The church of St Dunstan in the West can be found in Fleet Street on the edge of the City. The current church is not that old having been built between 1830 and 1833, however a church has been here for many centuries.

The original church was dismantled as part of the widening of Fleet Street and the land available for the replacement church was slightly further back and with limited space available, the design and layout of the church is somewhat unusual.

Walking up Fleet Street and heading towards the Strand, the tower of St Dunstan in the West still stands clear of the surrounding buildings.

Indeed not that much has changed in the past 100 years:

The first mention of a church on the site was around the year 1170 and the core of the medieval church survived the Great Fire and was demolished as part of the widening of Fleet Street when the new church was built further back as a replacement.

The church was built by John Shaw between the years 1830 and 1832. John Shaw senior died in 1832 and his son, also a John, completed the church. Various books claim that the tower and octagonal lantern were modelled on either St Botolph’s in Boston or All Souls Pavement in York – both are similar and we will probably never know which was the real inspiration.

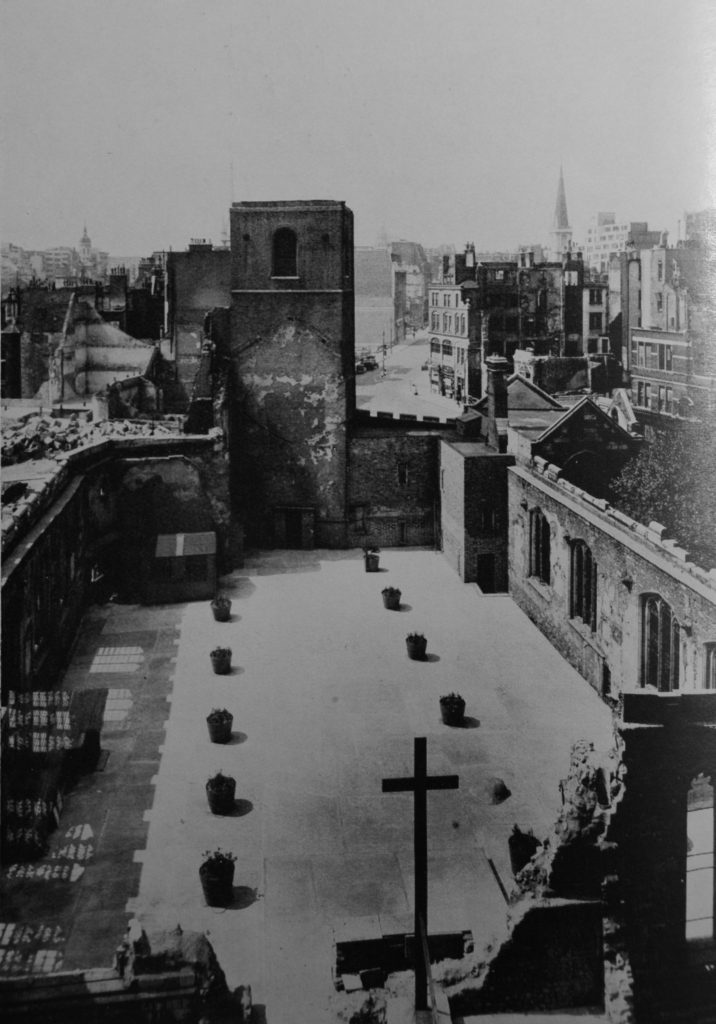

The church was damaged during the last war, but was fully restored in 1950.

