Tavistock Square is one of the many open spaces in Bloomsbury, built during the development of land owned by the Dukes of Bedford as London expanded north from the mid 18th to the early 19th centuries.

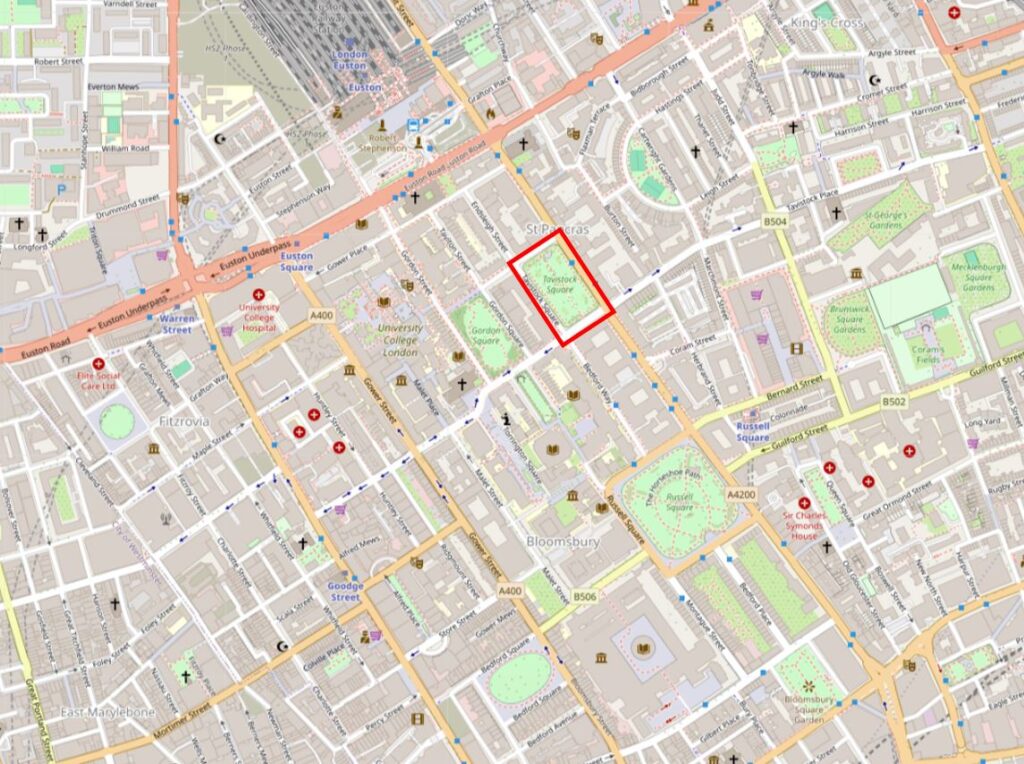

I have marked Tavistock Square with a red rectangle in the following map:

The name comes from the Duke of Bedford’s second title, the Marquis of Tavistock, a title created in 1694, and named after the grant of land belonging to Tavistock Abbey to the family.

As can be seen from the above map, Tavistock Square is one of a number of open spaces in a built up area. The Euston Road is just to the north, and the A4200 runs along the eastern side of the square, a busy road that carries traffic between the Euston Road and Holborn.

Euston Station is a short walk to the north.

Standing in places such as Tavistock Square today it is hard to imagine that a couple of centuries ago (a relatively short period in the history of London), all this was fields and pasture on the northern boundary of the built city.

An area crossed by tracks and walkways across the fields, streams and ponds.

Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows the northern limits of the city. Queen Square had recently been built, along with Bedford House, and Montague House is located where the British Museum can be found today. I have marked the location of Tavistock Square with the red rectangle:

Russell Square would be built just north of where Bedford House is shown (Russell is the family name of the Dukes of Bedford / Marquis of Tavistock), and the family were major landowners across this part of London.

