For this week’s post in my August journey around the country, I am visiting two historic locations that are day trips to the west of London, Winchester and Stonehenge. Winchester on the side of the M3 heading down towards Southampton and Stonehenge on the road to the west country, the A303.

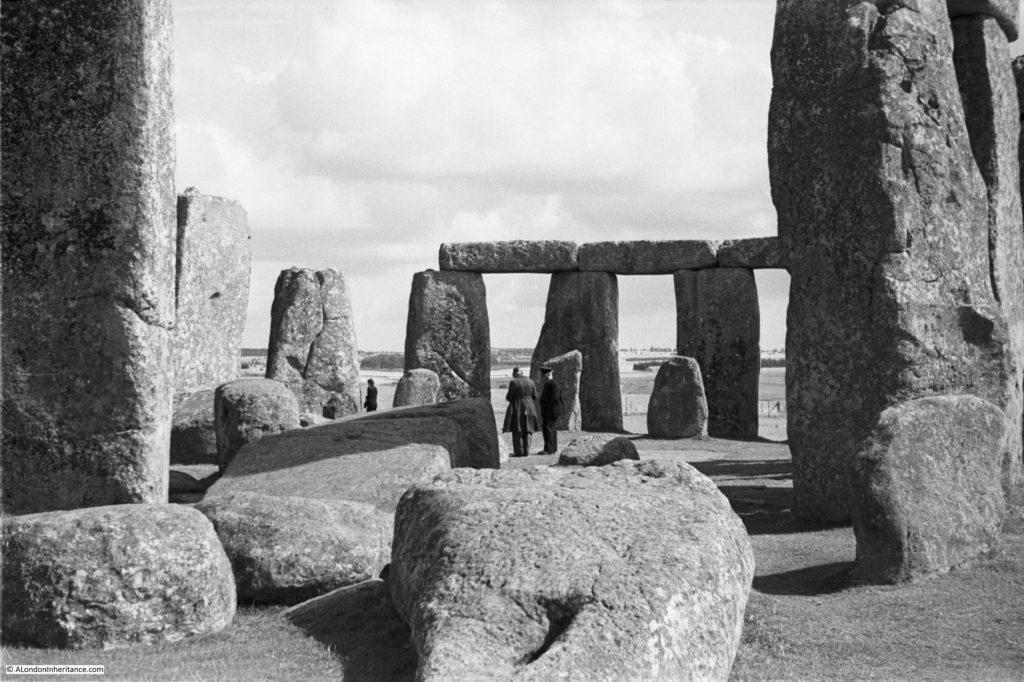

My first stop is at Stonehenge. The following photos were taken by my father in 1949. Whilst the stones are the same today, the environment is very different. When these photos were taken, visitor numbers were very low and the visitor had free access to walk among the stones. The two roads that ran either side of Stonehenge were quiet without the long queues of traffic that are a feature of most summer weekends.

I must admit I did not revisit Stonehenge for this post, having last been there a number of years ago. Today, it is only possible to walk among the stones during specific events and for the general visitor the view is limited to a path that runs a short distance around the stones.

Stonehenge is always busy with coaches of visitors providing a continuous stream of people to walk around the circle. Whilst fully understandable that the protection of the stones required their separation from those who have come to visit, it must have been much more of an experience being able to walk among and admire the size and positioning of these stones, without crowds and without the thunder of traffic on the adjacent road.

Stonehenge has seen recent improvements. One of the roads that passed either side of the stones, the A344, has been closed and is returning to grassland. The visitor centre has been relocated some distance away, thereby helping provide the stones with some of the original sense of how they stood in their landscape. This still leaves the heavy traffic on the A303. Tunnels and alternative routes for removing the A303 from the landscape have been proposed and discussed for years, but nothing ever seems to get to the point of general agreement as to the best route, financed and into construction. If the Government wanted to get on with some infrastructure investment then a long tunnel to take the A303 away from the Stonehenge landscape must be a good option.

I have been trying to work out who the two people in the following photo could be. The man on the right could be a chauffeur judging by his clothing, the man on the left looks to be wearing a long coat and some form of leather hat.

The following photo from Britain from Above taken in 1946 provides a view of a quieter Stonehenge than today, however a solitary coach on the now closed A344 provides an indication of what is to come.

There are numerous theories as to the original purpose of Stonehenge – astronomical calendar, religious or ceremonial site however I suspect we will never know for sure.

The history of the next place is relatively recent when compared with the age of Stonehenge. It is though well documented. This is Winchester, reached from London via Waterloo if travelling by train, or the M3 by car.

Winchester has a long history. A Roman town, Venta Belgarum, occupied an earlier settlement. An Anglo-Saxon Minster was built on part of the area now occupied by the Cathedral from the 7th to the 11th century with a new cathedral being built in the 11th century, the Cathedral that with subsequent rebuilding and alterations forms the current Winchester Cathedral.

