Firstly, thanks for the comments on last week’s post on the Greenwich foot tunnel. Some brilliant personal memories of the tunnel, and the important part it has played in the life of those on either side of the river.

Today is one of those Sunday’s where I ran out of time to research and complete the planned post, so the location in east London will have to wait, and for this week, a photographic tour of London in the first decades of the 20th century from the late 1920s book Wonderful London.

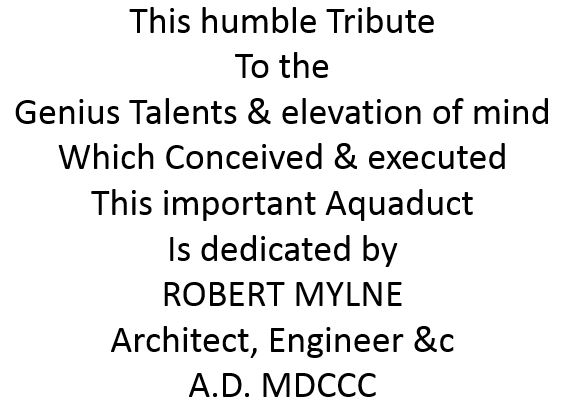

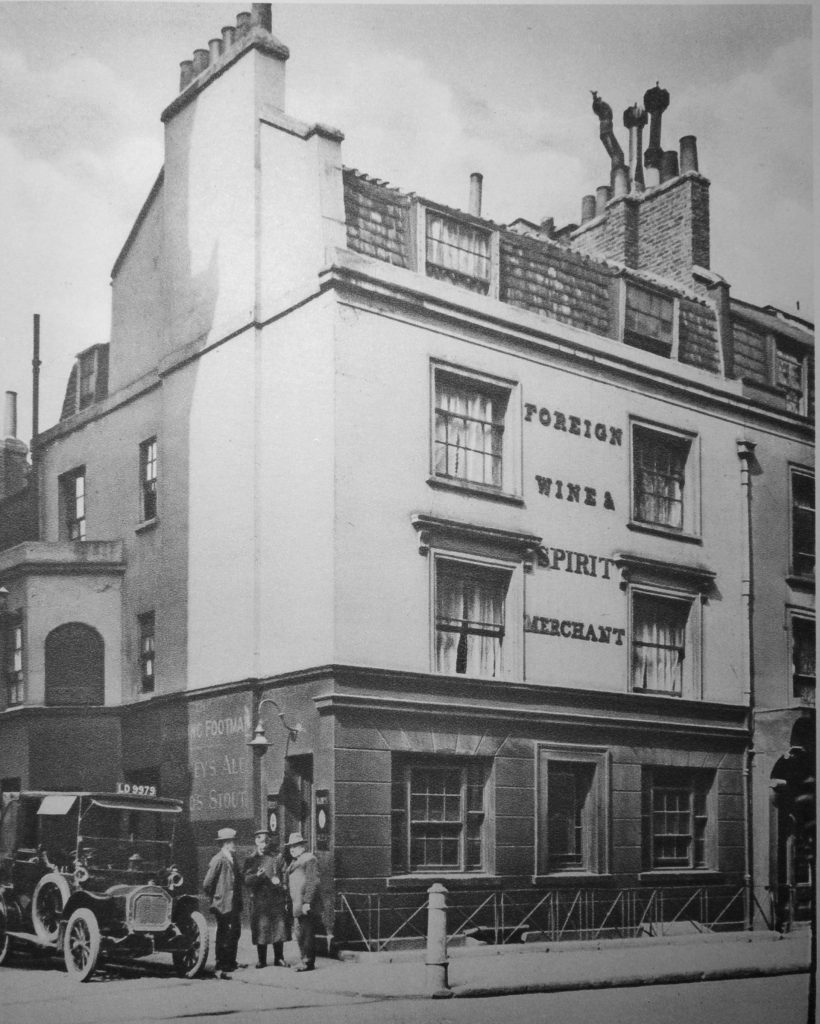

Always good to start with a tour of some pubs, and this is the Running Footman, on the corner of Charles Street and Hays Mews, near Berkeley Square.

The building in the view above would not last much longer. originally dating from 1749, the pub was rebuilt in the 1930s using the type of brick construction typical of many pubs of the 1920s and 30s.

Wonderful London described the source of the name as “named after that special kind of servant whose duty it was to run before the crawling family coach, help it out of ruts, warn toll-keepers, and clear the way generally. He wore a livery and usually carried a cane”.

The 1930s pub is still open, but with a shorter name of just The Footman.

Another pub is the Grenadier in Wilton Mews, near Upper Belgrave Street:

Wonderful London expects that “At any moment it would seem that an ostler with striped waistcoat and straw in mouth might kick open the door and walk out of the place. Just past the wooden gate by the little boy is a doorway in the wall leading to Philips Terrace”.

I took a very similar photo back around 1972. I had been given a birthday present of a book about haunted London and the Grenadier was described as one of the most haunted pubs so it was on the agenda for a family walk where I used my Kodak Instamatic 126 camera. I still have to find and scan the negative.

I did revisit the pub a couple of years ago when writing about Old Barrack Yard and the Chinese Collection. The Grenadier looks much the same, however the tree which had not yet been planted when the Wonderful London photo was taken, now obscures much of the the early 20th century view.

