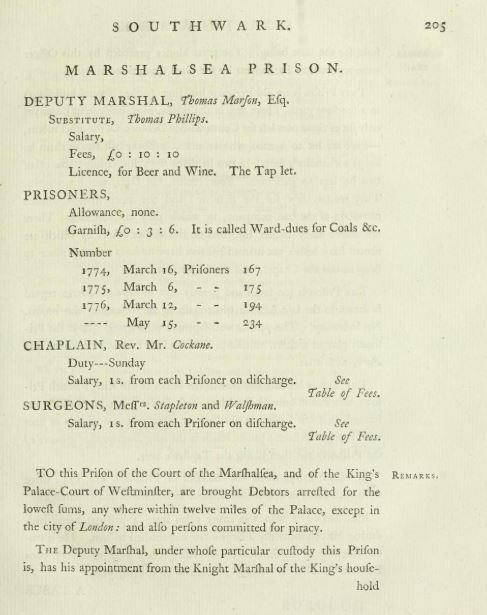

For today’s post, I am at the highest point in the metropolitan London area, standing opposite Jack Straw’s Castle.

Jack Straw’s Castle was one of the most well known pubs around Hampstead Heath. A coaching inn as well as a place for those walking across the heath to visit, along with weekend and Bank Holiday crowds.

My father photographed the building just after the last war and the photo below is his view of Jack Straw’s Castle in 1949.

This was my view in March 2019:

You may well be wondering how I know that my father’s photo is of Jack Straw’s Castle, given the changes between 1949 and 2019, however if you look at the very top of the tallest building, the faded words Jack Straw’s Castle can just be seen. Also, the building on the far left of both photos, along with the brick wall with two pillars, are the same in both photos.

My father’s photo shows the pub as it was following bomb damage in 1941 and subsequent demolition of some of the walls to make the building safe. The Daily Herald on the 29th March 1941 carried a report titled “Jack Straw’s Castle Bombed – the old Hampstead hostelry, was among places recently damaged during air-raids. Its neighbour, Heath House, the home of Lord Moyne, leader of the House of Lords, was also damaged.”

The building was demolished and rebuilt in 1964 to a rather striking design by Raymond Erith, however it is no longer a pub, having been converted into apartments and a gym. The building is Grade II listed which has helped to preserve key features of Erith’s design, despite developers trying to push the boundaries of how much they could change.

Jack Straw, after who the pub was named, is a rather enigmatic figure. General consensus appears to be that he was one of the leaders of the Peasants Revolt in 1381, however dependent on which book or Internet source is used, he could either have led the rebels from Essex, or been part of the Kent rebellion. Jack Straw may have been another name for Wat Tyler and some sources even question his existence. Any connection with Hampstead Heath and the site of Jack Straw’s Castle seem equally tenuous – he may have assembled his rebels here, made a speech to the rebels before they marched on London, or escaped here afterwards.

Jack Straw is mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in the The Nun’s Priest’s Tale of The Canterbury Tales:

Out of the hyve cam the swarm of bees.

So hydous was the noyse — a, benedicitee!

Certes, he Jakke Straw and his meynee

Ne made nevere shoutes half so shrille

Whan that they wolden any Flemyng kille

Given The Canterbury Tales were written not long after the Peasants Revolt, this reference by Geoffrey Chaucer does probably confirm his existence. The reference to “Flemyng kille” is to the targeting of the houses of Flemish immigrants in London by the rebels.

I cannot though find any firm evidence of Jack Straw’s association with Hampstead or the site of the pub.