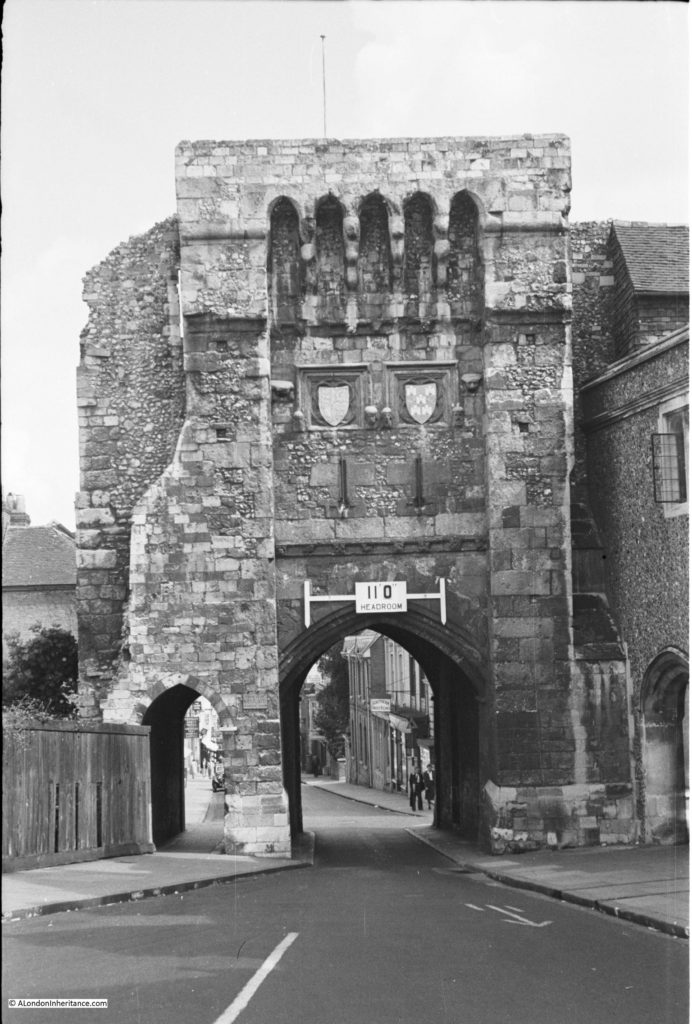

For my brief tour of Winchester, I will start at the far western end of the High Street at the West Gate – my father’s original photo:

The West Gate today. Originally, all traffic would pass through the West Gate and whilst this worked when there was little traffic of limited width, it would not be a suitable route into the centre of Winchester for today’s traffic. The buildings to the left of the gate were demolished and the road now bypasses the gate leaving it as the pedestrian route into the centre of the city.

Passing through the West Gate and we can look down Winchester High Street. The landscape descends down to the River Itchen that flows through the city at the far end of the High Street.

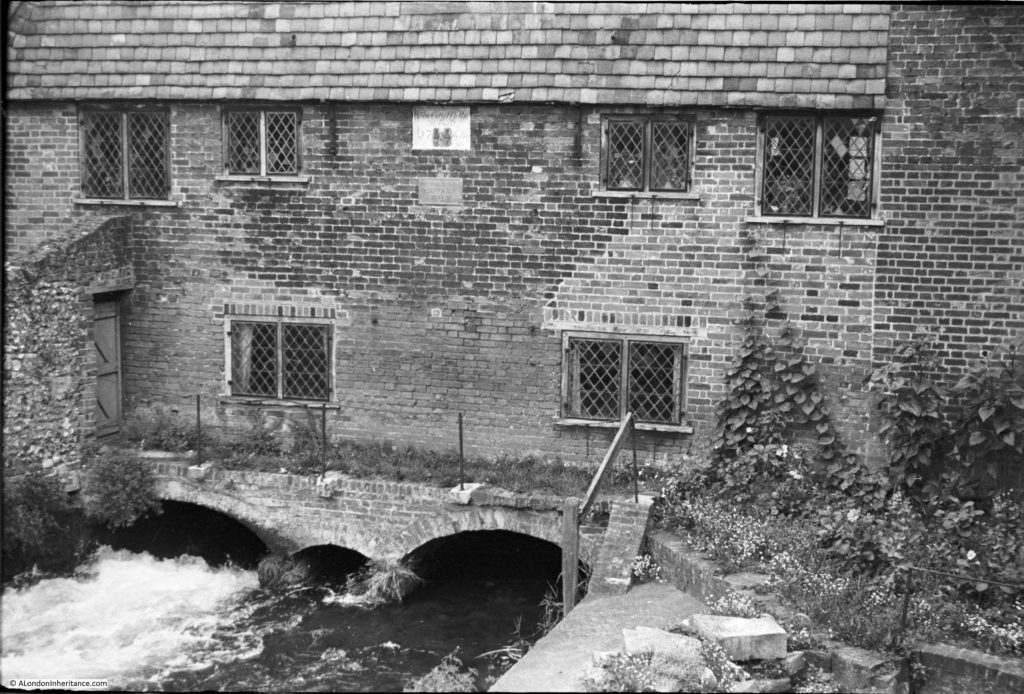

And it is the River Itchen that we meet now, passing underneath the Winchester City Mill. A mill was recorded on the site in Saxon times and it appears that a mill has operated on the site for the majority of the years since. The present building was constructed in 1743.

The Mill became the first Youth Hostel of the London region of the Youth Hostel Association in 1931, continuing as a hostel till 2005 when the mill was restored to working order and is now run by the National Trust.

My father and his friends used Youth Hostels as they cycled around the country, so I am almost certain that he stayed here on his journey through Winchester. The National Trust web page for the mill has some accounts from people who stayed at the youth hostel during the 1940s – the link to the page is here.

The same view today – not much has changed.

In the following photo, the bridge is from where the above photos were taken. The mill is the building behind the bridge so this is a short distance further along the River Itchen looking back at the mill.

The same view today.

A short distance from the mill is the Old Chesil Rectory. Originally built by a wealthy Winchester merchant, the building was constructed between 1425 and 1450 and in 1949 was a restaurant serving lunch and tea.