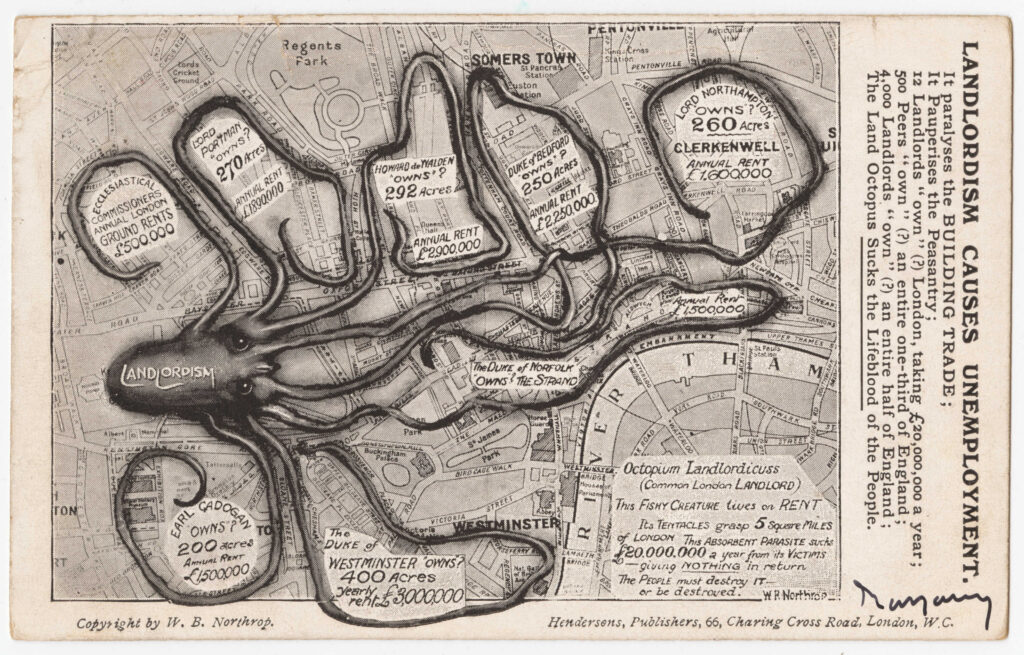

The Duke of Bedford and his landholdings featured in a map created in 1909 by William Bellinger Northrop and titled “Landlordism Causes Unemployment”.

Map from Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography and reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) Unported License

The aim of Northrop’s map was to show how “Landlordism” was strangling London, with large areas of the city being owned by the rich and powerful. Northrop claimed that the Duke of Bedford owned 250 acres, and that this estate produced an annual rent of £2,250,000.

Northrop claimed that Landlordism:

- Paralyses the building trade;

- It Pauperises the Peasantry;

- 12 Landlords “own” (?) London, taking £20,000,000;

- 500 Peers “own” (?) and entire one-third of England;

- 4,000 Landlords “own” (?) and entire half of England:

- the Land Octopus Sucks the Lifeblood of the People.

In many ways, this has not changed that much across the country, although in many instances the landed aristocracy has been replaced with very wealthy individuals, foreign investment, often state owned companies, and private development companies.

Tavistock Square was laid out in the late 18th century, and a terrace of houses along the eastern side of the square had been completed in 1803. These are believed to have been built by James Burton, a prolific London builder, and perhaps one of the most important since Nicholas Barbon.

The houses built by Burton in Tavistock Square had an unusual feature, where the staircase was configured to rise towards the front door, so when you went upstairs, you were walking towards the front of the house, with a landing at the front of the house, and the main rooms towards the rear, looking on small gardens at the rear of the houses, rather than the square.

These houses were demolished in 1938.

The following photo was taken from the southern part of the central gardens, looking north:

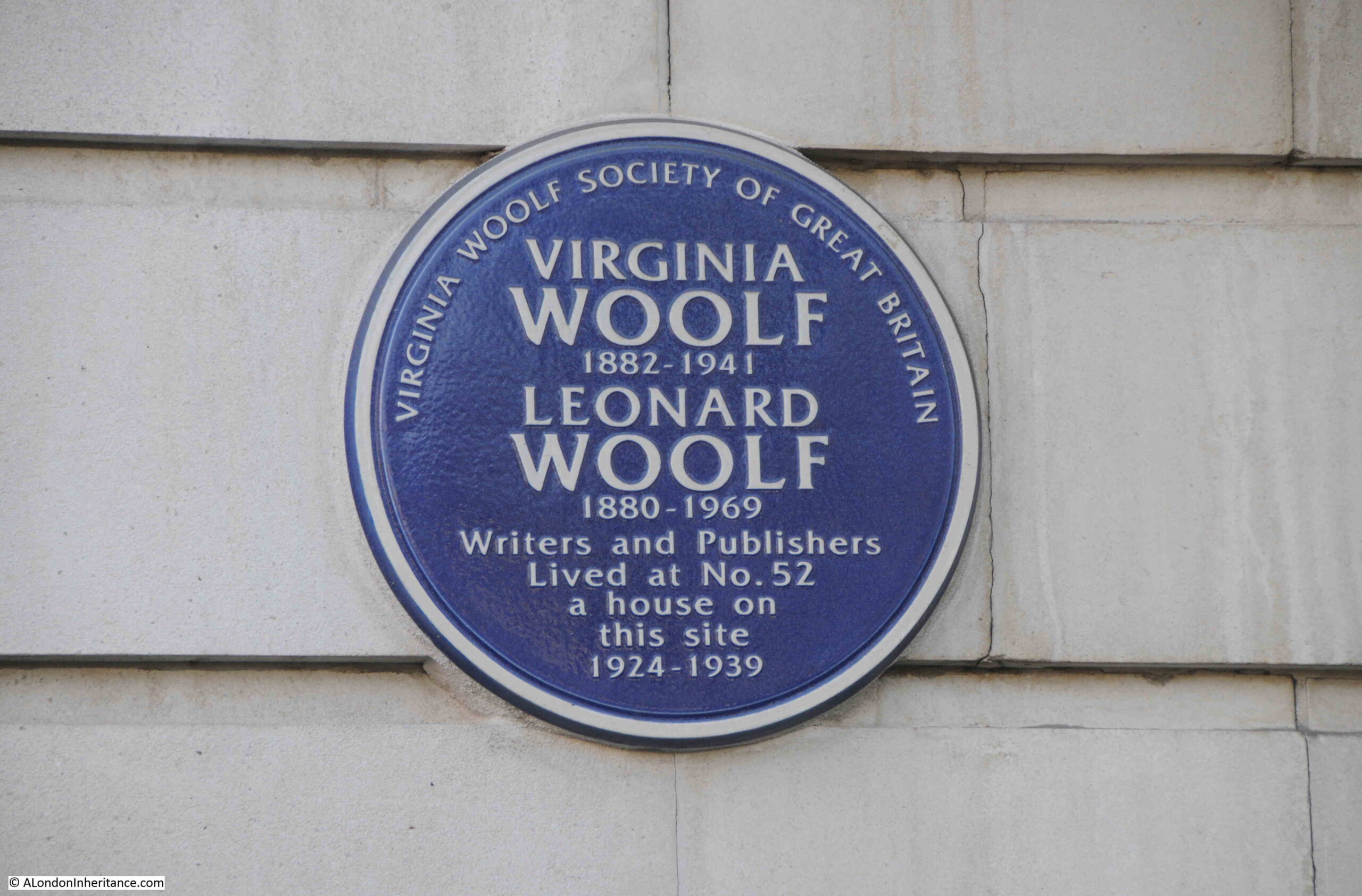

On the south west corner of the central gardens, we find Virginia Woolf:

Virginia Woolf, the writer, lived in Tavistock Square between 1924 and 1939, in a house along the southern side of the square, which was destroyed by bombing during the Second World War, indeed there was a considerable amount of bomb damage around Bloomsbury, which explains why many of these squares, and some of the surrounding streets, have lost their original terraces of houses, and why you often find a post-war building in the middle of an early 19th century terrace.

In the south east corner of the gardens, is a memorial to Louisa Brandreth Aldrich-Blake (1865 to 1925):

Louisa Aldrich-Blake was a pioneering surgeon, from a time when it was difficult for women to have such roles in the medical profession. She was Dean of the London School of Medicine between 1914 and 1925, a Consulting Surgeon at the Royal Free Hospital between 1919 and 1925, and a Surgeon to the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital between 1895 and 1925.

The memorial dates from 1926, and the base, seating and plinth were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, with the bust of Louisa Aldrich-Blake being by the sculptor A. G. Walker.

The monuments to two pioneering women sets the tone for the rest of the gardens, as they contain different memorials to the normal London square, and there is not an aristocrat in sight.

Walking along the central path in the gardens, to the north, and there is a Maple Tree which was planted in 1986 by the League of Jewish Women:

In the centre of the square is a memorial to Mahatma Gandhi, the lawyer and campaigner for India’s freedom from British rule:

The memorial looks recent, but dates from 1968, and was unveiled by Prime Minister Harold Wilson in May of that year. It is Grade II listed, with a base of Portland Stone, with the bronze figure of Ghandi by the sculptor Fredda Brilliant.

