There are some locations in London that have changed remarkably little over the last seventy plus years. There are also locations where decisions made 500 years ago are still in evidence. Not the usual candidates such as the Tower of London or St. Paul’s but amongst the ordinary streets of London.

One of my father’s photo’s from 1947 was the water pump in Bedford Row.

From Chancery Lane underground station, walk along Holborn to the west until you come to Brownlow Street. Head up this street and at the end you will be in part of Bedford Row, facing the water pump shown in the following 1947 photo:

And in 2015 the scene is remarkably much the same. The pump has been painted, a sign with the street name has been put on the building behind and there are now bollards around the pump.

The buildings behind are almost unchanged, even the metal fencing along the building to the right is the same.

The pump is also a perfect example of not always believing what you see in London. Take a look at the bollards and they are marked St. Pancras Street Works Department, 1826, so it would be a reasonable assumption that they have been in place since 1826, however the 1947 photo clearly shows a much smaller surround to the base of the pump and no bollards.

I assume that with the size of cars and lorries that are now in use on London roads, it was decided prudent to enlarge the base and provide some protection to the pump using bollards from some other location in St. Pancras.

I always find it fascinating to look at the buildings around any location I am photographing. On the building just to the left of the pump is the remains of the original street signage for Bedford Row:

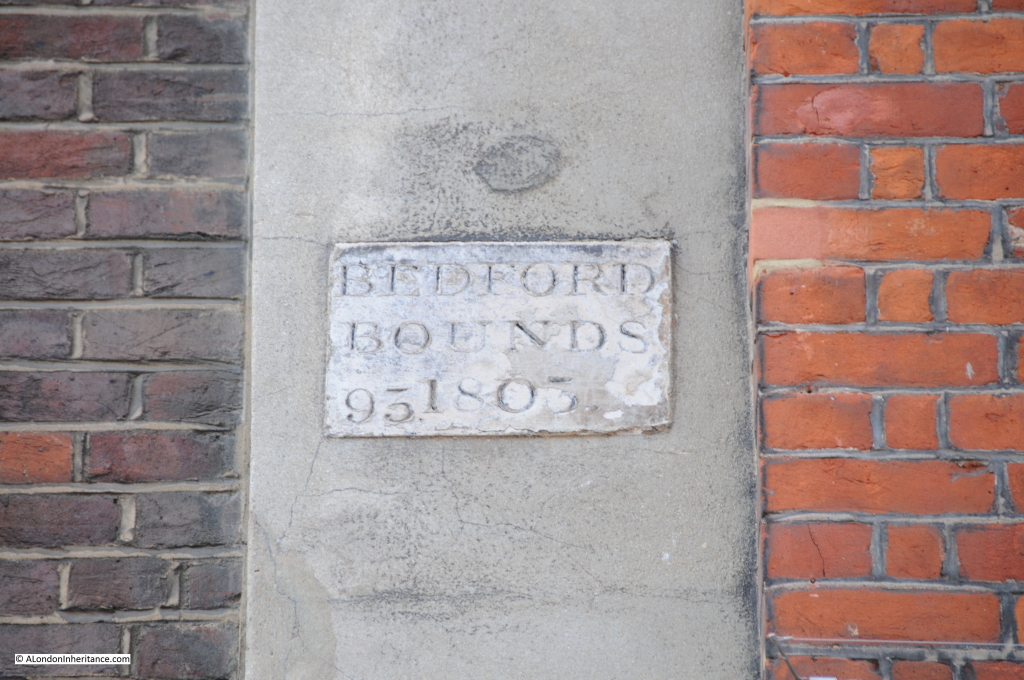

And just further along I found the following plaques:

Not so easy to read. The one on the left reads “Ms. Eliz Doughty 1824” and the one on the right “Bedford Charity Bounds 1824”

These are boundary markers and were essential to identify ownership of blocks of land prior to the availability of accurate street mapping. In the days before clearly defined ownership boundaries, when parcels of land were let and sublet, when it could be decades between the times when ownership of land needed to be checked and when owners could easily extend their boundaries in the hope of expanding their ownership before anyone realised, boundary markers played a key role in defining ownership.

Much of the land across London was originally held by the Crown or Church in large blocks, and over the centuries this has gradually been sold off to leave much smaller parcels of land, however some large estates still remain.

The Bedford Charity seemed an ideal candidate for some further research, to find the original boundaries of the estate, how the estate came into being, and if anything remained.

The origin of the Bedford Charity is a gift of land made by Sir William Harpur in 1566 to the corporation of Bedford.

Sir William Harpur was very much a self-made man of the times. The Harper family (the spelling of the name appears to have changed to Harpur around 1764) had lived in the area around Bedford for many years prior to the 16th century.

A school had been operating in Bedford since before 1166 and as with most schools of this period it was part of the church and Bedford school maintained this connection through to the dissolution during Henry VIII’s reign.

William Harpur attended the original Bedford School before leaving for London. His early days in London do not appear well documented, however from the book “The Harpur Trust” by Joyce Godber;

“It my be that he was apprenticed to a tailor, but there is no certainty about this; nor is there evidence of his connection with any other trade.”

The assumption of his original apprenticeship seems likely to be correct due to his later career, as William Harpur was admitted to the Merchant Taylors company in 1533.