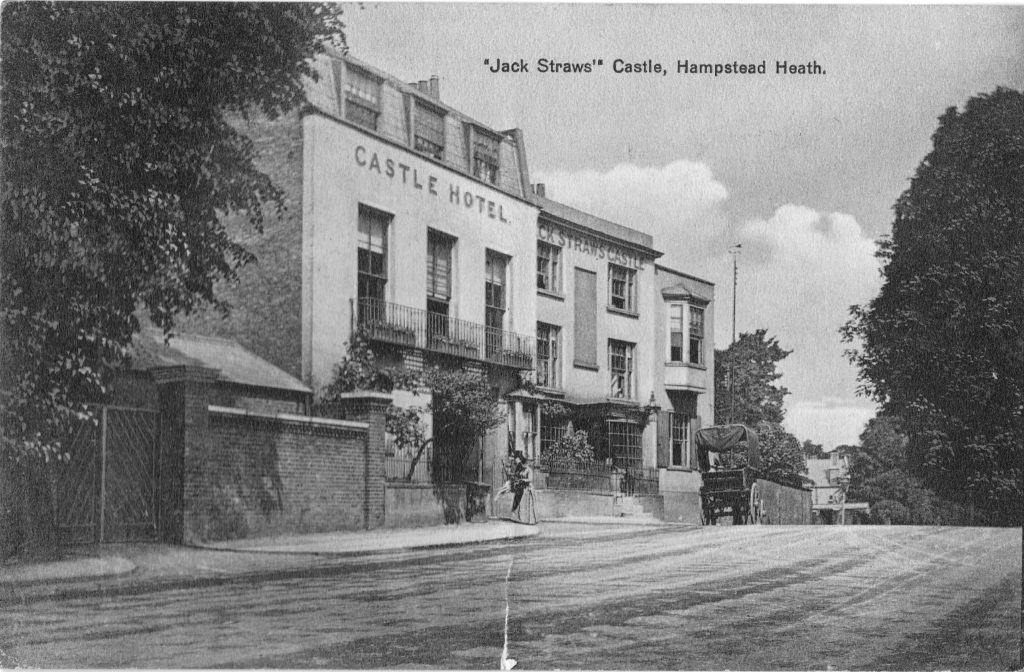

My father’s photo was of a rather sad looking building, however before the bombing of 1941, Jack Straw;s Castle was a rather lovely coaching inn. The following photo is from a postcard from around or just before the First World War showing Jack Straw’s Castle, and demonstrating that part of the series of buildings was the Castle Hotel.

It all looks rather idyllic. A cart is parked outside, a well dressed couple are entering the Castle Hotel, and there are small trees and plants growing in frount of the buildings. The road to Golders Green disappears off past the buildings.

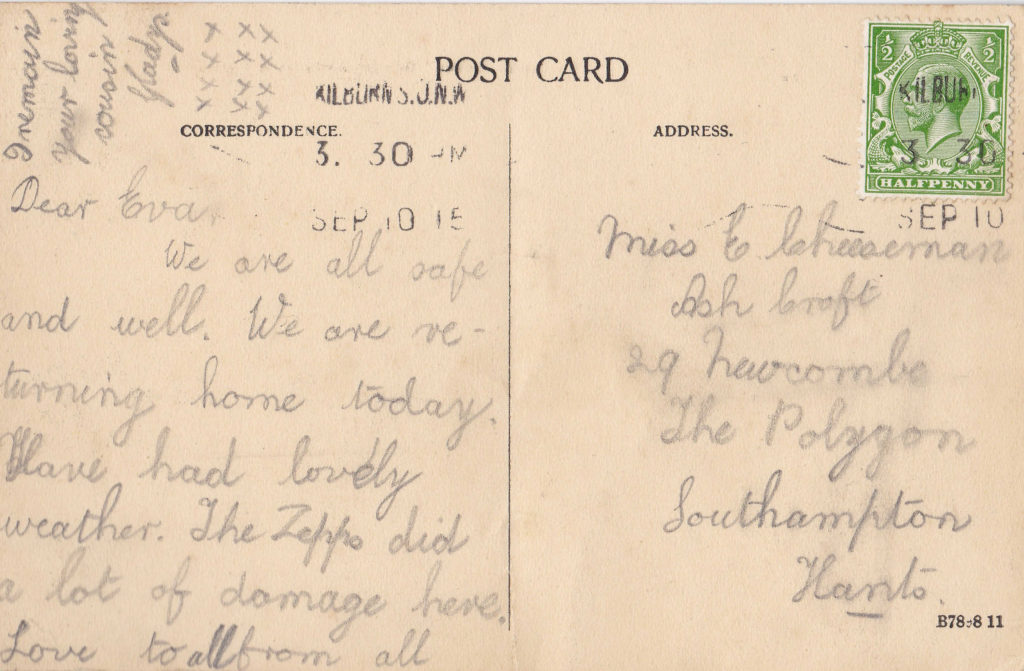

The rear of the postcard reveals that London was not so idyllic when it was posted. The card is dated 10th September 1915 and the author has written “The Zeppo did a lot of damage here”, probably referring to the raid on the 8th September 1915 when a Zeppelin attacked London, dropping the largest bomb to land on the city during the first war, with the raid killing 22 people in total.

