A walk along College Hill in today’s post, but first, if you would like to come on one of my walks, a couple of places have just become free on two of my final walks until late next spring next year. Details and links are:

College Hill is a short street that runs from Cloak Lane to College Street, to the west of Cannon Street Station in the City of London.

It is only 238 feet in length, but within that distance there is a considerable amount of history and four City of London plaques commemorating people and places within the street. I cannot yet confirm, but I suspect this is the highest number of plaques in such a short street.

This post will explore the street based on the stories that the plaques tell, and also hopefully show some of the difficulties in being able to be certain of the truth, and that whilst the sources on the Internet require a degree of scepticism, this also applies to many written books on the history of London.

I will also find a plaque that appears to commemorate someone’s burial before he was actually dead.

So, turning into College Hill from Cloak Lane in the north, the first plaque is to:

Turners’ Hall

The first plaque along is on the left of a very ornate doorway on the east side of College Hill:

Recording that “On or near this site stood the second Turners’ Hall. 1736 to 1766”:

Turners’ Hall was the home for only 30 years of the Worshipful Company of Turners.

Members of the Tuners’ were those who specialised in wood turning on a lathe, and whilst this would have included the manufacture of furniture, a key product of the Turners’ appears to have been wooden measuring vessels, a device that would hold a set quantity of liquids such as wine or ale, and therefore able to show that an expected quantity (such as a pint or a quart) was being provided.

The trade of a Turner seems to date back many hundreds of years. According to “The Armorial Bearings of the Guilds of London” by John Bromley (1960):

“In 1310 six turners were sworn before the mayor not to make any other measures than gallons, pottles and quarts, and were enjoined to seize any false measures found in the hands of others whether free of the City or not.”

The problem with false measures was still a problem a couple of hundred years later, when in 1547 Turners were again summoned before the mayor and ordered to make only measures which conformed to the standard.

The mayor is still indirectly responsible for measures in the City of London, although rather than being hauled up before the Mayor, today it is the City of London Corporation Trading Standards team that manage this, and the sale of ale is still on their agenda as they have a web page dedicated to the Pub trade within the City of London and “Was your pint a short measure?”.

In 1604, King James the 1st granted the Turners’ their first Royal Charter.

The first Turners’ Hall was in Philpot Lane, off Eastcheap, where the company leased a mansion in 1591.

The Turners’ occupied this hall until 1736 when they had o leave their Philpot Lane location due to the landlord and the legal representative of the landlord’s estate both going bankrupt, apparently as a result of the South Sea Bubble.

The hall in College Hill was basically a merchants house. It was small, so did not have room for large, formal dinners, and at the same time the trade of the Turners’ was in decline, so in 1756 the building was let, and the Turners’ finally sold the building in 1766.

Today, the Turners’ do not have their own hall and now use halls of other City companies for their formal functions.

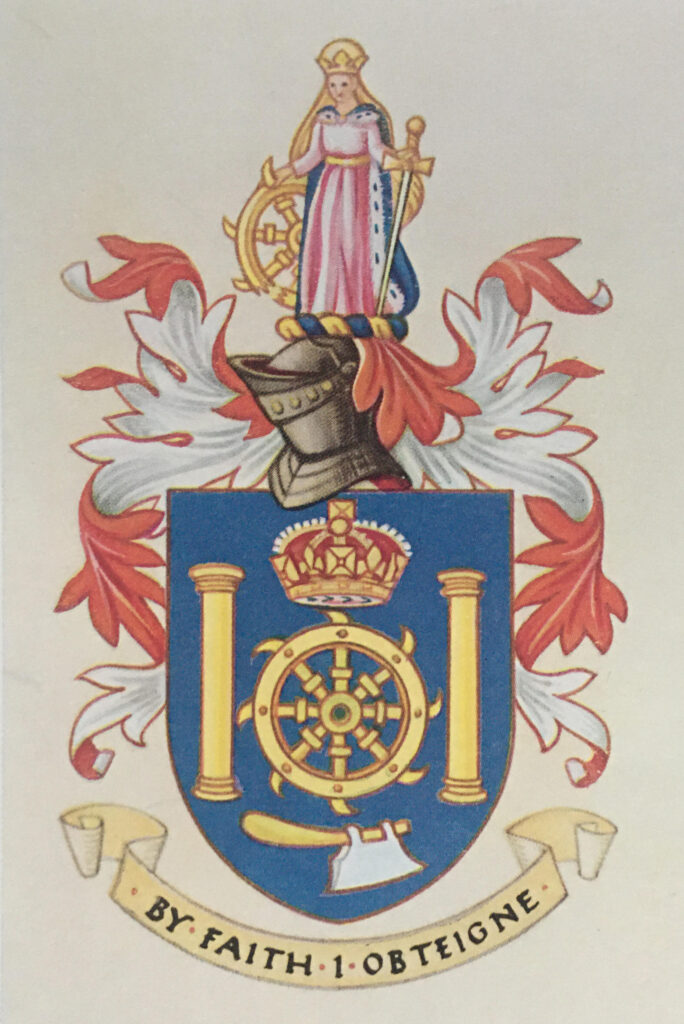

The Arms of the Turners’ are shown below:

The hatchet at the bottom and the columns on either side represent tools of the Turners’ craft, however the wheel in the centre has a much more gruesome origin.

It is a torture or execution wheel, also known as an execution wheel. It was used to break the bones and execute those convicted of crimes such as murder, and was also the device intended for the execution of St. Catherine of Alexandria in the early 4th century, by the Roman emperor Maxentius for converting people to Christianity.

Allegedly, when Catherine touched the wheel intended for her execution, it broke into many pieces, although rather than being set free, she was then beheaded.

“The Armorial Bearings of the Guilds of London” provides the following regarding the link between the Turners’ and St. Catherine:

“Because of her eloquence and learning St. Catherine is generally regarded as the patroness of students and philosophers, but she has also, as a result of her emblem, been adopted as the tutelary saint of wheelwrights and mechanics. Whether the emblem was used by the Turners’ on account of its traditional use by other similar crafts, or whether the Company was originally founded as a fraternity with vows to St. Catherine has not been determined.”