Harpur’s progression through the Mechant Taylors resulted in him becoming Master in 1553, the same year he became an alderman for the ward of Bridge Without. When a vacancy appeared for an alderman within the much older and prestigious ward of Dowgate, Harpur was elected to this ward in 1556. He also served a year as treasurer of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and was a sheriff between 1556 and 1557.

His rise continued and in 1561 he reached the peak of his career becoming Lord Mayor of London.

Through his contacts, Harpur would have been very aware of the work of others within the City of London in support of schools throughout the country.

Whilst Harpur was Lord Mayor the Merchant Taylors school was founded by Richard Hilles, the master at the time and a contemporary of Harpur. He would have known of the founding of St. Paul’s school by Dean Colet in 1509 and the work being done by schools such as Winchester where the earliest printed school text books were compiled in 1559.

He had already been assisting the school in Bedford. Newnham Priory, originally attached to the school had been closed and the property confiscated. Again from “The Harpur Trust” by Joyce Godber;

“These were unsettled times in religious matters. In 1533 when he was approaching the age of 40, Harpur would have heard that, like monasteries elsewhere, Newnham Priory had been closed, the canons pensioned off, and the property confiscated. When he visited Bedford again he would find the priory site desolate, with much of the stone carried away and what was left was being converted to a house. At Bedford it would seem he found the school still existing, probably under an aged master, but it was clearly at risk, like similar schools elsewhere; for the building was up for sale with a number of other ex-monastic properties.

And now Harpur seems to have got in touch with John Williams, perhaps once his schoolfellow. Williams in 1545 obtained a large grant of former monastic property, and with it the school-house in School Lane.

In 1548 Edmund Green came from New College, Oxford to teach at Bedford. Probably Harpur arranged this and paid his stipend. But at this stage he did not commit himself further.”

Given his position in the City, he was probably a wealthy man.

Joyce Godber’s book also provides an insight into Harpur’s life as the Lord Mayor of London;

“On the 12th January, when Harpur and the alderman went to St. Paul’s and all the crafts in London in their livery, and then came into Cheapside a lord of misrule from Whitechapel with a great company”

and in September 1562 after an inspection of the conduit heads of London’s water supply:

“after dinner they hunted the fox, and there was a goodly cry for a mile, and after the hounds killed the fox at the end of St. Giles, and there was a great cry at the death, and so rode through London my Lord Mayor Harpur with all his company home to his place in Lombard Street.”

It would not be until 1564 that Harpur commenced the work that would provide a lasting endowment for Bedford.

