The inspiration for this week’s post came when a couple of months ago, a reader e-mailed regarding Bache’s Street, a street a short distance to the north-east of Old Street roundabout.

There was not much initially to find about Bache’s Street. I found some details about the origins of the street, and a tragic murder, but that was about it.

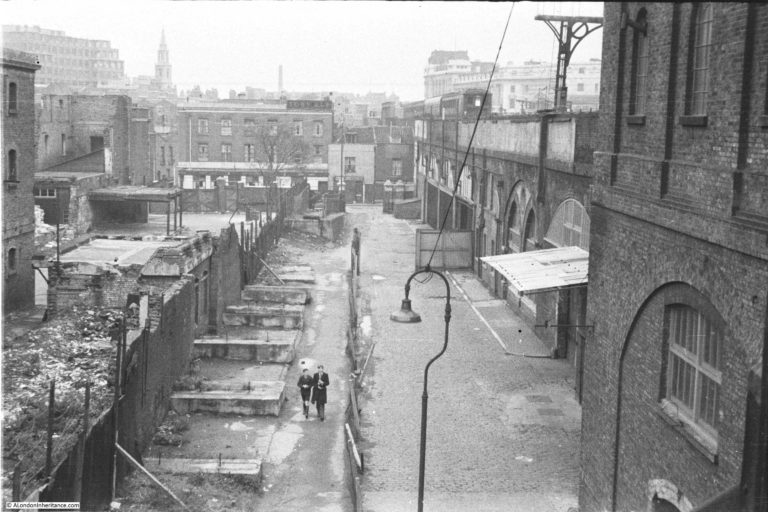

Bache’s Street is a short street of about 106 metres / 348 feet. Nearly every building dates from the later half of the 20th century, and there is nothing of any real architectural merit. It is the sort of street you would only visit if you had business there, or it was on the route to somewhere else.

The view along Bache’s Street, looking north from Brunswick Place.

I believe that if you dig deep enough, there is always a story to tell about any street in London, and my approach to Bache’s Street is based on a visit to Chepstow in South Wales last year.

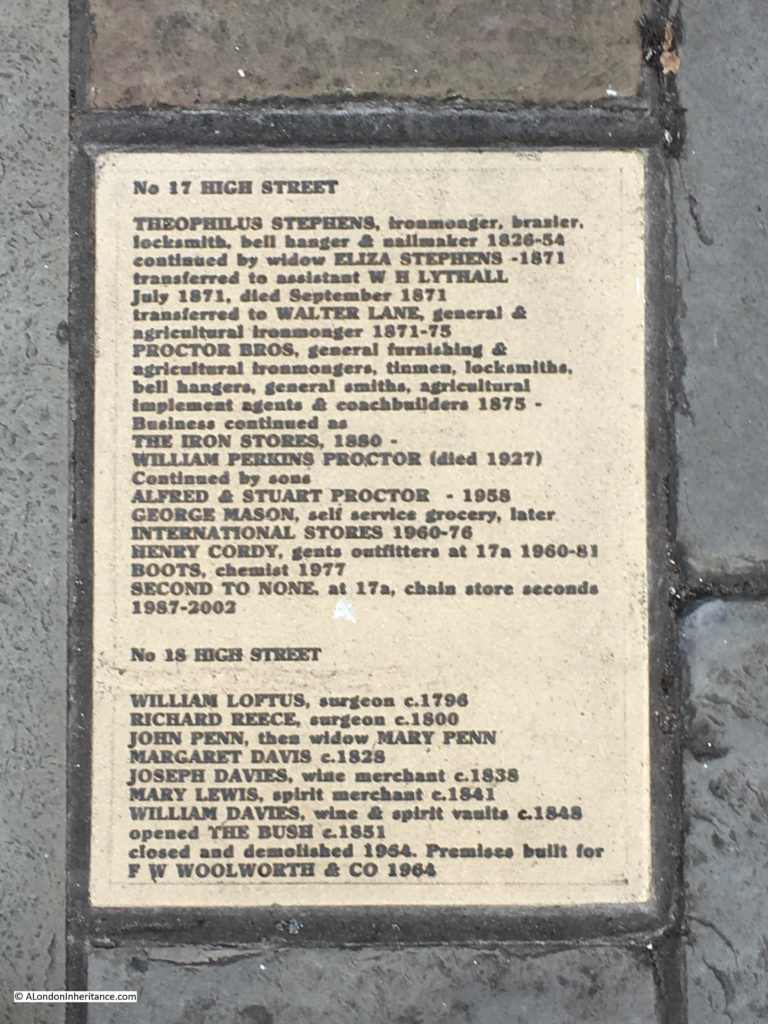

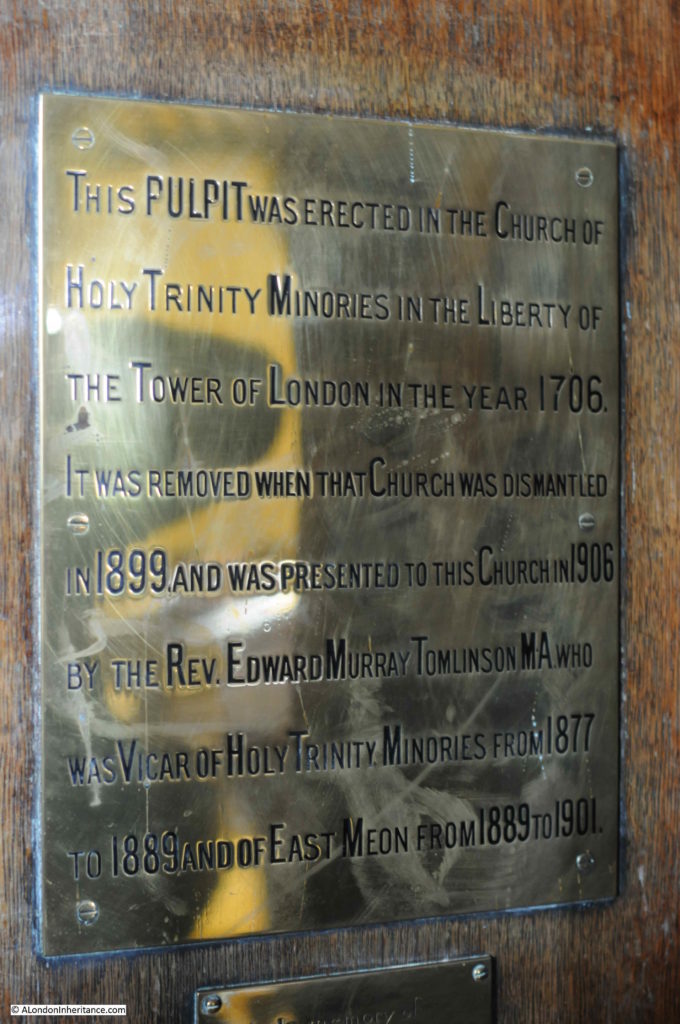

Chepstow have implemented a brilliant scheme to highlight who has lived in buildings, along with the business carried out, along the high street of the town. Plaques in the pavement, in front of each building list the previous residents and trades that occupied the building.

