London always surprises, I thought the search for this location would be simple, but I found a lost passageway and a 19th century plot to murder the government of the country.

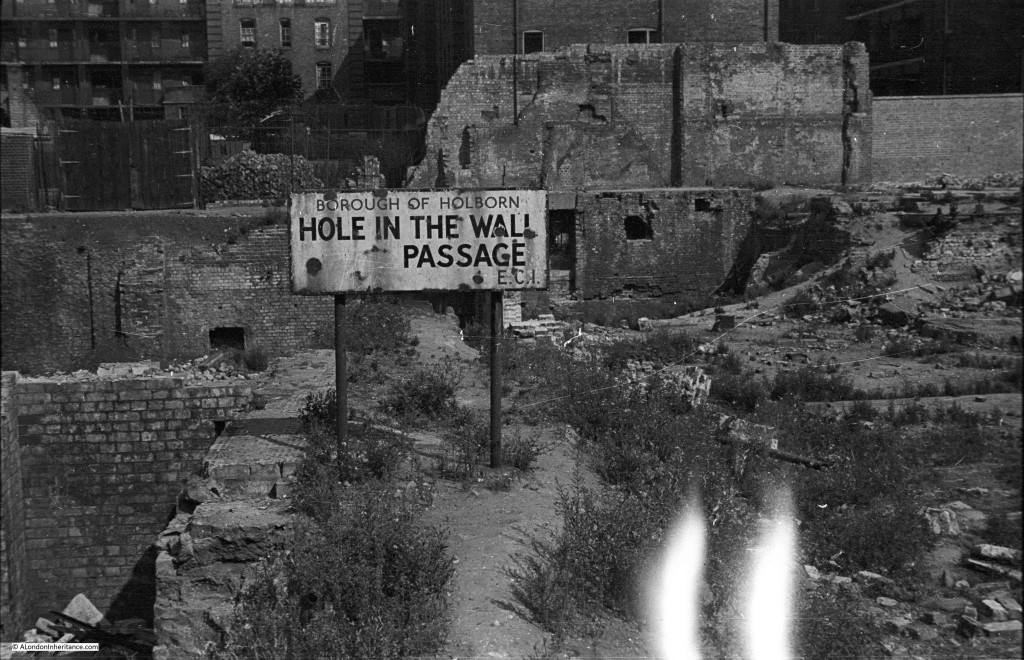

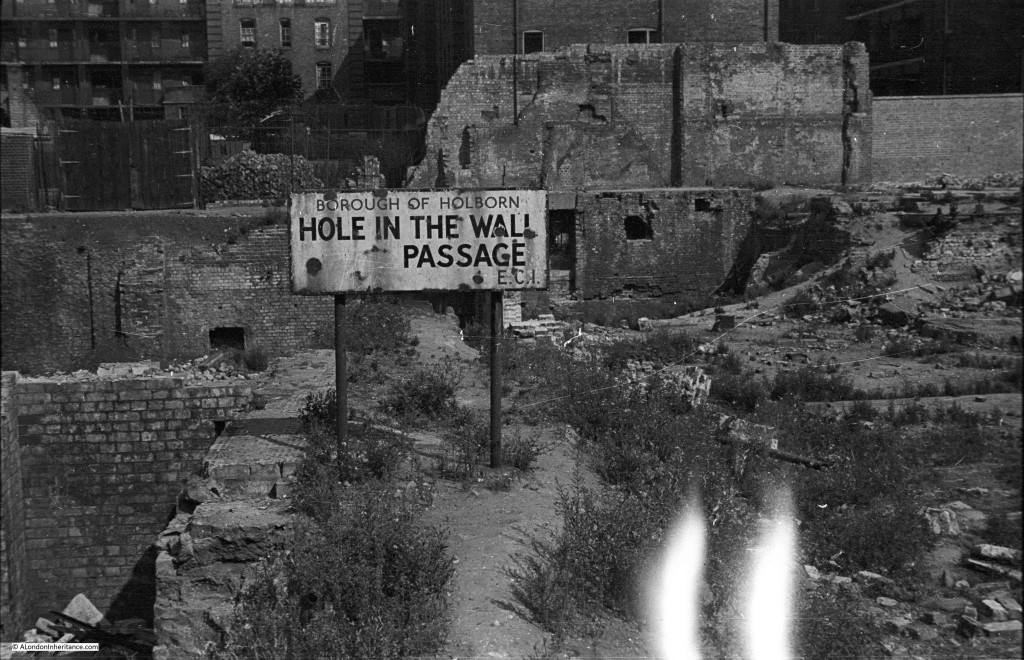

This is one of the photos my father took across London just after the last war showing one of the many locations devastated by bombing.

