The area to the north of St. Paul’s Cathedral was destroyed during the war, mainly due to the use of incendiary bombs on the night of the 29th of December 1940. The destruction covered ancient streets such as Paternoster Row and Paternoster Square, and the shells of buildings were demolished and removed leaving a wide open space ready for new development.

The site was redeveloped during the 1960s, with the pre-war streets and original architectural styles being ignored, with an office complex built which followed a number of post war City planning themes which I will come on to later in the post.

The 1960s development was not popular, obstructed key views of the cathedral and tended to separate the cathedral from the area to the north. The buildings were not that well maintained and by the late 1980s the area was not an attractive place to work, or walk through, and did nothing to enhance the cathedral just to the south.

In the early 1990s, a proposed Masterplan was published by “Masterplanners” Terry Farrell, Thomas Beeby and John Simpson & Partners, and Design Architects Robert Adam, Paul Gibson, Allan Greenberg, Demetri Porphyrious and Quinlan Terry.

I have a copy of the Masterplan and it is fascinating to compare the original proposals with the site we see today. Not quite so architecturally ornate as the Masterplan, but very similar to what was originally proposed, and (in my view) a significant improvement on the 1960s development.

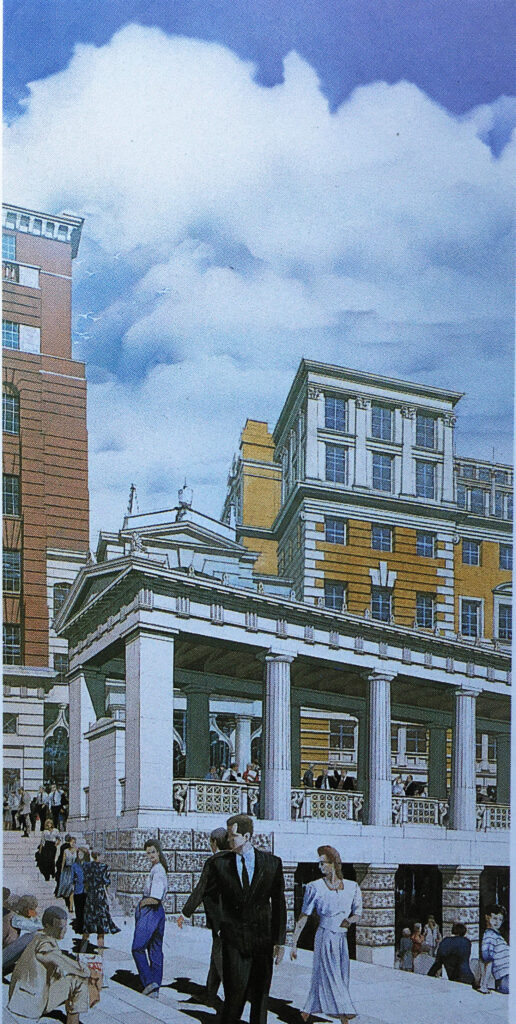

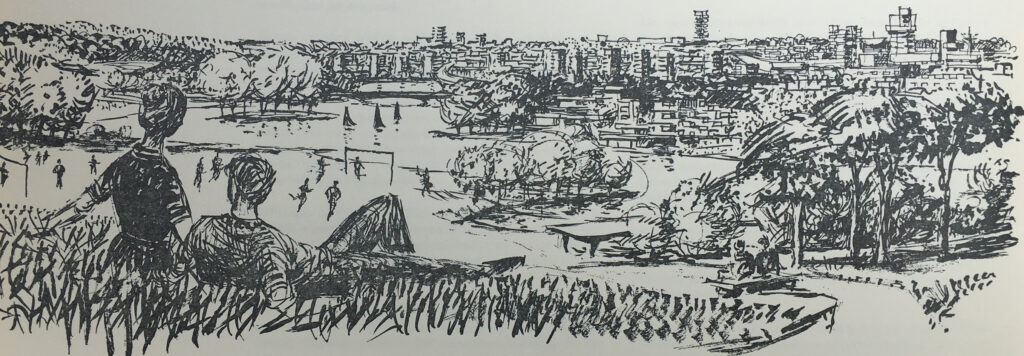

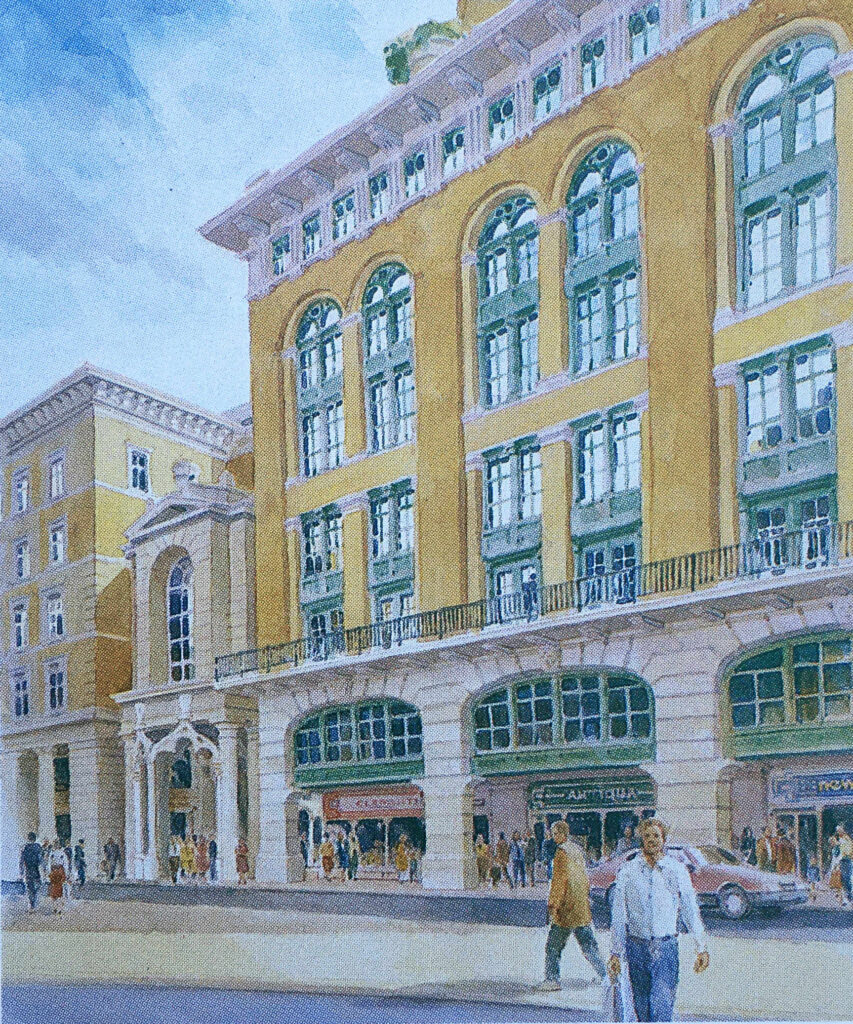

The following image is from the Masterplan and shows a “View of Paternoster Square looking south-east to the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral”. The image is by Edwin Venn.

As with City developments such as the Barbican and Golden Lane estates, the damage inflicted on the City during the last war created the large area of space which could take a major, transforming development, rather than the simple rebuild of individual buildings.