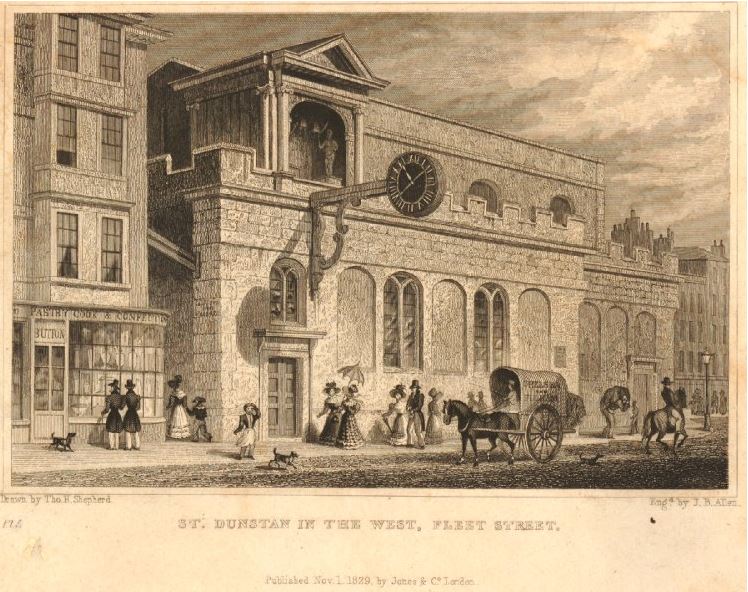

Just to the right of the tower is the clock which was made by Thomas Harris in 1671 for the original church. It was saved by Lord Hertford in 1828 just before the original church was demolished, who then installed it on his villa in Regent’s Park. It was returned to the church in 1935. In a recess behind the clock are two figures either side of a pair of bells.

To the right of the clock, further back from the road is the oldest statue of Queen Elizabeth I. Made probably around 1586 and therefore during the reign of Elizabeth I, the statue was originally on the Ludgate, one of the gated entrances to the City. The plaque below the statue reads:

“This statue of Queen Elizabeth formerly stood on the West side of LUDGATE. That gate being taken down in 1760 to open the Street, was given by the City to Sir Francis Gosling, Alderman of this Ward who caused it to be placed here”.

Outside the front of the church is also the Northcliffe Memorial from 1930, who arranged the return of the clock.

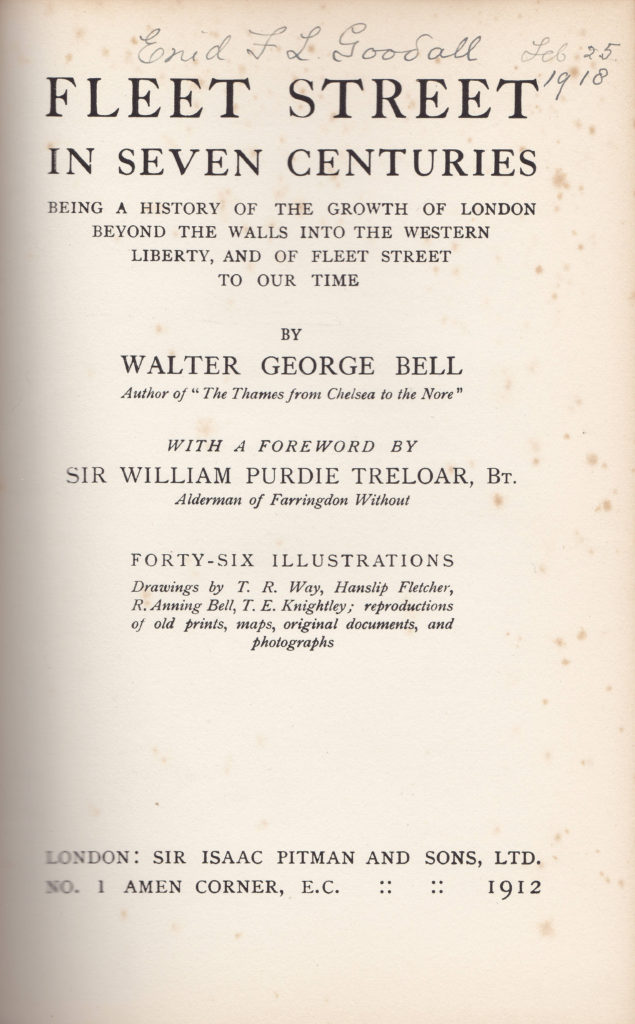

The Book “Fleet Street in Seven Centuries”, by Walter G. Bell. published in 1912 provides an insight into how St. Dunstan’s in the West featured in the life of the city, along with the types of incidents that troubled the lives of those who lived in the area.

The earliest example is from the early years of the reign of Richard II (1377 – 1399) and tells the story of one William Hughlot who, within Temple Bar, in the parish of St Dunstan’s West, Fletestrete entered a shop owned by John Elyngham, a barber and by force of arms, William Hughlot drew his dagger and wounded, beat and maltreated the luckless barber.

Whilst this attack was taking place, the barber’s wife made a great outcry which attracted the attention of John Rote, Alderman who tried to stop the attack, however Hughlot then started to attack the Alderman who would have been killed had not the Alderman “manfully defended himself”.

John Wilman, a constable of Fletestrete seeing Hughnot trying to kill the Alderman arrested Hughnot but was also wounded in the process.

