Curious London was the title of a small book published in 1951 by Hugh Pearman. The author was a London Taxi Driver and in the book there are two pages for each of the “twenty-nine boroughs and cities that make up the county of London”. I have already hunted down the Southwark sites from the book, and for this week’s post I went on a walk to find the six locations Pearman covered in the book for Curious Battersea.

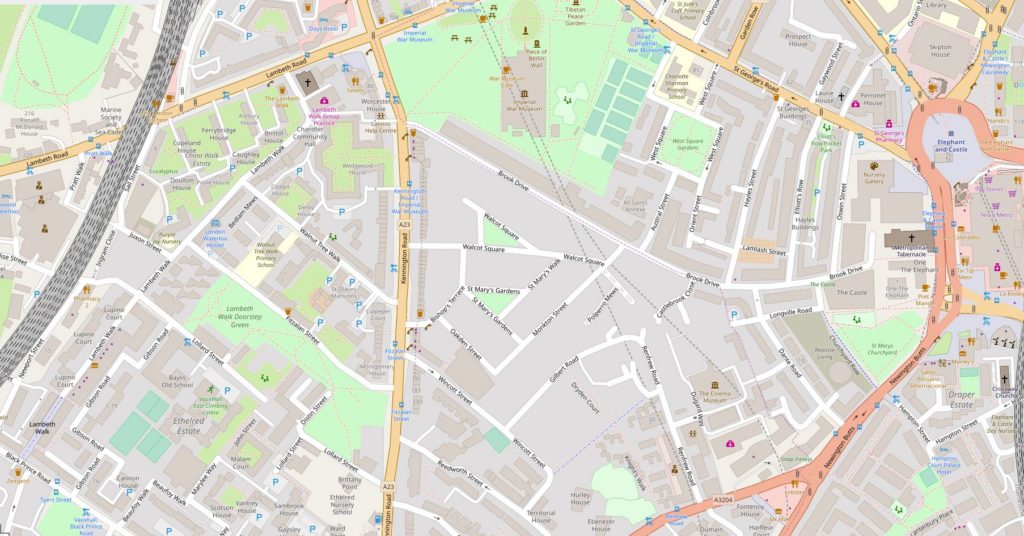

I have shown the locations on the map below. They are numbered differently to the order in which they appear in the book. I started at Clapham Junction and walked to Battersea Power Station and changed the site ordering to better fit my walk.

Map © OpenStreetMap contributors.

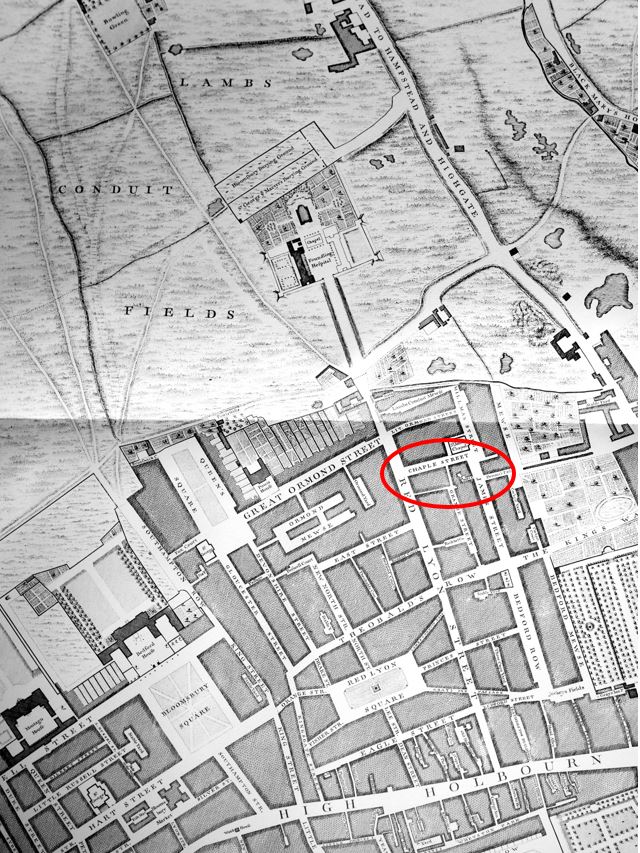

The first location was a problem before I set out on the walk. At the time little did I know it was not so far from Clapham Junction Station.