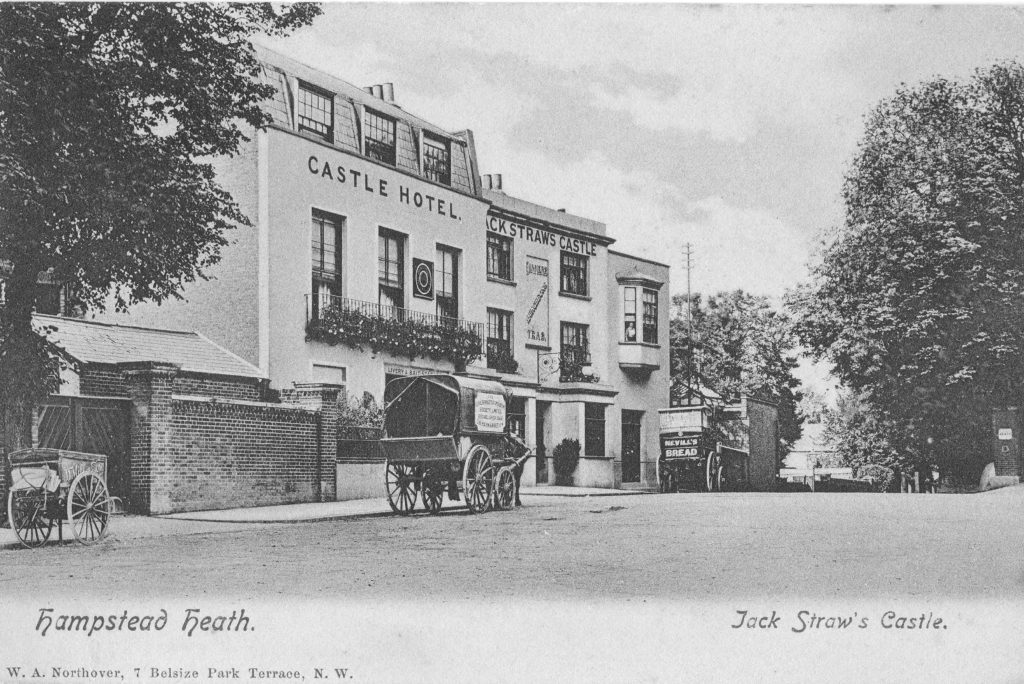

A later photo than the above postcard as the pub has now lost the bay windows on the ground floor and has the windows that would remain in my father’s photo.

The two carts in the above photo possibly delivering Nevill’s Bread to Jack Straw’s Castle and Hotel, along with a delivery from the Civil Service Cooperative Society.

