London changes at such a rate that it seems every time you walk down a street, there is new building work underway. I was recently walking down Charing Cross Road towards Trafalgar Square and saw scaffolding and sheeting around this building – Seven St Martin’s Place.

Seven St Martin’s Place is between the church of St Martin in the Fields and William IV Street and faces the Edith Cavell Memorial.

There is nothing very special about the building. It is a late 1950s office block with retail space along the ground floor. The company I worked for in the early 1980s had a couple of floors in the building.

What the building does have is a rather good location. Opposite the National Gallery, less than a minute’s walk from Trafalgar Square, at the southern end of Charing Cross Road and close to the Strand – a prime west London location.

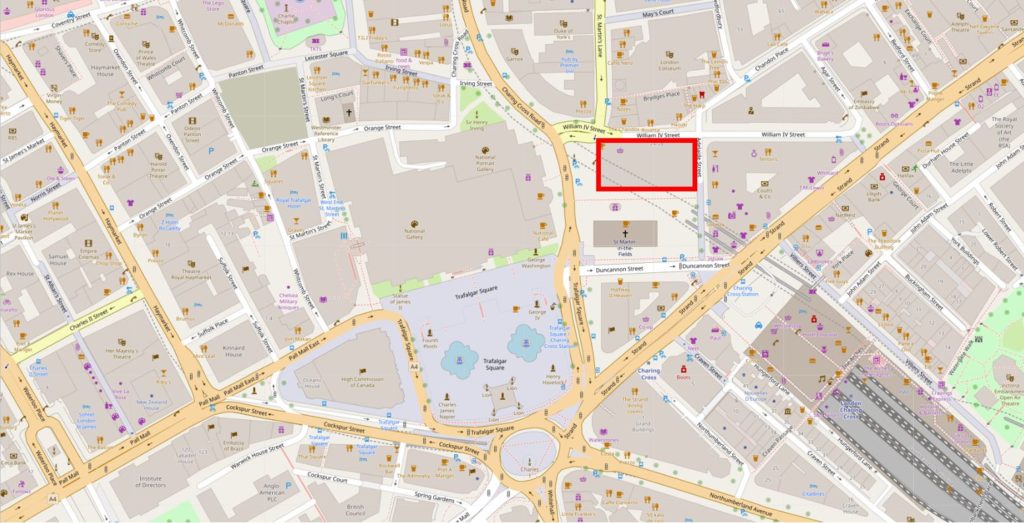

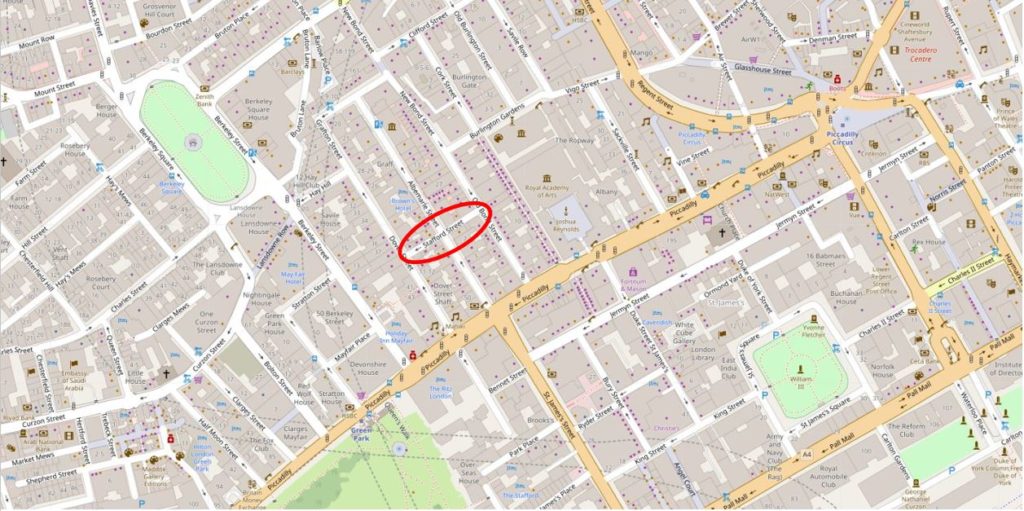

The location of the building is shown by the red rectangle in the following map extract (© OpenStreetMap contributors) .

The reason for the building work at Seven St Martin’s Place is that the building is being converted to a hotel.

