The Evening News published two London Year Books, one for 1953 and the other for 1954. I cannot find year books for any other years, so I assume it was for just these two.

I wrote about the 1953 edition in this post, and for today’s post, on the eve of 2024, a review of the 1954 edition, taking a look at what London was like 70 years ago, key events of the previous year, and expectations for the coming year.

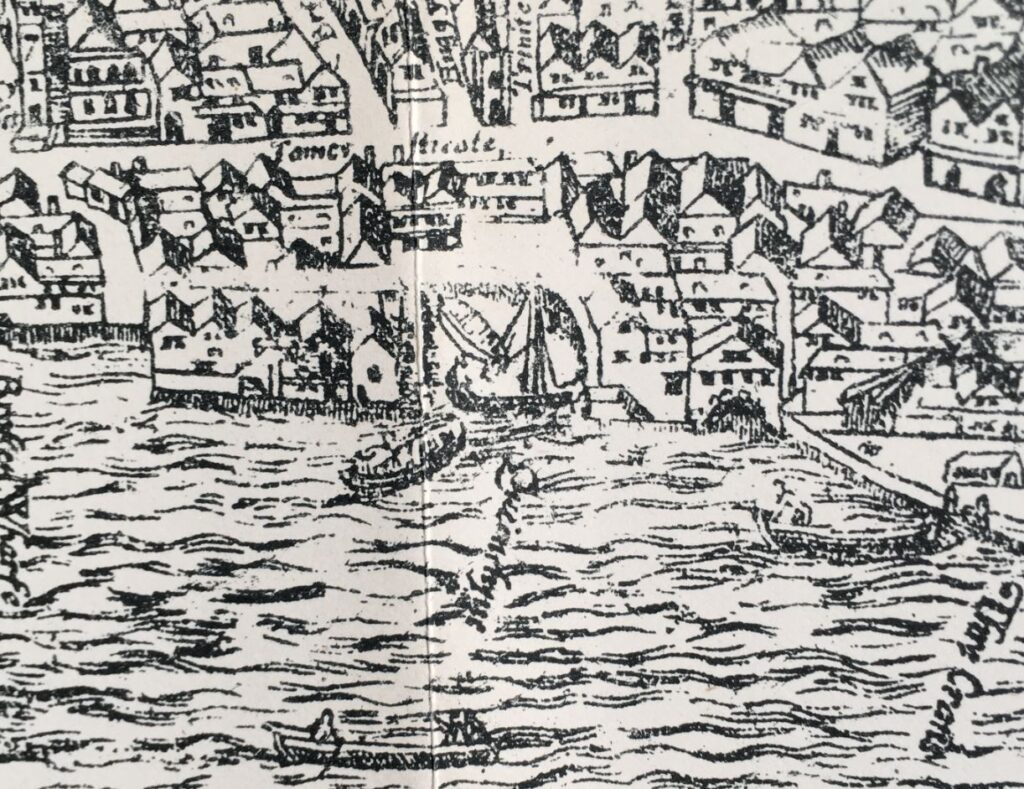

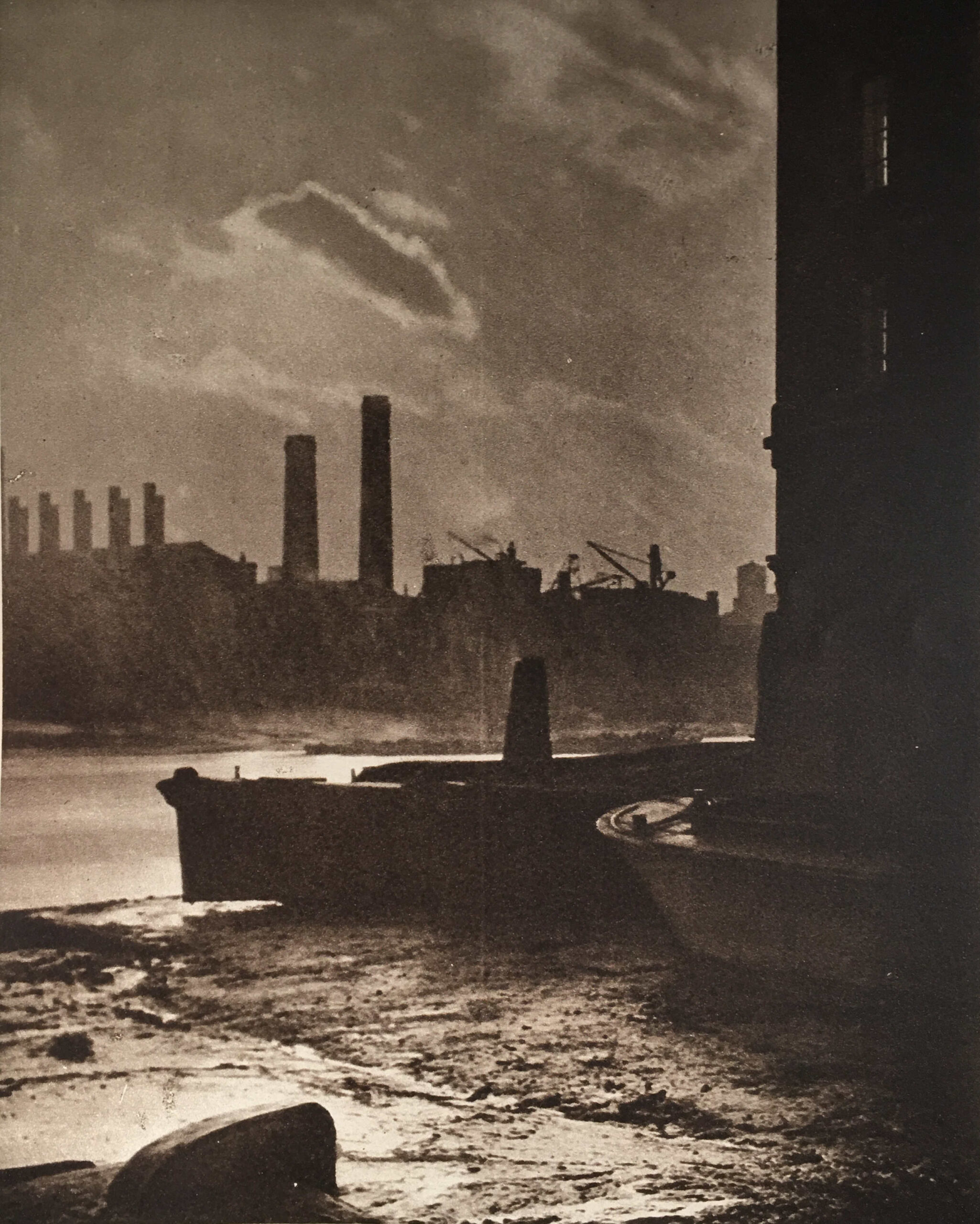

In very many ways, London has changed significantly in the past 70 years, but much else remains the same. In 1954, the city was still recovering from the ravages of the Second World War, a process that would take the following two decades. The Docks were still a major source of trade and employment with the Thames still a busy transport route.

The City of London was a major financial centre, and in 1954 there was no indication at all that the Isle of Dogs would become a rival financial centre (although in 2023, some companies are planning to move back to the City).

The population of London was very slowly recovering from the low levels seen as a result of migrations out during and immediately after the war.

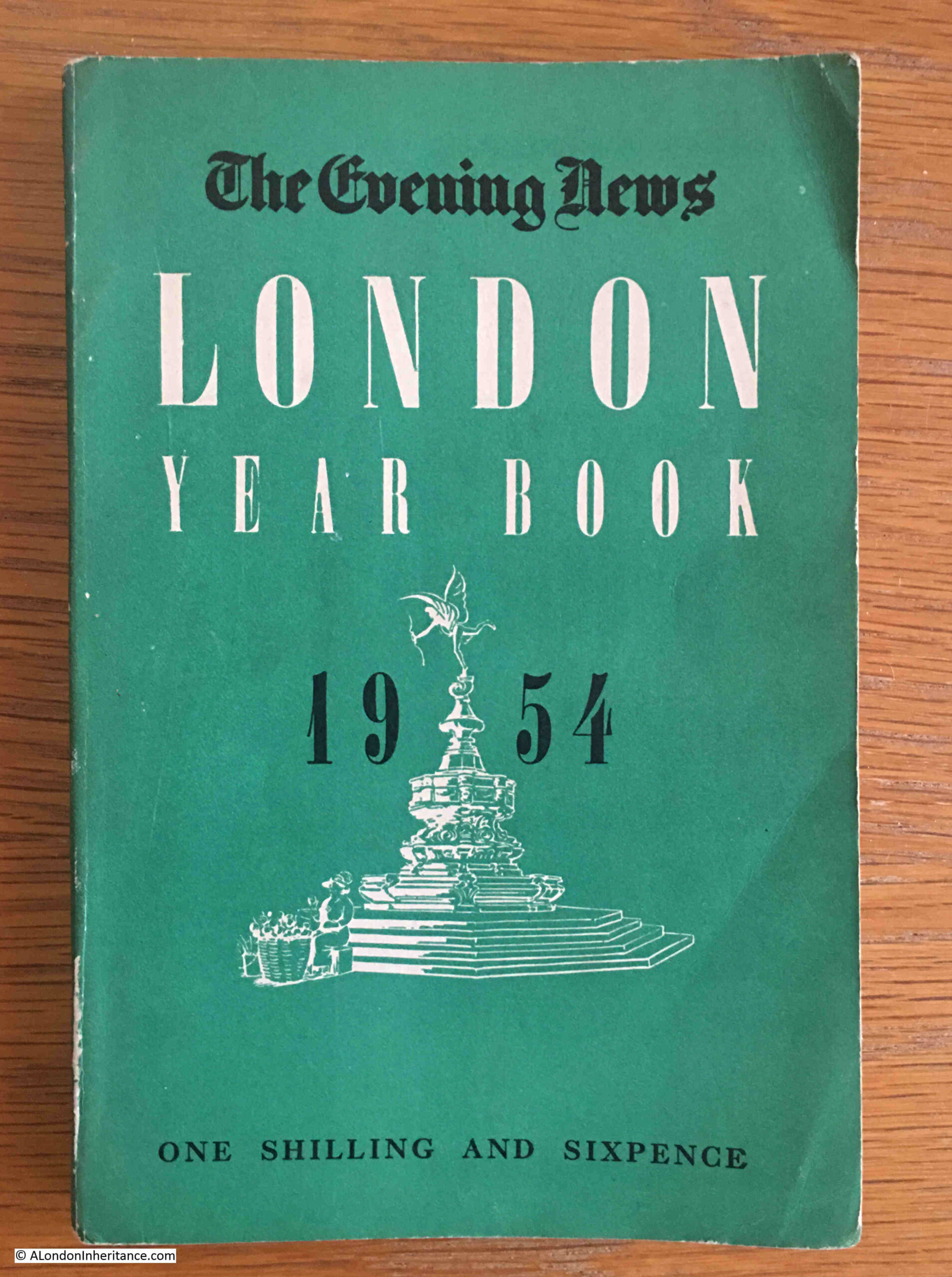

The cover of the Evening News Year Book for 1954:

The year book is a densely packed little book about the city, claiming to have 10,000 facts about London within its 192 pages.

