I read this week that sales of printed books are rising and that their demise at the hands of the eBook reader is hopefully not going to turn out to be true.

I love printed books. Not just to read, but also as a living record of information added by those who have owned the book. Many of the London books in my collection have annotations along with cuttings from newspapers and magazines over the last 70 years that add to the original text contained within the pages of the book.

The 1975 edition of Dan Cruickshank’s “London: The Art Of Georgian Building” has newspaper articles inserted detailing the destruction and development planned for London’s Georgian buildings during the 1970s, 80s and 90s. The 1923 edition of Historic Streets of London by Lilian and Ashmore Russan has the comment “Rot !!! confused with Battle Bridge N.W.1” against the entry for Battle Bridge Lane in Bermondsey which states that it “Marks the place where the Romans defeated the Iceni, under Queen Boadicea, in the year AD61”

Rather than a one off read, books can therefore be a repository for new information as well as something to challenge and correct.

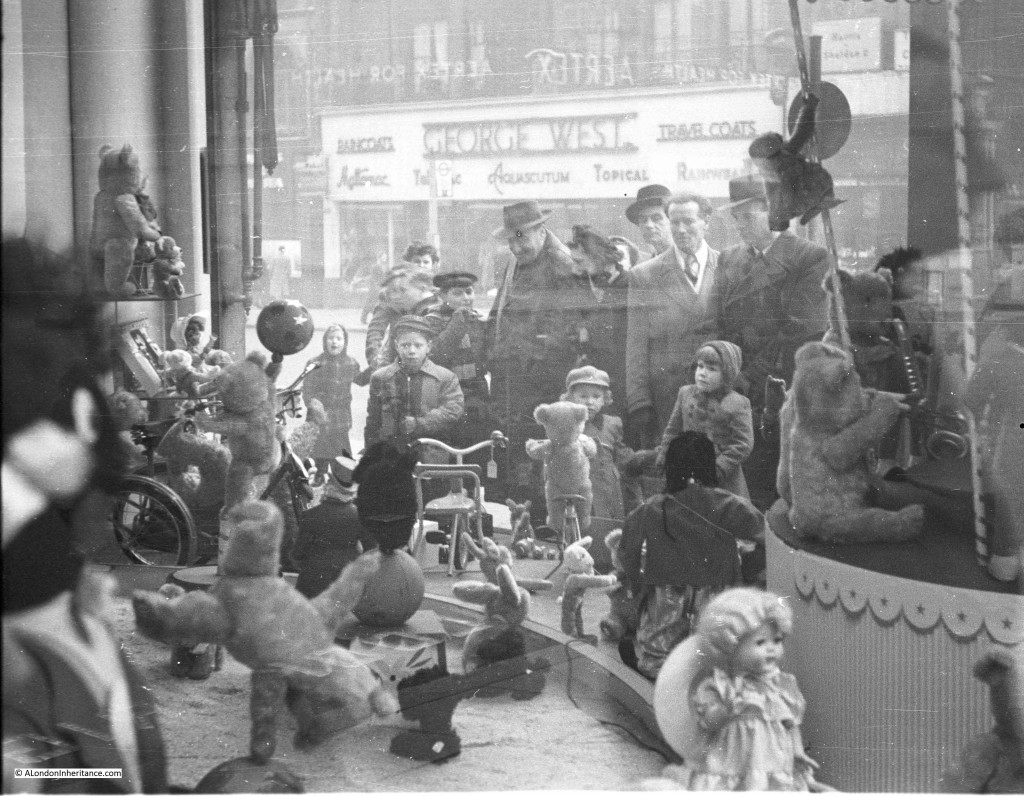

One such book is “Unbidden Guests – A Book of Real Ghosts” by William Oliver Stevens published in 1949. As well as the contents of the book, my copy is also stuffed full of newspaper and magazine articles recounting ghost stories from the last 60 years, and for this week’s post, as we approach the shortest day of the year when darkness falls over London from the late afternoon, here are a few of those articles, a sample from a series printed by the London Evening News in the run up to the Christmas of 1957.

