For this week’s post, it was a short walk after leaving last week’s location at Westferry Road, to find what remains of a street my father photographed in 1949. When sorting through his photos this was one location I was doubtful I would find. I did not recognise the scene and there were no clues to place the photo, apart from being taken from within what looks like a railway arch. I published the photo in one of my mystery location posts in 2015 and was really pleased when it was identified as Hardinge Street, just off Cable Street, a third of a mile east of Shadwell Station.

And this is the view from the same location today:

Hard to believe that this is the same place, however there are a number of clues. In addition to the obvious railway arch, in both photos the left hand section of the arch is fenced off, it was probably some form of workshop or storage area in 1949. There is access from the street to the fenced off area in both photos, and just past this there is another street leading off to the left.

There are also the sort of small details I love finding. On the pavement and kerb edge of the street, just before the street on the left there is a manhole cover on the pavement and a drain cover next to the kerb in the street. These are in the same locations in both photos – when the street above changes, often the utilities below the streets follow the same routes for decades.

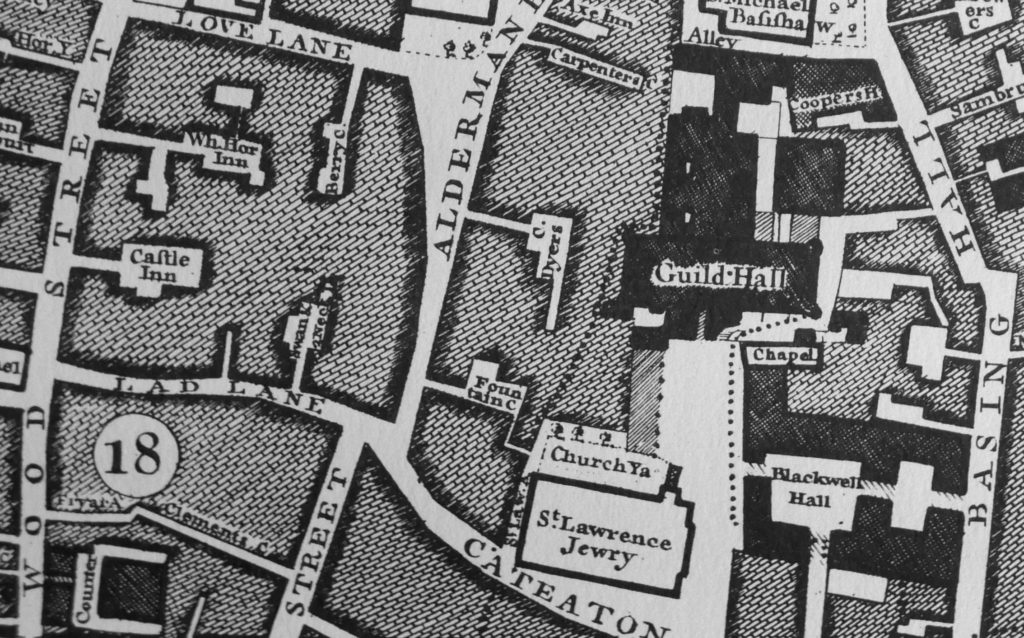

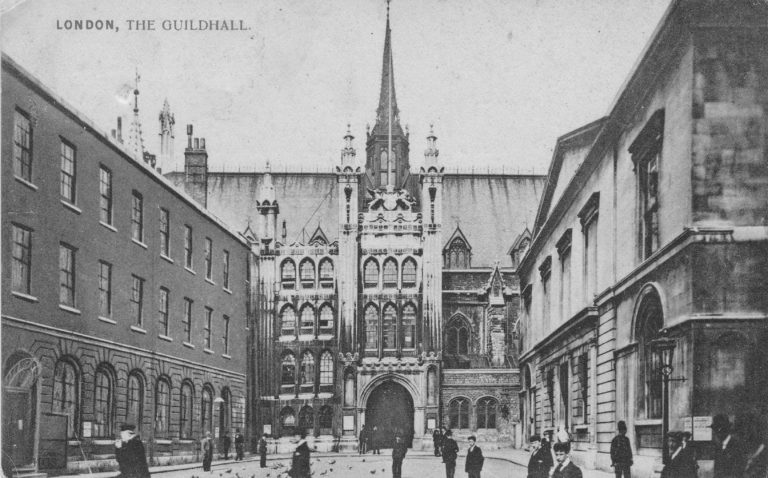

Hardinge Street is one of the many streets that ran between Cable Street and Commercial Road. The following extract from the 1895 OS map shows Cable Street along the bottom, Commercial Road along the top and in the centre of the map, Hardinge Street running between the two.

The railway, built in the late 1830s that runs into Fenchurch Street can be seen cutting Hardinge Street in two.

The streets are densely packed with houses, as can be seen in my father’s photo. The street on the left is named as Poonah Street in the map. The streets running off to the right can be seen in both map and photo.

Perhaps surprising is that the street looks intact after the heavy bombing east London suffered during the war. I checked the London County Council Bomb Damage Maps and the houses in my father’s photo are coloured yellow – “Blast damage, minor in nature”. the only exception is on the right side of the photo, the building on the corner of the street leading off to the right, there appears to damage and scaffolding. This building is coloured orange for “General blast damage, not structural”. A bomb must have fallen in the street leading off to the right as in the map there is a row of houses on both sides of the street coloured purple for “Damaged beyond repair” and black for “Total destruction”. It is the blast from this bomb that must have caused the blast damage to Hardinge Street.

The fate of Hardinge Street is very different either side of the railway. To the north, the view in my father’s photo, all the buildings, Hardinge Street and most of the side streets have all been demolished and replaced with the Bishop Challoner School. The map extract of the area today shows roughly the same area as the 1895 map and highlights how significantly the area has changed.