The 1954 edition starts with a review of 1953, with the heading “A Glorious London Year”, with, as in 2023, the main event of the year being a Coronation, which the book introduces with:

“‘What fun they had in 1953’. So, I feel, will your grandchildren exclaim when they turn over the pictures you have pasted in the big book, or listen to play-backs of newsreels and the famous films. But we know that it was more than fun. it was a flame that warmed and lit the island in that wet spring and summer.”

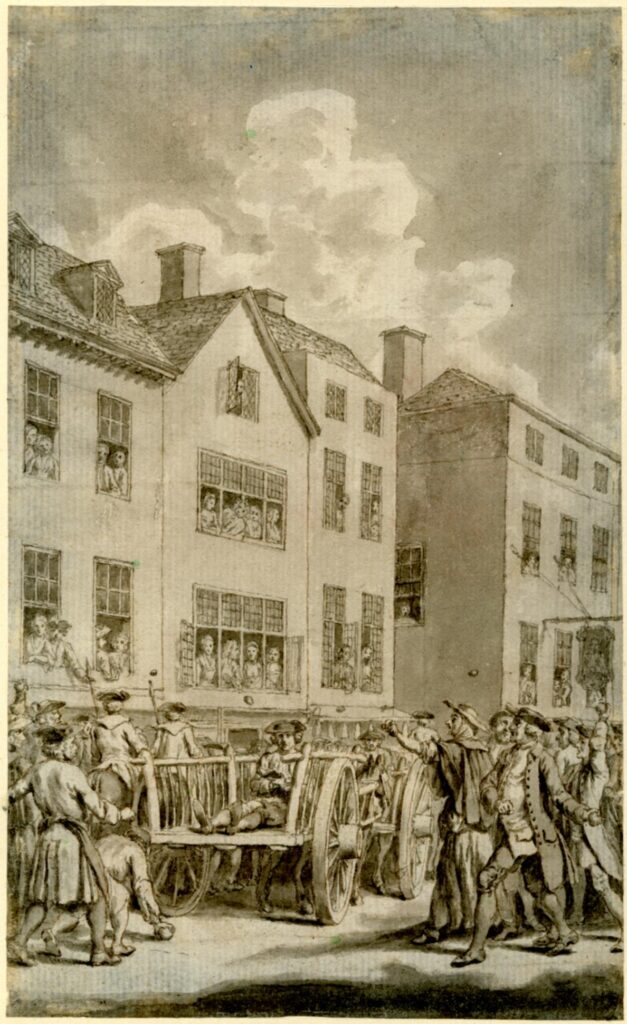

Although the Coronation was a highlight, there had been a number of tragic events in the previous couple of years, including in 1952, a major train accident at Harrow and Wealdstone Station:

This happened on the 8th of October, when “the Perth to Euston express smashed into a local train standing at Harrow and Wealdstone Station. Seconds later, the Euston to Liverpool Express ploughed into the wreckage. Altogether 111 people died.”

The accident apparently remains the worst peacetime accident on the British rail network. The following British Movietone newsreel provides a view of just how bad the crash was:

The other significant tragedy of 1953 was the flooding of January 1953, when “On the night of 31st January, nature dealt a savage blow along the East Coast – and London, too suffered. Here are the occupants of houses in Mary Street, West Ham, salvaging their property after flooding”.

The following newsreel provides an overview of the level of devastation caused by the floods across England, the Netherlands and Belgium:

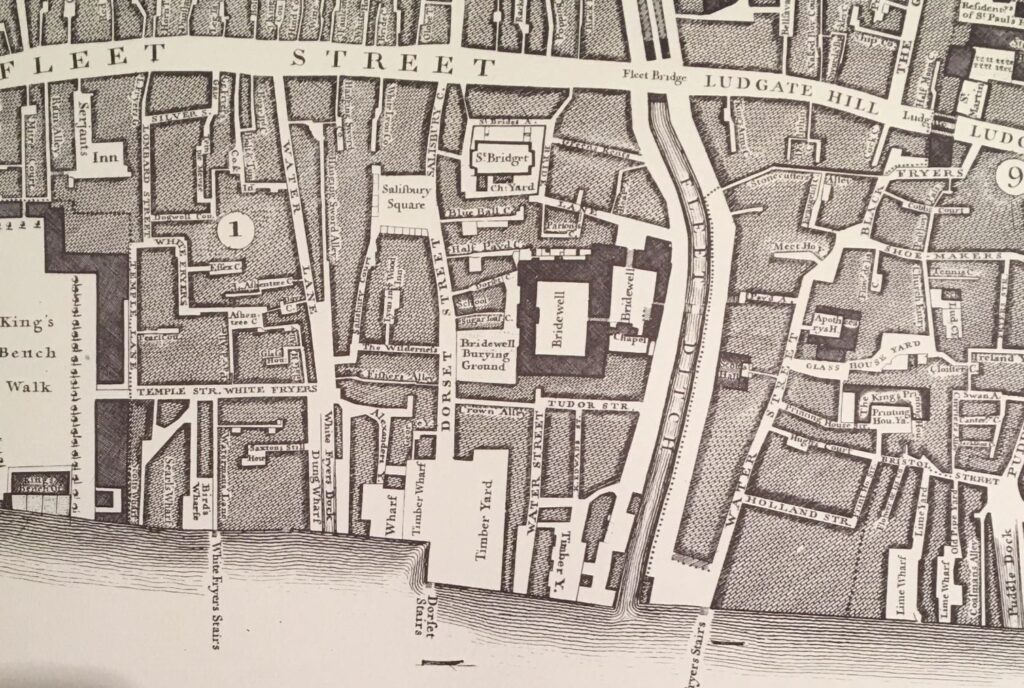

The Year Book included a section on “Excavating Ancient London”. The 1950s were a time of significant archaeological discoveries across London, with so many areas opened up for excavation following wartime bombing.

Many of these digs were led by Professor W.F. Grimes, who was Director of the Museum of London, and it was Grimes who wrote the pages in the Year Book on excavating London, starting with:

“Almost every year adds to the quota of new discoveries to the store of raw materials upon which the early history of London must be built. Many of these are chance finds, due to accidents of one sort or another; but interesting as they may be, they do not tell the expert anything like as much as finds which have been the outcome of carefully-controlled scientific excavations.”