The City of Westminster planning decision approves a change of use for the first to fourth floors from offices to hotel accommodation along with extensions at the fifth floor roof level to create a new rooftop restaurant and bar with external terrace,

The existing ground floor retail units will be reconfigured and new retail space created, both at ground and basement levels.

The hotel will consist of 136 bedrooms and be operated by the Butterfly Hotel Group, a Hong Kong based hotel company.

The redevelopment of Seven St Martin’s Place mirrors so much other development across London, where almost any property that becomes available, or can be purchased, is converted to either apartments or hotels. Not in itself a bad thing, providing that residential apartments are affordable, which is rare, or that the diversity of use found across London streets is not restricted.

The planning decision states that whilst “Policy S20 of the City Plan July 2016” resists the loss of offices to residential use, there is no policy that resists the loss of office space to hotel use. Apparently because it is also another use that generates employment, so providing the proposal meets regulations such as noise control, light, appearance, access etc. there is no reason to turn down the application, although an additional Policy S23 does state that existing hotels must be protected and that there are no adverse effects on residential amenity.

I suspect that with the demand for hotel rooms in London, very few applications are turned down.

Building name above the original entrance to the building:

The conversion of Seven St Martin’s Place did get me wondering about how many hotels there are in London and the level of growth as there does seem to be new hotels opening all the time, and at what point is saturation reached?

There are a number of reports available, and a report by London & Partners (the Mayor of London’s official promotional agency) titled “London Hotel Development Monitor – The Investment Hotspot” provides an overview.

The function of the agency is to promote London and the report is very much focused on promoting the city as a tourist destination and the opportunities for hotel development that tourism brings.

The report states that:

- In July 2018 there were 140,000 hotel rooms in London

- An additional 11,600 rooms were expected to be built by 2020

- Room occupancy is significantly high. In 2018, 79.6% of rooms were occupied, slightly behind Dublin (82%), but higher than Dubai (76.4%), Paris (77.1%), Berlin (74.7%) and Rome (70.1%)

An earlier report stated that the City of Westminster had the most hotels, with 433, with Kensington and Chelsea being second at 189. The City of London had 68 hotels.

The report highlights the impact of the 2012 Olympics on the number of hotel rooms opened across London:

- 2012: 8,133 new hotel rooms

- 2013: 1,833 new hotel rooms

- 2014: 5.442 new hotel rooms

- 2015: 3,117 new hotel rooms

The money involved is significant with the report claiming hotel investment in 2015 was £3.9 billion.

This level of growth and investment is expected to continue. A working paper “Projections of demand and supply for visitor accommodation in London to 2050” (Greater London Authority – April 2017) provides a projection of visitor numbers to London over the coming decades, with International visitor growth expected to be:

- 2015 – 18.581 million

- 2020 – 19.992 million

- 2025 – 21.215 million

- 2030 – 22.439 million

- 2036 – 23.907 million

- 2041 – 25.130 million

- 2050 – 27.332 million

Domestic visitors to London, staying overnight will also be growing significantly in the same period;

- 2015 – 12.938 million

- 2020 – 13.964 million

- 2025 – 15.451 million

- 2030 – 16.938 million

- 2036 – 18.598 million

- 2041 – 19.928 million

- 2050 – 22.413 million

Projections are notoriously difficult to get right, but I suspect it is safe to assume that the number of hotels required in London will continue to grow significantly, and there will be many more redevelopments of existing buildings over the coming decades.

The closed Post Office on the ground floor of Seven St Martin’s Place – will this type of business ever return to the retail space of redeveloped buildings, with probably increased rents? The planning decision does confirm that space will be available for the Post Office should the company choose to return.

The growth in hotels across London has been considerable, but to understand the impact on local communities, pricing pressure on the cost of housing, apartments and flats, costs for renting, we must also look at the growth of Airbnb in London, which has been dramatic over the last few years.

The Inside Airbnb site has some fascinating detail on the number and type of accommodation listed, cost, occupancy etc. The overview for London at the time of writing this post shows that for London there are:

- A total of 77, 096 listings, of which;

- 42,758 are entire homes or apartments

- 33,594 are private rooms

- 744 are shared rooms

The supporting data is downloadable. I was creating a graphic showing the number of Airbnb’s for each London borough, but ran out of time (I will add when complete), but for now, along with the new hotel being built, there are 9,411 Airbnb listings in Westminster.