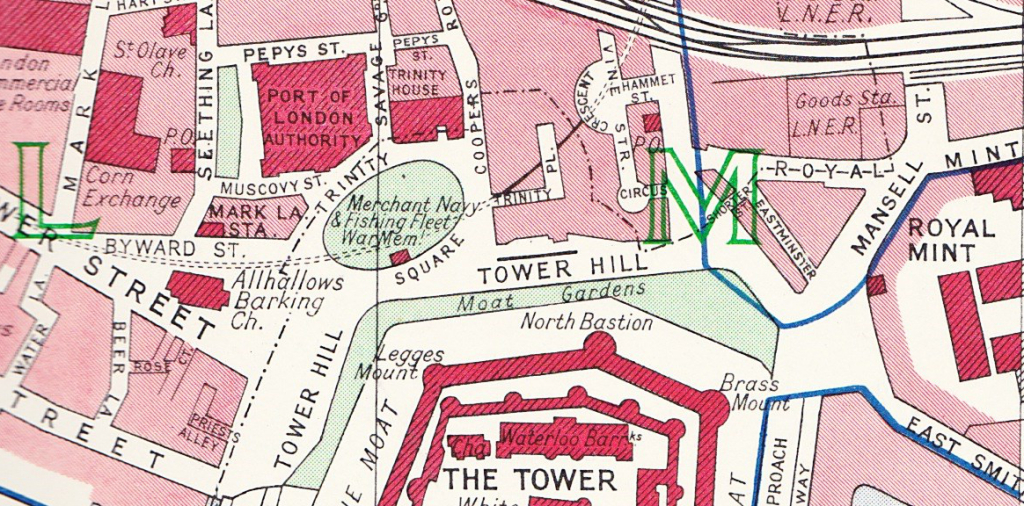

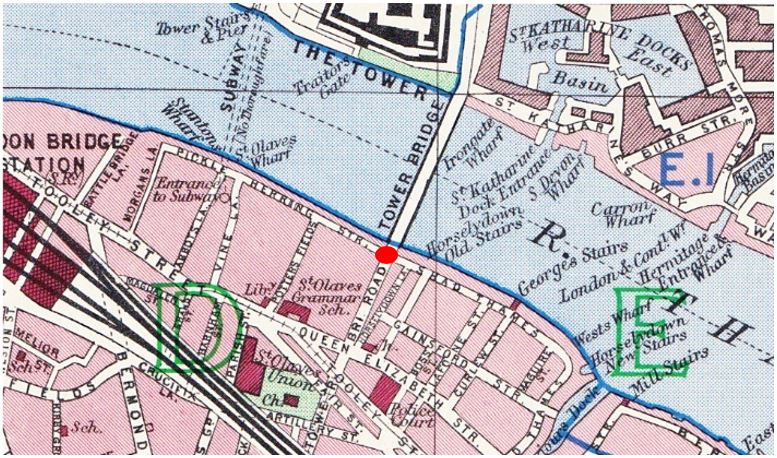

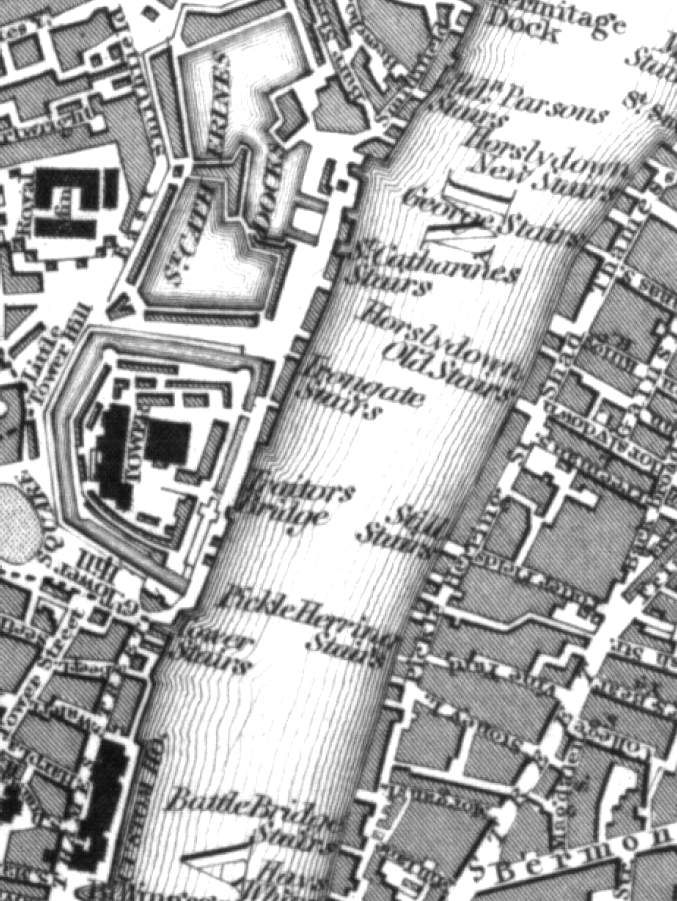

On the 30th September 1564 for £180, 13 shillings he purchased 12 acres and 3 roods of meadow outside the City at Holborn, old monastic land that had formerly belonged to Charterhouse.

On the 22nd April 1566 he and his wife, Dame Alice, conveyed the land to Bedford Corporation.