Site 1 – “Down by the railway tracks, hemmed in by streets of little houses, is this caravan encampment. Some of the dwellers in the old vans claim to be of pure Romany stock. Their ancestors came, so they say, year after year in the long ago when all around was Surrey countryside”.

This was Pearman’s caption to the photo below:

I failed to find the possible location of Pearman’s photo before walking the area. There are no clues in Pearman’s book. I have subsequently found a possible location as Sheepcote Lane which I have marked as point 1 on the map.

One side of Sheepcote Lane is of terrace housing and on the other side of the street is a grassed area between the road and the railway tracks, so as Pearman describes as being “down by the railway tracks” this could be the location.

I found the reference to Sheepcote Lane in a presentation by Dr. David M Smith of the University of Greenwich titled Gypsies and Travelers in Housing: adaptation, resistance and the reformulation of communities., which refers to Sheepcote Lane being occupied in the 50s, which is the same time period as Pearman’s book.

I will need to return to photograph the street and update this post.

The first location that I could identify in Curious Battersea was a walk from Clapham Junction station down to Battersea High Street to find:

Site 2 – “In the High Street is this 17th century bow-windowed inn, the ‘castle’, a picturesque reminder of coaching days.”

A pub has been on the site since the very early 17th century. Pearman’s text claims that the building in his photo is the 17th century Inn, however I am not sure that all the features are from the original pub. Features such as the bow window may have been retained, but the facade does look of later construction.

There is what appears to be a large crest on the front of the pub, facing the camera. The small photo in the book does not provide any detail on the crest.

The pub did not last for too many years after Pearman’s book. It was demolished in the 1960s along with the buildings to the left and right of the pub. New flats were built to the left and a new pub (retaining the Castle name) was constructed on part of the site of the original Castle and slightly to the right.

This 1960’s Castle pub was demolished in 2013 and the site is now occupied by flats:

Checking the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, the Castle as photographed by Pearman was mainly on the site of the new flats, but also on part of the 1960s flats to the left in the photo below.

I was not aware that it was there, but found after walking the area, that the 1965 plaque from the 1960s pub is on the wall of the new flats – the wall that faces onto the open space on the ground floor on the 1960s flats to the left. The plaque records that the original Castle was built circa 1600 and rebuilt in 1965. The plaque also records that in 1600, mild ale was 4 shillings a barrel (equivalent to 1/4 d (old pence) a pint) and in 1965 was 1 shilling and 5 pence a pint.

Another reason to return to Battersea and photograph the plaque.

The London Metropolitan Archives, Collage site has a photo of the Castle in 1961, just a few years before demolition.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0965_62_255

Although I missed the 1965 Castle plaque, I did find some other interesting features in Battersea High Street.

This three storey building is occupied by the Katherine Low Settlement.

The plaque on the first floor records the Cedars Club, founded in 1882 and rebuilt in 1905, whilst the blue plaque to lower left records Katherine Mackay Low, 1855 to 1923, a philanthropist in whose memory the settlement was founded on the 17th May 1924.

Katherine Mackay Low was born in Georgia in the USA to British parents. When her mother died in 1863 her father returned with his family back to UK, and when he died, Katherine settled in London. Her father was a merchant and banker so her inheritance was probably the source of her independence and philanthropy.

The land occupied by the Katherine Low Settlement was originally part of the grounds of the vicarage of the Vicar of Battersea (the large building, part of which can just be seen to the left of the above photo). The railway cut through the grounds of the vicarage in 1860 and due to this disruption the vicar moved out of the house.

In 1872 the old vicarage building was occupied by a settlement established by two Cambridge colleges. The purpose of the settlement was the support of the poor in the area, which was much needed in this area of Battersea in the latter decades of the 19th century.

The Cambridge colleges settlement established the Cedars as a boys club and mission and in 1905 the three storey building was constructed between the old vicarage and Orville Road.

Katherine Mackay Low died in 1923 and funds were raised to create a legacy in her name. The Cedars building was purchased and the Katherine Low Settlement was established.