The relevance of Tavistock Square to Gandhi is that he attended University College London in Bloomsbury where he studied English literature, and also learning law at the Inner Temple.

Ghandhi’s approach to non-violent protest is reflected in many of the memorials in Tavistock Square, such as the International Year of Peace shown above, and also with another tree, the Friendship Tree planted in 1997 by the High Commissioner for India:

And another tree was planted in 1967 in memory of the victims of the atomic bomb dropped on the city of Hiroshima in Japan:

At the northern end of the gardens is a large stone memorial which dates from 1994 and is to Conscientious Objectors, “To all those who have established and are maintaining the right to refuse to kill“:

The Tavistock Hotel is a large, red brick building, that occupies the whole southern part of the square:

The space occupied by the hotel was originally a run of terrace houses. but these were badly damaged during the war. The remains of these buildings were demolished, and the Tavistock Hotel was built in 1951, and became the first hotel built in London after the war.

One of the houses that once occupied the site, was the one where Virginia Woolf and her husband lived whilst in Tavistock Square, and to the side of the entrance to the hotel there is a plaque recording her residence on the site:

All sides of Tavistock Square suffered bomb damage, with the southern, eastern and northern sides being completely rebuilt.

The western side of the street suffered bomb damage at the ends of the long terrace, leaving the majority of the terrace undamaged:

This lovely stretch of terrace houses was completed in 1824, and were built by Thomas Cubitt. Although Burton’s terrace on the eastern side of the square were demolished long ago, they were described as being inferior to Cubitt’s terrace, and the terrace is well built, with a pleasing symmetry along the length of the terrace, which is in an Italianate style, with Ionic columns in rows of four, running the height of the terrace from above the ground floor to the balustrade and roof line.

A number of the houses in the terrace are Grade II listed.

Although the terrace looks as if it is comprised of individual terrace houses, the terrace is owned by the University of London and University College of London, and the interiors have been modified and combined to accommodate this new use.

Along the terrace, at number 33, is a plaque between the two ground floor windows:

The plaque records that Ali Mohammed Abbas lived in a flat in the house between 1945 and 1979.

Abbas arrived in London from India in 1945 to study law and became a Barrister. Following the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan on the 14th of August 1947, Abbas used his flat as an unofficial Pakistan Embassy until the new country set up a full embassy in London.

After Pakistan became an independent country, Abbas remained in London and continued work as a barrister. He also helped set up twenty eight schools all over the country to help Pakistanis who had arrived in the country, speak, read and write in English.

The house in Tavistock Square was his home until his death in 1979.

At the north western corner of the square is another red brick / Portland stone building – Tavistock Court:

Tavistock Court is an apartment block, built between 1934 and 1935. It did suffer some light damage during the war, but this was repaired, and the building today looks impressive in the sun, hopefully as the original architect intended.

Next to Tavistock Court, along the north side of Tavistock Square is Woburn House:

This a post war building, due to bomb damage to the building originally on the site.

The building is owned by Universities UK, the organisation that represents 140 member universities across the UK, and is another example of the concentration of educational establishments across this part of Bloomsbury.