The attack on a city Alderman was classed as “a greater offence against the City’s dignity than would have been a massacre of princes”.

At trial, the judgement was that Hughlot should have his right hand, with which he first drew the dagger and afterwards drew his sword upon the Alderman cut off. This was described as the least punishment befitting such an offence. The sentence was about to be carried out, however the Alderman John Rote “in reverence for our lord the King and at the request of divers lords who entreated for the said William, begged of the Mayor and Alderman that execution of the judgement aforesaid might be remitted unto him”

After nine days of imprisonment Hughlot was released, but had to “carry from the Guildhall, through Chepe and Fletestrete, a lighted wax candle of three pounds weight to the Church of St. Dunstan, and there make offering of the same. And he was to find sureties for good behavior.”

In the 17th century, the church is described as having “gathered a little outlying colony of booksellers, who had their shops in the churchyard”,

During much of the 16th and 17th centuries the wardmote for the southside of the ward of Farringdon Without would meet at St Dunstan’s on St. Thomas’s Day when a grand jury and petty jury would consider local affairs. Example of the affairs brought to the wardmote were:

- Thomas Smythe, a waterman dwelling in Chancery Lane, resorted to the Temple Stairs and the Whitefriars Bridge to wash his clothes. For that he was presented to the Court of Alderman in 1559 as a common annoyer of all citizens.

- James Dalton suffered apprentices to play at dice and lose their master’s money and was also judged a common annoyer.

- In 1560, Hugh Barett, apprentice to Miles Fawcett, cloth worker was whipped, for that he had in a vile manner did hang a cord full of horns at the door of Henry Ewart, an officer of this City and the same on the Church door, the day the said officer was married.

- A Masterman kept a cellar under the house of Richard Blackman in Fleet Street, “wherein is much figytings, quarrelinge, and other great disorders to the great disquiet of his neighbours”.

- In 1603 there was presented Joan Spronoy, a woman given to slanderings, scoldings, and babbling, to the great disturbance of her neighbours and others

- In 1642, Widd Moody from Fleet Street was presented as she was found to keep a disorderly house, and for that in her widdhood she hath had as is credibly reported two children, and still doth do incontinently

Such was daily life in the area around St. Dunstan in the West.

The church of St Dunstan in the West escaped destruction during the Great Fire of London but was quickly put into good use when it was found to have escaped unharmed as it was soon stacked high with household contents from the houses that had been destroyed by the fire. The year preceding the Great Fire was not a good one in St. Dunstan as in 1665, out of 856 burials, 568 in only three months are marked “P” for Plague.