Catherine appears at the top of the Turners’ arms.

St. Catherine also gave her name to the firework known as a Catherine Wheel, so if you see one of these spinning round on November the 5th, recall that the origins of the name go back to an instrument of torture and execution and a 3rd century saint.

The plaque is on the far left of the following rather intriguing building:

Two massive entrances lead to courtyards behind. The doorways have impressive sculpture above.

This is number 22 College Hill and the building is Grade II* listed. The Historic England listing details are:

“Circa 1680 probably by Nicholas Barbon. Double gatehouse with inexplicably grand stone front now painted. 2 principal storeys. 2 round arched entrances with double gates and wooden tympanum. Bolection moulded surrounds and segmental pediments on carved brackets with richly carved ornament above each arch. Circular windows above with carved surrounds. Small shop inserted in centre with square and round arched windows over. Plain parapet. Rear of red brick (partly rendered) with wooden eaves cornice to tiled roof. Dormers. Central part set forward but whole much altered.”

I like the comment “inexplicably grand stone front” in the listing. The shop mentioned in the listing in the centre is now a restaurant, the India, and photos on their website show the restaurant is within a long, brick arched room, rather like the arch under a railway viaduct, which looks very unexpected when compared to the front of the building.

The entrances on either side of the building lead through to a courtyard and offices at the rear:

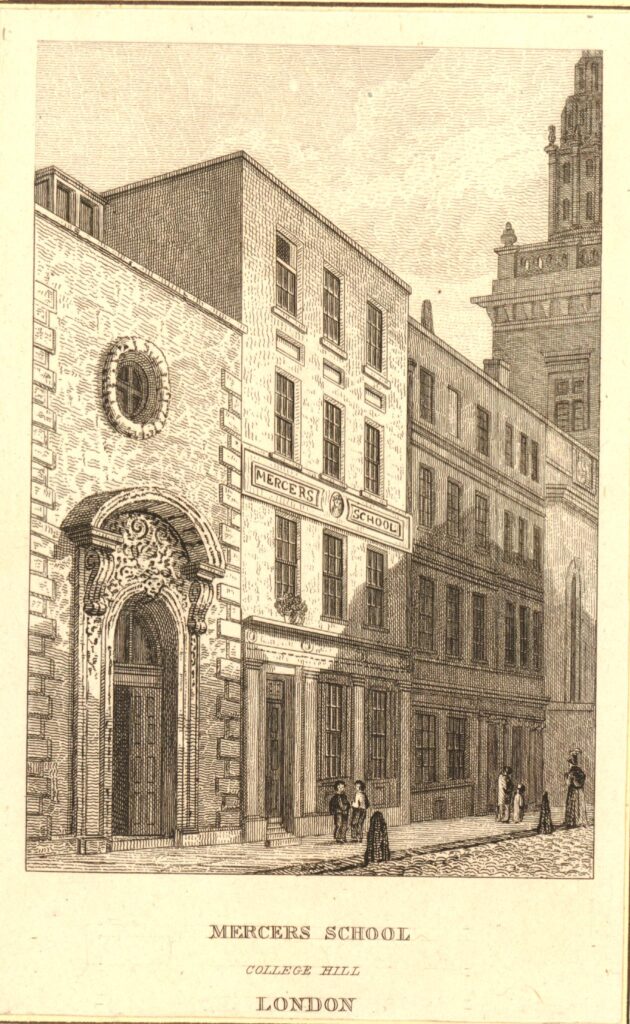

The following print dating from 1837 shows one of the entrances to the building, along with the building next along the street, which has a sign above the first floor windows stating that it is the Mercers School ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The Mercers School dates from 1542, and was in College Hill from around 1805 until the school moved to High Holborn in 1894.

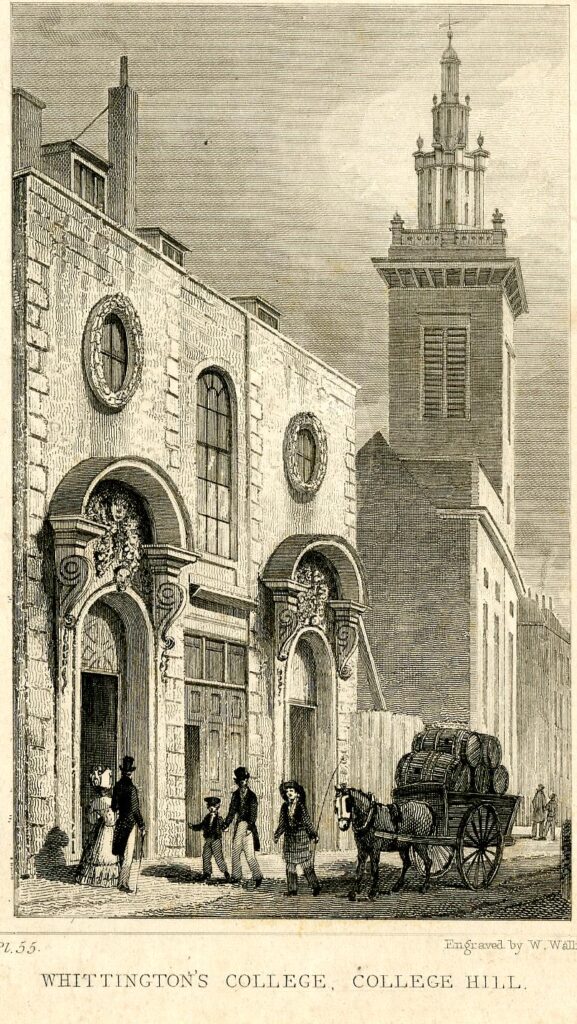

There is another print which shows the building, but adds some confusion, The following print is dated to between 1829 and 1831 and is titled “Whittington’s College, College Hill” ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The text on the British Museum collection website for the photo reads “View of Mercers’ School, founded by Whittington, c.1419, rebuilt c.1668; a cart laden with barrels stands outside the grand arched entrances to the college, a tower rises in the background.”

The text states that it is a view of the Mercers’ School, however the previous print shows the school in what is the empty plot of the above photo, so I wonder if the school originally moved into the building with the ornate entrances before a purpose built building was completed next door.