The Settlement continues to this day, in the same building as a local community charity.

Whilst researching these posts, I stumble on events of which I was completely unaware. Searching newspapers for the Katherine Low Settlement, there was one date when many newspapers mentioned the settlement, but it was through a disaster rather then the works of the settlement. The first in-flight fire of a passenger flight. From multiple newspapers on the 4th October 1926:

“One of the worst disasters in the history of the Paris-London air lines occurred on Saturday afternoon near Tonbridge, Kent. A big French four-engine Bleriot plane from Le Bourget aerodrome was seen to be in difficulties, and flames were observed coming from the rear. Slowly the great machine turned turtle, and then fell like a stone into a field. Farm workers ran to render help, but so fierce was the heat that no one could approach it, and every soul on board perished.

Mr. J.H. Webb, a butler at an adjoining house, the first man on the scene, said ‘I was in the pantry when I heard the noise of an aeroplane passing overhead. As I looked through the window I saw the machine suddenly burst into flames and nose-dive to the ground. I shouted for assistance and, with some of my fellow-servants, rushed to the spot. Through the roaring flames I saw the terrified features of a woman passenger. We made an attempt to get to the woman’s assistance, but before we could approach her she was totally obscured by flames and smoke. The moment I saw my chance, however, i did succeed in dragging out a lady wearing a silk dress, but I was too late. She was very badly burned and quite dead.'”

The Settlement and Battersea connection comes when the article lists the casualties of the crash, one of whom was Miss Gertrude P. Hall, aged 43 of The Katherine Low Settlement, High-street, Battersea who was described as “a lady of independent means who devoted herself to philanthropic work.”

Gertrude Hall must have been one of those who contributed to the founding of the Katherine Low Settlement just a few years earlier.

I walked further along Battersea High Street and although the Castle has been lost, there is still a pub in the street. This is the rather excellent, mid 19th century pub, The Woodman.

Further along Battersea High Street is the building constructed for the Sir Walter St. John’s School:

Sir Walter St. John of Battersea founded a charity in 1700 for the education of poor boys of the parish. The school expanded over the years with increasing number of boys and the inclusion of girls.

The enlarged school was constructed in 1859 and the school underwent various rebuilds, modifications and upgrades over the following years.

The school became a grammar school after the war, however in the following years the school went through various changes where pupils were integrated with other schools, classes moved and eventually, with a falling local birthrate, the school was closed in 1986.

The buildings were purchased in 1990 by Thomas’s London Day School, one of a group of Thomas’s independent schools within London.

I do not know whether it was due to the growth in numbers, or the desire to separate boys and girls, however in the 1850s the girls from the school were moved to Mrs Champion’s School, and the buildings of this school can still be found in nearby Vicarage Crescent:

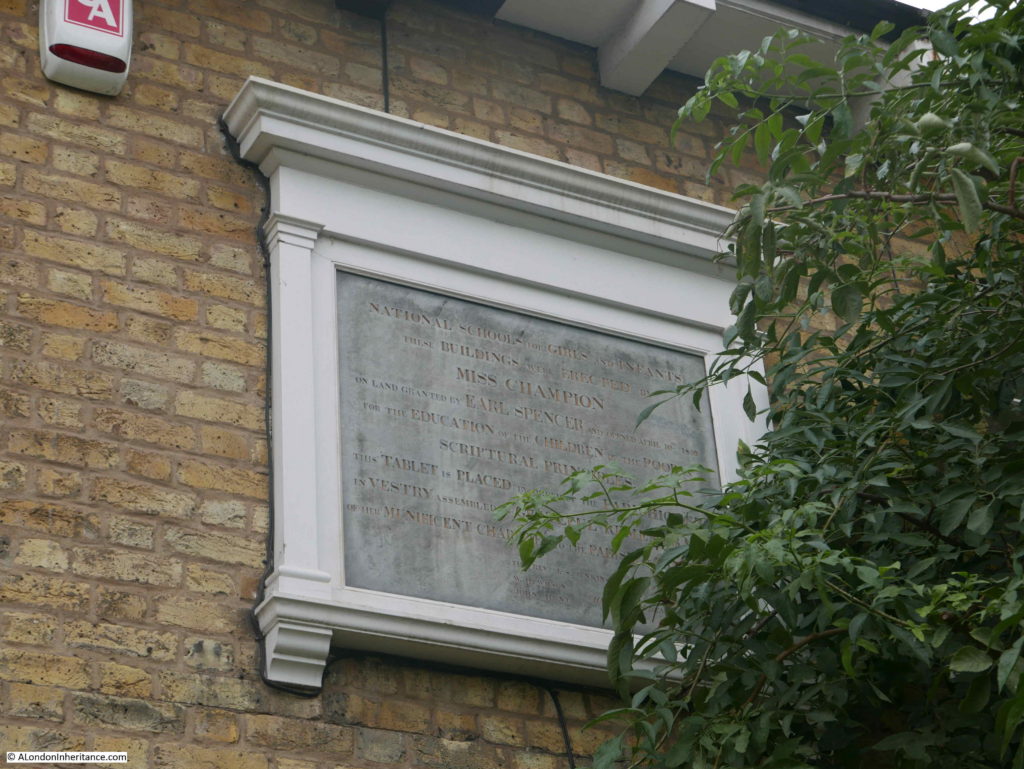

A plaque on the building:

The plaque reads (hopefully read correctly, rather difficult as part of the inscription was hidden by vegetation):

“National School for Girls and Infants. These buildings were erected by Miss Champion on land granted by Earl Spencer and opened April 10th 1855 for the education of the children of the poor on scriptural principles. This tablet is placed by order of the parishioners in the Vestry assembled in grateful remembrance of her munificent charities to the Parish of Battersea.”

To find this school building I had doubled back along Battersea High Street to Vicarage Crescent, but I was still on the correct route as my next location in Curious Battersea was a short distance further along the street.

Site 3 – A different sort of dwelling is this one in Vicarage Crescent that also seems strangely out of place in present-day Battersea. It was designed by Wren and has carvings by Grinling Gibbons. Although the home of a private family, this house, one of the finest in South London, is at certain times open to the public and is well worth a visit.

This is Grade II listed Old Battersea House. The house is set behind a high wall and faces the River Thames across Vicarage Crescent and the grassed area directly in front of the river.

I photographed the house from beside the river, looking across Vicarage Crescent.

Pearman’s photo appears to be taken from the side, probably as with my photo it is not an easy house to photograph from the front. The original photo also appears to show a building on the side of Old Battersea House, between the house and the small side road that leads to the estate at the rear.

This extension is not there today, with just what I assume to be the original Old Battersea House as shown in the photo below (with a bright sun shining directly into the camera).

The house was originally called Terrace House. It became derelict in the late 1960s and restored in the 1970s – it was perhaps then when the extension photographed by Pearman was removed.

If you have a spare £10 million, the house is currently for sale.

Between Vicarage Crescent and the River Thames opposite Old Battersea House, there is a small grassed area, where this lovely sign can be found.

I do not know when these signs date from, but there are still a few to be found. I like the depiction of the river at the bottom of the sign with the Thames sailing barge on the right – signs should be more like this, graphical and including a symbol of their subject.

To get to the next location in Curious Battersea, I continued east along Vicarage Crescent, along Battersea Church Road to:

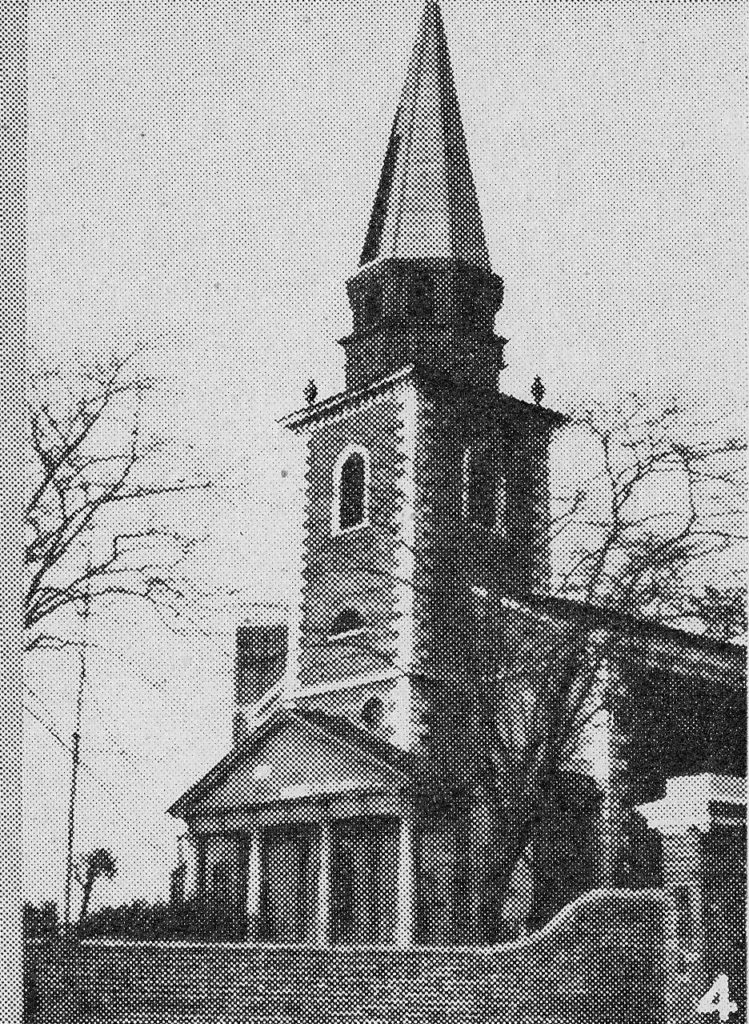

Site 4 – By the river is this parish church of St. Mary’s, a church full of memories. Here are a few of the famous names with which it is connected :- William Blake, poet, artist and mystic, here married his wife Katherine: from the upper vestry window Turner painted his glorious sunsets. The great Wilberforce, whose house was in the parish boundaries was a frequent visitor to the church. Buried in the crypt are the remains of that infamous “turncoat” General Benedict Arnold who tried to betray his comrade-in-arms, George Washington to the British.

St. Mary’s is a lovely church, facing at a slight angle onto the river, the church has always struck me as being perfectly in proportion to its surroundings. The lighting was perfect as I walked towards the church along Battersea Church Road, where the church suddenly comes into view after a bend in the road.

At the church gates. The church sits on a slightly raise plateau of land as can be seen in the following view.

The current St. Mary’s Battersea was built between 1775 and 1777 to a design by the architect Joseph Dixon. As with so many other London churches, the location had already been the site for a church, possibly as far back as the 9th century.

Although the church today dates from the 18th century, it was repaired and reconstructed in 1878 and 1938 with later additional repairs.

The church is deservedly Grade I listed.

I had planned to look inside the church, however on the day of my visit there appeared to be a function in the church with a number of cars parked in front – another in the growing number of reasons to re-visit Battersea.

The front of the church with the encroaching towers of flats expanding along the Thames in the rear.

The next location was in Battersea Park which was the perfect excuse for a walk along the river.

The view from the southern side of the river, the shell of the old Lotts Road Power Station stands out, one of the original Chelsea Wharf buildings on the right and yet another glass tower dwarfing its surroundings on the left.

The light was perfect for the Albert Bridge:

On reaching Battersea Park, I walked to the next destination in Curious Battersea:

Site 5 – In the days when this borough still had a countrified air, this old wooden hut was the pavilion of the town cricket club. It is in Battersea Park near where it is said the “Iron Duke” fought a duel with Lord Winchelsea.

It is still possible to feel a “countrified air” in parts of Battersea Park today, as this carefully framed view of the pavilion today demonstrates.

I have no idea if the current cricket pavilion is in the same position as the one in Pearman’s photo, however the pavilion has been considerably upgraded since 1951.

Pearman mentions a duel between the Iron Duke and Lord Winchelsea. The Iron Duke was the Duke of Wellington who at the time of the duel (March 1829) was Prime Minister of Great Britain and Ireland.