The relative ease and low cost of global travel is driving the rise in tourism, and therefore the demand for accommodation in cities across the world. Other cities such as Venice and Barcelona are taking steps to control tourism, and the growth in Airbnb. These cities also have to manage the rise in tourists arriving by cruise ship – an issue which currently has minimal impact on London, apart from the occasional cruise ship moored by HMS Belfast or at Greenwich. Whilst these methods of travel do not require accommodation in the city, they do drive a high number of visitors who spend little in the host city.

Amsterdam is another city trying to manage ever increasing visitor numbers with a number of steps being taken including the Netherlands Tourist Board no longer actively promoting the country as a tourist destination.

The demand for land and buildings for hotel development is one of the many drivers behind the price of property across London.

In 2010, Seven St Martin’s Place was sold for £41 million and four years later in 2014 it was sold again, with the prospect of change of use to a hotel, for £65 million – a profit of £24 million in four years.

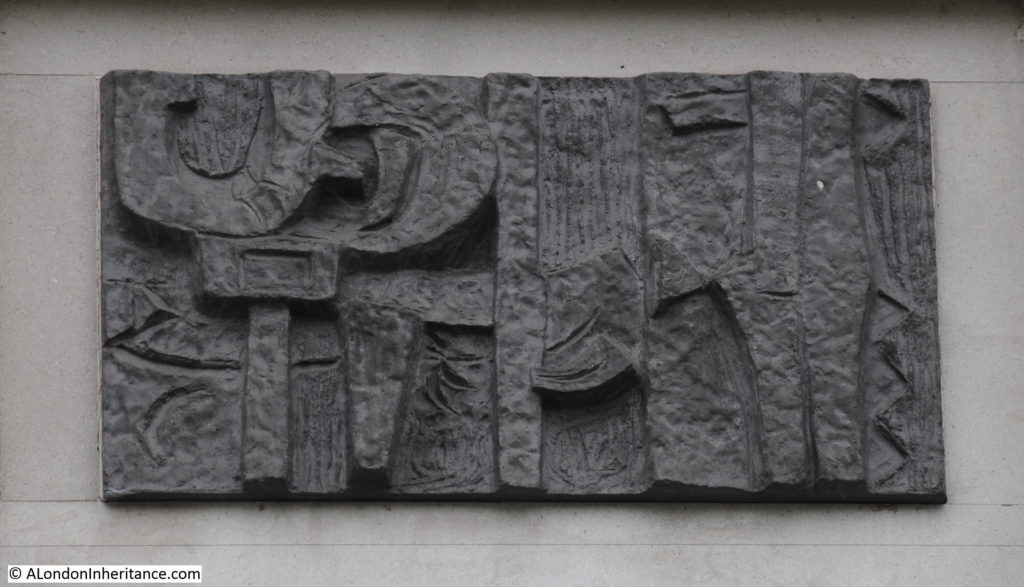

The facade of the building is relatively bland, however there is some interesting decoration on the side of the building facing the Edith Cavell monument. There are two vertical sets of, I am not sure what – artwork, carvings – one panel between each window, creating vertical columns of panels spaced between windows. See the photo at the top of the post for the location of these panels.

Close-up photos of these panels reveal some intriguing designs:

I have no idea as to the origin of these panels, or what they are intended to represent.

The building is not listed, and strangely the planning decision document which details the conditions of planning approval does not make any mention of these panels.

The drawings in the planning document appear to include these panels, so hopefully they will remain.

I have really tried to make out what these panels mean, but cannot find any reference, or looking at them, see any recognisable form or pattern.