The text also states that Mercers’ School was founded by (Richard) Whittington c1419, however according to the Mercers’ School History, the school was started in 1542, over one hundred years after Whittington’s death.

There was though a Whittington College in College Hill, however it was dissolved in 1547 during Henry VIII’s dissolution of religious establishments. It was revived after his death by Mary, but finally wound up during the reign of Elizabeth I, so long before the building was constructed in 1680.

So the British Museum text appears to have errors, and whoever published the print of the building appears to have wrongly assumed that it was Whittington College, when by the time of the print the Mercers’ School was in College Hill.

The House of Richard Whittington

At numbers 19 to 20 College Hill is another Grade II listed building, dating from the mid 19th century:

On the left of the building is a plaque which states that “The House of Richard Whittington Mayor of London Stood on this Site in 1423”:

There has been much written about Richard Whittington, and many of these stories are myths. There was no cat (this was added centuries later), he was not poor, and whether he turned again as he was leaving the City to the north is probably unlikely.

Where he did have a challenge is that he was the younger son of Sir William Whittington, from Pauntley in Gloucestershire, and being a younger son, he would not have inherited his father’s wealth and lands.

On his arrival in London, he was apprenticed to a mercer, and gradually grew a reputation as a successful trader and also sold to the King. Between 1392 and 1394 Richard II purchased around £3,475 worth of goods from Whittington. He exported wool and also lent money to the King, all activities which built his wealth and reputation within the royal court.

His future reputation would be sealed when he became Mayor of London. It was his money lending, friendship and loyalty to the King, Richard II which enabled this, as in 1397 the City of London was being badly governed.

The King confiscated much of the City’s land, and selected Richard Whittington to be Mayor of the City, a choice which was confirmed by a vote of those eligible to vote within the City of London.

He appears to have been liked by the people of London, he carried out a number of improvements to the City, which apparently included rebuilding parts of the Guildhall, and according to the Museum of London, he built a communal ‘longhouse’, a communal privy which would have overhung the Walbrook river. He also ensured that the City was able to buy back the land that the King had confiscated.

Although he did own property, he did not own large estates, including a large estate outside of London, as would have been normal at the time for a person of his position and wealth.

He was Mayor of the City of London in 1397, 1406 and 1419, and he was also an MP, as well as being a member of the Mercers Company.

He wife Alice died in 1410, and Whittington died in 1423, and as they had no surviving children, much of Whittington’s wealth was left for charitable purposes.

The date on the plaque is 1423 for Richard Whittington’s house being on the site. This is the year that he died, and it highlights one of the problems with these plaques, in that they do not explain the relevance of the date.

Whilst it was the year he died, was he living in the house at the time, how long had he owned or lived in the house, why is 1423 important as regards the house?

But there is a much stranger date on the next plaque.

Richard Whittington Founded and was Buried in this Church 1422

The plaque can just be seen on the corner of the church, highlighted by the red arrow:

So, there is an immediate problem with this plaque, according to nearly all the sources I have read, Richard Whittington died in 1423, not 1422, so at the time of the date on this plaque, claiming burial in the church, he seems to have been very much alive.

I may be wrong that the date on the plaque refers to his year of death, it may be something to do with the church. According to records in the London Metropolitan Archives, Whittington paid for the rebuild of the church in 1409, so did it take thirteen years to complete, and was being reconsecrated / reopened in 1422?

This is one of the problems with some of the plaques in the City of London, they do not provide any context to some of the dates listed.

The sources stating his death was in March 1423 include:

Along with many others books and websites. An example of a book which could perhaps be expected to have the correct date is Old and New London by Walter Thornbury, where in a comprehensive listing of Lord Mayor’s of the City, Whittington is stated as having died in 1627, four years after what appears to have been his correct year of death.

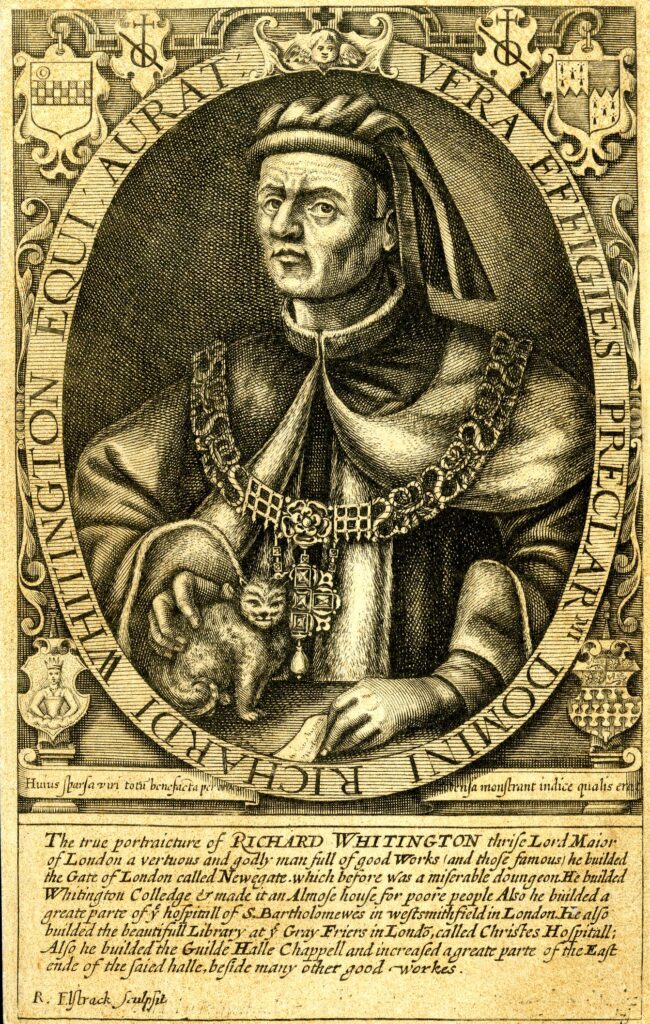

An early 17th century “true” portrait of Richard Whittington ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

Two hundred years after his death, the story of the cat seems to have been established as he is shown stroking a small cat in the above print, which also lists his good works:

“Thrice Mayor of London, a virtuous and godly man full of good works and those famous he builded the Gate of London called Newgate which before was a miserable dungeon. He builded Whittington College and made it an almshouse for poor people. Also he builded a great part of the hospital of St. Bartholomews in West Smithfield in London. He also builded the great Library at Grey Friers in London called Christes Hospital. Also he builded the Guilde Halle Chapel and increased a great part of the east side of the said hall, beside many other good works.”