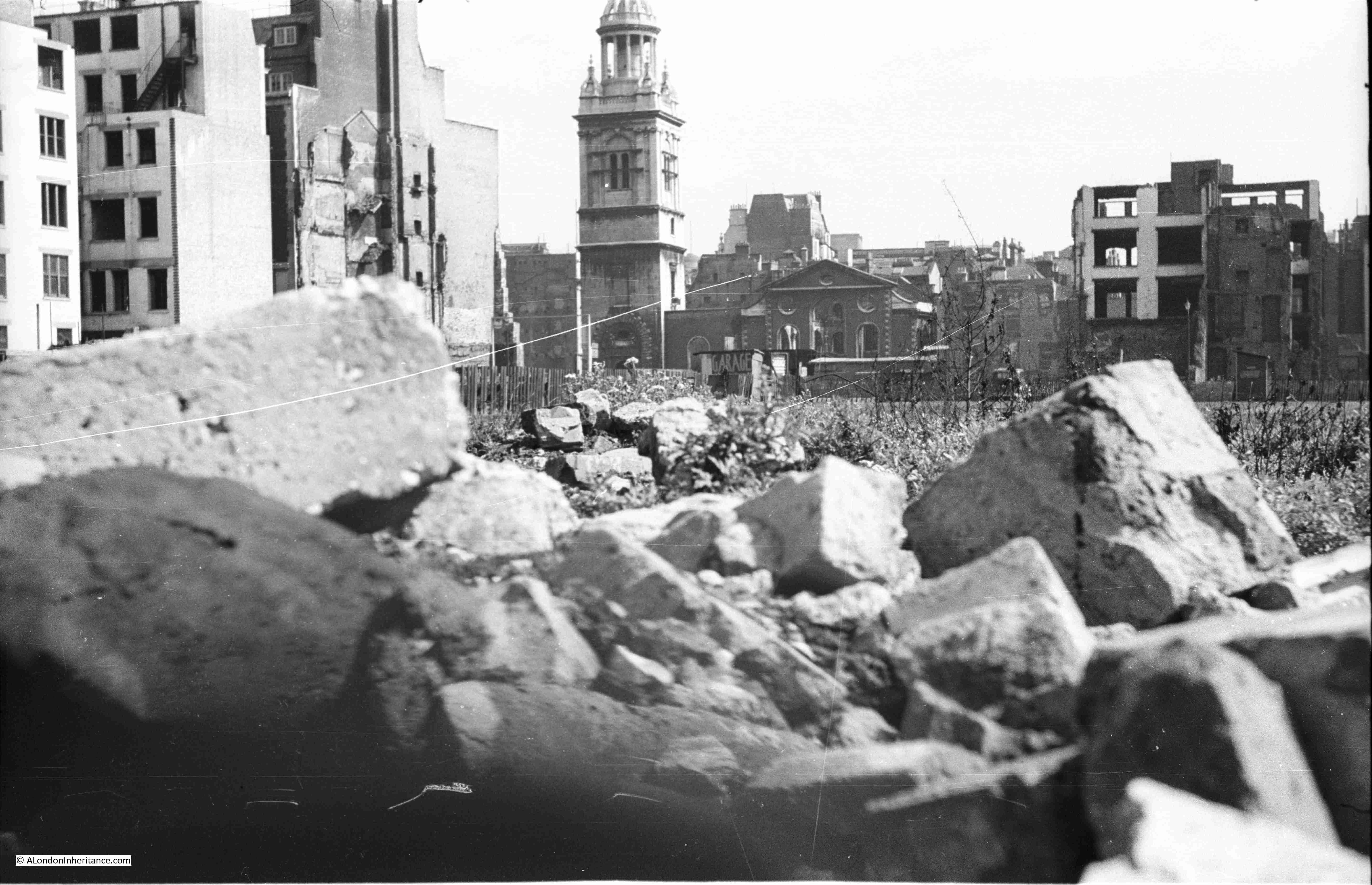

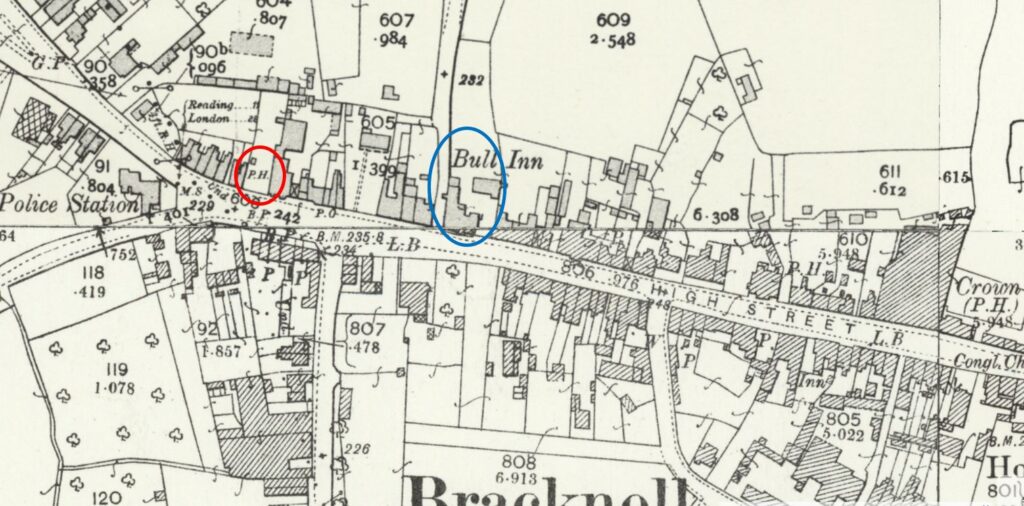

The following photo is one of my father’s, taken from the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral:

The shell of a building at the bottom left is the Chapter House of the Cathedral.

The circular features between what was Paternoster Square and the remains of the Chapter House are the outline of water tanks that were placed on site during the war to provide supplies of water for firefighting.