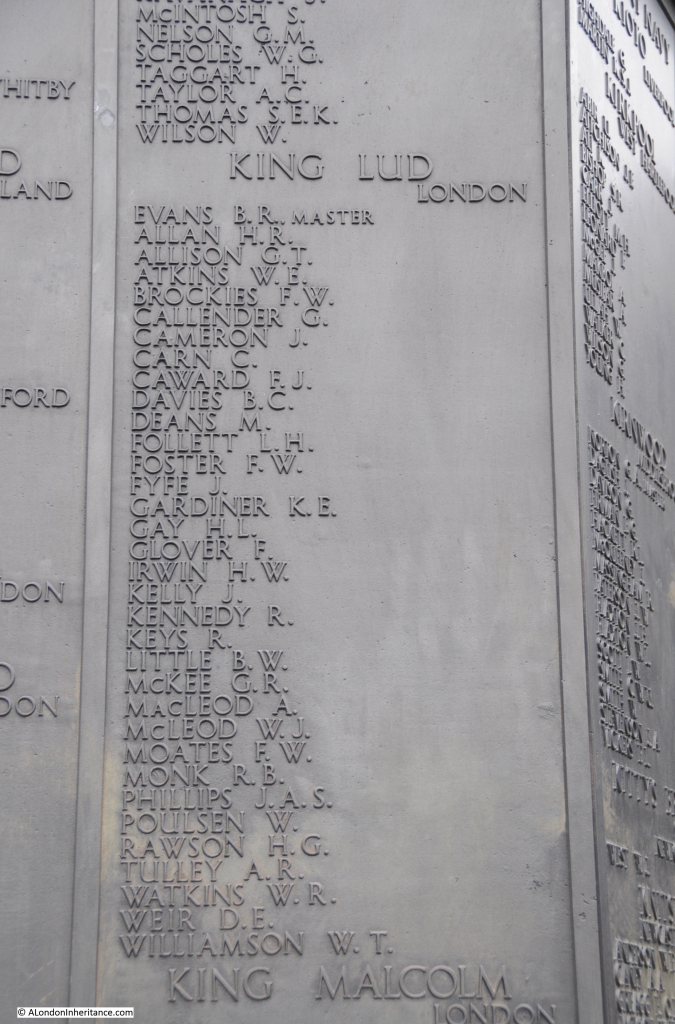

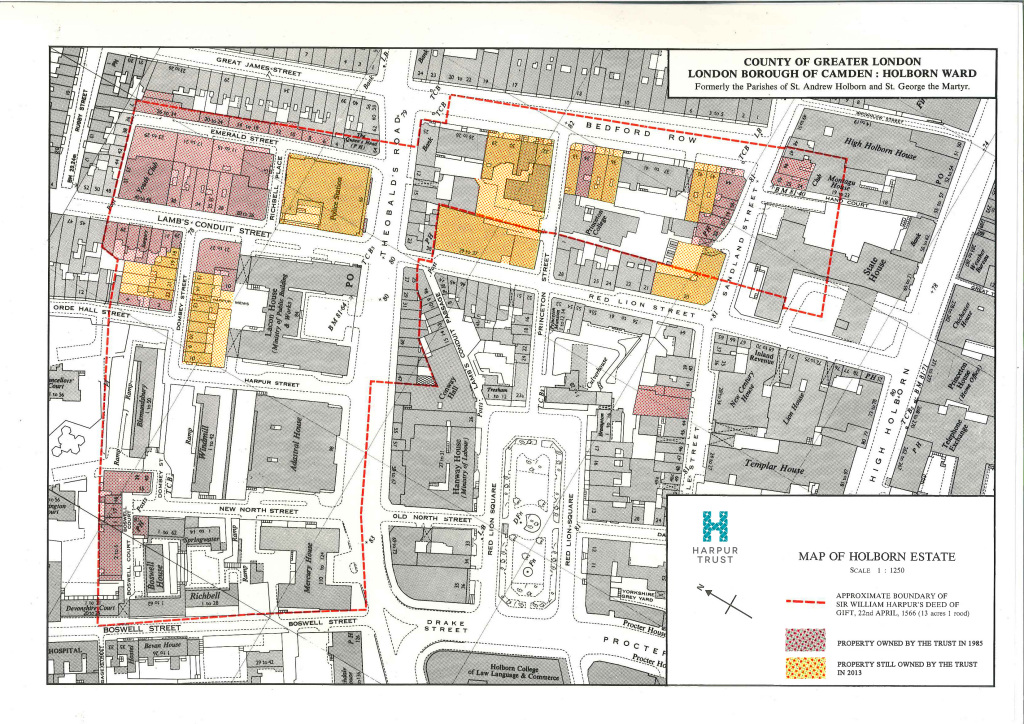

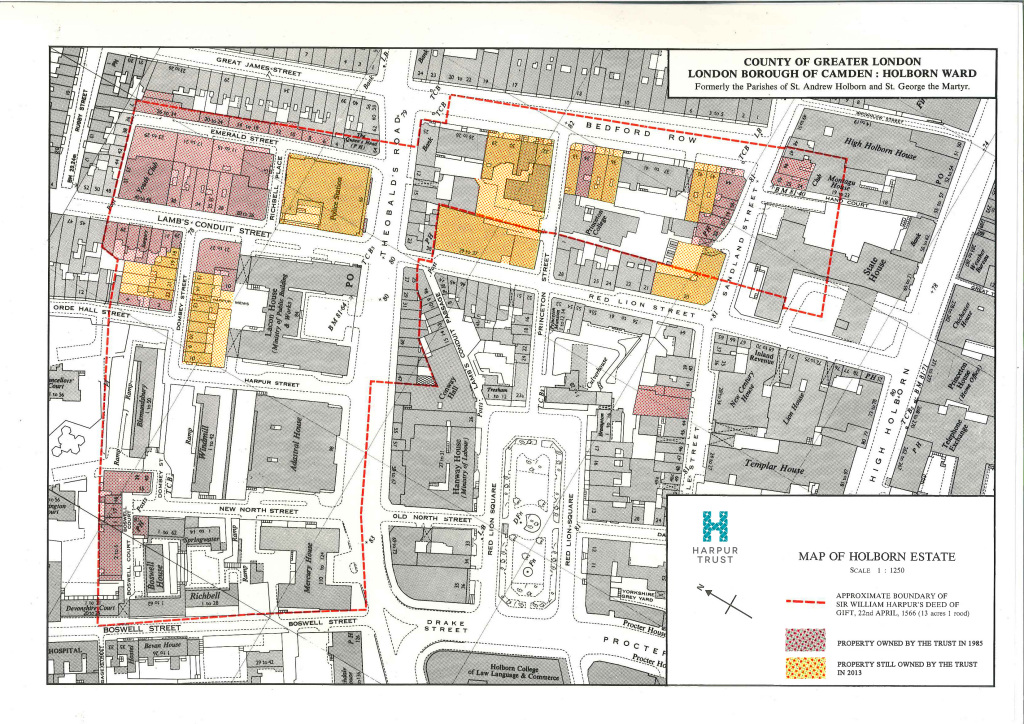

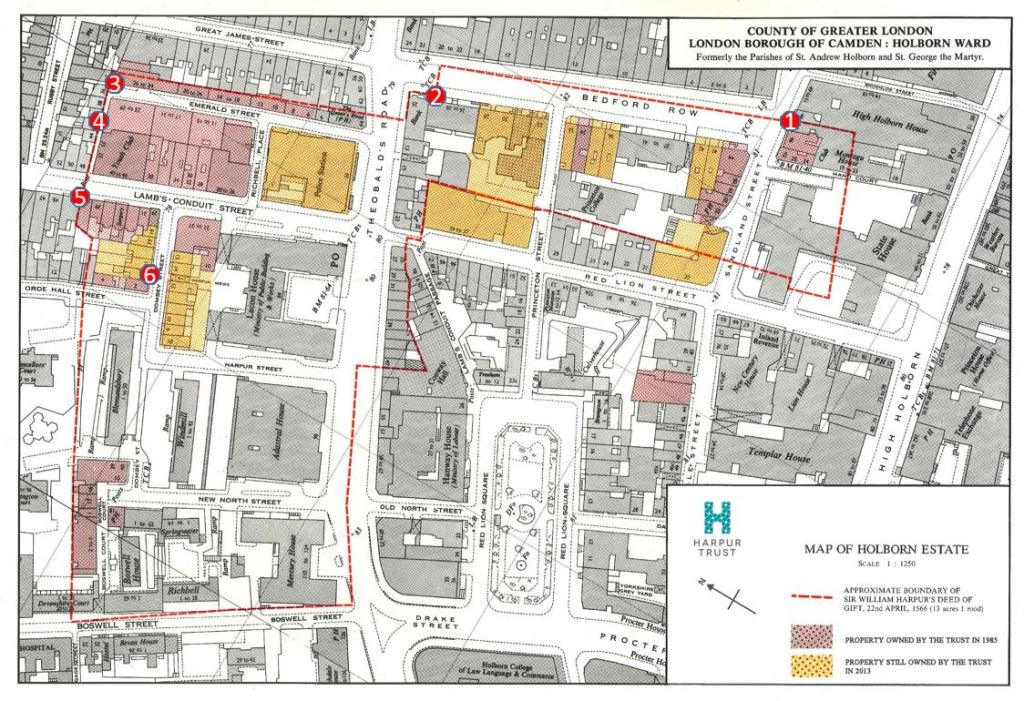

The following map (kindly provided by the Harpur Trust) shows the approximate boundaries of the original deed of gift by Sir William Harpur in 1566:

Whilst this map shows the majority of the original estate, it was not until 1654 when it took this final shape. There were some small blocks of land in Harpur’s deed separate from the main block and in a Chancery decree of the 16th February 1654 an exchange of smaller, detached parcels of land took place leaving the estate in its final form.

Whilst this map shows the majority of the original estate, it was not until 1654 when it took this final shape. There were some small blocks of land in Harpur’s deed separate from the main block and in a Chancery decree of the 16th February 1654 an exchange of smaller, detached parcels of land took place leaving the estate in its final form.