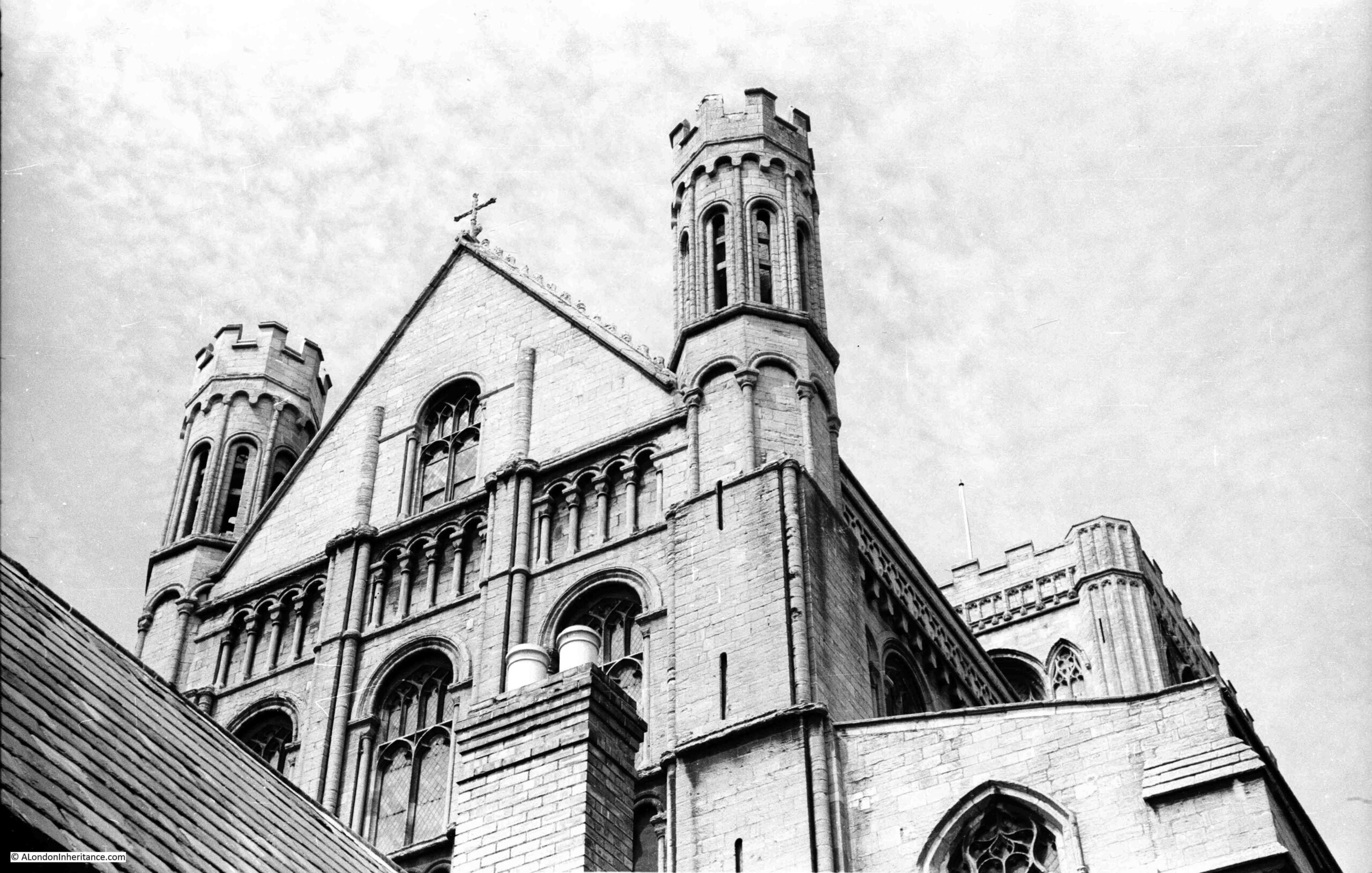

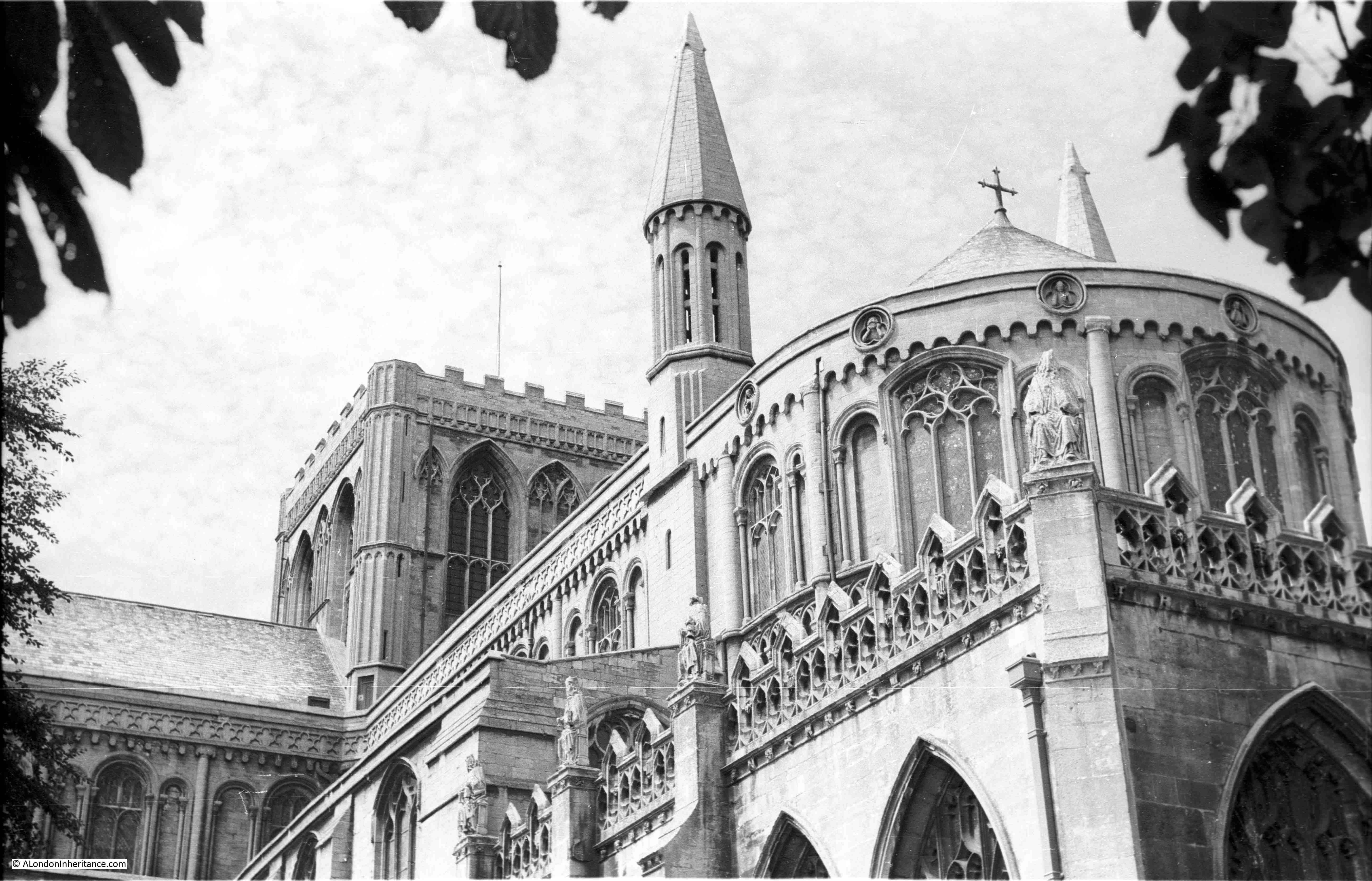

The plaque is on the corner of the church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal, and there are a number of stories regarding the founding and age of the church.

The plaque claims that the church was founded by Richard Whittington, but that is not quiet true.

The first reference to a church on the site dates from 1219. The name of the church comes from the sellers of paternosters or rosaries who were based in College Hill, which was then called Paternoster Lane. The Royal element of the name comes from a now lost nearby street called Le Ryole, which was a corruption of the name of a town in Bordeaux called La Reole. The street was apparently home to wine sellers, which presumably explains the Bordeaux connection.

Richard Whittington’s involvement with the church dates from 1409 when he paid for the rebuilding of the church, and the extension of the church by the purchase of a plot of land in the street Le Ryole.

Although he was not responsible for the founding of the original church, Whittington did found a College within the extended church for the training of priests, the College of St Spirit and St Mary. The association of the church with the college enabled St Michael’s to become a collegiate church, so perhaps this is what the plaque is referring to.

The college is also the reason why the street is called College Hill.

