The next stop for my posts on the Netherlands is the city of Nijmegen. My father took a series of photos of the town centre and also the bridge over the River Waal, one of the bridges that was part of the 1944 Operation Market Garden – the plan for allied forces to breakout from Belgium, capture key bridges over the major rivers that ran from Germany and across the Netherlands to where an unobstructed route opened up to central Germany.

A brief bit of background to Operation Market Garden – By September 1944, the British 2nd Army and Canadian forces had made considerable progress. The breakout from Normandy was followed by a dash across northern France and Belgium to the point where the 2nd Army stood on the Belgium / Netherlands border. The speed of their success meant huge problems with supplies catching up with the leading columns, despite the apparent crumbling of the German forces.

With the American army making progress to the south, there was competition as to who would make the most progress into Germany and an ambition to try and bring the war in the west to a swift end.

Airborne forces had been waiting in England since D-Day. A number of proposed parachute drops had been cancelled at the last minute, often because the land forces had moved so quickly and had already taken the objectives.

Field Marshal Montgomery put together a plan which would make use of the airborne forces to secure bridges across the Netherlands and open up a path for the 2nd Army to sweep across the rivers to the point where a turn to the east would bring them directly into the industrial heart of Germany.

The plan was given the code name Operation Market Garden, with the ground forces being the “Garden” part of the operation and the airborne forces, the “Market” element.

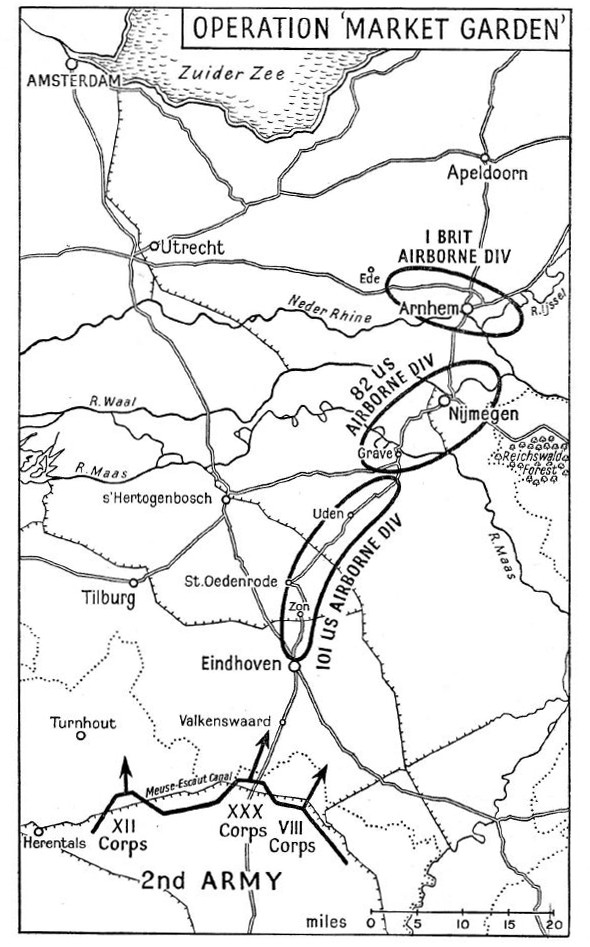

The following map from the 1958 book “Arnhem” by Major-General R.E. Urquhart illustrates the plan behind Operation Market Garden:

US airborne forces with drop and hold the route from Eindhoven to Nijmegen, with British airborne forces landing at Arnhem to hold the final bridge.

Operation Market Garden has been covered in a range of excellent books from the original “A Bridge Too Far” by Cornelius Ryan from 1974 through to the most recent book published this year, “Arnhem” by Anthony Beevor. There are also earlier books, some by those who were involved in the operation, such as the book from which the above map came from.