Close-up of the plaque for numbers 17 and 18 Chepstow High Street.

I think this is a brilliant idea. It makes the history of a place very tangible at the individual level, and standing in front of a building, you can imagine all those who have lived and worked there before.

How could I apply this approach to Bache’s Street? Using census data, could I develop a similar virtual approach, and what else could this data tell us about a typical street in north London?

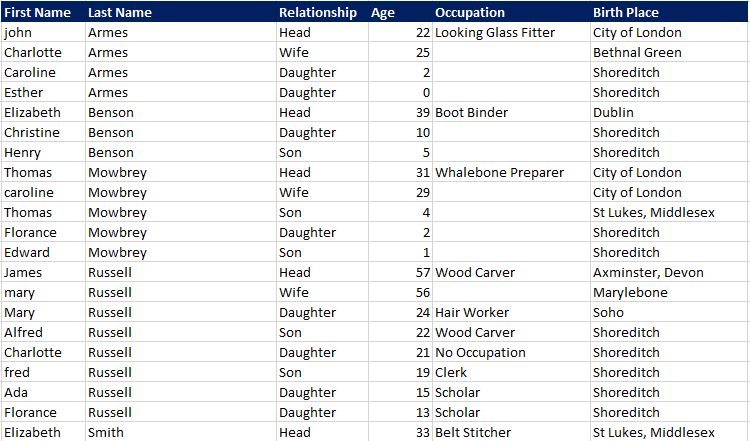

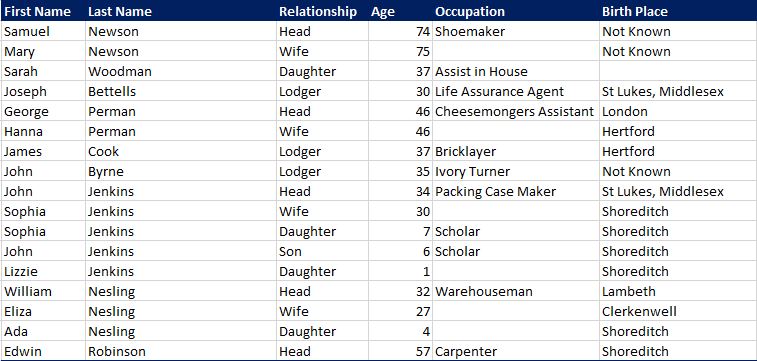

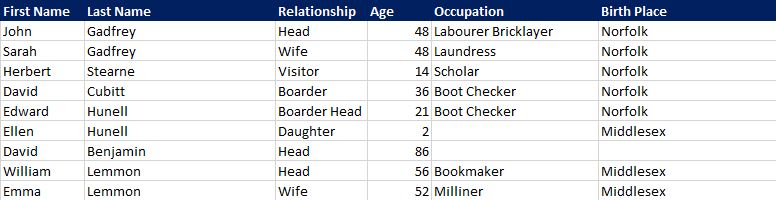

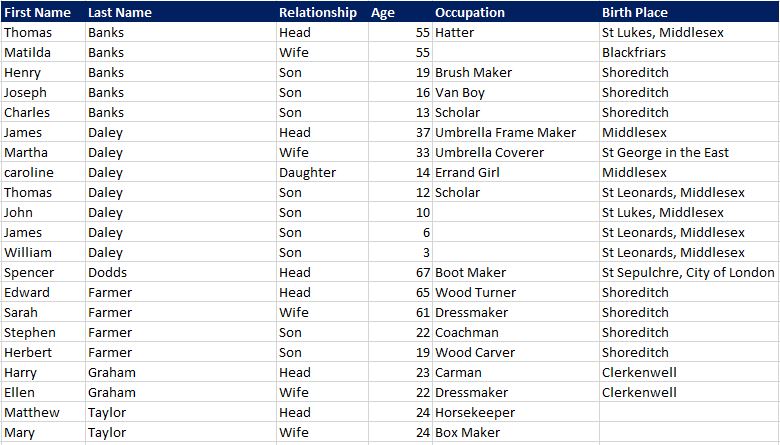

Using census data from 1881, I built a spreadsheet so the data could be manipulated and sorted. I only had time to work on the 1881 census, but following through on other census years provides a view of how streets and people change over time – I hope to cover this in a future post.

Later in this post, I will take you on a virtual walk through Bache’s Street to meet all 329 people resident in the street for the 1881 census. The data also provides us with a view of how people lived at the time and where they were from, so I will explore this as well, but before getting into this level of detail, some background to the street.

