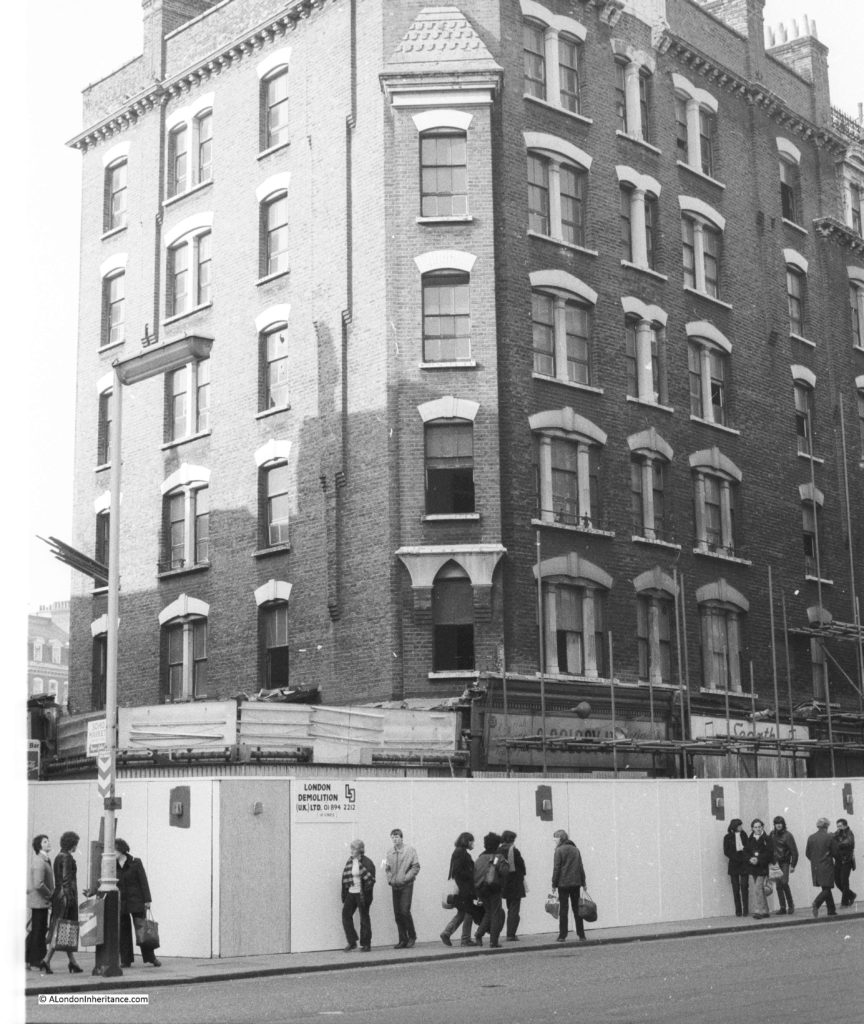

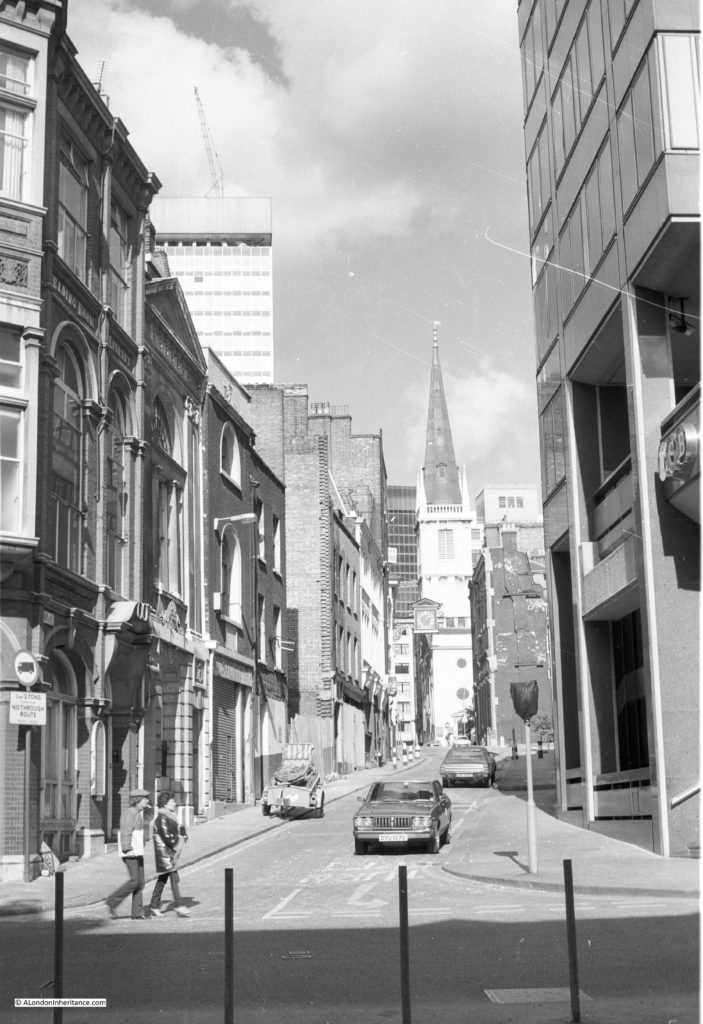

This was the view in 1979, looking north along Charing Cross Road, close to the junction with Great Newport Street.

The same view in 2019:

In 1979, there were two, almost identical buildings on either side of the street. Both of these were named Sandringham Buildings and were constructed when this length of Charing Cross Road was created. The building on the left in 1979 was replaced by the block we see today, running roughly the same length of the street and with a similar approach of shops on the ground floor and flats on the upper floors.

