If you walk from Sloane Square, along the King’s Road, pass the Saatchi Gallery on the left and a short distance further on the right will be Tryon Street, a very narrow Chelsea street leading from the King’s Road. No entry signs indicate that you cannot drive directly into the street as it is a one way street with traffic entering from Elystan Place to the north.

Walking from the King’s Road reveals a street that has hardly changed in 70 years. This is my father’s photo:

And my 2018 photo taken on a very sunny September afternoon:

I took the 2018 photo in Black & White as I suspect using colour artificially over emphasizes the changes in a scene, and in Tryon Street there has been very little change in 70 years.

The bollards have been changed, however a continuous line of bollards still runs the length of the street. There have been some cosmetic changes to the buildings, with a bit more structural change in the buildings nearest the camera. The road has been resurfaced, yellow lines have been added and the same metal chamber cover is in the same place in the middle of the road.

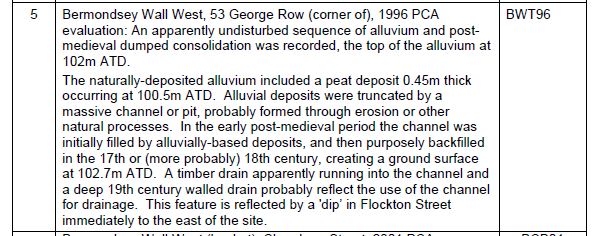

I am not sure why my father took the photo of Tryon Street. There is no obvious feature in the photo. i suspect the bollards had something to do with the decision to photograph the street as the line of bollards leading of to the end of the street enhances the composition of the photo.

I could not find that much information about Tryon Street. It is only a short street, the above photos show the full length of the street and it was only named Tryon Street in 1913, the street was originally part of the much longer Keppel Street, however the origin of the name is fascinating.

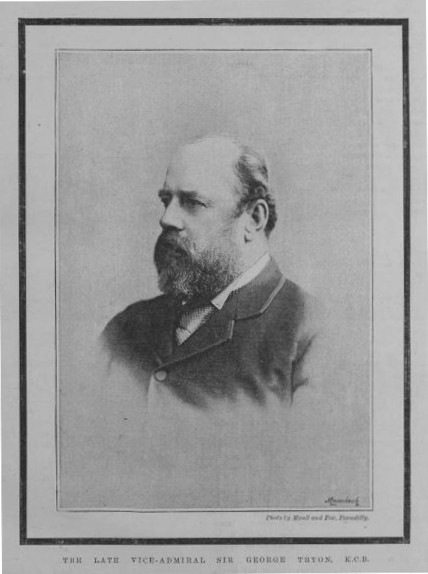

Tryon Street was named after Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon who died when his ship sunk in the Mediterranean in 1893. The name of Tryon Street recalls a major naval tragedy.

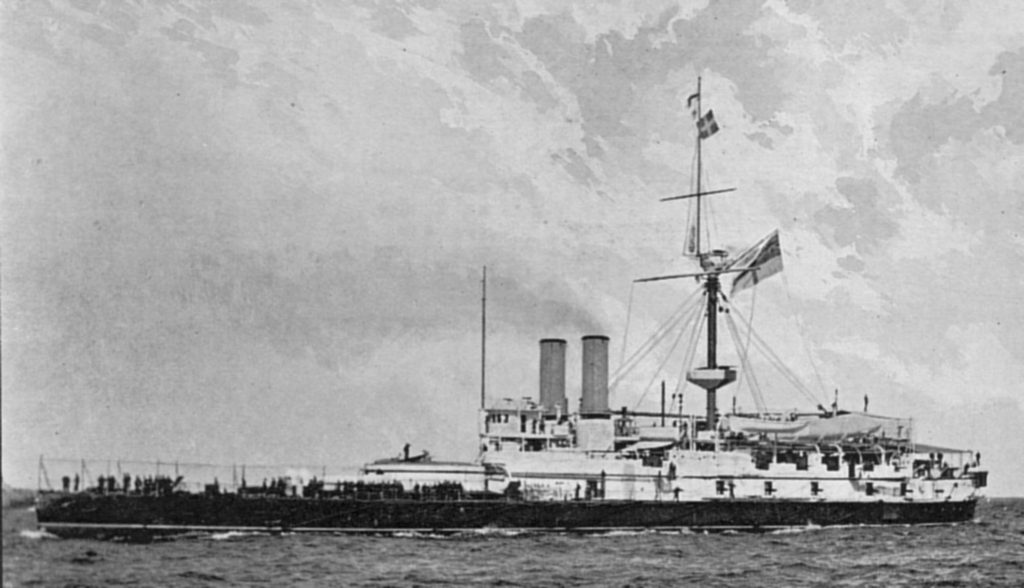

Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon was the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet and leading the fleet in his ship Victoria. The fleet was to move from off the coast of Syria and make their way to new anchor positions off the Lebanon at Tripoli. The London Evening Standard on the 4th July 1893 details the circumstances of Tryon’s death and the sinking of the Victoria in a letter from “a Senior Office of the Fleet”:

“When ships are in columns of divisions, as we were, they ought to be twice the number of cables apart as there are ships in the longest line or column. We had six ships in the first division, and five in the second division- i.e. we ought to have really twelve cables apart (2400 yards); but we were only six cables (1200 yards). The diameter that the slowest ship is supposed to take in turning 16 points or right round is 800 yards. therefore two ships would occupy 1600 yards. We were coming up from Beyrout about six miles from the shore, and were in two divisions, but only six cables (1200 yards) apart.