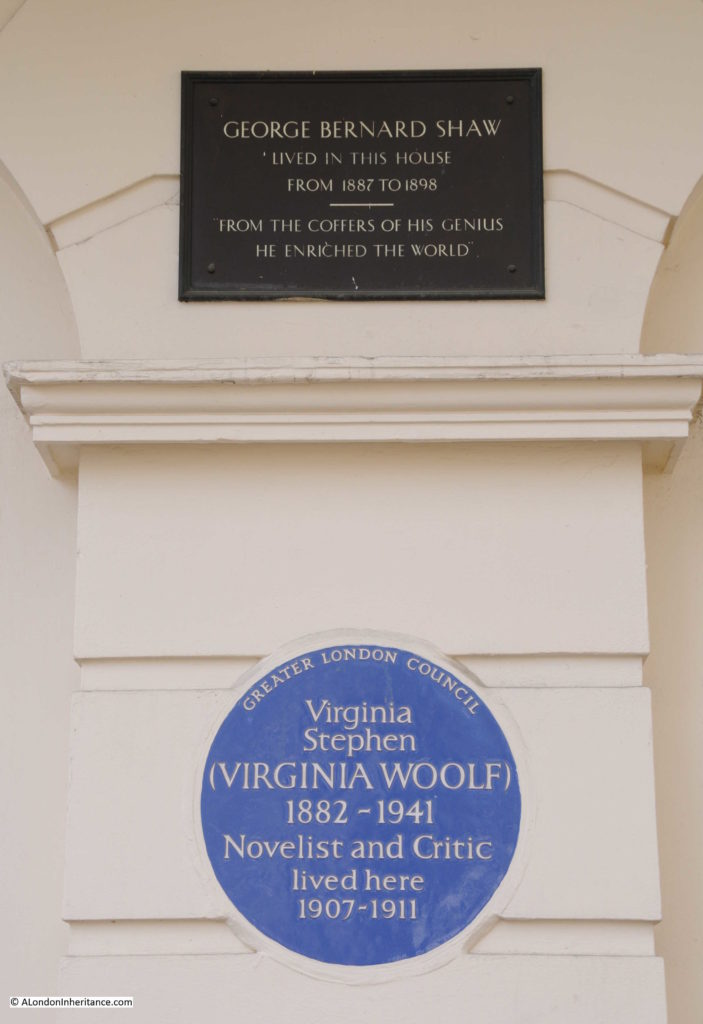

I did wonder if put together they would make a map. I have written about the building at 111 Strand, where a map of the area has been carved into the Portland Stone across the 1st to 5th floor of the building.

To see if they made a map, or if there was any other meaning when the panels are combined, I put them together in the same order as they appear on the building:

It does look as if the panels are meant to be combined. There are features that run from one panel to the adjacent. There looks to be a boarder around combined panels. On the far right of the panels, there are vertical wavy lines running down all four panels – could this be the River Thames?

Despite looking at these panels for ages, rotating the photos, trying different combinations, I cannot see any meaning – perhaps there is none. If anyone knows what they mean and who created them, I would be really interested to know.

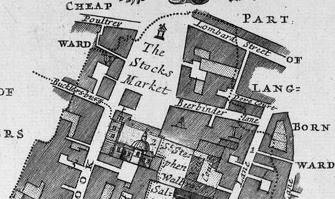

Although the focus of this week’s post was on the building, and what another hotel conversion means for London, I wanted to have a quick look at the history of the site.

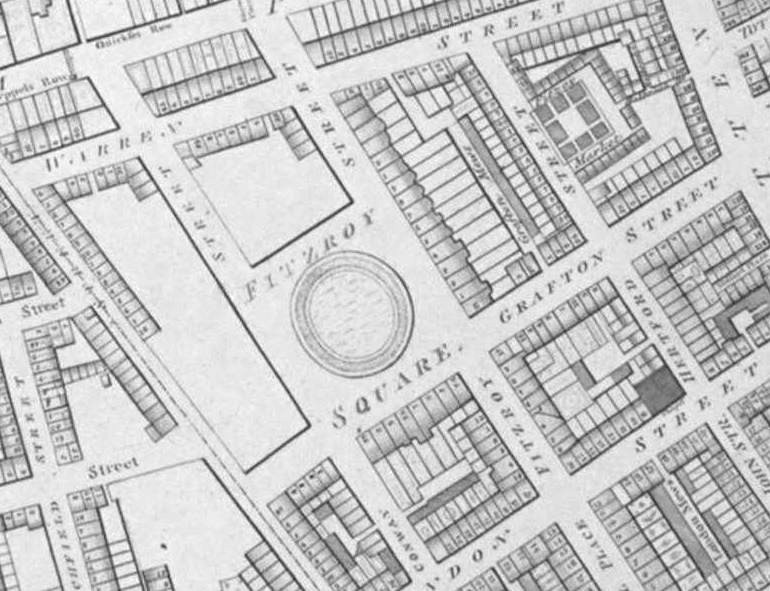

The area demands a full post, so this is a brief look. The 1895 Ordnance Survey Map shows the area as it was around 125 years ago:

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The street plan is much the same as today, but the block of land that is now occupied by Seven St Martin’s Place was St Martin’s Mews. The Vicarage remains to this day

What is interesting is that the location now occupied by the monument to Edith Cavell, also had a statue in 1895, however it must have been different as the Edith Cavell monument was unveiled in 1920.