The building is still a restaurant, but has dropped the “old” and is now simply The Chesil Rectory and appears to be very popular as we tried to get a table on Saturday lunchtime but they were fully booked for the whole weekend.

The front of the building looks much the same, however in 1949 the side of the building running to the right appears to have been all brick, presumably covering the original wall that has now been exposed.

As with much of Winchester outside of the pedestrianised High Street there is considerable traffic and I had to wait several minutes to get a clear shot of the front of the Chesil Rectory. It must have been a much more enjoyable experience to explore towns and cities without the high levels of traffic that we have today.

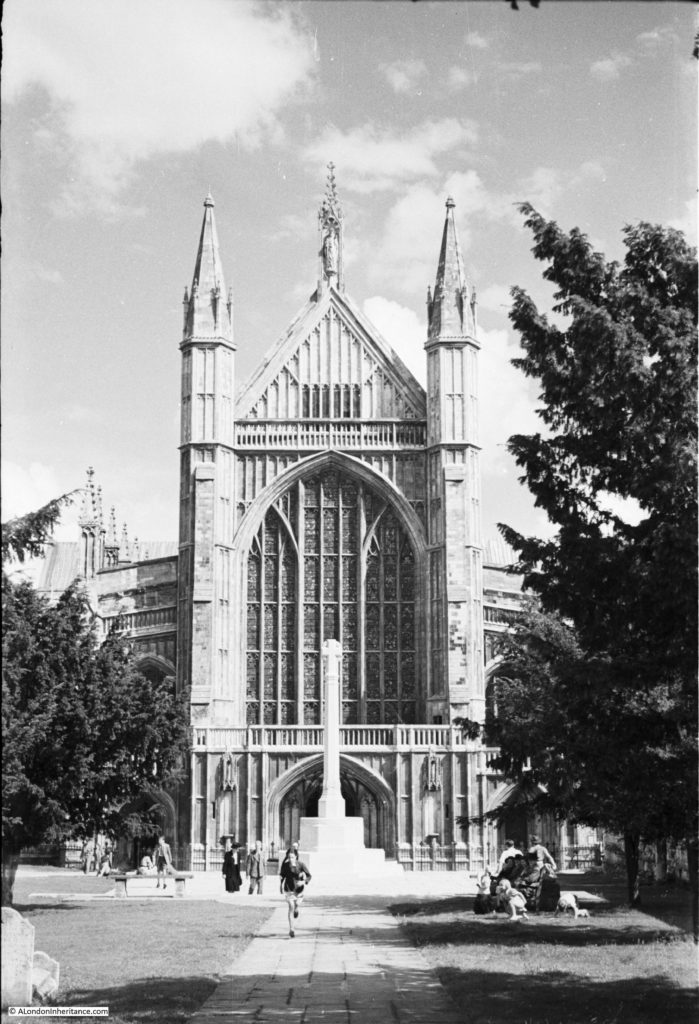

The next stop is back up the High Street where we can turn off one of a number of side streets to reach the Cathedral. This was the view looking down towards the main entrance with the war memorial in the foreground in 1949.

The same view today – the trees on either side have grown considerably in the 67 years between the two photos.

Walking down towards the war memorial I moved from under the trees to get this view of the Cathedral. The large west window was destroyed by Parliamentary soldiers in the Civil War, but later rebuilt using the shattered glass collected from around the Cathedral.

The church in Winchester has a long history. the first church (the Old Minster) was built by King Cenwalh in 648 with building of the Norman Cathedral that forms the core of the current building starting in 1079 with the Old Minster being demolished in 1093 when the new cathedral was consecrated. The Cathedral has been through a number of changes, additional development, damage during both the dissolution and the Civil War and major work on the foundations to prevent serious damage to the fabric of the building in the early 20th century.

On entering the cathedral today, the first view is of the nave:

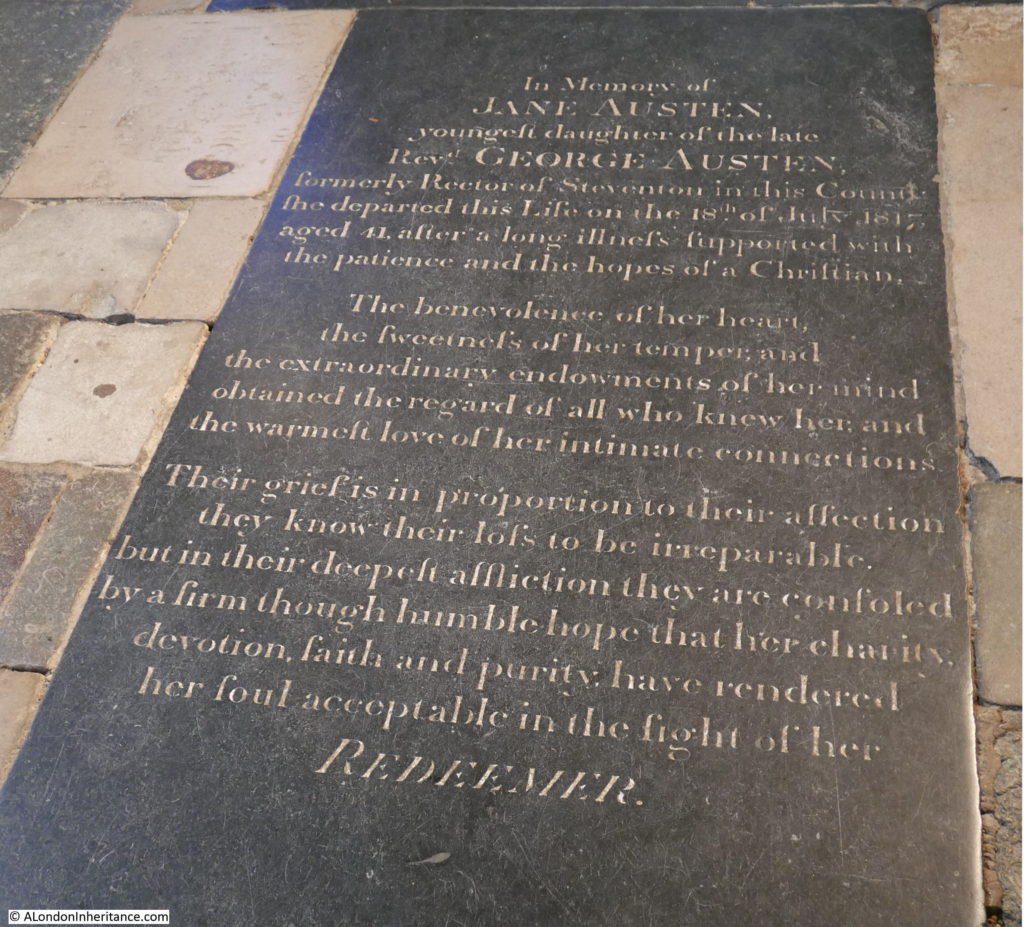

To the left of the nave is the grave of Jane Austen who died in Winchester in 1817. The gravestone makes no mention of her achievements as an author apart from the reference to “the extraordinary achievements of her mind”.

Perhaps to rectify this omission, a memorial was erected in 1900 and paid for by public subscription – the text starts with “known to many by her writings”.

Walking round Winchester Cathedral, there are so many survivals from the Cathedral’s long history. Here, the mid 12th century font made from black Tournai marble:

The crypt of the Cathedral has an Anthony Gormley sculpture of a life-size figure of a man contemplating water held in his cupped hands. The crypt is from the earliest phase of the Cathedral having been built in the 11th century. The crypt also suffers from the geological conditions of the ground in the centre of Winchester as during periods of heavy rain the crypt will flood, often up to the knees of the statue. The ground water under and around the Cathedral caused considerable problems during the early part of the 20th century.

It is possible to see the colour with which churches were decorated prior to the dissolution during Henry VIII’s reign. Some of the original 12th century wall paintings and 13th century painting on the ceiling remains:

The Great Screen built between 1470 and 1476. The statues across the screen are late 19th century replacements as the originals were destroyed in 1538 during the dissolution.

As with so many public buildings of this age, many of the monuments, walls and pillars are covered in early graffiti. I wonder who MC was and what he was doing in the Cathedral in 1624?

Winchester Cathedral also has the largest and oldest area of floor tiling to survive in England, mainly from the 13th century. Walk on these and think about who could have walked the same way in the previous 800 years.

There is a most unusual monument in the Cathedral, perhaps the last place you would expect to find a diving helmet. This is the memorial to the diver William Walker who is honoured for saving the Cathedral at the start of the 20th century when It was found that the wooden foundations of the Cathedral were rotting and the building was starting to subside.

The centre of Winchester, including the Cathedral is within the valley of the River Itchen as we saw earlier in this post. The Cathedral is built on a peaty soil and there is a very high water table (as mentioned earlier which also causes the crypt to flood).

The plan to stop the subsidence was to dig down and fill trenches under the walls with concrete, however due to the high level of ground water, as the workmen dug down, the trenches filled with water. The only way to attempt the work was to call in a deep-sea diver who could excavate the trenches and fill with concrete. This is where William Walker, an experienced deep-sea diver from Portsmouth Dockyard was called in.

Walker worked for 5 years in very difficult conditions, often at depths of up to 20ft and with limited visibility due to the mix of water and peat. When all the trenches had been excavated and filled with concrete, the water could be pumped out and the rest of the workmen could fill with concrete bags, concrete blocks and bricks.

The work was completed in 1911 and the Cathedral was saved, mainly due to the efforts of William Walker. He would die in 1918 due to the flu epidemic that spread through the country, however he is remembered by this very fitting memorial in the Cathedral that he played such a crucial role in protecting.

There are so many graves and tombs across the Cathedral of significant age. This one from the 12th century which may contain the remains of Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester from 1129 to 1171. The use of “may” in the information panel is an indication of the problem of really knowing the history of so many tombs in a building of this age and history.

Leaving the Cathedral, I found the following whilst walking past the Guildhall. I have not seen such instruments and inscriptions before mounted in such a position. The latitude and longitude are given and below the window with the barograph the inscription reads that in Winchester real noon is 5 minutes and 16 seconds later than at Greenwich – an indication that as you move further west from the Greenwich Meridian, the sun is directly over head later as you travel further west. Below the reference to real noon is information that the compass points slightly west of north and at the top along the greenish coloured stone is the height above sea level.

Instruments in the windows provide the temperature, wind speed and direction and the barograph records the pressure. The reference to the compass points and the magnetic deviation states this was in 1954 so this installation may well date from then. No idea why it is here, but I really like this.

That is the end of my brief visit to Winchester and Stonehenge in 1949 and 2016 – as usual I left Winchester with the feeling that I had only just started to understand the city and its history. Winchester is back on the list for a future visit.