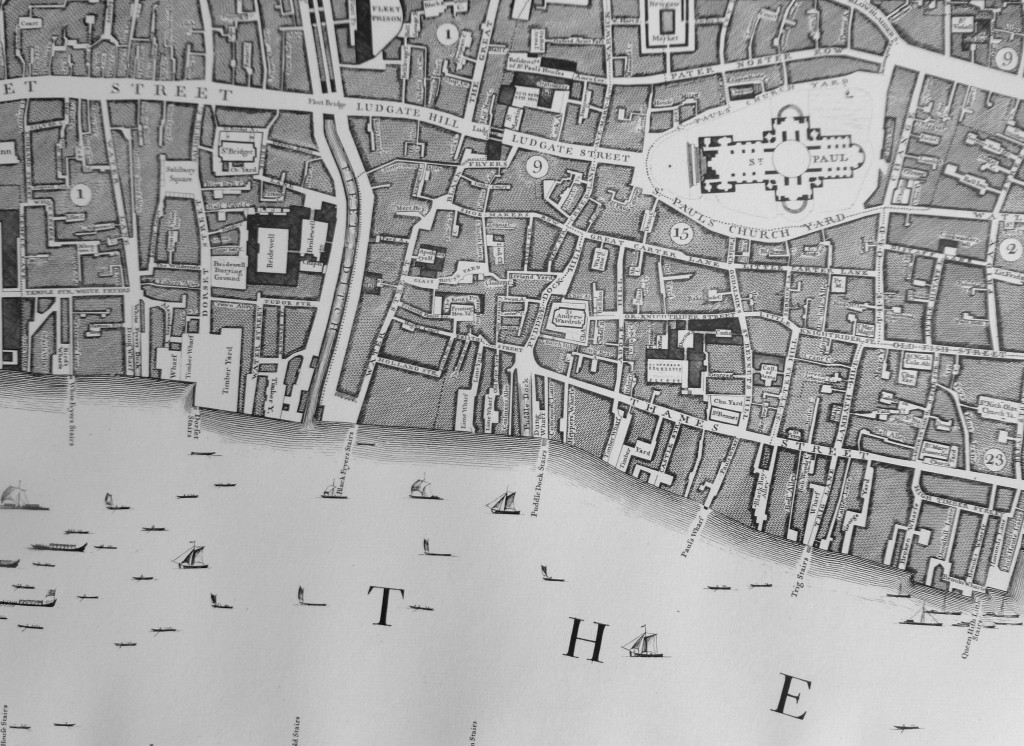

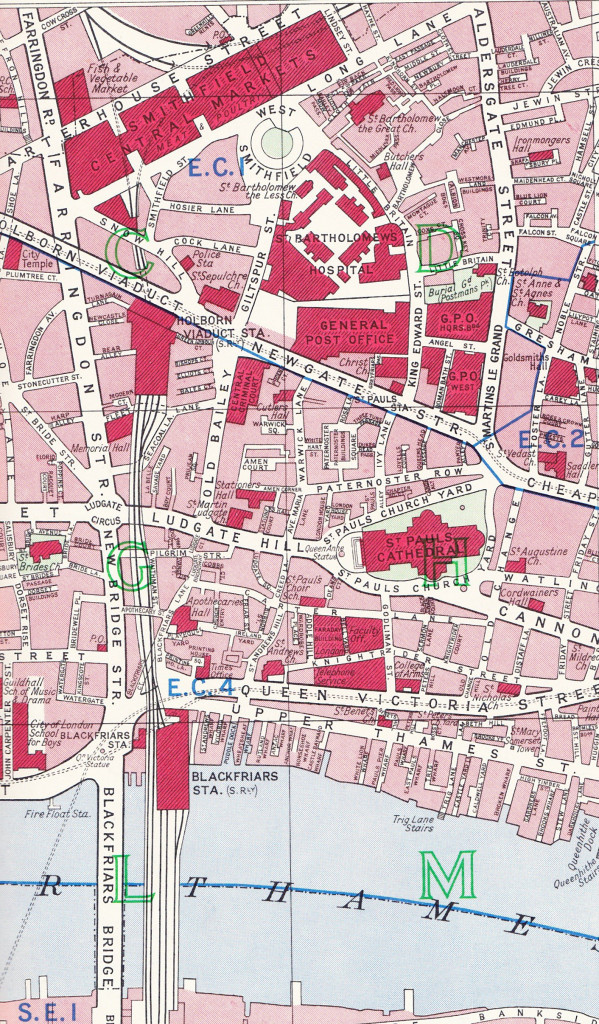

Finding this location should have been easy, the photo provides the name and the borough, however I could not find Hole In The Wall Passage on any of my maps from either before or after the last war.

Finding this location should have been easy, the photo provides the name and the borough, however I could not find Hole In The Wall Passage on any of my maps from either before or after the last war.

I found one of the few references to the location of Hole In The Wall Passage in “A Topographical Dictionary of London And Its Environs”, by James Elmes published in 1831:

“Hole in the Wall Passage or Alley, Leather Lane, is about 12 houses on the left hand in Baldwin’s Gardens going from Leather Lane.”

There was also a pub called the Hole In The Wall at 21 Baldwin Gardens during the 18th and 19th centuries. Was the pub named after the passage or the passage named after the pub?

The only reference I can find to Hole In The Wall Passage being shown on a map is from the National Archives where there is a document from the 26th February 1955 covering the following legislation:

Rights of Way: Stopping up of Highways (London) (No. 13) Order, 1955; Statutory Instrument 1955, No. 352; Location: Hole-in-the-Wall Passage, Baldwin’s Place and Verulam Street in the Metropolitan Borough of Holborn in the County of London

which covered the complete closure, or partial stopping up of a number of public spaces in the area. This confirms when Hole In The Wall Passage finally disappeared. Unfortunately, the National Archives record has not been digitised, so it will have to wait for a visit when hopefully I will finally see a map with Hope In The Wall Passage marked.