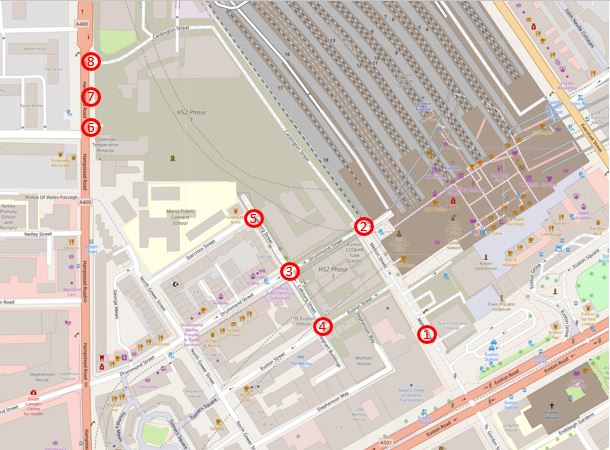

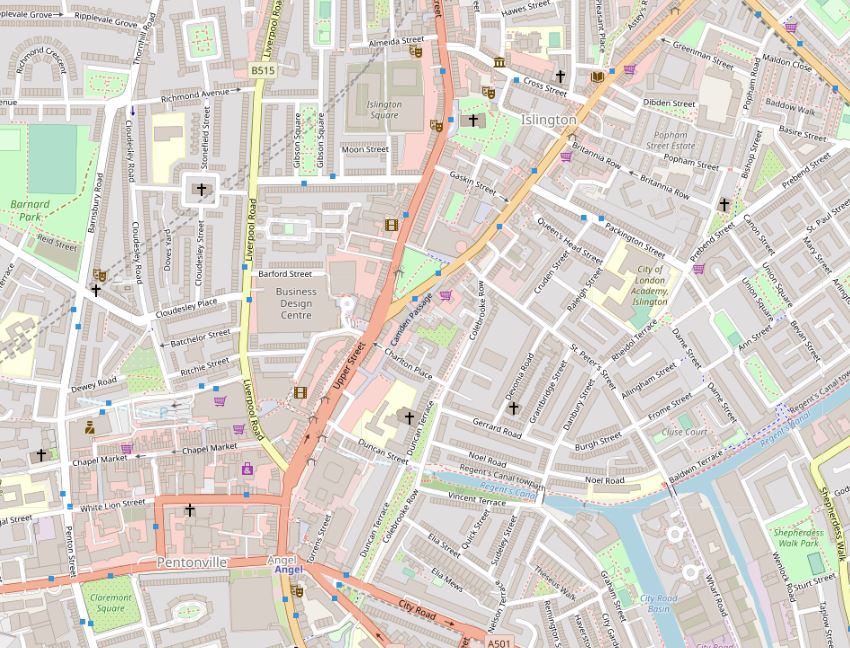

The following map extract shows the location of Bache’s Street, a short distance north-east of the Old Street roundabout (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

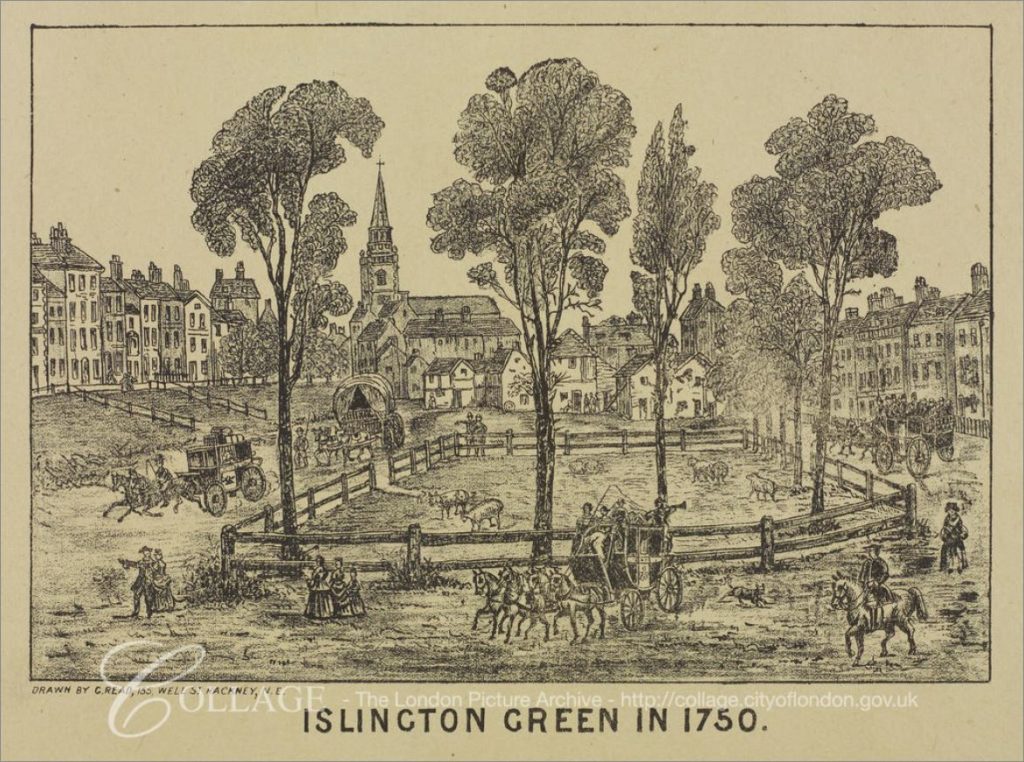

The street did not exist in 1746. The area consisted of fields, formal gardens and orchards. The Haberdashers Hospital was to the east, and the newly built Charles Square was to the south-east. The following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows the area, with the future location of Bache’s Street marked with a red line.

By 1828, the fields had been built over as London’s northward expansion gathered pace. Greenwood’s map of 1828 shows a street in the position of Bache’s Street, but with the name Charles Street. Buildings are shown on either side of the street, and the length of buildings on the eastern side of the street are named Bache’s Row.

I suspect that Bache’s Row may provide a source for the name. The form of the name implies it could have been named after the landowner, builder or owner of the row of houses along the eastern side of the street.

Reynolds’s New Map of London dated 1847 still has the street labelled as Charles Street. The street is circled in the following map extract which also shows how the area had changed in the 100 years since Rocque’s map.

By the 1881 census, the street name had changed from Charles Street to Bache’s Street – for some reason, the name of the row of houses on the east side had been used for the whole street.

The 1894 revision of the Ordnance Survey map shows a street with houses lining the majority of both sides, but with a Glass Manufactory on the south-east corner of the street, replacing some of the houses.

The Charles Booth poverty map for the area is shown below:

Bache’s Street is in the centre of the map, and the colour code used for the households along the street is defined as “Mixed, some comfortable, others poor”.

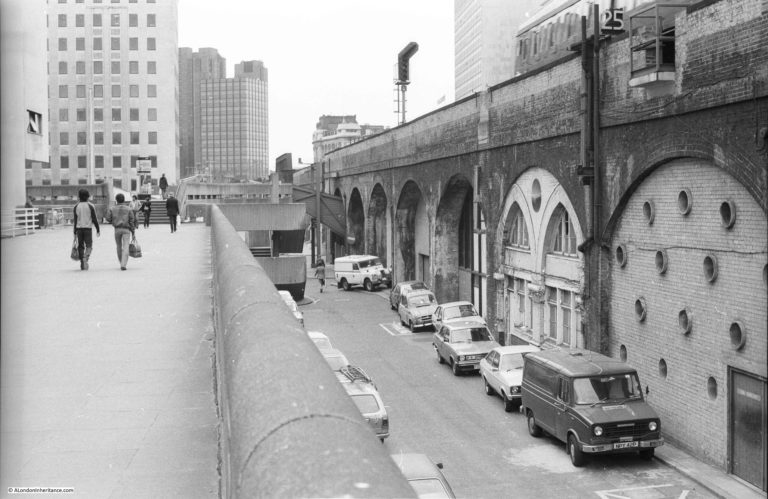

Bache’s Street was explored by George H. Duckworth for Booth’s survey and he walked the area on the 17th May 1898 with Police Constable W.R. Ryland, and he wrote “Only a few dwelling houses at the north east and south east end left. The rest have been replaced by large factories.” This was the start of the change of the street from residential to commercial.

