The Regents Canal stretches from the River Thames at Limehouse Basin to meet the Grand Union Canal just north of Paddington Station, at the area known as Little Venice. The stretch of the canal before it joins with the Grand Union runs alongside Blomfield Road, and it was from the Edgware Road end of Blomfield Road that my father took the following photo, looking along the Regents Canal in 1951.

The same view in July 2018:

The photos are 67 years apart, and the view, whilst basically the same, has some significant differences. Blomfield Road is to the right of the photo with Maida Avenue running along the opposite side of the canal.

In 1951 the Regents Canal was still a working waterway. My father’s photo shows a clear canal (apart from a single boat), along with an unobstructed tow path. In 1951 Blomfield Road was clear, however today, as with the majority of all London streets, Blomfield Road now has parked cars running the length of the street.

This length of the canal is now occupied by private moorings, so it is not possible to walk the tow path along the Blomfield Road stretch of the canal. Boats line the canal, with domestic paraphernalia alongside the boats with the stretch of the tow path immediately alongside Blomfield Road now occupied by a considerable amount of planting.

In the 1951 photo there are curved metal supports running from the railings down to concrete blocks. These are not immediately visible in my photo above, however walk alongside the railings and peer over and the same metal supports and concrete blocks can still be seen in the undergrowth.

My father took the photo a short distance along Blomfield Road from the junction with Edgware Road. It was at the point where a walkway leads off to the tow path.