Despite the fact that Hole In The Wall Passage had almost certainly disappeared, I still wanted to see the location to check if there was any remaining indication that it had been there. I walked down Baldwin’s Gardens from Grays Inn Road only to find the road blocked and rebuilding taking place where Hole In The Wall Passage would have been located.

Hole In The Wall Passage would have been roughly where the middle of the new steel work is located.

Looking back at my father’s original photo, I believe the photo was taken on Hole in The Wall Passage looking towards Baldwin’s Gardens. The mounting of the sign looks temporary and it may have been placed across the passageway to mark the original location. The name sign looks as if it has suffered some damage and may have been the original wall mounted sign.

If you look back at the original photo, you can just see some flats in the background. These are still there. I took the following photo through the fencing surrounding a primary school playground from Baldwin’s Gardens:

I walked down to Dorrington Street which would have been the other end of Hole In The Wall Passage through Leigh Place. This is also a narrow alley and gives an indication of what Hole In The Wall Passage may have looked like:

One of the other references I found for Hole in the Wall Passage was in “London” by George H. Cunningham, published in 1927, which provided a rather sinister reference to the passageway:

“It was here in 1820 that the Cato Street conspiracy was formed to kill Wellington, Canning, Eldon and other Cabinet Ministers. The arms and powder were kept here.”

So what was the Cato Street conspiracy and what part did Hole In The Wall Passage play?

The later part of the 18th century and early part of the 19th century was a time of considerable change in the country. The industrial revolution was now well underway, the Napoleonic wars had finished, people were moving from the countryside to the towns, there was inflation and food shortages.