I took these photos specifically because of the impending demolition of the building – something I have always try to do when I see a building at risk. The following photo shows the corner of the block. The signs of the shops that once occupied the ground floor can just be seen behind the scaffolding.

The other location I wanted to track down was this 1986 photo of a tobacconist at number 74 Charing Cross Road, one from a series of shop front photos in the area.

The same location in 2019 – no longer a tobacconist.

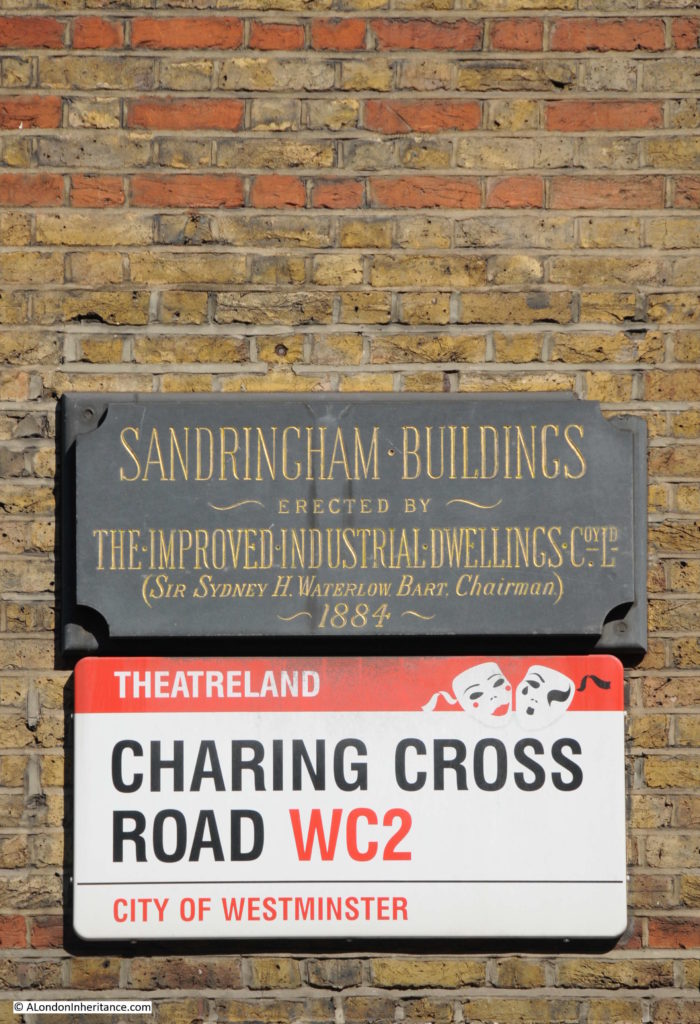

The shop is one of those along the ground floor of the remaining block of Sandringham Buildings, along the eastern side of Charing Cross Road. The history of Sandringham Buildings is integral to the reconstruction of the area that resulted from the development of Charing Cross Road.

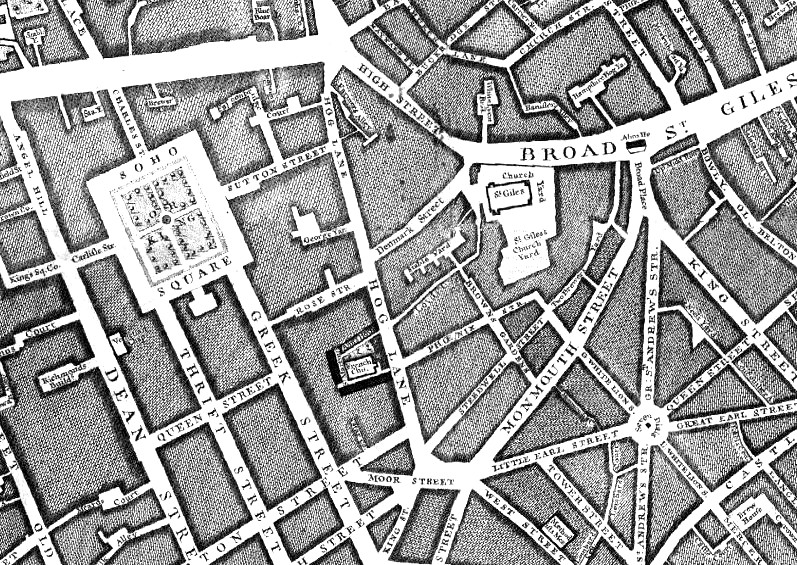

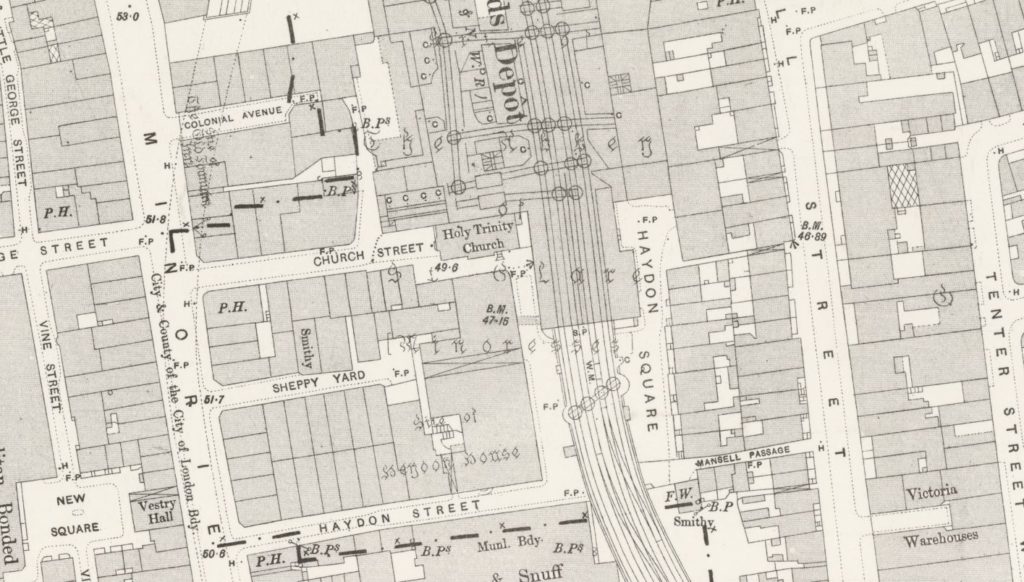

To understand how Charing Cross Road has developed, we can start with John Rocque’s map of London from 1746. Charing Cross Road does not yet exist as a through route from the junction of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, down to the future location of Trafalgar Square. Part of the road that would become Charing Cross Road can be seen in the centre of the map, but named Hog Lane.