That’s two pubs which can still be found today, and to add a third, this is the Bull’s Head at Strand-on-the Green:

The Bull’s Head is in a wonderful location. Facing the River Thames (behind the photographer in the above photo) and next to Kew Railway Bridge. Wonderful London claims the following “An old river tavern, probably built in the 16th century. There is a tradition that Oliver Cromwell, while campaigning in the neighbourhood, held a council of war here. There is also a record that in 1708 a certain John Newall, presumably the landlord, was so unfortunate as to have his malt house burn down. But beyond these slender records the history of the Bull remains obscure”.

The building is Grade II listed, and the pub’s website also mentions the Oliver Cromwell story, along with the statement that the evidence for his stay is disputed. Whether Cromwell visited the Bull’s Head, or not, it is still a pub in a lovely location as Strand-on-the-Green is a brilliant place for a river walk.

The next pub is the Old Doctor Butler’s Head in Mason’s Avenue in the City of London:

I wrote about this pub last year when I walked round all the pubs in the City of London in July 2020. This is the photo of the pub from the post:

Off to Hampstead now to find the Bull and Bush:

My father photographed the Bull and Bush in 1949, when it faced directly on to the road, and you could pull up outside and nip in for a quick drink:

I photographed the pub for a blog post on the Bull and Bush, 70 years after my father had taken the above photo. The building is still much the same, although there is now a pathway and brick wall separating the pub from the road:

All the above pubs are still open, not a bad record considering the rate of closure in recent years, however they were well known pubs in the early 20th century, and 100 years later are still well known and therefore probably profitable.

One pub that did not survive is Jack Straw’s Castle, also in Hampstead:

My father photographed the pub in 1949 after bomb damage had left the building in a very sorry state:

The building was demolished and rebuilt in 1964 as a pub, to a rather striking design by Raymond Erith, however it is no longer a pub, having been converted into apartments and a gym. The building is Grade II listed which has helped to preserve key features of Erith’s design, despite developers trying to push the boundaries of how much they could change.

I wrote about Jack Straw’s Castle here, and this is the view of the 1964 building today:

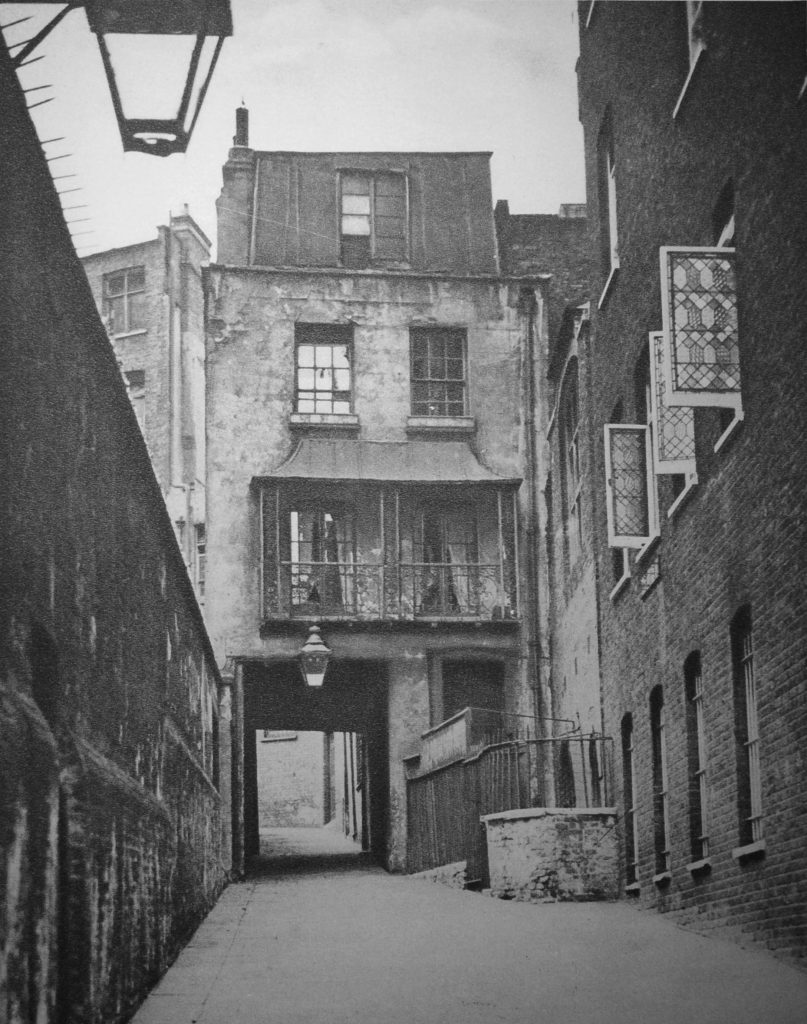

Moving on from London pubs, and in the first years of the 20th century, this is Strand Lane which leads down from the rear of King’s College down to Temple Place.

The view gives the impression of being of the type of slum housing that would be demolished, however the house with the alley has been restored over the years, and still survives, including the ornate iron balcony on the first floor. The high wall on the left, and building on the right also remain, including the iron bars protecting the windows.