In the last decade of the 18th century there were riots and destruction of some of the new industrial infrastructure with the government’s response being the Combination Act of 1799 which outlawed the gathering of working men for common purpose. This was followed by the rise of the Luddite movement which started in 1811 and violently put down with show trials and harsh penalties in 1813.

One of the London radicals who protested against the conditions being imposed by government was Arthur Thislewood, and it was Thislewood who led the Cato Street conspirators, so named after their meeting place prior to their attempt to murder many members of the government.

Thislewood had intelligence that the Cabinet were meeting at Lord Harrowby’s home in Grosvenor Square. The plan was to burst into the meeting, murder the Cabinet members, behead them and then parade their heads on spikes through London.

Among the group of almost thirty conspirators there was a spy who passed on details of Thistlewood’s plan. A contingent of police later supported by soldiers stormed the conspirators meeting place in Cato Street, resulting in the arrest of the majority, including one named Tidd who lived in Hole In the Wall Passage.

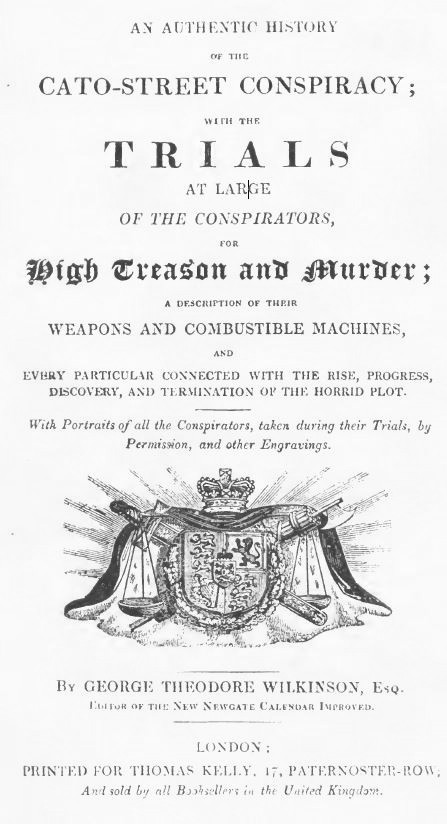

From “An Authentic History Of The Cato Street Conspiracy” by George Theodore Wilkinson published soon after the trial of the conspirators in 1820:

“The following account of Richard Tidd was given about the period of his arrest. He was about 50 years of age, and lived with his wife and family in a small and miserable dwelling in Hole-in-the-Wall Passage, leading from Baldwin’s Gardens to Dorrington Street. His family consisted of one daughter and two orphan children, whom he had taken under his care.

He had been esteemed among his neighbours, and those who had employed him in his trade, as an industrious sober man, and an excellent workman. He had earned by his own hands forty shillings a week, and very often a greater sum. During the whole course of his life, he was never known to neglect his work, or become inebriated; but with the last week he had been in a drunken state and his family had been at a lost to account for the extraordinary change in his conduct.

On Wednesday night, three men came to Tidd whilst in such a state of drunkenness as scarcely to be able to keep his legs, and forced him away, notwithstanding the earnest entreaties and remonstrances of his wife and family. Nothing was said by the men who took him away, as to their object either to the wife or any one in the house; and during the whole night, and the greater part of the next day, they were in total ignorance of the circumstances since disclosed, and were at a loss to account for the absence of Tidd. In the morning (Thursday), between seven and eight o’clock, two men came to the house, laden with a box of considerable size, and, putting It down on the floor said “they would call in a few minutes for it.” The men refused to answer the interrogatories put to them as to their object in leaving the box, and only repeated, that they would call in a short time, and take it away. Very soon afterwards, two more men came with a large bundle of sticks, some of them of the thickness of a man’s wrist. these were left in a similar manner, and the men also refused to answer any questions, saying only, that they would call again for them in a few minutes. ten minutes had not elapsed before two police-officers entered the house and seized the box and sticks. When opened , the box was discovered to contain a great number of pike-heads, sharpened ready for use. The sticks were also seized, and carried away by the officers. It would appear, from this statement that Tidd was taken by the three men whom we have described to the stable in Cato Street, where he was subsequently apprehended, and carried to Bow Street, together with several others.”