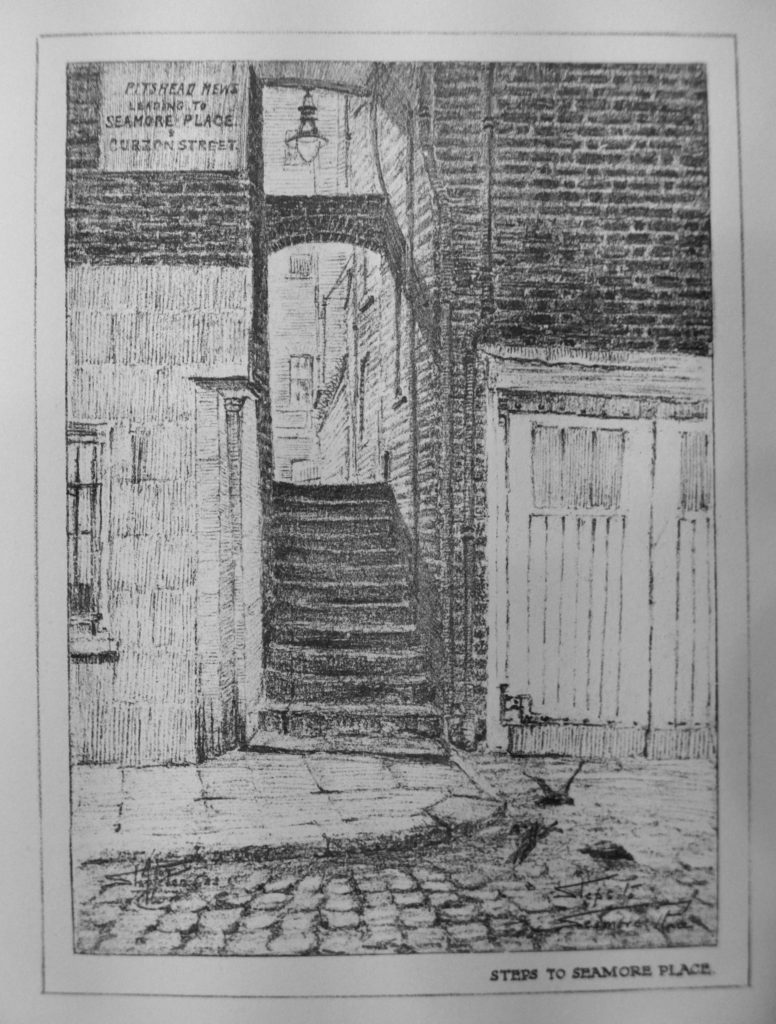

It is fascinating to trace the history of the area. Hardinge is an unusual name. I could not find any reference to why the street was given this name, however Poonah Street gave me a clue.

Poona was the name given by the British to the Indian city of Pune during the 19th century – I suspect the ‘h’ at the end was added as the pronunciation of the word probably ended with ..ah.

Following the Indian connection, Henry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardinge was Governor General of India between 1844 and 1848, so I suspect that when the street was redeveloped at some point between the 1850s and the 1895 OS map, it took the name of a Governor General of India.

Why do I say redeveloped? This is an extract from an 1844 map of the same area.

The name Cable Street had not extended for the full length of the street covered today – in 1844 this section was called New Road. What would become Hardinge Street is again in the centre of the map, but in 1844 was called Vinegar Lane. The railway is in the same position and comparing the map with later maps, Devonport Street on the right is the only street that has survived with the same name from 1844 to 2017. John Street on the left is now Johnson Street and next left, Lucas Street is now Lukin Street (and today follows a different route south of the railway).

To the left of Vinegar Street can be seen the Ratcliffe Gas Works along with the round symbols of gas holders. By 1895, the gas works had been demolished, Vinegar Street became Hardinge Street and the area was full of densely packed housing, corner shops and pubs.

Time for a walk around the area. The following photo is looking south, through the arches to the southern end of Hardinge Street. The location of my father’s photo and my later photo is just inside the arch to the right, up against the metal fencing.

This is looking at the corner of Poonah Street and Hardinge Street. In the 1949 photo this was the location of the corner shop.

A footpath can be seen to the right of the above photo. Although Hardinge Street as a road has now been cut off from Commercial Road, a footpath runs along the side of the school up to Steel’s Lane (another survivor from the 1895 map) and then to Commercial Road. The footpath is called Hardinge Lane, retaining the name, but Lane reflecting the loss of the through street.

Walking back under the rail bridge, south towards Cable Street, on the western side of Hardinge Street are Coburg Dwellings. The building dates from 1904 and was constructed by the Mercers Company. The name comes from the region of Germany where Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert was born.

In the above photo, there are a number of white plaques between the first and second floors of Coburg Dwellings. These are Mercers’ maiden property marks to show that the land and buildings belonged to the Mercers Company. A Mercers’ maiden in close up:

The Mercers Company is one of the oldest of the City’s Companies. The earliest mention of the Mercers is the appointment of the fraternity in 1190 as patrons of the Hospital of St. Thomas of Acon, On the 13th January 1394 the “men of the Mistery of Mercery of the City of London” were incorporated by royal charter.

The Virgin is part of the Armorial Bearing of the Mercers Company and was used for the Maiden property marks on Mercers’ buildings. Many of these can still be found across London.