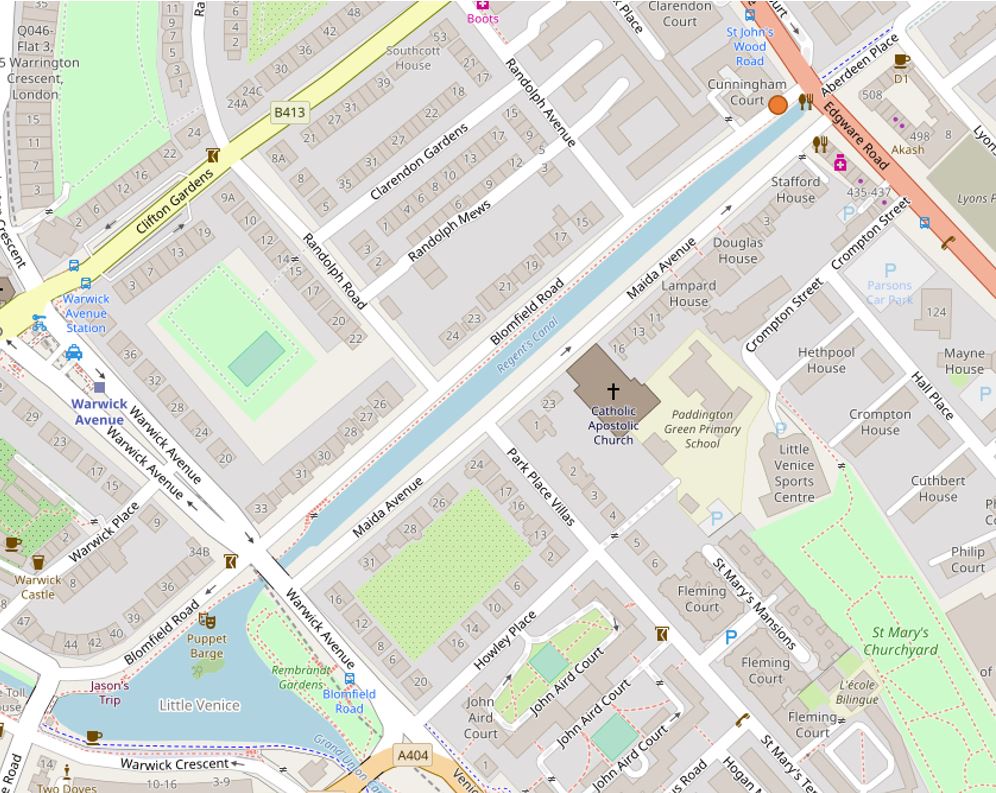

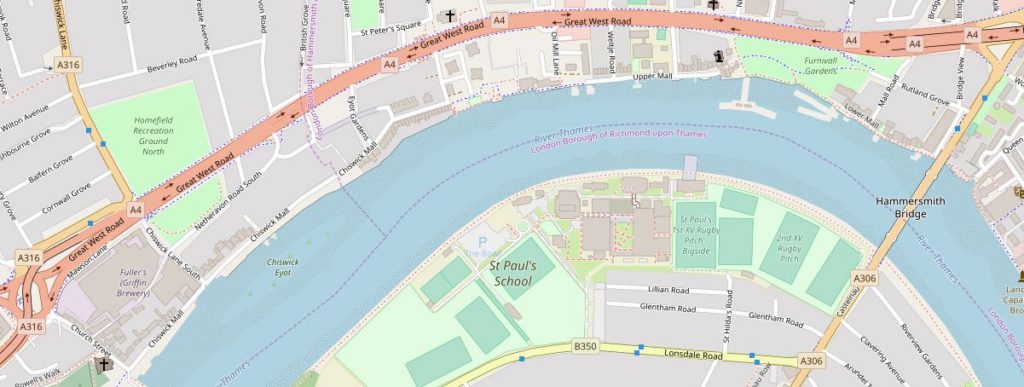

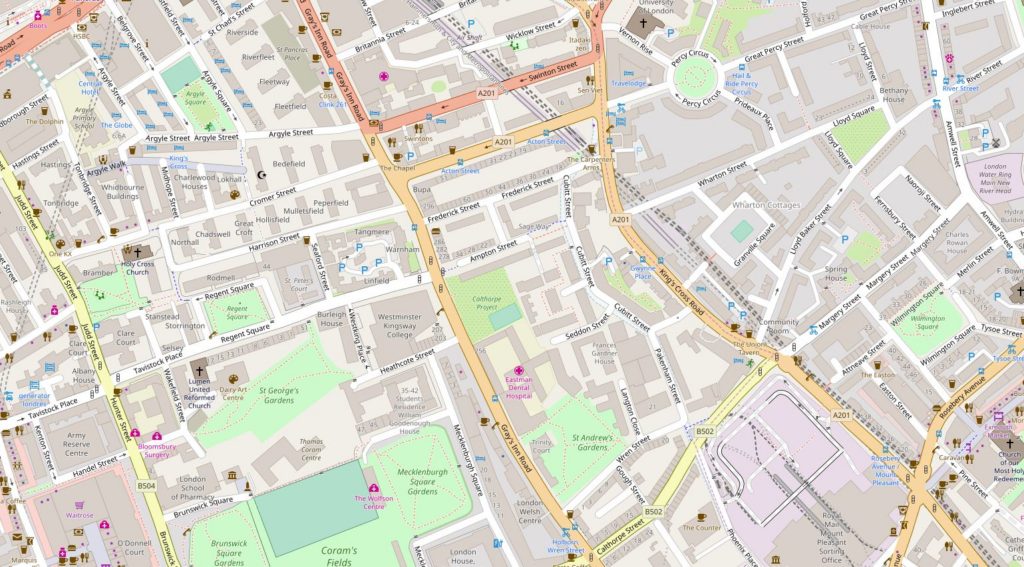

The orange circle at the top right of the following map shows the location. (Map “© OpenStreetMap contributors”).

The photo below shows from where the 1951 and 2018 photos were taken – as best as I can judge, the original photo was taken just to the left of the tree, looking along the canal.

The location is close to where the Regents Canal enters the Maida Hill Tunnel:

The Maida Hill Tunnel is 248 meters long, running to the east under Aberdeen Place. It is only wide enough for a single boat, so care is needed to check that the tunnel is clear before entering. Fortunately the tunnel is completely straight so checking to see if the tunnel is clear is down to whether you can see light at the far end (or hopefully another boat’s lights at night).

The tunnel does not have a tow path, so horses pulling barges along the Regents Canal would have been walked between tunnel entrances above ground, with those on the barge propelling it through the tunnel by lying on their backs and using their feet on the walls of the tunnel to “walk” the barge through the tunnel.

The cafe built above the tunnel entrance provides a rather spectacular view along the length of the canal, however whilst I was there most people seemed more interested in their phones than the view along the canal.

Construction of the Regents Canal started in 1812 from the Grand Union Canal junction, reaching Camden by 1815. The extension on to the River Thames was completed by 1820 at what was called the Regents Canal Dock, now Limehouse Basin.

In the 1951 photo there is a single boat moored to the side of the canal. A close up reveals a rather formal group on the boat. This may have been one of the early pleasure trips along the canal. Two boys can also be seen walking along the tow path.

When the canal was built, the development of London was spreading north. Building was initially along the Edgware Road, however the development of the Regents Canal was the catalyst for further expansion to the north with Blomfield Road being named by 1841.