There are also newspaper reports that report on the poor conditions of some of the houses along the street with Aristocratic landlords (Lord Arlington) charging rents for a well maintained property, but which the Medical Officer of Health had found to be unfit for human occupation.

The 1945 maps used for the LCC Bomb Damage maps still show the street much as it was in 1894. Most of the street survived the war, however there was damage to two building half way along the eastern side of the street.

The remaining houses that originally lined Bache’s Street would disappear in the decades following the war, with the land being used for offices and business purposes – a process which has reversed slightly with some of the buildings being converted to flats.

So what can we learn about Bache’s Street from the 1881 census, and more generally about what life was like in the area north of Old Street in the late 19th century?

I transferred the census data for the 329 people living in Bache’s Street at the time of the 1881 census into a spreadsheet, and this is what I found.

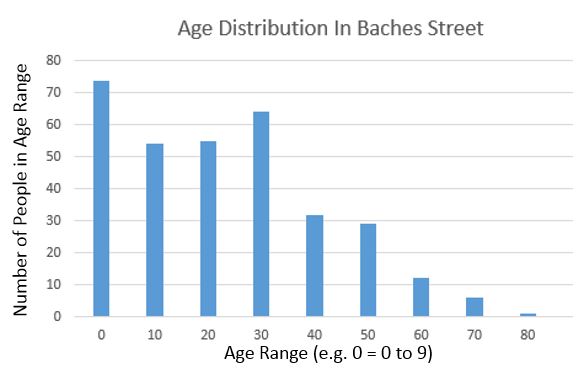

The occupants of Bache’s Street were young. The following graph shows the age distribution of the residents.

The majority of residents were under the age of 40, and the highest number of residents were in the age range 0 to 9.

From the age of 40 onward, there was a rapid decrease in the number of people, with only one resident older than 80.

This could be explained by the type of people attracted to the street – younger families, or it could illustrate the life expectancy of those living in the area in the late 19th century.

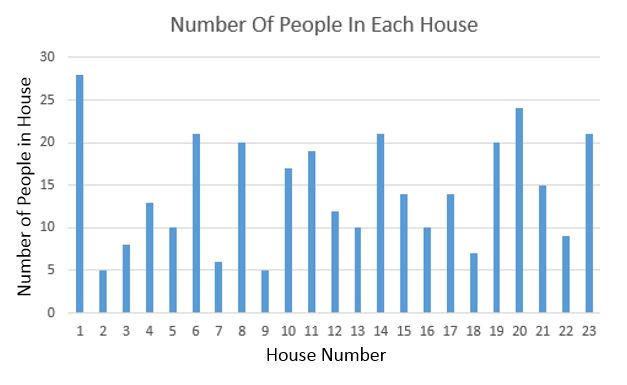

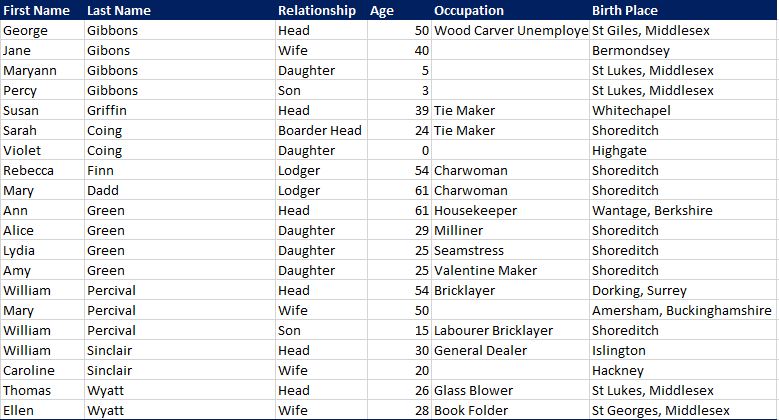

The residents of Bache’s Street were generally poor manual workers. There were only 23 houses in the street, but 329 residents. The following graph shows the number of residents at each house in the street. showing how densely packed they were into this short street.

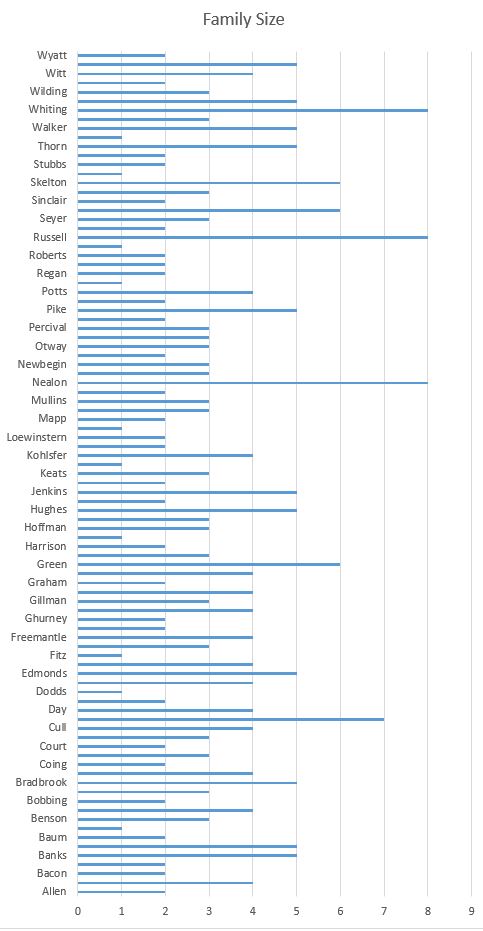

These houses were occupied by multiple families, and families were not that large. The following bar chart shows the number of members of each family living in Bache’s Street in 1881 (every other name has been omitted to make the vertical axis readable, all families are included. I have only included family members and have excluded lodgers and visitors).

The largest families in the street consisted of 8 people. The average number of family members across the street was 3.15, so in many ways not that different to today. The families with a single member are typically widows or widowers.

The majority of people living in Bache’s Street in 1881 were born in London, but a significant percentage had moved to London from the rest of the country, and from abroad.

This included 9 people from Germany, 1 from Australia, 1 from Ireland, 1 from Jersey, 1 from Switzerland and 1 from Australia.

I have plotted the birth towns of Bache’s Street residents from the rest of the country in the following map:

People moved from major industrial towns such as Manchester and Birmingham as well as market town’s such as Bridport in Dorset.

Not a single resident was listed in the census as being born in Scotland or Wales.

