This is the church of St. Andrew, Holborn, photographed in the low sun of a bright winter’s afternoon:

I will be exploring the church later in the post, but to start, let’s look at the location of St. Andrew, because I suspect the church is here due to its proximity to the River Fleet, and it is one of a number of London’s churches that are located at key boundaries, crossings and entry and exit points, of a much earlier City of London.

In the following photo, I am looking along Holborn Viaduct, towards the bridge over Farringdon Street, the old route of the River Fleet. Part of St. Andrew is on the right of the photo (the ornate tower is part of the City Temple Church, a much later Nonconformist church which is currently undergoing significant rebuilding works):

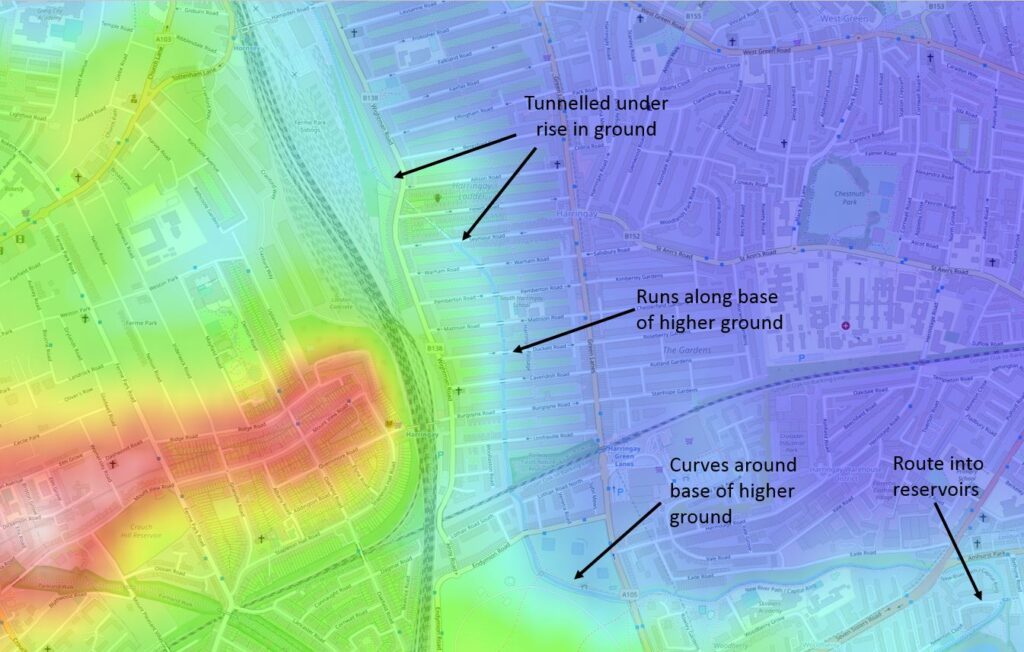

If we stand in what remains of the churchyard around St. Andrew, we can see that Holborn Viaduct is much higher than the churchyard, which marks the original surface level of the area. Today there are steps up from the churchyard to Holborn Viaduct:

And because of the height of Holborn Viaduct, a bridge is needed to take the street over Shoe Lane, which runs alongside the eastern boundary of the church, a view which again shows how surface levels have changed around the church:

A short walk east from the church, and we can look over the bridge down to Farringdon Street, a view which shows the height difference between the upper road, and the original route of the River Fleet (which would have been lower than the current road surface due to building over the original water course):

The bridge over Farringdon Street is part of Holborn Viaduct, the 427m long viaduct designed to provide a bridge over the valley of the Fleet River and a level road between Holborn Circus and Newgate Street.

The construction contract for Holborn Viaduct was awarded on the 7th May 1866 and on the 6th November 1869 it was opened by Queen Victoria. One of the many 19th century “improvements” to the City, designed to address growing congestion along the streets, and to build a City that mirrored London’s global position.

Before the construction of the viaduct, there had been a hill which ran down from Holborn, down to the original route of the Fleet.

To get the level street surface of Holborn Viaduct, with sufficient clearance for the bridge over Farringdon Street, the level of the street needed to be raised, and is why the street is now higher than the churchyard around St. Andrew’s.

The church also lost part of the churchyard, as the new Holborn Viaduct was much wider than the street running down the hill, that it had replaced.