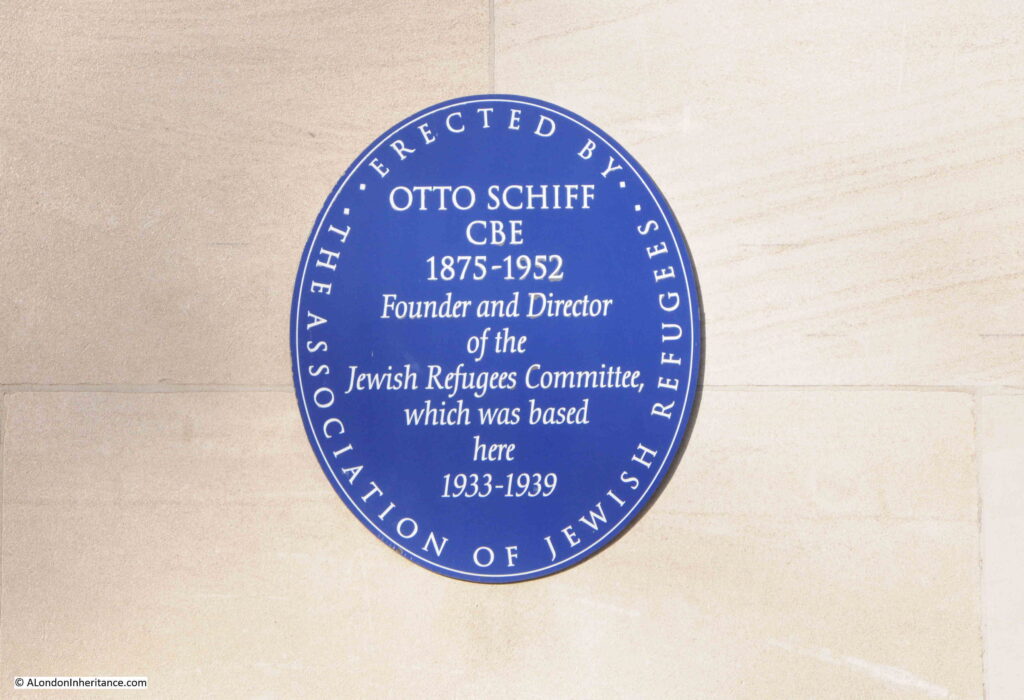

There are two plaques on the corner of the building which can just be seen in the above photo. The one on the left is to Otto Schiff, who was the founder and director of the Jewish Refugees Committee, which was based in a pre-war building on the site:

Otto Schiff and the Jewish Refugees Committee were responsible for persuading the Government to allow Jewish refugees to enter the country, and that they would be funded by Jewish organizations, charities and individuals. The committee also helped with the travel arrangements of transporting refugees from Germany to the UK, and their housing and general support after they had arrived.