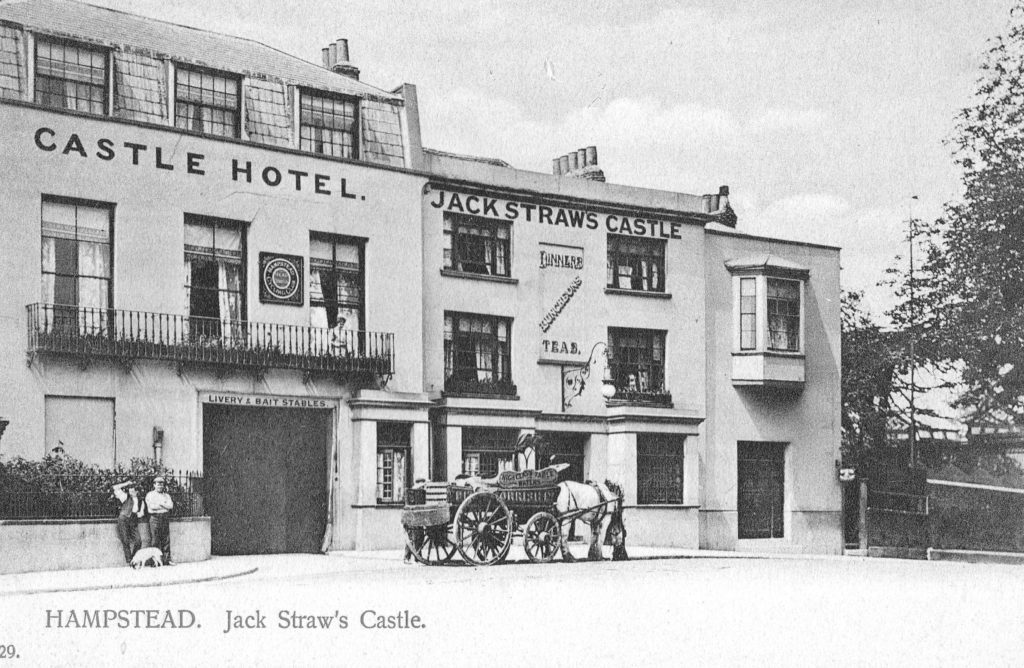

In the following photo, the cart is delivering High Class Table Waters.

The above photo shows how there are frequently traces of previous buildings in the buildings we see today. Jack Straw’s Castle was a Coaching Inn, and the large doors on the left have “Livery & Bait Stables”, but compare the position of these large doors with my 2019 photo above and you will also see a large set of doors in roughly the same position, although the 1964 version of Jack Straw’s Castle had no need to provide a stables.

A view of Jack Straw’s Castle, the origin of the name and some of the visitors to the inn is provided by Edward Walford in Old and New London (published in 1878);

“To Hampstead Heath, as every reader of his ‘Life’ is aware, Charles Dickens was extremely partial, and he constantly turned his suburban walks in this direction. He writes to Mr. John Forster: ‘You don’t feel disposed, do you, to muffle yourself up and start off with me for a good brisk walk over Hampstead Heath? I know of a good house where we can have a red-hot chop for dinner and a glass of good wine.’ ‘This note’ adds Forster, ‘led to our first experience of Jack Straw’s Castle, memorable for many happy meetings in coming years.’

Passing into Jack Straw’s Castle, we find the usual number of visitors who have come up in Hansoms to enjoy the view, to dine off its modern fare, and to lounge about its gardens. The inn, or hotel, is not by any means an ancient one, and it would be difficult to find out any connection between the present hostelry and the rebellion which may, or may not, have given it a name. The following is all that we could glean from an old magazine which lay upon the table at which we sat and dined when we last visited it, and it is to be feared that the statement is not to be taken wholly ‘ for gospel’ – Jack Straw, who was second in command to Wat Tyler was probably entrusted with the insurgent division which immortalised itself by burning the Priory of St. John of Jerusalem, thence striking off to Highbury, where they destroyed the house of Sir Robert Hales, and afterwards encamping on Hampstead heights. Jack Straw, whose castle consisted of a mere hovel, or a hole in the hill-side, was to have been king of one of the English counties – probably of Middlesex; and his name alone of all the rioters associated itself with a local habitation, as his celebrated confession showed the rude but still not unorganised intentions of the insurgents to seize the king, and, having him amongst them, to raise the entire country.

This noted hostelry has long been a famous place for public and private dinner-parties and suppers, and its gardens and grounds for alfresco entertainments.”