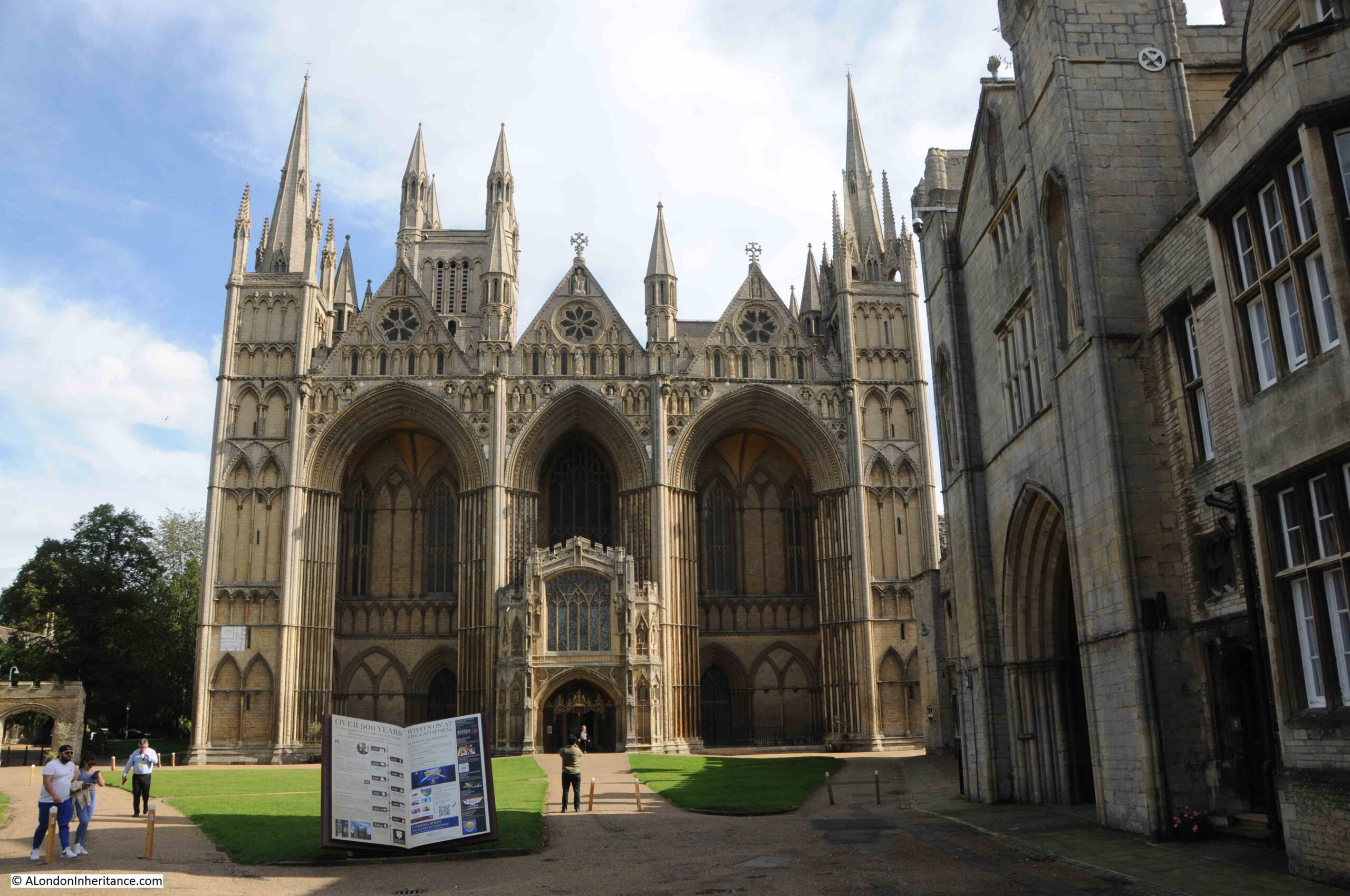

The church was destroyed in the 1666 Great Fire, and rebuilt by Wren, with Nicholas Hawksmoor adding the steeple between 1713 and 1717.

The church was badly damaged during the last war, and there was a proposal to demolish all of the church except for the tower, however this was opposed by the Corporation of the City of London, and the church was finally rebuilt and restored in the late 1960s, the last City church to be rebuilt after the damage of the early 1940s.

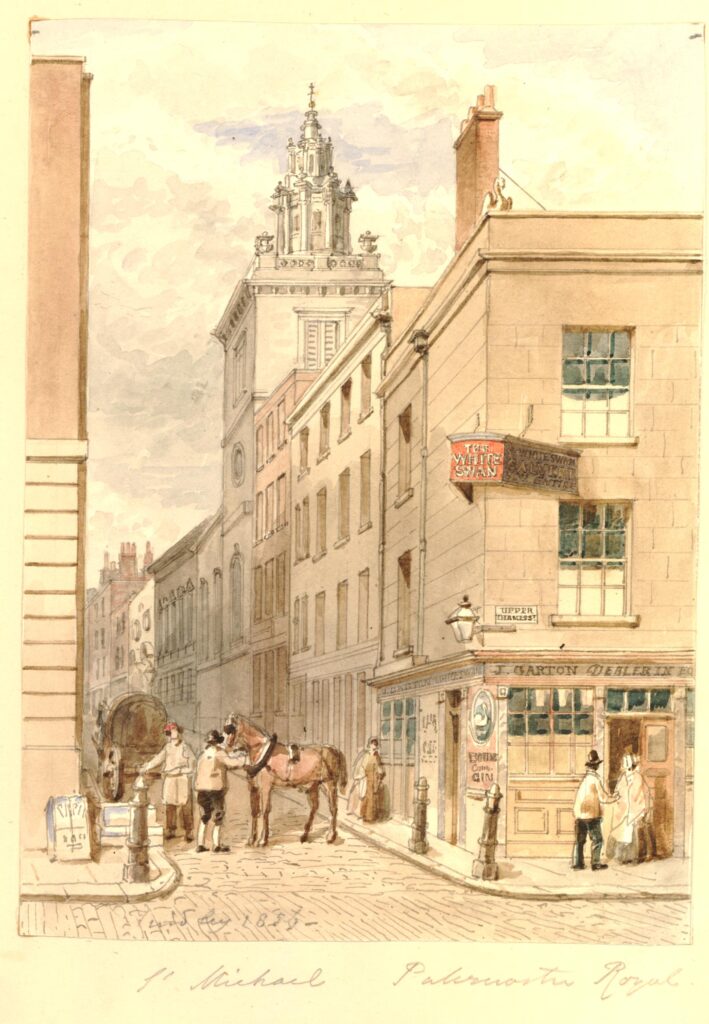

The tower and steeple of St. Michael Paternoster Royal:

St. Michael Paternoster Royal as it appeared in 1812 ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

And by 1859, houses and a pub appear to have been built on the open space to the south of the church, down to Upper Thames Street, with a pub, the White Swan on the corner ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The main door to the church:

Every time I have walked past the church, it has been closed. I hope at some point I will be able to get in and write a more comprehensive post on the church.

Although there is nothing left of Richard Whittington’s tomb, there is apparently a marked stone on the floor near the altar recording the location of his burial place.

The view looking up College Hill is shown in the following photo. The hill is an indication that the street is sloping down towards the Thames.

The following history of the street name is from one of the books on London that does seem accurate and well researched, Harben’s “A Dictionary of London” (1918):

“The earliest name Paternosterchurch Street (1232) commemorated the church, then in all probability its distinguishing feature.

The subsequent name ‘La Reole’ recalls the memory of the foreign merchants assembled there for purposes of their trade of whom a great number are said to have imported wine from the town of ‘La Reole’ near Bordeaux and to have named the street in which they resided after their native town. The name appears to have been given in the first instance to one principal messuage or tenement, and only later applied to the whole street.

The present name commemorates the great foundation of Whittington College in the church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal.”

There is one more plaque to find in College Hill, and this is on the left / west side of the street, so I walked back up the street to find the site of:

The Duke of Buckingham’s House

As you walk back up College Hill, on the left, on a large brick building, next to an entrance to a courtyard, is another plaque, arrowed in the following photo:

The plaque states that this is the site of the Duke of Buckingham’s House, 1672:

The information on this plaque does not really explain which Duke of Buckingham, and the relevance of the date. Was 1672 when the house was built, when it was demolished, or when the Duke of Buckingham lived in the house, and if it was only for a single year, why does it need a plaque?

Firstly, who was the Duke of Buckingham?

The Duke of Buckingham in the 17th century refers to two generations of the Villiers family.

George Villiers purchased a number of large estates in the early 17th century, He was a favourite of King James I, and one history of the county of Rutland (where Villiers primary country estate was located) states that “It was his elegant legs that first brought George Villiers to the adoring attention of James I”.

George Villiers was made the first Duke of Buckingham in 1623.

James I died in 1625 and Charles I then took the throne and George Villiers continued to have royal favour, although it appears he was not a popular man, and was often used as a scapegoat for poor decisions.