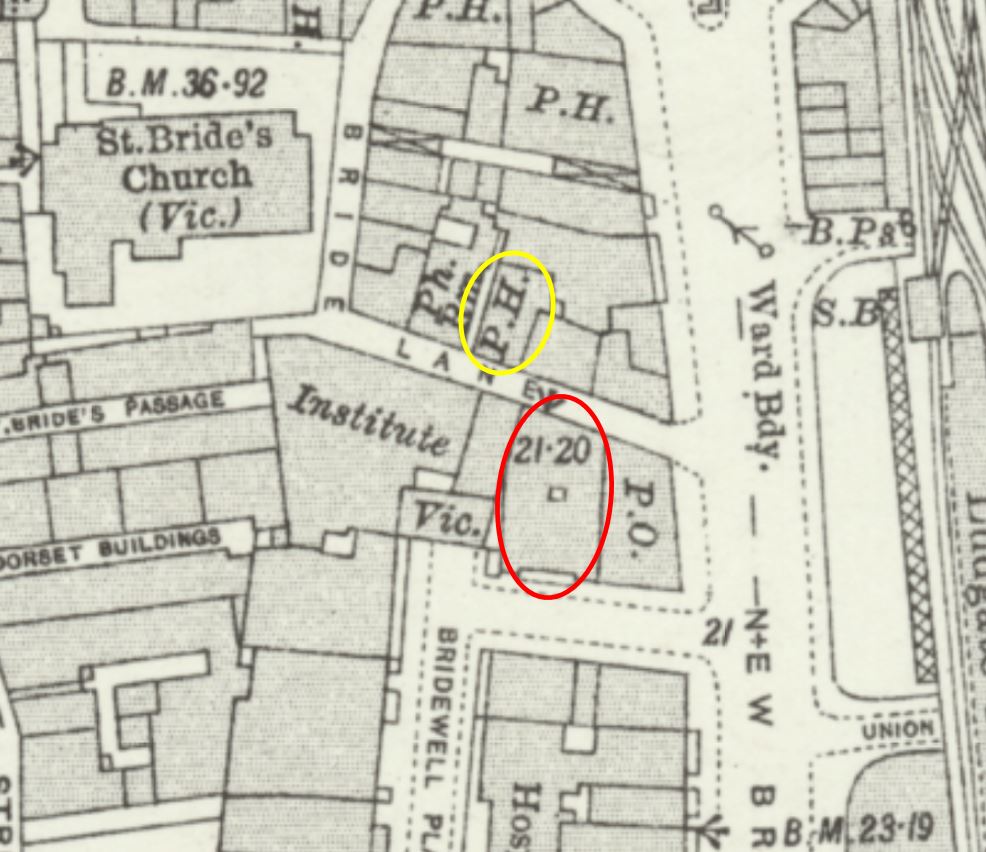

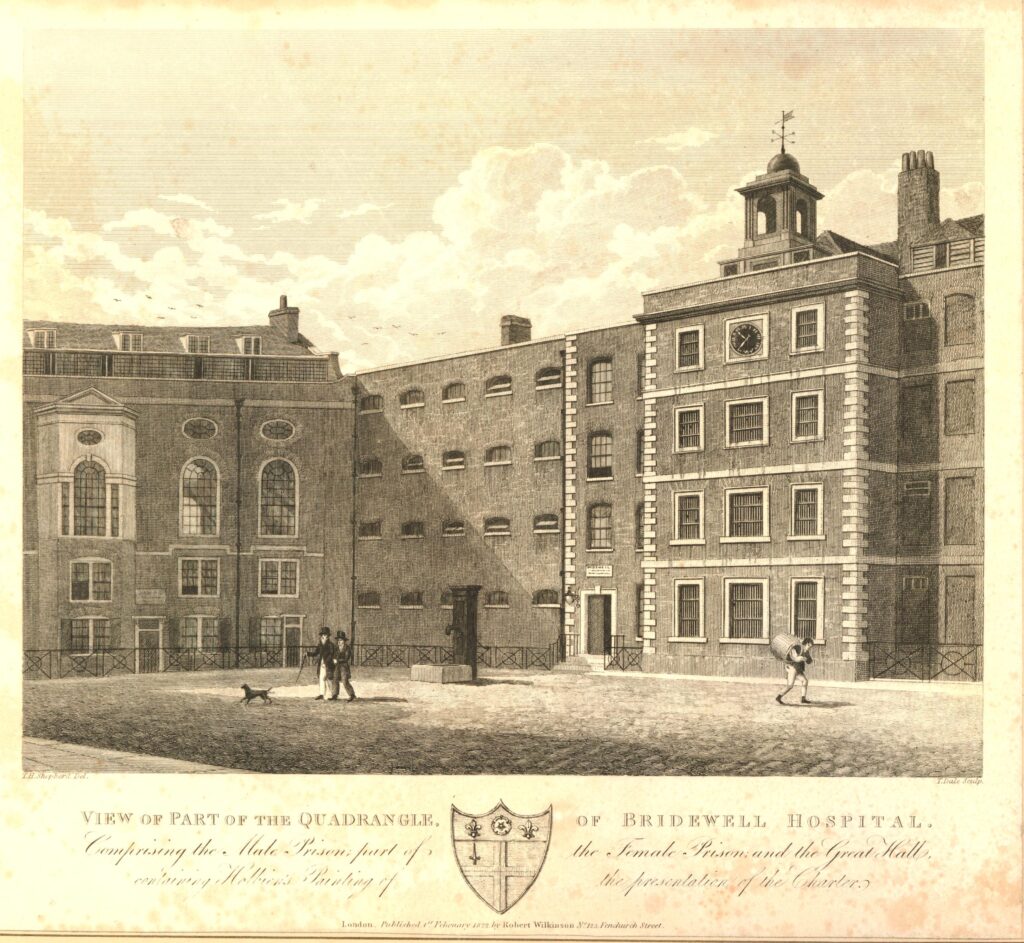

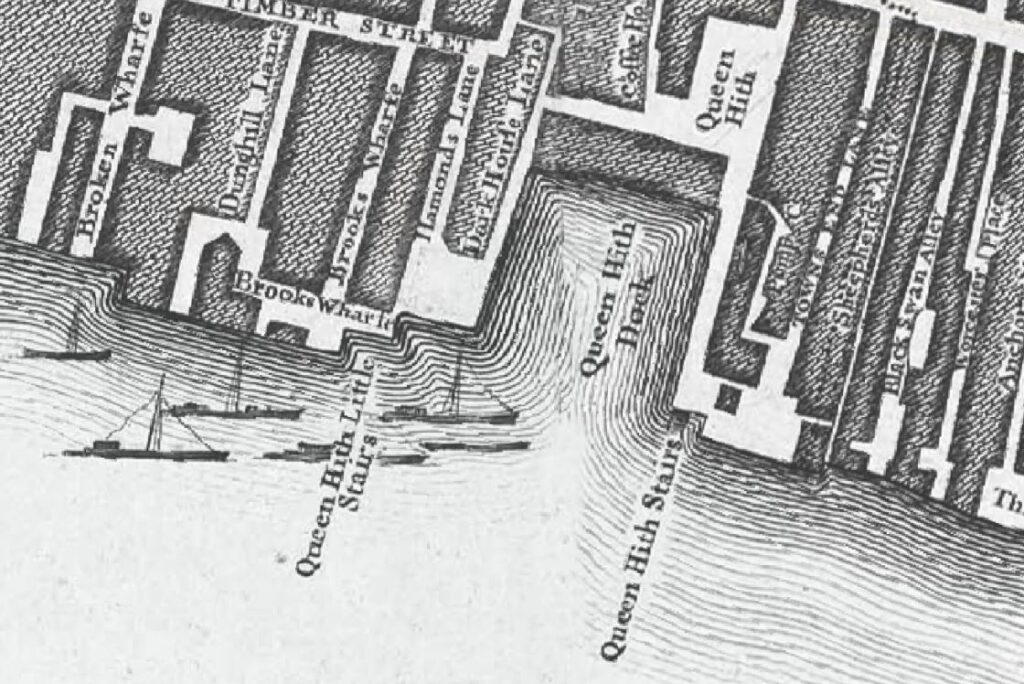

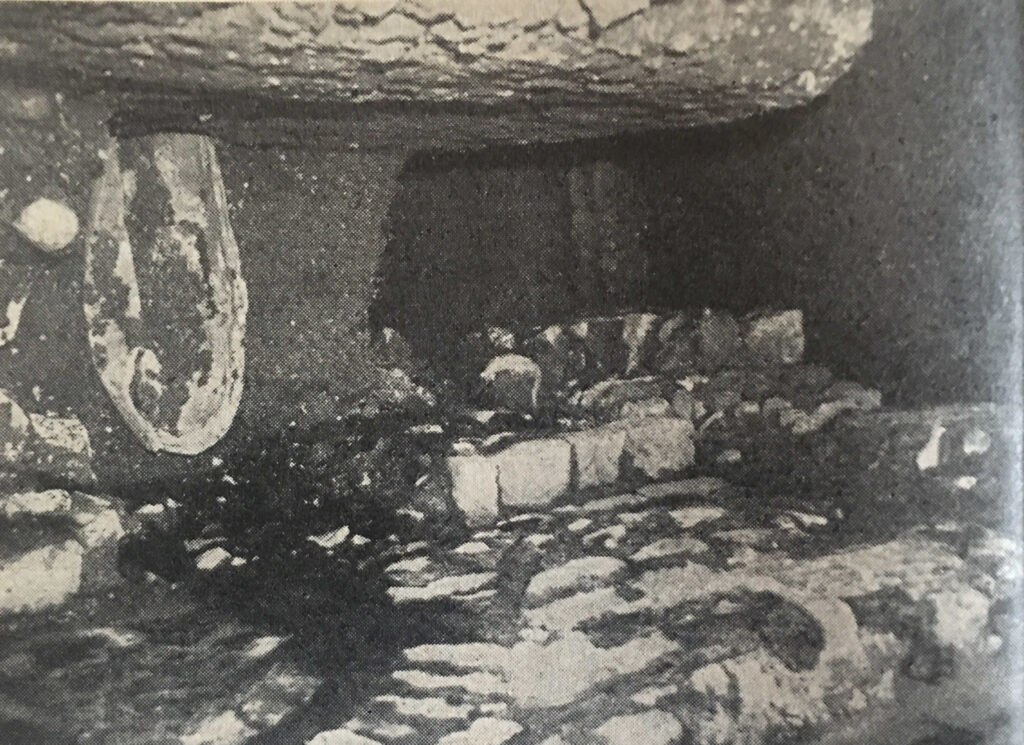

Grimes features two significant sites excavated during 1953. The first was the discovery of Roman mosaic floors in what would have been large houses along the banks of the Walbrook river. The second was at St. Bride’s, Fleet Street, where “discoveries have shed light upon the Roman period, the Anglo-Saxon period and the Middle Ages”.

The following photo shows “the excavations at St. Bride’s, Fleet Street, there can be seen in the distance, at right angles to the outside of the east wall, the first trace of the foundation of a Roman building. During excavations inside the church isolated pieces of tessellated pavement were found from time to time”:

And “the Roman stone foundation which was discovered running underneath the east end of St. Bride’s church”:

Grimes finished his section in the Year Book with “It is gratifying to record the enlightened intention of the Vicar and Churchwardens to undertake the expensive task of preserving these features in their rebuilt church for the benefit of future generations of Londoner’s”.

They truly did do a magnificent job with both preserving and displaying these historic features, as I discovered in this post on the church of St. Bride’s.

Another section in the 1954 Year Book looked at the Airports of London.

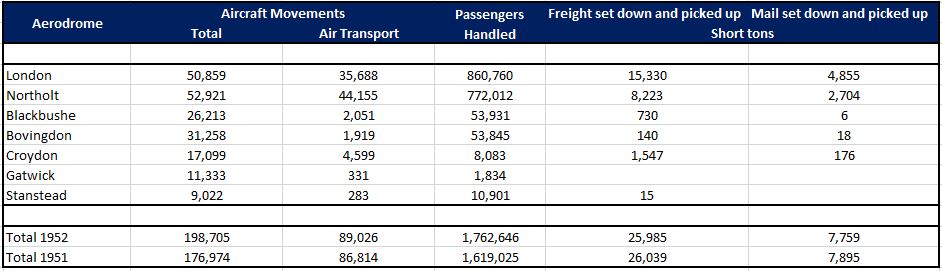

In the early 1950s, air traffic was gradually increasing, and London was served by seven airports, and the following table shows the 1952 traffic volumes at these airports (at the time, Heathrow had not taken on the name by which it is currently known, and was then called simply London Airport):

Remarkable when you compare the passengers handled figures that Gatwick and Stansted are now the second and third major airports serving London.