The Armorial Bearings of the Mercers Company:

One of the entrances to Coburg Dwellings:

Another Maiden mark is on the building to the left of Coburg Dwellings, built as a Convent for the Sisters of Mercy:

Looking up towards the railway arches. As I explored the area there were frequent DLR and mainline trains passing over Hardinge Street:

On the corner of Hardinge Street and Cable Street is the building that was once the Ship pub:

The pub closed in 2003 and has since been converted into flats with an additional floor added to the top of the building. Fortunately a boundary marker from 1823 (which probably dates the construction of the pub) remains on the Hardinge Street side of the pub, between the ground and first floors:

Newspapers during the 19th and early 20th century included the usual adverts for staff at the Ship and also using the pub as a contact address for sales, however in 1893 there is a report which would have made the landlord very unpopular with the residents of Hardinge and Cable Streets:

“At the Thames Police court, London, on Wednesday, William Williams of the ‘Ship’ public-house, Cable-street, St. George’s was summoned at the instance of the Excise Commissioners, for diluting beer. and for not entertaining his permits in the spirit stock-books, and for not cancelling said permits, whereby he had rendered himself liable to penalties amounting to £200. The defendant pleaded guilty. Mr Mead fined him £35 for the dilution and £5 each for the other two summonses.”

His fines seem light compared to what the maximum penalty could have been, however I can imagine the reception he received back at the pub after having been convicted of diluting the beer.

