One of the things that makes walking the streets of London so enjoyable is a discovery that not only informs about a building or location, but also tells a whole new story about a period in time and what was changing and important in the life of Londoners at that time.

Walk down Queen Victoria Street towards Blackfriars. After passing the church of St. Benet, Paul’s Wharf on your left you will walk past what, at first glance, appears to be a very bland and utilitarian building.

This is the Faraday Building, named after Michael Faraday, an English scientist who experimented with electromagnetism, demonstrated how rotating a coil in a magnetic field could generate electricity and developed the “laws which governs the evolution of electricity by magneto-electric induction”.

The General Post Office (GPO) opened the first London telephone exchange on this site in 1902 with the existing building being completed and officially opened in 1933 to accommodate the very significant growth in telephone services across London. It was designed by A.R. Myers, an architect of the Office of Works who was responsible for the design of a considerable number of Telephone Exchange buildings and Post Offices across the country.

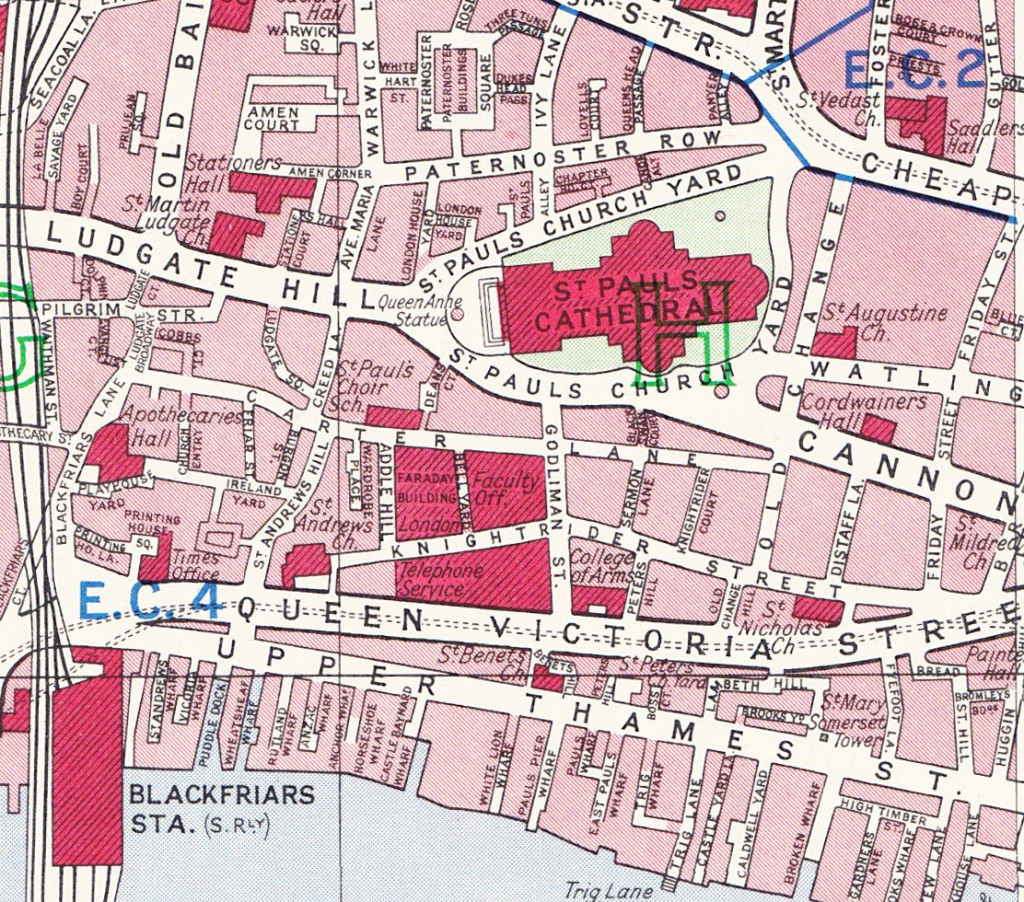

Following completion, the height of the building was very controversial as it blocked the view of St. Paul’s Cathedral from the river. It led to the planning regulations and by-laws that protected sight-lines to the cathedral and restricted the height of buildings. To this day along Queen Victoria Street, the Faraday Building is still the tallest between cathedral and river, as can be clearly seen in the following photo where the Faraday Building is on the right, well above the surrounding buildings.

The Faraday Building was the main telephone exchange for London and also the hub for international circuits with the majority of international calls being routed via the manual switchboards in the building.

Look just above the line of the second set of windows and in the position associated with a key stone, there are a series of carvings, one above each window, that tell the story of what was state of the art telecommunications at the time the building was constructed.

Walking down towards Blackfriars, the first carving is the Telephone.

This type of telephone at the time, was cutting edge technology. It utilised a dial that sent pulses to the telephone exchange when the dial was released from the chosen number position, to tell equipment at the exchange what number was being dialled. Prior to the use of a dial, all calls were put through manually, requiring an initial conversation with an operator which would then start a series of manual patching to put you through to your destination. A technique that worked when few people had telephones, but a model that could not cope with the growth of telephones as the 20th Century progressed.

This type of telephone at the time, was cutting edge technology. It utilised a dial that sent pulses to the telephone exchange when the dial was released from the chosen number position, to tell equipment at the exchange what number was being dialled. Prior to the use of a dial, all calls were put through manually, requiring an initial conversation with an operator which would then start a series of manual patching to put you through to your destination. A technique that worked when few people had telephones, but a model that could not cope with the growth of telephones as the 20th Century progressed.

The next carving shows a series of coded pulses crossing a disk, possibly a representation of the world.