So that is the connection between the Hole In the Wall Passage and the Cato Street Conspiracy.

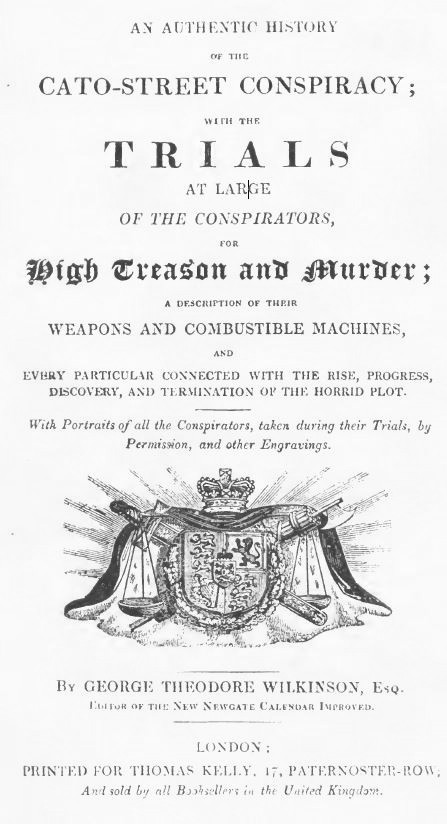

The book on the Cato Street Conspiracy is a wonderfully dramatic account of the event, the title page gives an indication of what is to come:

The opening paragraphs sets the scene:

“On the morning of Thursday the 24th of February 1820, the metropolis was thrown into the greatest consternation and alarm, by the intelligence, that, in the course of the preceding evening, a most atrocious plot to overturn the government of the country, had been discovered, but which, by the prompt measures directed by the privy council, who remained sitting the greatest part of night, had been happily destroyed by the arrest and dispersion of the conspirators. Before day-light the following proclamation was placarded in all the leading places in and about London ;-

LONDON GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY

Thursday, February 24, 1820

Whereas Artuhur Thistlewood stands charged with high treason, and also the wilful murder of Richard Smithers, a reward of One Thousand Pounds is hereby offered to any person or persons who shall discover or apprehend, the said Arthur Thistlewood, to be paid by the lords commissioners of his majesty’s treasury; upon his being apprehended and lodged in any of his Majesty’s gaols. And all persons are hereby cautioned upon their allegiance not to receive or harbour the said Arthur Thistlewood, as any person offending herein will be thereby guilty of high treason. “

Later in the book there is an account of the storming of the assembly place of the conspirators in Cato Street:

“The officers, with a resolution and courage which does them honour, considering the desperation and determination of these characters immediately ascended the ladder without securing the persons below. They merely gave directions to those who followed, to keep them secure, and they thought that would be enough, without actually confining them. The first man who went up was a person of the name of Ruthven, he was followed by a man named Ellis: after who came a man named Smithers, who met his death by the hand of Thistlewood.

On Smithers ascending the ladder, either Ings or Davidson hallooed out from below, as a signal for them to be on their guard above, and upon Ruthven ascending the ladder, Thistlewood, who was at a little distance from the landing place, and who was distinctly seen, for there were several lights in the place, receded a few paces, and the police-officers announced who they were, and demanded a surrender. Smithers unfortunately pressed forward in the direction in which Thistlewood had retreated, into one of the small rooms over the coach-house, when Thistlewood drew back his arm, in which there was a sword, and made a thrust at the unfortunate man, Smithers, who received a wound near his heart, and, with only time to exclaim, “Oh God !” he fell a lifeless corpse into the arms of Ellis. Ellis seeing this blow given by Thistlewood, immediately discharged a pistol at him, which missed its aim. Great confusion followed, the lights were struck out; the officers were forced down the ladder, which was so precipitous, being almost perpendicular, that they fell, and many of the party followed them.