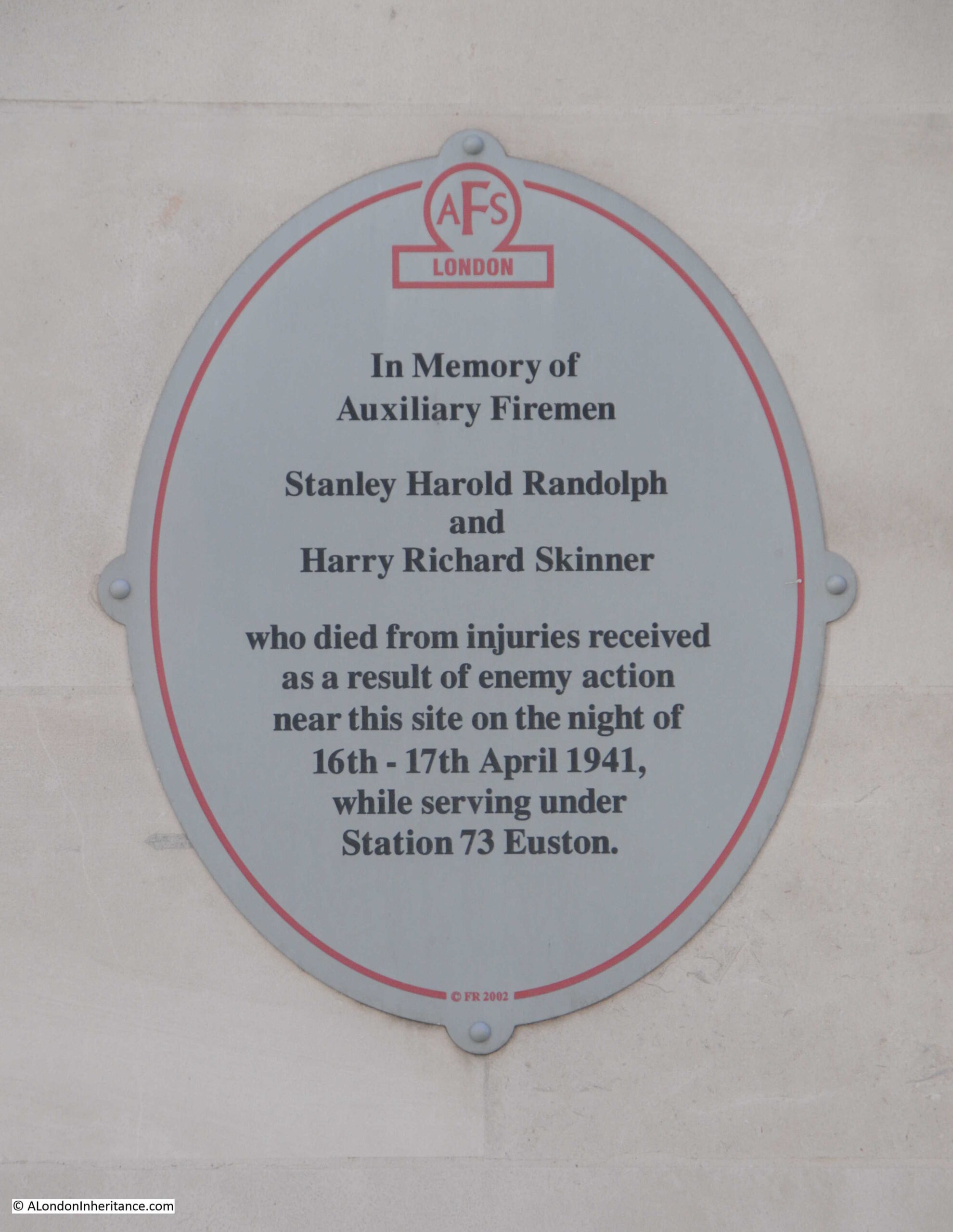

The plaque illustrates the dreadful impact on the Jewish population of Europe before and during the second World War, and the second plaque on the corner of the building illustrates another way the war impacted London:

There was a significant amount of bomb damage around Bloomsbury. Whether this was trying to target the railway stations along the Euston Road, or just the indiscriminate bombing of London, I do not know, but the plaque does provide a reminder of those in the fire service across the City.

The Auxiliary Fire Service was formed in January 1938 to provide a large uplift in the number of fire fighters to assist the full time fire service. Those who staffed the Auxiliary Fire Service were usually those who were too young or too old for service in the armed forces,

Although being an auxiliary force, they faced the same dangers as the main force, and Stanley and Harry were two of the 327 fire fighters who lost their lives across London during the war.

Standing next to Woburn House, and looking at the north east corner of Tavistock Square, we can see the northern part of the buildings of the British Medical Association:

The rest of the BMA building is shown in the following photo taken from the gardens at the centre of Tavistock Square:

BMA House is an impressive building, and the organisation have occupied the building since 1923 when they purchased the lease. The BMA had originally been based in the Strand.

BMA House was originally designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for a very different organisation, the Theosophical Society, as the future site for their offices and temple. Construction started in 1913, however the First World War intervened and the parts of the building that had been completed were taken over by the Army Pay Office.

When the war ended, the Theosophical Society appears to have run out of funds to complete construction, and the site was taken over by the BMA. The Theosophical Society are still based in London, but at much smaller premises at 50 Gloucester Place.

Sir Edwin Lutyens was reemployed to complete parts of the building and the interior, and to finish the overall site, Cyril Wontner Smith completed the central entrance from Tavistock Square between 1928 and 1929, and Douglas Wood worked on extensions to the overall building between 1938 and 1960.

The building is Grade II listed.