The name probably came from the location of a Pound at St. Giles (roughly around the junction today of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road), where animals were held as they were driven into London, as a stop before the final push into the City markets (I wrote more about Saint Giles Pound at this link).

Hog Lane ended just north of where Cambridge Circus is today.

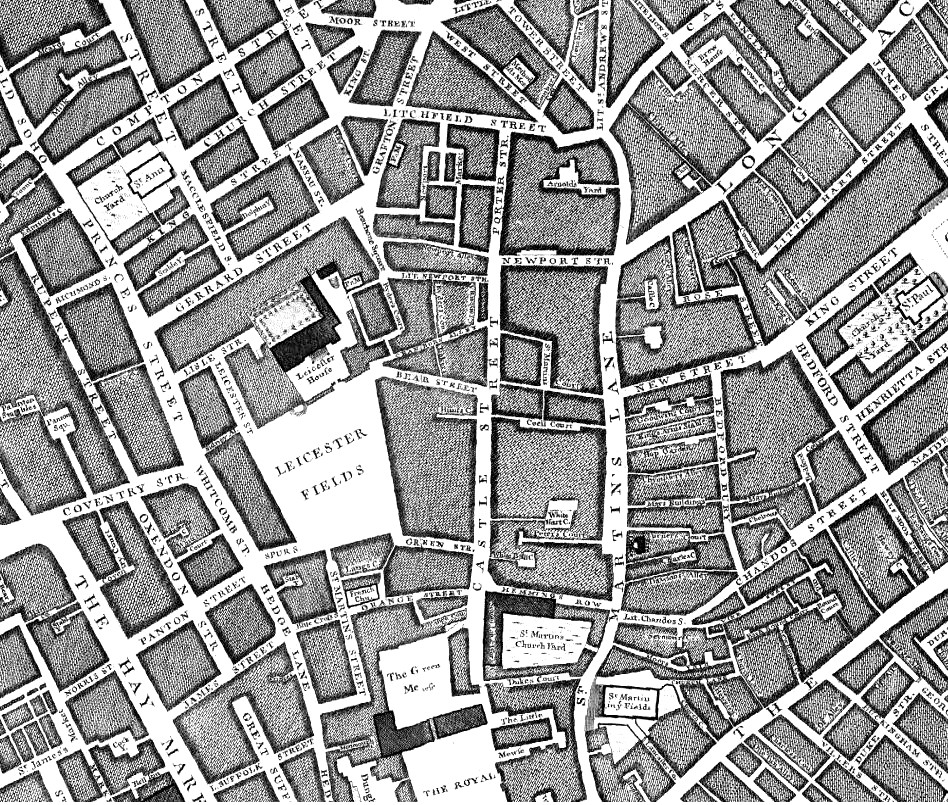

Continuing south, there was no single street running the future route of Charing Cross Road. It was a maze of streets, alleys and courts. In the following extract from Rocque’s map, the future location of Cambridge Circus is in the middle of the top edge of the map, and the future location of Trafalgar Square is at The Royal Stables in the middle of the lower edge of the map.