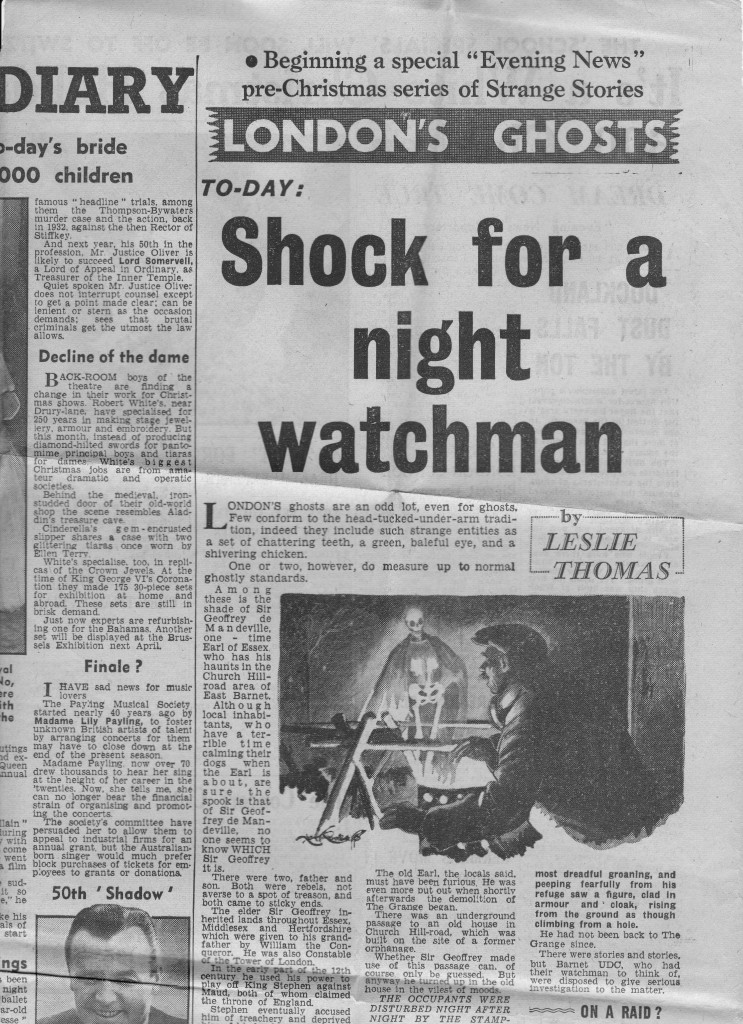

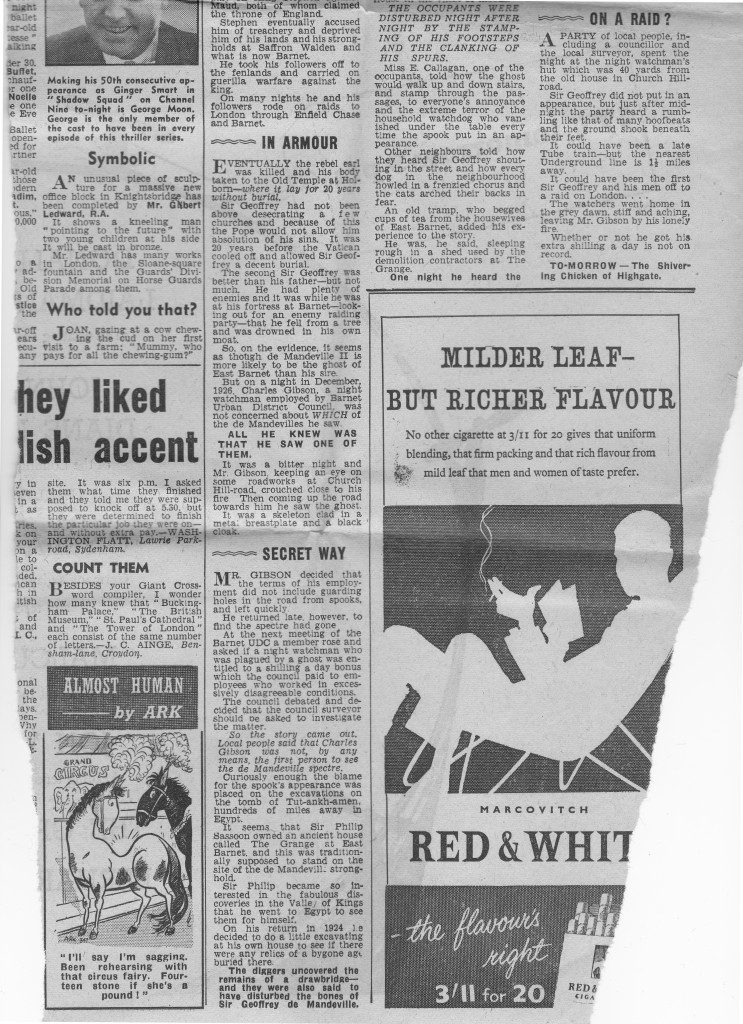

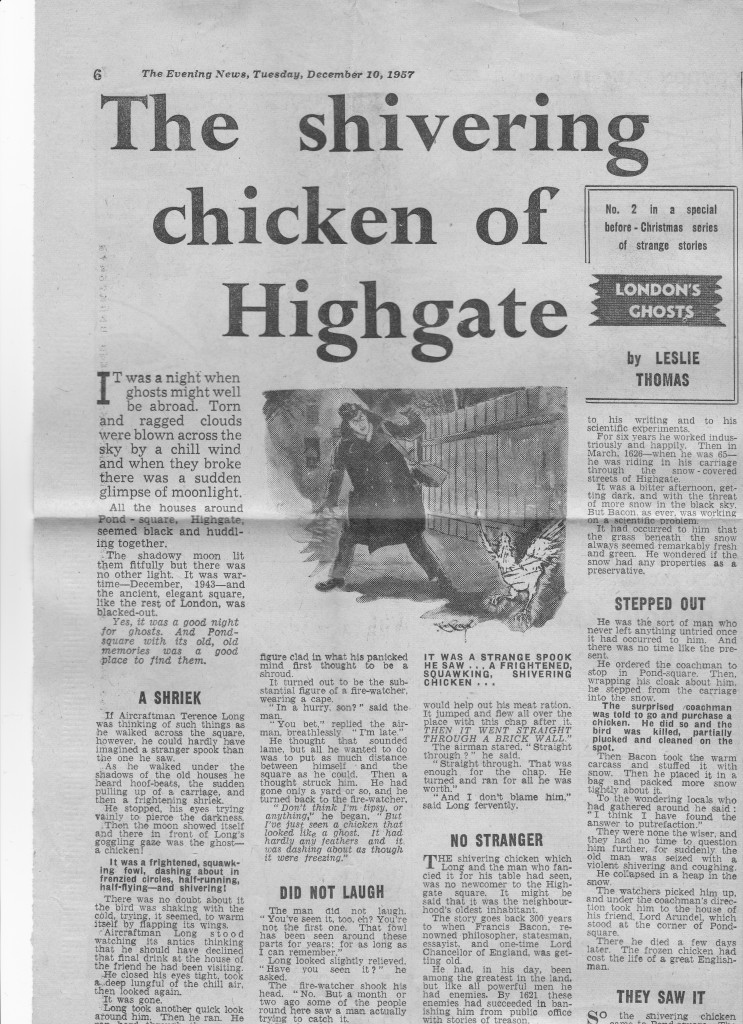

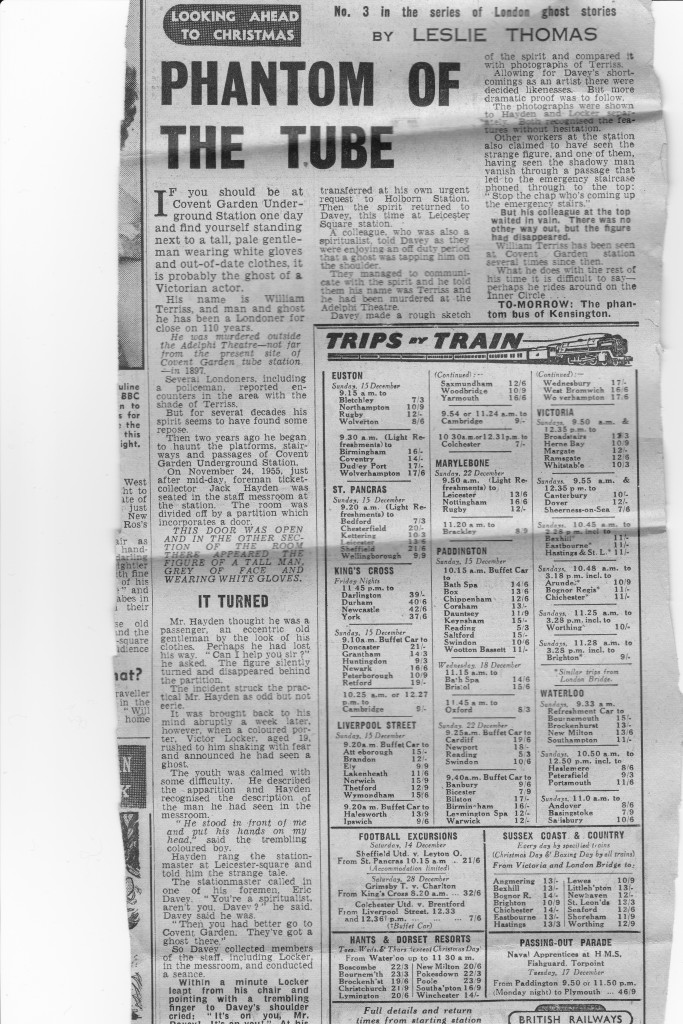

These were written by Leslie Thomas who would later find fame following publication of his book The Virgin Soldiers in 1966. At the time of these articles, he was a feature writer for the London Evening News. He