The London Airport / Heathrow was starting to become the major airport that it is today. The Year Book recorded that in the past three years, traffic at the London Airport had more than doubled.

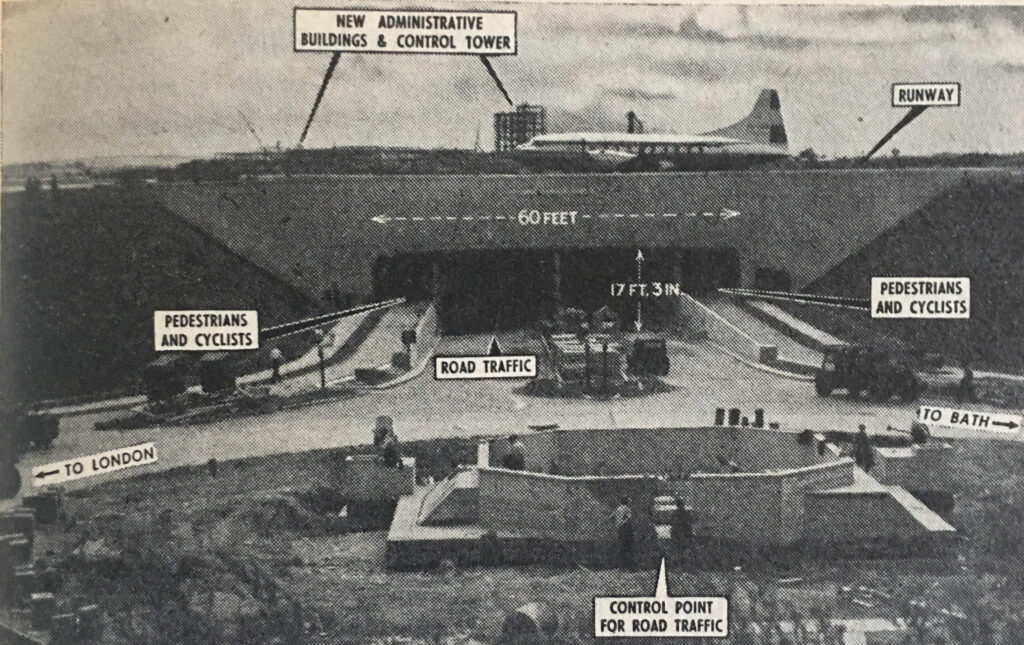

The infrastructure of the airport was also developing with the new access tunnel having been recently completed:

The Year Book reported that the access tunnel was part of a development scheme which was due for completion in 1960 and would cost around £6,700,000 and that by completion of this work, the airport would handle 3,250,000 passengers a year.

That expectation of 3.25 million compares to a pre-pandemic high figure of 80.9 million passengers in 2019.

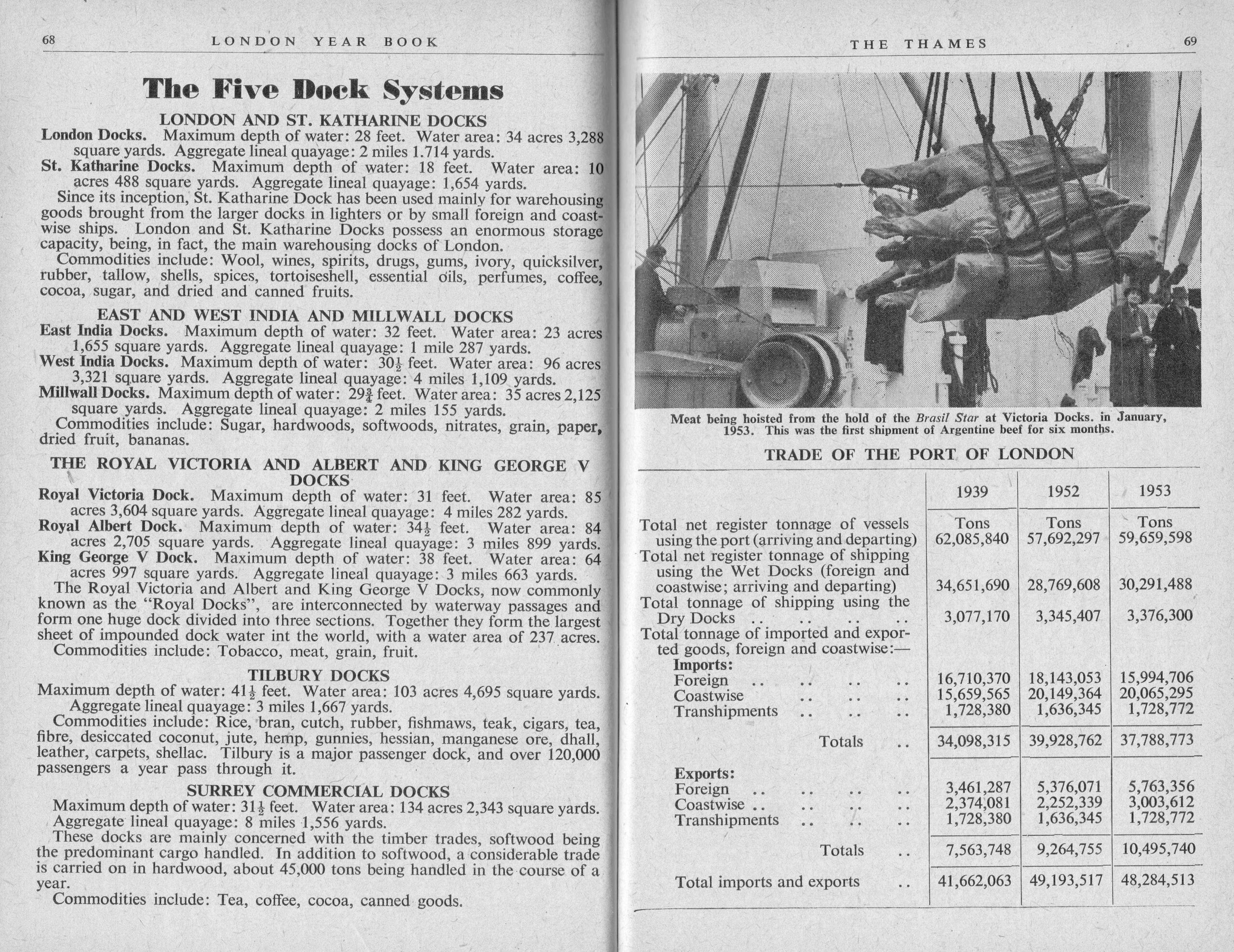

Whilst the London Airport was developing as a place of international trade and transport, the River Thames was still London’s major route for trade, and the Year Book recorded that the following docks were busy, and administered by the Port of London Authority:

London Docks, St. Katherine Docks, East India Dock, West India Docks, South-West India Dock, Millwall Docks, Royal Victoria Dock, Royal Albert Dock, king George V. Dock, Tilbury Docks, Surrey Commercial Docks.

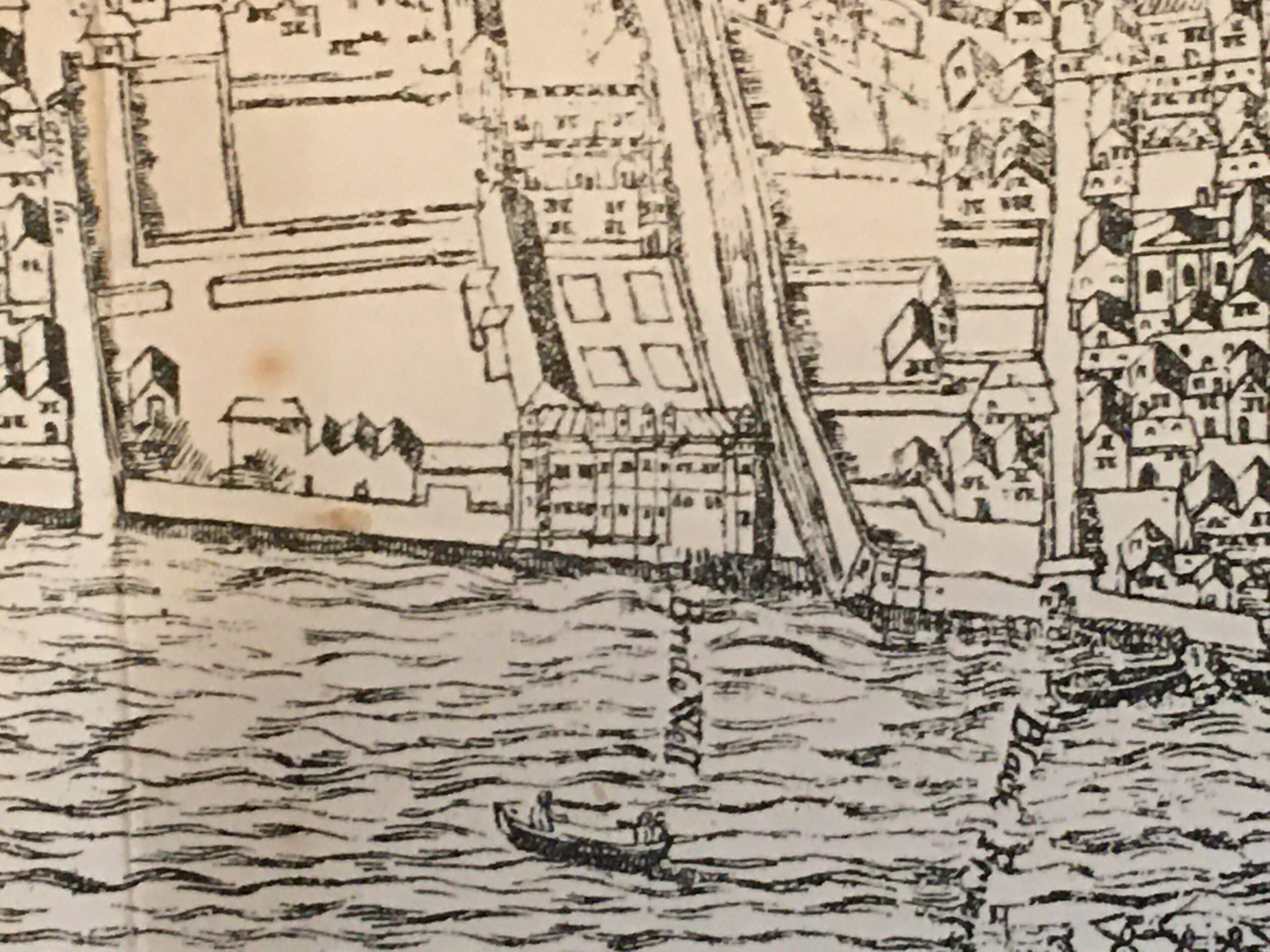

The Year Book introduced the Port of London, by: “The Port of London comprises 69 miles of the River Thames from the estuary to the landward limit of its tidal waters at Teddington, and five great dock systems which are situated within 26 miles of the tideway between Tilbury, some 24 miles inland from the sea, and Tower Bridge”.