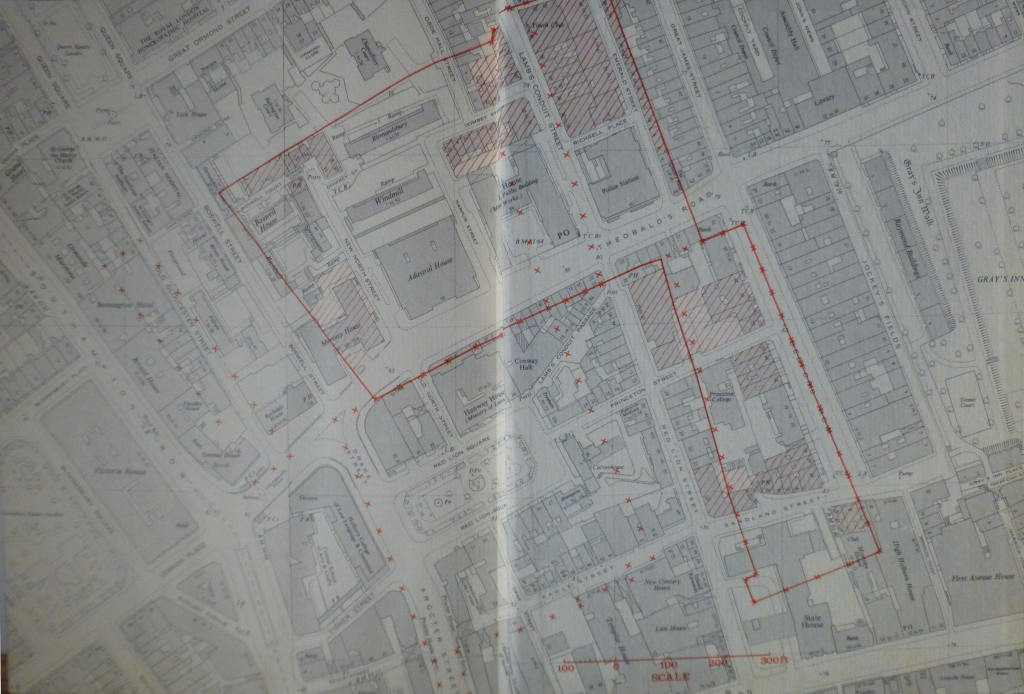

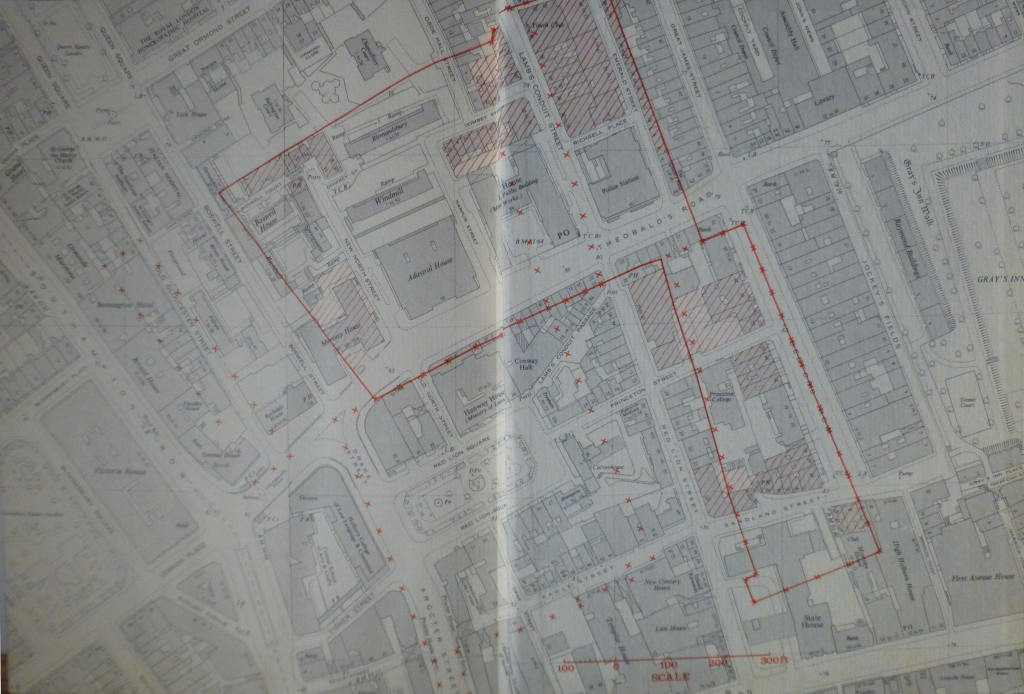

The following map from the Joyce Godber’s Harpur Trust book shows the original blocks of land identified by the red crosses to the left of the main block of land, which were part of the exchange to consolidate the estate into a single block.

Just prior to the transfer of the land to Bedford Corporation, in 1565 the land was let on a 40 year lease to Richard Bacon. On transfer, this brought in a sum of £12 per annum.

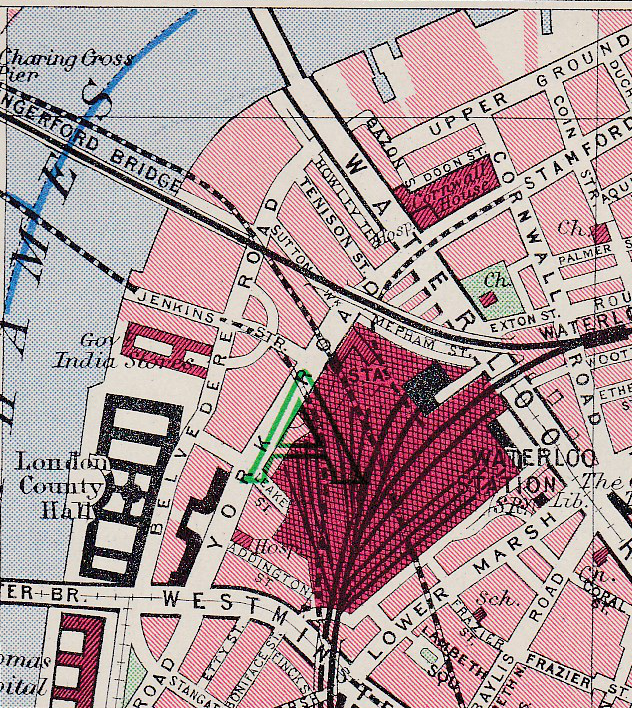

Having found the first boundary markers for the Bedford Charity, I wondered if any further remained and if it was possible to trace the outlines of a 1566 transfer of land, on the streets of 2015 London.

I started at the Holborn end of Bedford Row, with the water pump to my right. Bedford Row is a superb wide street of broadly similar architectural styles (despite the rather aggressively pollarded trees). Bomb damage during the war has been repaired rather than rebuilt.

From this point of view, the boundary runs down the centre of the street and the original Harpur land is to the left.

I made two visits to the area, one on a cloudy, wet day, the other with clear blue sky and a February sun which really highlighted the brickwork:

Due to the proximity of Grays Inn, many of the buildings now house activities associated with the legal profession.

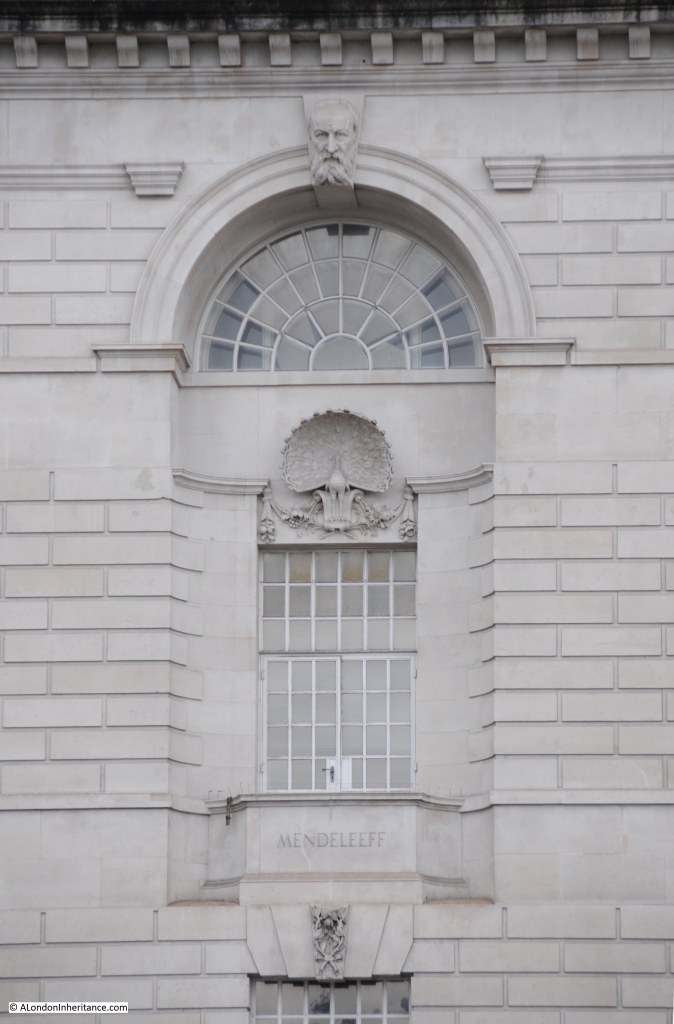

Although some buildings retain reminders of earlier occupation:

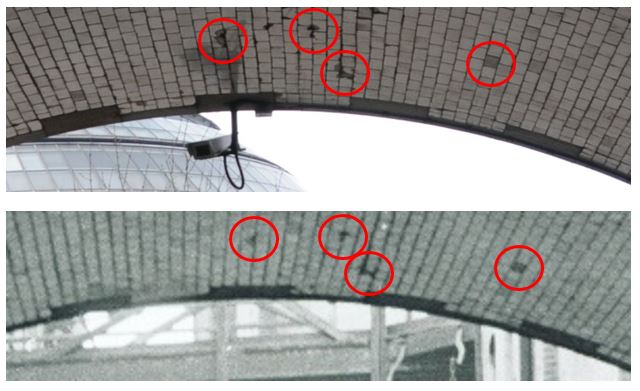

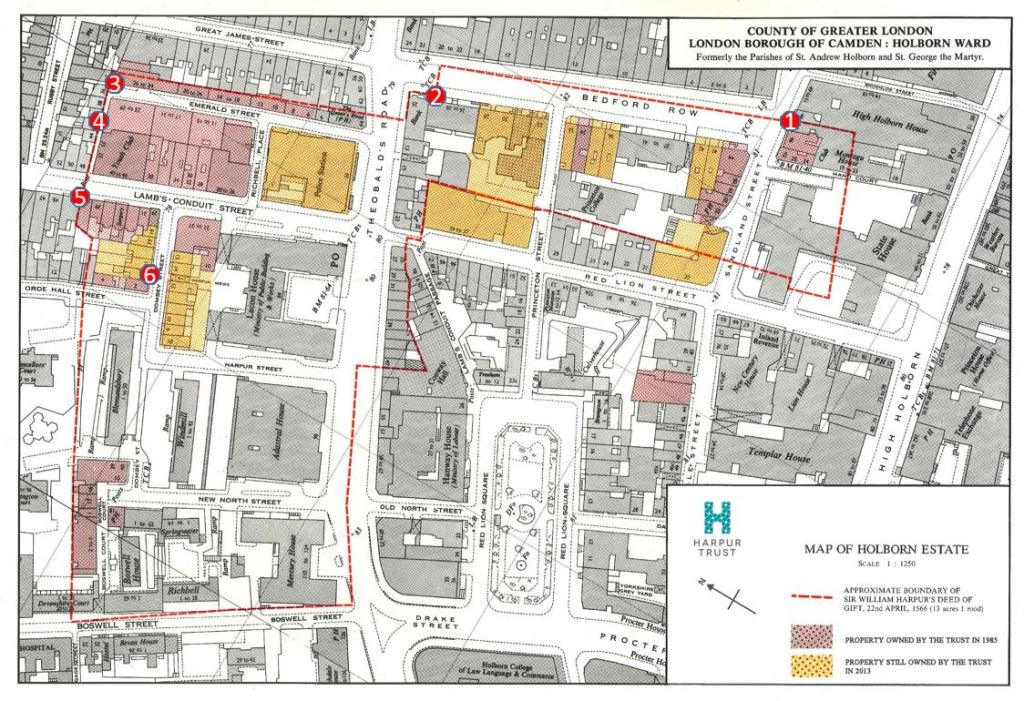

So how many indications of the original Harpur land could I find? I have annotated the Harpur Trust map with the locations of the boundary markers that I was able to find.

Marker 1 is the first, at the end of Bedford Row, adjacent to the water pump shown in the earlier photo:

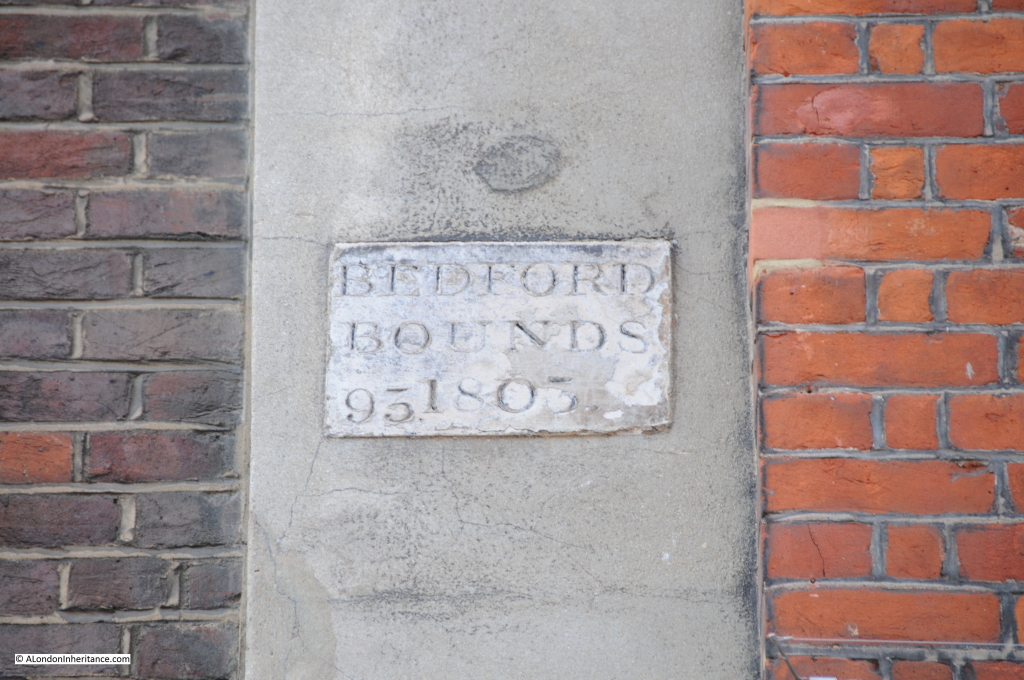

At the end of Bedford Row, at marker 2 in the map where I found the following from 1803 to show where the boundary came from the centre of the street onto the edge of the building.

This one is dated 1803. The different dates are down to the building work that was being carried out on the land, and when the commissioners of the charity would periodically come down from Bedford and “perambulate” the boundaries of the land.

Now cross over Theobalds Road and walk down Emerald Street. At the very end at marker 3 in the map is this boundary marker.

Now head down the small alley from Emerald Street, leading up to Lamb’s Conduit Street and half way along on the right are two of the Bedford boundary markers, one from 1776 and the other from 1838. These are shown in marker 4 in the map.

From Lamb’s Conduit Street we can look back down the alley (part of Emerald Street). Boundary marker 3 can be seen half way up the wall of the building at the far end of the alley. Marker 4 is half way along on the left.

Lamb’s Conduit Street derives its name from William Lamb who erected a water conduit n the site in 1577 by restoring an earlier dam in one of the tributaries of the River Fleet.

The next set of boundary markers are on a building in Lamb’s Conduit Street, directly across from the alley. These were from 1803 and 1838. Marker 5 on the map.

It is here that there is a marked boundary with another estate. Just below the Bedford markers on the building on the right is a boundary marker for the Rugby Estate, dated 1824. The Rugby estate was an 8 acre parcel of land that was part of a bequest to Rugby School in 1567. As with the Harpur estate, the Rugby estate was mainly meadow / pastureland at the time of the bequest, however rapid development over the coming years would add considerably to the estates income.

Photo taken from the end of the alley looking towards the building with the Bedford boundary markers and the Rugby marker on the building on the right. Not easily seen, but are just behind the tree branches.

The next pair of markers are strange. I cannot explain their location. Following the map, to get from Lamb’s Conduit Street to Orde Hall Street where I expected the next set of markers to be found, I found the pair shown in the following photo at marker 6 in the map. This area should be clearly within the Bedford / Harpur estate, however the marker on the right is Bedford 1883 and on the left is Rugby 1884. I can only assume that this was a later sale of land between the two estates in the later part of the 19th century, although strangely the Harpur map shows these buildings as being still owned by the Harpur Trust in 1985 and 2013.

Despite walking the rest of the route of the boundary I was not able to find any more boundary markers, although there are still a number of reminders of the Harpur legacy.

A small alley off Dombey Street leads to Harpur Mews:

And this is Harpur Street:

The far house is original and the house nearest the camera is a post war development.

An example of how boundaries between estates were often challenged can again be found in the book “The Harpur Trust” by Joyce Godber;

“There were soon to be more complications over the London lease. The Great Fire of 1666 set in motion a tide of building in London. One of the most active developers was Nicholas Bourbon, who had qualified as a physician, but who had speculative interests which included setting up in 1681 an office for fire insurance. A contemporary says that the trade of medicine failing, he fell into that of building, and the fire of London gave him means of doing and knowing much of that kind….All his aim was profit. By 1683 he had contributed to the development in the Strand, Soho and elsewhere. Another contemporary notes in his diary in 1684 on 11 June “Dr. Barebone, the great builder, having some time since bought the Red Lyon fields nears Gray’s Inn to build on….the gentlemen of Gray’s Inn, thinking it an injury to them, went with a considerable body of 100 persons, upon which the workmen assaulted the gentlemen and flung bricks at them. Red Lyon Field, now Red Lyon Square, adjoined the revised Harpur land on the southwest; between it and Gray’s Inn were trees and open space, now Bedford Row. the case came before the Privy Council, where it was said that Barbon marched about the fields at the head of his workmen, shouting and halloing.”

William Harpur died on the 27th February 1574 at the age of 77. He was buried in St. Paul’s church, Bedford.

The Bedford Charity is still going, renamed the Harpur Trust, and still using income from the properties owned within the original Harpur estate to support education in the town of Bedford.

Remarkable that 450 years later, Harpur’s original bequest continues to benefit education and can still be traced on the streets of London, and that going in search of a water pump can lead you off in a totally different direction of London’s history.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- The Harpur Trust 1552 – 1973 by Joyce Godber published in 1973

- My thanks to the Surveyor of the Harpur Trust for the provision of the map

alondoninheritance.com