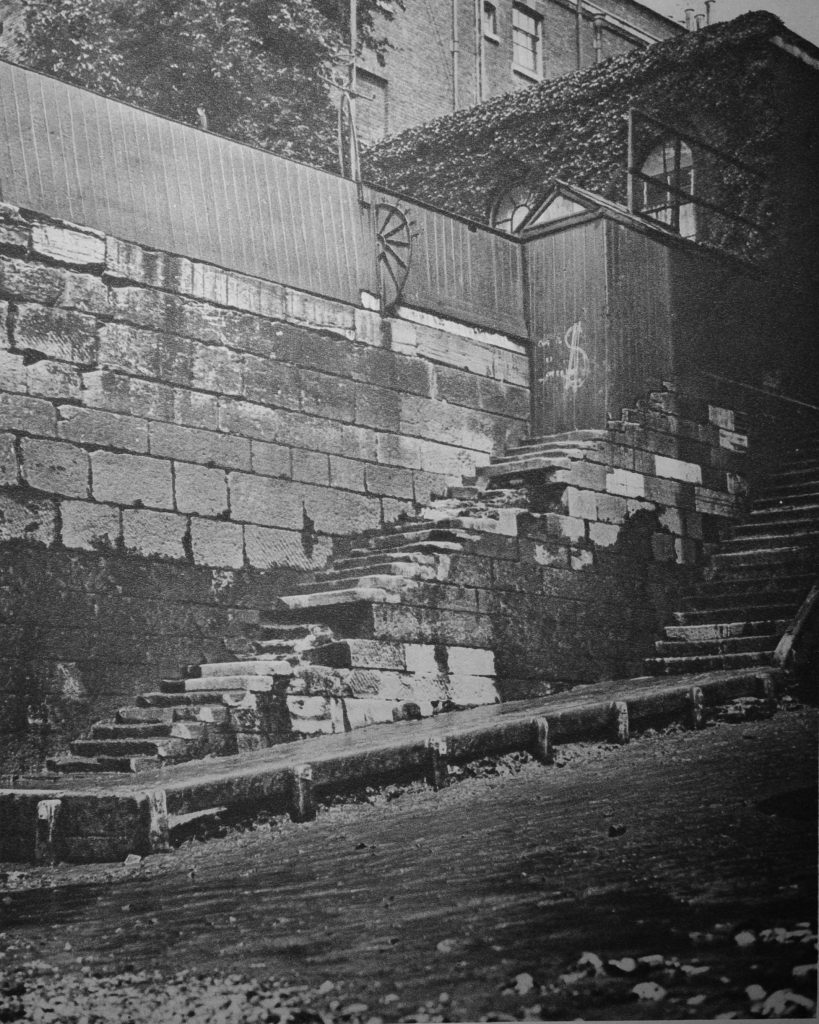

Just proving there are still places in London where you can imagine being back in the 19th century. Another place that has survived are the stairs leading down to the river at Wapping Old Stairs:

Even in the first decades of the 20th century, these stairs were seen as a historical location, as Wonderful London describes “the old riverside annex to the city of the days of the East Indiamen and Nelson’s Ships, has gone and there is little beside these old stairs – leading down to a muddy beach at low tide – left of this, once one of the liveliest spots in the country”.

Much the same description could apply to the stairs today. The following photo is from a post describing the story of these historic river stairs:

The following two photos are titled “Present-day scenes on historic Thames-side sites”

The description from Wonderful London that goes with the two photos is as follows “The upper photograph shows Ratcliffe Cross stairs, an ancient and much used landing place and point of departure of a ferry. There is a tradition that Sir Martin Frobisher took boat here for his ship when starting on his voyage to find the North-West Passage. Ratcliffe Cross is the old name for the thoroughfare leading to this landing stage, whence Butchers Row meets Broad Street, Shadwell and Narrow Street, Limehouse.

Shadwell (lower view) is next to Wapping, and its name is supposedly derived from (St) Chad’s Well. It was once famous for its rope-walks”.

Ratcliffe Cross stairs are sort of still there, as there is still river access where the stairs were located. They are today where Narrow Street curves to a dead end just before the Limehouse Link Tunnel. Ratcliffe Cross stairs are on the list for a future post, as these old river stairs have a really fascinating history.

The Sir Martin Frobisher mentioned as using Ratcliffe Cross Stairs was a 16th century sailor and privateer who made a number of attempts at discovering the north-west passage across the north of Canada from Atlantic to the Pacific. As well as allegedly using the stairs, another connection with London is that he was buried at the church of St Giles, Cripplegate, and is why Frobisher Crescent in the Barbican is so named.