Operational Market Garden was the subject of the 1977 film “A Bridge Too Far”, directed by Richard Attenborough. There was also an earlier film from 1946, “Theirs Is The Glory”, which included many of the actual participants recreating their role in the operation at Arnhem. It is still available on DVD and a remarkable film to watch, given that the majority of those in the film were participants, not actors.

I can probably guess why may father wanted to see Nijmegen. Having followed the war as a child, using the Daily Express map of the War in Europe pinned to his bedroom wall – seeing the places that would have been featured in news reports, newsreels and post war films would be a thing to do, once travel was easier and he had completed National Service.

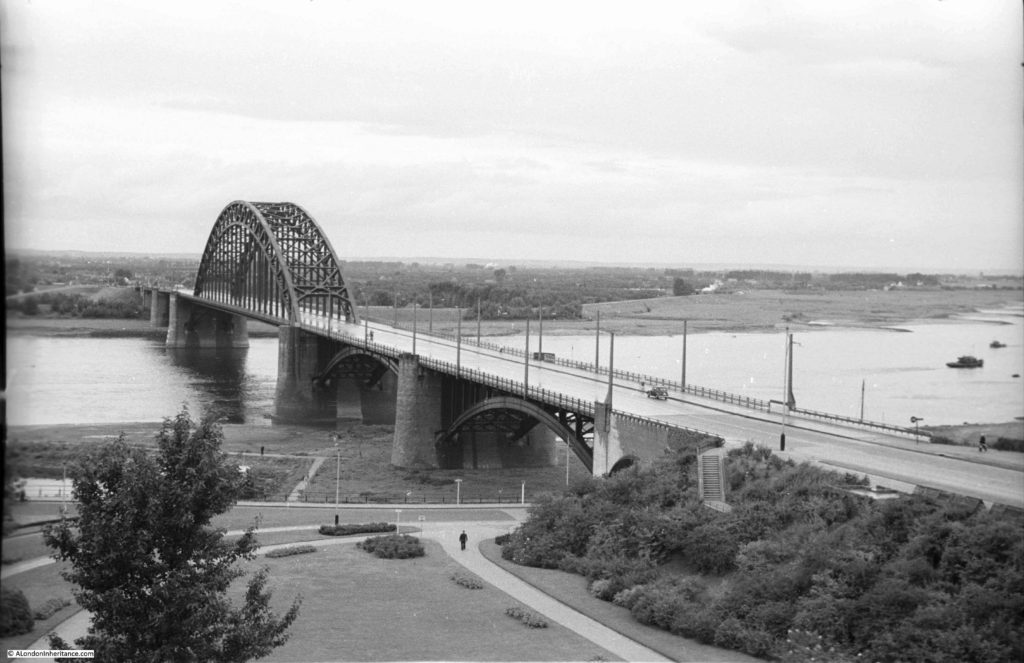

The bridges would have been the first things to see – this is the bridge at Nijmegen over the River Waal, a key part of Operation Market Garden. Photographed by my father in 1952:

Sixty six years later in 2018, I stood in roughly the same spot:

The 82nd US Airborne had been tasked with taking Nijmegen and securing the bridge as part of Operation Market Garden. They were to hold until the XXX Corp of the 2nd Army had fought up from the Belgium border, past Eindhoven to Nigmegen.

The bridge was important as by holding the bridge, and with XXX Corp reaching Nijmegen in time, they would have been able to move up to Arnhem to relieve the 1st British Airborne Division who were dropped near Arnhem to take and hold the bridge over the Nederrijn.

There was a significant delay in taking the Nijmegen bridge, which not was secured until day 4 of Operation Market Garden. An initial lack of priority to focus on the bridge, the need to defend the landing grounds, and from assumed German forces in the Reichswald Forest (see map above) meant that German reinforcements were able to build in the town and around the bridge. The Germans also started to demolish and burn large parts of the city of Nijmegen to make it harder for an attacking force.