What is interesting is the north / south of the river split. There has always been a very distinctive split across London just by travelling across the River Thames. For those living in Bache’s Street, and being born in London, the vast majority were from north of the river. Of the 329 people in the street in 1881, only 11 people were identified as being born south of the river (Bermondsey 2, Lambeth 4, Lewisham 1, Greenwich 1, Southwark 1, Kennington 1, Newington 1).

There were more people in Bache’s Street from outside the UK in 1881, than from South London. It would be an interesting study to see if this was typical and whether there was very little migration or marriage between south and north London, and how far that has changed.

An extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey map is shown below with Bache’s Street in the centre of the map.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

There were 23 individual house numbers in the 1881 census and I have tried to align these accurately on the 1894 Ordnance Survey map, so when we take a virtual walk through the street, we can see where the families lived.

The Public House (P.H.) at the top right of the street was the Globe and had an address on Great Chart Street.

The building on the top left also I suspect had an address on Great Chart Street, and the building below this may have had an address on Styman Street as the longer edge was on this street.

The Glass Manufactory at lower right had been built between the 1881 census and the 1894 map, so working down from the top of the street, I assume that house numbers 2, 4 and 6 occupied this space,

So, lets take a virtual walk along Bache’s Street to meet the residents of the street in 1881.

Today, all the houses have disappeared. The “wework” office block shown in the following photo occupies the space of the odd numbered houses from 1 to 15.

Number 1 Bache’s Street

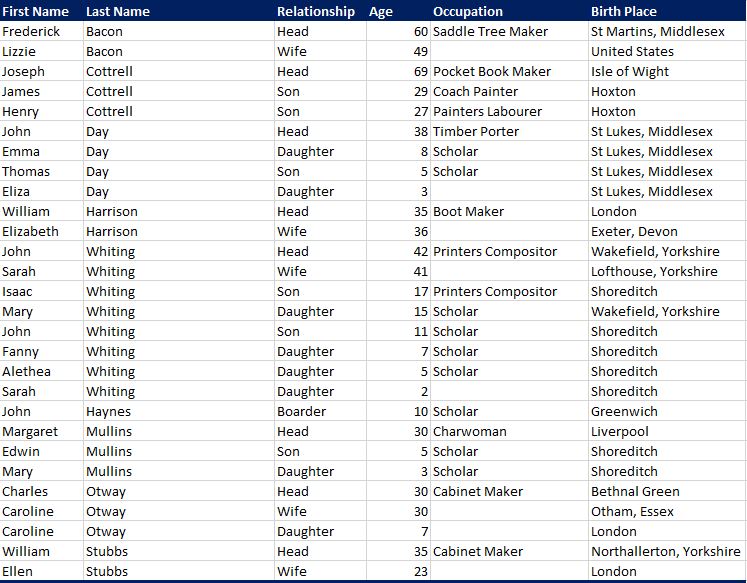

Number 1 Bache’s Street had the most people of any individual house on the street, and also included one of the largest families (the Whiting’s).

Lizzie Bacon is listed as being born in the United States, it would be interesting to know why she moved to London, and how she met her husband Frederick.

The children of many of the residents often had a job related to their parent, for example John Whiting was a Printers Compositor as was his 17 year old son.

Directly across the street from number 1, was the Glass Manufactory in the 1894 OS map. Today, the same space is occupied by an office block. In 1881, this was houses 2,4 and 6.

Number 2 and 3 Bache’s Street

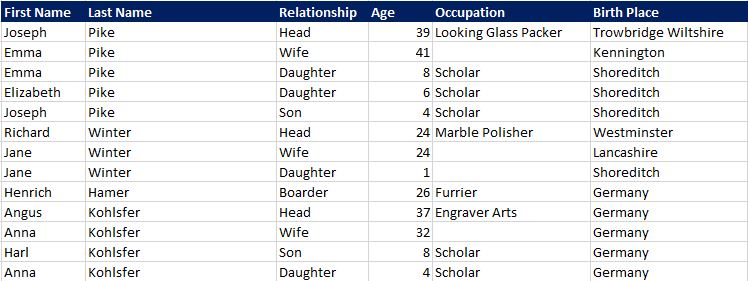

i have combined these two houses, opposite each other on the southern end of the street, as they had a smaller number of people. The Pike family were the only residents of number 2, with the Winter and Kohlsfer families in number 3.

Number 3 had a German family, the Kohlsfer. They were obviously recent immigrants to London as their youngest daughter aged 4 had been born in Germany.

There were a number of lodgers throughout the street and lodgers often would come from the same home village or town as the main family, demonstrating the contacts between immigrants to London and their place of birth persisted. The Kohlsfer’s had a German born lodger or boarder, Henrich Hamer who was a 26 year old Furrier from Germany.

Number 4 Bache’s Street

Number 4 has a possibly interesting tale. Charles Newbegin is listed as a Master Mariner. His wife Elizabeth was born in Jersey in the Channel Islands. Did they meet after he had sailed to Jersey, and he brought her back to London?

The list of occupations also shows how specific jobs were at the time. Many tasks which would be automated in the future were still manual, so for example in number 4 you will find an Envelope Folder.

Number 5 Bache’s Street

It is interesting to speculate on how people moved around at the time.

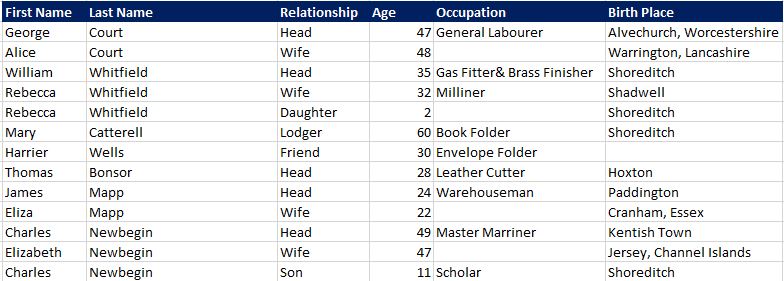

Take the Cull family at number 5. Elizabeth Cull, the head of the family (she is not listed as a widow, but is living with her children as a single parent) was born in London, as was her oldest daughter and her son. The middle child, aged 10 was listed as being born in Kendal, Westmoreland.

In the 1871 census, Elizabeth Cull is recorded as living in Kendal with her husband Joseph Cull who was originally from Ireland. So had they moved to London where Clara was born, then moved back to Kendal when Kate was born, and back to London for Joseph’s birth (named after his father). There is no record of what happened to the husband / father Joseph Cull – did he return to Ireland?