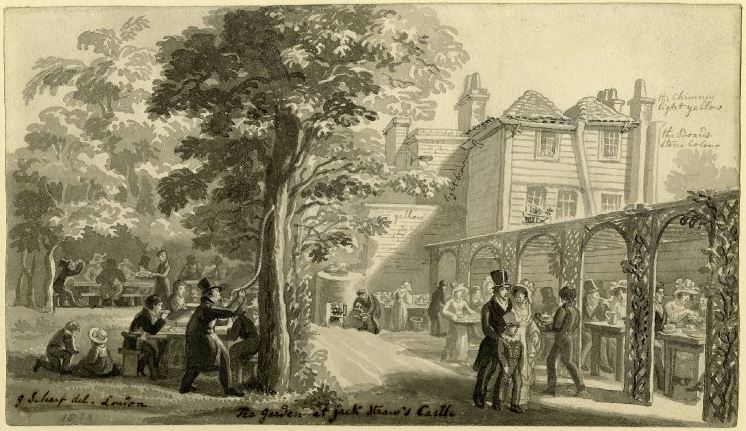

Gardens at the back of pubs and inns have probably been a popular attraction for as long as these establishments have existed, and today a pub with a garden is a perfect place to spend a summer’s evening or weekend afternoon. The garden at the back of Jack Straw’s Castle looks perfect in this drawing from 1830 by George Scharf (©Trustees of the British Museum).

The drawing is interesting as it appears to contain notes for a later coloured version. Scribbled text alongside the building record that the chimney is light yellow, the boards are stone colour and the brick wall is yellow.

Jack Straw’s Castle was obviously a local landmark in what was a very rural area. The following print from 1797 showing an old cottage surrounded by trees and bracken and is labelled “Near Jack Straw’s Castle, Hampstead Heath” as the inn was probably the only local reference point (©Trustees of the British Museum).

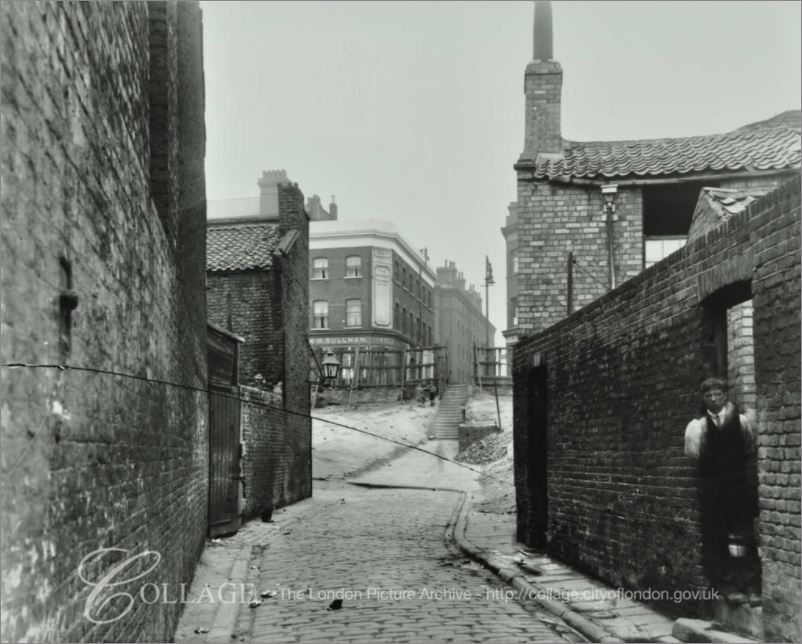

My father’s photo was of the building just after the war showing a shadow of the former inn. The following photo from 1941 shows Jack Straw’s Castle in 1941 in the days following the bombing.

The windows have been blown out, but difficult to see what other damage has been caused to the structure of the building. From this photo I would have expected that Jack Straw’s Castle could have been repaired, however shortage of materials and people during the war probably prevented any repair work, and over the years any structural damage and the building being left in this state resulted in the building being unsafe, and walls demolished to result in the building that my father photographed.

Although Jack Straw’s Castle is very different, the buildings to the left look as if they are much the same as their original construction.

There appear to be four individual houses in the above photo. The name adjacent to the entrance is “Old Court House”. The Victoria County History volume for Hampstead refers to these buildings as having been built by Thomas Pool who purchased Jack Straw’s Castle in 1744 and built two houses in 1788. The Victoria County History states that in 1820 they were converted into a single house, with name changes over the years of Heath View, Earlsmead, and finally Old Court House.

Underneath the name plate is an intercom system with four buttons so I assume they are four individual homes, but how and when they converted from the original two houses to the current buildings, I am unsure.

Jack Straw’s Castle sits on a very busy road junction, where roads from Hampstead, Highgate and Golders Green converge. Whilst I was trying to take photos there was a continuous stream of traffic.