In the early 1950s, the total volume of trade through the London dock system was still higher than pre-war figures, as illustrated by the following figures:

- 1939: Total Tons – 41,662,063

- 1952: Total Tons – 49,193,517

- 1953: Total Tons – 48,284,513

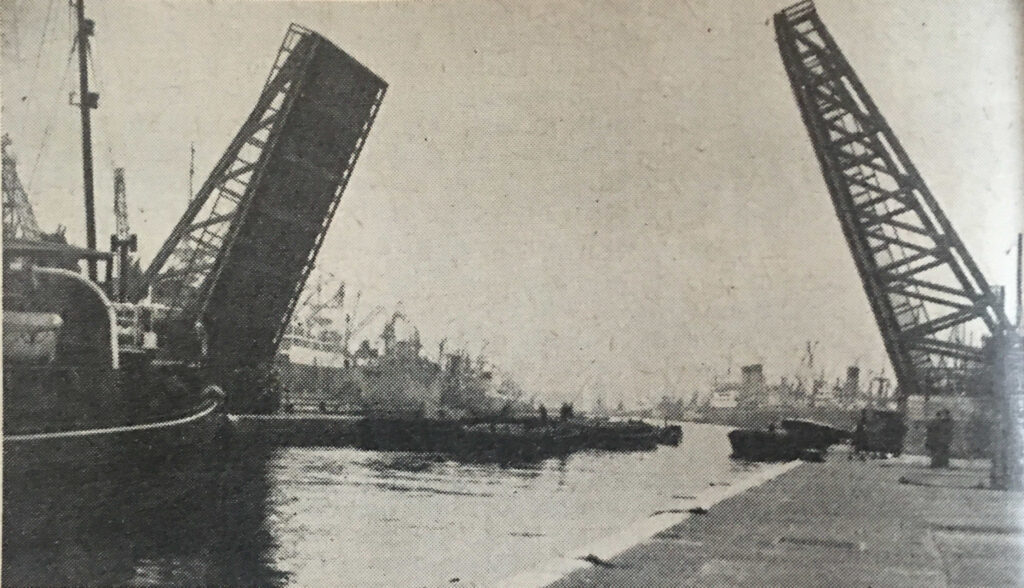

The size and complexity of the London dock system was remarkable. The following photo shows the bascule bridge at the King George V Dock which opens to allow a ship to enter the dock. The view is taken from the entrance lock, showing the dock in the background:

In 1954, the Inland Waterways were still an important part of the transport of goods to and from London, and then to the wider world. A section on the inland waterways shows just how interconnected the system was:

“The Inland Waterways controlled by the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive within the Greater London Area are the former Grand Union Canal and the Lee and Stort Navigation.

These waterways commence amidst London’s dockland and are, therefore, conveniently situated in relation to the Port’s world shipping activities. The principal routes are; London to the Midlands (Grand Union Canal); London to Hertford and Bishop’s Stortford (Rivers Lee and Stort). The route from London to the Midlands has two important junctions with the River Thames, one at Regent’s Canal Dock and the other at Brentford.

Regent’s Canal Dock, situated on the north side of the river at Limehouse, and approached by a sea lock 60ft wide, can accommodate ships of 300ft length. It has a waterway area of about 11 acres and is well equipped for dealing with coal and general merchandise.

From Regent’s Canal Dock goods are shipped by through-water route from London to the interior of Belgium, Holland, France, Switzerland, Canada, America, Scandinavia and the Mediterranean, thus linking England’s waterways with the other great canal systems of the world.”

Although the inland waterways network had been competing with the railways for the best part of a century, in the 1950s it was still carrying a significant amount of trade, with 3,068,000 tones carried in 1952 across the network of the Regent’s Canal, River Lee and the Grand Union Canal.

I doubt whether those working across this network and in the London docks could have foreseen the coming widespread use of the Container as a means of shipping goods, along with the rapid increase in the size of ships that would soon render the London Docks redundant

In the following 30 years after the 1954 Year Book, all the docks, with the exception of Tilbury, would close, resulting in a fundamental change in the relationship between London and the Thames.

The Year Book includes no indication that this would be the future of the docks, rather it gives impressive descriptions of the dock systems and the volume of trade through the Port of London:

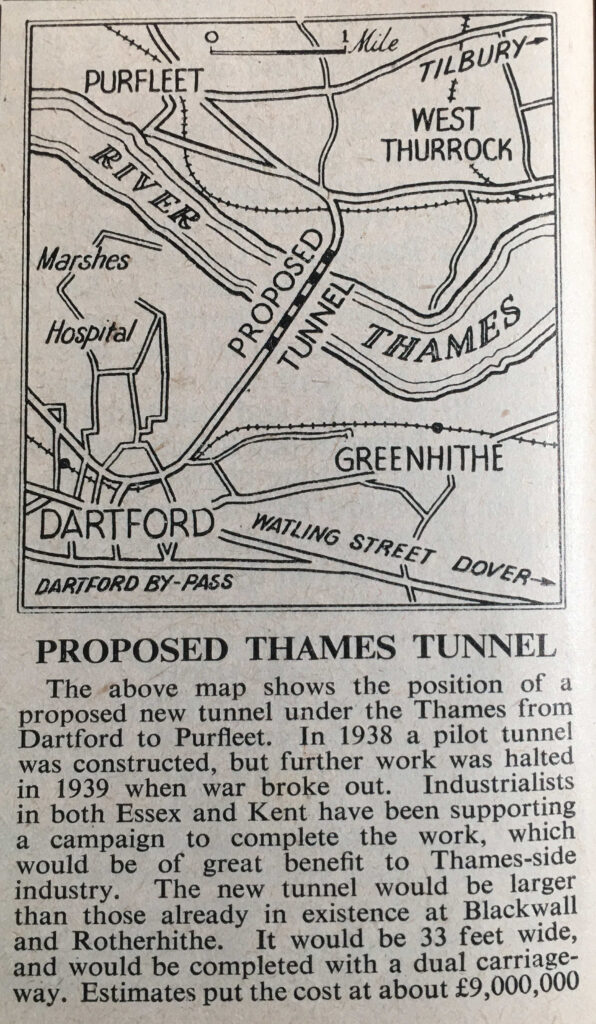

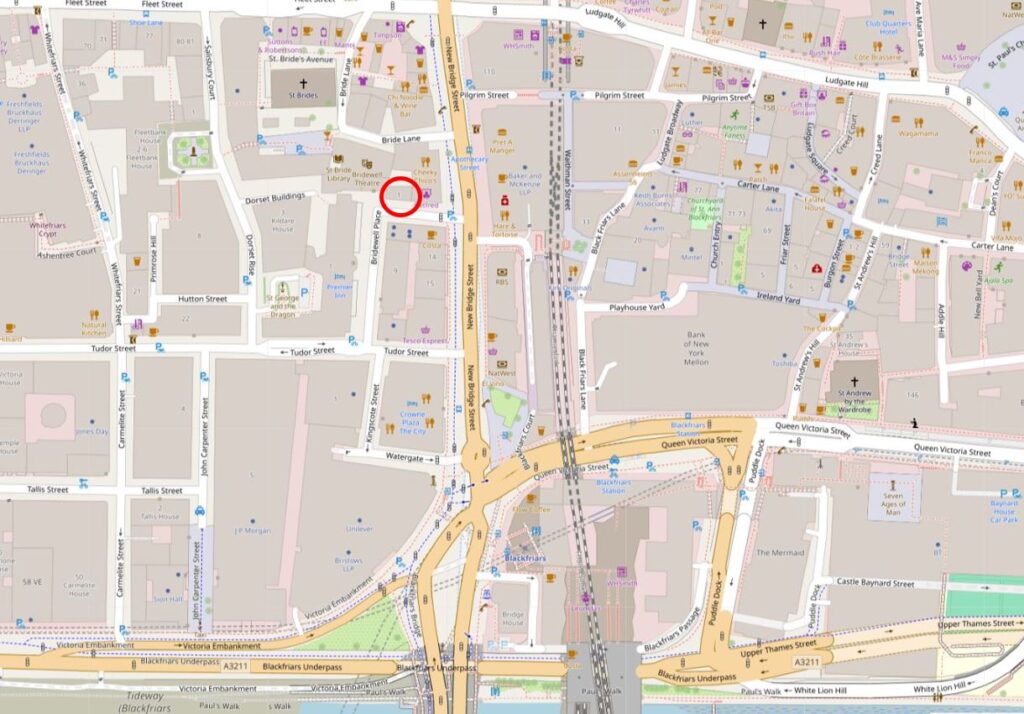

Tucked away in a corner of a page in the section on the Thames, there is a reference to a new infrastructure project that would become part of the most dominant transport method across the country, with the “Proposed Thames Tunnel”, which would become the first tunnel of what is now the twin tunnels and the bridge of the Dartford Crossing:

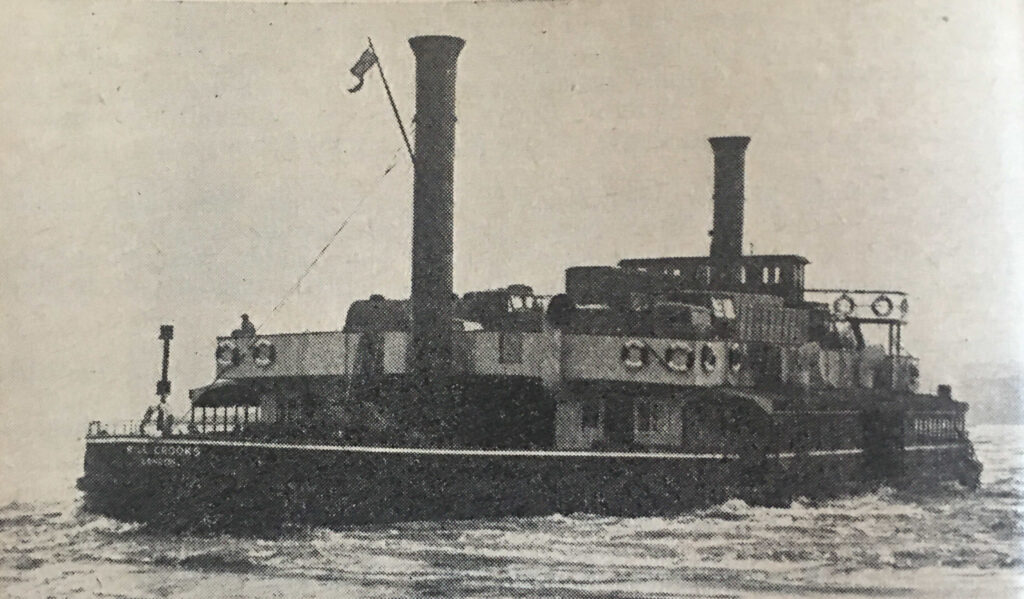

Although the proposed Thames tunnel would be a future method of crossing the river, other methods were in use, which are still in use today, such as the Woolwich Free Ferry:

The Woolwich Free Ferry had opened in 1889, and in 1954 was operated by four vessels of the type shown in the above photo, named, John Benn, John Squires, Gordon Crooks and Will Crooks. The vessel shown in the above photo is the Will Crooks.

Whilst the Thames supported the majority of London’s trade and industry, it was also a threat to the City, as the 1953 floods had so tragically demonstrated.

Although the 1953 flood was exceptional, London had suffered many minor flooding events, and newspapers hold very many records of these over the previous couple of hundred years.

Water would often break the embankment defences, as shown in the following photo, with the caption: “Firemen dragging kerb-stones to buttress the Embankment wall as water comes up at Lambeth Bridge during a Thames flood”:

The 1953 flood, along with the many minor floods, would lead to the construction of the Thames Barrier with the Thames Barrier and Flood Protection Act 1972 enabling the construction of the barrier which became operational in 1982.

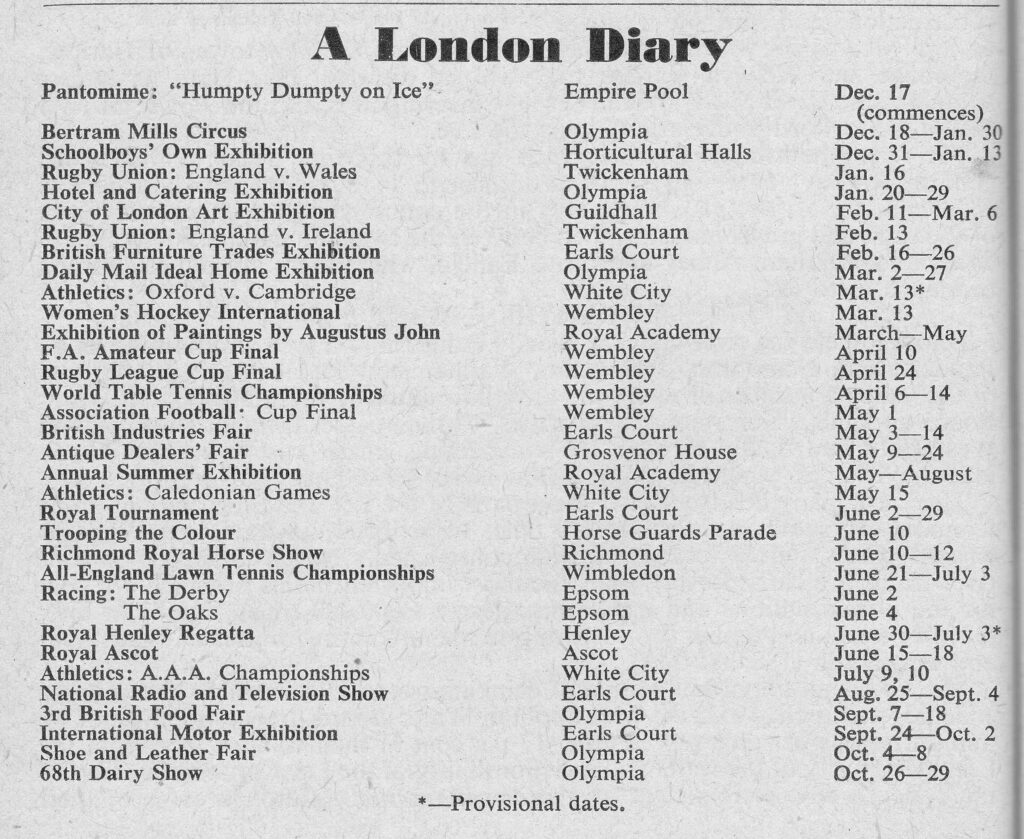

Between the sections on the Thames, and a brief section on new arrivals at London Zoo, the Year Book included a London Diary, detailing the dates of major events in the city during 1954:

There may not have been too much interest in the 1954 Association Football Cup Final (now known as the FA Cup), as there were no London clubs involved. In the 1954 final, West Bromwich Albion beat Preston North End 3-2.

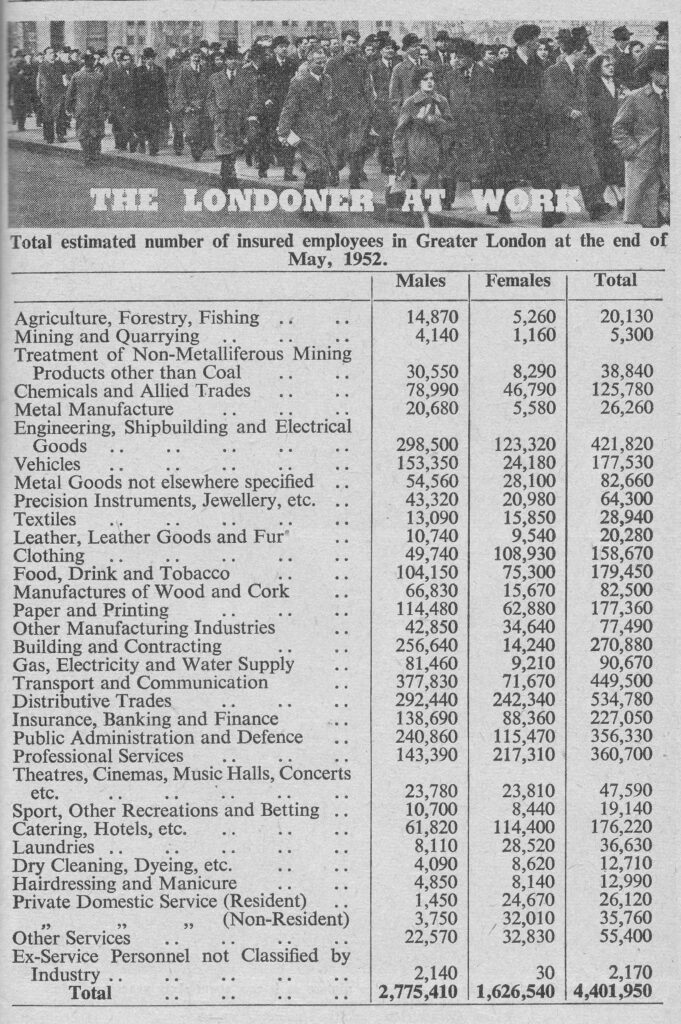

The Year Book includes a table titled “The Londoner At Work”, which includes a list of the types of work and professions, along with an estimate of the numbers employed in each:

Again, the table shows how London has changed in the last 70 years, with the types of job, and the numbers employed, very different today. At the time of the Year Book, the third highest number of employees, worked in Engineering, Shipbuilding and Electrical Goods. I do not know the equivalent number today, but it must be a very small number when compared to 1954.