Number 6 Bache’s Street

Many of the families in Bache’s Street continued to have older children at home. For example in number 6, the Russel family still had children aged 24, 22, 21 and 19 at home. If children were not married, this was probably an economical way for the family to live with the Russell family having a total of 4 members working. It must though have contributed to very crowded conditions and as there were 4 families and the single Elizabeth Smith living in number 6, the Russell family could not have had more than a couple of rooms.

Number 7 Bache’s Street

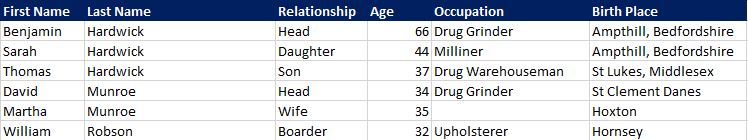

There are so many interesting job descriptions in the census and in number 7 there were two “Drug Grinders”.

Number 8 Bache’s Street

Lydia Green who is listed in the census as living at number 8 would suffer a tragic fate in the house six years after the census. The following is a report from the London Daily News on the 11th February 1887:

“The victim Lydia Green, an unmarried woman, thirty-one years of age, was found dead in her bedroom last Saturday morning. She was nearly dressed, she lay on her back in a pool of blood, and she bore a terrible wound on the head, as well as other wounds on the hand and jaw. She lived with her mother and a widowed sister at Baches-street, Hoxton, and she and the sister slept in a back room on the ground floor.

Both sisters went out to work, but Alice, the widowed one, usually rose first, and left the house at ten minutes to seven. The deceased woman rose a little later, and at about half-past seven she usually knocked on the ceiling, as a signal to her mother, who slept in the room above.

On Friday last she went to bed in perfectly good health, her mother previously having heard her talking at the street door with Thomas Currell, a young man with whom she had ‘kept company’ for some years. On Saturday morning, just after the widowed sister had left for her work, the mother in her bedroom, heard noises, as of a person falling, in the room below. She heard these noises three separate time, and after them the step of someone walking sharply along the passage and, the slamming of the street-door. The noises do not appear to have alarmed her, and she lay in bed until half-past seven, when she expected to hear her daughter’s signal on the ceiling.

No signal came, and then the mother went downstairs, and found the poor woman dead as described. There were two wounds on the right hand, which seemed to have been inflicted by bullets, though no bullets were found in them, two other wounds on the right jaw, in which were found some piece of metal that might have been parts of bullets, and a wound above the right eye which extended to the brain.”

The article goes on to explain that Thomas Currell had been out of work since the previous August and may have been jealous of Lydia. Currell was known to Scotland Yard and had been twice in trouble before. They were engaged, however a couple of weeks prior to her death, Lydia had wanted to break off the engagement

At the time of the report Thomas Currell had disappeared, however he would hand himself in to the police a few days later, having no money and suffering from cold and starvation. Newspaper reports at the time complained about the failure of the police to find Currell and it was only because he handed himself in that he was caught. If he had more money, he would have escaped London.

He appeared at the Old Bailey during the first week of April 1887, found guilty and sentenced to death. He was hung at Newgate on the 18th April 1887 at the age of 31.

Number 9 Bache’s Street

Number 9 Bache’s Street only had a single family. If I have my mapping of house numbers to houses on the Ordnance Survey map correct, then number 6 was the same size house as the rest along this side of the street, so no idea why there was only a single family.

Perhaps they were affluent enough to cover the costs of the whole house, or perhaps this was a temporary position, as people in other rooms had moved on, and no one else had yet moved into the house. The census provides a snapshot of a specific point in time.

Moving back to the even side of the street, and the building in the following photo occupies the space where numbers 8, 10 and 12 were in the 1894 Ordnance Survey map.

Number 10 Bache’s Street

Number 10 again shows a range of professions, and also how families must have retained contact with their home towns.

Hanna Perman is listed as being born in Hertford, and the family have a lodger, James Cook, a bricklayer who also came from Hertford. Perman was Hanna’s married name, so John Cook could have been a relative.

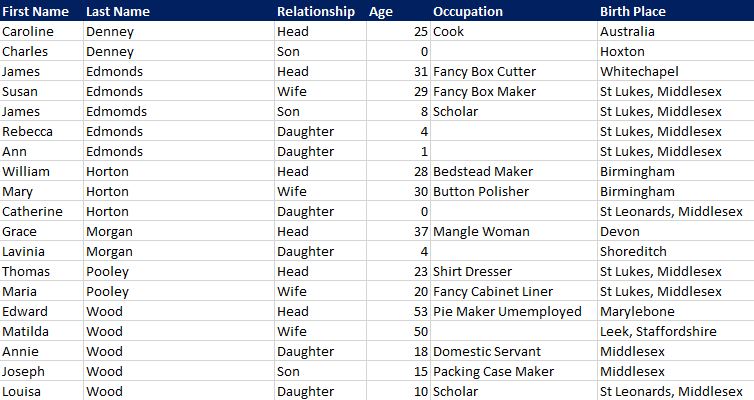

Number 11 Bache’s Street

Residents of number 11 show how families worked together, probably working at home. James Edmonds was a Fancy Box Cutter and his wide Susan was a Fancy Box Maker.

Caroline Denney is listed as being from Australia. She is 25, has a newborn son, and there is no other member of her household. It does make you wonder how she came to be living as a single parent in a Hoxton Street, a long way from her birth place in Australia.

Many of the Occupation entries are blank, implying that the person was not employed. Occasionally there is a reference to being unemployed, or out of work, along with their profession. An example in number 11 is Edward Wood, an unemployed pie maker.

Number 12 Bache’s Street

An average number of residents, but still with 4 families living together.

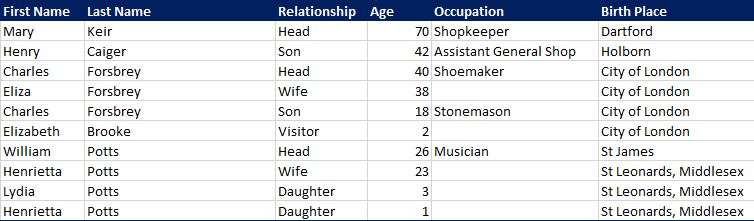

Number 13 Bache’s Street

By far the majority of occupations are manual work, but occasionally there is something different, such as William Potts being listed as a Musician, but no indication of what instrument or where he played.