The Admiral wanted to anchor the Fleet in line abreast, one division behind the other, to do which he had to re-form the fleet first, by turning the ships right round. He could have done two things, either turning each division outwards, or each inwards. He, for some reason, made the signal to turn inwards, namely, each ship in the division to turn in succession inwards on arriving where he turned. The two ships turned inwards, and the Camperdown closed watertight doors, seeing it impossible to avoid a collision. She struck the Victoria nearly at right angles, both ships going eight knots, just before the fore turret on the starboard side.

The Victoria had a fearful hole in her side, and as she heeled, her turrets and guns may have got loose and helped to turn her. She first seemed to have her bows under water, but made the signal ‘Negative sending boats’ and a semaphore, ‘Do not send boats but have them ready’. the next thing that I saw was that she began to heel over to starboard, and then more, until I could see her port screw going round out of water, it was a horrible sight. Next she seemed to make a plunge forward to starboard, and suddenly went right over, and we saw for a brief moment a most sickening sight, which I am sure, filled us all with awe – the enormous bottom upwards and both screws going round. I can see it now. In fact, one can never forget it. Then she sank and all was still. Of course, all boats in the Fleet were away as soon as we saw her with such a heel, and remained there until dark. However it was soon known that our Commander in Chief was gone. The poor engineers and the stokers in the engine-room and the stoke-hole ! Theirs must have been an awful death – too awful to think of. Thank God though that their end was not a slow one, for I think she blew up, as a few seconds after a huge volume of smoke arose to the surface.

One of the ship’s officers told me that there was hardly time to close the water-tight door, and when he tried to get below, he was stopped by the volume of water, so he began to get the boats out. But soon it was a case of ‘all hands for themselves’. I believe the Admiral was last seen holding on to the rails of the chart-house forward, and would not leave the ship. poor fellow, I suppose at that last minute, he perhaps realised the mistake he had made and thought it best to show an example to duty by stopping at his post, although he told those around him to save themselves, for which I hope the country will forgive him. None of us can understand why the signal was made, although Markham hesitated in obeying it, and why the latter, fully knowing and realising the danger of the manoeuvre, ever carried it out.”

As well as Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, 22 officers and 336 men died in the sinking of the Victoria, although some reports put the number of casualties as high as 422. Of the casualties, 19 were were recorded as ‘boys’.

The wreck of the Victoria was considered to be in too deep water to attempt any recovery of bodies, and HMS Victoria still sits at the bottom of the Mediterranean near Tripoli, Lebanon.

The Illustrated London News carried a number of illustrations of the tragedy, including the following illustration showing the Victoria starting to turn over, with one of the screws already out of the water.

HMS Victoria before the tragedy:

Image from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Victoria_(1887).jpg

I cannot find any association between Sir George Tryon and the street that now has his name, however he did have a London house at Eaton Place, not that far away, on the other side of Sloane Square, where his wife was in residence at the time of the disaster.

Portrait of Sir George Tryon from the many newspaper accounts of the disaster:

Whilst Tryon Street may appear rather ordinary, the origin of the name is anything but.

Walking down Tryon Street, there are some interesting buildings. A short distance along on the right is this building. In the original photo, just the entrance on the left is visible.

Further along, on one of the terrace houses on the left is a rather ornate plaque. Chelsea had a a long association with pottery so perhaps the plaque is from, or has some relevance to the Chelsea potteries.

At the end of the street is a typical Victorian corner pub – the Queen’s Head.

The pub closed on the 7th September 2016 and has been waiting for planning permission to be granted for changes. Originally a full conversion to residential was proposed, however the latest planning request is for residential on the first and second floors, and extension to the roof with conversion of the extension to the left of the pub also to residential.

The intention is that the pub will reopen on the ground floor and basement as a pub and restaurant.

The rather strange looking extension on the left of the pub is an early 20th century conversion, where the original house that was part of the 19th century terrace that runs along Tryon Street, was demolished and the pub extension built. It was used as a lounge bar to the pub.