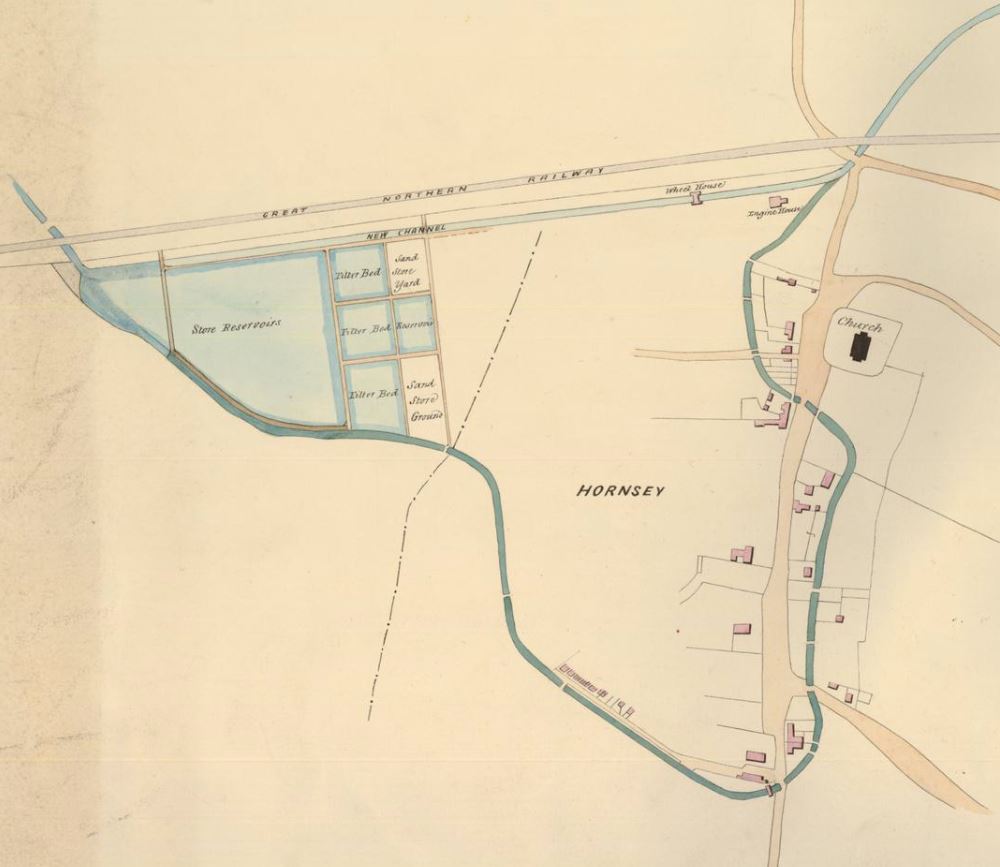

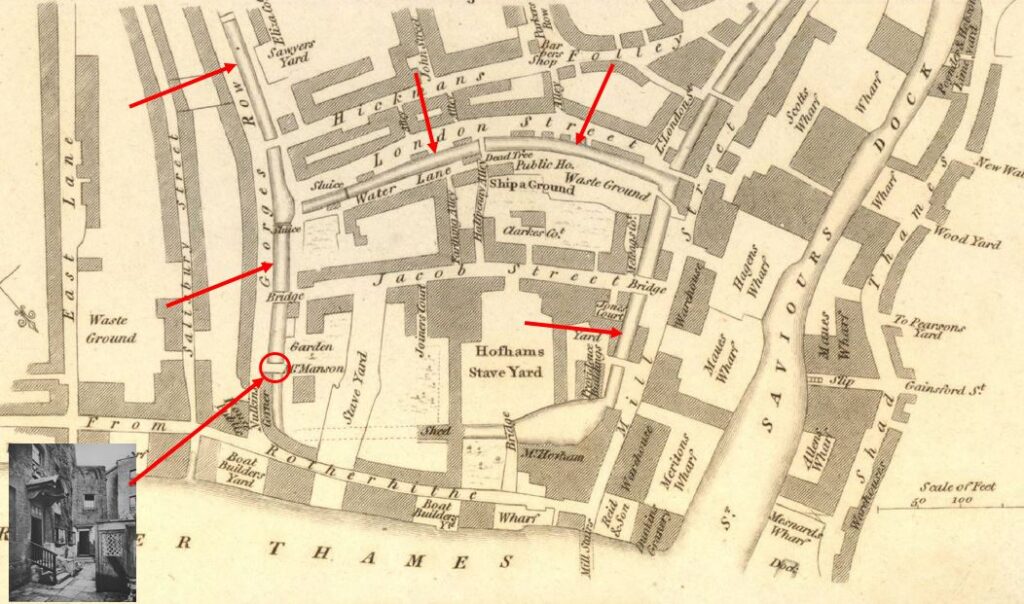

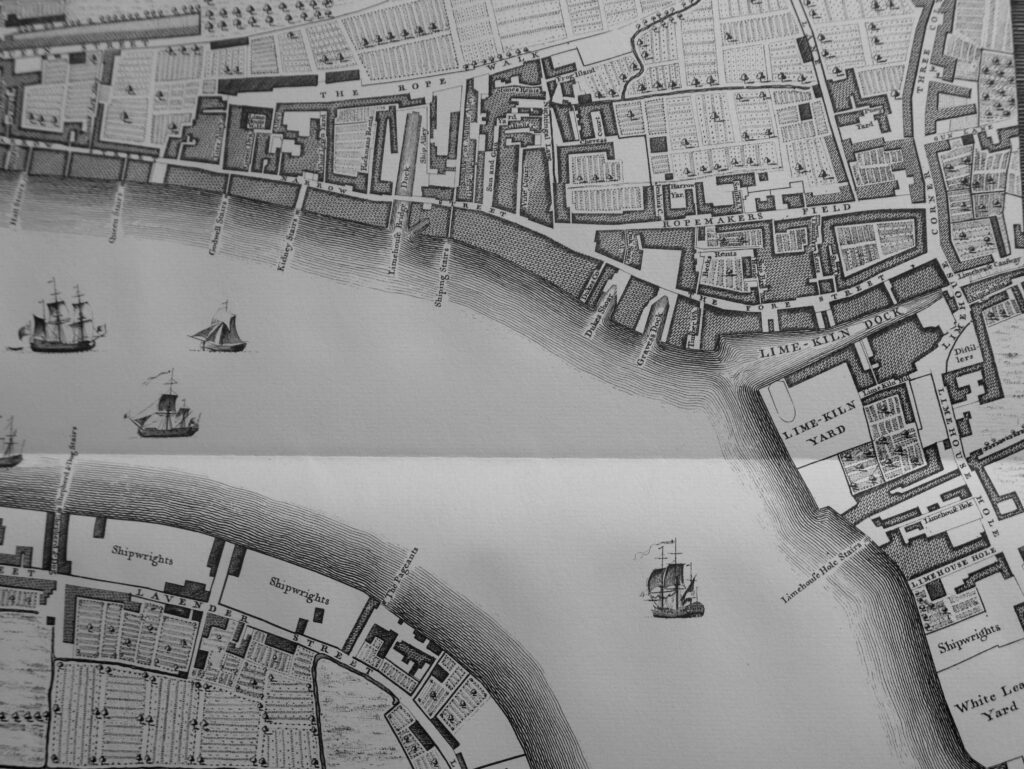

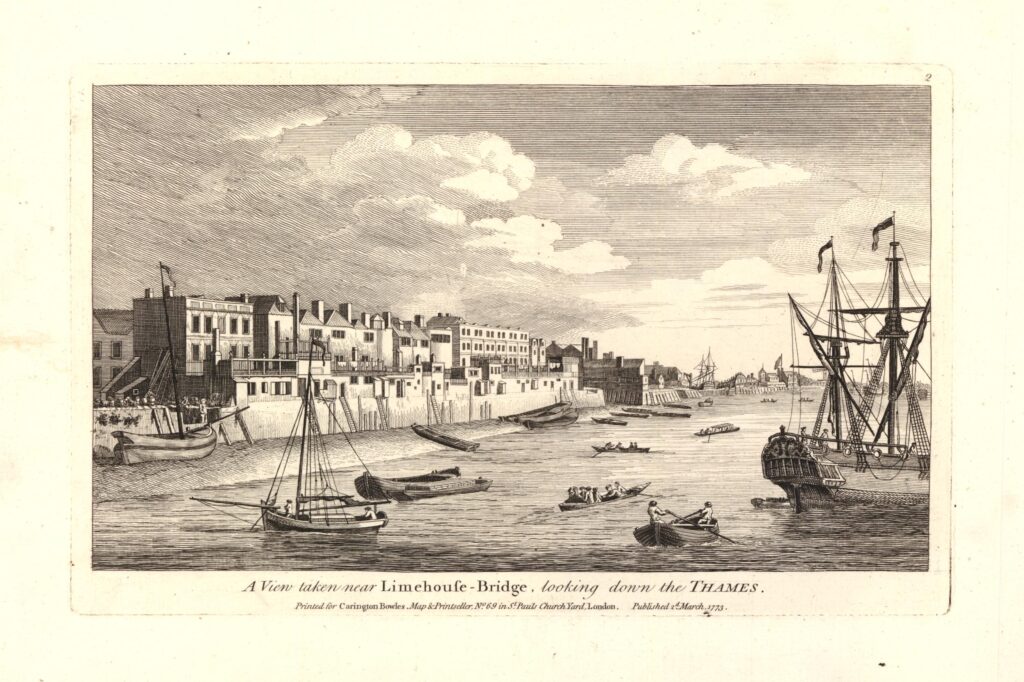

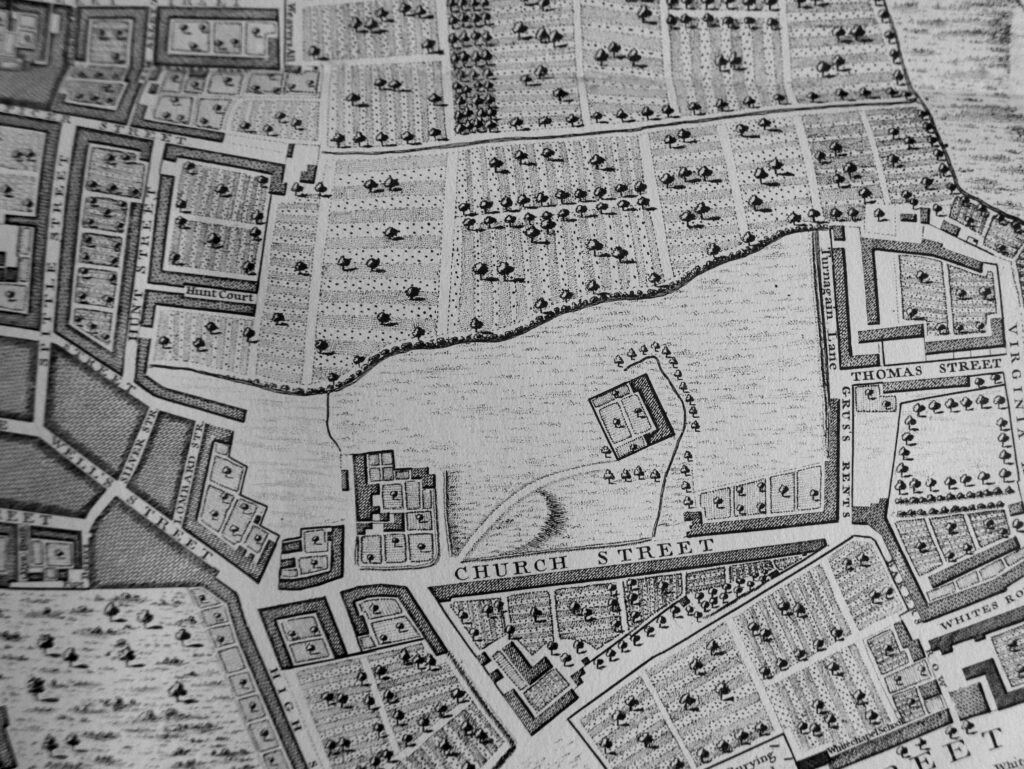

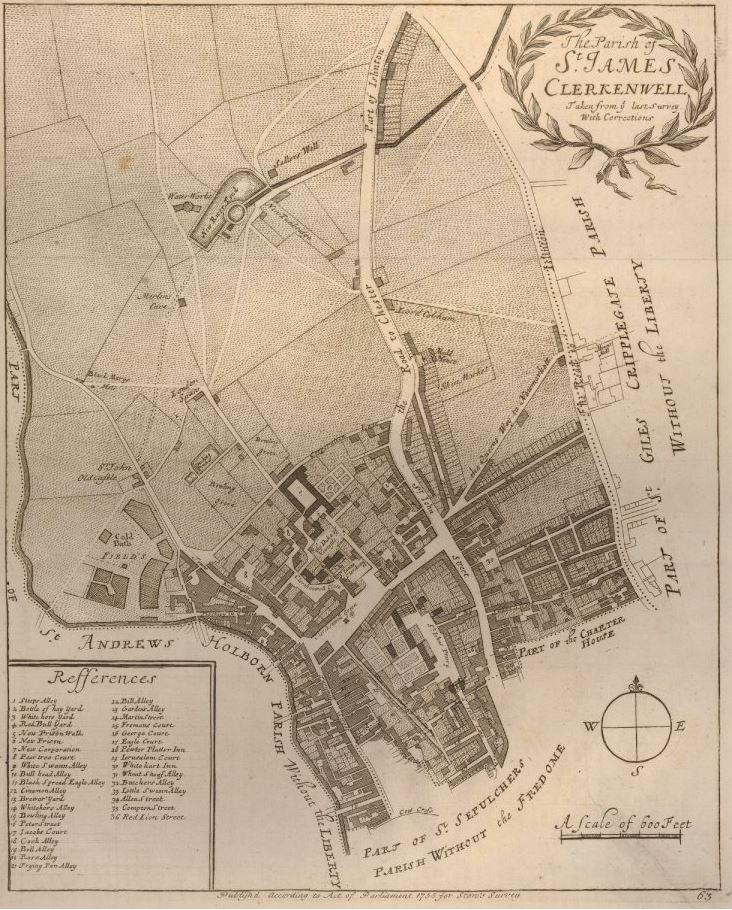

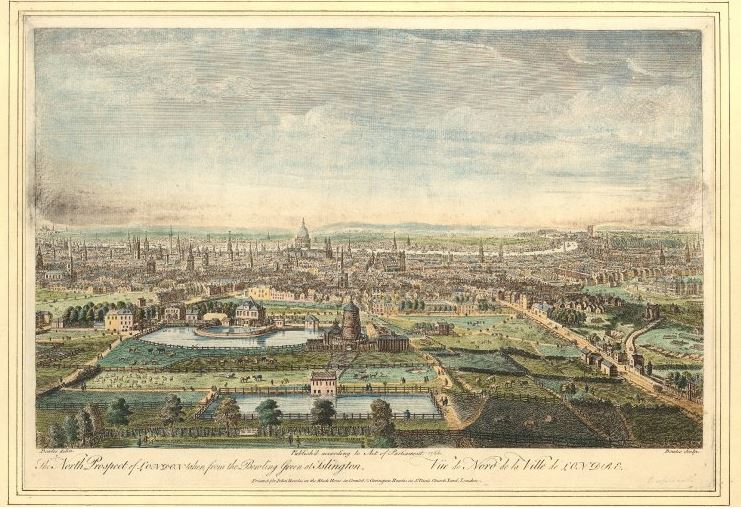

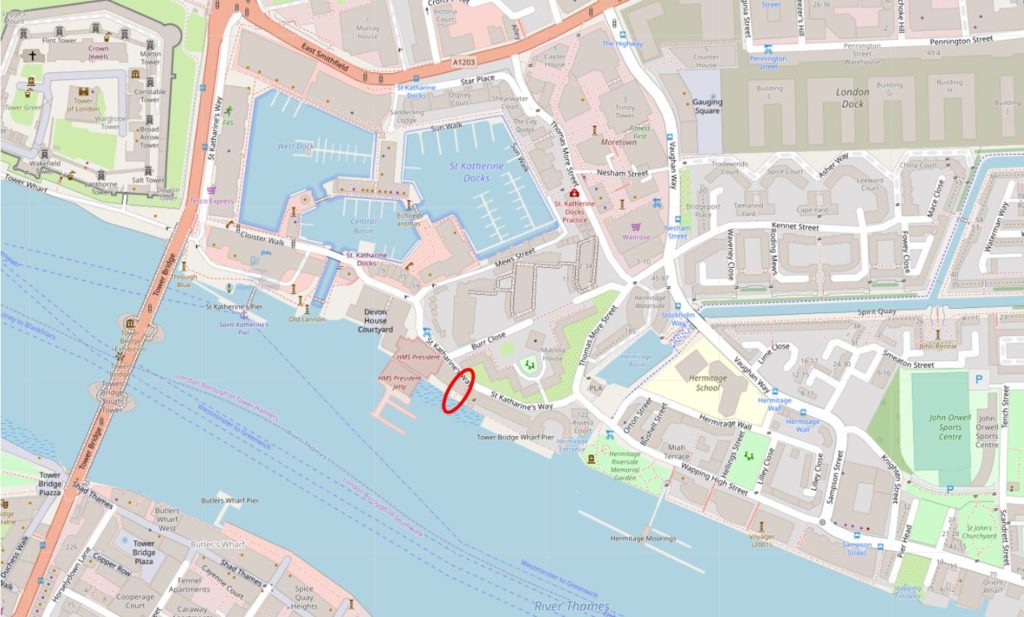

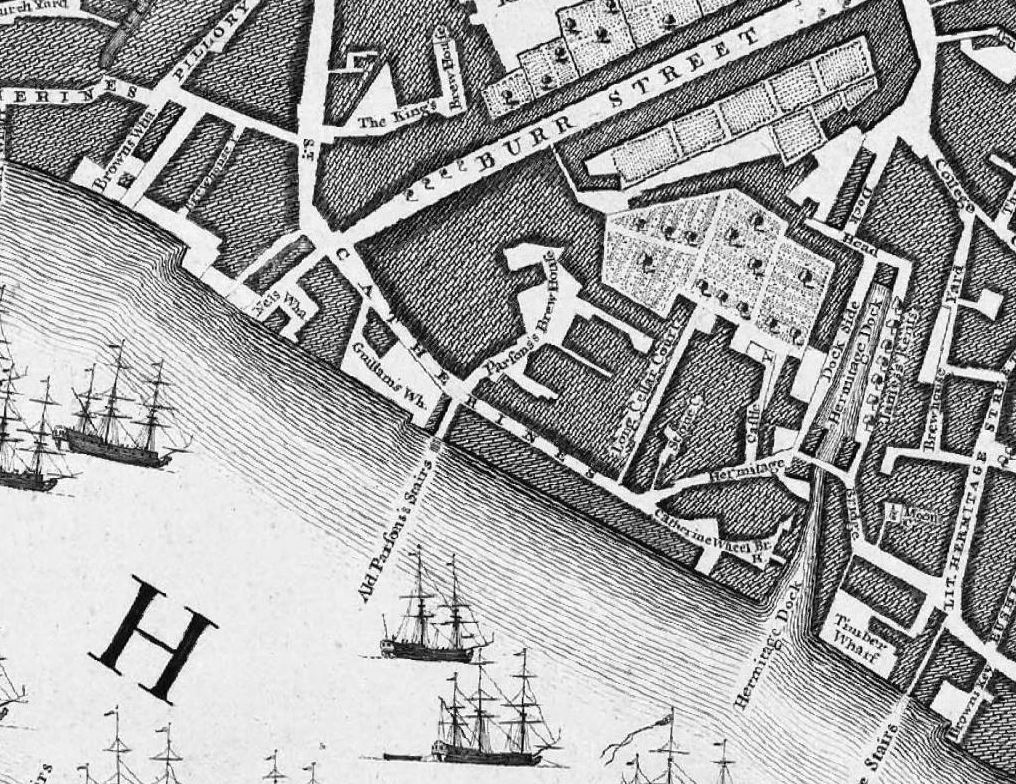

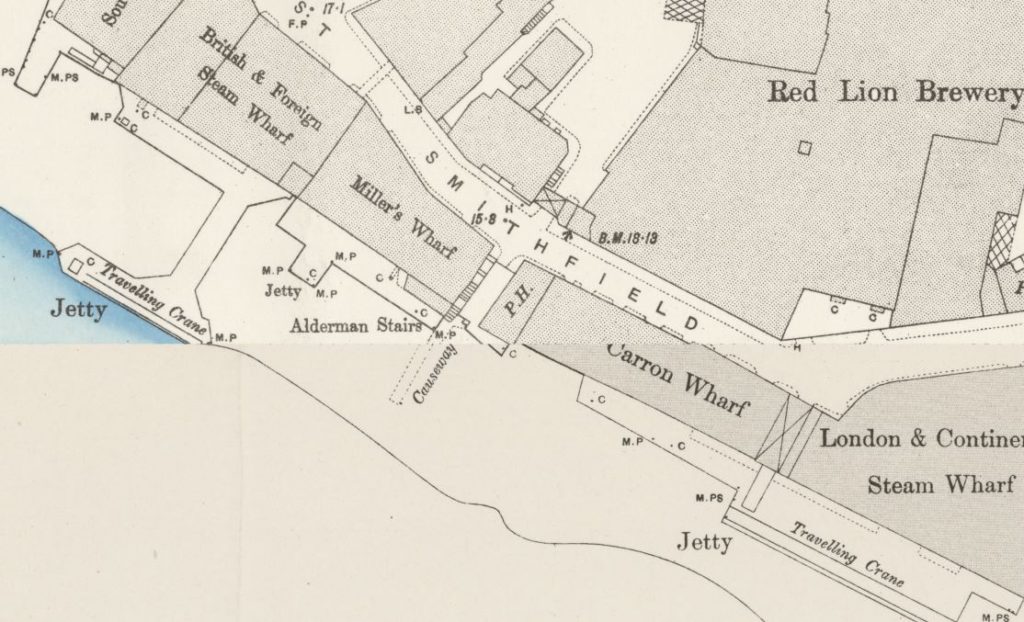

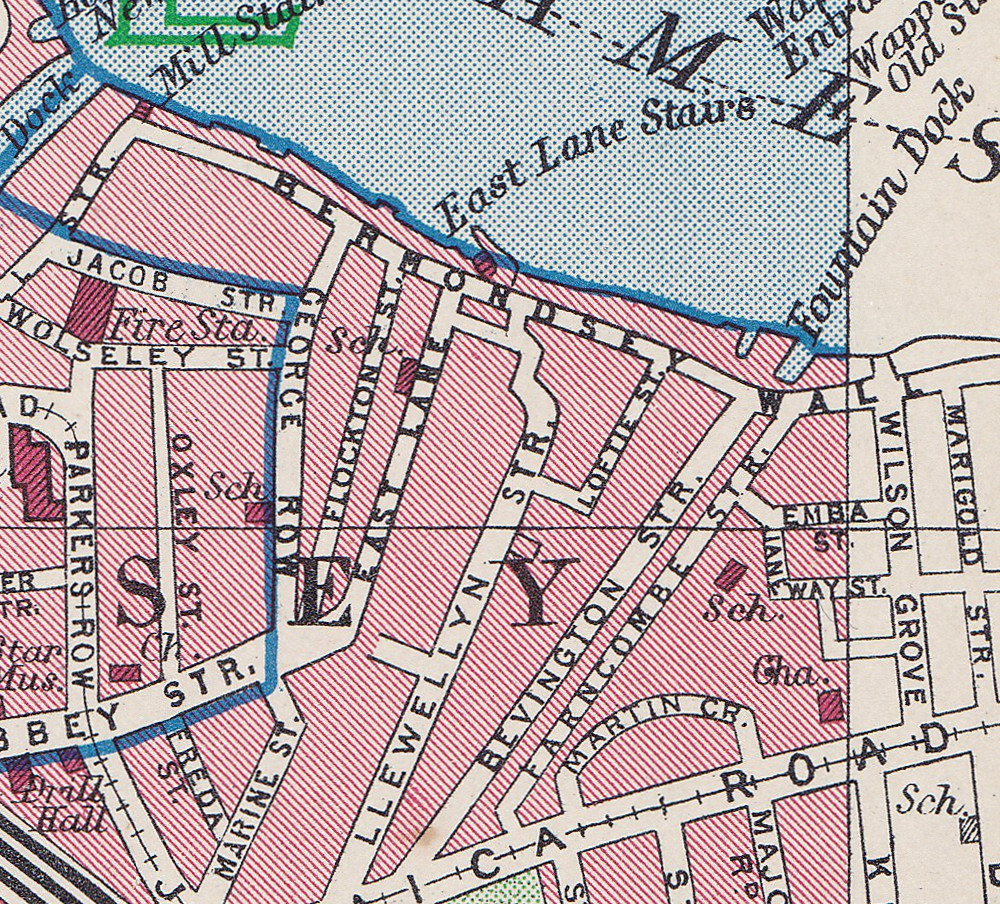

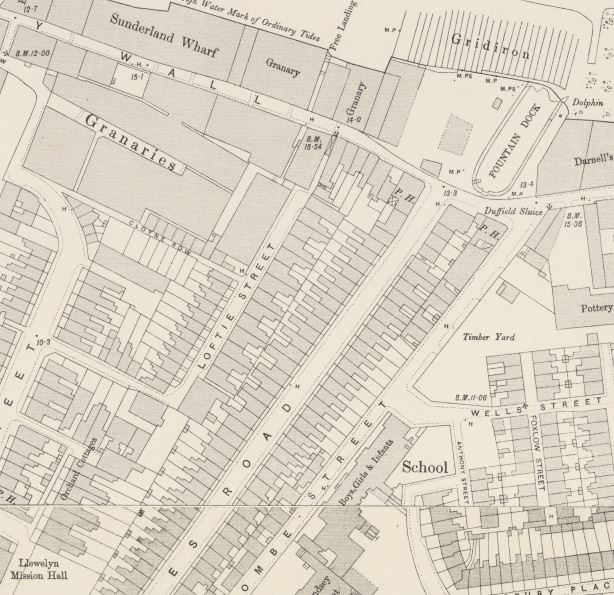

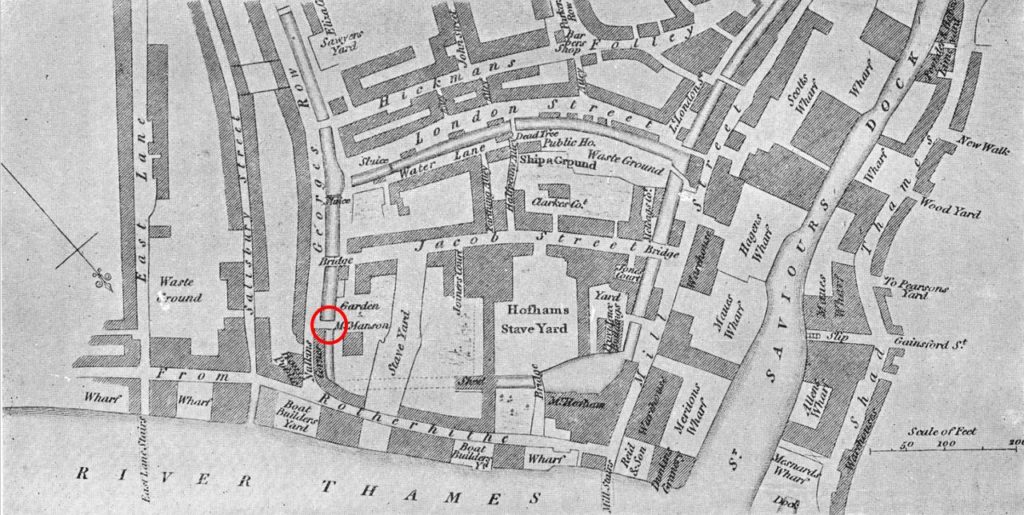

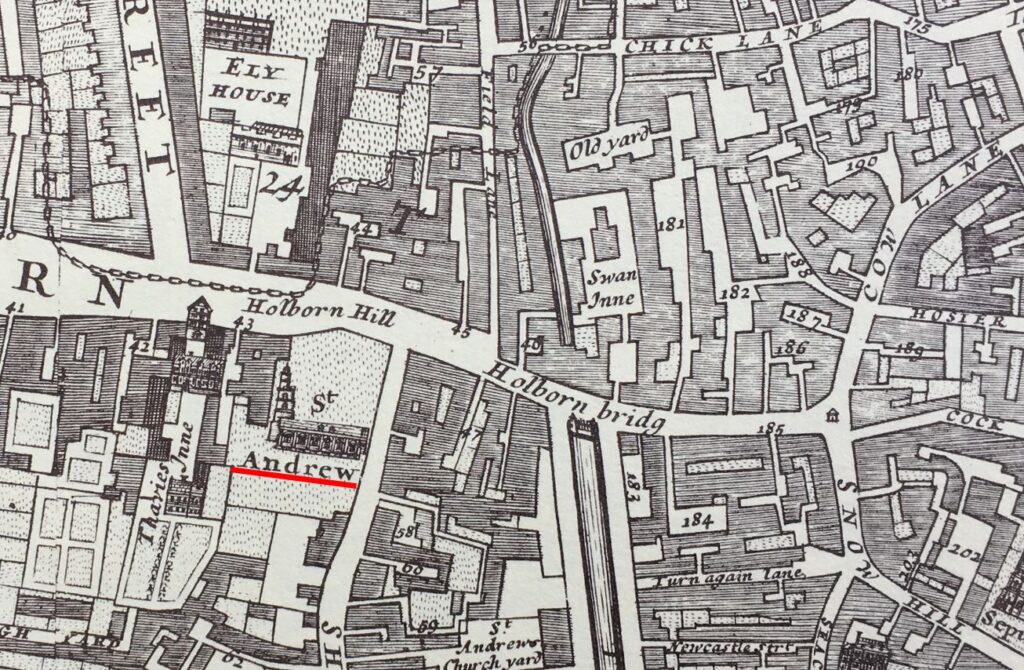

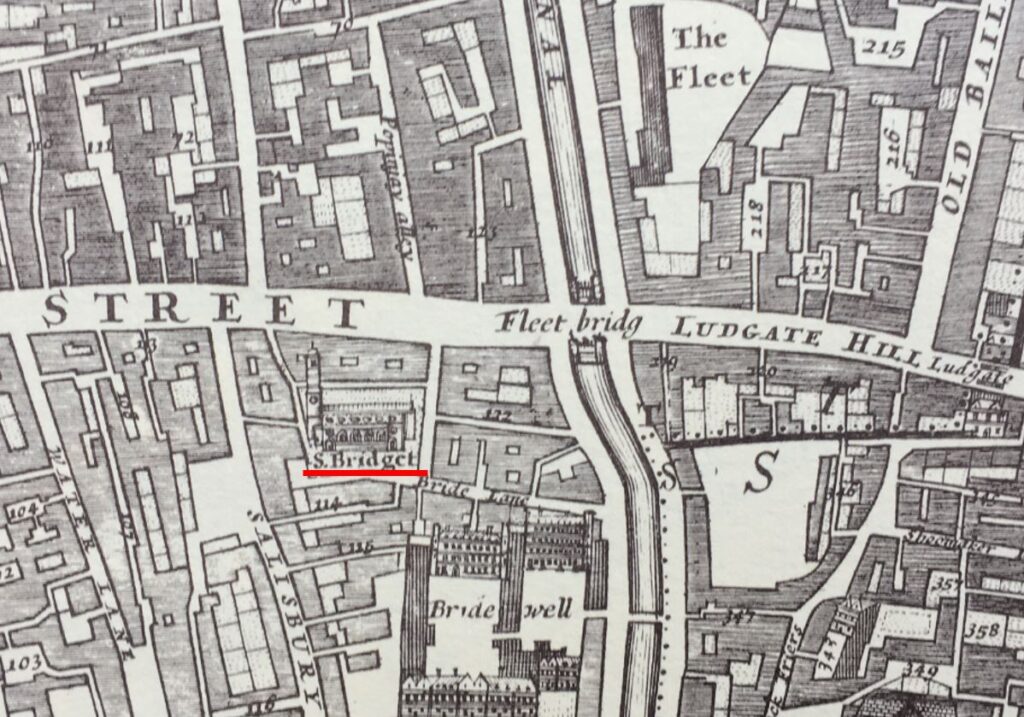

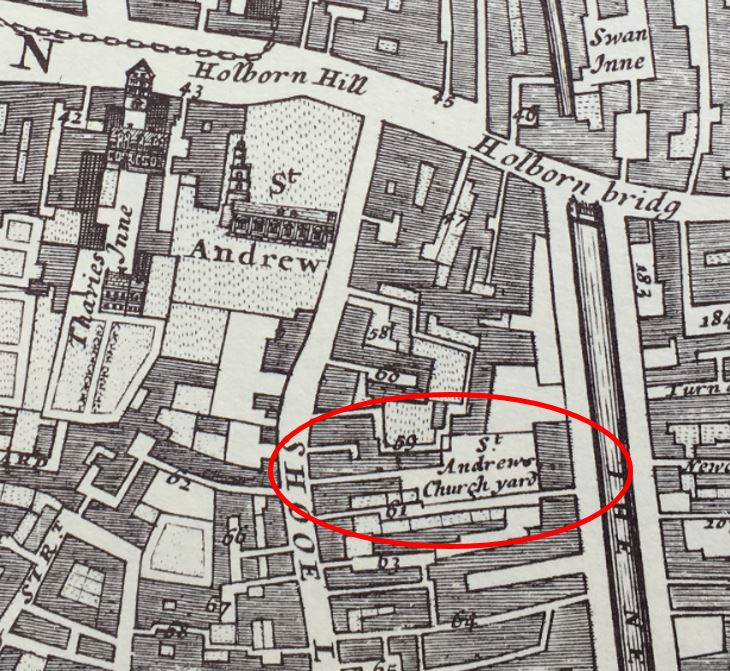

Whilst Holborn Viaduct now carries the street over a large road below, there has long been a bridge here, earlier versions of stone and wood, that carried the road from Holborn towards the City, and we can get an idea of how this looked in the following extract from William Morgan’s map of London from 1682:

I have underlined the location of St. Andrew’s with a red line, and you can see it had a large churchyard up to what was then called Holborn Hill, indicating that this was a hill from the higher ground of Holborn, down to the lower lying River Fleet.

The river can be seen to the right of the church, with Holborn Bridge spanning the river. In the late 17th century, the wide channel of the Fleet down to the Thames became a smaller river running north, although by this time, and with all the surrounding building, it was more an open sewer than a river.

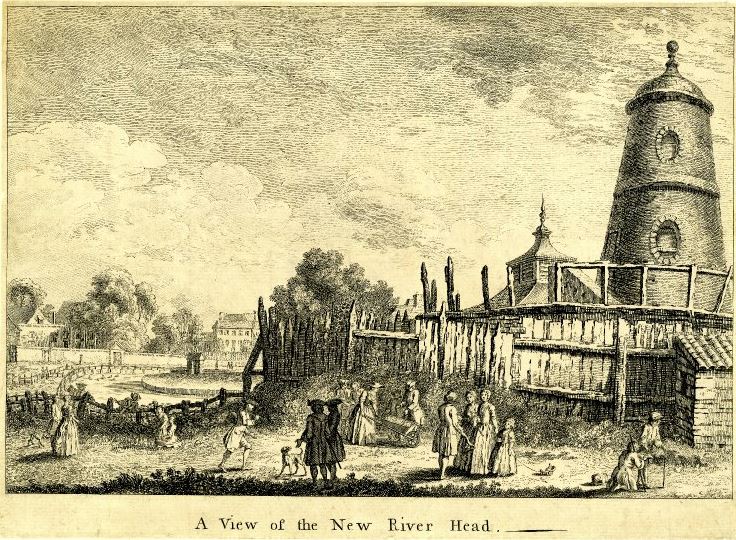

We can get an idea of the gradient of Holborn Hill from the following two prints.

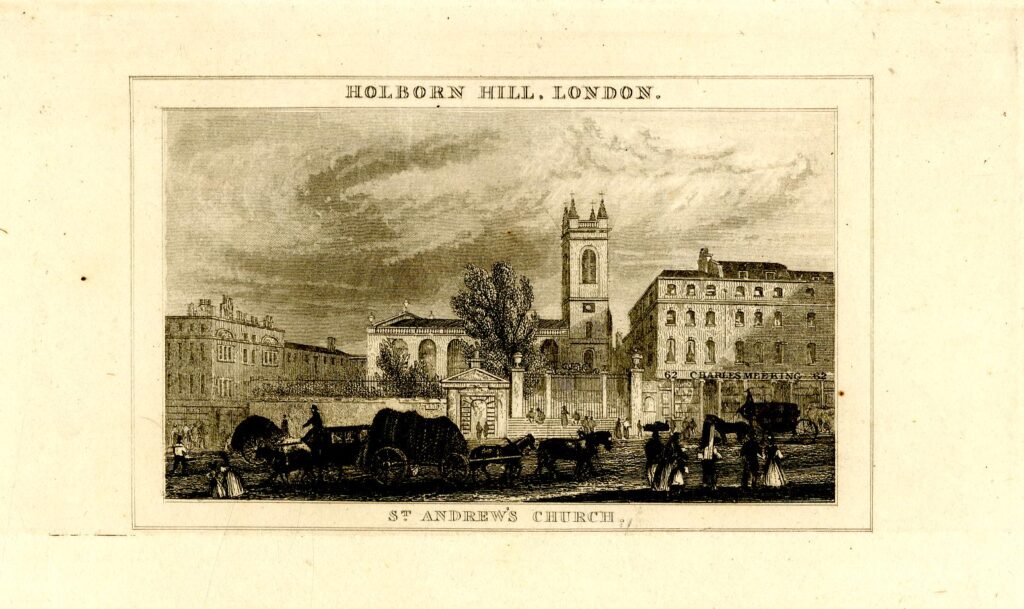