The building in the following photo occupies the space where 14 to 22 were located in the 1894 map:

Number 14 Bache’s Street

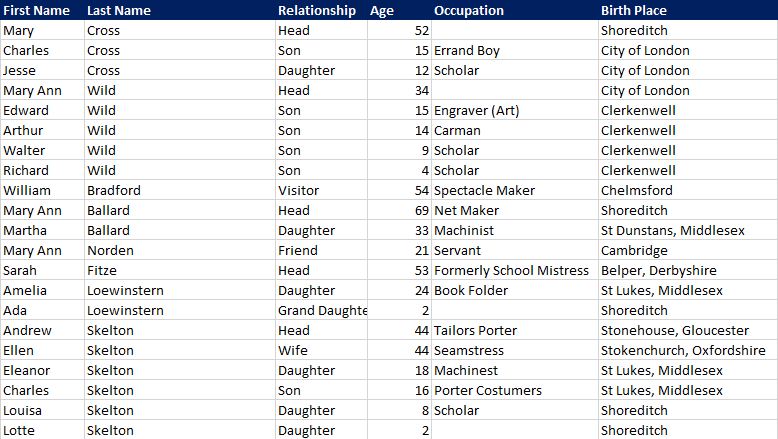

By the age of 15, most children were expected to be working, very few are listed as still being a Scholar from 15 onward.

In number 14, 15 year old Charles Cross was an Errand Boy, Edward Wild was an Engraver and Arthur Wild, a year younger at 14, was a Carman.

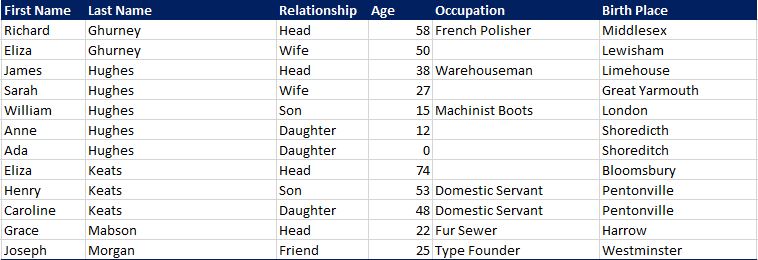

Number 15 Bache’s Street

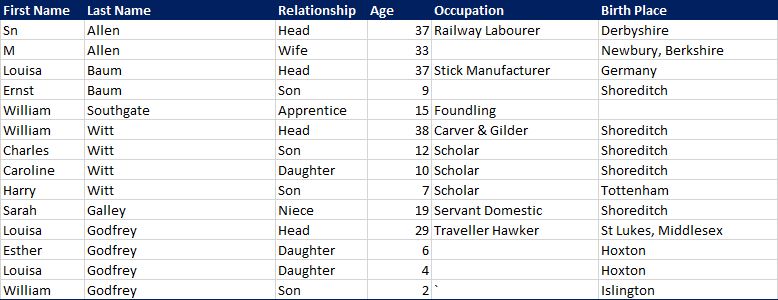

Louisa Baum was a German born Stick Manufacturer and appears to have been a single parent of a 9 year old son, although I will caveat that with the census being a snapshot in time, so her husband may have been away working or travelling. Census data can only can only tell us so much.

Number 16 Bache’s Street

Whilst the majority of residents were born in the London area, a significant number were from the rest of the country, and from abroad. In number 16, Thomas Bobbing from Shoreditch had married Lizzie from Switzerland. Did they meet in London or Switzerland?

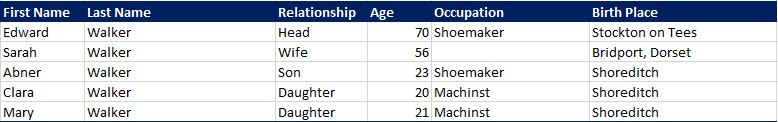

The following photo shows the space once occupied by numbers 17, 19, 21 and 23:

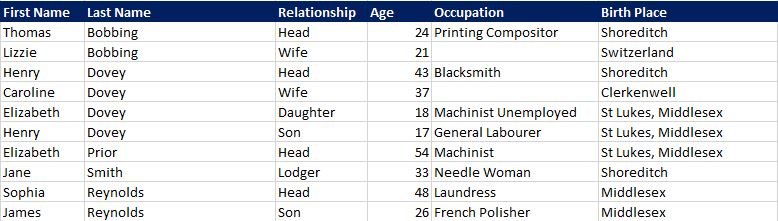

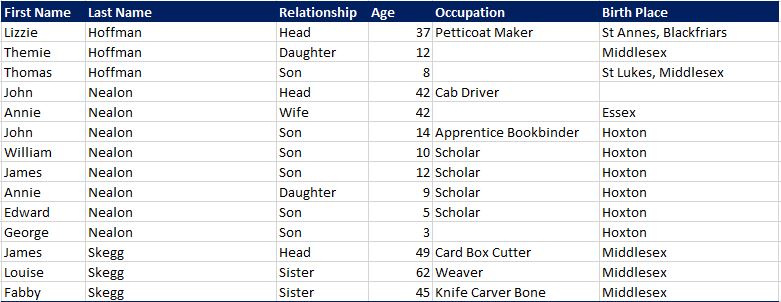

Number 17 Bache’s Street

Number 17 had one of the larger family’s with the Nealon’s having 6 children. John Nealon would have been supporting them all through his job as a Cab Driver, and although their eldest son was an Apprentice Bookbinder at age 14, I doubt he was earning very much.

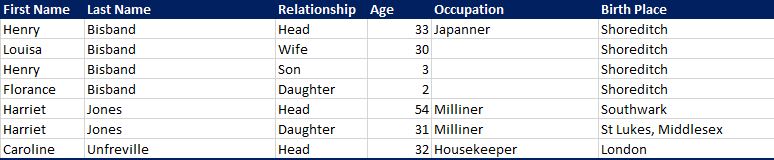

Number 18 Bache’s Street

In number 18, Henry Bisband’s occupation is listed as “Japanner”. This was a specialist way of applying a varnish or lacquer, and was intended to imitate Asian furniture and small metalwork.