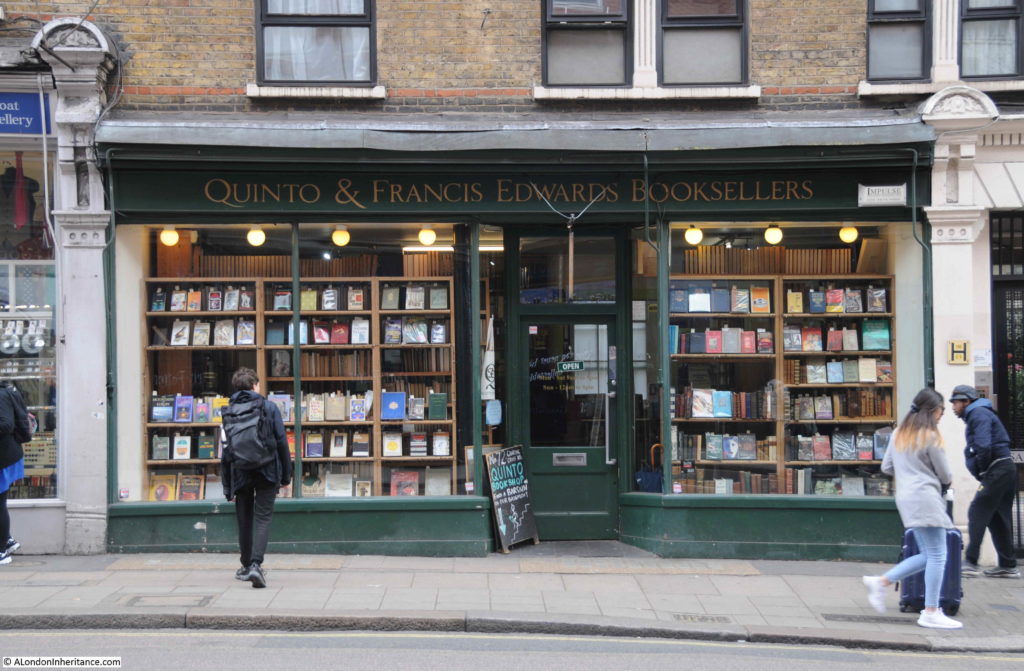

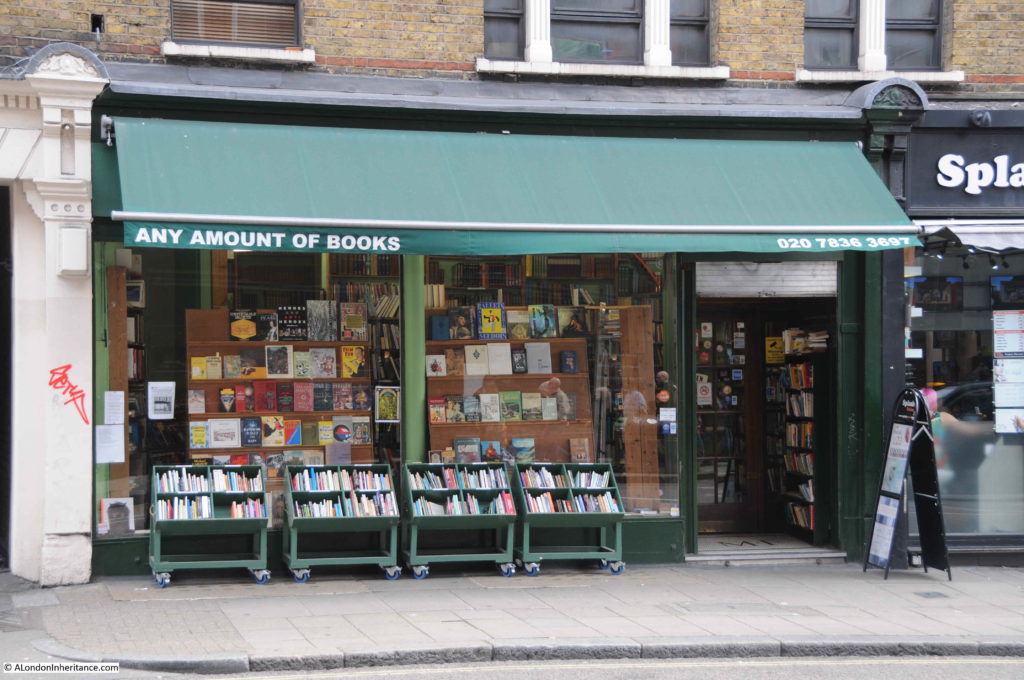

Charing Cross Road has long been known for bookshops. The most famous being Foyles at the northern end of the street, but with many other specialist, new and second hand bookshops lining the street as you walked south.

Many of these have closed over the years, but thankfully a few still remain, holding out against the wave of standardisation across London streets.

Other shops that fill the retail units along the ground floor of Sandringham Buildings.

The development of Charing Cross Road to a single street from Tottenham Court Road towards Trafalgar Square, and the development of Sandringham Buildings can be told through the story of Newport Market.

From the time of Rocque’s map, up to the mid 19th century, the area from what was Hog Lane, around what today is Cambridge Circus, and part of what is now Charing Cross Road to the south was a dense cluster of streets and buildings known as Newport Market.