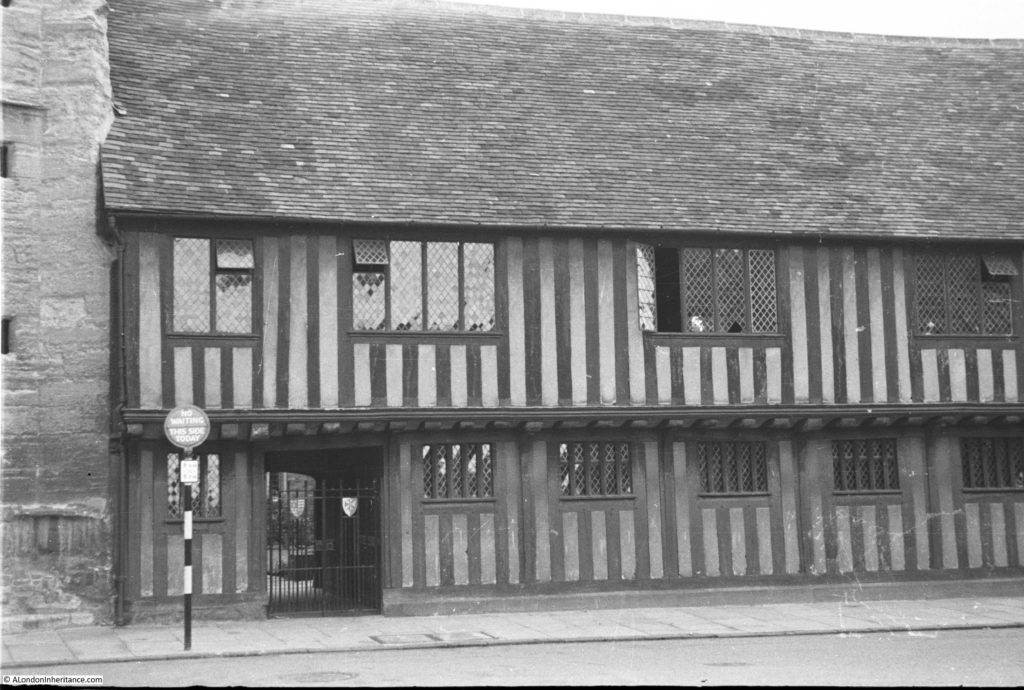

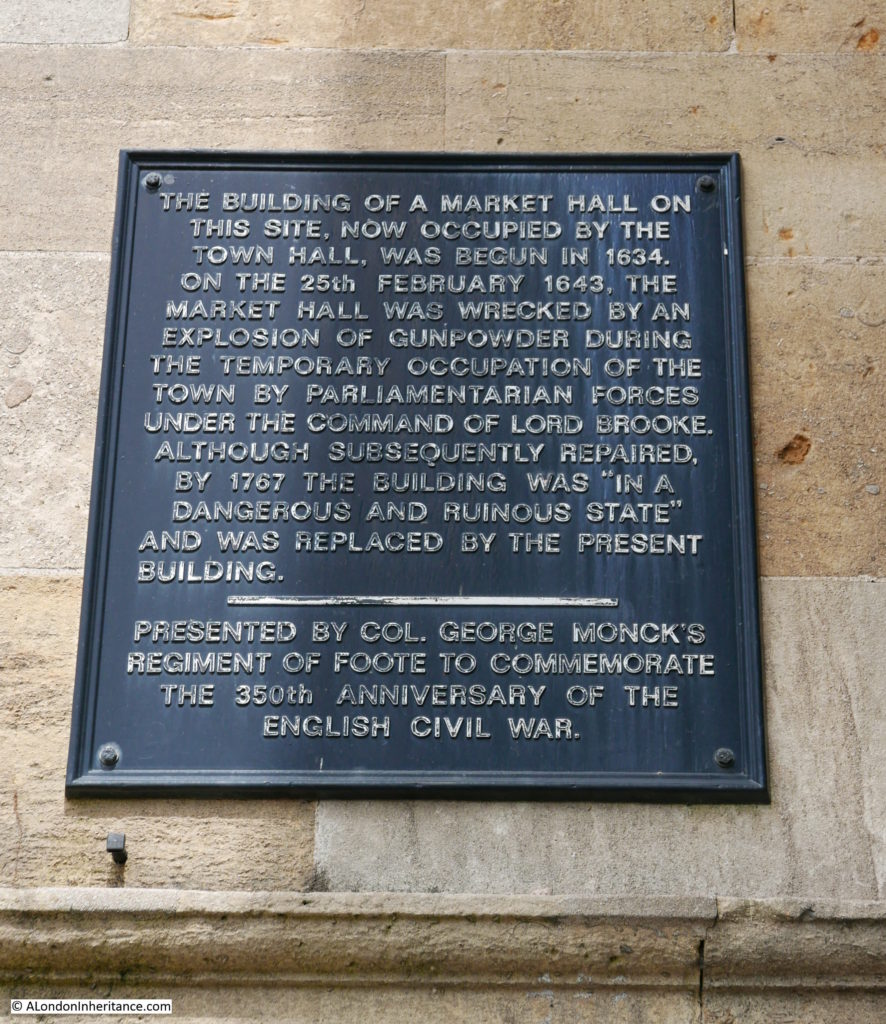

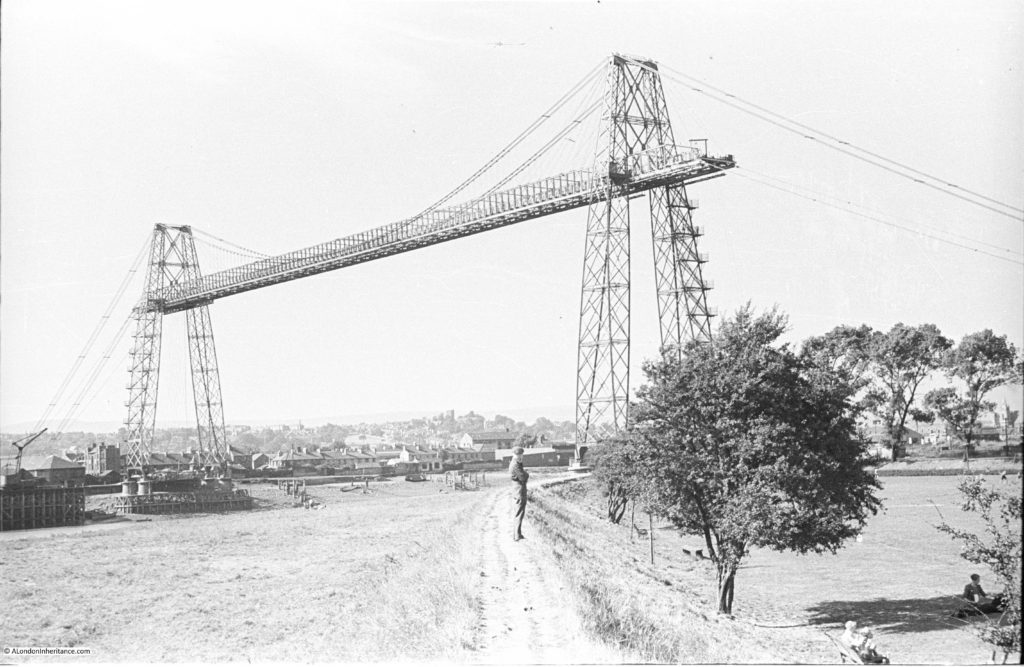

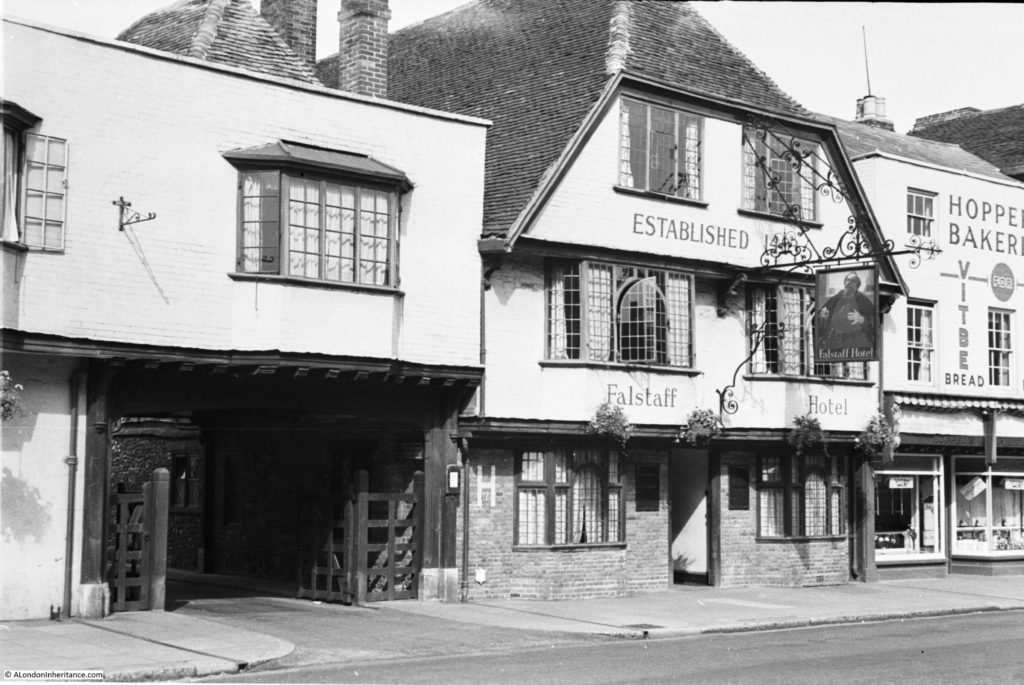

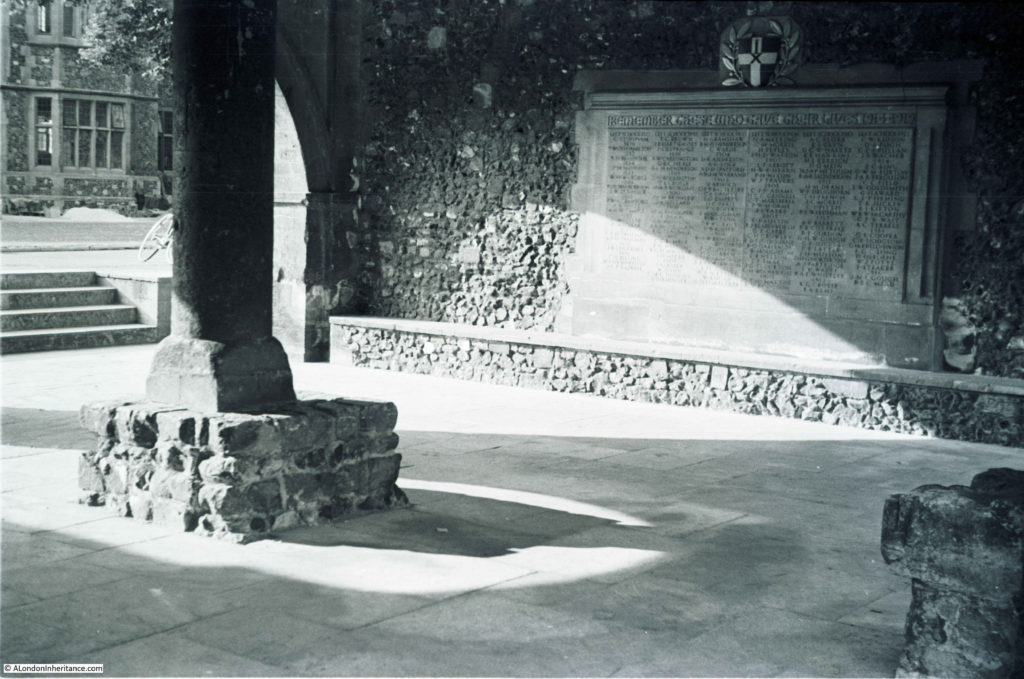

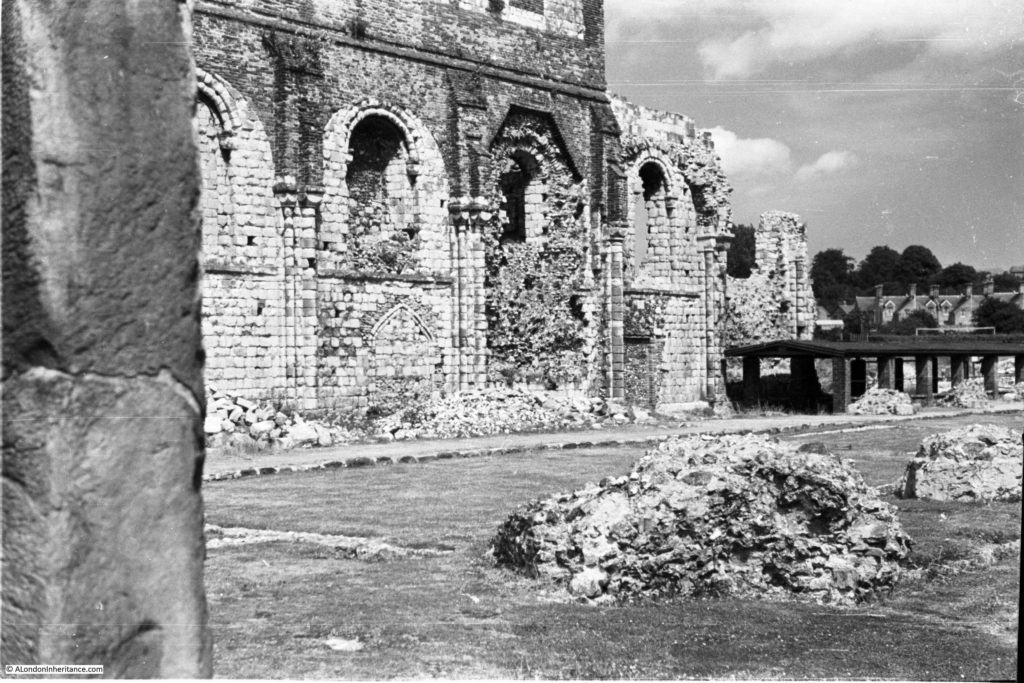

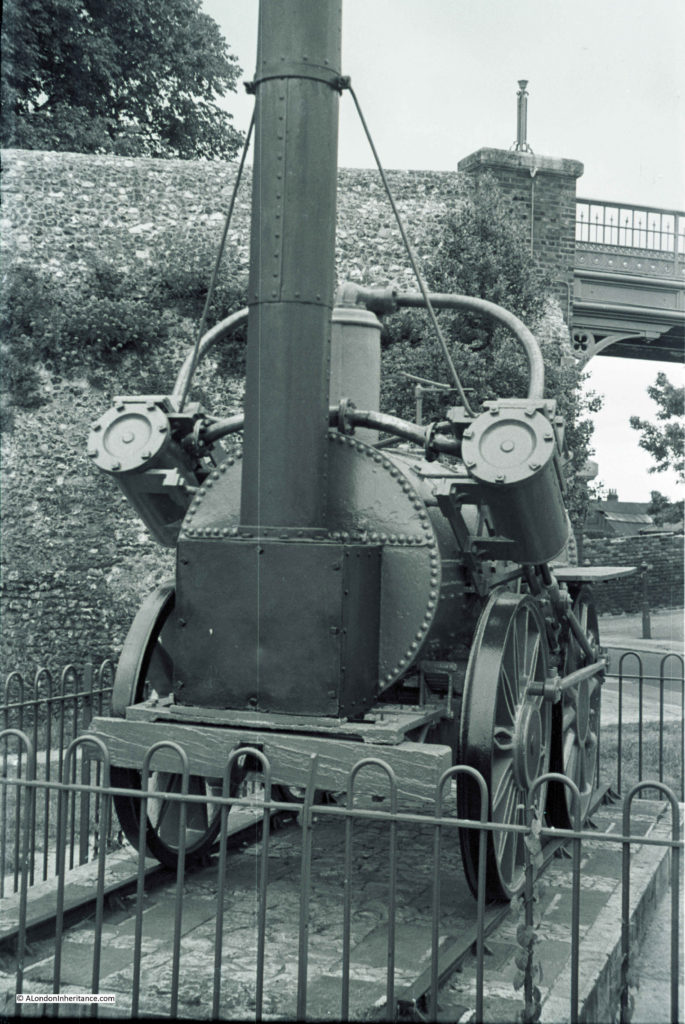