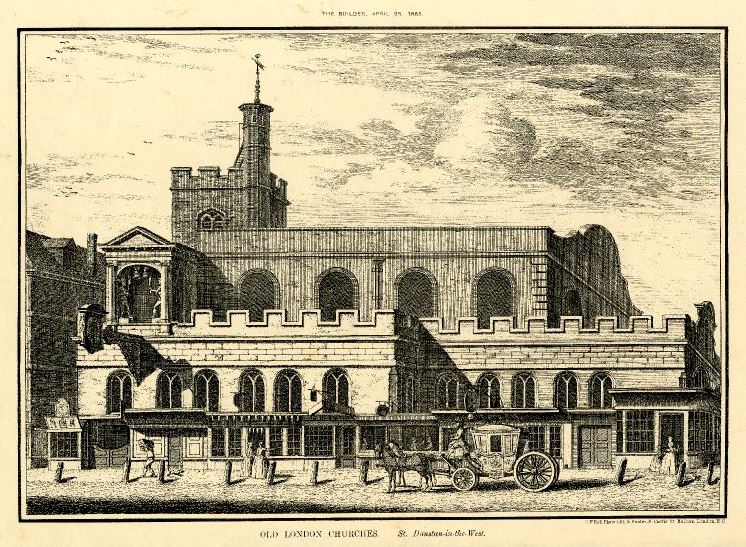

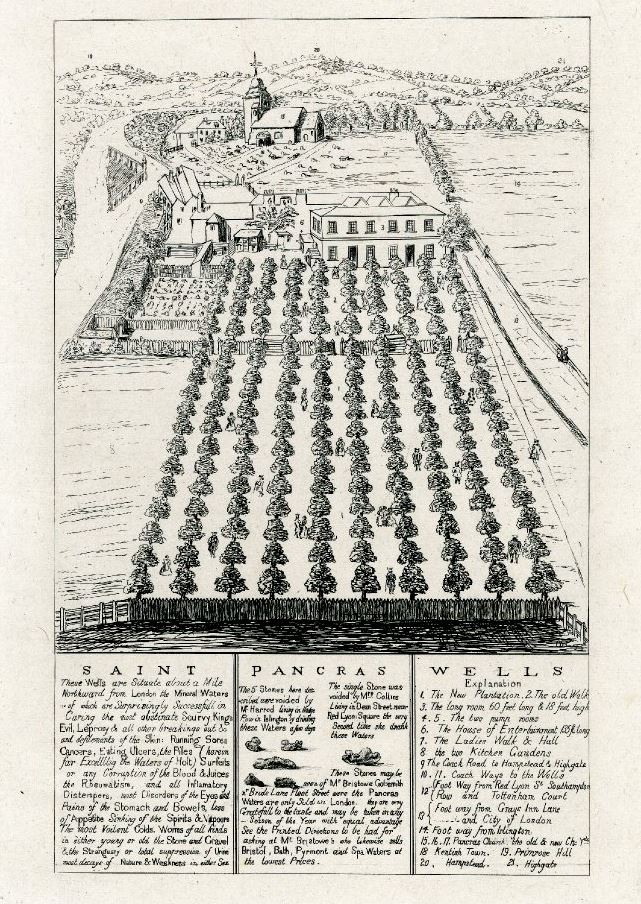

The following two prints show the original church. The only feature that was carried to the new design that we see now is the clock and the alcove above the clock with the two figures striking bells.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the area around St Dunstan was known for publishers and booksellers. Among these was John Smethwicke who had premises “under the diall” of St. Dunstan’s Church and who published “Hamlet” and “Romeo and Juliet”. Richard Marriot, a St. Dunstan’s bookseller published Isaak Walton’s “Complete Angler” and Matthias Walker was one of the publishers of John Milton’s “The Paradise Lost”.

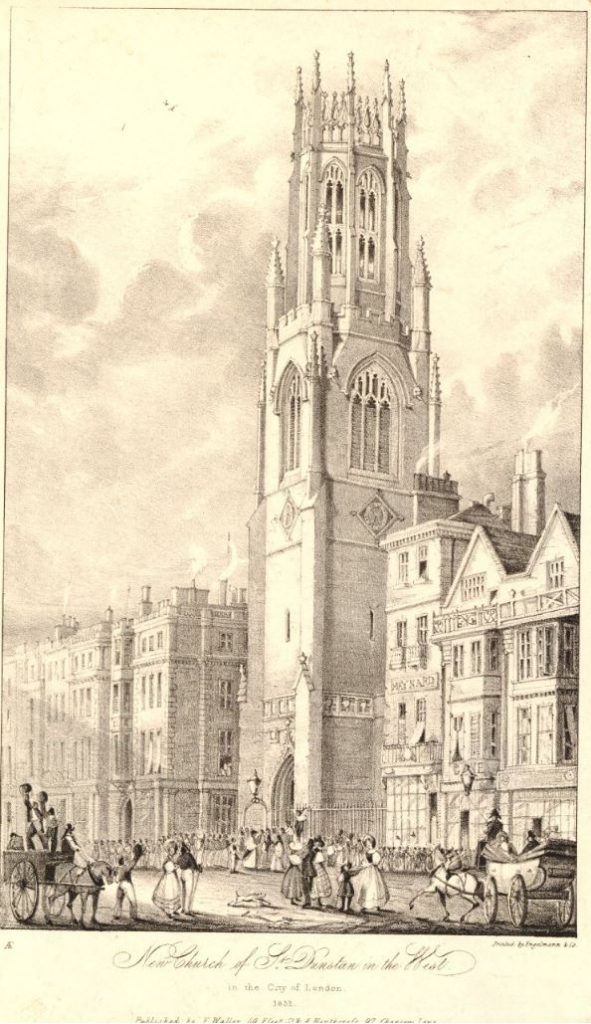

The following print from 1832 titled “New church of St Dunstan in the West” shows the new church when almost complete. There is a queue of people running to the left from the entrance to the church, possibly for the first opening of the new building.