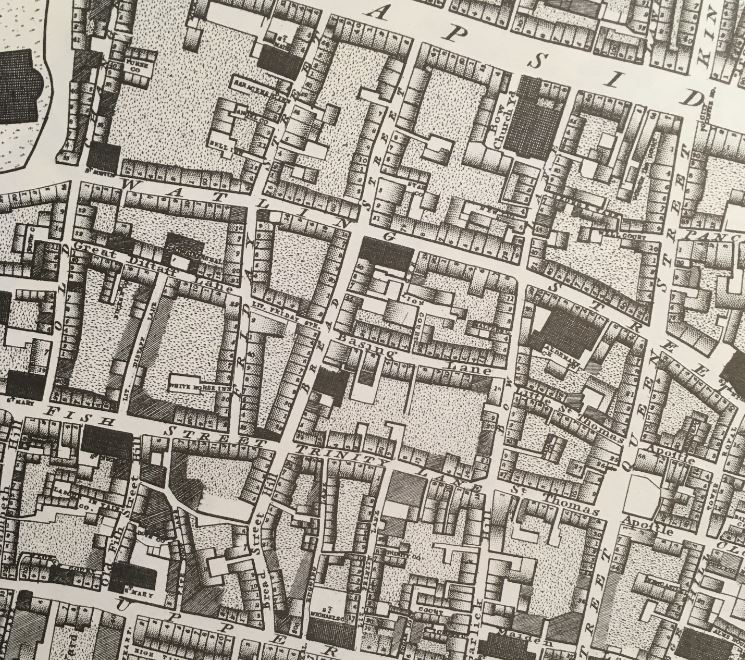

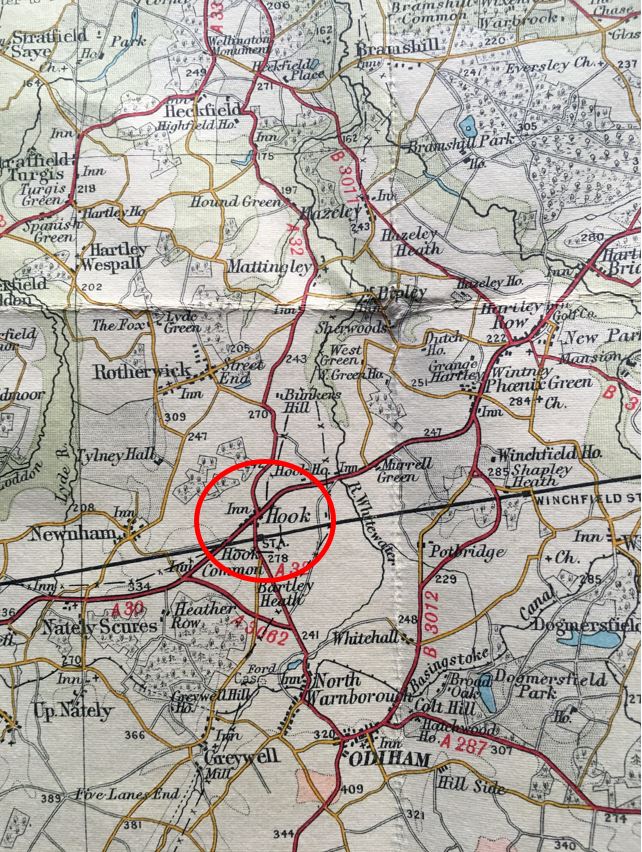

The following extract from Bartholomew’s 1940 Reference Atlas of Greater London shows the area to the north of the cathedral. In the map, a Paternoster Square can be seen. In the above photo, this is the rectangular feature at top left, with roads on all sides, but not a building in sight.

As well as Paternoster Square, the map shows a network of streets such as Ivy Lane, Three Tuns Passage, Lovells Court and Queens Head Passage.

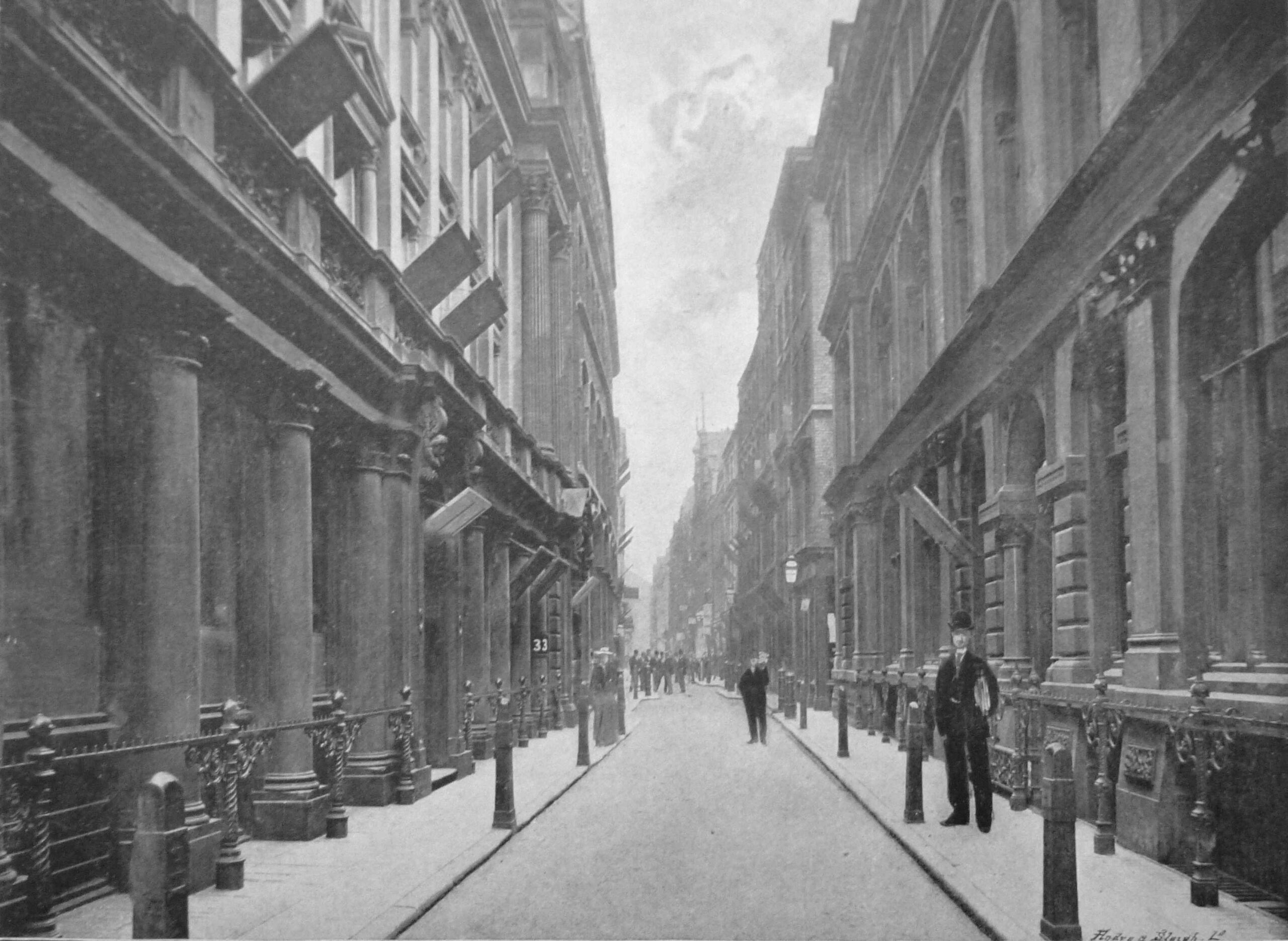

Running across the area was Paternoster Row, and the following photo from the book, the Queen’s London, published in 1896, shows the view along Paternoster Row, a narrow street but with substantial 19th century City office buildings on either side.

In the following photo, the dense network of streets and buildings to the north of the cathedral can be seen:

Another of my father’s views from the Stone Gallery, looking slightly above the earlier photo, with a bus running along Newgate Street. The Paternoster Square developments would occupy the area to the south of Newgate Street.

The same view today, showing the buildings of the Paternoster Square development:

The area, and street names are of some considerable age. The first written records of the streets date from the 14th century, with Paternosterstrete in 1312 and Paternosterrowe in 1349.

From the early 19th century onwards, the area was home to many publishers, stationers and book sellers. Much of the stock held by these businesses contributed to the fires started on the 29th of December 1940.

Harben’s Dictionary of London references a Richard Russell dwelling there in 1374 and described as a “paternosterer”, and that paternosterers were turners of beads, and gave the street its name.