In the first, from the early 1800s, we can see the church and the surrounding churchyard, was originally higher than the street, and you can see the slope of the street outside the church as it heads down towards where the Fleet was once located:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

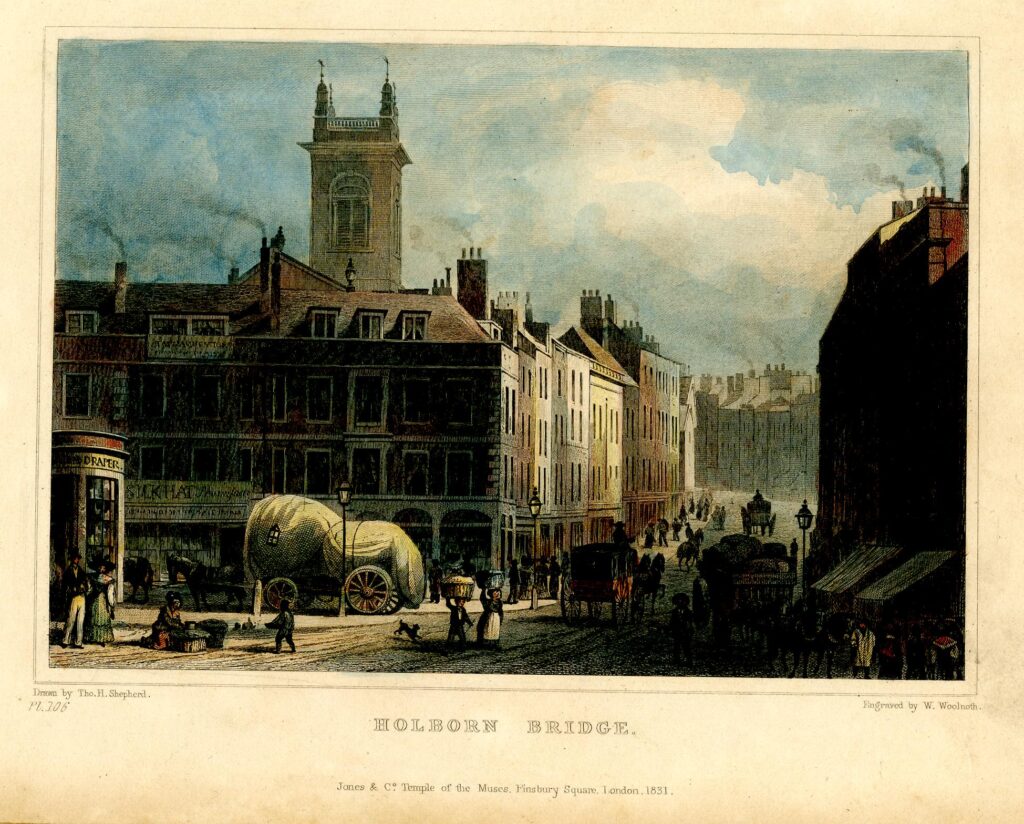

In the second print (from 1831), we are looking across Holborn Bridge (which was roughly at the level of Farringdon Street today), up Holborn Hill, with the tower of St. Andrew on the left:

© The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The above two prints show just how significant the impact of the 19th century Holborn Viaduct was on the area, and in the above print, we can imagine the River Fleet flowing in the foreground, marshy land on either side, then a hill rising up to the church – it would have been in a very prominent position.