worked for the paper from 1955 to 1966 when the success of The Virgin Soldiers convinced him that he could make a career as an author.

These stories of London Ghosts are written in a suitably dramatic form and most have an illustration of the haunting to draw in the reader. I like to imagine Londoners reading these articles as they make their way home in the evening on a cold, dark and foggy December night when anything would seem possible.

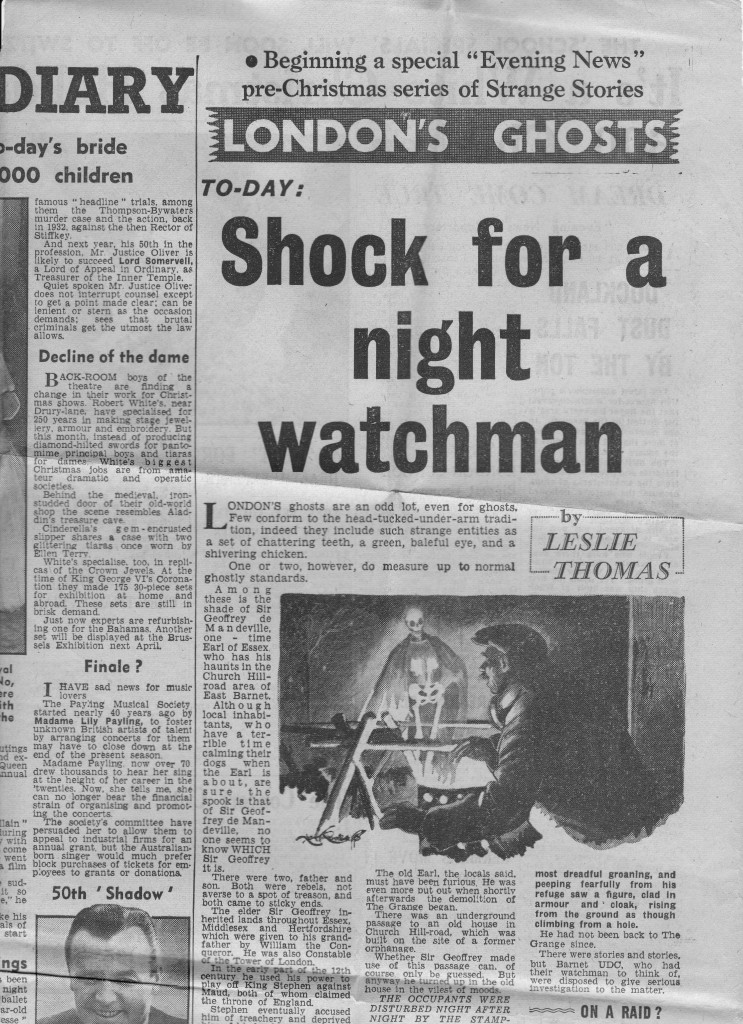

The first story is from 1926 when a Mr Gibson, a night watchman guarding roadwork’s in Church Hill Road, Barnet saw the ghost of Sir Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex as a skeleton clad in a metal breast plate and black cape coming up the road towards him.