Another 1952 view of the bridge:

The same view in 2018:

The attempt to take the bridge was made difficult as airborne forces had only been landed on the southern side of the river, rather than on both sides, so the north was well defended and attempts to take the bridge were met with heavy fire from the north.

Fighting in the city of Nijmegen was intense and took some days to clear. Rather than rush the bridge, US forces crossed the river to the west under heavy, sustained fire and taking significant casualties, and after more intense fighting were able to take the northern side of the bridge.

A small number of British tanks made it across the bridge, but then halted due to supply difficulties, no supporting infantry and unknown German forces on the road between Nijmegen and Arnhem. It was a surprise that the German forces had not demolished the bridge.

The final part of Operation Market Garden, the 1st British Airborne Division and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade at Arnhem were left isolated.

I had the opportunity to explore the Arnhem area, and witness the events that are held every year by the Dutch to commemorate the sacrifice of the British and Polish soldiers a few days after visiting Nijmegen.

In the above two photos, there is a grassed area at the bottom of each photo. Moving the camera down in 1952 and 2018 provides a view of a rather elaborate floral display

1952 above and 2018 below:

Nijmegen is probably the oldest city in the Netherlands, with a history of occupation going back to the 1st century BC. The city was established in the Roman period and given the name Noviomagus which means “new market” – as highlighted within the floral display.

On the northeastern corner of the city is a high plateau of land. This was occupied as a fortified area, with the town being established towards the south (where the town of today is located) and along the river. It is from the high point that the above photos were taken.

I then headed down to the bridge to take a walk to the centre of the bridge. The central carriageway is for motorised traffic, with walkways along each side of the bridge for pedestrians and bikes.

The Imperial War Museum archives have some photos which show the bridge immediately after the battle. The following photo is from the Nijmegen end of the bridge:

THE BRITISH ARMY IN NORTH-WEST EUROPE 1944-45 (B 10173) A column of lorries passes wrecked German vehicles on the bridge at Nijmegen, 21 September 1944. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205202526

The same view today:

Operation Market Garden depended on a long, relatively narrow thrust of allied forces up through the Netherlands. Whilst this allowed considerable progress to be made in penetrating deep into what had been occupied territory, it did leave long exposed flanks which the Germany army continually attacked, occasionally breaking the chain from the Belgium border to Nijmegen.

The allied forces therefore had to be continually ready for an attack from the east or west of their positions, as demonstrated by the following photo with guns facing the land to the side of the bridge.

THE BRITISH ARMY IN NORTH-WEST EUROPE 1944-45 (B 10171) 17-pdr anti-tank gun of the 21st Anti-Tank Regiment, Guards Armoured Division, guards the approaches to Nijmegen Bridge, 21 September 1944. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205202528

The Germans had rigged the bridge with explosives, but had held back from blowing the bridge in the expectation that they would need the bridge for a counter attack. There have been various theories for why the bridge was not blown when the capture of Nijmegen seemed certain – the wires were cut in the fighting, sabotage by the Dutch resistance, or just failed orders.

After the capture of the bridge, a considerable amount of explosive was removed:

OPERATION ‘MARKET GARDEN’ (THE BATTLE FOR ARNHEM): 17 – 25 SEPTEMBER 1944: NIJMEGEN AND GRAVE 17 – 20 SEPTEMBER 1944 (B 10174) Nijmegen and Grave 17 – 20 September 1944: British engineers removing the charge which the Germans had set in readiness to blow the Nijmegen bridge. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205193889

Walking further along the bridge and it was from roughly the following point that my father took some photos along the river and back into the city:

This 1952 photo is from the main road bridge, looking west along the River Waal towards the railway bridge:

The same 2018 view with a new railway bridge:

In 1952 this was the view looking back into the city of Nijmegen:

The same view in 2018, although with a lower water level on the river:

The water front has seen some development between the two photos, however the church, undergoing repair in 1952, can be seen in both photos, and along the front there are at least two buildings remaining. The second building from the left, along with the white building in the 2018 photo just below the church.