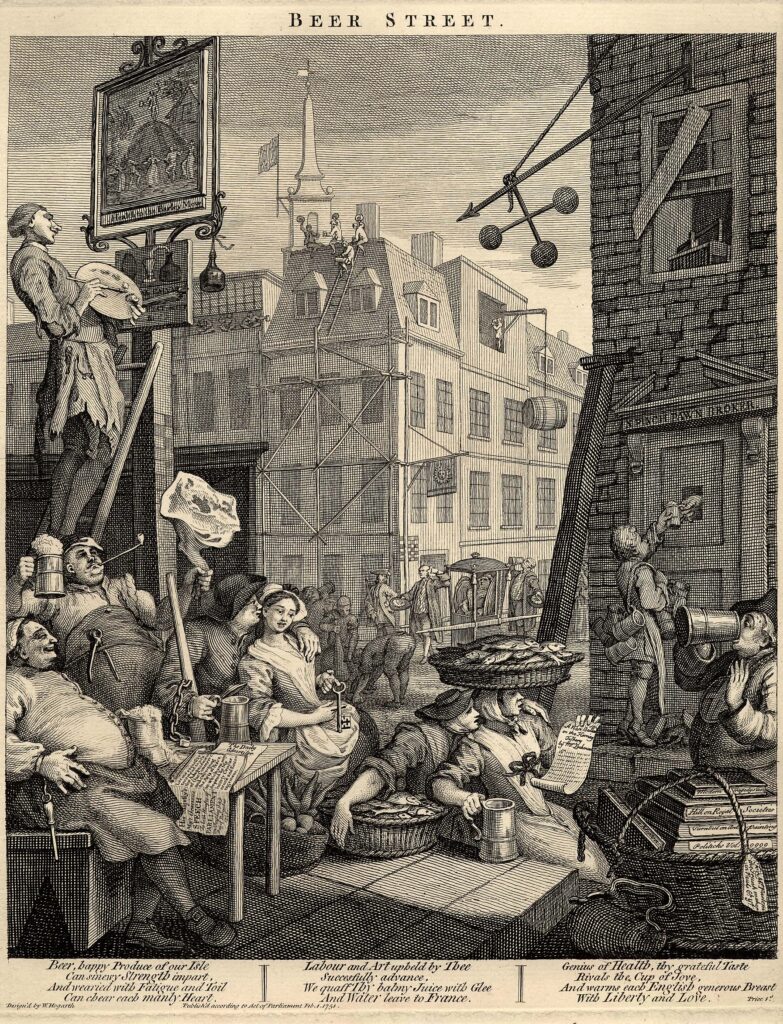

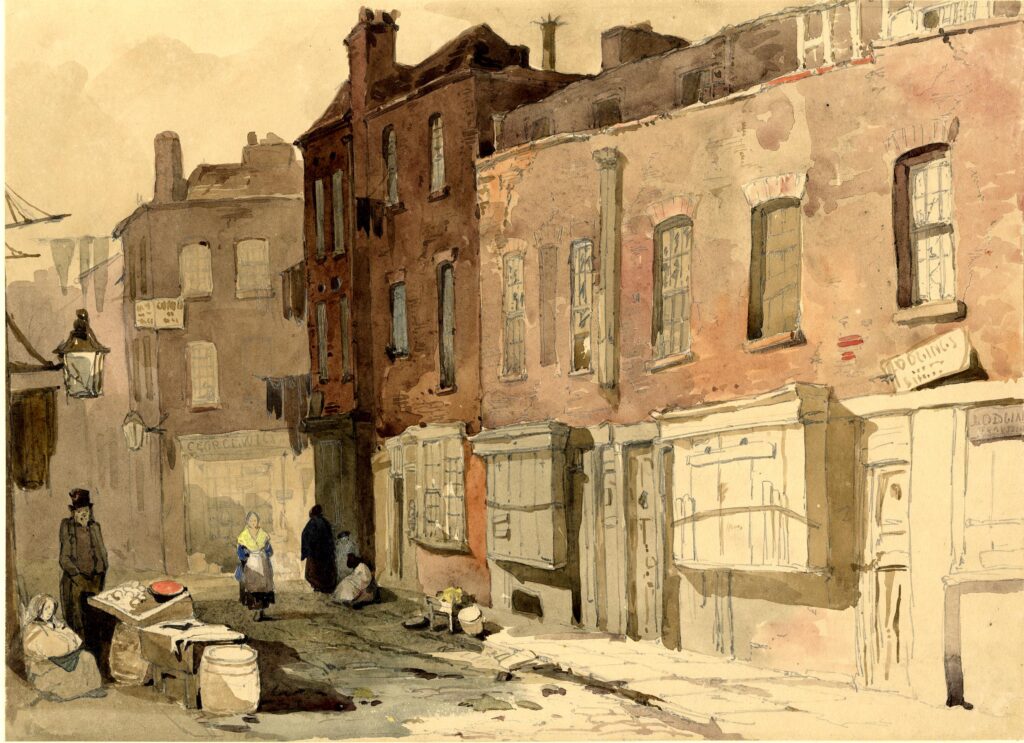

Then and Now photos have always been popular, and the 1954 Year Book included a number, showing how London has changed over the years.

The first is of Regent Street, where the caption to these two photos reads “Apart from the traffic, Regent Street has apparently changed but little – but look again. The buildings are different, and the street at the end seen in the upper picture taken in the 1890s is now gone”:

Followed by “The top picture shows the Strand, only 43 years ago. Bush House was not yet built, but a space has been cleared. Posters on the island site inform us that ‘Sweet Nell of Old Drury’ would be running at the New Theatre. Today, only the building on the left, and St. Mary’s church remain”:

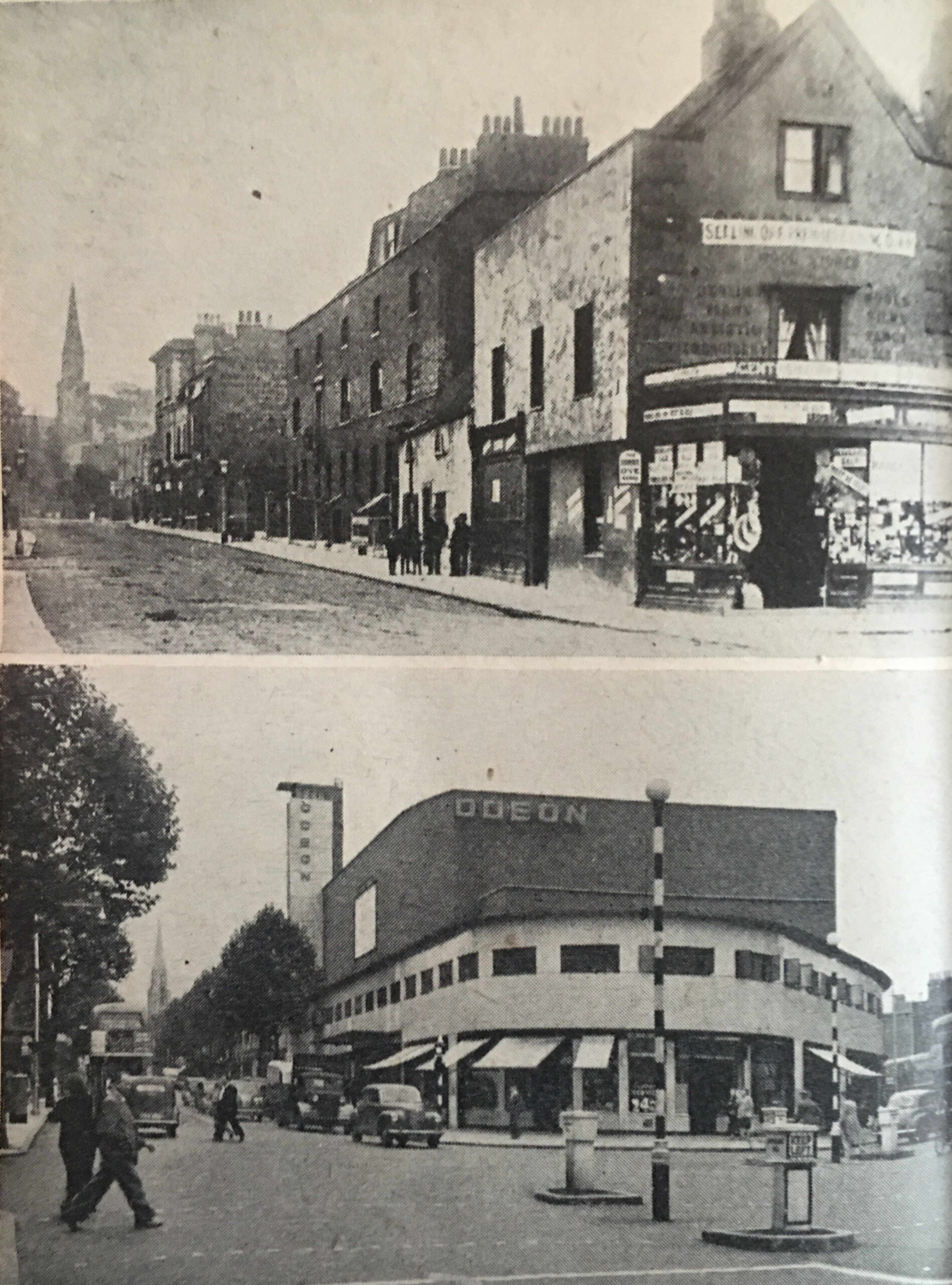

And finally “Selling off, premises coming down, says the notice on the shop in Camberwell in 1889. And down came the building, to make way for a theatre. Here, at the Triangle, Camberwell, was built the Empire Theatre in 1894. Today, that too has gone, and a modern cinema takes its place”:

The Odeon Cinema shown in the above photo was opened in 1939, however it closed as a cinema in 1975, with periods of temporary alternative use, along with being empty, until it was finally demolished in 1993. The site is now occupied by a Nando’s and flats. London keeps changing.