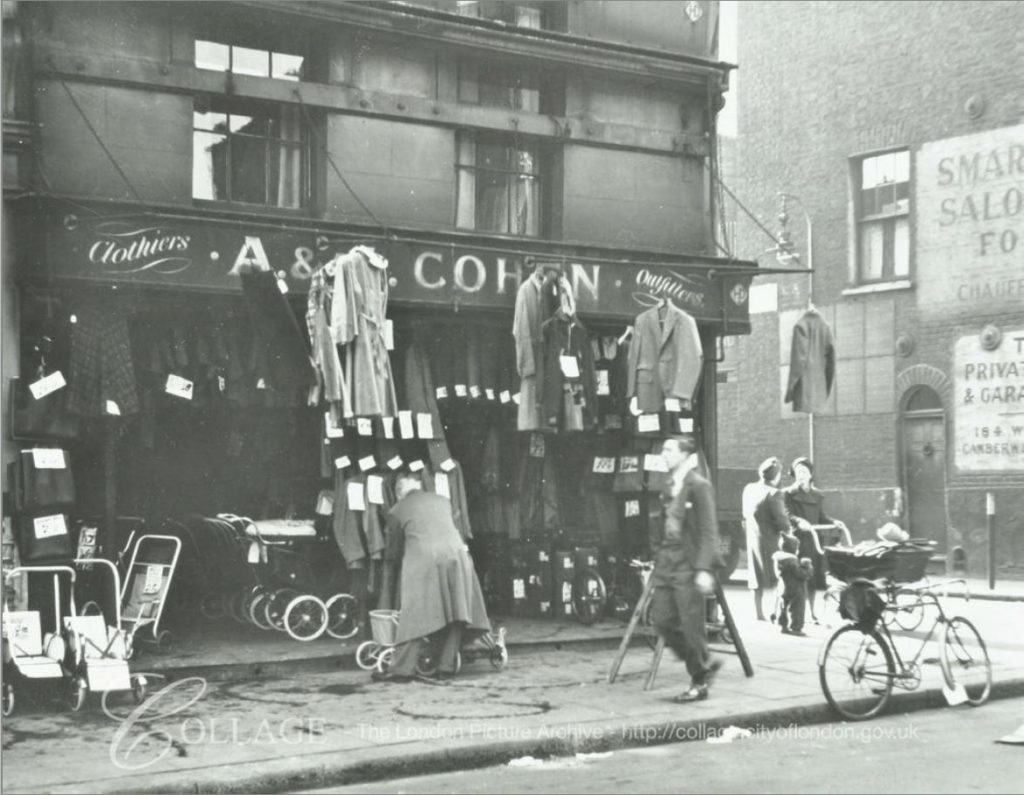

I cut an extract from my father’s original photo to show the detail of the pub as it was.

The pub sold Barclays Beers. There is what appears to be a pram parked outside the pub.

The Queen’s Head is a very distinctive feature on the corner of Tryon Street and Elystan Place. The building is higher than the terraces on either side helping the pub to stand out.

Decorative feature of the Queen’s Head on the first floor of the pub facing onto Tryon Street.

The Queen’s Head facade facing Elystan Place.

In the short time I was in Tryon Place, it seemed very quiet, very different to the King’s Road at the end of the street. There was no through traffic and just the occasional walker using the street as a cut through to somewhere else.

A search through newspapers revealed the normal adverts of goods for sale, situations vacant, tragedy and strangeness that can be found in any London street over the years.

On the 2nd of August 1940, Mr William Hendra aged 70 dropped dead in Tryon Street whilst on his way to work. He had been a foreman painter for 46 years and left a widow, fours sons and three daughters.

In October 1952, a man was arrested at 4:40 am “because he insisted on standing in the middle of Tryon Street, Chelsea and playing a trumpet. David Patrick (aged 22 and described as of no occupation), of Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, was at West London, fined £1 on a charge of insulting behavior. He was ordered to forfeit 10s of his bail because he arrived late.”

In February 1940, the secretary of the Ye Old Bell Loan Club and the Queen’s Head Loan Club, both of the Queen’s Head pub, Tryon Street was sent to prison for a month after the loss of £70. In what must have been a very common situation, the secretary was out of work and having to support five children on 39s a week unemployment benefit. The magistrate appears to have been sympathetic as he said “I am exceedingly sorry to see you in the position you are now. It is impossible to pass over an offence of this sort. I don’t say you started taking money intending not to repay, but it is gross carelessness on your part to take £70 without knowing what had become of it. Unless you had a good character I would certainly have given you a long sentence. As it is, go to prison for a month and think yourself exceedingly fortunate”.

Looking back down Tryon Street towards King’s Road:

It is always interesting to look at the pavement when walking London’s streets, as well as the buildings. There are plenty of covers to coal holes along the pavement. This one is marked as Green & London – Chelsea, London, SW.

The cover was purchased locally as Green and London were an ironmongers located at 121 King’s Road.

Tryon Street has changed very little over the last 70 years. A short street that most people appear to use as a cut through to and from the King’s Road, however it is a street with a name that recalls a naval tragedy of the late 19th century.

It will be good to see the Queen’s Head restored and reopened as a pub. There are too many lost pubs in London so retaining this fine Victorian example will be one small victory.