St. Andrew occupies a place that has been the site of a religious building for very many centuries. The church we see today is just the latest version of the church.

The first written records of a church on the site date back to the year 959, when a charter of Westminster Abbey refers to an “old wooden church”’ on the hill above the River Fleet.

There was probably a church on the site for some years before the first written record, and we can imagine the scene with a small wooden church sitting on the high ground at the top of a hill from where the land runs steeply down to the River Fleet. A river that would have been wider prior to the buildings shown in the 1682 map, and with marshy banks.

So if you were heading towards the City, St. Andrew’s would have been just before the road descended down a hill to the Fleet, and if you were leaving the City, as you walked up the hill from the Fleet, you would come to St. Andrew’s.

Perhaps if you were entering or leaving the City, crossing the boundary of the Fleet, you would have wanted to pray, perhaps to ask for protection on the next stage of your journey.

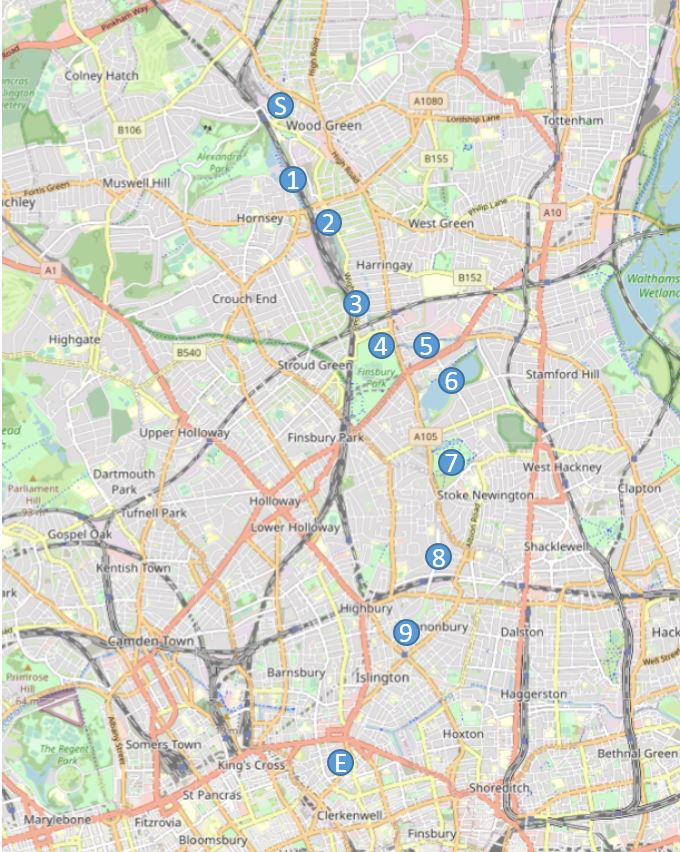

Despite the amount of building across London over very many centuries, we can still see churches at what were major boundaries between the original City of London, and the rest of the city and the wider country. Churches are one of the few fixed points in the City’s landscape that have not moved for often over one thousand years.

We can use Morgan’s 1682 map for a quick tour of these boundaries. Just to the south of St. Andrew is another crossing over the River Fleet, where Fleet Street crossed the river up to Ludgate Hill, and just to the west of the Fleet, the same distance from the river as St. Andrew, we find what was St. Bridget, now St. Bride’s, which does have Roman and early mediaeval features in the Crypt, hinting at the age of the site :

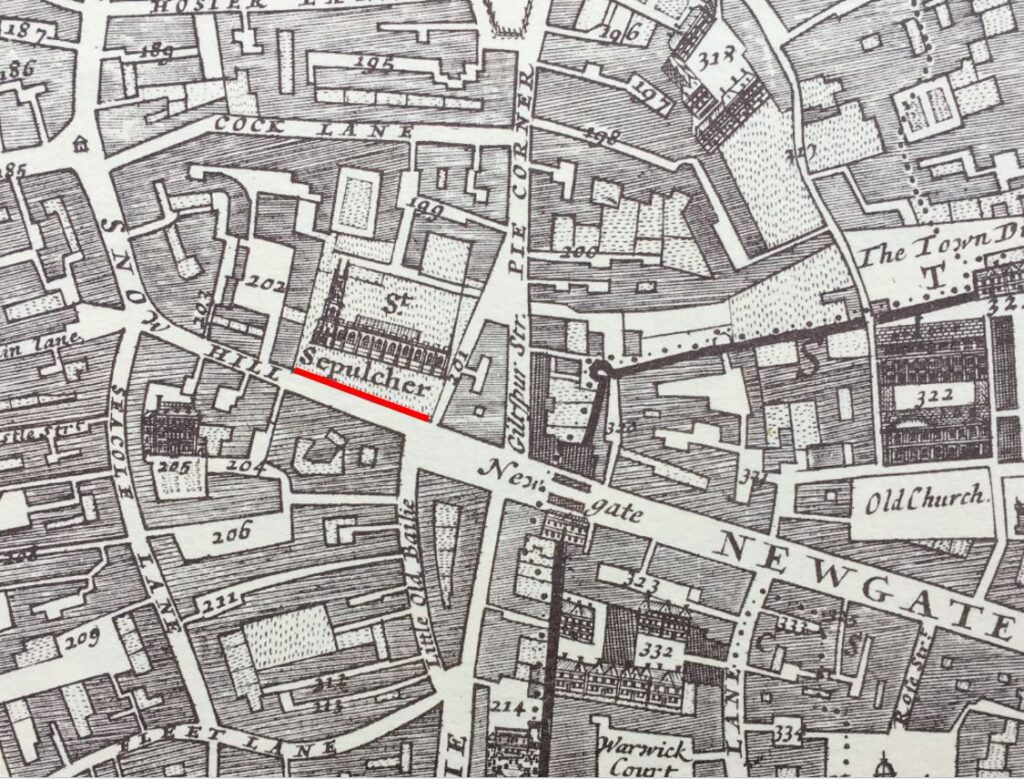

Headimg back north, and just to the west of the entrance to the City through Newgate, we find St. Sepulcher:

We then come to Aldersgate, and just outside the gate we find St. Botolphs (there are three St. Botolphs outside the gates of the City of London. The relevance of the dedication will become clear later in the post):

Following the route of the wall, and next to Cripplegate, we find St. Giles:

On the approach to Bishopsgate, we find St. Botolph, which claims to have been built on the site of an earlier Saxon church:

St. Botolph is the patron saint of travelers, so a church dedicated to the saint would often be found where there are boundaries, or city gates, and another church dedicated to St. Botolph can be found just outside Aldgate, so three with the same dedication, to be found by gates in the old City wall:

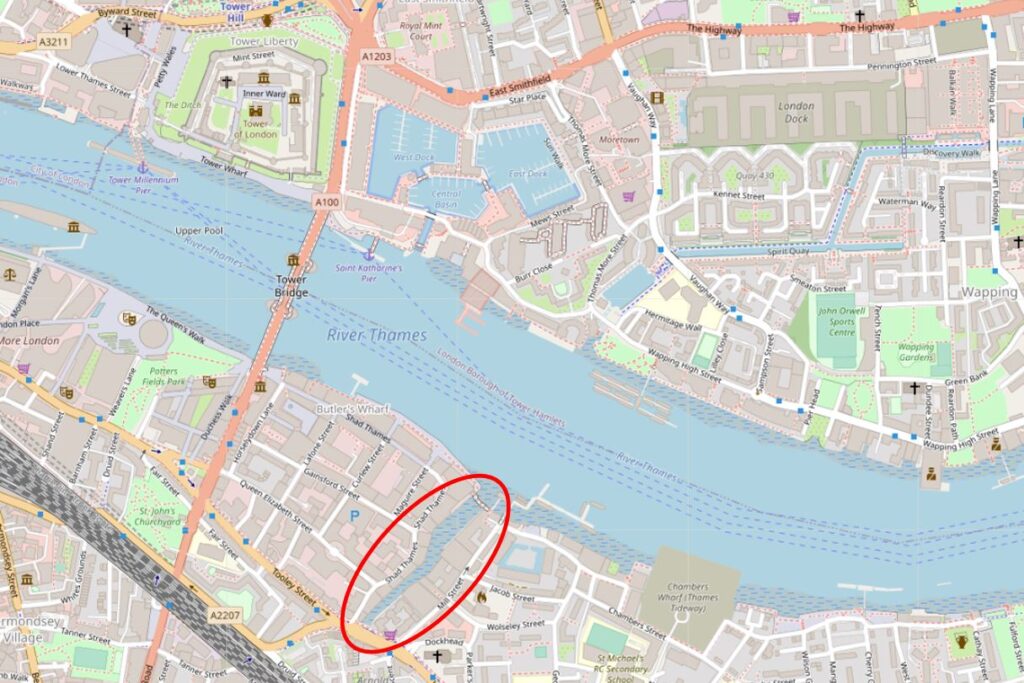

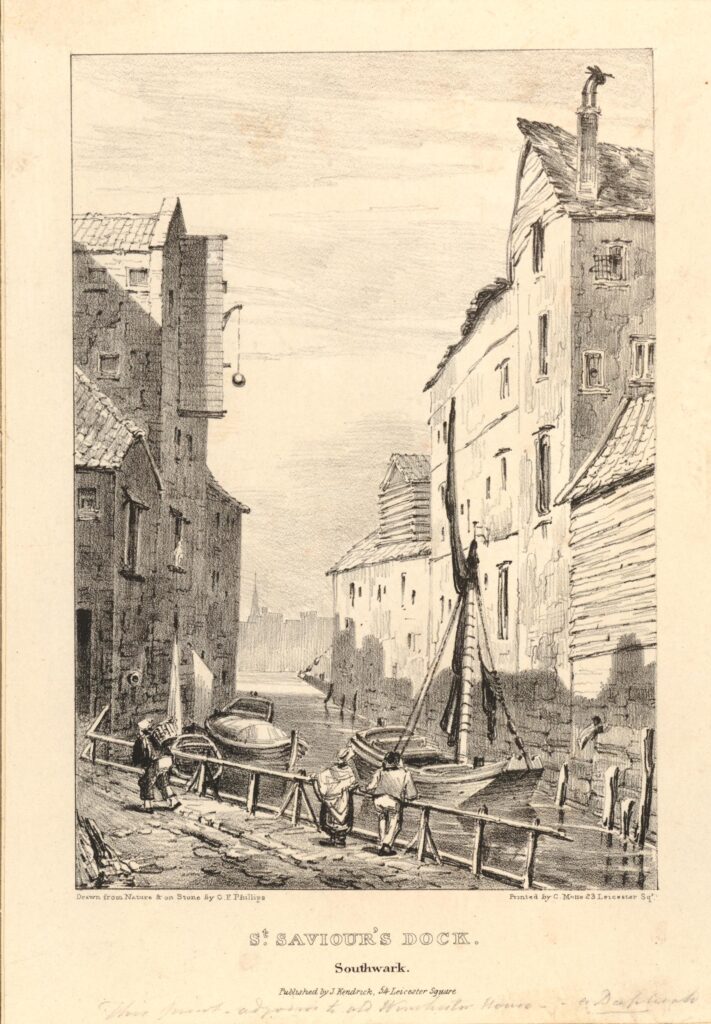

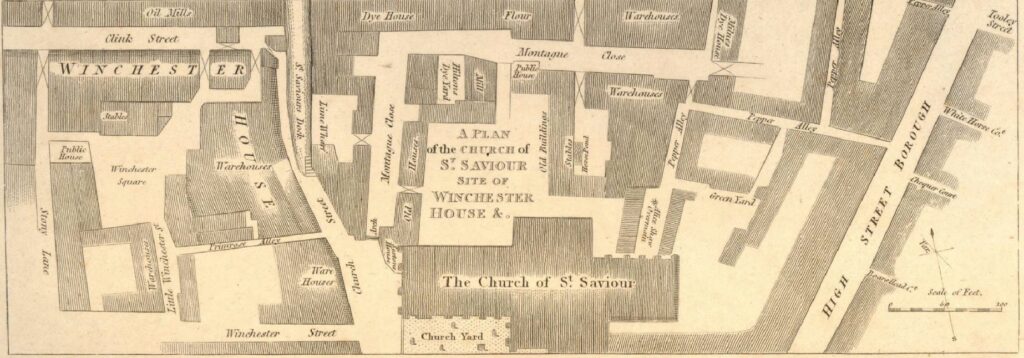

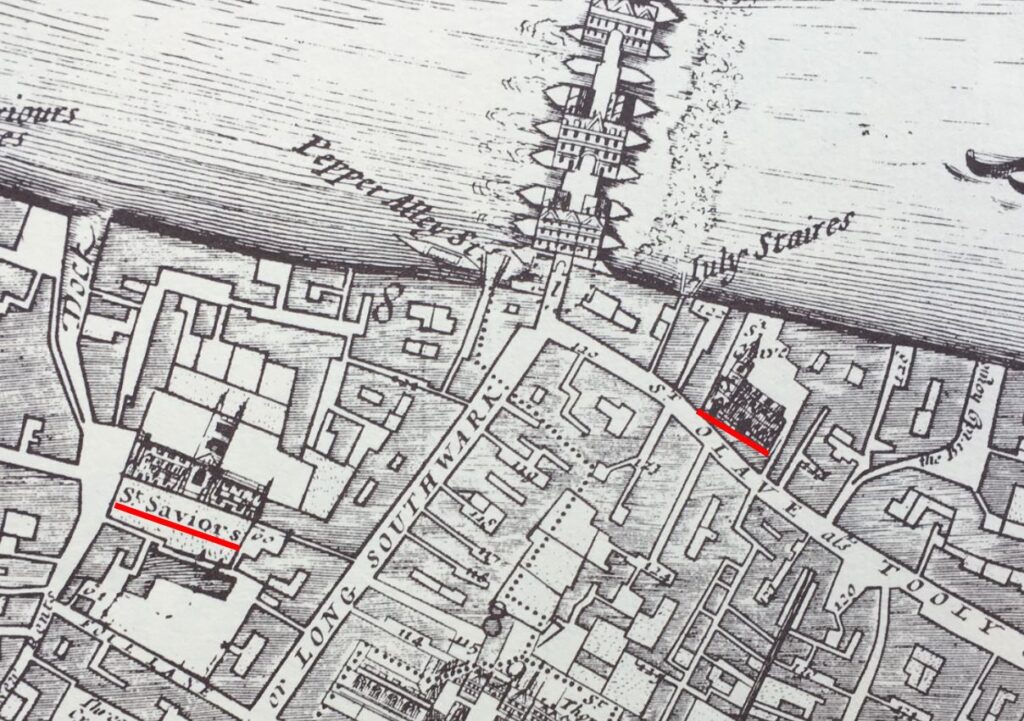

Churches located at major boundaries, crossings, entry and exit points can be found south of the river, and in the 1682 map, close to the southern end of London Bridge, we find two churches, St. Olave’s on the right, and St. Savior’s, now Southwark Cathedral on the left:

There is no church just outside the old Moorgate. I suspect that this may have been due to the marshy nature of the fields outside this gate in early centuries, a moor which gave its name to the area we know today, and which was only drained in the 16th century.

So a church close to a gate into the City of London, or where you would have had to have crossed either the Thames or the Fleet is a feature we can still see today, although the gates or crossing points they marked (with the exception of the Thames) are long gone.

Now let’s walk back to the church, and to get an idea what the hill was like up from the River Fleet in the 18th century, this report from the 11th of February, 1743 gives an indication:

“It is hoped proper Care will be immediately taken to destroy this Gang of Thieves; who to the Number of 20 and upwards assemble every Night, and plant themselves on each Side of the Way, from St. Andrew’s Church to Holborn Bridge, commit all kind of Villainies, and make that Passage the most dangerous of any in the Town”.

You probably would have wanted to nip into St. Andrew for a quick prayer before risking the “Gang of Thieves” waiting for you as you walked down Holborn Hill.

No such dangers today, and as we walk towards the entrance to the church, there are two figures on either side:

The figures are not in their original location, they came from St Andrew’s Parochial School for children of the poor dating from the 1720s. The school was based in a Chapel of Ease built in Hatton Garden in the 1670s. The building is still there today, and I will return to it in a future post.

The interior of the church has white upper walls with gold decoration, and wood paneling around the columns and side walls on the ground floor, which lead up to a gallery with tiered seating on either side:

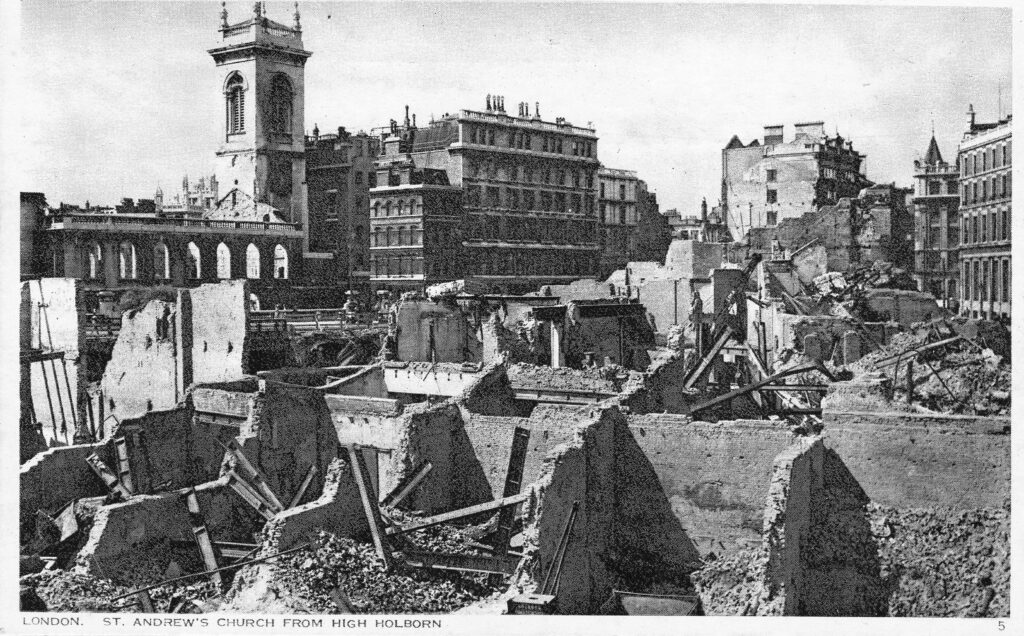

The interior of the church looks very new, and was the result of a rebuild by the architects Seely and Paget between 1960 and 1961 to repair the very considerable wartime damage to the church.

The church featured in one of a series of postcards called London under Fire, showing damage to the city. In the postcard, the church can be seen on the left. the roof gone and the interior gutted. The side walls and tower surviving. The result of an incendiary bomb falling on the church:

The full series of London under Fire can be found in this post.

The church we see today, and the walls and tower in the above photo are from Christopher Wren’s rebuild of the church between 1684 and 1690. The previous church escaped any damage from the Great Fire, however it was a 15th century rebuild of an earlier medieval church, and was in need of significant repair.

Looking up to one of the galleries that run either side of the church:

Today, St. Andrew is a non-parochial Guild Church, meaning that the church serves the local working population rather than any resident population, so you will not find a Sunday service held at the church.

The pulpit:

The interior of the church looking back towards the main entrance and the organ:

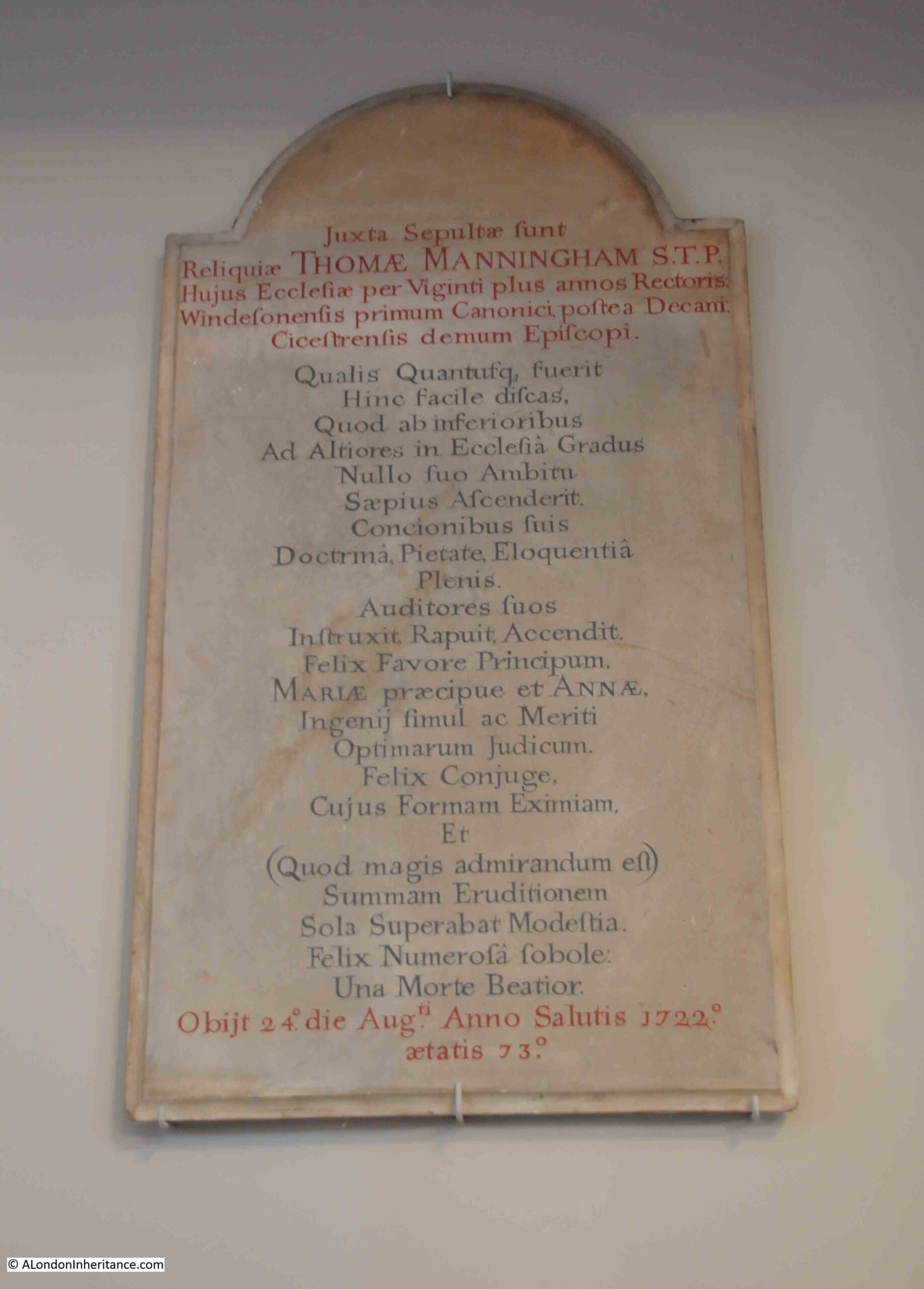

There are very few memorials in the church, perhaps because of the destruction of the interior during the last war. There are a few on the wall, on either side of the main entrance, including one that dates from 1722:

St. Andrew, Holborn does have a wide range of associations with people and events over the years.