I mentioned earlier the Valkhof – the high plateau of land to the north east of the city, overlooking the River Waal. The area today is a park, with superb views of the river, but it has a long and fascinating history.

There is a deep cutting between the main part of the Valkhof and a steep hill overlooking the bridge. At the top of this hill is a building, with a plaque providing the following description: “Originally a defense tower from the 15th century. Substantially changed in 1646. Restored in 1888″

Large trees now obscure the view from where my father took the above photo, so I walked over to the tower and took a closer view. Today the main purpose of the tower appears to be as a wedding venue.

The Valkhof, the high plateau of land in the north east of Nijmegen, overlooking the bridge, has a fascinating history. Valkhof can be translated as “Falcon’s Court”.

Initially some Roman fortifications were followed at the end of the 8th century by a castle / palace for the Emperor Charlemagne who made Nijmegen one of his residences.

After Charlemagne’s death and towards the end of the 9th century Nijmegen is attacked by the Vikings and much of the palace destroyed. Over the following centuries, the castle went through periods of rebuild and decay until the 12th century when the Emperor Frederic Barbarossa ordered a much larger castle to be built on the Valkhof.

It is from the 12th century onwards that Nijmegen grows rapidly in prosperity and size. The castle and proximity to the River Waal provides the city with an importance in European affairs, along with access to a major trading route. Nijmegen is granted the privileges of a City which allows walls to be built around the city.

The castle was badly damaged in the 18th century when the French occupied the city, and at the end of the 18th century, permission was given for the castle to be demolished, with the exception of two chapels.

The castle and the city walls, overlooking the River Waal were an impressive sight. The following painting by the Dutch artist Frans de Hulst shows the castle on the Valkhof in the mid 17th century.

The following map from the same period shows the castle at bottom left with the city of Nijmegen enclosed by city walls and fortifications.

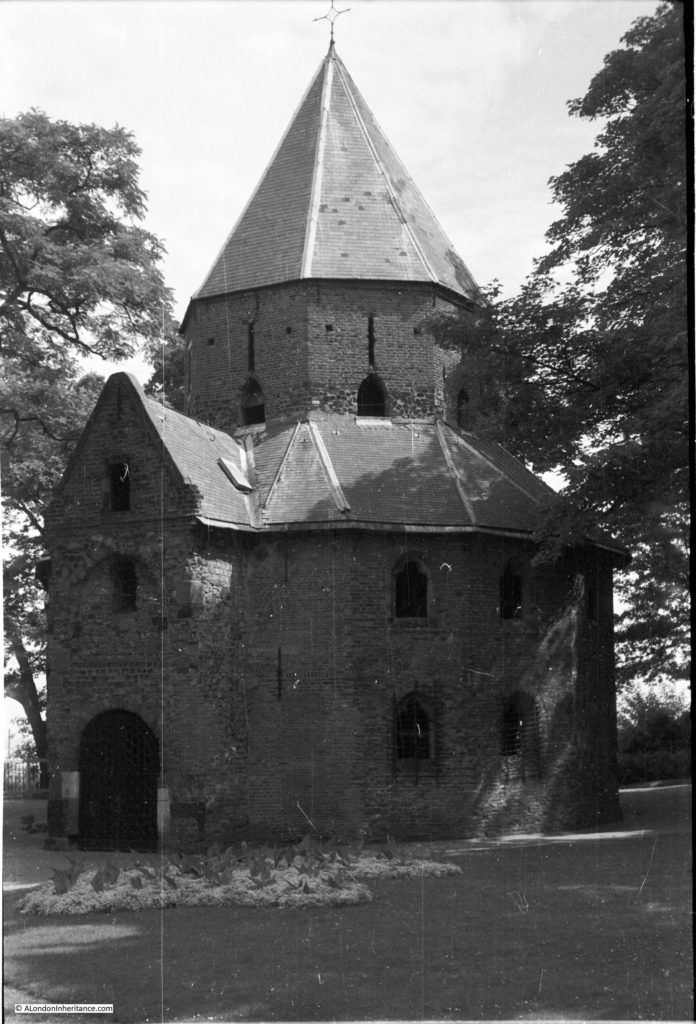

There are two structures remaining from the original castle on the Valkhof. The first is the chapel that my father photographed in 1952:

For a building that is hundreds of years old, the change in 66 years should be minimal, which indeed is the case, apart from some changes on the wall to the right of the main entrance, which may have been uncovering features which were bricked over.