Both Blomfield Road and Maida Avenue have some rather impressive villas lining the street. The large number of chimney pots are the same as can be seen to the right of my father’s photo.

An impressive corner plot:

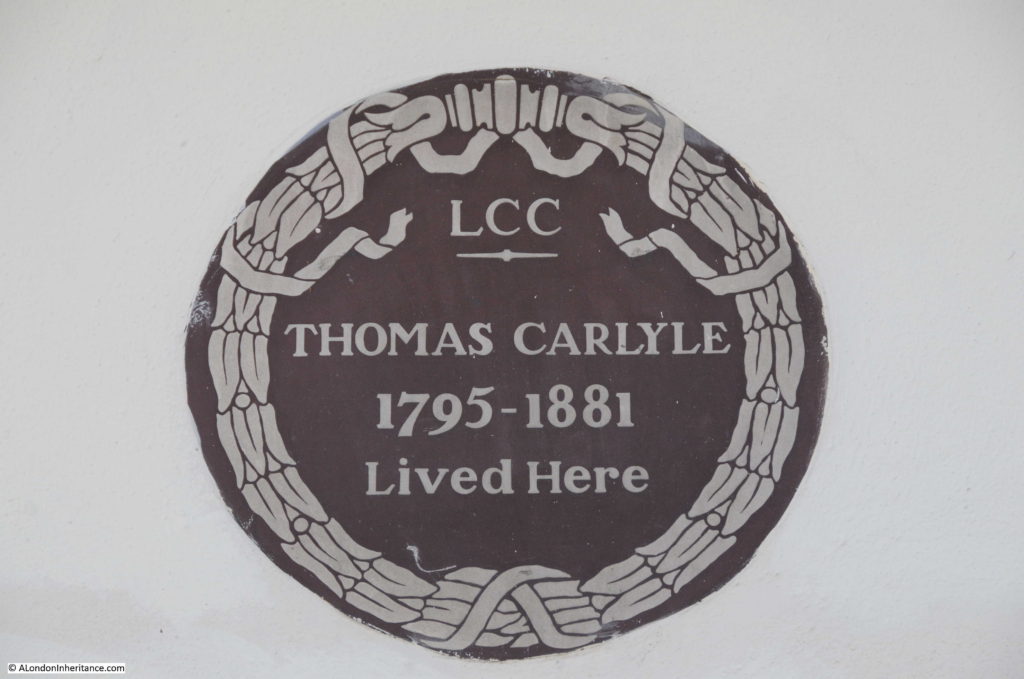

A more traditional, large, three storey town house. The blue plaque informs that Arthur Lowe (Captain Mainwaring of Dad’s Army) lived in the house from 1969 to 1982, the year of his death.

The tow path is now part of the private mooring space with access only for those with a mooring along the canal. Boat owners have set up their own garden space on the tow path alongside their boats.

The boats are very individual, with their internal decoration:

And also their design and external decoration:

The following view is from the Warwick Avenue end of the canal, just before the Regents Canal enters the junction with the Grand Union Canal. The full length of the canal between Warwick Avenue and Edgware Road is occupied by barges and boats, many with two barges to a single berth alongside the tow path.

Where Blomfield Road meets Warwick Avenue there is a bridge that carries Warwick Avenue across the Regents Canal. Through the bridge is the larger expanse of water that makes up the junction with the Grand Union Canal and the branch down to the Paddington Basin.

The next photo is the view from the top of the bridge looking back along the canal with Blomfield Road on the left. The empty canal in my father’s photo now looks very different.

On the railings along the side of the bridge there is a rather nice plaque dating the current bridge to 1907 and constructed by the Borough of Paddington.

I always wonder why my father took the photos from the position that he did. I would have thought that the bridge provided a better viewpoint, however given that the majority of the canal as seen from the bridge was empty in 1951, his photo from the Edgware Road end of Blomfield Road included the boat with the group of people, possibly waiting for a trip along the canal, and the two boys walking along the tow path. It was probably these features that added to the overall composition of the photo.

It also makes me very aware of how photography has changed from when my father had the expense of film and developing of the negatives, so individual photos had to be more carefully considered. Compare this to digital photography today when having paid for the camera and memory cards the cost of photo is effectively zero.

The Regents Canal offers some fantastic walking. I have walked several sections, but never the entire length of the canal – another long walk added to the ever growing list.