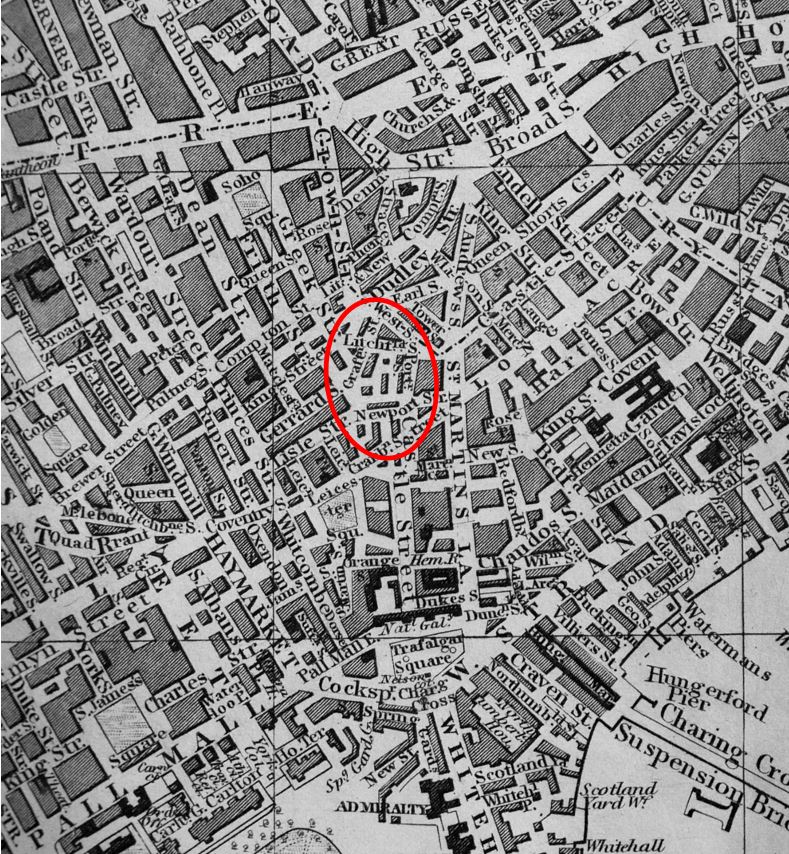

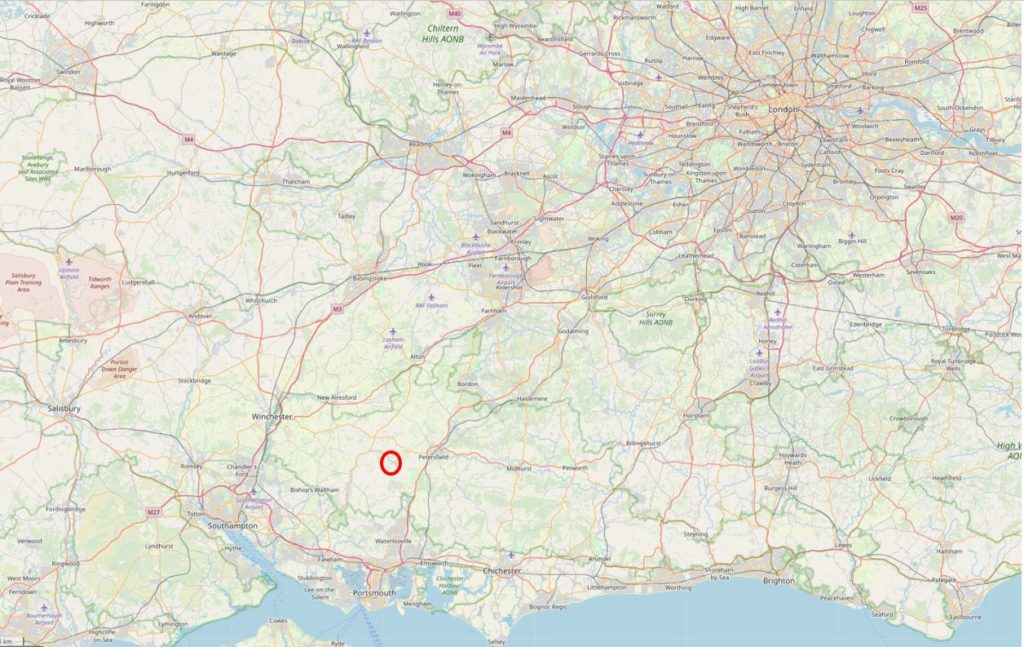

In the following extract from Reynolds’s 1847 “Splendid New Map of London”, I have circled the area of Newport Market with a red oval. To the north is Crown Street, the new name for what was Hog Lane, and the street that will become the northern part of Charing Cross Road.

Trafalgar Square has replaced the Royal Stables, but there is no single, direct street continuing from Crown Street down towards Trafalgar Square.

In 1654, Lord Newport purchased a block of land, which today covers the area from Little Newport Street up to the location of Cambridge Circus. He built a large house and gardens, which would remain until 1682 when the estate was sold and the house demolished. The land was then redeveloped by Dr. Nicholas Barbon who created Newport Market which consisted of a large central square and operated as one of London’s main meat markets.

By the mid 19th century, the area had degenerated considerably and was recorded as providing slum living conditions. An article in the London Evening Standard of the 26th August 1880 titled “Old Newport Market” records how the market had changed:

“Gone are the glories of Newport Market; gone the glory of its Butchers-row. Fashion has this many a year forsaken its uninviting neighbourhood. Beau and buck know no more of its unsavoury haunts. Filth and squalor reign supreme in its courts and passages. Poverty and vice find within its dingy precincts congenial shelter. The old Market, indeed, exists; its walls are still standing. But how changed, how utterly changed, out of all form and semblance. Its shops and sheds are stables and slaughter-houses, its stalls and stands bricked over and built upon. Its very identity is lost; merged, so to speak, in that of prince’s-row, the narrow lane – foul among the foul – that surrounds and gives access to it. Even the name has been taken from it and applied indiscriminately to the adjoining thoroughfare and the unwholesome butchers court that abuts the southern extremity.”

The article then goes on to describe the remaining trades of the market:

“The semblance only, a shadow, as it were, of its former self. A score or so of stalls owned by good-natured Irish women, pipe-loving and rough-tongued. A few eager French women, basket-bearing and garrulous, bargaining for flabby lettuce, unhealthy looking endive and sun-stewed cress. The indescribably nasty row of butchers’; shops in the narrow alley on the right, these constitute the market of to-day, galvanised into fitful activity on Saturday and Saturday night.”

The need for a wide street, linking the junction of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road with Charing Cross and the station of the same name that had opened in the 1860s, was part of the 19th century construction across London of direct, wide streets that would address congestion problems and sweep away what were seen to be dense, slum housing.

Plans for Charing Cross Road developed during the 1870s, but there were challenges with land ownership, how much land could be purchased for the new development and the impact on those who lived in the houses that would be demolished. Newport Market was in the middle of the area planned for the extension and widening of the new Charing Cross Road, and the surrounding development.

Finally in 1882, plans were in place, and purchases of property made along the streets that would be demolished. The Illustrated London News on the 19th August 1882 reported:

“Steps have at length been taken for making, at all events, a beginning of a long-needed public improvement, a new thoroughfare between Charing-cross and Oxford-street. The materials of about forty houses about Newport Market have lately been sold by Messrs. Eversfield and Horne, the structures themselves are in process of demolition, and in the course of another month a large portion of the following streets will have disappeared:- Newport-court, Little Newport-street, Market-row, Market-street, Prince’s-row, Lichfield-street, Hayes-court, and Grafton-street.”