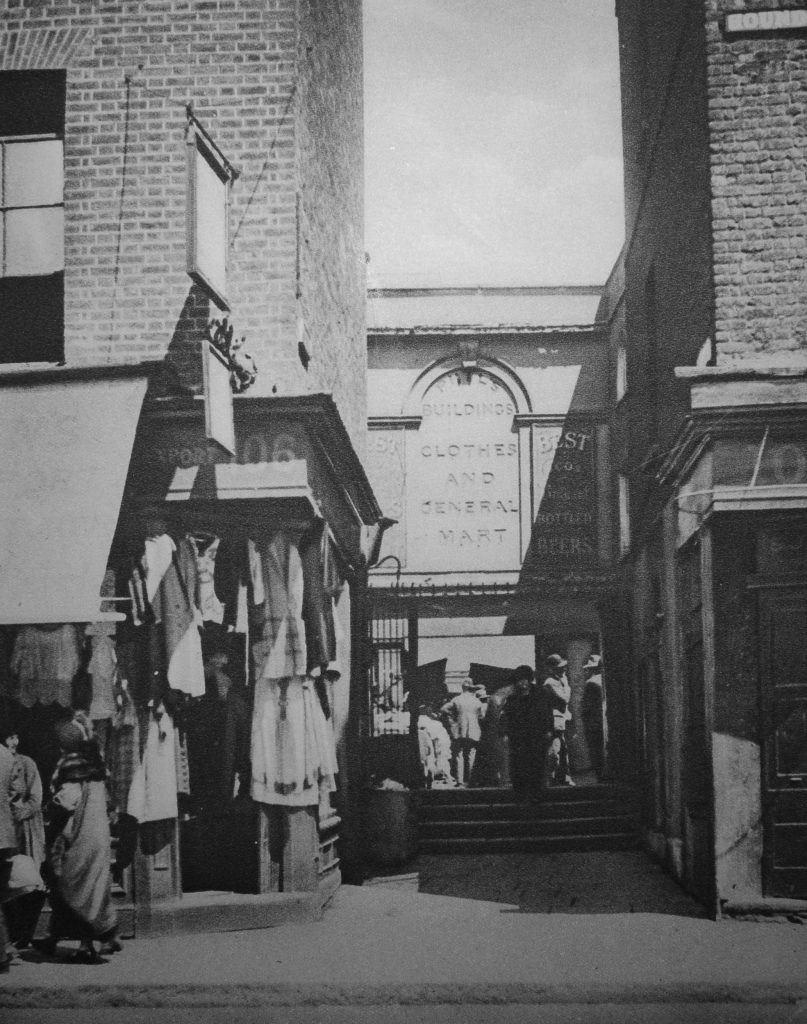

The next photo is in the east of the City where “In Houndsditch, where bargains are driven for inexpensive clothes”:

Houndsditch was the location for shops and a market selling every conceivable item of clothing, both new and secondhand. The name came from the ditch that once surrounded the City wall, and was frequently used as a dump for everything, including dead dogs.

Houndsditch continued discount trading into the 1980s, and if you listened to either Capital Radio or LBC during the late 70s / early 80s there were frequent adverts for the Houndsditch Warehouse where “five floors of bargains can be found at our store”. The street is very different today.

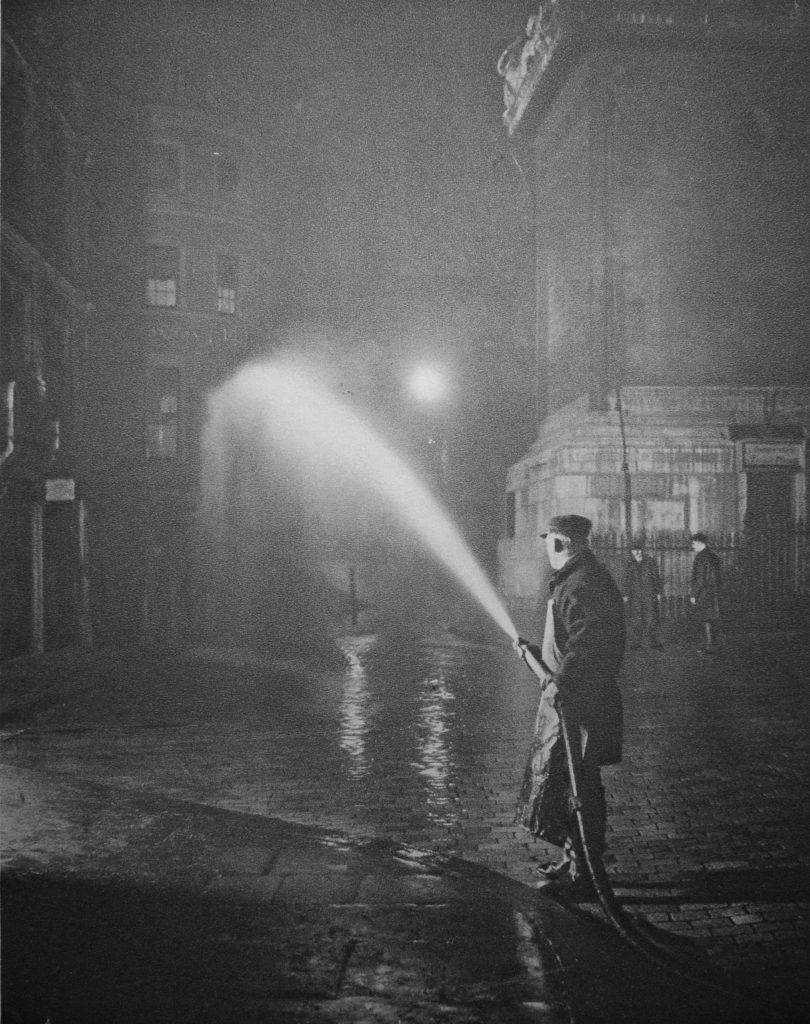

Wonderful London included some night photos of London, including the nightly cleansing of the streets at the base of the Monument, where at “2 a.m. hoses are fitted to hydrants, and men in oilskin aprons wash the day’s filth into the gutter. The neighbourhood of Billingsgate is notoriously unsavoury, but these ministrations keep the fish like smell from becoming too ancient”.

Milk churns being unloaded at Clapham, ready for the city’s tea drinkers:

The following photo is titled “The coffee stall at Hyde Park Corner and some of its various patrons”;

Where “just before ten o’clock every night the coffee stall trundles up to its pitch opposite St George’s Hospital. There it remains till about eight o’clock the next morning, and during that time the men behind the little counter watch, as from a box at the theatre, the hundred different types who act in the nightly drama of London after dark. The medicals student from over the way, the tattered nondescript who hopes for a free coffee, a taxi-driver and his two fares, or perhaps a couple of revelers in fancy dress to whom the visit to the coffee stall is the epilogue to their night’s entertainment; all these types pass during the cold, still hours which the coffee stall serves”.

The following view from Wonderful London is of St Dunstan’s, Fleet Street:

What I like about these photos is not just the overall scene, or the people and vehicles in the streets, but small details like the telegraph poles mounted on the roofs of buildings with telephone cables slung across streets and buildings.