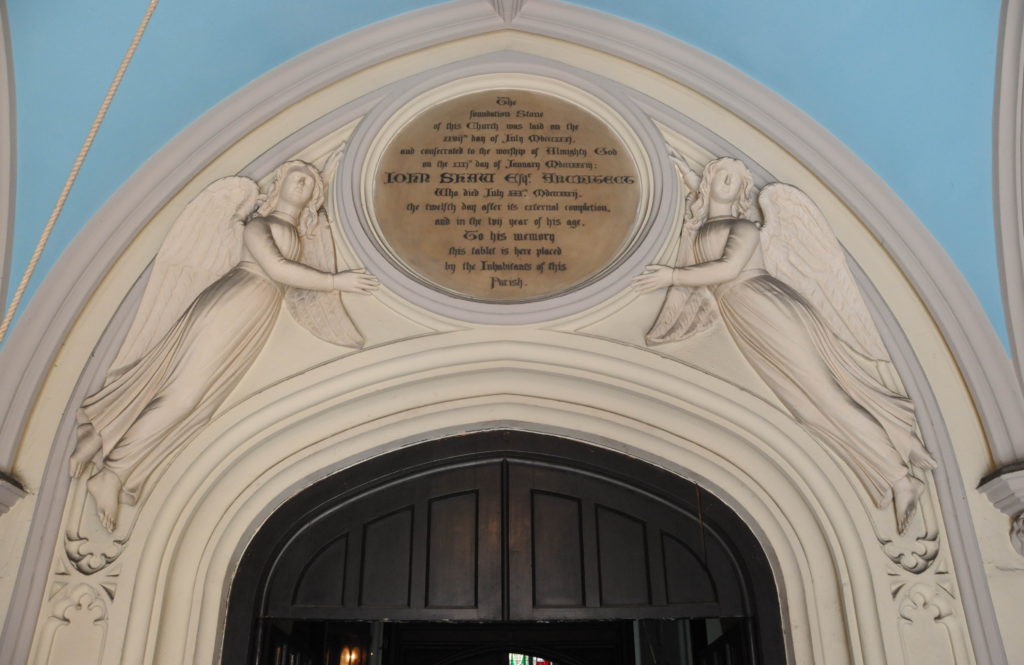

Time to leave Fleet Street and walk into the church. Immediately on entering the church is a plaque to the memory of the architect of the church, John Shaw. The plaque reads:

“The foundation stone of this Church was laid on the 27th day of July 1831 and consecrated to the worship of Almighty God on the 31st day of January 1833: John Shaw, Architect who died July 30th 1832, the 12th day after its external completion, and in the 57th year of his age. To his memory this tablet is here placed by the Inhabitants of this Parish.”

Once inside the church, the unusual layout can be seen. With the widening of Fleet Street, there was limited space to build a traditional style of church with a long nave, so an octagonal shape was used to maximise use of the space available and to provide alcoves around the edge of the church for uses such as individual chapels.