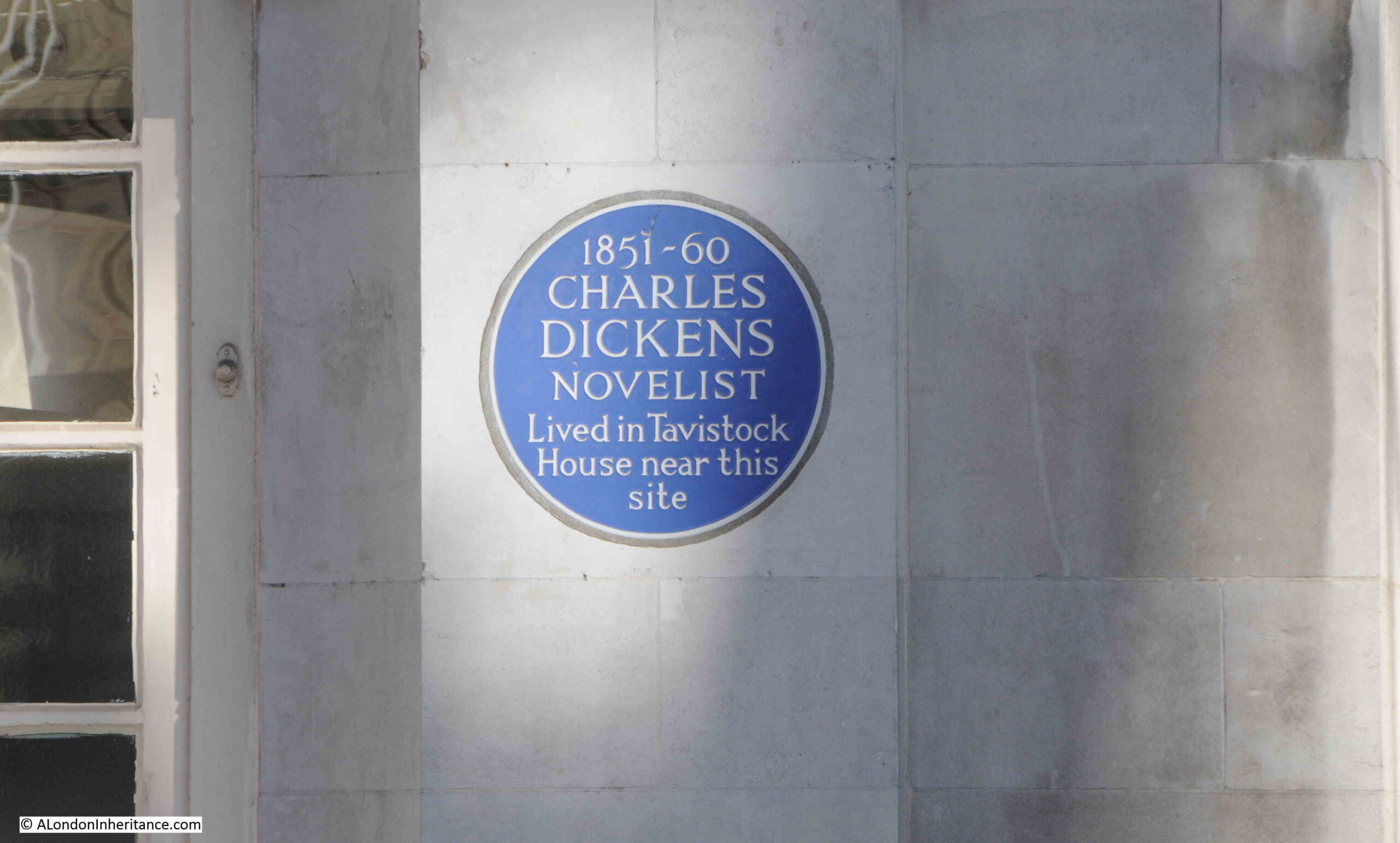

There is another plaque on the BMA building, recording that Charles Dickens lived in a house near the site of the plaque between 1851 and 1860, his last London home before moving to Gads Hill in Kent.:

So there is much to discover in Tavistock Square, where just over 220 years ago there were just fields.

Ah! Great memories. I used to walk through the square several times a day for almost three years and there was always something different to see.

An interesting read on a Sunday morning, so much history.

Happy Mothers Day!

Hi,

Tavistock Square was on my many walks from Cumberland Market to Gamage’s (Holborn Circus) in the 1950s, specifically to visit their toy department. Tavistock Square was the last place I remember a hand-turned barrel organ actually being played in a London street – though I don’t remember a monkey!

Ian

I don’t think I’ve seen an AFS plaque before. Are there others? If not, I wonder why Mr Randolph and Mr Skinner are memorialised here. Did they show especial bravery, or were their names picked at random to represent all the auxiliary firefighters?

And of course, in July 2005 13 passengers were killed outside the BMA when a suicide bomber detonated a bomb aboard a no. 30 bus.

One of those people was my friend and work colleague, Giles Hart. He got on the wrong bus outside Kings Cross, he was trying to get to the Angel, where we worked at the time. Meanwhile, I was at Liverpool Street when the terrorist blew up the train there. A dreadful day that I will never forget.

My condolences. So many lives senselessly lost that day.

Yes, alas a chance to remind us of vital part of London’s history in the fight against tyranny and oppression was missed – and to be honest, when I saw the title of the post I assumed that is what it was going to be about and a mere mention of it would have rounded off perfectly the squares history. The BMA building was mentioned, but this memorable photograph from 7/7/05 was not shown <>

to illustrate that BMA House staff were first-hand witnesses and helpers in the July 7 London bombings.