In the following photo, the road on the left leads to Golders Green, the road on the right leads to Highgate (passing a building which is still a pub – the Spaniards), and I am standing by the road that leads up from Hampstead.

After visiting Jack Straw’s Castle, I walked down into Hampstead. This took me alongside Whitestone Pond.

The pond was originally named Horse Pond as it was a drinking point for horses on the passing road, I will find the origin of the new name in a moment.

This area is the highest point in London, with according to the Ordnance Survey map, the pond being at 133m above sea level and Jack Straw’s Castle being at 135m.

It was originally fed by rain water and dew, however I believe it now also has an artificial supply as the height of the pond means there was no natural underground or stream sources of water.

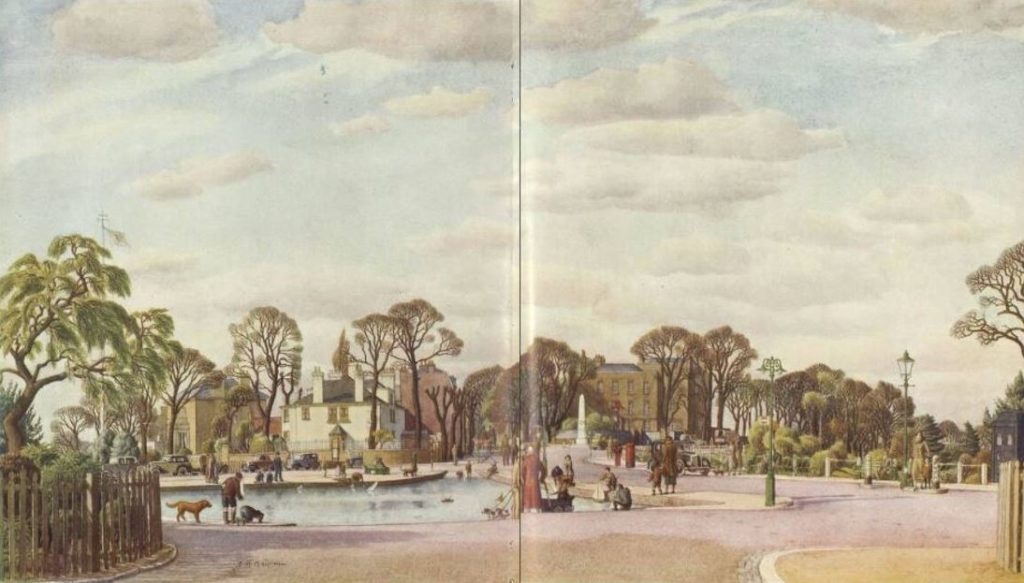

This view dates from 1936 and shows Whitestone Pond, with the side of the Old Court House and Jack Straw’s Castle in the distance.

I took the following photo of the same view, but I have no idea why I stupidly did not move to get the tree in a different position as it is obscuring the war memorial which can be seen in the distance in the 1936 view.

Just to the left of where I was standing for the above photo, is the source of the name Whitestone Pond.

This is a milestone and states “IV miles from St Giles, 4 1/2 miles 29 yards from Holborn Bars”. There is a similar milestone near the Flask pub in Highgate (see my post here) which gives a distance of 5 miles from St Giles Pound. These two milestones show that there were two main routes, either side of Hampstead Heath, leading down to St. Giles and then via Holborn, into the City.

There is one final unexpected find before heading off down into the centre of Hampstead, close to the milestone is a covered reservoir with an unusual looking dome on top.

This is the astronomical observatory of the Hampstead Scientific Society – a rather unique place to observe the night sky, high above the rest of London. One of the very few locations across London that provides public viewing. Unfortunately, the observatory is currently closed whilst restoration work is carried out.

It is a shame that Jack Straw’s Castle is no long a pub. It is an impressive building in an equally impressive location – although I must admit that i prefer the pre-war building. I have read so many different interpretations of the origin of the name Jack Straw and possible associations with Hampstead so i suspect we will never know the truth behind Jack Straw, but it is good that there is still a very visible reminder of the Peasants Revolt at the highest spot in Hampstead, 638 years after the event.