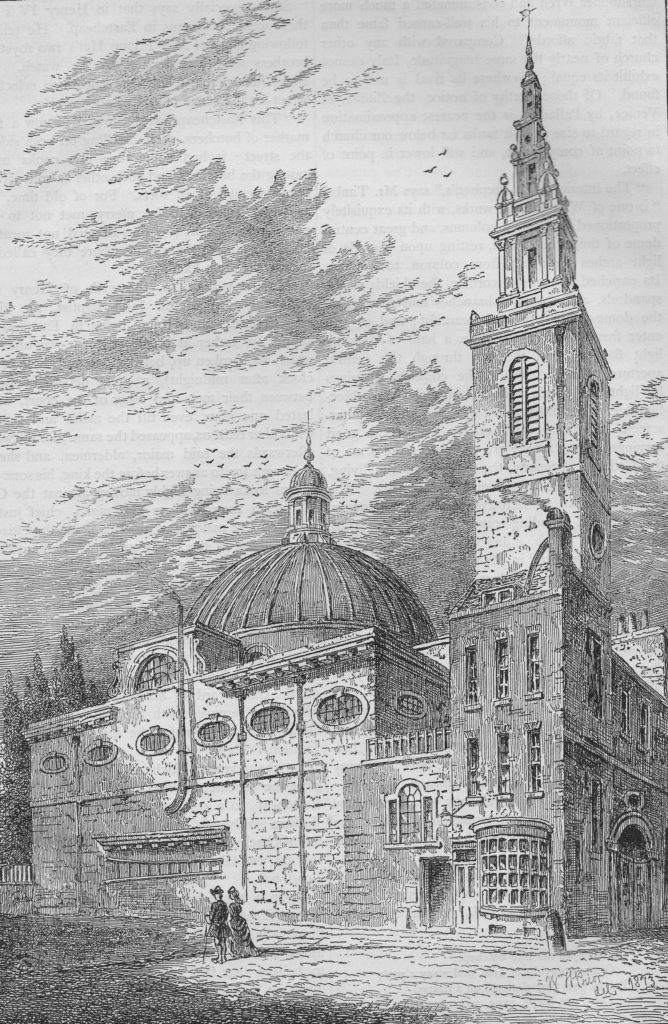

On July 18th 1902 a rather impressive statue to General Gordon, mounted on a camel was unveiled in the same position:

But this was seven years after the Ordnance Survey map – I could not find any reference to an earlier statue, but my research time was limited.