Thistlewood, among the rest, came down the ladder; and not satisfied with the blood of one person, he shot at another of the officers as he came down the ladder, and pressed through the stable, cutting at all who attempted to oppose him, and made his escape out into John Street, the military not having yet arrived; and he was seen no more at that time, except with a sword in his hand in the Edgware Road. By the other persons an equally desperate resistance was made.

Conscious of the evil purpose for which they had assembled, they waited not to know on what charge they were about to be apprehended; but instantly made a most desperate resistance. Ings, Davidson and Wilson were particularly desperate, each, I believe, firing at some of the officers or military, who had only come to the ground on hearing the report of the fire-arms and not having been previously directed to the exact spot.

Not withstanding the resistance, however, which they so desperately made, and in which resistance Thistlewood, Tidd, Davidson, Ings and Wilson took a most active part, by attacking the officers and solders, the whole of the conspirators were, at length, fortunately overcome, and eventually eleven of them secured. Not on that night, however, for three out of the eleven for the time escaped, namely Thistlewood, Brunt, and Harrison. The officers, however not only secured on that night the eight men, but various articles of fire-arms, numerous weapons, and certain combustibles.”

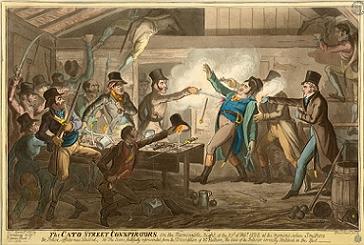

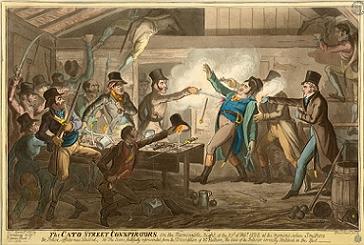

The point where the officers storm the meeting place of the conspirators in Cato Street is captured in the following drawing:

The building where the conspirators met and these events took place in Cato Street is still there, now with a blue plaque recording the event:

Cato Street is still a narrow street with entrances at each end through buildings. The entrance to Cato Street from Crawford Place.

Cato Street is still a narrow street with entrances at each end through buildings. The entrance to Cato Street from Crawford Place.

The penalty for each of the conspirators was very severe, probably to be expected given their intentions, however I was very surprised that this form of execution was still available in 1820. Again, from the account:

“That you, and each of you, be taken from hence to the gaol from whence you came, and from thence that you will be drawn upon a hurdle to a place of execution, and be there hanged by the neck until you be dead; and that afterwards your heads shall be severed from your bodies, and your bodies shall be divided into four quarters, to be disposed of as his majesty sees fit. And may God of his infinite goodness have mercy on your souls !

The prisoners were then removed from the bar; some of them, particularly Thistlewood, Brunt and Davidson, appearing to be wholly unconcerned at the awful sentence which had been passed upon them, and the whole of them evincing great firmness and resignation.

Tidd complained of the immense weight of his irons.”

The executions was carried out shortly after the trial although some of the sentences were changed.

Only Thistlewood, Brunt, Davidson and Tidd were to be executed, the rest of the conspirators had their death sentence commuted to transportation for life.

The death sentence was also changed so that the part which directed that their bodies be quartered was now removed. The book of the conspiracy provides a detailed account of the executions. Given that my search for the Cato Street Conspiracy started with Tidd, who “lived with his wife and family in a small and miserable dwelling in Hole-in-the-Wall Passage” we can follow his last hour:

“Tidd, who had stood in silence, was now summoned to the scaffold. He shook hands with all but Davidson, who had separated himself from the rest.

Ings again seized Tidd’s hand at the moment he was going out, and exclaimed, with a burst of laughter “Give us your hand, Good-bye !”

A tear stood in Tidd’s eye, and his lips involuntarily muttered, “My wife and –!” Ings proceeded – “Come my old cock-o-wax, keep up your spirits it will be over soon.

Tidd immediately squeezed his hand, and ran towards the stars leading to the scaffold. In his hurry, his foot caught the bottom step, and he stumbled. He recovered himself, however, in an instant, and rushed upon the scaffold, where he was immediately received with three cheers from the crowd, in which he made a slight effort to join.