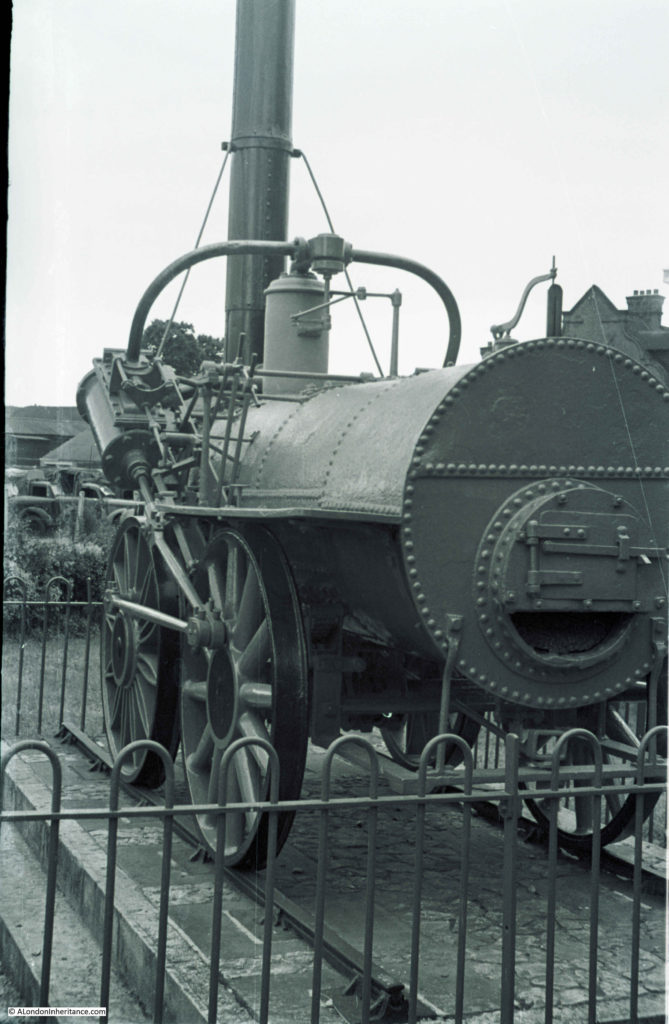

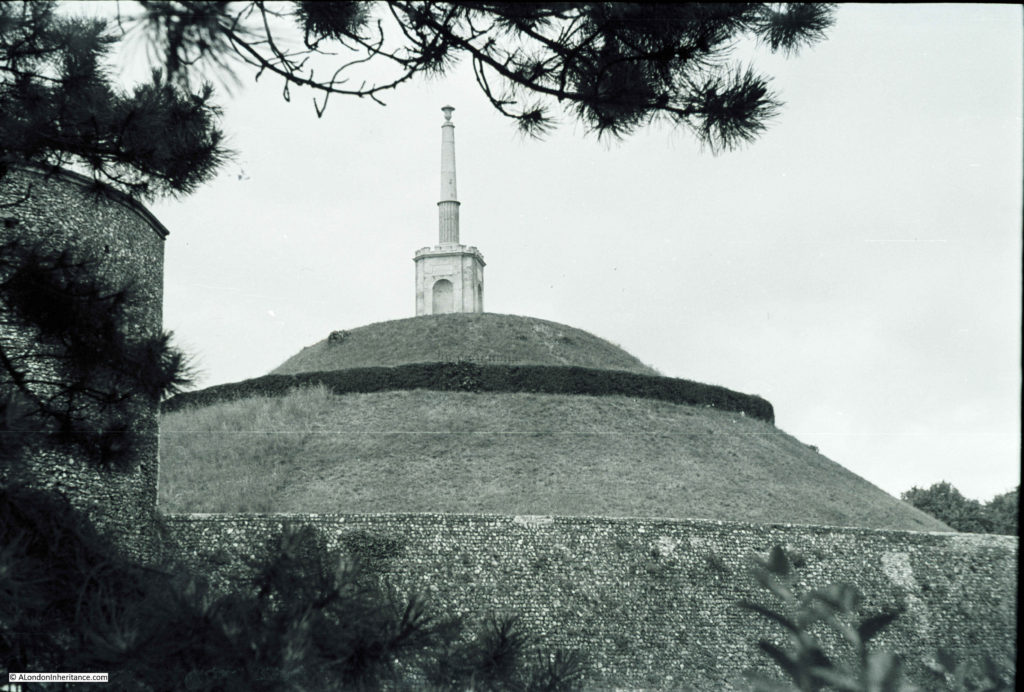

To end the post, here are two photos that are on the same strip of negatives as some of the Winchester photos and which I have been unable to locate. I am really grateful to Nick who identified the unknown location at the end of last week’s post as the Almonry Museum at Evesham, Worcestershire.

The first photo appears to be the entrance to a town / village church. The building on the left appears to be a Tea Rooms judging by the signs. The sign in the shop window on the right is advertising a Cricket Match and Grand Dance, but the rest of the text in not readable.

I am really not sure what this building is, but the tall chimney like structure is very distinctive.

Any help with identifying the above would be really appreciated.