The bomb that destroyed the number 30 bus in Tavistock Square exploded directly outside BMA House, killing 13 and spreading “blood and flesh on the walls of BMA House,” wrote Kieran Walsh (BMJ 2005;331:127). Physicians in the building helped the wounded before ambulances arrived. BMJ editor Fiona Godlee commended staff on their efforts to produce the journal without interruption from a contingency site as the “best answer to those who would tear our world apart” (BMJ 2005;331:0-g).

Your colleague Giles Hart sounds, from his Wikipedia page, like he was a good chap. A dreadful day indeed. Sorry for the loss of your friend, and apologies for the delay in replying.

My Dad was an auxiliary firefighter during WW2 based at Whitefriars fire station, not too far from the memorial plaque to the two firemen who lost their lives. He was part of the team that helped protect St Pauls Cathedral, that was instrumental in fighting fires nearby to prevent its demise. Working during the blitz, they had to fight fires while the bombs were falling. Dad never talked about it but, from what I’ve read, it must have been a harrowing experience. As always, thanks for another interesting post.

The Landlord’s map was fascinating. The landlords may change but the end result stays the same !

An interesting area of London which retains an aura of times gone by.

Thank you.

A really interesting and informative article on Tavistock Square which I thought I knew well. I was born in 1939 in Holborn in Boswell St formerly Devonshire St, and grew up there. After WWII my sister was housed in Tavistock Square in property requisitioned by the Borough Council.

I never realised there was so much to see there although some of it is after my time.

I am a member of a Facebook group called Vintage Holborn and would like to share this there if you have no objection.

Hi David – yes, very happy for the post to be shared.

Great piece of information although I have worked in and around all theses squares it’s interesting information like this that we sometimes ignore. Many thanks

What an excellent post! Just to say that the aid to Jewish refugees extended not just to Germany but Austria after the Anschluss: including my grandparents.

One of the buses blown up in the July 7 bombings in Tavistock Sq might be worthy of mention? Many of the injured were on it having been turfed out of the Tube.

Good article tho.

Thank you once again for a very interesting article. I grew up in Bedford Way, which leads off Tavistock Square. We lived in a line of terraced Georgian houses on the west side of the street, an extension of the line of similar houses bounding the west side of the Square, all belonging to London University, who let them as domestic accommodation during the post-war housing shortage while they saved-up to tear them down in the Sixties and replace them with The Bedford Way Building, a vast shell of concrete and glass. The Bomb Damage map in the London Picture Archive shows Bedford Way as Upper Bedford Place, its original name; we lived in the houses coloured orange (“General blast damage; not structural”) on the map. There were three gaps on our side of the street, direct hits by the Luftwaffe, or else very near misses, which composed our frighteningly dangerous playgrounds and were later very useful as car parks, reflecting both our increasing affluence and mobility, and the recovery of the tourist industry in that area. In those days, parts of London resembled very strongly the news reports presently emerging from Ukraine. Tavistock Square was a lovely oasis of greenery, with sycamore, horse chestnut, and the abundant London plane, separated by shrubs and bushes, and beds of annuals, all maintained by the apparently full-time staff of keepers. You mentioned the memorials in and around the Square; I’m pretty certain that, back in the Sixties, there was also a sapling, possibly a flowering cherry, with a small sign declaring that it had been planted by Jarwahalal Nehru, Prime Minister of India, in memory of Mohandas Ghandi, of whom there is now also a statue in the Square. The area has a strong literary history, ranging from Mary Shelley in Marchmont Street to Virginia Woolf and Charles Dickens in Tavistock Square, the whole of the Bloomsbury Group in nearby Gordon Square, and T.S. Eliot, in his office at Faber & Faber, in Russell Square, at the far end of Bedford Way. It was a pleasant, peaceful place to grow up; I hope that it still is.

A post script to the various other comments on the 7/7 bomb which went off on a bus in Tavistock Sq. There is a memorial in the gardens to those that died in the bombing – and there was a plaque marking the location of the bus when the bomb exploded on the railings outside BMA House – but I haven’t checked to see if it is still there. It is disappointing that you discussed the other memorials and plaques in the square – but did not mention these ones.

I was driving through Tavistock Square that morning, and must have missed the bomb by a few minutes. It was a very frightening day in London, and one I still remember.

Thanks for this–I’m now fully up to speed on a square about which I knew little.

Several comments on the terrible events of 2005.

The link below, beautifully written at the time by novelist John Lanchester, sets it in context.

I find it ironic that the tree memorial to Hiroshima is only ~400 m from where the idea for the bomb was born.

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/12/july7.features11