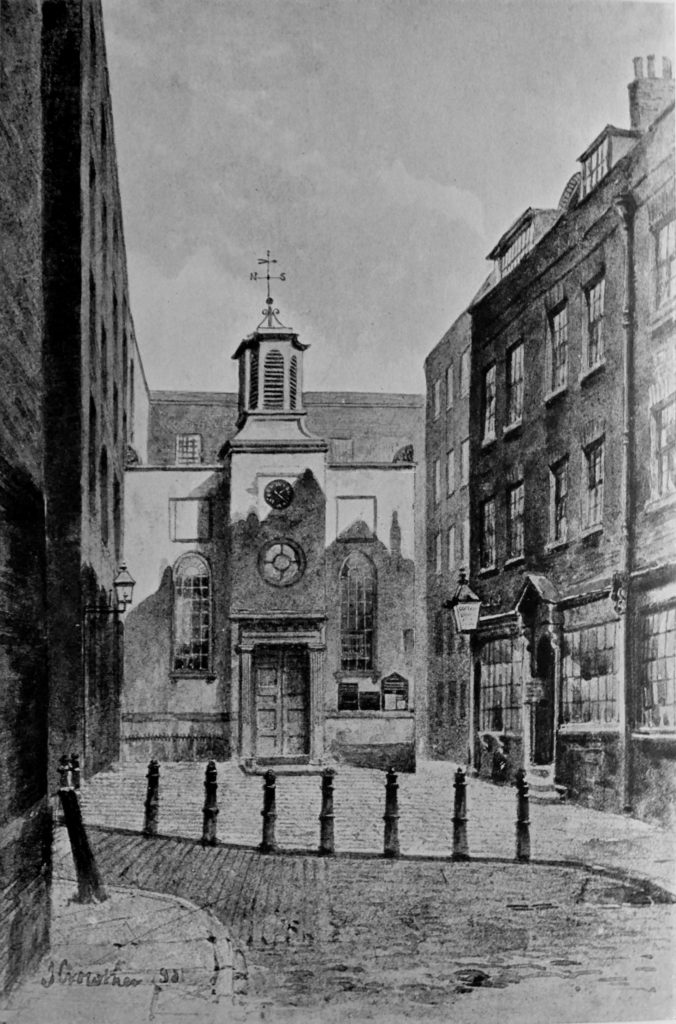

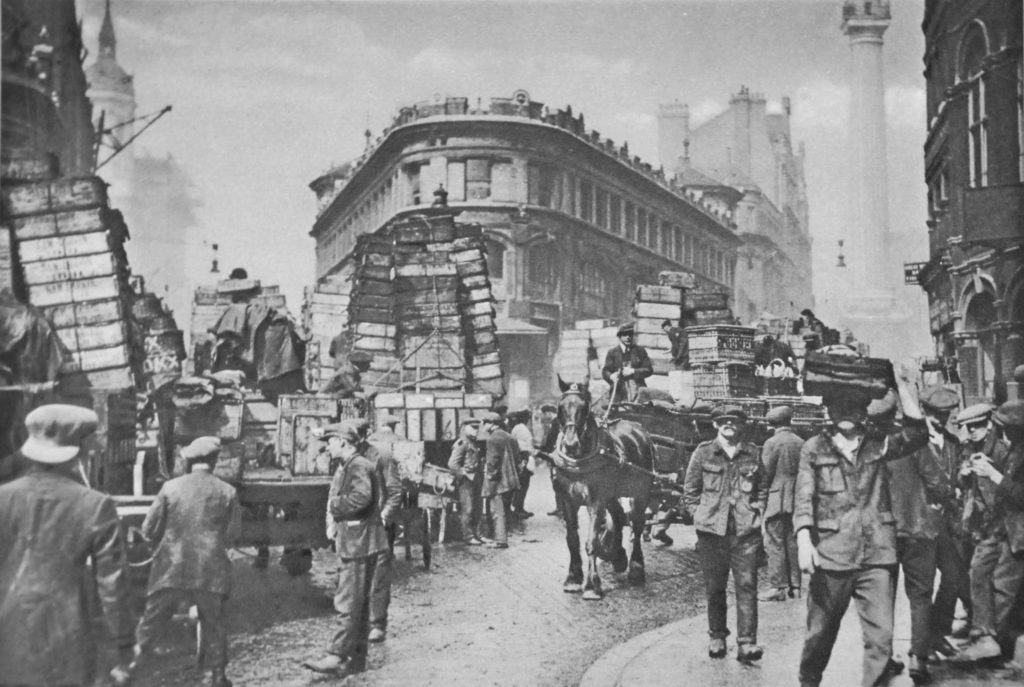

The last mentioned Grafton Street appears in one of the prints made in the early 1880s of Newport Market. The following print titled “North side of Newport Market Soho, Grafton St on the right”. The print is dated 1882, the same year as Grafton Street would be demolished – possibly a 19th century example of recording buildings and streets before their demolition.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PZ_WE_01_0315

The above view shows a rather good looking location. Open space edged by some well constructed buildings with shops along the ground floor. What the area may have been like can be judged by some of the newspaper reports of the time, such as the following from the Illustrated London News on the 10th February 1872, regarding the remains of a statue of King George II in Leicester Square:

“When the statue was removed, having suffered too much ll-usage and some positive mutilation, the effigy of the horse remained, and became the target of frequent stone-throwing practised by the idle boys of Newport-market and its neighbourhood.”

Returning to Sandringham Dwellings, the Metropolitan Board of Works were forced by the Government to construct dwellings for “2,000 people of the labouring classes”, in the area of Newport Market. Agreement to this allowed the Metropolitan Board of Works to commence demolition and the build of Charing Cross Road.

The dwellings for 2,000 people were comprised of the two blocks of Sandringham Dwellings that lined both sides of Charing Cross Road to the south of Cambridge Circus.

As was often the case with these new developments, it was probably not the displaced labouring classed that benefited from the new accommodation.