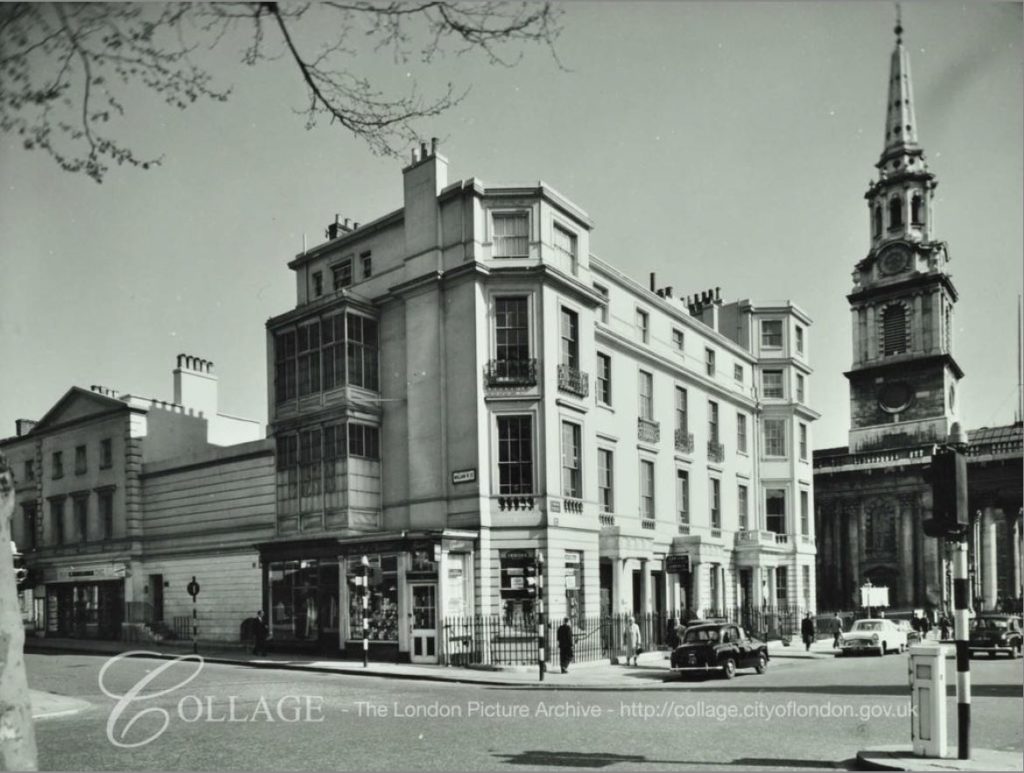

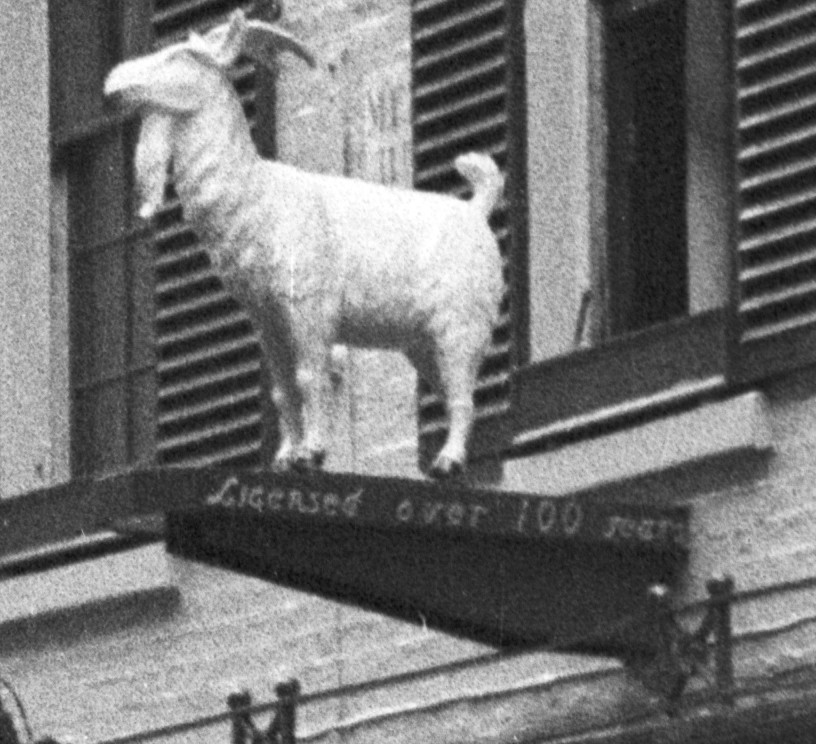

The London Metropolitan Archives Collage collection, as usual provided some views of the site prior to the construction of the building we see today.

This is the view of the building that occupied the site, note the entrance to the Mews. The photo is dated 1930 and I suspect are the same buildings that are shown on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_523_A7058

In the above photo, the darker section on the right of the block is the vicarage. This part of the block remains to this day and it is the lighter section on the left that was demolished to be replaced by Seven St Martin’s Place.

The following photo is a 1958 view of the building. As the 1895 map indicates, it was a collection of different buildings with a central mews.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_523_58_2190

As the above photo is dated 1958, it was either demolished soon after, or the references to the current building on the site being a late 1950s office block are wrong, and it is perhaps early 1960s.

The view of the building from William IV Street today, shrouded in sheeting as part of the building work.

Changes to London are gradual, and normally it is only the historically or culturally significant buildings that get publicity when their use is changed, or they are threatened, but there are also so many changes involving rather ordinary buildings from the last half of the 20th century.

Hotels and expensive residential buildings appear to be the main drivers of development, however there still appears to be an expectation for plenty of office space. The 2017 London Office Policy Review for the Greater London Authority projects that office employment across the greater London area will rise from 1.982 million in 2016 to 2.861 million in 2050, so office space will continue to be required in larger volumes to accommodate this workforce.

So with the 2050 projections for both office space and tourism numbers – London is set for a considerable amount of development over the coming decades, and we will continue to see change whilst walking the streets of London, although I am not sure how much trust I would put in future projections.