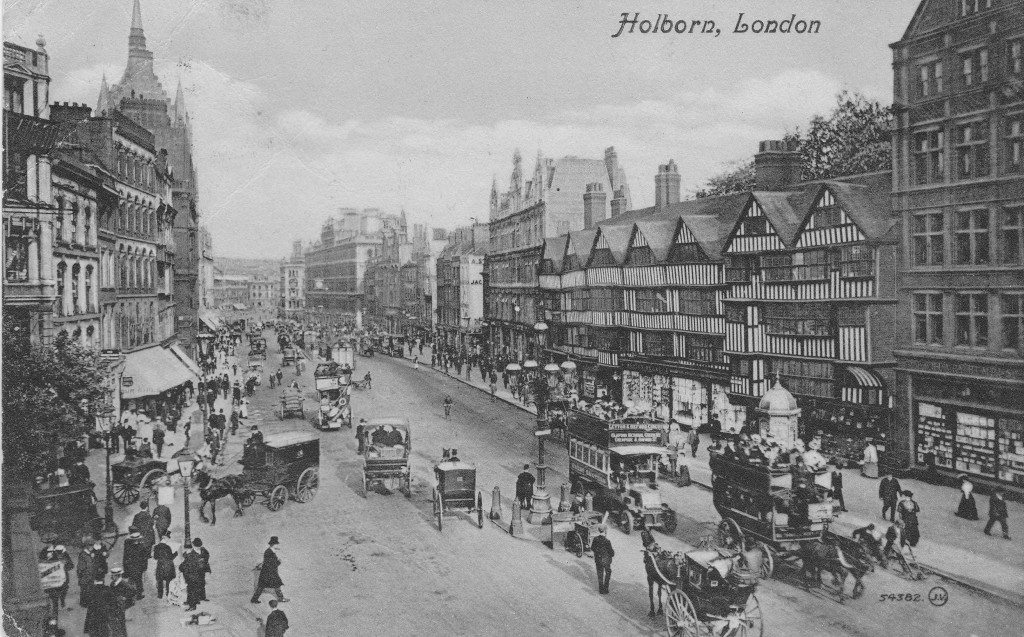

There were two Sir Geoffrey’s in the 12th century, the elder inheriting lands in Essex, Middlesex and Hertfordshire. His political scheming resulted in him being accused of being a traitor. Sir Geoffrey and his followers carried out guerrilla warfare, travelling on roads to London through Enfield Chase and Barnet. On his eventual death his body lay in Old Temple, Holborn for 20 years without burial. The second Sir Geoffrey had a fortress at Barnet and apparently fell from a tree and drowned in his own moat.

An old house in East Barnet called the Grange was allegedly built on the de Mandeville’s old fortress and when excavations disturbed the foundations of the old building the haunting started, including the stamping of footsteps and clanking of spurs, along with sightings as witnessed by the poor night-watchman.

The Evening News story concludes with a party of local people including a councillor spending the night at the night-watchman’s hut in Church Hill Road. Although nothing was seen, just after midnight the party heard a rumbling like that of many hoof beats and the ground shook.

A chilling tale from Barnet and I doubt the night watchman ever returned if the illustration is an accurate portrayal of his night on Church Hill Road.