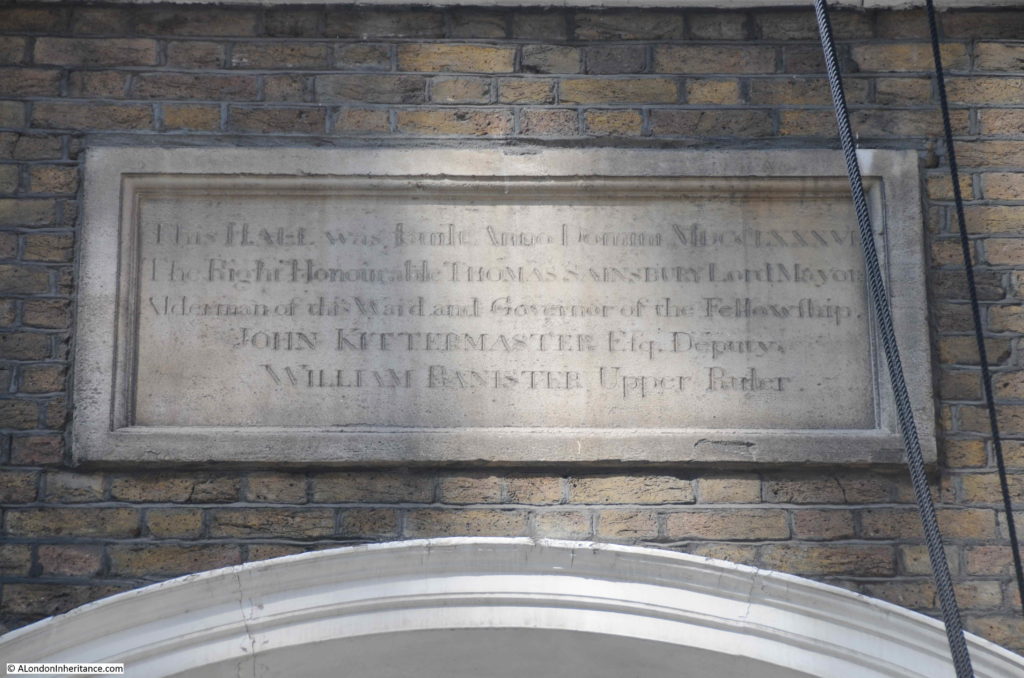

In the 5th September 1885 edition of the Illustrated London News, Police Superintendent J.H, Dunlap of St. James’s Division wrote “On the site of Newport Market, notorious for everything bad and disreputable, have been erected two splendid blocks of buildings for the accommodation of the working classes, one by private speculation and called Newport Dwellings, and the other by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company, called Sandringham-buildings, a suite of erections of handsome elevation, with no appearance whatever of model buildings, having large shops on the ground floor, with the upper portion allotted in suites of two, three and four rooms. There is every possible accommodation and sanitary appliance. In these buildings, the Superintendent adds, he has sixty-seven police families, occupying 193 rooms.”