Villiers end came about due to failed naval battles. He had the position of Lord Admiral, and led a naval force to attempt the relief of La Rochelle. The attempt was a failure and there were around 5,000 casualties in the forces led by Villiers.

A second expedition also failed, and following these two naval disasters sailors and soldiers were left unpaid, fed up with Villiers command and willing to mutiny. In the naval town of Porrsmouth, sailors rioted even though Villiers promised to provide their pay from his own funds.

Such was the feeling among the sailors of the navy, that one of their number, John Felton assassinated Villiers on the 23rd of August 1628, and that was the end of the first Duke of Buckingham.

Seven months prior to his death, his first son George was born, and it was to this infant that the title of the second Duke of Buckingham passed.

George Villiers, the second Duke of Buckingham grew to follow in his father’s footsteps and continue to support the king, Charles I. He fought on the Royalist side during the Civil War and escaped to Europe with the future Charles II he was later captured and prisoned in Jersey, Windsor and the Tower of London.

After Cromwell’s death in 1658, Buckingham was released from the Tower in 1659, and with Charles II restored to the throne, Buckingham had his estates restored and became a rich man, and was also at the centre of the royal court.

Buckingham did though have very expensive and extravagent tastes, and also racked up large gambling debts.

George Villiers, the Second Duke of Buckingham died in 1687, and his estates were sold to pay off his debts.

He had no legitimate heir, so the 17th century father and son, both George Villiers and the first and second Dukes of Buckingham ended in 1687, so the plaque refers to one or both of these two men.

I have read in some well respected blogs that the house belonged to George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, with no mention of the second Duke. The first Duke died almost 50 years before the date on the plaque.

The book “A Handbook for London, Past and Present” by Peter Cunningham (1849) states that Buckingham House was “A spacious mansion on the east side of College Hill, for some time the city residence of the second, and last Duke of Buckingham“.

There is an error in this statement, as if the plaque is in the right position, Buckingham House was on the west side of College Hill, not the east.

The City of London Queen Street Conservation Area document states that “The Dukes of Buckingham owned a substantial property accessed from the west side of College Hill until its redevelopment in 1672”.

Strype, writing in 1720, stated “Buckingham house, so called as being bought by the late Duke of Buckingham and where he some time resided upon a particular humour: It is a very large and graceful Building, late the Seat of Sir John Lethulier an eminent Merchant; some time Sheriff and Alderman of London, deceased“.