The church is the same today, as are the buildings on either side. I took the following photo for a post about the church a couple of years ago:

In Tower Wharf (the area between the Tower of London and the Thames), Wonderful London has photographed “one of London’s lunch-time gathering grounds”:

The caption to the photo illustrates the popularity and history of the place “Despite the tremendous number and variety of eating places, many hundreds of those who work in the City and its surroundings, prefer , in fine weather, to eat their lunch on a park-seat, or as here, seated on the slippery surface of an old cannon. Tower Wharf, whatever its merits as a restaurant is a fine place from which to view the Tower and also the shipping in the Upper Pool and the opening of Tower Bridge. The wharf was built by Henry III, who also made Traitors Gate. The wharf gave the fortress one more line of protection. On the very ground where the crowd is sitting another London crowd assembled day after day to scream for the trembling Judge Jeffries to be thrown out to them, in quittance for the Bloody Assize”.

Up until the start of the COVID pandemic, the area was usually crowded with tourists rather than City workers having their lunch, and many of the cannons have disappeared. My father photographed the cannons in 1947:

The same view a couple of years ago:

in the background of the Wonderful London photo, ships can be seen passing along the Thames, and the same view could be seen in 1947:

Rather than cargo ships, the view today would be off tourist boats and Thames Clippers.

This was the scene in Carmelite Street, which runs from Tudor Street to the Victoria Embankment. The street is a continuation of a street that runs down from Fleet Street, and was the home of newspapers and printing. The photo is outside Carmelite House and shows rolls of paper arriving and being lifted into the building ready for printing.

Today, the evening papers sold across the streets of London are transported by van, however in the early decades of the 20th century there was a very different method.

The following photo shows newsvendors gathering to collect newspapers. The newsvendor collects a quantity of papers along with a voucher for those papers. The publisher also retains a copy of the voucher.

The newsvendor then distributes the papers among his newsboys, who would then sell them on the streets.

At the end of the day, the newsvendor meets his newsboys, collects unsold copies and the money from sales. The next day he then has to pay the publisher the amount specified on the voucher when he collected the papers.

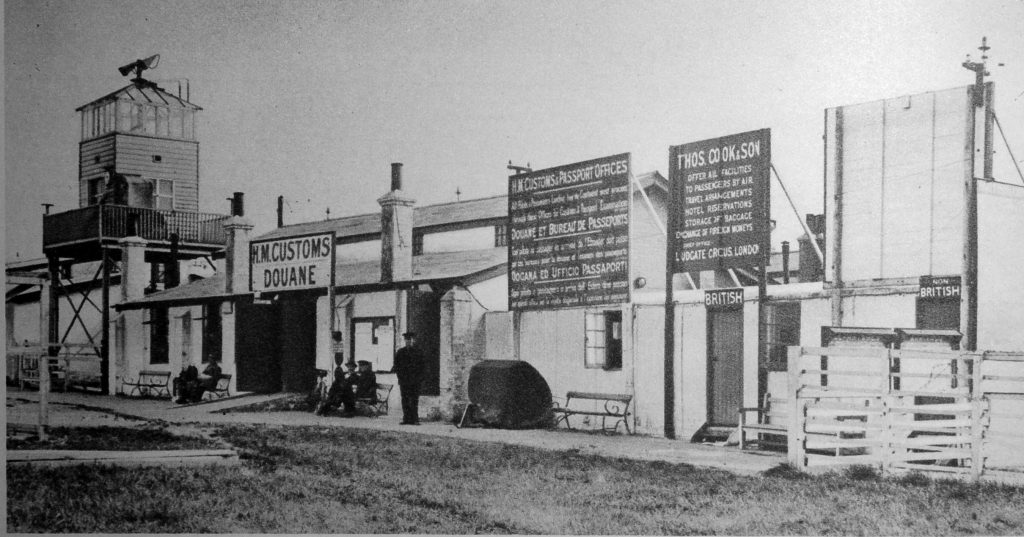

Some of those newspapers could have been transported abroad via the recently opened “Airport of London”, or more popularly known as Croydon Airport.

The following photos shows the arrival facilities for passengers with customs facilities and passport control, with the two doors on the right for “British” or “Non British”:

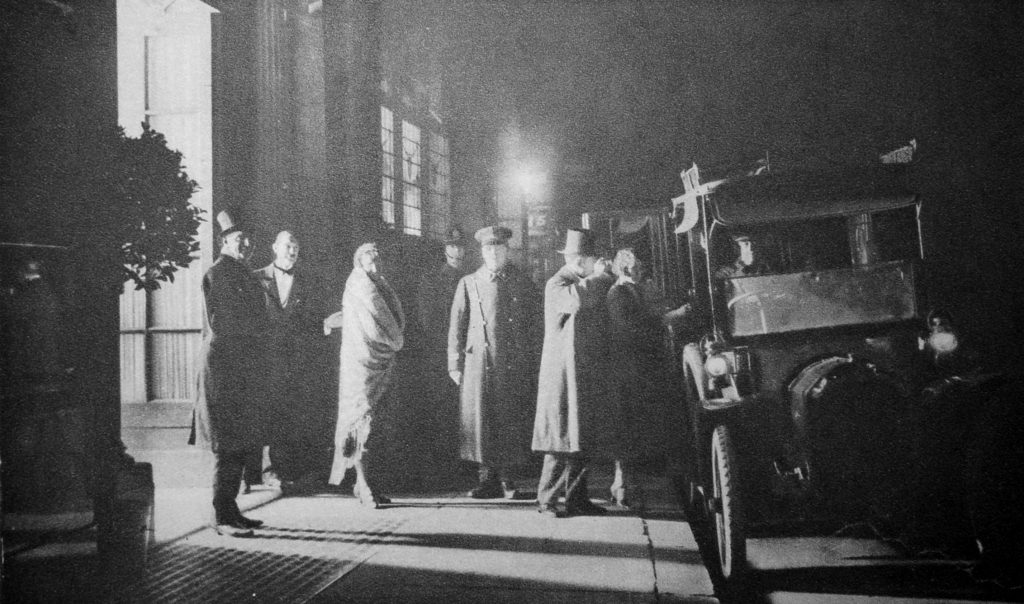

Back to London after dark, and the following photo is showing “An incident at the Yard”:

Apparently a plain clothes officer talking to a Constable at Scotland Yard. It is always difficult to know how many of these old photos were posed or were a real event when the photographer was on site.

The text with the photo does though claim that “The gate is open all night, and anyone in need of police will find ‘The Yard’ ready and waiting”.

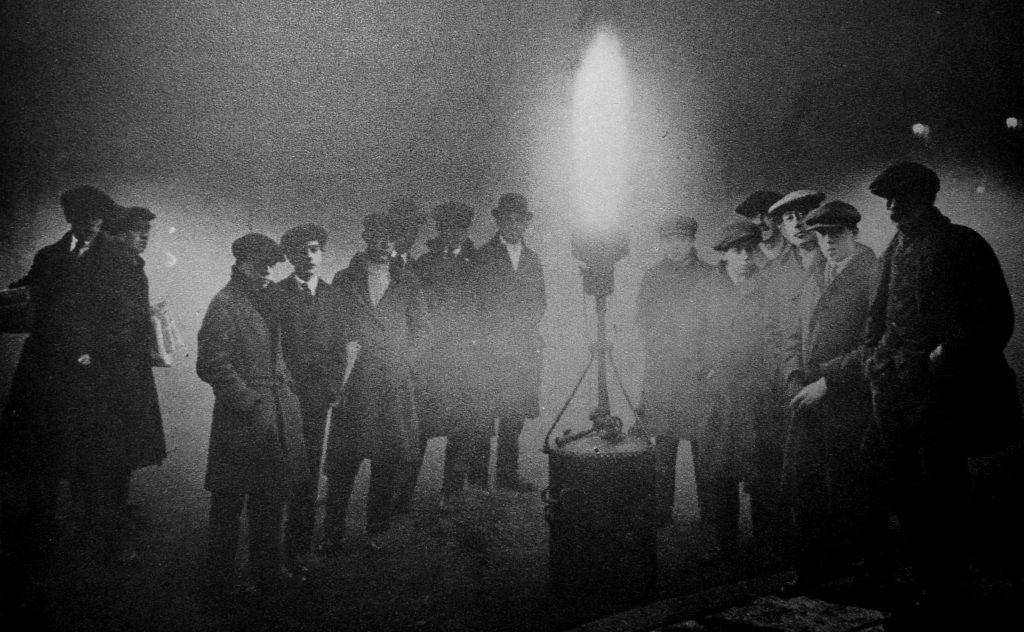

Policing in London during smog conditions must have been rather difficult. Wonderful London describes such an event as “When the minute particles of dust which are always overhanging London become coated with moisture and the temperature falls below what is called the ‘dew-point’, that is, the temperature at which the moisture in the atmosphere condenses, fog blankets the streets”.

When this happened, a number of methods were used to help guide people and traffic around the city, one of which was lighting acetylene flares at key traffic locations as shown in the following photo:

Those who may have needed the help of an acetylene light to navigate the streets of London were those leaving Murray’s Club late at night in Beak Street, Soho:

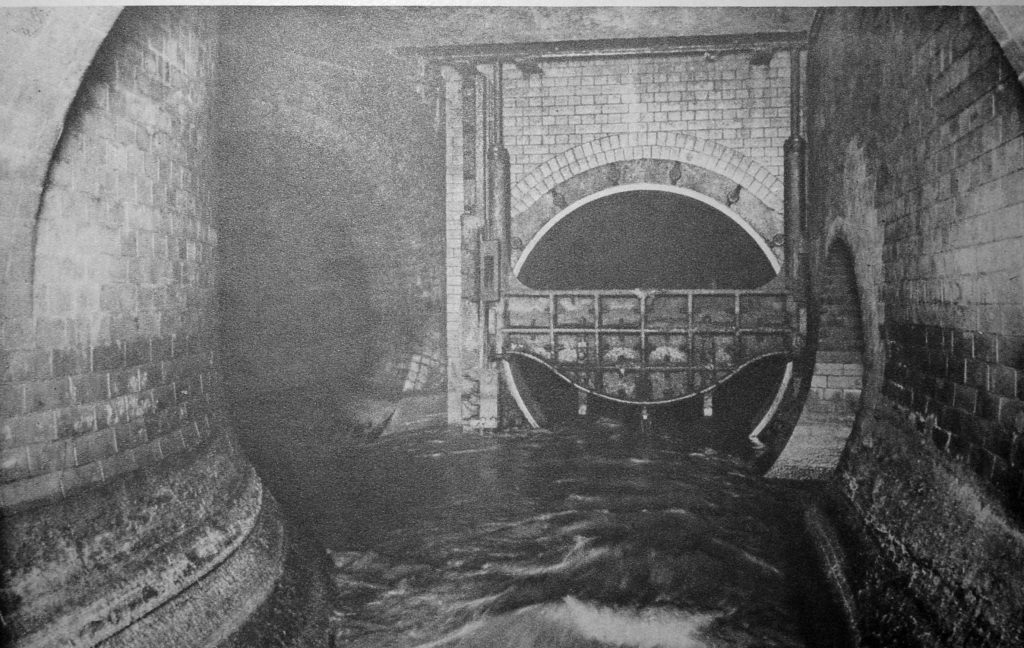

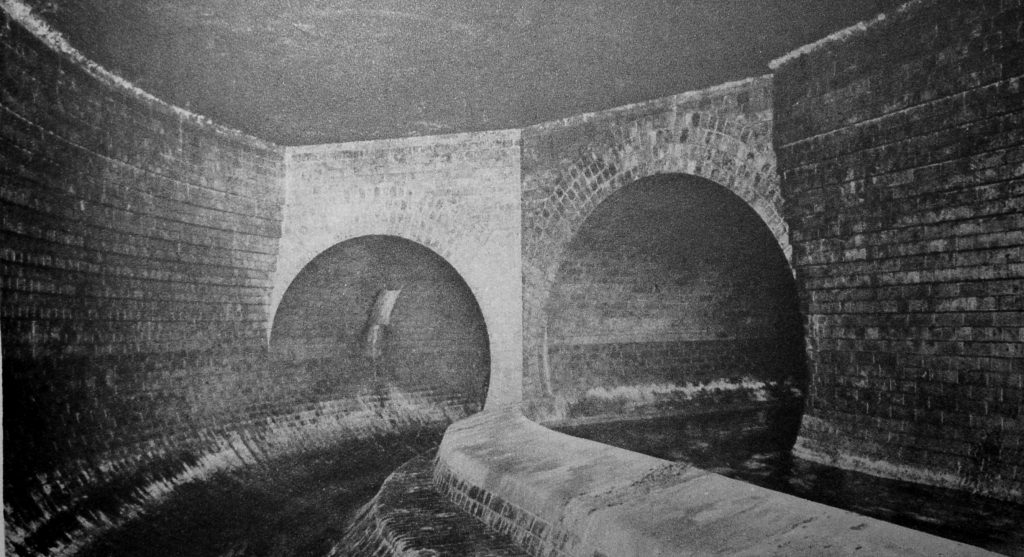

The sewers of London have always been a fascination (at least for me). A parallel world beneath the city’s streets. The following photos show part of the sewer system at Hammersmith. This was the main sewer under Hammersmith Road. Known as the Counters Creek Sewer due to its proximity, and in parts, integration with Counters Creek, the old ditch / stream / sewer / canal that ran from Kensal Green cemetery down to the Thames near the old Lotts Road power station.

The book describes a sewer control system that is basically in use today. Sewers such as the Counters Creek Sewer run north – south, taking water down to interception sewers that run east – west and transport the water for treatment.

When there is too much water for the system to handle, an overflow is needed into the Thames. In the above photo, the overflow sewer is on the right. The device covering part of the sewer entrance is known as a “penstock”, and has been lifted to lower the water level for the photographer.

Normally, this would be lowered to divert water to the tunnel on the left which takes water to the intercepting sewer. When water rises to the top of the penstock, it overflows into the overflow tunnel which then flowed into the river at Chelsea.

The photo below is the other side of the penstock and shows the two tunnels. The penstock has been lowered, and the overflow channel on the left is dry, with water in the Counters Creek sewer on the right.

Over one hundred years later, the construction of the Tideway Tunnel or Super Sewer is intended to end discharges into the Thames by adding additional capacity on the east – west route

What makes Wonderful London so fascinating is the sheer variety of subjects. There are a couple of photos of the remains of the old Merton priory, but a strange photo is of when a workmen digging in allotments near the mill alongside the River Wandle at Merton discovered an 800 year old coffin underneath the cabbages:

No idea if there was any occupant, what happened to the coffin, or whether any further excavations were carried out. Just one of the random photos in the book that came with just a brief description.

The following photo is of Poplar Almshouse with presumably one of the occupants standing outside:

The almshouses were in Bow Lane (which has been renamed as Bazely Street, and runs south from East India Dock Road, and is to the east of All Saints Church).

The almshouses were founded around 1696 when Hester Hawes left six almhouses on the west side of the street for six poor widows, with a monthly allowance of 2s 6d for each widow.

The almshouses were demolished in 1953, so I suspect they were on the site of the flats, just south of the Greenwich Pensioner pub.

Back to the City, and these are members of the Langbourne Club for City Women relaxing on the roof of Fishmongers Hall, or one of the adjacent building, as part of the parapet of London Bridge can be seen in the gaps between the wall.

On the river was a Thames Barge:

The text with the photo comments on the apparent confusion of multiple ropes, chains, buckets, fenders and pieces of canvas. I suspect if you sailed these barges there was no confusion, and you knew exactly where everything was, and it was in the correct place.