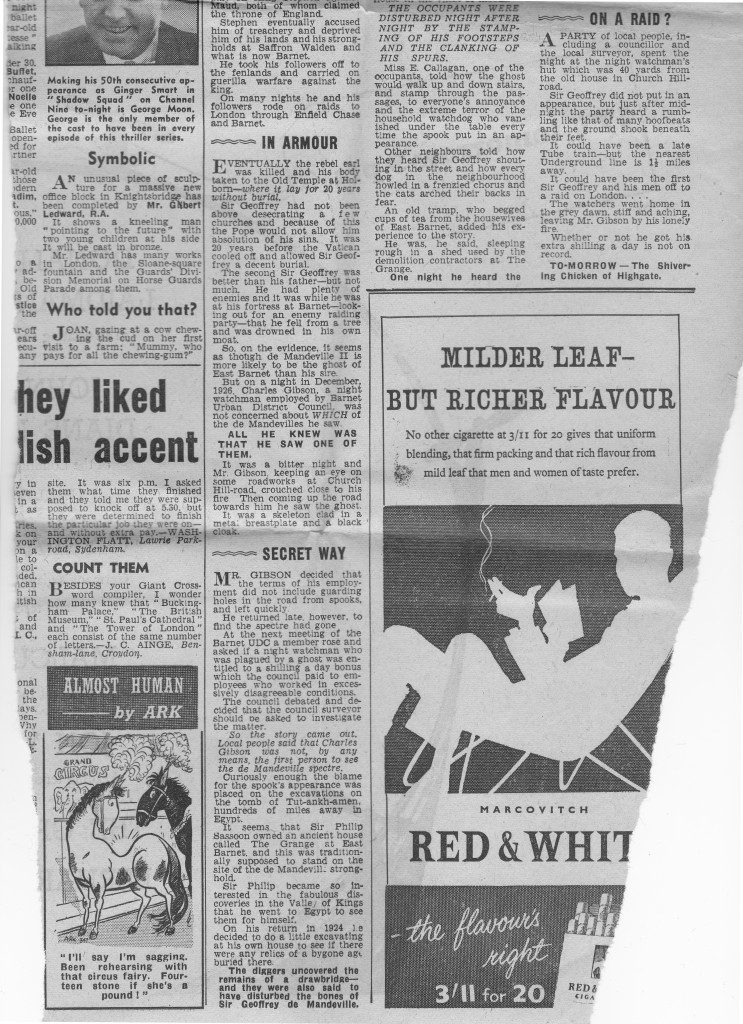

The next tale is from Pond Square, Highgate and starts with the experience of Aircraftman Terence Long in December 1943. Walking through Pond Square he heard the sudden pulling up of a carriage and then a frightening shriek. Moonlight revealed the sight of a ghostly chicken – “It was a frightened, squawking fowl, dashing about in frenzied circles, half running, half flying, and shivering.”

The unlikely story of the chicken goes back to the 17th century when Francis Bacon was riding through the snow covered streets of Highgate. Pondering scientific questions, he suddenly asked his coachman to stop and fetch a chicken. The chicken was killed, and Bacon promptly stuffed it with snow and then put it in a bag filled with more snow. This experiment was following Bacon’s observation that the grass underneath snow always appeared fresh and he wondered whether snow and the cold could help with the preservation of food.

Whilst working on this experiment in the cold Highgate night, Bacon collapsed and was taken to the home of Lord Arundel in Pond Square where he died a few days later.

The chicken has since been seen many times in Pond Square, although why the chicken continues to haunt rather than Francis Bacon is a bit of a mystery.

The next story moves into central London, to Covent Garden underground station and tells the story of the ghost of the Victorian actor, William Terriss.

On November 24th 1955, the foreman ticket collector Jack Hayden was in the staff mess room which was divided in two with a partition which included a door when, “This door was open and in the other section of the room there appeared the figure of a tall man, grey of face and wearing white gloves.” Jack Hayden and a colleague who had also seen the ghost were shown a photo of Terriss and immediately recognised him. William Terriss had been murdered at the nearby Adelphi Theatre.

Along with the ghost story, this cutting from the Evening News includes a fascinating advert for “Trips by Trains” and includes:

– Football excursions to see Sheffield United play Leyton Orient from St. Pancras. Grimsby Town play Charlton from King’s Cross and Colchester United play Brentford from Liverpool Street.