Number 19 Bache’s Street

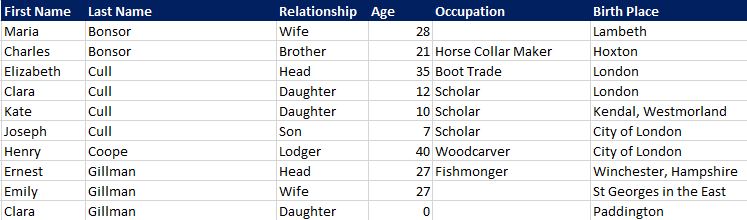

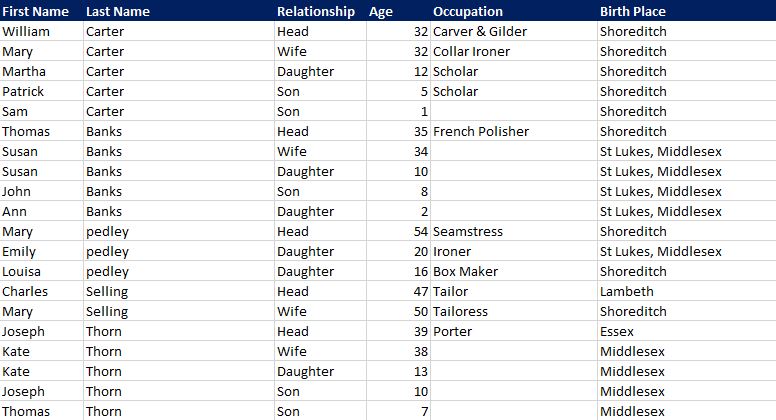

Number 19 was one of the most populated houses on the street with five families and 20 people. The house was also one of the few with someone from south of the river as Charles Selling was born in Lambeth. Apart from Joseph Thorn from Essex, everyone else in number 19 was local.

Number 20 Bache’s Street

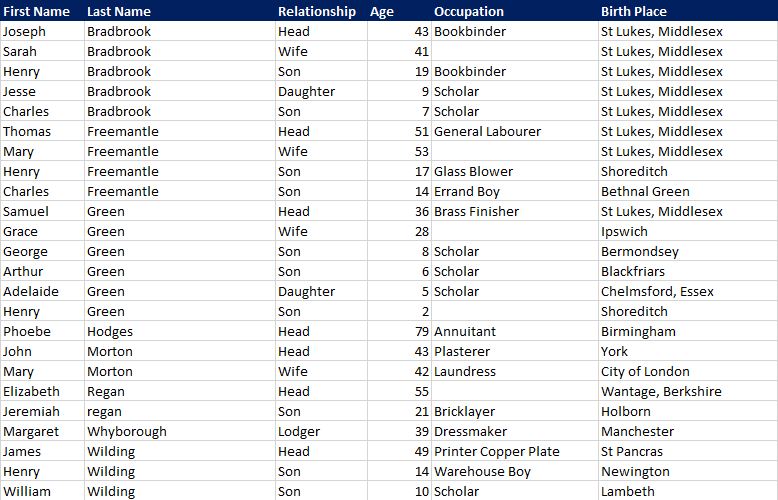

Number 20 had more people than number 19 with 24 people across 7 families, although one family had a single member. The census still listed Phoebe Hodges as the “Head” although she appears to be the only family member.

Phoebe’s occupation is listed as Annuitant, someone who receives an annuity. There is no clue as to her previous circumstances, or profession so no indication as to why she was the only person on the street listed as receiving an annuity. I suspect that this was somewhat unusual on streets such as Bache’s Street, but at 79, and apparently on her own, she would have needed such an income to survive.

Most houses on the street had a single parent, probably indicative of the mortality rate at the time. In number 20 as well as Phoebe, James Wilding is listed as a widower.

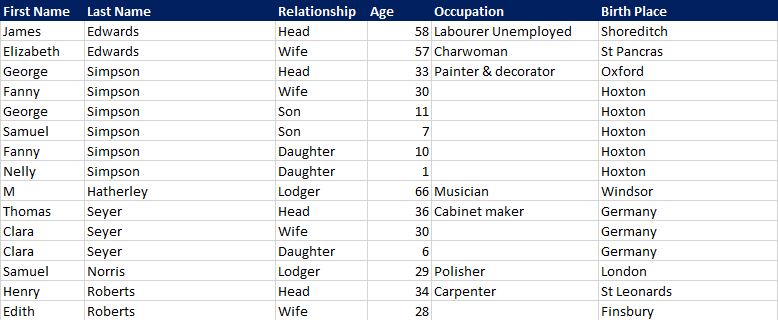

Number 21 Bache’s Street

James Edwards in number 21 is listed as an Unemployed Labourer. He was 58, and therefore one of the older residents on the street. Late 19th century diet, healthcare and a life of manual work probably meant that by today’s standards he would have appeared much older than 58, and he could have been unemployed due to health conditions. I would not really have wanted to have been a labourer at the age of 58 in Victorian London. James and his wife Elizabeth would have had to support themselves on Elizabeth’s money as a Charwoman.

Number 21 also had another German family, with the Seyer’s who again must have moved to London relatively recently as their daughter Clara aged 6 was also born in Germany.

Number 21 also illustrates how frequently older, or only children were named after their parents. George Simpson had the same name as his father, Fanny Simpson had the same name as her mother, and Clara Seyer also had the same name as her mother.

Number 22 Bache’s Street

Number 22 had the oldest resident on the street with David Benjamin at the impressive age of 86. He was one of the few who were born in the 18th century. He is listed as “Head” so must have been on his own (if he lived with his children, then he would have been head and his children, whatever their age, would have been listed as children).

He does not have an occupation, so one wonders how he supported himself.

Number 23 Bache’s Street

And finally to the last house on the street, number 23. Again, a large number of people in the house with a wide range of occupations.

James and Martha Daley must have worked together as an Umbrella Frame Maker and Umbrella Coverer – again very specific job roles. The four members of the Farmer family consisted of a Wood Turner, Dressmaker, Coachman and a Wood Carver.

Spencer Dodds at the age of 67 still had to work as a Boot Maker.

Number 23 was the last numbered house on the street. At the northern end of Bache’s Street were two large buildings on the 1894 map, but both of these had Chart Street addresses as they do today.

On the north-east corner of the street was a pub in 1894. This was the Globe. The pub closed in 2013 (although a later version of the building than the one on the 1894 map), and the old pub was finally demolished in 2018 to be replaced with the typical London early 21st century brick clad apartment building shown in the following photo.

Directly opposite, on the north-west corner of Bache’s Street is this building, again with an address in Chart Street.

So that was Bache’s Street in 1881. If you accidentally walked through the street (unless you live or work there), I suspect you would not give the street a second glance, and hurry on to your destination, however scratch the surface and we can really understand what life was like on the street, 140 years ago.

Was this an ordinary London street? Probably, a typical working class street where families would cluster together in a limited number of rooms with other families in the same house, all working manual jobs, and struggling to make enough money to survive in any degree of comfort.

Bache’s Street also had a significant number of residents from outside of London and abroad. London has always been a city of inward migration.

Bache’s Street would become more industrial in the decades to come. The Glass Manufactory built over houses 2, 4 and 6 was the first sign of this change.

I may try to return to Bache’s Street in the future and follow-up on later census data to track how the street changed, and what happened to those resident in 1881.

Now I wonder if I can get the above carved into paving stones and placed along the street?