Harben also states that “A stone wall was found under this street at a depth of 18 feet running towards the centre of St. Paul’s. A few yards from this wall in the direction of St. Martin’s-le-Grand wooden piles were found covered with planks at a depth of 20 feet”, and that under Paternoster Square, “Remains of Roman pavements and tiles were found in 1884”.

W.F. Grimes’ book, about his post war excavations across the City, “The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London” records his limited excavations across the area in 1961 to 1962, and that much of the Paternoster area “was not available for examination because the cellars had retained their bomb rubble and the sites around Paternoster Square had become a garage and car parks.”

In the limited excavations that did take place, Grimes found evidence of ditches and post holes, possibly where the wooden piles were found in the 19th century. He concludes that the area was probably occupied by timber framed buildings rather than stone.

The main discovery on the site was a hoard of about 530 coins, “mainly barbarous copies of coins of the Gallic Empire of the late third century A.D.”

The limited excavation took place prior to the 1960s development of the site. This create a dense cluster of office blocks between the cathedral and Newgate Street, which can be seen in the following photo, to the right of the cathedral:

The 1960s development of the site was based on the plans by architect and planner Lord Holford who was commissioned by the City Corporation to advise them on architectural policy, and the development of buildings within the “orbit of the dome of St. Paul’s”.

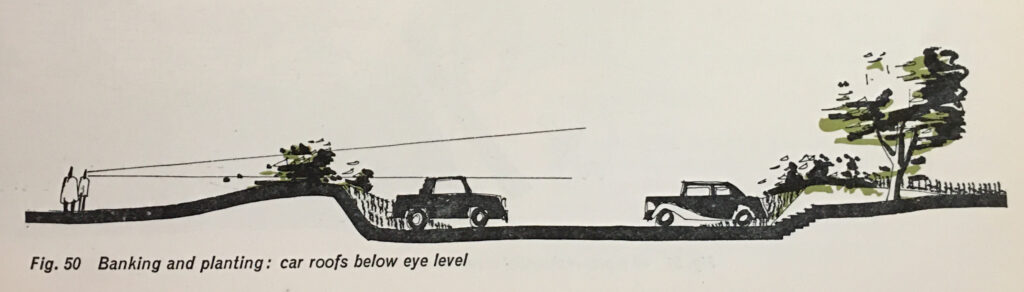

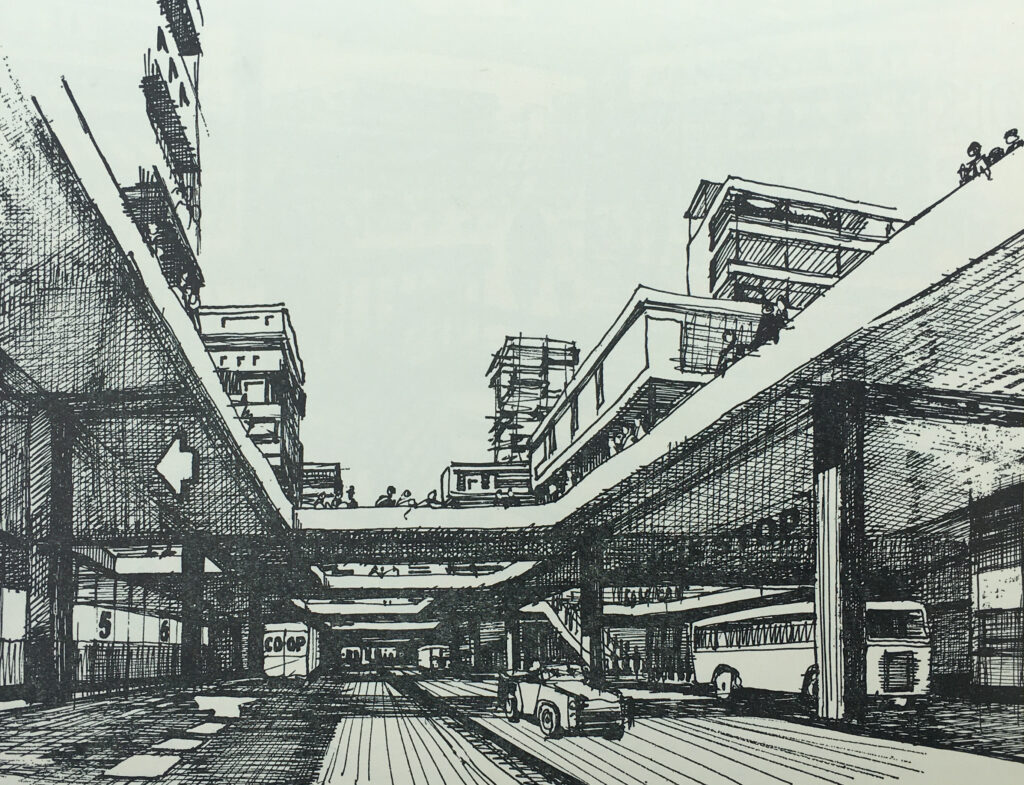

Lord Holford’s plan for the site followed post-war thinking about the City’s redevelopment. This included the separation of traffic and pedestrians, with vehicles having priority at ground level, and pedestrians moved to elevated walkways.

The original street plans were rejected in favour of a rigid matrix of building blocks, which resulted in a horizontal slab of blocks with the 18-storey office tower Sudbury House being the highest.

Lord Holford’s explanation of his approach to the design of the site was that “there is more to be gained by contrast in design, than from attempts at harmony of scale or character of spacing” (I think this is the design approach used for the current developments between Vauxhall and Battersea Power Station).

Not all of Holford’s ideas were implemented, and many of the buildings were by other architects, so the new development ended up as a rather uninspiring addition to the land north of the cathedral.

The following photo shows the 1960s office block immediately to the right of the old St. Paul’s Chapter House:

In the following photo, the Chapter House is the older building in dark brick behind the tree, and the new lighter red brick building to the right occupied the site of the 1960s office block seen in the above photo:

The following photo shows one of the access ramps that took pedestrians up to the pedestrian area. To the right is the lower vehicle route, with access to car parking:

I may be completely wrong, but I vaguely remember there being a pub on the upper pedestrian area, which had an outside area with a view over the surrounding streets.

The 1960s development took no regard of the views of the cathedral just to the south.

This is the view to the northern entrance to the cathedral, with only a small part visible through a tunnel that takes a pedestrian walkway through an office block:

In the Masterplan, the proposed redevelopment delivers this alternative view of the same part of the cathedral:

And whilst the buildings are less ornate than originally proposed, the view today is much the same as in the Masterplan, also with a café, on the site of the walkway:

The caption to the following illustration reads “St. Paul’s Church Yard will be re-aligned and the Cathedral gardens re-laid and enclosed”:

The gardens were re-laid and enclosed, and new office blocks occupied the space to the north, and whilst these were very different to the 1960s versions, they were not quite as ornate as the Masterplan envisaged:

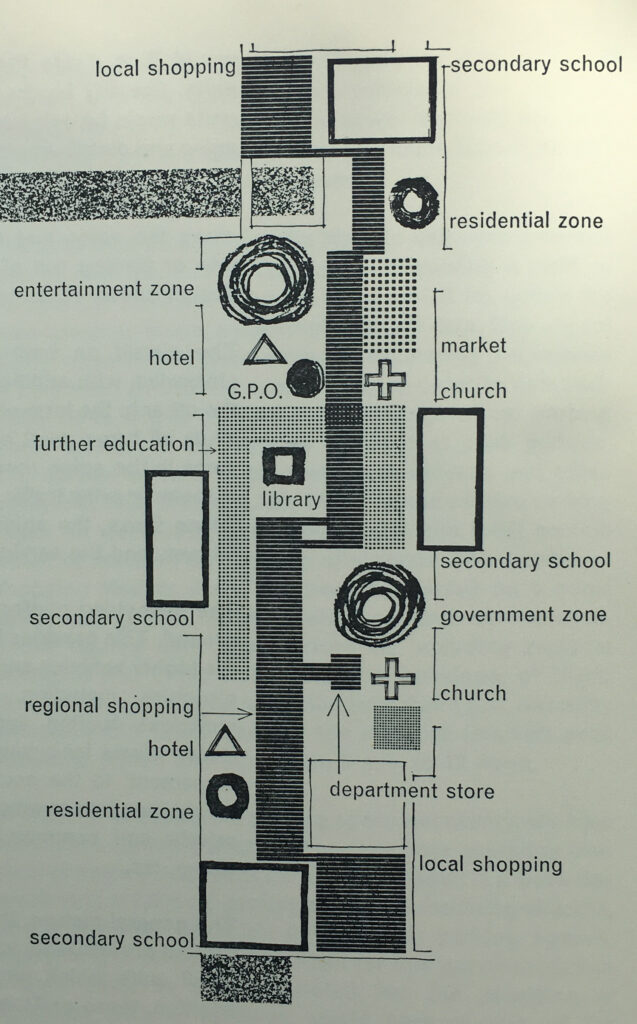

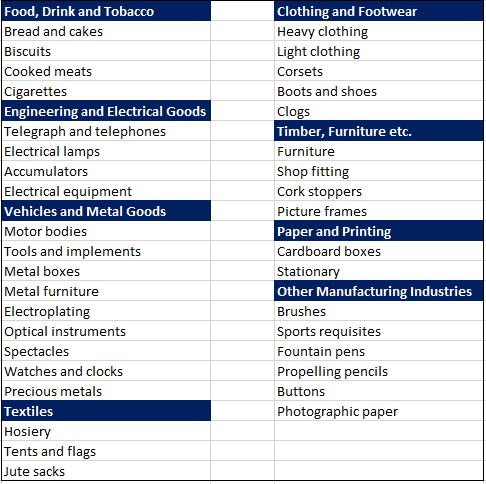

The objectives of the Masterplan were to:

- Restore views of St. Paul’s Cathedral from Paternoster Square at ground level and on the skyline, respecting St. Paul’s Heights and Strategic Views

- To create buildings that are in harmony with St. Paul’s Cathedral

- To restore the traditional alignment of St. Paul’s Church Yard and the Cathedral Gardens creating an enhanced public space

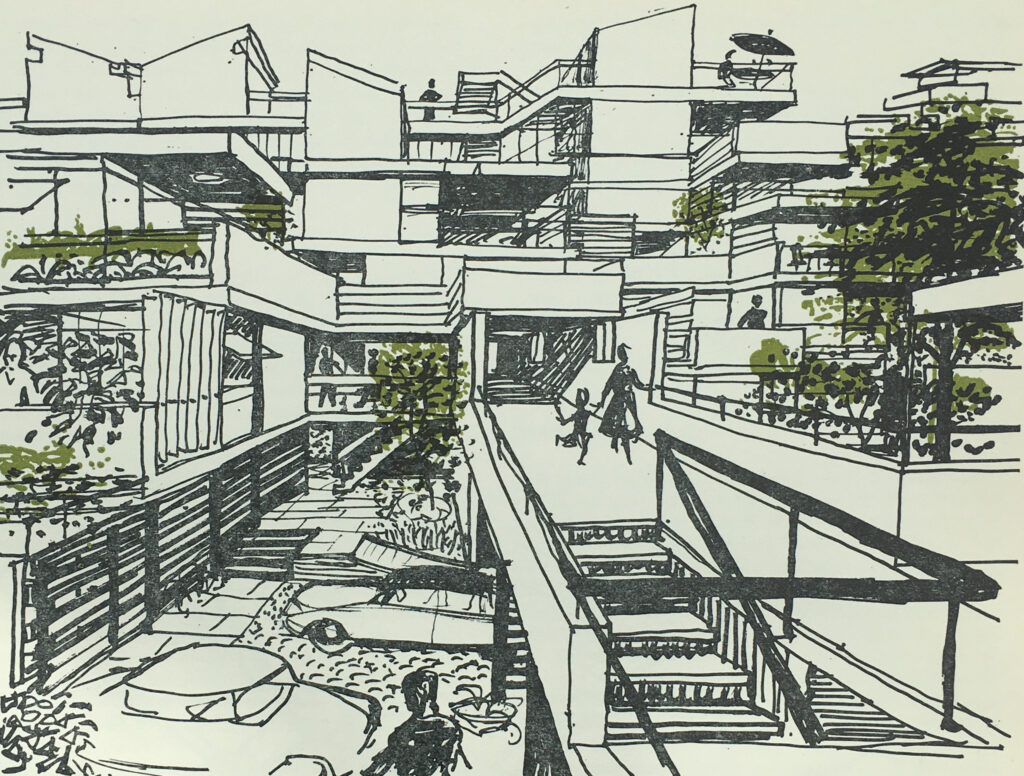

- To re-establish a traditional street pattern and return pedestrian routes into the site to ground level

- To create a new, traffic-free, public open space allowing ease of access, especially for the disabled

- To follow the City tradition of classical architecture, using traditional materials such as stone, brick, tile, slate and copper

- To be flexible enough for key corners, outside the Planning Application site to be integrated at a later date

- To create a thriving new business community in the best traditions of City life

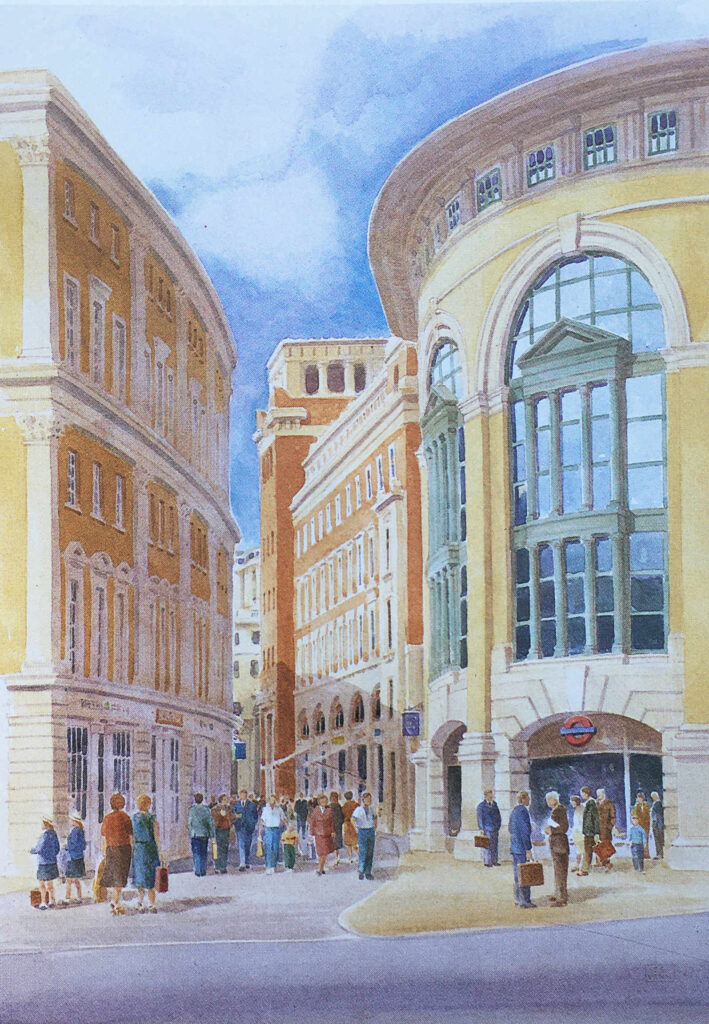

- To create a much-needed, new shopping area in the heart of the City, with a variety of shops, restaurants and entertainment, linked into St. Paul’s Underground Station

- To create new open public spaces for relaxation and enjoyment by office workers, visitors and shoppers alike

It is interesting to compare the development today with these objectives.