– There is a train leaving Paddington to see the Passing-Out Parade of Naval Apprentices at H.M.S Fishguard, Torpoint

– A Sunday timetable of trains, mainly with buffet cars from the main London stations

– weekday trains to the “Hants & Dorset Resorts”

This was when a train ticket from Waterloo to Bournemouth would have cost 15 shillings.

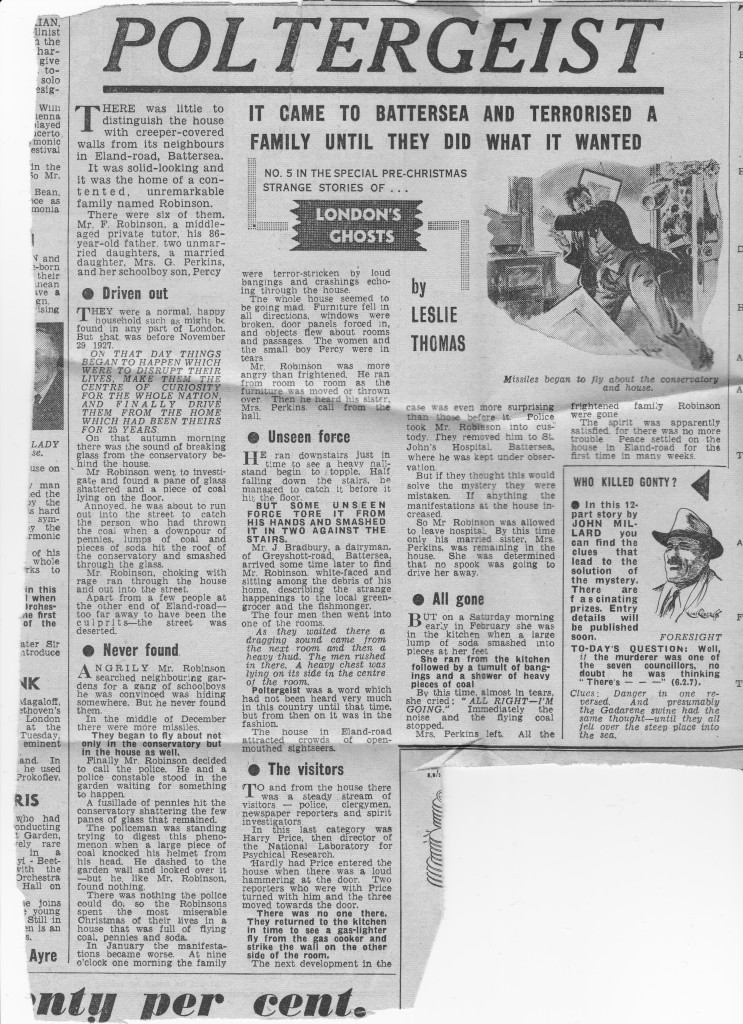

The next story is from south London and starts with the terrifying headline “It came to Battersea and terrorised a family until they did what it wanted.”

The haunting at the house in Eland Road, Battersea owned by the Robinson family, started on the 27th November, 1927 with breaking glass in the Conservatory, which was followed by flying coal, pennies and soda, loud noises and bangs, furniture falling in all directions, broken windows and door panels.

Mr Robinson called in the Police who were also subjected to flying coal, but could not do anything to help, so “the Robinsons spent the most miserable Christmas of their lives in a house that was full of flying coal, pennies and soda.”

Despite a steady stream of people trying to help, police, clergymen and spirit investigators, nothing could be done. There were also newspaper reporters and crowds of “open-mouthed sightseers.”

Members of the family tried to stay in the house, but were gradually driven out. The last to stay, a Mrs Perkins, was hit by a large lump of flying soda – “She ran from the kitchen followed by a tumult of banging’s and a shower of heavy pieces of coal. By this time, almost in tears she cried ‘Alright I’m going’ immediately the noise and the flying coal stopped.”

With the family who lived in the house now gone the spirit was satisfied and peace descended on the house in Eland Road.

Leslie Thomas went on to publish 30 novels until his death in 2014. These articles highlight some of his earliest writings for the Evening News, nine years before publication of The Virgin Soldiers.

They also tell of some of the many possible ghostly encounters you may experience walking the streets of London after dark.

alondoninheritance.com