Coded pulses were the means by which information was transmitted about the call to be made. When a dial was turned on a telephone, the release of the dial would cause it to return to its original position and as it returned it would open and close an electrical contact thereby sending pulses to the telephone exchange.

I have seen a number of interpretations for the next carving, but to me these are very clearly the cables that carry telephone signals. There is an outer loop of cable and within the centre, the ends of the cables which have their protective sheath cut back leaving the individual conductors within exposed.

Cables were the key part of the telephone system that carried the pulses and speech from telephones, to the exchanges and then across to their destination, whether in the same street or across the world. (I can see the architects were trying to tell a story in stone of the technology of how a telephone call was made)

Cables were the key part of the telephone system that carried the pulses and speech from telephones, to the exchanges and then across to their destination, whether in the same street or across the world. (I can see the architects were trying to tell a story in stone of the technology of how a telephone call was made)

The next carving shows a Horse Shoe Magnet. Magnetism was key to the telephone system from the very beginning through to the late 1990s when telephone exchanges driven by magnetic devices were replaced by computer based systems.

Michael Faraday’s work with electricity and electromagnetic induction was critical in the understanding of electricity and magnetism, their relationship and laid the foundations for their future practical application. This work was crucial to enable the technology that would go on to provide the telephone systems that spanned the world to be developed and these carvings clearly seem to be celebrating this fact, and the position of the Faraday Building as a hub in this global network.

One of Faraday’s experiments involved rotating a coil of wire between the poles of a horseshoe magnet which resulted in the generation of a continuous electric current in the wires of the coil. This was the first electrical generator and the fundamentals are the same in the generators of modern-day power stations.

We then come to a carving for King George V, the monarch at the time of the construction and opening of the Faraday Building.

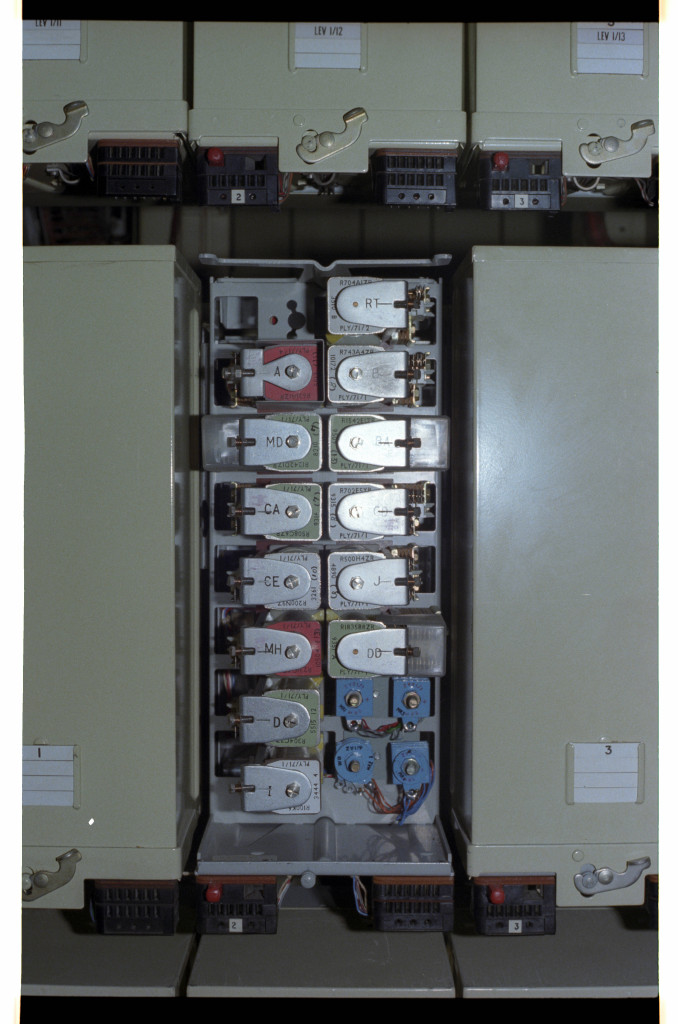

Moving on we come to the carving of an electromagnetic relay which to me is one of the most unique relatively modern-day carvings you will find across London. It is of a core bit of technology, hidden away in the depths of a telephone exchange, but without which automatic telephone exchanges would not have functioned. This type of relay was cutting edge at the time the building was planned, equivalent to the technology that connects the Internet today and switches information from your computer or smart phone through to web-based services across the world.

As an apprentice in the late 1970s with Post Office Telephones (as it was prior to changing to British Telecom and being privatised) I have spent many hours cleaning and adjusting these relays to keep them working and driving the equipment that switched telephone calls. The following photo shows a typical item of equipment from a telephone exchange in the late 1970s full of the relays found carved on the Faraday Building. This is looking end on, as if we were looking at the carving in from the right.

Large telephone exchanges such as that within the Faraday Building would have had many thousands of these relays.

Large telephone exchanges such as that within the Faraday Building would have had many thousands of these relays.

I find these carvings fascinating. They show a pride and celebration in the technology of the time and the function of the building. The majority of buildings constructed during the last few decades, apart from transient corporate logos, tend to have no indication of their function or purpose.

One final set of details can be found just above the main entrances to the building. Just above the door, between the words Faraday and Building is the caduceus (staff with wings above two coiled snakes) of Mercury, the messenger of the Gods, and just above the window there is a carving of Mercury.

Technology has moved on considerably since the Faraday Building and these carvings were completed and I doubt the architect and builders of the time could have dreamt of the Smart Phone and Internet.

I hope these carvings remain for many decades to come to show future generations the pride that they had in the service that the Faraday Building would provide to London.