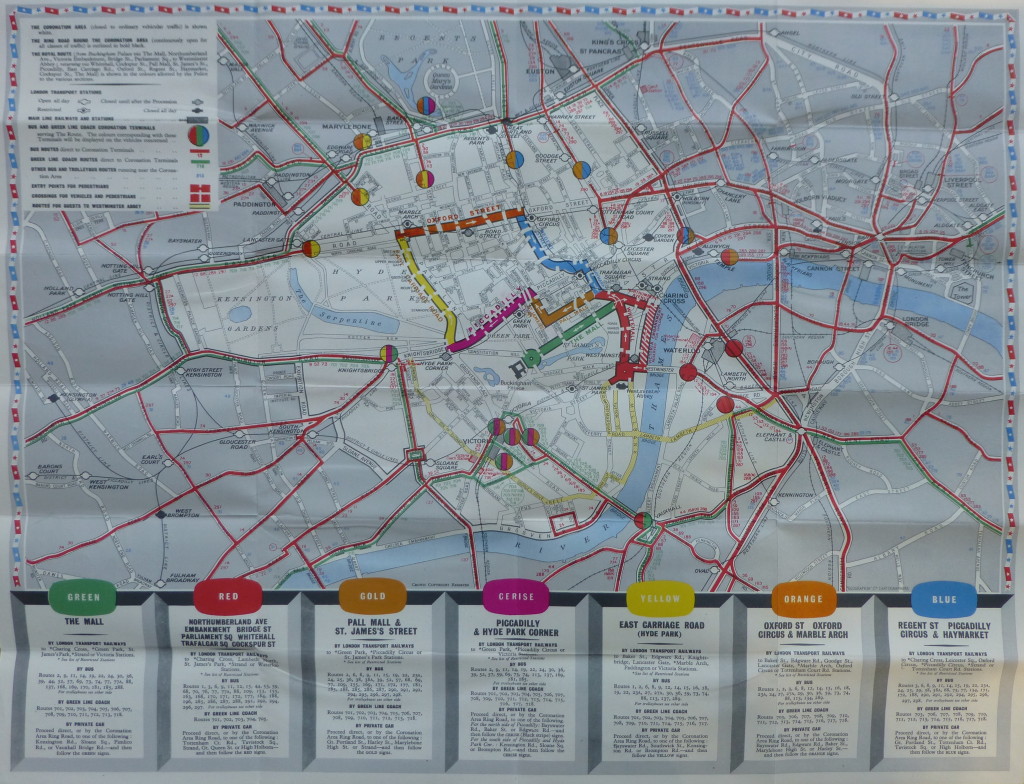

The applause was evidently occasioned by the bold and fearless manner in which the wretched man advanced to his station. He turned to the crowd who were upon Snow Hill, and bowed to them. He then looked down upon the coffins and smiled, and turning round to the people who were collected in the Old Bailey towards Ludgate Hill bowed to them. Several voices were again heard, and some in the crowed expressed their admiration of Tidd’s conduct.

The rope having been put round his neck, he told the executioner that the knot would be better on the right than the left side, and that the pain of dying might be diminished by the change. he then assisted the executioner, and turned round his head several times for the purpose of fitting the rope to his neck. He afterwards familiarly nodded to some one whom he recognised at a window, with an air of cheerfulness. He also desired that the cap might not be put over his eyes, but said nothing more. He likewise had an orange in his hand, which he continued to suck most heartily. He soon became perfectly calm, and remained so till the last moment of his life.”

Mr Richard Tidd of Hole In The Wall Passage. Drawn at the time of his trial:

I wonder what happened to the family that Tidd left behind? How did they survive and did they still continue living in Hole In The Wall Passage?

I really did not expect to find such a story when I first started researching the location of my father’s original photo. Hole In The Wall Passage has left no trace, but fortunately we can still follow the story of one of the inhabitants.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- London by George Cunningham published in 1927

- A Topographical Dictionary Of London And Its Environs by James Elmes published in 1831

- An Authentic History Of The Cato Street Conspiracy by George Theodore Wilkinson

alondoninheritance.com