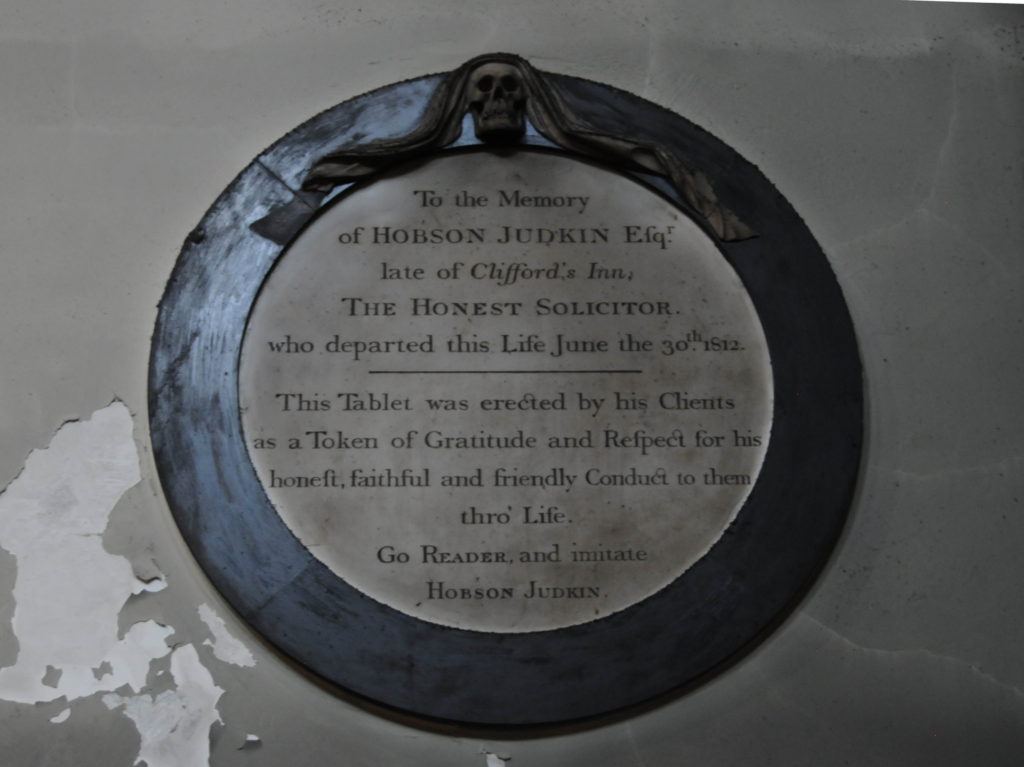

Along the walls of the church are a number of memorials and tablets including the following to Hobson Judkin – The Honest Solicitor.

Hobson Judkin was a solicitor at the nearby Clifford’s Inn and as well as recording his honesty, the tablet also probably tells us more about how other solicitors of the time were seen if it was significant to record the honesty of one individual. I found the last will and testament of Hobson Judkin in the National Archives, however it was written over two pages of very condensed script and to my untrained eye only the occasional words were legible. I will have to work on this more.

The closing sentence “Go reader and imitate Hobson Judkin” has to be one of the best epitaphs – who would not want to be remembered in this way?

Walter Thornbury writing in Old and New London mentions that in the record of the parish written by a Mr Noble, there is a remark on the extraordinary longevity attained by the incumbents of St. Dunstan. Dr. White held the living for 49 years, Dr. Grant for 59, the Rev. Joseph Williamson for 41 and the Rev. William Romaine for 46. Thornbury makes the telling remark that “the solution of the problem probably is that a good and secure income is the best promoter of longevity”. Then as ever, poverty does not result in a long life.

St Dunstan in the West is an Anglican Guild Church, and is also home to the Romanian Orthodox Church in London and has a superb altar screen that was brought to the church from a monastery in Bucharest in 1966.

The monument to Cuthbert Fetherston who died on the 10th December 1615, aged 78. Underneath is a plaque recording that his wife Katharine Fetherston was buried nearby in 1622 – “Who as they lived piously in wedlock more than forty years. So at their death desired to be intered together”.

The magnificent roof of the church, above eight identical windows.

The premises of the bank of C. Hoare and Co have been opposite the church since 1690 and the bank has had a long association with the church. Several members of the Hoare family are buried in the church, and the bank donated the stained glass windows behind the high altar.

The bank opposite still has the sign of “the golden bottle” hanging outside the entrance – a reminder of when buildings did not use numbers and some visible symbol was used to mark the location of specific people and businesses.

My visit to the church was on the day when the Friends of City Churches host visitors and I am grateful to the very knowledgeable team who provided considerable information on the history of the church.

I also used a number of books to research the history of St. Dunstan in the West, including the excellent Fleet Street in Seven Centuries by Walter G. Bell. Churches provide a tangible link with Londoners, but so can books.

My copy of Fleet Street in Seven Centuries was originally owned by Enid F. L. Goodall who received the book as a present from her mother in February 1918. Inscribed on the inside cover of the book is “In memory of February 1918 E.F.S.G, C.E.G.G, F. Ln. G in Fleet Street” (the last set of initials were those of Enid’s mother).

On the top of the cover page of the book, Enid has written her name and the date Feb 25th 1918.

Finding the names of previous owners written in books is very common, however what was unusual about Enid is that she used her two middle initials so I wondered if I could track her down.

Enid was born on the 11th January 1890 in Dulwich. In the 1891 census her father Arthur was listed as a Photographer. In the 1939 census she had moved to Lowestoft in Suffolk where she is living with Hilda Allerton (a widow) and Georgina Unwin. Both Enid and Hilda are listed as being of Private Means whilst Georgina is listed as being in Domestic Service. Enid apparently stayed in Suffolk for the rest of her life as her death is recorded in Waveney in 1990, shortly after her 100th birthday. An article and photograph of her 100th birthday is in the Lowestoft Journal, I found the record but not the actual page which is held in the Suffolk Record Office.

So many millions of people have passed through the streets of London over the centuries and every so often it is possible to get a glimpse of an individual. It would be fascinating to know why Fleet Street on the 25th February 1918 was so memorable to Enid Goodall.