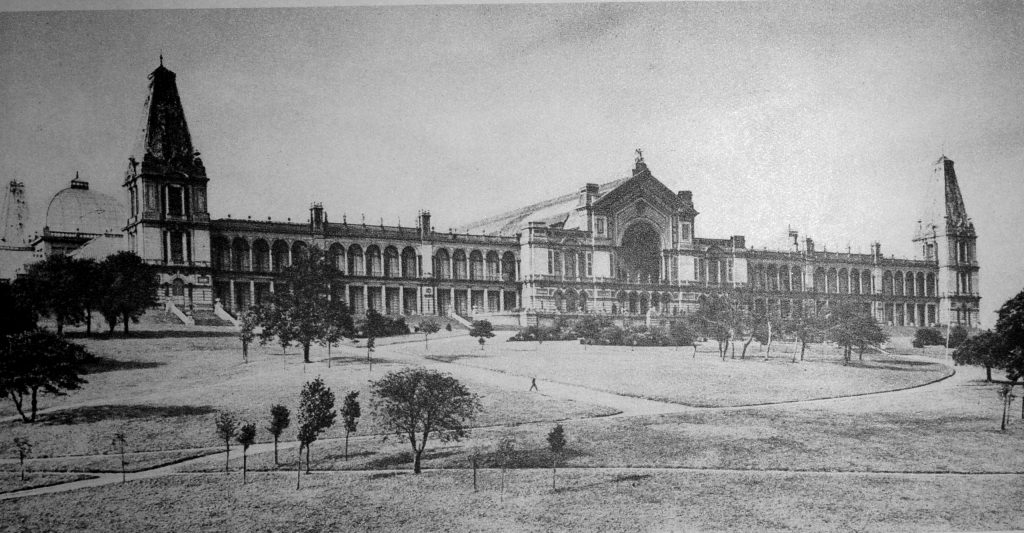

To finish this rather random survey of early 20th century London, a visit to north London and Alexandra Palace:

The Grand Hall which ran back from the taller part of the central façade:

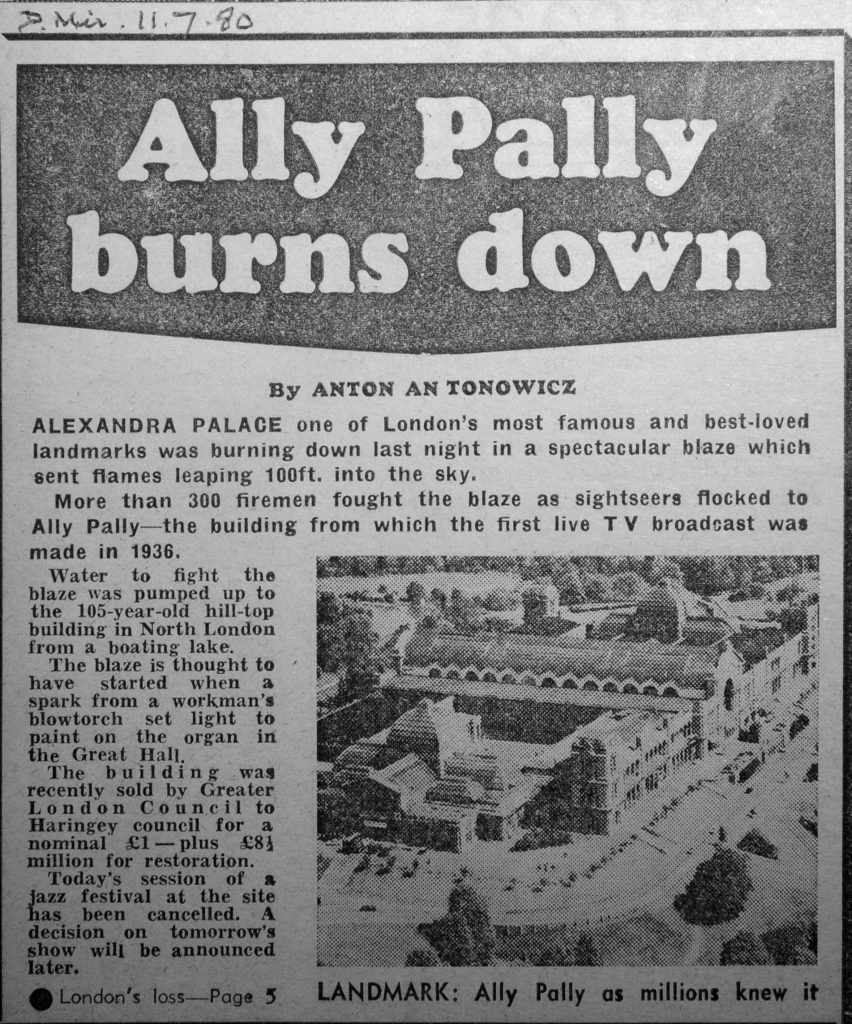

The Alexandra Palace photos are an example of why I love second hand books, as you never know what previous owners have left between the pages.

Alexandra Palace suffered a severe fire in 1980, and the previous owner of my copy of Wonderful London put a number of newspaper clippings next to the page with the original photos. These report on, and show the extent of the 1980 fire:

I love the understatement within the last paragraph, that whilst today’s jazz festival had been cancelled, a decision would be taken on the following day’s show.

The damage to the building was extensive:

The old Grand Hall was almost destroyed. Compare the following post fire photo with the photo of the hall from Wonderful London.

With the decline in newspaper readership as the Internet takes over, the habit of taking clippings from newspapers and putting them between the relavent pages of books will become a dying art.

A shame, as they provide an extra dimension to the life of a book. Whilst a book is a snapshot of the time it was published, additions by owners over time tell the story of the journey the book has taken to get to its current owner.

Wonderful London offers a brilliant snapshot of the city as it was in the early decades of the 20th century. Around 100 years later, many of the places featured, the way people lived and worked have changed considerably, however many of the views are much the same.

What the book does prove is how rich and diverse the city has always been, and how there is something of interest on almost any street corner, or in the case of Merton, even under the cabbages in an allotment.