There was an intention to follow the City tradition of classical architecture, and this could be seen in the illustrations of the planned buildings, such as the following example showing “the frontage of the new buildings on Newgate Street”:

The frontage along Newgate Street today is comprised of standard office block design, without the classical architecture proposed in the Masterplan.

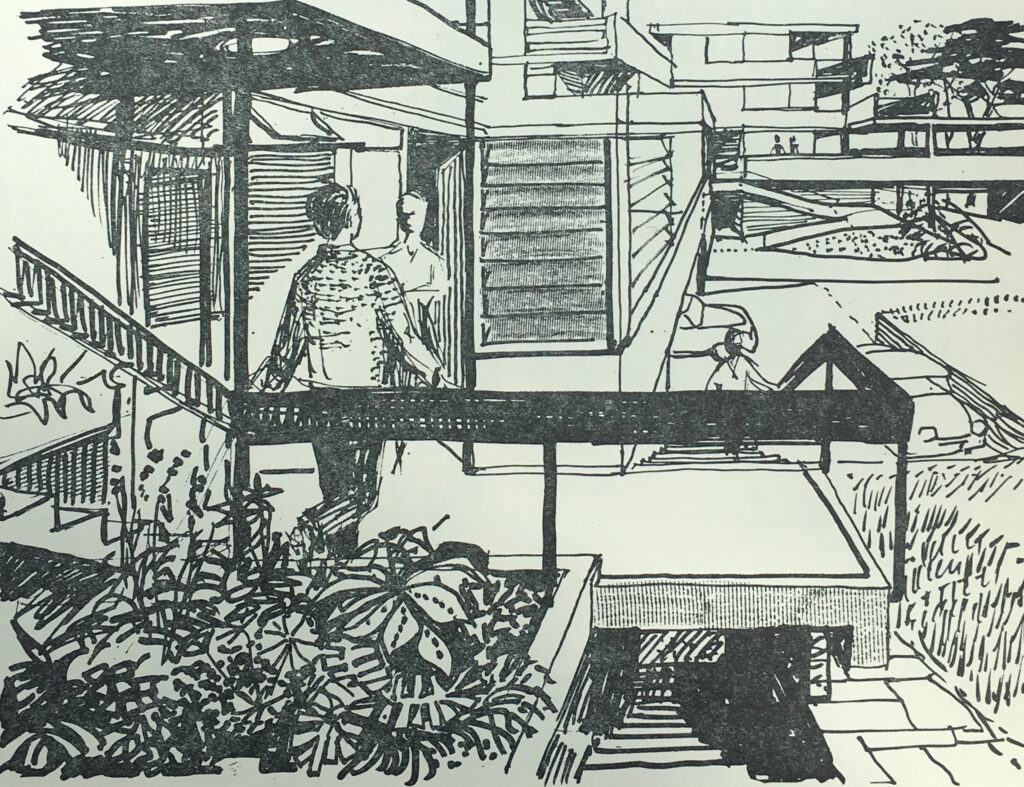

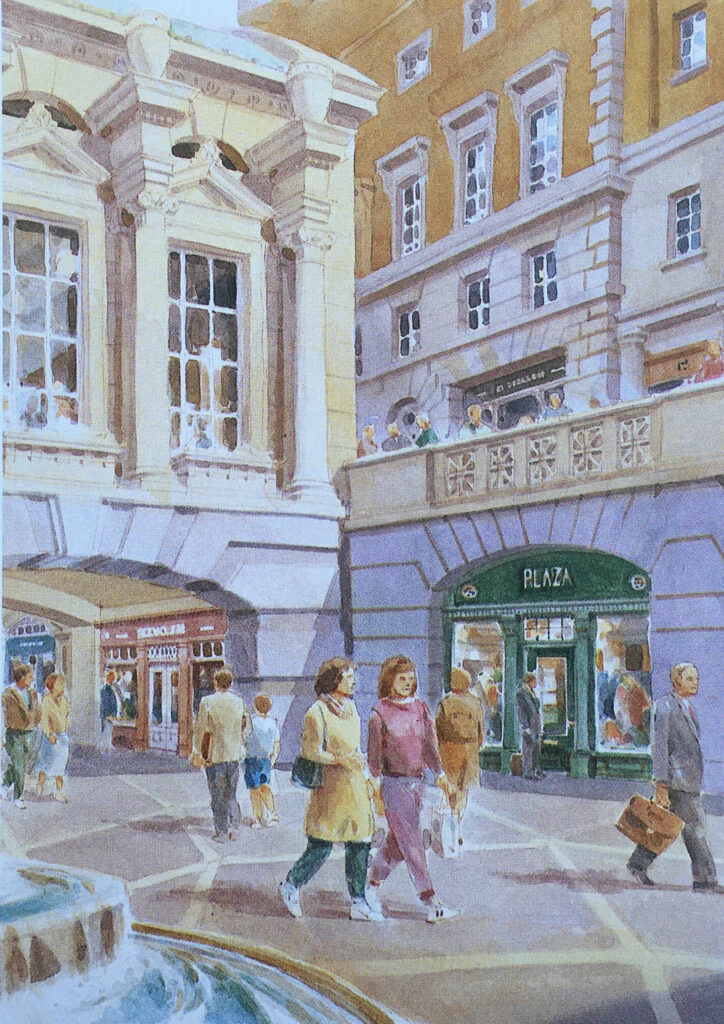

The title of the following illustration is “A Meeting Place – Paternoster Square will provide a social focus for the City, a place to meet friends and colleagues, to browse or to use the health club”:

This approach can be seen across the Paternoster Square development, but in less ornate settings. Whilst the buildings do not have the same classical architectural styling, they do make use of stone, and there is a considerable amount of brick throughout the site which is a pleasant change from the glass and steel of many other recent City developments:

Whereas today, Paternoster Square is at a single level, in the Masterplan it was intended that there would be steps leading down to a Lower Court, so whilst the plan did away with the upper pedestrian and lower vehicle levels of the 1960s development, it did retain different levels, but for pedestrians. The Lower Court:

The plan was that Paternoster Row would become almost a continuation of Cheapside.