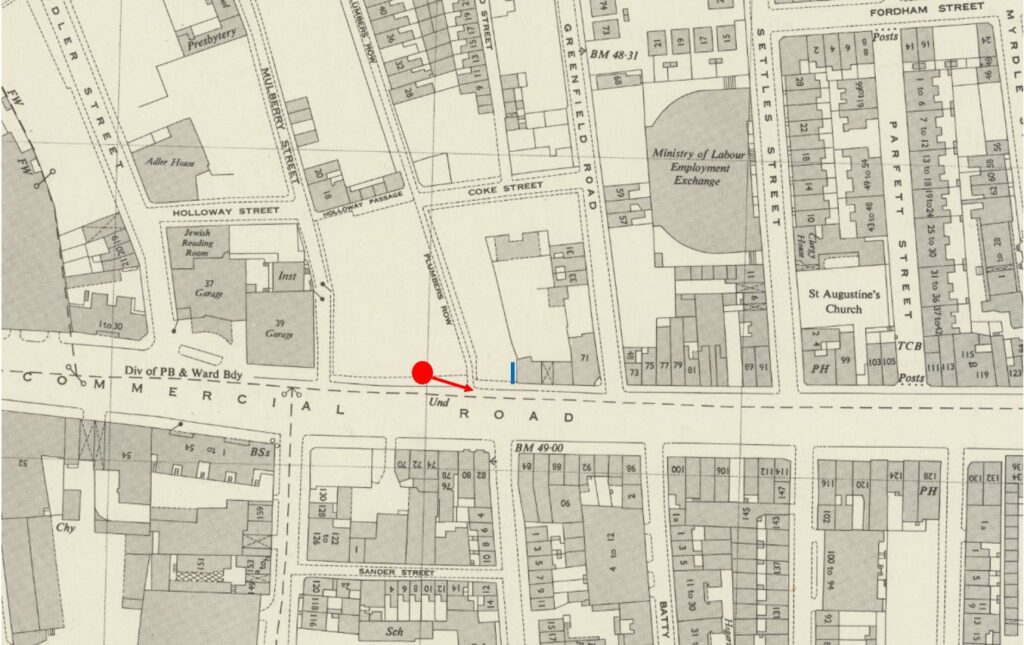

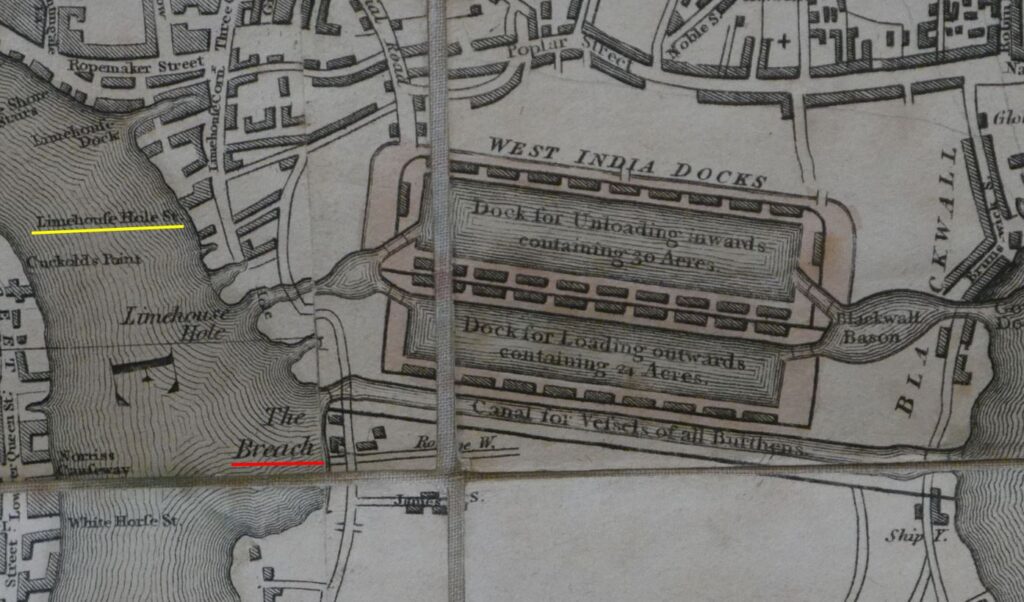

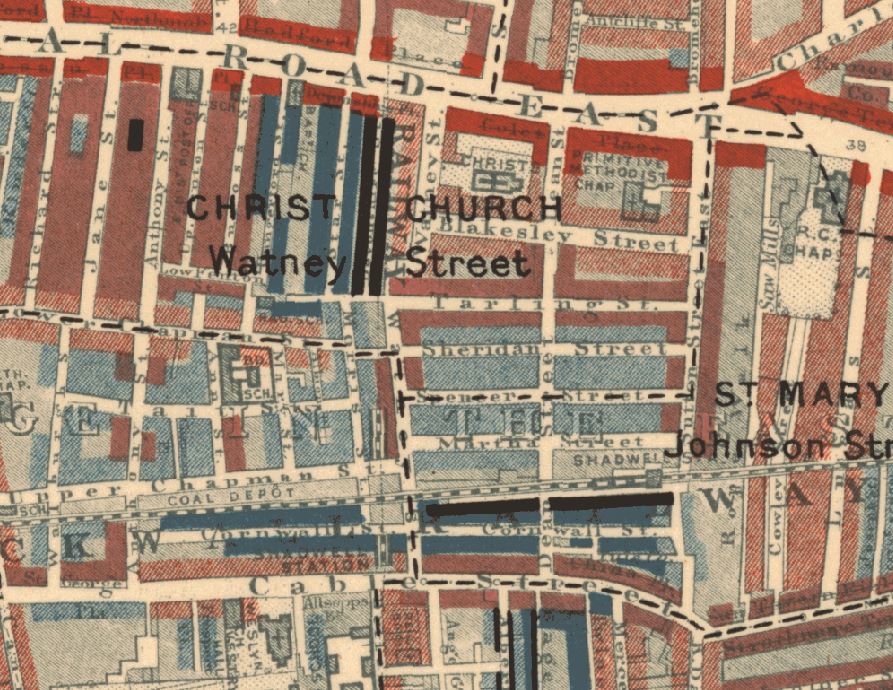

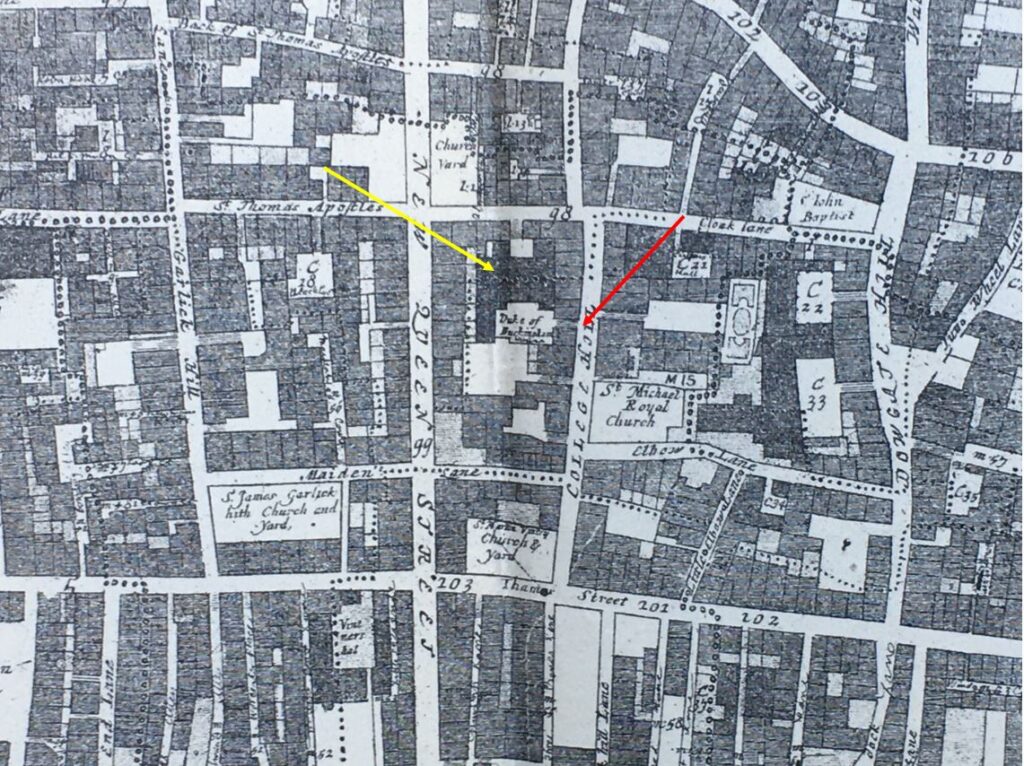

Buckingham House was shown on Ogilby and Morgan’s 1676 map of London. The yellow arrow in the following extract points to the house which was a substantial building for the area, between College Hill and New Queen Street:

The building appears to have been accessed through an alleyway from College Hill which the red arrow points to, and as far as I can tell by aligning maps, an alley still exists in the same place today (the Buckingham House plaque is on the left of the entrance to the alley):

At the end of the alley is the small space of Newcastle Court, surrounded by offices, but occupying a small part of the space that was once in front of Buckingham House.

So after reading many different sources, there is still no final answer as to which Duke of Buckingham owned Buckingham House, or whether it was both of them. And no firm answer as to the relevance of the date 1672.

In writing these posts, I try and avoid stating what may appear to be simple statements of truth, when in reality there are many different versions, and I suspect it would only be after some considerable effort in various archives, that the correct story could be revealed, if documents covering the period, the two Dukes of Buckingham, and the house on College Hill still remain.