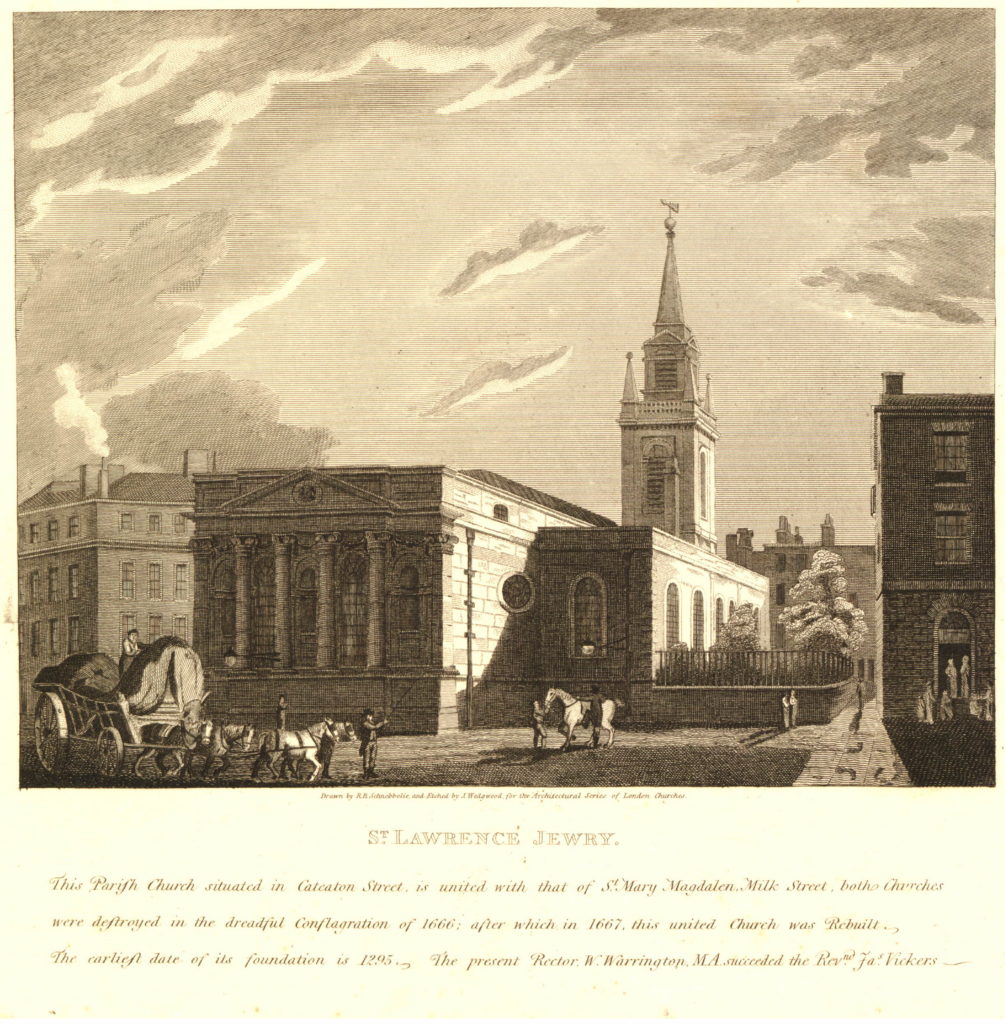

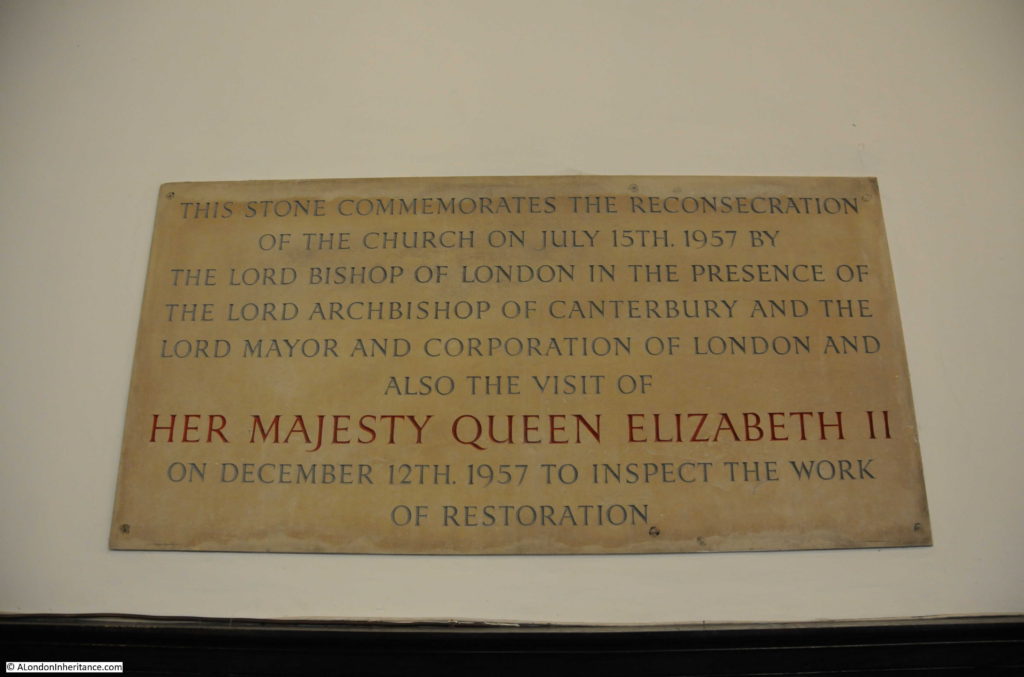

The church seen next to the pub is St. Mary, Cable Street. A relatively recent church having been consecrated on the 22 May 1850 to serve the growing population as the district developed.

After the church, I turned into Johnson Street. This street runs back up to Poonah Street to take me back to the location of the original photo. This is the view looking down Johnson Street:

The 1844 map had the location of the Ratcliffe Gas Works on the right of Johnson Street, filling in the area between Johnson Street and Hardinge Street, although there does look as if there was a narrow line of buildings along Hardinge Street.

When the use of gas for lighting and power started, the small scale of production and lack of large distribution systems meant that gas works would be built to serve a local area, very much within the centre of the area they were serving, even if that meant building a gas works in the middle of housing, or either side of a railway viaduct.

Gas works were dirty and dangerous places and would also produce fumes and smells that would blanket the local area. The following extract from the Essex Standard on the 31st October 1834 reports on an explosion at the Ratcliffe Gas Works:

EXPLOSION OF THE RATCLIFFE GAS-WORKS. On Tuesday morning, about five o’clock, a terrific explosion was heard to proceed from the Ratfcliffe Gas Works, which caused the greatest consternation and alarm in the neighbourhood. The inhabitants rose from their beds in all directions, and on proceeding to the spot, it was discovered that one of the large gasometers had burst at the back of the factory, adjoining Johnson Street and had carried away the outside case or vat in which the gasometer was placed, besides forcing down a brick wall, several feet in thickness, the materials of which were thrown in every direction.