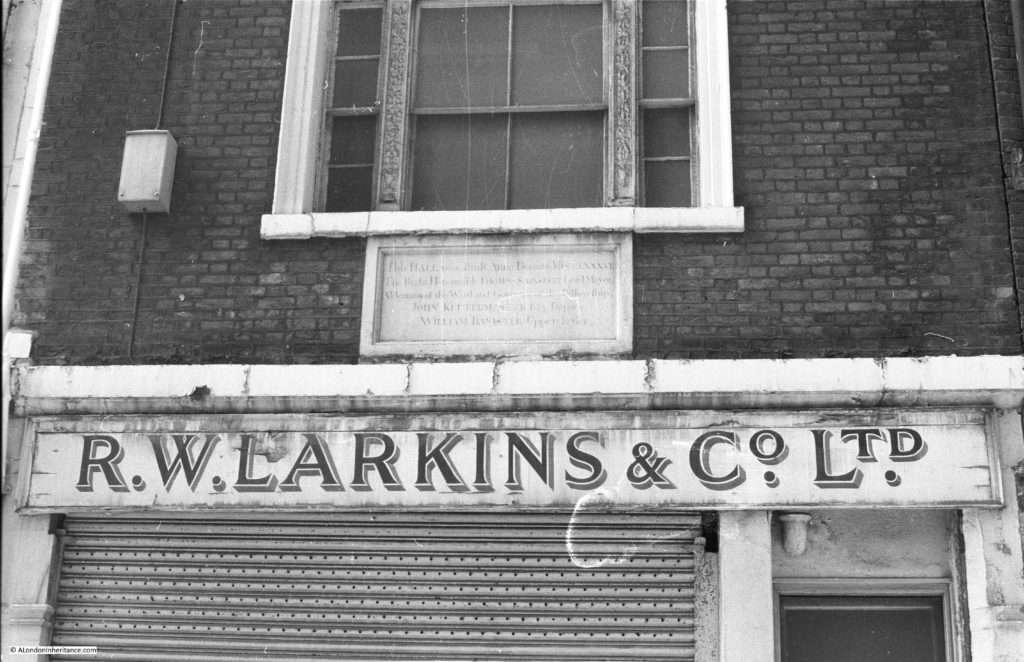

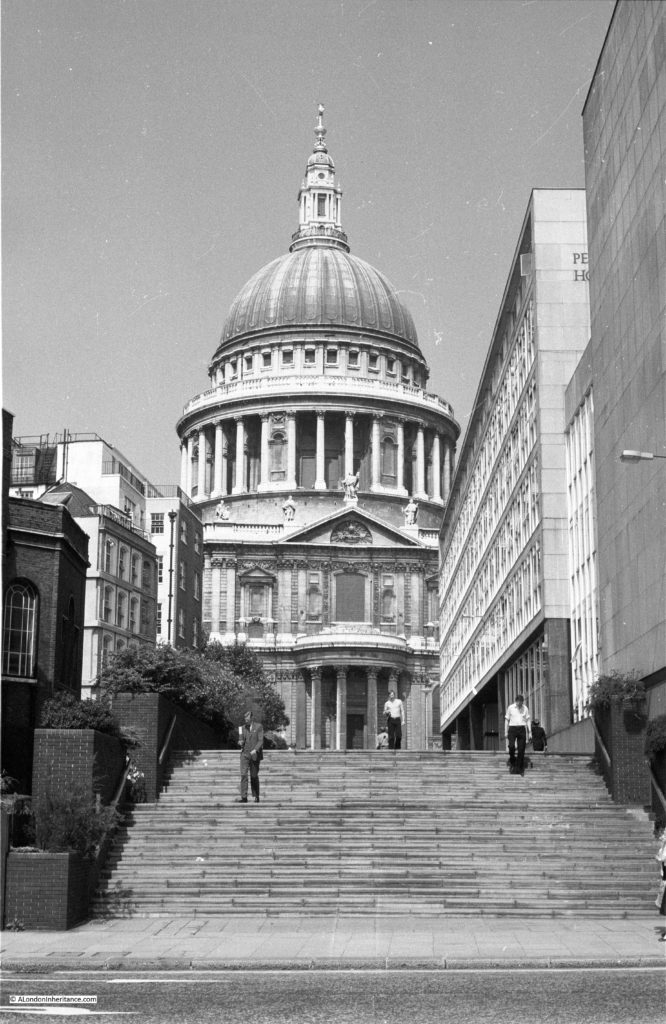

The following view of the remaining block of Sandringham Buildings is from the north, looking south along Charing Cross Road.

To show how identical the remaining block is with the demolished block opposite, compare the corner of the building with the corner photo I had taken in one of the photos at the start of the post.

The name plaque recording that the building was erected by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company can still be seen on the northern corner:

Cambridge Circus is just under half way along Charing Cross Road from the north. It is at the point of intersection with Shaftesbury Avenue. it is named after the Duke of Cambridge who officially opened Charing Cross Road on Saturday 26th February 1887.

The Morning Post reported on the opening:

“The new line of thoroughfare formed by the Metropolitan Board of Works from Charing-cross to Tottenham-court-road, and designated Charing-cross-road, was on Saturday afternoon opened by the Duke of Cambridge. His Royal Highness was at one o’clock met opposite the church of St. Martin-in-the Fields by the members of the Metropolitan Board of Works, and thence drove along the new street to the circus forming the junction of the new thoroughfares.

Crowds had assembled on either side along the whole of the route, and at many points flags were flying from the windows of the houses. Upon reaching the circus the Duke of Cambridge alighted, and addressing those within hearing said – ‘I declare the new thoroughfare – Charing-cross-road – open for public use. I am happy to have the honour of assuring you and the other members of the board that all such improvements as these are of the greatest possible value (hear, hear). there is no question that the growth of this great metropolis has been such that the building of houses east and west through the town has gone on in a manner seriously injuring the public health, and anything the Metropolitan Board of Works or any other body can do to improve the locomotion in such a great city must be a benefit not only to the metropolis but to the country at large (cheers).”

The article also provides some statistics on the new road “The length of the new street is 966 yards, and its width generally 60ft. It widens to about 130ft at St. Martin’s-place but it is restricted at its entrance into Trafalgar Square to 45ft, between St. Martin’s Church and the National Gallery”.

The view across Cambridge Circus towards the Cambridge pub.

The most impressive building facing onto Cambridge Circus is the Palace Theatre, opened in 1891 for Richard D’Oyly Carte who intended the theatre to be the home of English opera and on opening the theatre was known as the Royal English Opera House.

As always, there is so much to see and explore, and I am only touching on a brief part of the history of the street.

The Porcupine pub on the southern corner of Great Newport Street, the building dating from around 1865.

Look on the corner of the building, a boundary marker is partly hidden by the lighting and flowers.

The old Tam O’ Shanter pub:

There has been a pub here since the mid 18th century, originally named the Bulls Head. The new building was part of the realignment and widening of Charing Cross Road and the new building dates from 1896, when the pub changed name to the name that still appears at the top of the building today. The Tam O’ Shanter closed as a pub in 1960.

Charing Cross Road is one of the locations where rumours of a hidden street below the surface persist. In the middle of Charing Cross Road, at the junction with Old Compton Street, there is a large grill on an island in the middle of the road.

Peer down through the grill and you can see a couple of signs for Little Compton Street on the brick wall lining the tunnel.

Personally I am not at all convinced that the wall and street signs are all that remains of a street from before the redevelopment of the area, now hidden below the surface.

For a start, in the 1746 map, Compton Street approaches from the west, and terminates at Hog Lane. In the 1847 map. Compton Street still approaches from the west, then Little and New Compton Street cross over and continue eastwards from what is now Crown Street. The wall below the surface is running north south, in the same direction as Charing Cross Road, not east-west as would be expected if this was a relic of Little Compton Street.

I am also not convinced that street levels along this part of Charing Cross Road changed this significantly during redevelopment to leave a substantial part of a wall buried below ground level.

Finally, the article I quoted earlier from the Morning Post on the 28th February 1887 probably gives the real reason; “A subway has been formed under the whole length of this street to receive the gas, water, and other mains, telegraph wires, &c.; it is placed under the centre of the carriageway, and is 12ft wide and 7ft, 9in. in height, formed of a semi-circular arch of brickwork.”

I suspect the street names may have been painted on the wall, or recovered from Little Compton Street and attached to the brick wall of the subway so that those working below ground, installing or repairing utility services would know where they were, as they worked their way, below ground, along the centre of Charing Cross Road.

As usual, I have only scratched the surface of the history of the area I visit to track down the location of our old photos of London. In a post a few years ago I wrote about Foyles and the College for the Distributive Trades to the north of the street.

Newport Market has long disappeared beneath Charing Cross Road and the buildings that now line the street, but the name can still be found in Newport Place, Little Newport Street and Great Newport Street – all references to Lord Newport who purchased the land in 1654 and who also gave his name to the market.