Although the chapel dates from the very first castle on the Valkhof, the building today mainly dates from the end of the 14th century following a fire. This rebuild used brick, and the interior of the chapel was increased in height with an additional gallery running around the chapel.

To step inside the chapel is to walk from a 21st century city back into the medieval castle.

Some remarkable decoration still survives:

The other chapel on the Valkhof has only part of the walls remaining. This chapel dates from 1155.

There was only one 1952 photo that I could not find today. I assume it was in Nijmegen as the following photo was in the same strips of negatives. The photo shows a statue in a park with damage caused by multiple bullets.

I had a good walk around the park, but could not find the statue, or the scene behind which looks to be a bandstand.

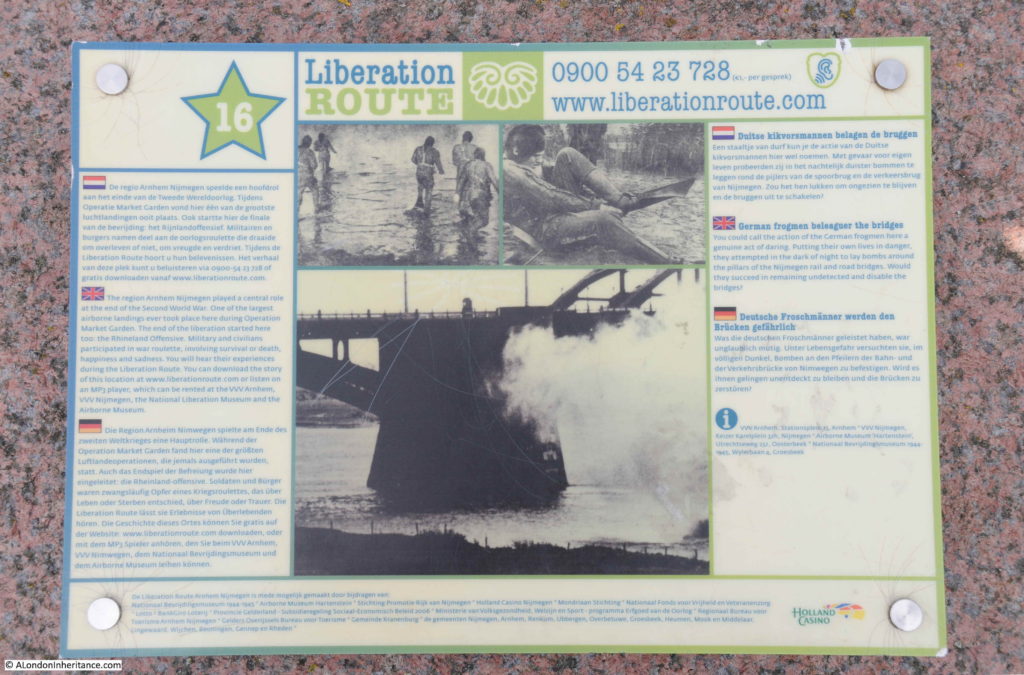

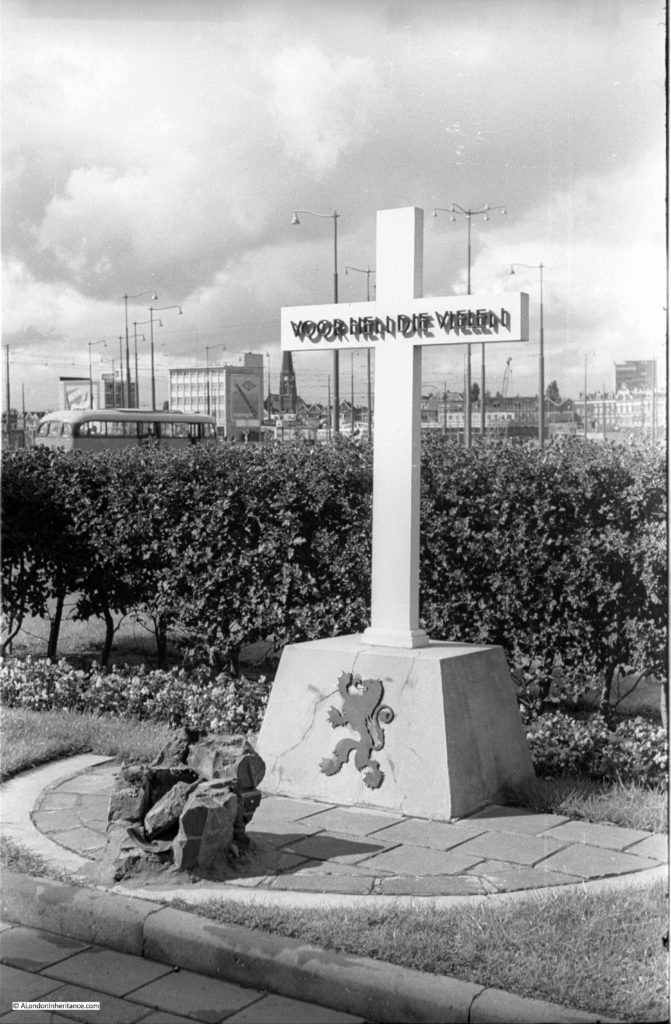

After exploring the Valkhof and the bridge, I took a walk along the edge of the River Waal, a circular route to head into the centre of Nijmegen to find the locations of the rest of my father’s photos. On the river edge is one of the Liberation Route information panels.

The Liberation Route Europe is a fascinating initiative. Funded by the European Union and the Dutch Foundation for Peace, Freedom and Veteran Support, the Liberation route aims to mark out key milestones in recent European history with the liberation of Europe at the end of the 2nd World