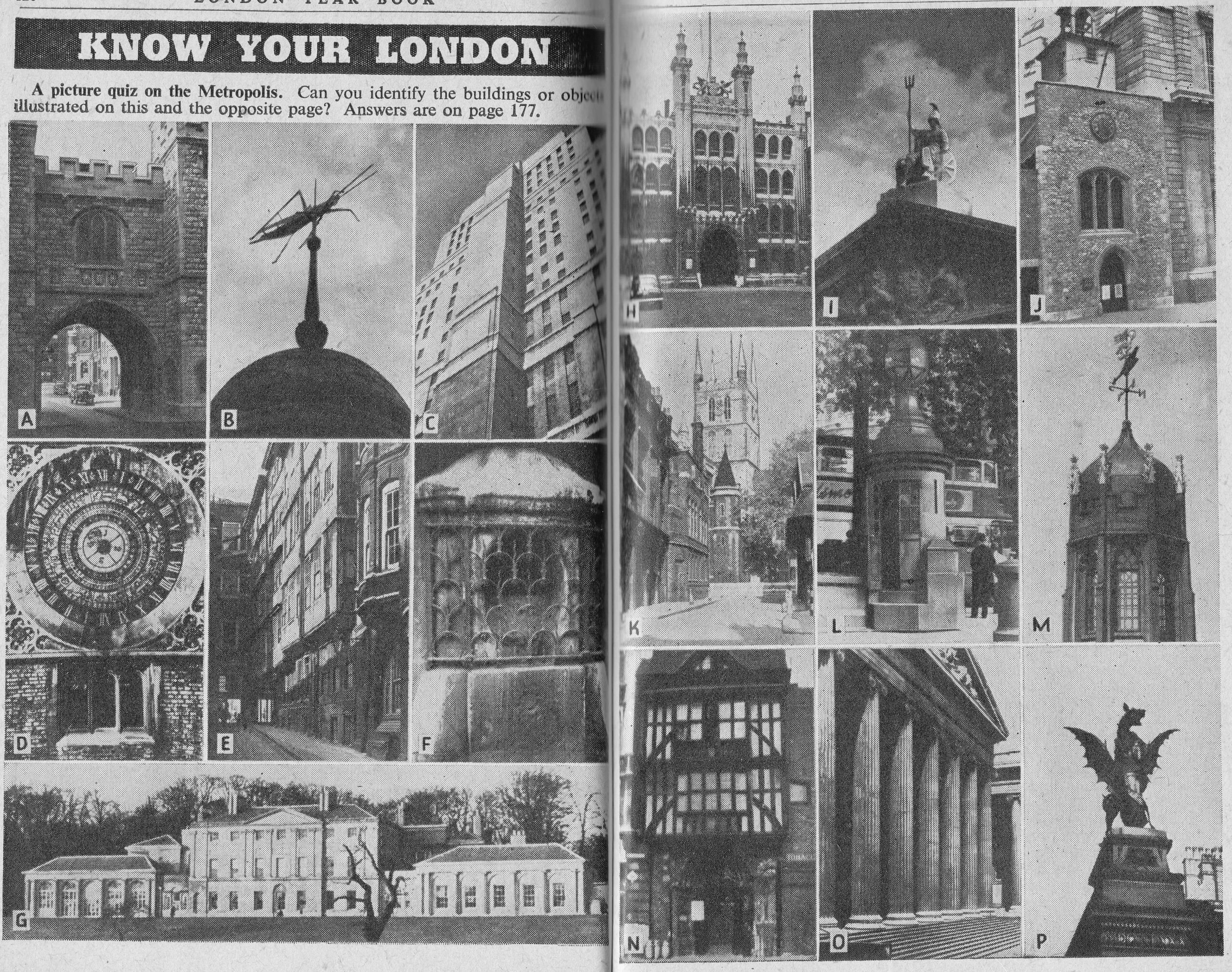

The Year Book included a “Know Your London” section, with a picture quiz of buildings and objects from across the city. Answers will be at the end of the post.

Although the Year Book contains a very large amount of data about London, some of it is partial and does not show a complete picture.

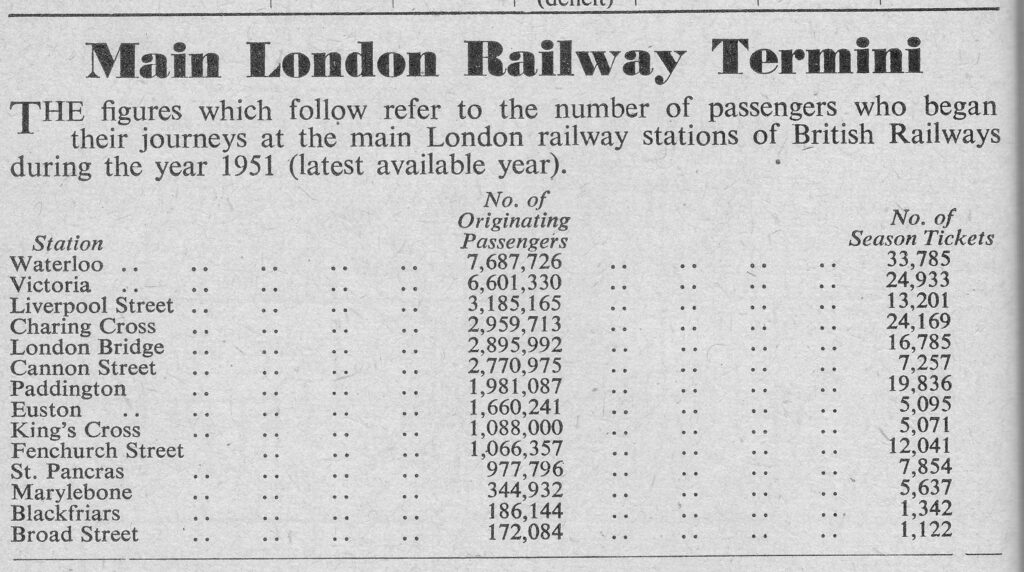

The Year Book includes the following table about passenger numbers at the main London railway termini. The numbers are of Originating Passengers, passengers who began their journey at the station, so does not show the overall number of passengers.

Presumably, to get an estimate of the total number of passengers I could double the figures in the table, as those who depart from the station may well return, and this would certainly apply to the large number of commuters, which I assume is what the Season Tickets figure covers.

Despite the gaps in the above figures, it does show that Waterloo was the busiest station by originating passengers in 1951, a position it would hold in overall passenger numbers for the following decades.

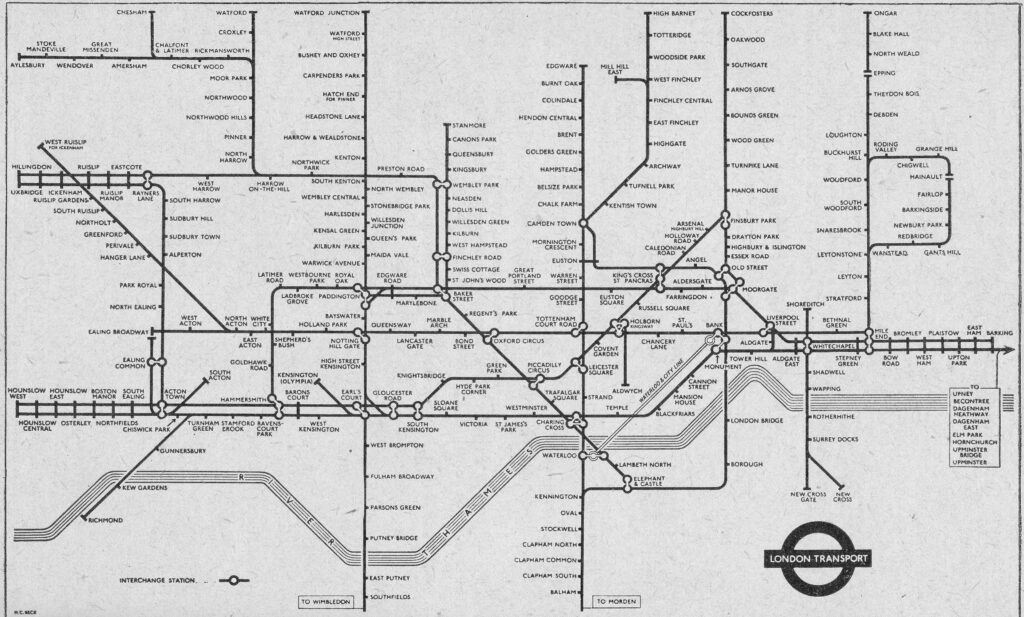

Any guide to London would need to include a map of the Underground network, and the 1954 Year Book included such a map:

The Victoria and Jubilee lines had yet to be built, and the Embankment Station is shown as Charing Cross, with Charing Cross Station shown as Trafalgar Square.

The Year Book has a vast amount of individual facts and figures, and it is interesting to compare with the same figures of today, however where comparisons are made, I have not had time to confirm the method of measurement is the same, but these figures do give an indication of change and of overall numbers, for example:

- London had a total of 80,683 hospital beds (compared to 20,746 today)

- The London Fire Brigade attended to 20,328 calls (I cannot find equivalent data, but in 2022 the LFB responded to 125,392 incidents, comprising 19,298 fires, 46,479 special services and 59,415 false alarms)

- The London Electricity Board was still changing over customer supplies from legacy DC and non-standard AC supplies to get all consumers on to the standard 230volt supply we use today

- In 1952, 8,307,345 telegrams had been sent

- There were 1,845,078 telephones in London

- 15,209 telephonists connected calls where automatic calls could not be made

- In 1952, 2,684,248,580 letters and packets had been posted, of which 99,294,832 had been sent at Christmas

- The City of London Police had 633 officers at the end of 1952, compared to 1,007 today

- The Metropolitan Police had 16,399 officers at the end of 1952, whilst today there are 34,184 officers (excluding community support and special officers)

- There were 121,411 registered aliens across London in 1952, the largest population coming from Germany which numbered 10,721

- There were 1,121 missing persons reported in 1952 with 35 cases outstanding at the end of the year

- During 1952, 15,684 stray dogs came into the hands of the Police and were sent to Dog’s Homes

- 570 people had been killed on London’s roads in 1952

- There were 4,020 taxi-drivers licensed by the Metropolitan Police

- The daily average of water supplied to consumers across London was 325,090,000 gallons, and the average consumption per head was 49.44 gallons, compared to 144.4 litres (31.76 gallons) per head in 2021/22 (I assume the higher number in the early 1950s was down to the amount of industry in London, which the city does not have today)

As with the 1953 edition, the London Year Book for 1954 is a fascinating snapshot of the city.

As far as I know, these books were only published for 1953 and 1954. I would love to be wrong, and find other editions.

Much equivalent information is made available online today, however whilst today there is the ability to provide much more detailed and granular levels of data, frequently a headline figure is obscured by the amount of detail available.

Information is also often scattered across various organisations as responsibilities for services has been devolved across both the public and private sectors.

A annual Year Book would be a brilliant summary of the state of London.

And with that review of 1954, can I wish you a very happy 2024, and close with the answers to the picture quiz from seventy years ago:

- A. St. John’s Gate, Clerkenwell

- B. Grasshopper on top of the Royal Exchange

- C. Senate House, London University

- D. Calendar Clock, Hampton Court

- E. Middle Temple Lane, leading up to Fleet Street

- F. London Stone, in the wall of St. Swithin’s church opposite Cannon Street Station

- G. Kenwood House

- H. Guldhall, City of London

- I. Figure of Britannia on top of Somerset House

- J. St. Ethelburga’s Church, Bishopsgate

- K. Southwark Cathedral

- L. One-man police station in Trafalgar Square. the lamp is from H.M.S. Victory

- M. The tower of Middle Temple Hall, surmounted by the Agnus Dei of the Temple

Regarding the one-man police station in Trafalgar Square and the lamp coming from H.M.S. Victory, I have never found any firm evidence for this, so whilst it may be true, it may also be one of those myths that gets retold about the city.