In 1799, Marc Brunel, the father of Isambard Kingdom, was married in the church, and in 1817 Benjamin Disraeli, a future Prime Minister, was christened in the church at the age of 12.

Another story connects the church with the founding of the Royal Free Hospital. The story concerns a local surgeon, William Marsden, who found a young girl dying from exposure in the churchyard on a winter’s night in 1827.

Marsden tried to get the girl into a hospital, however none would accept her, and she went on to die. Hospitals at the time usually required a letter of recommendation from a subscriber to the hospital

Marsden was so appalled by the attitude of these hospitals, and the lack of any care for those who had no ability to pay, that he decided to open a new hospital for those who could not pay or provide a letter of recommendation..

Marsden had the support of the Cordwainers Company, and in April 1828 he opened the Royal Free Hospital in a small house in Greville Street, Hatton Garden (originally just the Free Hospital, with Royal added not long after through the patronage of the Duchess of Kent and Princess Victoria).

I could not find any reference from the time to the founding story of the discovery of the girl in the churchyard, however reports of annual general meetings of the hospital do confirm the aims of providing free care for those who could not afford to pay, and who could not get a letter of recommendation from a subscriber. For example, from the record of the 1837 anniversary dinner:

“This institution has been established to afford immediate assistance to all applicants, but more particularly to meet the wants of the poor and diseased, whose wretched situation and circumstances render them, in most instances, unable to procure the recommendations required to obtain admission or assistance from the hospitals and dispensaries of the metropolis, and from which this institution differs in these important facts – that its doors are always open to the poor and afflicted, without any passport save their own infirmities.

No ticket or recommendation from a subscriber is necessary; poverty and disease are alone the wretched qualifications which entitle them to the benefit the charity is capable of affording.”

The Royal Free Hospital is now in Pond Street, Hampstead, and William Marsden would also found, in 1851, the Brompton Cancer Hospital, which would become the Royal Marsden Hospital.

St. Andrew’s has another connection with someone who would try and help the poor of the city.

Just inside the main entrance to the church is the tomb of Thomas Coram, the founder of the Foundling Hospital, which started out in a temporary building in Hatton Garden in 1741.

Foundlings were abandoned very young children, or the young children of single mothers or poor parents, who could not afford to bring up their child.

The Foundling Hospital deserves a full post, but in the entrance to St. Andrew’s, we can see Coram’s tomb. He was originally buried on the site of the original Foundling Hospital, but in 1955 his tomb was moved to St. Andrew’s when the hospital buildings in Berkhampsted (the location of the Foundling Hospital after moving from where Coram Fields is today) were demolished:

The font and pulpit from the Foundling Hospital chapel were also moved to St. Andrew’s.

Another survivor from another place at St. Andrew’s is a resurrection stone, showing Christ standing over the dead, as they rise from their coffins preparing for the final day of judgment:

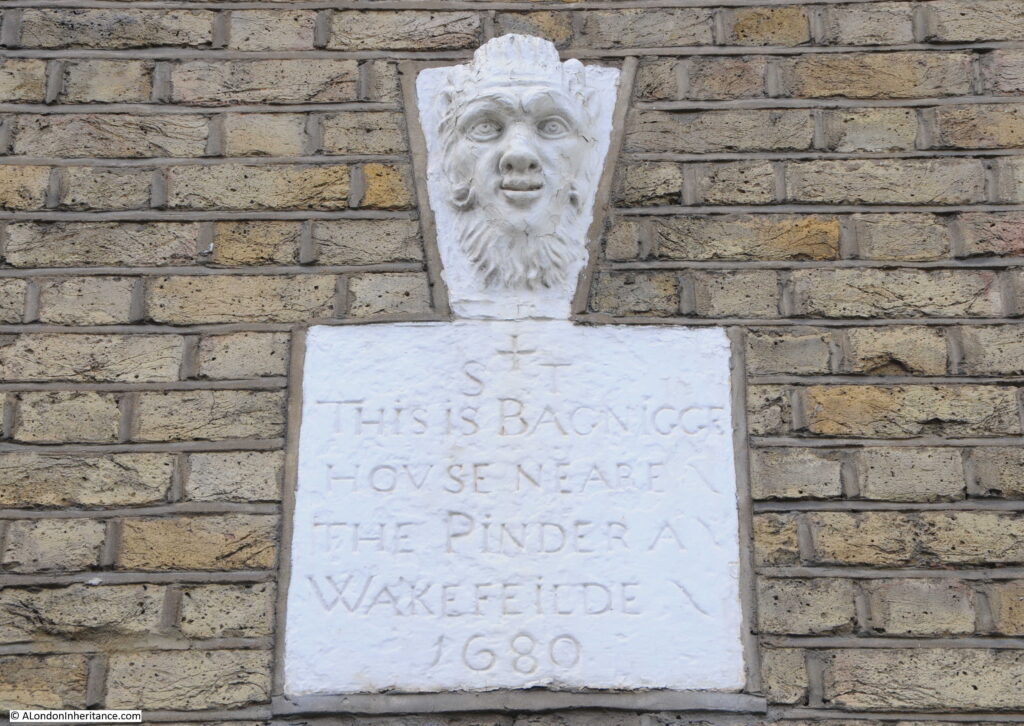

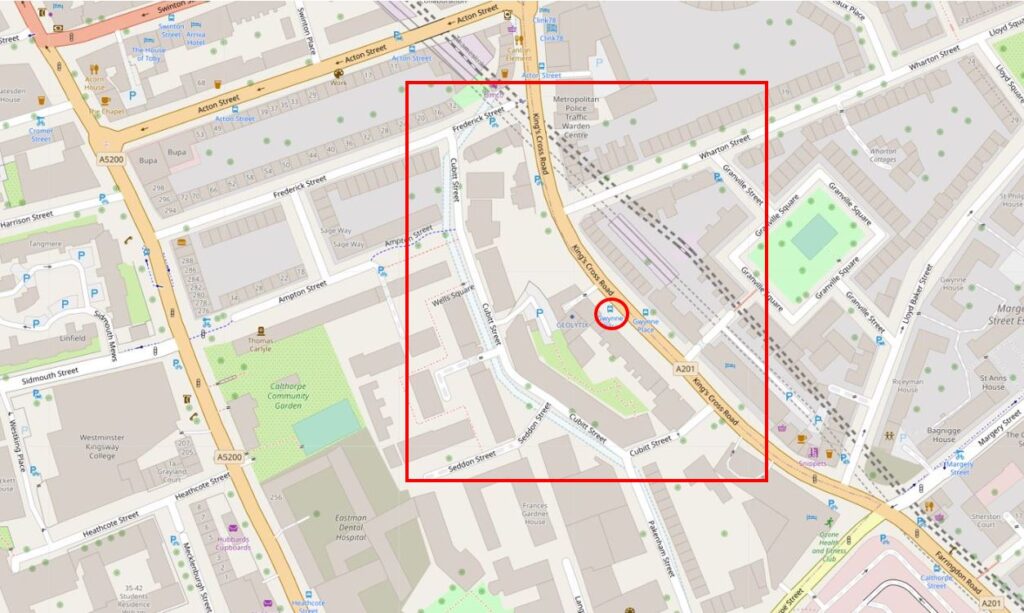

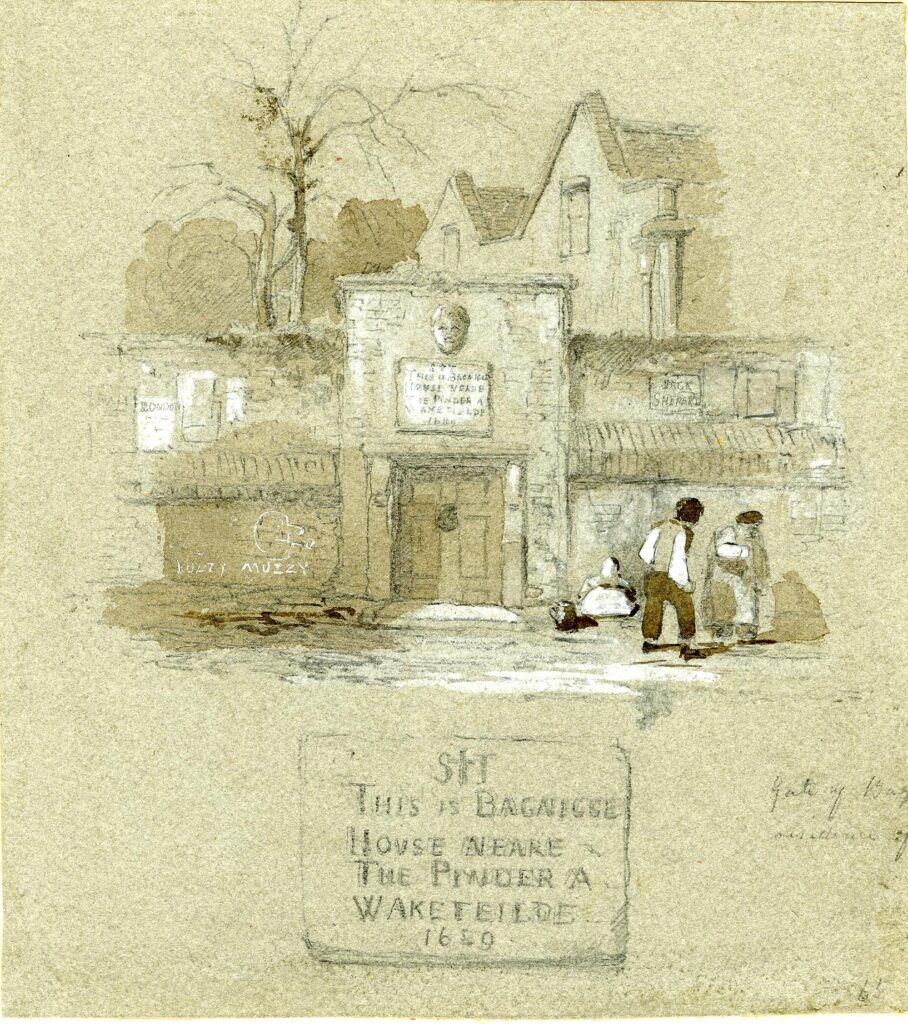

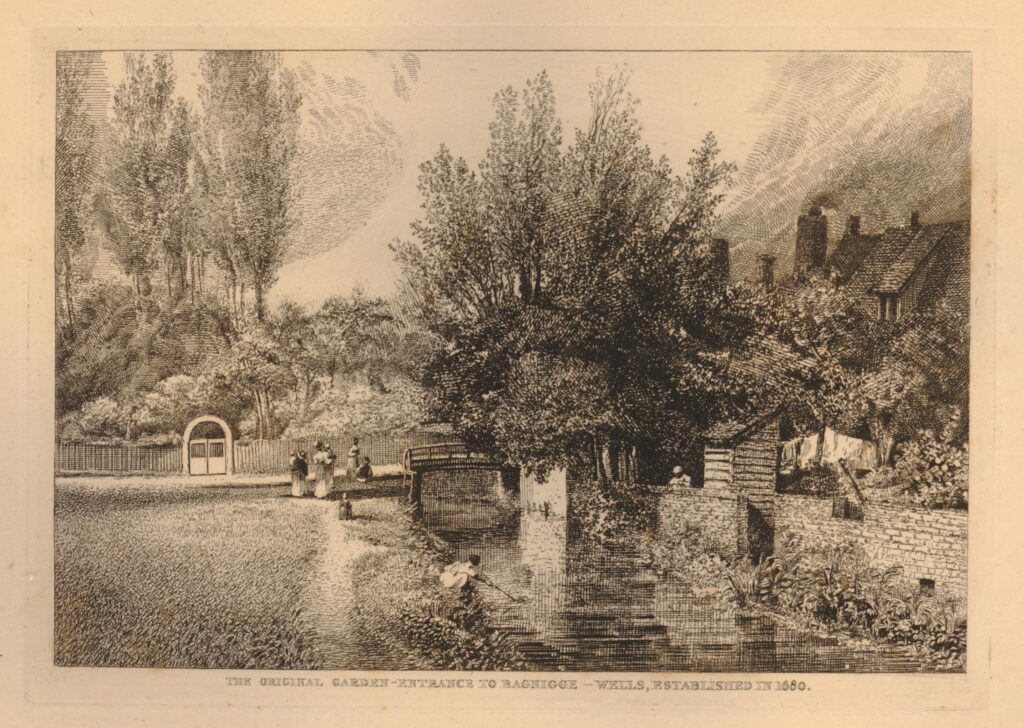

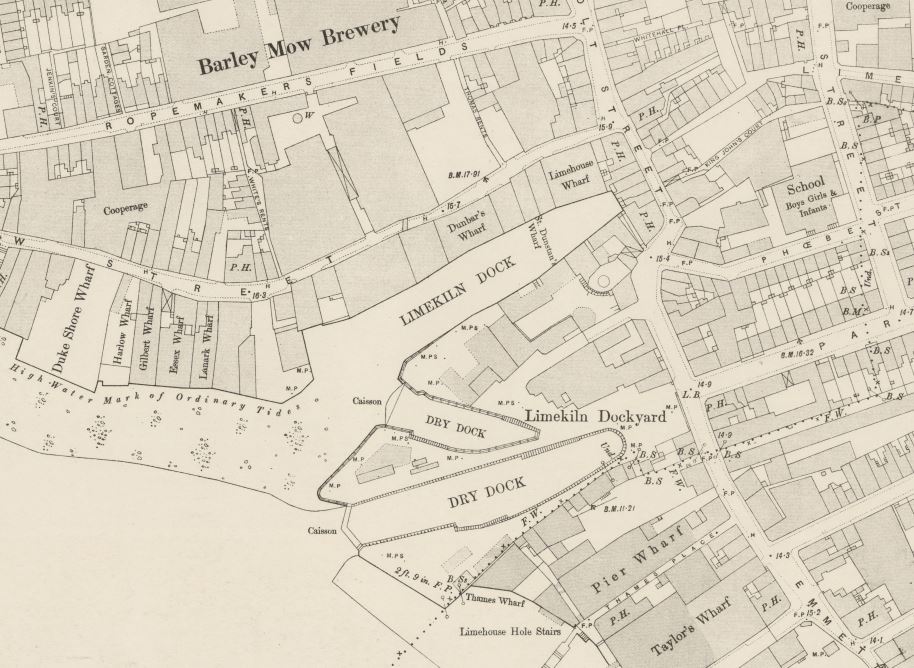

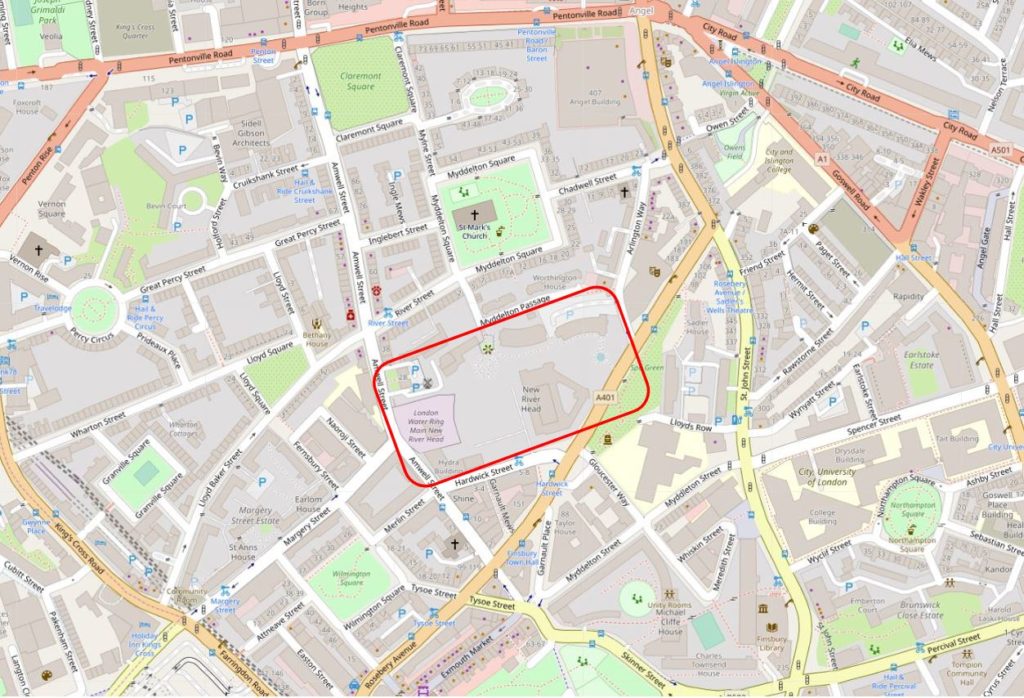

The resurrection stone came from the entrance to a cemetery used by St. Andrew’s for burying the poor, located a short distance from the church with an entrance from Shoe Lane, ringed in the following extract from Morgan’s 1682 map:

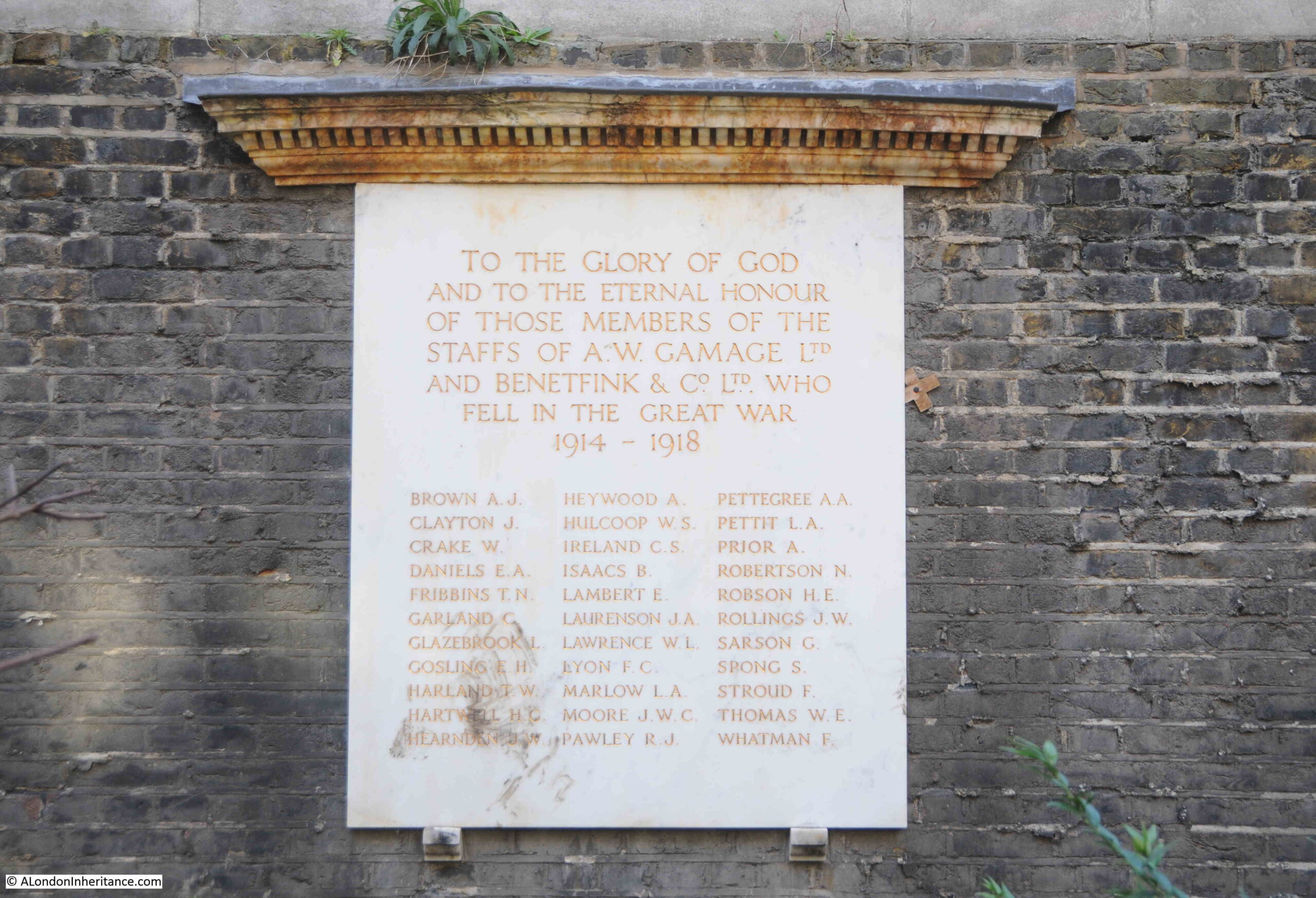

Another survivor, very different, but no less interesting, is the war memorial from the stores of A.W. Gamage and Benetfink & Co:

Not exactly what you would expect to find hidden in a City churchyard. Gamages was a large department store in Holborn and Benetfink were a Cheapside based ironmongers, taken over by A.W. Gamage in 1907.

Gamages closed in March 1972, and the war memorial was moved to St. Andrew’s churchyard.

I have no idea why it is in the churchyard rather than inside the church, however it is good that it remains in Holborn, and is the last trace of the Gamages company and department store to be found in Holborn.

As usual, a quick run through some fascinating history, and St. Andrew, Holborn is an interesting example of how churches were located at important boundary points, boundaries that are not (with the exception of the Thames) visible today.

We cannot get into the minds of mediaeval inhabitants of London, so it is difficult to fully understand the importance of a church at such a location, but given the number of churches through the City, it does show how important religion was, including at places where you were crossing a boundary, entering or leaving the City, crossing the Fleet or the Thames.