The cause of the duel appears to have been the Catholic Relief Bill passed by Wellington’s government. The aim of the bill was to provide greater Catholic emancipation and the possibility of Catholics becoming members of Parliament.

Although Wellington was not a Catholic, fears of rebellion in the country appears to have influenced his decision to support the bill, however he was fiercely opposed by the staunch Protestant, the Earl of Winchelsea. In his opposition to the bill the Earl of Winchelsea appears to have accused the Duke of Wellington of allowing Popery to become part of the State.

Wellington challenged Winchelsea to a duel, which then took place at Battersea.

The duel appears to have been rather a strange affair, more about maintaining gentlemanly honour rather then attempting to kill or wound. Newspaper reports on the 27th March 1829 carried lengthy reports of the build up to, and the actual dual:

“Lord Winchilsea, it appeared, was aware that he had treated the Duke unfairly, and that an apology was due from him, but he considered that as a man of honour, it was ungentlemanly to do an act of injustice, until he had compelled his Grace to adopt a measure which might cause the death of Lord Winchilsea, to be produced by an act of the Duke’s. However monstrous the system may appear in theory, it is considered the very perfection of honour, and the Duke of Wellington was forced to discharge his pistol at Lord Winchilsea. The ball fortunately did no mischief, and then his Lordship tendered such an explanation as was deemed satisfactory, and which was prepared to be presented , in case the affair had terminated fatally to Lord Winchilsea. The latter nobleman was conscious that he had injured the Duke, and had determined therefore, not to return his fire.”

Both parties maintained their honour, and no one was wounded or injured. I suspect that both parties were also concerned that if the Duke had been killed, political chaos would have ensued and if Winchilsea had been killed he would have become a martyr to the Protestant cause.

There does not appear to be any monument or plaque to the duel in Battersea Park, however on the Cricket Pavilion there is a plaque recording another 19th century event:

Prior to 1864 the game of football did not have a consistent set of rules to manage the game. There was pressure to develop rules that would apply to all games and in October 1863 the Football Association was formed, who then went on to draw up the 13 rules of Association Football.

To demonstrate the new rules a game was organised on the 9th January 1864 in Battersea Park between two teams led by the FA President and the FA Secretary. The President’s team won 2-0.

Leaving Battersea Park, I then headed to the final location of Curious Battersea:

Site 6 – Not all of interest in Battersea is of the past, as witness this huge ‘Wellsian’ river-side power station. It is one of the largest in the world, and at night, when it is flood lit, has an unearthly sort of beauty.

When Hugh Pearman wrote Curious London in 1951, Battersea Power Station was becoming the largest provider of power to London. Half of the station (the A station) had been completed in the 1930s and construction of the B station started after the war, with the station coming on stream between 1953 and 1955.

In Pearman’s Curious Battersea, the power station was therefore the peak of modernity. Powering London into the future and “at night, when it is flood-lit, has an unearthly sort of beauty”.

Change is continuous and what had at the time been the most thermally efficient power station in the country eventually lost that efficiency. Generation was moving more towards gas and nuclear rather than coal and power stations were moving out of central London down towards the Thames estuary.

Battersea Power Station ceased operation in 1983, and since has been reduced to the outer walls, through many different schemes and ownership and is now finally being rebuilt.

The turbine halls will consist of shops, restaurants, cafes and cinemas and offices will occupy the boiler house.

Pearman’s photo was from across the river, however I wanted to take a look close up.

After walking under the rail tracks that run across the river into Victoria Station, the first of the new apartment blocks that will almost enclose the old power station is on the right. This follows the standard design seen all across London of apartments above and restaurants, bars and cafes on the ground floor.

The old power station with its rebuilt chimneys is still a major construction site with cranes rising above the building.

I am not sure what Hugh Pearman would think of what is happening to Battersea Power Station today. In 1951 it was supporting the growth in post-war electricity consumption across the city. Today the site is mirroring so many other developments across London and whether the old power station retains any historical significance among the glass and steel apartment towers and the commercialisation of semi-public space remains to be seen.

As usual, I feel I am just scratching the surface of the history of the streets I have walked, but again I am grateful to Hugh Pearman for providing another fascinating route through London to discover more about Curious Battersea.