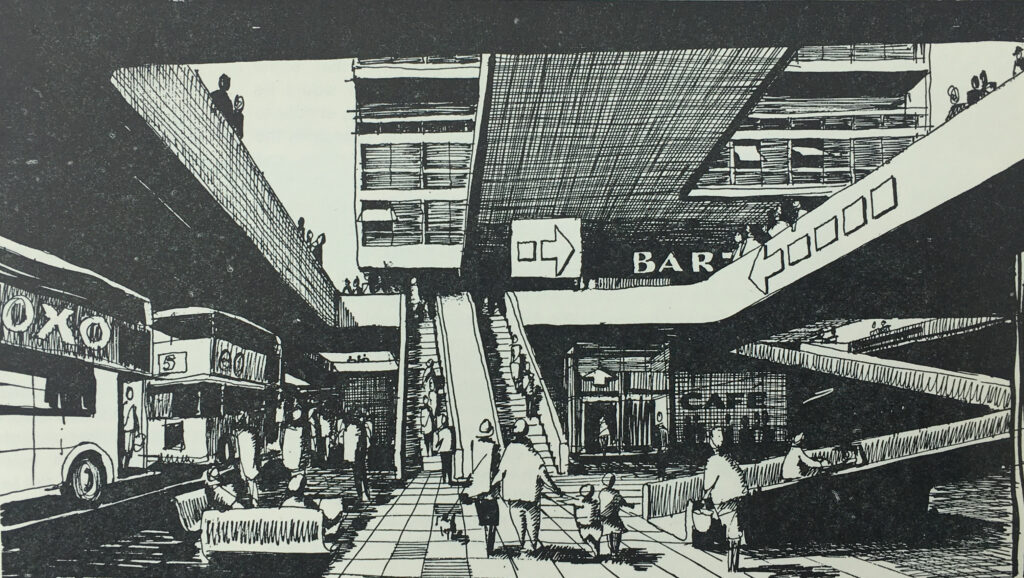

Cheapside was, and to an extent still is, the main shopping space of the City, and the One New Change development has enhanced this, but in the Masterplan, shopping would continue from Cheapside, across the road into Paternoster Row, and the underground station, which today is reached via a separate access point to the edge of the development, would have been integrated into the plan, as shown in the following illustration:

The St. Paul’s Chapter House was reduced to a shell of a building, as shown in my father’s photo, however it was restored and survived the 1960s redevelopment, and was included in the Masterplan, where it can be seen in the centre of the following illustration.

To the left of the Chapter House is a rather ornate three storey gateway into Paternoster Square, which today has been replaced by Temple Bar.

Temple Bar was included as an option in the Masterplan, which is described as “currently in a state of decay in a Hertfordshire Park”.

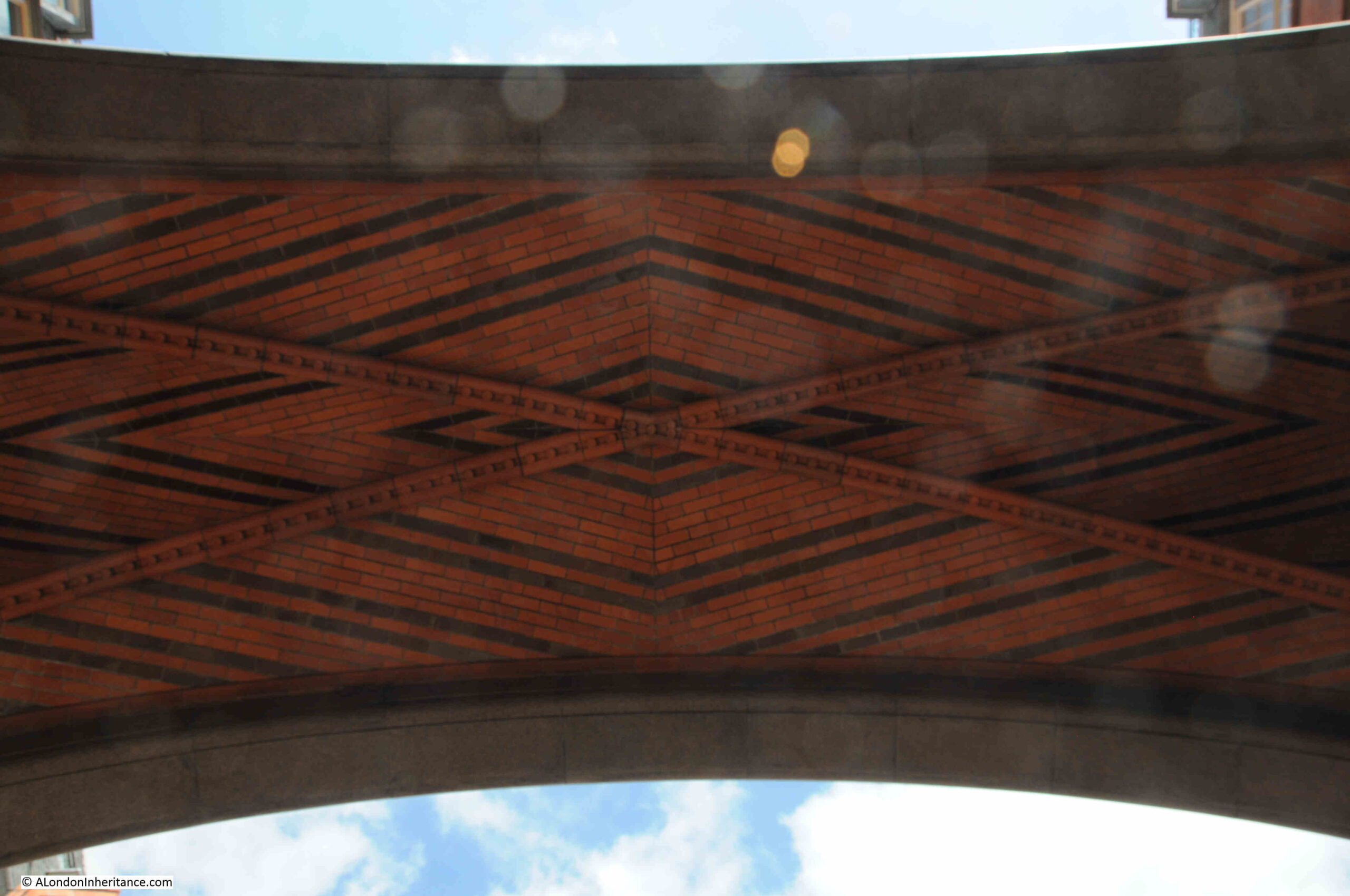

As mentioned earlier, the central Paternoster Square was intended to be multi-level, and in the following illustration, there is a rather impressive Loggia (an outdoor corridor with a covered roof and open sides), that would have provided a lift down to the Lower Court, would provide shelter, and would mark the access point to the Lower Court:

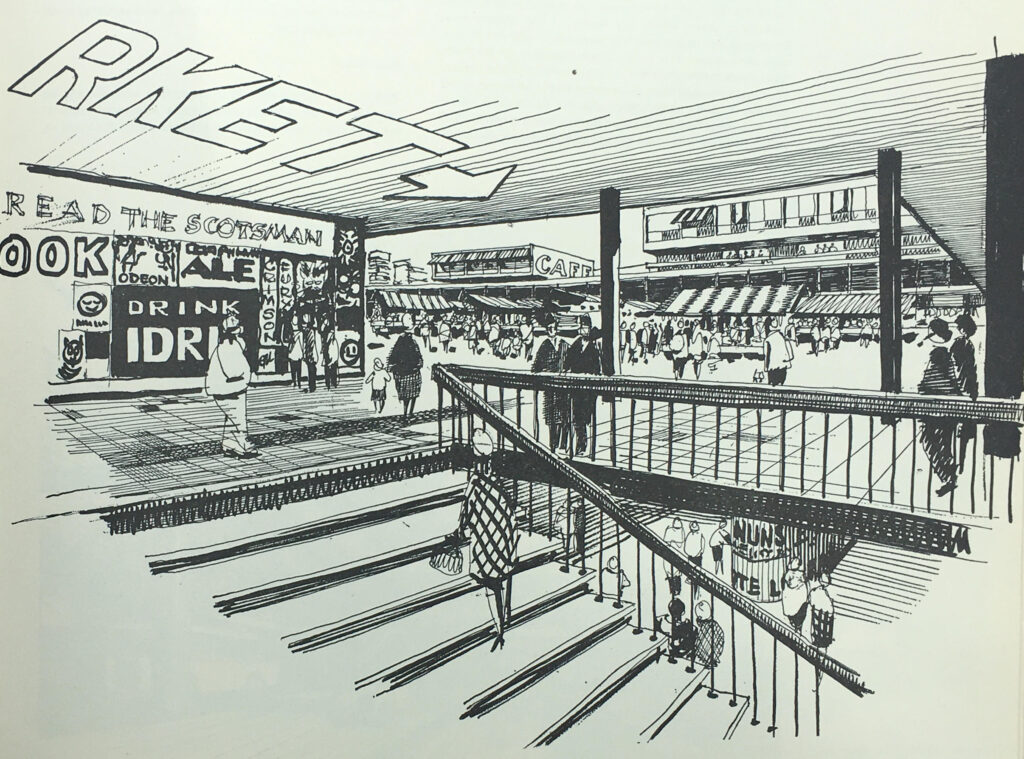

A key aim of the Masterplan was to bring life back to the area, and one of the ways to do this was via retail, and the plan stated that “Paternoster Square will be established as one of the foremost shopping areas in central London. There will be more than 80 shops, including a quality food hall or department store”.

The approach to retail included a Shopping Avenue, which was a covered route between the Lower Court and St. Paul’s Underground Station:

Shops would also line the new Paternoster Row:

And along the route of the old Ivy Lane, there would be Ivy Lane Arcade “designed in the tradition of famous London arcades. It will attract specialty shops such as jewelers and galleries”:

And shopping around Paternoster Square and Lower Court:

The Paternoster Square estate does have some shopping, but far less than was intended in the original Masterplan. There is no lower court and no covered shopping avenues.

Most of the shops are either restaurants, bars or take away food and coffee shops, aimed at local office workers and at the number of visitors who pass through as part of a visit to the area around St. Paul’s Cathedral.

There are also many other differences. Whilst the overall concept appears the same, the classical building style is now very limited as is the overall decoration across the buildings and ground level pedestrian spaces.

In 1995, the owners of the land commissioned Whitfield Partners to deliver a Masterplan for redevelopment, and it is the outcome of this plan that we see today. Similar in concept, but different in implementation.

The Paternoster Square development today has a large central space, is pedestrianised, and some of the pedestrian walkways do roughly align with some of the original pre-war streets.

The objective of bringing life back to the area has been achieved, and during the day it is generally busy with local workers, visitors and tourists, and on a summer’s afternoon, the bars and restaurants are particularly busy.

The central square features a 23.3 metre tall column, which conceals air vents to the parking space below the square:

The Masterplan by Farrell, Beeby and Simpson included a Loggia which would have provided a lift down to the Lower Court, and mark the access point to the Lower Court.

Whilst the Loggia and Lower Court were not part of the implemented Masterplan, there is a covered way along the northern edge of the square which has similarities to the original Loggia:

In the above photo, two groups of tourists with guides can be seen to the right. Between them is the artwork “The Sheep and Shepherd” by Elisabeth Frink. This came from the earlier Paternoster Square development as it was installed on the north side of the estate in 1975 when it was unveiled by Yehudi Menhuin.

It was moved to the high walk outside the Museum of London in 1997 prior to demolition of the 1960s estate, then returned to Paternoster Square in 2003.

The Sheep and Shepherd stands where Paternoster Square joins to Paternoster Row (which, as far as I can tell is very slightly north of the street’s original alignment).

Looking through the Loggia that was built as part of the new development:

Rather than lots of classical decoration to the buildings, there is a “Noon Mark” on one of the buildings to the north of the square. In strong sunlight, at midday, the shadow indicates roughly the day of the year:

A key point with the development is the height of the buildings. In the 1960s development, there were office blocks that ran both parallel and at right angles to the cathedral and views of the cathedral were limited.

With the new development, building heights are lower and allow views of the cathedral. As can be seen in the following photo from the north west corner of Paternoster Square, the new buildings are just slightly higher than the original Chapter House (the older, dark brick building to the right of the column):

Whilst a number of the walkways do roughly align with the original streets, Paternoster Square is in a different place to the original square, which would have been to the northwest of the current square, to the right of the building in the following photo, which does retain some classical styling at ground level, but is a modern building above:

This is the view from the western end of Paternoster Lane towards the central square. This stretch of walkway is almost exactly on the original route of Paternoster Row:

Sometimes it seems as if all the large sculpture across London’s streets is there to hide an air vent. This is the purpose of the column in the central square and also the purpose of a work of art on the corner where Paternoster Lane meets Ave Maria Lane:

This is a 2002 work by Thomas Heatherwick, and consists of sixty three identical isosceles triangles of stainless steel sheet welded together.

Round to the front of St. Paul’s Cathedral, and to the north of the large open space in front of the cathedral is an office block with shops at ground level which follows the alignment of the old street St. Paul’s Churchyard:

The following photo is taken from Cheapside looking towards the cathedral and Paternoster Square development, and may offer a clue as to why the implemented Masterplan is different to the Masterplan of Farrell, Beeby and Simpson:

To the right of the above photo are two sides of an octagonal building. It can be seen in the following extract of the photo of the 1960s estate:

One of the entrances to St. Paul’s Underground Station is just to the right of the building in the photo, and the building is either part above, or extremely close to, the underground station.

I have no evidence to confirm this, however it may be that the estate we see today was down to cost.

Whilst the initial planning permission did not include the octagonal building, the Masterplan did. It would have been demolished and the entrance to St. Paul’s Underground Station would be integrated into one of the new buildings as can be seen in one of the earlier pictures. The proposed lower shopping arcade would also have led into the underground station.

I imagine that anything involving changes to an underground station incur significant extra planning time and costs.

The overall Paternoster estate, whilst aligning with the original Masterplan, does not have the level of classical architecture proposed in the plan, or the split level with the lower court.

All this extra work would have incurred cost, and in so much of the built environment, decisions often come down to cost.

Having said that, compared to the 1960s development, Paternoster Square is a very considerable improvement.

It integrates well with the cathedral to the south, recreates alignments close to some of the original streets, certainly has brought life back into the area from what I recall of the previous development, and is a generally pleasant space to walk through.

Reading the Masterplan though, it is interesting to speculate what might have been, if this plan had been adopted.

You may be interested in the following posts about the area around St. Paul’s:

Post War London from the Stone Gallery, St. Paul’s – The North and West

Post War London from the Stone Gallery, St. Paul’s – The South and East