War. The route starts in southern England, follows through the D-Day beaches of Normandy, the Belgian Ardennes and the southern region of the Netherlands. The route then moves through Germany to Berlin and ends in the Polish city of Gdansk,

Information on the Liberation route can be found at their website here. The site includes a large number of personal stories.

The website also has a copy of the Liberation Route’s “Magna Carta”, a document written by several European historians to establish the historical and scientific basis for the project.

The Magna Carta includes a summary of the impact of war on each of the European countries included in the route. This summary makes very clear that the impact, both during and in the decades that would follow the war, were and are very different.

For example, the following extract is from the summary for Great Britain:

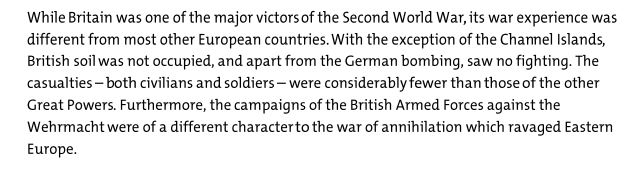

And the following is part of the summary for the Netherlands:

For the people of the Netherlands, it is the liberation from the appalling hardships outlined in the above text that are celebrated today, with the return of freedom and democracy that the liberation enabled. I would see how these celebrations continue to this day when I made the journey to the Arnhem suburb of Oosterbeek a few days later, where the final actions of Operation Market Garden played out.

Before that, I had some more locations of my father’s 1952 photos to find in Nijmegen – a subject for a post in a couple of day.