It appears that the gasometer contained at the time of the accident not less than 16,000 feet of gas, and owing to the chive hoop, which binds the bottom of the tank giving way, the pressure became so great on the other parts of the gasometer, that it gave way, and sank with a tremendous crash on one side, forcing the gas out at the top, and splitting the massive timbers which composed the case, and the large upright beams which supported the whole fabric. Heavy pieces of timber were reduced to splinters and others forced to a considerable distance. A ponderous wheel, by which the gasometer was suspended, was hurled into the yard, a distance of 50 feet, and fell by the side of a man employed on the premises, who narrowly escaped destruction.

A stable by the side of the gasometer was blown in and reduced to ruins, the corn-bin, rack and everything were displaced, but singularly enough a horse within escaped unhurt.

After the explosion the place presented one mass of ruins – bricks, iron and wood lying about Johnson-street and the factory-yard in every direction. The damage is estimated at upwards of £20,000, but it is gratifying to add that no lives were lost, nor was any person injured; but if the explosion had taken place a few hours later, there is no doubt that a great many would have been killed, as Johnson Street is a very populous and much frequented thoroughfare, and several labourers were generally kept employed about the tank which burst.

Another gasometer only five feet from the other remained uninjured, which is accounted for by the great strength of the outer casing, which is formed of wrought iron, braced by large girders. A gas light in a lamp close to the tank was blown out; a circumstance which prevented the contents of the gasometer from being ignited, and probably saved property to a large amount from destruction.”

There are many other reports in the papers during the 19th century of the terrible fumes and smells that would come from the gas works, and of injuries to workers including the death of a worker during the construction of a new gasometer.

These were not good places to have in built up areas and the proximity to a busy rail viaduct cannot have helped. As can be seen in the 1895 OS map, the gasworks had been closed as part of the redevelopment of the area.

At the top of Johnson Street is this row of houses that have survived from the 19th century redevelopment of the area:

Again with a Mercers’ Maiden to show ownership. I assume that the Mercers owned the block of land that formed a rectangle between Hardinge Street, Cable Street, Johnson Street.

At the top of Johnson Street at the corner with Poonah Street:

The photo below is looking along Poonah Street towards the junction with Hardinge Street. In the above and below photos, the metal fencing that formed a boundary in the Hardinge Street arch can also be seen running along Poonah Street and to the arch in Johnson Street.

The Mercers Company owned the land before the railway was built and I suspect that the fencing shows the boundaries of the Mercers land as it is aligned with the buildings in Johnson and Hardinge Streets. This would explain why part of the area under the arch in Hardinge Street is fenced off – a reminder of land ownership from long before the railway was built, and that continues to this day.

To finish of this week’s post, here are a couple of extracts from my original high-resolution scan of the negative. I find the detail in these photos fascinating and as a reminder that it is not just the buildings that have long since disappeared, but also the people who made this area their home.

The following extract shows the left side of Hardinge Street. A woman with a shopping bag has possibly just been shopping in the shop on the corner of Poonah Street and Hardinge Street.

There is a large pram parked outside the terrace of houses and further along what could be two women, a small child between them and a pushchair.

And on the right of Hardinge Street, there is a pub on the corner, people walking along the pavement and what looks to be a couple of children underneath the scaffolding on the corner of the house.

Hardinge Street along with Emmett Street and Westferry Road in last week’s post have changed dramatically over the past seventy years. The people in the original photos, outside the newsagent in Westferry Road and those in Hardinge Street could probably never have imagined how much their streets would change.

I wonder what the next seventy years will bring?

alondoninheritance.com